To be humble is to walk in truth. Saint Thérèse.

On The Virtue Of Humility

In his famous essay The Ethics of Belief, the English mathematician and philosopher William K. Clifford (1877) proposes the following postulate:

...it is wrong always, everywhere and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence.

Leaving aside the evidentialist cut (and the severity) of this postulate, I want to direct attention to the epistemic duty - the duty of truth - it presupposes we ought to seek for the truth and avoid falsehood or, in other words, human beings, as epistemic agents (producing and transmitting agents of knowledge) must seek knowledge and avoid ignorance.

The relevance of such duty in a work on humility lies on the fact that the conception of humility that I will present is one according to which being humble is part of selfknowledge, and just as in the general field of knowledge we must seek the truth and avoid falsehood, we must do the same in the field of self-knowledge. This vindicates the place of humility as a virtue, that is, as a golden mean between a deficiency and an excess and admits its compatibility with the processes of growth and selfimprovement.

Before beginning our exploration, it is convenient to make some notes to help us prevent verbal misunderstandings. The first is to stipulate that, for the purposes of this work, the words “modesty” and “humility” refer to the same disposition or character trait that is the object of this meditation. The second is to indicate that when speaking of “humility” I will not do so in the contemporary sense that seems to be heir to the contrast in Roman society (Snyder, 2020, 11) between the humiliores (people of low status) and the honestiores (people of high status and lineage); a sense present in expressions such as “she is a humble woman, coming from a village”.

A fruitful way to begin exploring what humility is, why it is a virtue, and why it is commendable, is by reviewing three great perspectives on what it means to “be humble” from the Christian vision (Dunnington, 2015):

Perspective of divine creation: human work and achievements are insignificant compared to the magnificence and splendor of God’s work. Therefore, any inclination to feel pride over our achievements or work is, quite frankly, laughable (Richards, 1988, 255; 1992a, 1)

Perspective of sin: There is nothing good in human nature. We are tainted by original sin to the point that there is nothing magnificent or worthwhile in what we do. Therefore, there is no reason to be proud of what we do or achieve (Richards, 1988, 253; 1992a, 7).

Perspective of Grace: everything we do that is good or valuable we owe to God and his Divine Grace. It is He who deserves all the credit for our work. Therefore, any pretense of pride is nothing more than an incorrect attribution of the credit that is due to God. (Richards, 1992b, 578)

In an equivalent way, from a secular point of view, the following versions of the same perspectives can be formulated:

Perspective of the cosmic scale: Life and human work are tiny and irrelevant compared to the grand scale of the cosmos. Our achievements are microscopic on that scale. No matter how great our successes seem, how remarkable our actions seem, the reality is that there is nothing especially consequential about what we do. The sensible thing is not to let ourselves be carried away by the temptation of giving ourselves more importance than we really have and to admit that every work, anguish, ambition, or human conquest is nothing within the framework of the immensity of the cosmos.

Perspective of human imperfection and limitation: Human beings are fallible beings, full of flaws and errors. There is little or nothing extraordinary about us, which is why it is not reasonable to take ourselves too seriously, much less brag about our work and our achievements.

Perspective of chance and the help of others: Forces and agencies other than our own are often involved in our achievements and the development of our qualities or talents. It is important to recognize the help we receive from other people (i.e., mentors, coaches, parents, friends, partners, etc.), as well as to recognize that there are social and historical circumstances that not only escape our free will but rather condition it. To these circumstances is due to a significant extent, we must admit, what we are and what we do. People do not choose where they are born, who their parents are, their social status and, in general, they do not choose the circumstances in which their life emerges and flourishes. Consequently, it is important to admit that much of the credit for our conquests and talents corresponds to those who help us or, even, are substantially a product of the circumstances that frame (that is, condition) our free action, or more specifically, our agency

The virtue of humility plays a central role in our lives. It is not surprising that there are those who find that petulant, vain, and proud people are people with whom it is more difficult to build meaningful relationships since they consider - not without reason - that the self-centeredness and sense of superiority characteristic of those attitudes are, not only unjustified and morally reprehensible, but also makes it difficult to interact with them. Being with entitled and proud people means living with people who “either talk or explode”, putting up with derogatory expressions about our interests and ideas (or those of third parties), getting used to not being able to finish sentences and questions and, in general, involves interacting with people who do not treat others to the same standards with which they treat (and expect to be treated) themselves. The lack of humility, it can be said, is both morally reprehensible and costly in terms of social coexistence between individuals.

This suggests that humility is a desirable trait. However, while these ideas subsist, there is a rather well-spread conception of humility that runs counter to that desirability. I will call it a folk conception for the purposes of this exposition and in essence it points out that humility is a sort of recurring, though slight, mistake in self-knowledge. That is, humility is a virtue that implies ignorance since its manifestation “is dependent upon the epistemic defect of not knowing one's own worth” (Driver 2001, 16-17).

The perplexity that this conception throws lies in the following: why should we value a recurring error positively? If we think about people whom we admire for, for example, their great intelligence or wisdom and, despite it, their humility, how could it be expected that these admirably intelligent or wise people - if they are to be considered humble - should be the only who do not realize that they possess that intelligence or wisdom, or be the ones who fail to evaluate it accurately, by systematically making mistakes when thinking about it? Furthermore, how, and why should this ignorance be cultivated? And even more into the core of the perplexity: why should it be considered a virtue at all any form of systematic shortcoming or failure in seeking truth and avoiding falsehood, whether on the field of self-knowledge or the field of knowledge in general? How would humility justifiably defeat or pose a limit to the fullfiment of this fundamental epistemic duty?

Consider a case like that of J.R.R. Tolkien, a philologist of recognized authority for his outstanding knowledge of the Anglo-Saxon. Does Tolkien’s being humble mean that everyone except him would be able to recognize his credit and authority for procuring such knowledge since Tolkien himself would be doomed to systematically err in making that self-assessment?

In Canto II of Inferno, we observe in the Comedy that Dante, after an examination of conscience, bursts out and asks Virgil: Bard! Thou who art my guide, consider well if virtue be in me sufficient, ere to this high enterprise (…)

Not Aeneas I am, nor Paul. Myself I deem not worthy, and none else will deem me. I, if on this voyage then I venture, fear it will in folly end. Thou who art wise better my meaning know'st than I can speak. (Alighieri, 1959, p. 10)

This attitude of Dante, hesitant and overwhelmed, fits well with the folk conception of humility, especially since, as observed later in the song, Virgil explains the appearance of Beatriz in Limbo and reproaches him:

What is this comes o’er thee then? Why, why dost thou hang back? Why in thy breast harbour vile fear? Why hast not courage there, and noble daring; since three maids, so blest, thy safety plan, e'enin the court of heaven. (Alighieri, 1959, p. 13)

We then have a Dante-character who underestimates himself, who does not know himself worthy of the path set before him, while Virgil, Beatriz and the other holy women know him worthy.

In contrast to this Dante-character who doubts himself, we have in Canto IV a Dante who meets Homer, Horace, Ovid and Lucanus in Limbo, the First Circle of Hell, place of virtuous souls who were not baptized. They, together with Virgil, are the “great spirits”, the greatest poets of antiquity. This is how we are told:

…when I kenn'd a flame, that o’er the darken’d hemisphere prevailing shined. Yet we a little space were distant, not so far but I in part discover'd that a tribe in honour high that place possess'd.

(…)

«Honour the bard sublime! His shade returns, that left us late! » No sooner ceased the sound, than I beheld.

(…)

«When thus my master kind began: “Mark him, who in his right-hand bears that falchion keen, the other three preceding, as their lord. This is that Homer, of all bards supreme; Flaccus the next, in satire's vein excelling; the third is Naso; Lucan is the last.” (…)

«So, I beheld united the bright school, of him the monarch of sublimest song, that o'er the others like an eagle soars.

When they together short discourse had held, they turn'd to me, with salutation kind beckoning me; at the which my master smiled. Nor was this all; but greater honour still they gave me, for they made me of their tribe; and I was sixth amid so learn'd a band. » (Alighieri, 1959, pp. 25-26)

From the point of view of the folk conception of humility, the immodesty not of the Dante-character but of historical Dante to see or place himself at the level of Homer, Virgil and company is incompatible with the attitude of someone truly humble. But can we honestly qualify as petulance Dante’s conviction about the significance of his work? Not a few will say that in truth Dante’s place is, if not above, then at least on a par with that of Homer, Virgil, and the others. History has shown that without a doubt, Dante is great among the greats. That he was clearly aware of the transcendence of his work does not seem foolish or arrogant. In truth, whoever affirms that Dante is the “poet of poets” may not be much wrong if she is wrong at all. Why should we all be capable of verifying the magnum art of the Florentine in its fair measure and, nevertheless, judge him arrogant since he himself (with the limits of his location in space and time) had a clear intuition of how great it was?

Similarly, in The Lord of the Rings we find an Aragorn who is hesitant from chapter 5 of the book two to chapter 1 of the book three, that is, between the events of the Bridge of Khazad-Dûm and the crisis that occurred between the Amon Hen and Parth Galen. With the loss of Gandalf, Aragorn begins to waver about his ability to lead the Company, and the upheavals that shake his spirits reach a climax with the death of Boromir, the capture of the halflings, the disappearance of Frodo and Sam, and, without further ado, the irrevocable dissolution of the fellowship. In those moments we observed how the dúnedain and great captain bitterly lamented: “It is I that have failed”, “All that I have done today has gone amiss. What is to be done now?”

Despite this or, rather, precisely because of the unfortunate adversities that the heroes face in those moments, both the reader and the characters themselves maintain their confidence in Aragorn’s abilities as a leader. Gimli and Legolas provide insight to Aragorn’s deliberations with their views, but ultimately it is clear that the decision rests with the ranger.

From the perspective of the folk conception, Aragorn’s humility -we would say- lies in the fact that despite being the most apt to judge the situation and decide the path to follow, he himself does not have enough confidence, he does not consider himself so apt. But with this we condemn the one whose judgment we consider the most correct and reliable to be the only one among the heroes to err when it comes to judging his own ability, while - paradoxically - it was Aragorn’s sound judgement what ultimately brought a satisfactory solution to the crisis. He correctly (and humbly) acknowledged that the Ring Bearer was beyond his reach and that it was no longer his duty to protect him. Thus, he rightly chose to help those who might still have a chance of greatly benefiting from his help (i.e., Meriadoc and Peregrin).

In the Aristotelian tradition, a virtue is a golden mean medium between a defect and an excess. An easy way to exemplify this is with the virtue of courage:

Cowardice < Courage <Rashness

We say that a person who lacks courage is a coward. Equivalently, we say that a person who is “too brave” (excuse the colloquialism) is a rash or reckless person. The virtue of courage is the happy medium or golden mean between the defect of cowardice (the lack of courage or bravery) and rashness (the excess of courage or bravery).

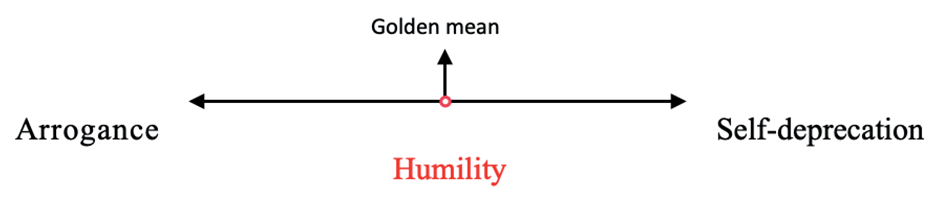

Correspondingly, humility understood as a golden mean must be located between a defect and an excess. Let us call - subject to the fact that better denominations can be proposed - arrogance to the deficiency, to the lack of humility; and let us call self-deprecation to the excess.

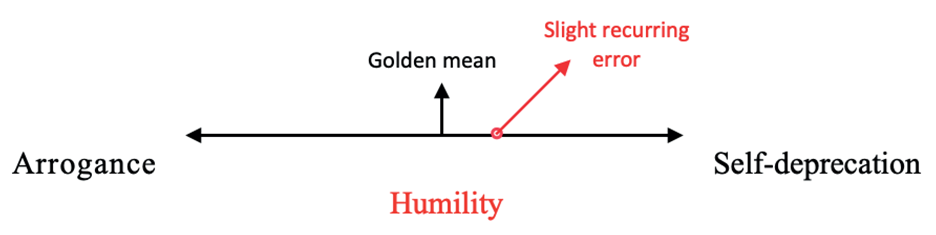

In fairness, it must be clear that the folk conception of humility does not suggest that the humble places herself at the extreme of excess, but that her recurring error is a slight error. That is, within the scale that goes from arrogance to self-deprecation, the humble one is located not in the center, but in a place slightly on the side of self-deprecation, but still far from it. Visually, the idea would be as follows:

If this second conception is admitted, in addition to the perplexities already noted, we may ask: Why should the slight error be acceptable only when it occurs towards excess? What about the cases where the self-knowledge error falls on the defect’s side of the spectrum? If humility consists of a slight recurring error that manifests itself as a slight underestimation of oneself, one’s work and talents, wouldn’t systematically being a little arrogant also count as humility? The folk conception thus faces the challenge of explaining why the slight overshoot is permissible and the slight undershoot is not.

The correct strategy, it seems to me, is to abandon the folk conception. However, one must recognize a powerful intuition about what humility is that underlies both the perspectives of the cosmic scale (of divine creation), human imperfection (of sin) and the chance and help of others (of the Gift of Grace), as well as the folk conception itself, namely: being humble is typically understood and manifested as an act of non-overestimation.

The problem with the folk conception, in my opinion, is that it places so much emphasis on preventing overestimation of one’s own work, talent, or conquest, that it seems to forget that a conceptual part of humility, as a midpoint, is also not underestimating it. The virtue of humility is, therefore, a virtue of precision, it is the ability to judge one’s own work, talent, or conquest in its proper dimension. The virtue of humility is a trait of people’s character - indeed, an intellectual habit - that enables them to know themselves accurately and fulfill the more general epistemic duty of seeking truth and avoiding falsehood, within what is reasonably expectable for human agents.

In this way, humility allows people to know their limits and capabilities sufficiently to identify their strengths and weaknesses. In this sense, humility is a sine qua non condition for self-improvement. She who does not know herself cannot properly endeavor into becoming a better person. It is not an achievable goal for someone who has lost hope, that is, someone who self-deprecates. And, correlatively, it may not seem necessary to the eyes of someone who has too high an opinion of herself, that is, the arrogant.

Regarding the latter, it is relevant to recall a passage from Plato in The Symposium (204a):

Neither do the ignorant ensue wisdom nor desire to be made wise: in this very point is ignorance distressing when a person who is not comely or worthy or intelligent is satisfied with himself. The man who does not feel himself defective has no desire for that whereof he feels no defect. (Plato, 1925, p. 204a)

The absence of humility is, then, a form of ignorance. Only that, since oneself is the object of knowledge of humility, its deficiency is a lack of self-knowledge. It is a kind of myopia that we human beings suffer when we observe ourselves, obtaining not the truth, but a distorted image.

To combat this ignorance and seek full self-knowledge, the humble person will be someone who maintains a correct sense of herself, the value of her talents, the importance of her acts and works, resisting the banal temptation of praise, fame and flattery; keenly acknowledging the role that other people, other wills and even fortune have played in the development of her person, with all her weaknesses and strengths. Humble are the people that, without losing orientation regarding their place in the world, do not underestimate their value, nor overestimate it, maintaining equidistance between the vices of arrogance and self-deprecation and always preserving a clear sense of their limits and their capabilities, always open to discover and accept the truths -often less than flattering- about their condition as human beings.

Bearing in mind this conception of humility as a golden mean, I will now proceed to sketch a general outline of the grand scheme underlying John Ronald Reuel Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings from which we can identify a singular message: that humility triumphs over arrogance.

About Sauron And The Myopia Of The Great Eye. Or, About Gandalf And The Garments Of Humility

Gorthaur, Annatar, The Necromancer, The Enemy, Dark Lord, Lord of Mordor, Black Master, Lord of Barad-dûr, the Lidless Eye or the Great Eye; These and more were the names that through centuries different people in different corners of Arda gave to Sauron, The Lord of the Rings. Reflecting on his story, from his origin to his disgraceful end, is reflecting on a story about temptation, the resilience of vice and perdition in the deepest abysses of pride and ambition.

Sauron, of course, was not of flesh and blood. Even saying that he was immortal demands some clarification, since life and death are facts of nature and Sauron comes from a realm that precedes nature and, therefore, the concepts of mortality and immortality do not apply to him, at least if they contain some biological dimension or aspect. Sauron does not belong to the realm of biology.

Sauron was, of course, one of the Ainur. He was an offspring of God’s thought that existed with Him before time, before space, before aught else was made. Furthermore, he joined his voice to those of his brothers and sisters (the rest of the Ainur) and performed a great Music before God, who first turned it into a vision and, later, inflamed it with the Secret Fire and said: “Eä! Let these things be”. Thus, was born the World that Is.

Ilúvatar offered the Ainur who wished so, the possibility of entering that world to start the works of ordering that primal cosmos and prepare it for the awakening of the Children of Ilúvatar. And many spirits, Sauron among them, did so. Once inside Eä, they were ordered into two large groups. The greater spirits were the Valar, the Powers of the World. His assistants and companions, lesser spirits, were the Maiar. Sauron belonged to this second order and, in addition, was part of the people of Aulë, the Vala blacksmith, the great engineer of Eä. From him, he would undoubtedly acquire the gifts that thousands and thousands of years later he would use to become a maker of rings and a builder of towers.

It has been said that from the beginning Sauron’s virtue was his love of order and coordination (Tolkien, 1993, p.396) and, for this very reason, he participated at first in the harmony of the Ainur and not in the discord of Melkor. Sauron’s fall into the corruption of Melkor does not occur, then, at its origin, but took place later at some unspecified moment in the development of Eä’s history. And it happened because of a temptation that he could not resist: given his proclivity towards order and coordination, at some point, he saw Melkor and contemplated with maximum admiration his power and effectiveness to impose his will on the world and other beings. And so, what originally was Sauron’s virtue, silently and gradually turned into vice and, ultimately, into betrayal. He left the people of Aulë and became Melkor’s lieutenant, the first among his captains. And Melkor’s bonds were strong, and Sauron soon grew in pride and vanity under his rule.

Of course, as Tolkien himself indicates in his Notes on the Motives for The Silmarillion included by Christopher Tolkien in The Ring of Morgoth, the ambition awakened by Melkor in Sauron was never to such a degree as to make him fall into the absurdities of the former.

Melkor’s rebellion against God can, of course, be understood as a lack of humility. Melkor desired to be like God, to make things of his own device and, for such purposes, obtain the Secret Fire or Imperishable Flame. He looked for that flame in the Void, before Eä, but he would never find it for it was with Ilúvatar.

Melkor’s arrogance is sentenced by God at the end of the Music when he spoke:

Mighty are the Ainur, and mightiest among them is Melkor; but that he may know, and all the Ainur, that I am Ilúvatar, those things that ye have sung, I will show them forth, that ye may see what ye have done. And thou, Melkor, shalt see that no theme may be played that hath not its uttermost source in me, nor can any alter the music in my despite. For he that attempteth this shall prove but mine instrument in the devising of things more wonderful, which he himself hath not imagined

Despite this sentence, when Melkor saw The Music turned into a vision, he was captivated like the rest of his brothers and sisters by the beauty of that world which grew and developed and, like many of them, he also entered Eä. But his attitude did not change, and he continued to act with pride, involving himself in everything that the other spirits did, twisting things to fit his own designs and desires and claiming for himself the works of others and the young Earth, yet Manwë opposed him and said: “(t)his kingdom thou shalt not take for thine own, wrongfully, for many others have laboured here no less than thou.” And so, since the dawn of time, the cosmic conflict between good and evil in Eä was formed, the struggle between Melkor and the Powers of Arda.

And when Melkor could not take things, he began to invest his forces in destroying them. And when he saw that he couldn’t destroy them, he began to just ruin them. But he inevitably found that, as Ilúvatar had decreed, he could not alter The Music in his despite. So that when he tried with his flames to destroy the waters, new vapors took place from which clouds and rains were born, and new melodies and harmonies were woven between Manwë and Ulmo. Again, as Ilúvatar sentenced, Melkor soon bitterly realized that no matter how hard he tried, he could not but be an instrument for the creation of things more wonderful that he himself had not imagined, for Ilúvatar also said:

Behold your music! This is your minstrelsy and each of you shall find contained herein, amid the design that I set before you, all those things that it may seem that he himself devised or added. And thou, Melkor, wilt discover all the secret thoughts of thy own mind, and wilt perceive that they are but a part of the whole and tributary of its glory

But Melkor’s pride was too great, and he could not accept his insignificance compared to that of the Alpha and the Omega and soon degraded himself, the most powerful inhabitant of Eä, to the point of having been reduced by the end of the first age to the existence of a genuinely incarnated being, fearful of his body, obsessed with subduing everything, destroying everything, depriving it of its beauty, marring it, denying it. But even if he had emerged victorious and had been able to reduce all of Eä to a shapeless mass, in it he would find his inevitable and eternal defeat, since the shapeless mass itself would have an existence independent of him, despite him. That was the nihilism of the purposes of Melkor, of Morgoth, the dark enemy of the world. An absurdity that had its origin in a lack of humility, at the most obvious and fundamental level: the irresistible humility that is born from the most elementary understanding and contemplation of the glory and magnificence of God’s work.

For his part, Sauron never fell for that absurdity. He never embarked on the business of destroying so much as on dominating. It was, as already stated, his appetite for order and coordination that betrayed him, being seduced by Melkor’s relentless and vast power and his ability to exert his will even at the cost of himself.

When the dark enemy of the world was defeated in the War of Wrath, Sauron appeared before Eönwë, the great captain of the hosts of Valinor. And we are told in the Quenta Silmarillion that he was remorseful or faked it very well. And Eönwë exhorted him to submit to the judgment of the Valar, but Sauron’s pride was great for he had achieved much dignity under Morgoth and he had not the humility to bow before The Powers and acquiesce to a potential sentence of servitude.

Thus, the vain Sauron preferred to flee humiliation and hide in the east. And not long afterward he reemerged in lucid colors, undertaking new plans to seize the domain of Elves and Men, eventually rising as a new Dark Lord, and establishing Mordor, the land of shadow, as his stronghold.

Sauron by this time was already a haughty and arrogant individual who viewed the Children of Ilúvatar with contempt, as his inferiors, considering that the best thing that could be done was to submit them to his domain, to his notion of order, to his vision for Middle-earth. He then hatched an evil plan to subdue the Elves, whom he hated the most and in whom he recognized the greatest power. He tempted them by presenting himself as a beautiful figure and offering gifts to make the continent as beautiful a place as the home of the Valar. And it was in Eregion that the ears of the goldsmiths of the Feänorean school heeded his words, and it was there that the Rings were forged.

In Mordor, Sauron secretly forged his Ring and his betrayal was revealed: one Ring to rule them all. Not a ring to destroy them, like Melkor. Nor a ring to deprive the world of its beauty or instill its evil in it, but a ring to subdue them all, to find them, to attract them and in the darkness, bind them. This was the terrible will of domination of the Lord of the land of shadow.

As Melkor debased himself by infusing and marring the world with his evil spirit, Sauron was foolish enough to invest his power in that Ring. And, in truth, the ties with which Melkor subjected him had to be deep, so that Sauron would fall into the indignity of embezzling the high and inherent purity of his being, offspring of the thought of God, in such vulgar a thing as a ring forged with minerals from the earth. Because we are dust, but Sauron was not dust. Sauron was something else, something nobler and more beautiful. But he had lost to such a degree the sense of his own being, that, moved by the dishonest appetite to dominate others (which he illegitimately and arrogantly considered himself entitled to), he tied his fate to that of the Ring.

It was in this way that the one who loftily called himself the Great Eye inadvertently and progressively perfected the conditions for his great debacle. His bitterness and pride grew over the years and eventually distorted his gaze and he became unable to comprehend the virtues of those who opposed him.

Of course, although it can be said that Sauron was more intelligent than Melkor by never falling into the absurdity of wanton destruction, the truth is that he did not come to represent a threat of the magnitude of that of the first Dark Lord. The defilement of Arda is an inescapable fact in this version of The Music and in a limited and partial way it means that Melkor got away with it, to some extent. In fact, he ruined the Gifts of Ilúvatar for his Children.

Melkor’s corruption made Middle-earth a sad and gray place for the firstborn. The gift of immortality then became a burden to them. For their part, the second children did not receive the gift of death with hope, but with fear. “The bitter Gift of Freedom” as it came to be called.

Sauron did not represent a cosmic threat capable of scoring “triumphs” of this magnitude, but he was heir to the corruption brought about by Melkor and with macabre cunning he wove the most terrible plans to exploit it to the fullest, bringing with it important evils to the world. Over the course of the Second Age, through the forging of the Rings of Power, he became the mastermind behind the second fall of the Elves. And, during the twilight of that same period, he was the great promoter of the Ruin of Númenor, the second fall of Men.

These two events are, without a doubt, his greatest victories. But in both, he paid a high personal price to obtain them, and in neither case did he really get a chance to “taste the honey” of his crooked machinations. It must be stressed that his arrogance (based on a distorted sense of superiority) is the common denominator of the risks he took and the prices he paid in both cases: investing a large part of his personal power in the One Ring, tying his destiny to it, for the first; go as a slave to Númenor in the latter, convinced of his ability to deceive the Númenóreans and losing the ability to take beautiful physical forms in the resultant destruction.

In response to the threat posed by Sauron, the Valar intervened no longer with a War and a host. All such interventions held against Melkor scarred Arda in irreparable ways. Additionally, the Second Sons, humans - who could be a bit more fragile than Elves, especially in the absence of the possibility of reincarnation or serial longevity - were more centrally involved in this news conflict.

In the same way, to the Children of Ilúvatar corresponds a fundamental dignity based on which they are morally located in a certain degree of horizontality with the Ainur. They are called precisely “Sons of Ilúvatar” because none of the Ainur introduced them to The Music, but their themes were integrated by God himself. The falsity of the right claimed by Sauron to govern them lies in the non-recognition of that fundamental dignity shared with them. And the Valar, for their part, respecting such dignity, must maintain a consistent policy of not intervening except in exceptional circumstances. The Children should be the ones who, motu proprio, would fight the threat posed to the world by Sauron. That is, the free people should be the one who, freely adhering to the exercise of good, must triumph over evil.

It is not respectful of the dignity of the Children that, every time there is a problem or threat, the Valar design and carry out the solution. It is important to allow the Children to mature, learn and freely choose between good and evil. And it is under this approach that, in view of the events of the Second Age of the Sun, the Valar elaborated a more discreet, less robust strategy of intervention that consisted of sending emissaries to Middle-earth to advice or guide, not to govern, the people who remained free from the shadows of Mordor.

These emissaries were the wise men who made up the Order of the Istari. But the garments with which they appeared before the free people were those of humility since they were not sent as captains of great armies, dressed in resplendent armor, and carrying glorious banners. The Valar did not send generals or rulers. They sent counselors dressed in the humble regalia of wise old men. They were Maiar, spirits belonging to the high order of the Ainur, but inhabiting real elderly human bodies, not feigned as was typical of the physical manifestations in Eä of the Ainur and, consequently, limited in power and majesty. They were offspring of the thought of Ilúvatar genuinely embodied in human bodies, subject to their pains, their limitations, and the possibility of death (Tolkien, 1980, p.389).

They were entrusted with the far from simple mission of ensuring that the free people, from their freedom, resist the shadow of Sauron, preventing them from making great finery of the power and majesty that was inherent to them and restricting their work to discreet tasks of advice, guidance, and counseling, and not tasks of government and military command.

Gandalf, as we know, is the one who proved to be the greatest of those spirits that came from the West to the shores of Middle-earth. It has also been said that he was the most modest among them, both in personal appearance and because of the apparent smallness of his work, which consisted of pilgrimage among the towns, learning from their people and knowing the weaknesses and strengths of their hearts, rather than in the accumulation of science and the procurement of fortresses and relics. But his greatness was quickly perceived by Cirdan, the wise old guardian of the Gray Havens, who soon gave him Narya, the Ring of Fire (one of the three Rings of Celebrimbor) to help him consolidate hope in the minds of the people that he would meet during his transit through a world devastated by despair.

It is said that, just like Cirdan, only a handful of individuals (such as Galadriel or Elrond) could have reached a more or less substantive idea about who these elders were, but the emissaries themselves could not openly reveal it as that would be acting in the wrong way, contrary to the deep meaning of the mission explained lines above. But it is not entirely apparent what degree of understanding Sauron came to acquire about them.

Assuming Sauron figured it all out by catching Saruman when he used the Palantir of Orthanc, it’s notable that the Lord of Mordor would then have let a worrying amount of time go by without detecting or sizing up a serious threat. To be precise, Saruman ventured to use the Palantir until the year 3000 of the Third Age (one year before Bilbo’s birthday), by which time the Istari would already have been operating on Middle-earth for a significant number of centuries (something like twenty in the case of Gandalf, which would be the least of the cases as far as seniority in the performance of the mission is concerned).

Sauron’s actions in the years after Saruman’s subjugation and before the start of the War of the Ring did not show indications that he was particularly concerned about anything. If we consider that it is Gandalf, one of these Istari, who ultimately engineers his defeat to a large extent, it seems that either Sauron did not fully understand the wisdom of the Valar, or he underestimated his enemies, moved by an excess of confidence. A kind of short-sightedness to which a humble person would not be so easily subject, with a keen awareness of her limitations.

It was just the myopic pride with which Sauron underestimated his rivals that prevented the Great Eye from perceiving the plans for his overthrow. Gandalf fostered in Elrond the wisdom to trust the halflings, the beings apparently least fit to face the Enemy. This he stated at the Council of Elrond, regarding the strategy of using Sauron’s pride against him:

Well, let folly be our cloak, a veil before the eyes of the Enemy! For he is very wise and weighs all things to a nicety in the scales of his malice. But the only measure that he knows is desire, desire for power; and so, he judges all hearts. Into his heart, the thought will not enter that any will refuse it, that having the Ring we may seek to destroy it. If seek this, we shall put him out of reckoning

Greater would be the confusion of the conjectures of the Enemy when placing the hope of the world on the shoulders of the gentlest creatures: the hobbits. These individuals, especially Frodo, were fully aware of their lack of qualifications for such a mission. Frodo lacked any kind of training that we would consider relevant to the task. But having an exemplar clarity and awareness of the circumstances raised, without ever losing the sense of his place in the world and fully understanding the importance of his role in history, he obsequiously and freely assumes responsibility and bears the burden of Ring. In this regard, Elrond says:

I think that this task is appointed for you, Frodo; and that if you do not find a way, no one will. This is the hour of the Shire-folk, when they arise from their quiet fields to shake the towers and counsels of the Great. Who of all the Wise could have foreseen it? Or, if they are wise, why should they expect to know it, until the hour has struck?

But it is a heavy burden. So heavy that none could lay it on another. I do not lay it on you. But if you take it freely, I will say that your choice is right; and though all the mighty Elffriends of old, Hador, and Húrin, and Túrin, and Beren himself were assembled together, your seat should be among them

The rest of the story takes place in the way we all know and, finally, Gandalf -knowing the arts of humility and the disadvantages of its lack- proved to be right. Sauron never understood the webs that his rivals spun to deal him the fatal blow. Or at least he didn’t understand until the final moment when it was too late. Thus was forever dispelled the shadow that spread from Mordor over the world.

Under the proposed optics and under an understanding of The Lord of the Rings in its indissoluble unity with the myths of The Silmarillion, we can therefore appreciate a story about how humility triumphs over arrogance or, more generally (if preferred), a tale of virtue rising glorious and victorious over vice