1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic that started at the end of 2019 has had a significant impact on the history of the world, with relevant effects on human and economic losses as well as on employment. The consequences stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic required a societal reaction that directly affected both families and enterprises (Mucharraz y Cano et al., 2023). Its consequences will persist in the long term, and to mitigate potential risks, it is necessary to understand its effects on different groups with inequality problems, such as female talent, which also plays a key role in family, social, and working life (Abramson et al., 2015; Nardon et al., 2022; Tomono et al., 2021). Moreover, isolation has shown consequences on people’s mental health, especially for women reconciling work and family life under stressful circumstances (Adams-Prassl et al., 2020; Yavorsky et al., 2021).

According to Mucharraz y Cano and co-authors (2023) , work-related burnout was higher in mothers in leadership positions than fathers in similar roles, and this difference to could be due the caregiving role assumed by the mothers during this time. Burnout is defined as a psychological syndrome caused by overexertion or emotional exhaustion, depersonalization or cynicism, and lack of professional efficacy experienced by employees over a long time (Maslach et al., 2001). The consequences of burnout range from reduced work efficiency, increased likelihood of committing errors and low productivity, to serious health problems (Bakker & Costa, 2014; Colin-Flores, 2019).

Understanding the current state of the situation and addressing an aspect as important as mental health may enable the possibility to take actions, both at the public level and in the business and family environments, to promote well-being. Thus, the building of resilience at the social level comes from the necessity that human capital must be strengthened to accelerate the recovery process (Abramson et al., 2015). Therefore, adequate recovery from an adverse event, such as a pandemic, requires the activation of mechanisms taking on a process of learning and responsible change for the development of resilience (Duchek, 2020; Mucharraz y Cano, 2021).

The importance of the present research lies in its theoretical contribution, which introduces the concept of “burnout resilience.” This term aims to identify mechanisms or ways to support that would lessen burnout and promote adaptive mechanisms among executive mothers facing extreme conditions, both in their professional and personal lives, and the levers that influence the development of resilience that may also appear after the crisis ends.

This study aimed to investigate whether pandemic conditions led to higher levels of burnout among women compared to previous circumstances. Additionally, it sought to examine the potential influence of structural, organizational, and familial support in the development of burnout resilience.

2. Theoretical Background

The objective of this research was to understand how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the level of burnout among executive mothers in their roles as both professionals and mothers, considering some support that could attenuate burnout. For this study, the hierarchical positions considered were: C-Suite, CEOs, owners, vice presidents, senior managers, or similar, occupied in public or private organizations. Therefore, by generating a quantitative analysis through indicators that allow for a review of the level of depletion before and during the pandemic, it will in turn be possible to adequately assess the dimension of the problem to make decisions and take the corresponding actions in future crises.

The challenges derived from the COVID-19 pandemic “stripped away a facade that hitherto largely obscured structural cracks in society” (Rouleau et al., 2021, p. 245), especially for vulnerable groups, including women (Rouleau et al., 2021). In this sense, work and family implications started to gain attention, where the initial conclusions from some scholars showed that gender inequalities in both family and work deepened with the pandemic (Yavorsky et al., 2021).

This study considered the sociology of disasters since the COVID-19 pandemic, which can be classified as such; moreover, the reference to literature on disasters and social inequalities seems applicable (Reid, 2013). In this context, work-life conflict adds another layer of complexity to the already difficult job demands that individuals face and the potential effects on mental health that have been described since the seventies (Karasek, 1979).

Karasek (1979) provided the foundations for the job-demand-control-support (JDCS) theory, in which mental strain can be predicted based on the interaction of the demands and decisions required in the workplace to achieve work satisfaction. In other words, Karasek proposed a stress-management model in which job demands and low job decision latitude were associated with mental strain and job dissatisfaction. Based on this literature, the approach we decided to adopt was referred to job demands, which were related to the mental stressors and sleep disturbances associated with a potential unexpected increase in the workload derived from the COVID-19 pandemic, and how they were linked to job-related personal conflict (Ballesio et al., 2022). As suggested by Karasek (1979), mental strain is associated with exhaustion and depression, the former being a variable that we considered as we explored burnout during the pandemic.

Additionally, as the workforce composition has been modified with the increase of the active participation of women in the economy, gender studies focused on working women have underlined the difficulties concerning work-life or work-family conflict (Darouei & Pluut, 2021; Martins et al., 2002; Robinson et al., 2016) and the need to moderate burnout through the development of resilience (Gupta & Srivastava, 2021). For this reason, the present study will take elements from the JDCS theory, recently applied to work-life conflict and burnout among working women by some scholars (Gupta & Srivastava, 2021), analyzing and adding some elements derived from the COVID-19 pandemic and the development of resilience in the face of extreme events (Mucharraz y Cano, 2020).

Previous research by Gupta and Srivastava (2021) uncovered the variables that interact with work-life conflict and burnout as well as their moderators, including organizational and family support and the development of resilience. In this sense, and building on the aforementioned literature, work-life conflict can be considered a pre-existing condition that preceded the impact of COVID-19, and its influence on burnout could have aggravated the disaster impact.

Burnout

Burnout is a condition resulting from inadequate management of job stress by workers over a prolonged time (Maslach et al., 2001). In their recent work, Manrique-Millones et al. (2022) suggested that burnout is a condition related to chronic stress and the lack of resources to cope with it. Burnout is a multidimensional syndrome characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and professional efficacy as the self-perception of reduced personal accomplishment (Maslach & Jackson, 1981). In contemporary decades, considerable scholarly endeavor has been devoted to elucidating the dynamics of workplace stress and formulating mitigative strategies aimed at enhancing mental well-being within organizational settings (Schaufeli et al., 2017).

Maslach and Jackson (1981) have identified burnout in different sectors, jobs, and roles, including the family sphere and parenting, although not all scholars supported the transference of the concept to other occupations (Schaufeli et al., 2017). Burnout has also been investigated in disaster situations, such as the 9/11 terrorist attack in New York, where it was found that people with greater preparedness in crises tended to have lower burnout (Brooks et al., 2020).

Organizational Support and Family Support

In the model proposed by Gupta and Srivastava (2021) , there are two support that moderate work-family conflict and burnout: organizational support and family support. On one hand, family support, seen as activities in which family members collaborate, or paid domestic help, especially spousal support, has been considered in studies about work-family support. On the other hand, organizational support could be seen as good job conditions, welfare programs, rewards, and flexible time schedules, among others. It has been shown that organizational support and family support moderate the work-life conflict experienced by working women; when they are present, the overall impact might decrease burnout.

Previous research on work-life balance underlined the importance of organizational and familial support (Frone et al., 1992; Goodman & Kaplan, 2019; Gupta & Srivastava, 2021; Martins et al., 2002; Nohe et al., 2015). In this sense, organizational resilience theory also indicates that having strategies for building resilience in crises is a way to achieve business sustainability (Bachtiar et al., 2023).

In the context of disaster resilience, which can be applied to the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, organizational and family support also seems to be aligned with the main resilience attributes at the individual level, in which social capital involves family, friends, and coworkers as part of the perceived social support (Abramson et al., 2015; Bellanti et al., 2021; Brooks et al., 2020). Organizational support has also studied job and family dissatisfaction and stress as well as other mental health issues concerning anxiety and depression (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). The work-family role pressure model suggested by Greenhaus and Beutell (1985) considered the impact of extended working hours and inflexible work schedules and the misalignment of expectations in role pressures and the demands in the family domain.

With the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic the situation changed for the worse because of the increase in job and family demands, especially for executive mothers (Yavorsky et al., 2021). Despite the benefits of telecommuting, which allowed for the continuity of businesses during the pandemic, for some jobs the number of working hours increased, so that the need for total availability with the use of technology seemed to be the norm, at the expense of workers’ mental health. Companies and management could potentially be abusive, violating employees’ human rights and falling into illegal practices that could be regarded as a form of exploitation and might even be classified as modern slavery in some cases (Crane, 2013). Modern slavery has been applied to management, and it is defined as “the status or condition of a person over whom any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership are exercised” (Crane, 2013, p. 50).

Resilience

The concept of resilience has been studied for more than 40 years in academia, but the last 20 years have been the most fruitful with an eightfold increase in research (Boniwell et al., 2023). Even so, there is still a lack of consensus on a single definition; all of them seem to include the development of an adaptive capacity to a change or a positive adaptation despite adversity (Brooks et al., 2020; Paton & Johnston, 2006), especially in the face of crisis or disaster (Duchek, 2020; Leiter & Maslach, 2016; McLachlan et al., 2020; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 2021; Quintanilla, 2012). From a societal point of view, resilience is a process where society or communities respond efficiently and seek ways to avoid future losses from similar disasters (Bachtiar et al., 2023; Noy & Yonson, 2018).

Therefore, resilience is essential to build individuals and societies better prepared to cope with disasters (Khan et al., 2022) or crises because enhancing individual resilience has been associated with mitigated psychological distress, decreased anxiety, and alleviated depressive symptoms. Similarly, within organizational settings, strengthening resilience is associated with increased work performance, improved mental well-being, and the promotion of positive work-related attitudes (Boniwell et al., 2023).

Introducing the construct of resilience from Gupta and Srivastava’s model (2021) allows connecting the concept with the literature on disaster resilience, which can add new elements to address the issue of work-life conflict in the face of a catastrophic environment like the COVID-19 pandemic. The concept will be applied to individuals, as this is the unit of analysis of the present study.

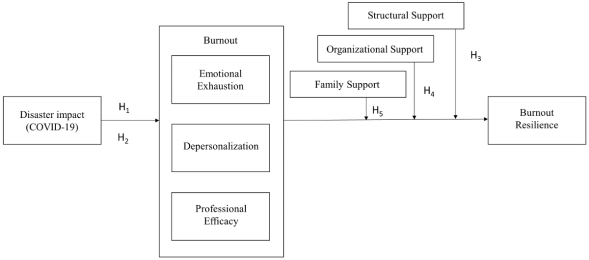

The hypotheses developed after reviewing the literature are presented here.

H1: Levels of exhaustion and depersonalization were higher during the pandemic compared to pre- pandemic periods, while the level of professional efficacy experienced a decline amidst the impact of COVID-19.

The first premise is supported by the JDCS (Karasek, 1979; Reid, 2013) and disaster resilience literature (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985; Gupta & Srivastava, 2021; Karasek, 1979; Martins et al., 2002; Nohe et al., 2015) and emphasizes the effect of the disaster in the prevalence of burnout as described by McLachlan et al. (2020) . To measure burnout, three variables were considered in the Maslach burnout inventory (MBI): (a) exhaustion, (b) depersonalization, and (c) professional efficacy (Maslach & Jackson, 1981).

The MBI survey provided the necessary elements to measure work burnout (Leiter & Maslach, 2016) and identify the demographic characteristics of executive mothers. The parameters to observe if burnout was high or not were compared to previous studies that used the MBI scale, including those in the Mexican population (Quintanilla, 2012).

H2: Burnout in executive mothers is higher under the COVID-19 pandemic confinement than under regular conditions.

Structural support was not a variable included in the model from Gupta and Srivastava (2021) or previous research, and it is one of the contributions of this study. For this research, structural support is a distinction defined as child monitoring by someone outside the family, which could be provided by governmental, civil, or private institutions. The structural support considers the possibility of children attending school, having access to daycare, and for those with the possibility to allocate resources, having paid aid. The need to include this variable was observed as critical, considering that in some countries, including Mexico, schools were closed for more than 200 days (OECD, 2021), and changes in daycare access also interrupted the possibility of having this support. Also, the concept of burnout resilience (BR) was not found in previous studies, and the possibility of introducing it responded to the necessity to name a trait that reconciled two apparently antagonistic constructs: (a) burnout and (b) resilience, which are similar to the concept of disaster resilience (Abramson et al., 2015). This reconciliation could illustrate the development of an adaptive capacity to face a chronic or acute burnout condition, characterized by both a systemic and an individual response to address emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a self-perception of reduced professional efficacy from a structural perspective and not only refer to the individual’s resilience attributes. The reference to a structural perspective contemplates three subsystems that may influence individual and community mental health. This distinction BR provides is a resilient response (Abramson et al., 2015) at macro and micro levels simultaneously: capable governance or structural support, the organization, and the family.

H3: The development of BR is influenced by structural support.

The conceptual model considered as a reference for this research has already accounted for organizational support as a moderator for burnout that could potentially increase resilience to work-life conflict (Gupta & Srivastava, 2021). The workplace has led to the identification of factors that could help alleviate stress and the negative side effects of work demands (Boniwell et al., 2023). Factors previously described to mitigate work-family conflict included workplace environment, managerial and peer support, and flexible working hours, which can be associated with job contentment and performance (Khursheed et al., 2019; Orel, 2019). For this category, we considered three main elements that may illustrate organizational support: (a) work arrangement (like home-office or flexible time); (b) income (benefits to pay for babysitters or afterschool activities); and (c) hierarchical level (as executive positions that may represent higher levels of burnout in the organization) to understand if any or all these elements have any influence on burnout.

The hierarchical level is a complex element, as it depends on other factors to be attained, but it is related to the previously used element regarding the management level achieved (Martins et al., 2002). We added this variable because the limitations in career opportunities for women to progress are well-known, and previous studies that addressed work-family conflict and career satisfaction provided insight into this matter (Frone et al., 1992; Martins et al., 2002; Nohe et al., 2015).

H4: The development of BR is influenced by organizational support.

Family support has previously been studied to understand the dynamics inside the household and parental responsibilities (Goodman & Kaplan, 2019; Khursheed et al., 2019). It is relevant to consider cultural aspects because, in some countries, the woman in the family is expected to act as the primary caregiver and is in charge of domestic chores.

Finally, the work-family conflict has been studied about the role women play inside it (Frone et al., 1992); the potential moderators, including family support (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985; Ren et al., 2021); and the development of resilience (Gupta & Srivastava, 2021) as part of the social resources to face a complex environment (Mucharraz y Cano, 2021). This variable was measured with a direct question about having support from a partner, family, or friends in caring for children throughout the pandemic.

H5: The development of BR is influenced by family support.

3. Methodology

The research used an online survey of female executives where job burnout was measured through the MBI. The data analysis for the hypothesis tests were comparison of means by paired t-test, mean test by one-way analysis of variance and comparison of means with t-test. The methodology used is explained in more detail below.

Design and Procedure

This study used a quantitative method, and a non-probability snowball sampling was carried out. The complete questionnaire was pilot-tested in May to ensure proper wording and comprehension of the items. The survey was conducted in Mexico during June, July, and August 2021. The participants were assured anonymity, and they did not receive payment or any other incentive for responding. Other research on burnout in specific occupational groups used similar or smaller samples (Darouei & Pluut, 2021; Gupta & Srivastava, 2021; Matsuo et al., 2021; Quintanilla, 2012).

For the job burnout section, this research followed the methodology established by Maslach and coauthors (2016) through the application of the licenced Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS), which has been validated for different occupational groups and nations (Mäkikangas et al., 2011). However, there are other less commonly used instruments, such as the Pines burnout measure, the Copenhagen burnout inventory, or the Oldenburg burnout inventory, that could be used. The job burnout measure is a formative variable with three dimensions:

Exhaustion that implies energy depletion (higher exhaustion implies higher burnout).

Depersonalization or cynicism that is reflected as personal and professional detachment (higher depersonalization implies higher burnout).

Professional efficacy as lack of professional fulfilment or accomplishment (higher professional efficacy implies lower burnout).

For the calculation of data and variables, we used version 14.2 of the statistical software STATA.

Participants

The online survey was disseminated after an open invitation; three Graduate Business Schools invited their women graduates with children to answer the survey via WhatsApp and e-mail. The number of surveys received was 1,279, but from this universe of responses, only 704 completed the questionnaire and met the selection criteria, such as having children and being an executive.

Instrument

The self-directed survey was composed of four sections: the first corresponded to informed consent, the second collected demographic and work information, and the third contained the 16-item MBI-GS with the 7-point Likert scale included in the MBI manual (Maslach et al., 2016), a psychometrically-validated instrument to measure the frequency of each statement. The Linkert scale was 0 = never to 6 = every day. This method used the mean as a form of calculation for each of the variables-exhaustion, depersonalization, and professional efficacy. The license fee to use the MBI-GS scale was paid on 18 October 2021 by Mind Garden. The final section included additional questions regarding the pandemic.

It is important to note that for the additional questions that were not part of the MBI, the results need to be considered with caution. They have not been previously validated, as the pandemic presented a contingent situation not found in previous literature.

The survey was in Spanish, where there is no exact translation for the word burnout. The decision was made with the support of the literature in which previous studies have used the terms burnout and stress interchangeably because they share common causes such as pressure at work and conflicts at home, among others (Otto et al., 2021). However, among the main distinctions between the two terms was the long-term effect of burnout due to the prolonged exposure especially of job stressors and the chronic condition it represents conceptually (Schaufeli et al., 2017).

The analysis of the MBI’s 16 items measured the three subscales of burnout: (a) exhaustion, (b) depersonalization, and (c) professional efficacy. The demographic and labor information intersected with most of the variables derived from Gupta and Srivastava’s (2021) conceptual model, which considered family support and organizational support. We observed the need to add some elements external to family support, which were introduced in the model as structural support. As previously mentioned, the elements considered in this category included school, daycare, and paid support for child monitoring, as during the pandemic these elements seemed to be critical to support working mothers and children. In the organizational support category, three elements were taken into consideration: the first one was the work arrangement, to observe if telecommuting or hybrid schemes helped women to carry out their work and household chores more easily; the second element was the income; and the third one was the type of job and the hierarchical level in the organization.

The conceptual model depicted in Figure 1 illustrates the effect of the COVID-19 disaster on burnout, highlighting the influence of structural support, organizational support, and familial support, which ultimately lead to burnout resilience.

Data Analysis

Cronbach’s alpha was used to test the consistency with a scale reliability coefficient of 0.7 for all the variables used. The significance levels of the hypotheses were tested through three methods: (a) comparison of means by paired t-test, (b) mean test by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and (c) comparison of means with t-test. The second hypothesis was verified by comparison of means by paired t-test because executive mothers reported their perception of stress before and during the pandemic on the survey. For the third and fifth hypotheses, ANOVA was required to check for normality, independence, and homoscedasticity, to which the Leneve and Barlett tests were used. The third hypothesis related structural support to each burnout variable, while the fifth hypothesis was run against familial support. Finally, the fourth hypothesis had to carry out a comparison of means with a t-test, because heteroscedasticity was detected. The hypothetical mean used in the comparison was the upper mean of professional efficacy by subgroup: (a) work arrangement, (b) income, and (c) hierarchical level.

4. Results

As shown in Table 1, levels of burnout and depersonalization were higher in the pandemic than before; the differences were 0.52 and 0.88 respectively while professional efficacy decreased by 0.21. These three results led to the conclusion that the overall burnout level was higher in the pandemic than in previous periods.

Table 1: Levels of Exhaustion, Depersonalization, and Professional Efficacy among Working Mothers During the COVID-19 Lockdown

| Variables | Observations | Mean | Standard Deviation | Reference Meana | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exhaustion | 704 | 3.09 | 1.46 | 2.57 | 0.52 |

| Depersonalization | 704 | 1.79 | 1.29 | 0.91 | 0.88 |

| Professional efficacy | 704 | 4.94 | 0.85 | 5.15 | -0.21 |

Note. a Reference mean for women with executive positions (Quintanilla, 2012).

To determine with greater certainty whether women were found to have higher levels of burnout, the survey asked about the perception before and during the pandemic. Table 2 shows that there was a higher level of stress during the pandemic. Through the comparison test of means before and during the pandemic, it was confirmed that the mean of work stress before (µ = 6.7) was significantly (p < 0.001) lower than that of work stress during the pandemic (µ = 7.69).

Table 2: Means Comparison by Paired t-test: Work Stress Before and During the COVID-19 Lockdown among Working Mothers

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work stress before the pandemic | 704 | 6.70 | 2.11 |

| Work stress during the pandemic | 704 | 7.69 | 2.27 |

| Difference | 704 | -0.98 | 2.31 |

| t = -11.2896a |

Note. t is the value of the t-test; a p < 0.001

Table 3 shows four possible scenarios of the existence of structural support: (a) having it before and during the pandemic, (b) having it before but losing it in the pandemic, (c) accessing it during the pandemic, and (d) never having structural support. Structural support did have a significant impact (p < 0.001) on the variable exhaustion; however, it had no significant effect on depersonalization and professional efficacy.

Table 3: Mean Test by One-Way ANOVA. Burnout Variables against Structural Support

| Exhaustion | Depersonalization | Professional Efficacy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup | N | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Structural support before & during pandemic | 169 | 3.09 | 1.42 | 1.76 | 1.21 | 4.97 | 0.82 |

| Structural support only before the pandemic | 163 | 3.37 | 1.46 | 1.89 | 1.28 | 4.94 | 0.82 |

| Structural support during the pandemic | 58 | 3.47 | 1.33 | 1.97 | 1.36 | 4.82 | 0.80 |

| Never had structural support | 314 | 2.87 | 1.47 | 1.72 | 1.31 | 4.95 | 0.90 |

| Significance level F | 5.85a | 0.99 | 0.43 | ||||

Note. N = Observations, M = Mean, and SD = Standard Deviation; a p < 0.001

Specific note. Each burnout variable (Exhaustion, Depersonalization, and Professional Efficacy) was tested by one-way ANOVA against structural support by subgroup.

Table 4 shows three types of organizational support: (a) work arrangement, (b) income, and (c) hierarchical level. In this case, all support influenced the burnout experienced by executive mothers (p < 0.001, p < 0.01).

Table 4: Comparison of Means t-test of Professional Efficacy by Hierarchical Level, Income Level, and Work Arrangement

| Variable | Subgroup | Observations | Mean | SD | t-test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hierarchical Level | Managerial | 174 | 4.73 | 0.92 | -4.08a |

| Head of a section | 155 | 5.09 | 0.75 | ||

| CEO or business owner | 170 | 5.12 | 0.75 | ||

| Other Levels | 196 | 4.76 | 0.91 | -5.62a | |

| Reference mean: CEO or business owner 5.12 | |||||

| Income level | > 25,000 pesos | 187 | 4.79 | 0.90 | -6.29a |

| 26,000-34,000 | 135 | 4.86 | 0.90 | -4.43a | |

| 35,000-64,000 | 159 | 4.87 | 0.91 | -4.63a | |

| 65,000-95,000 | 90 | 5.14 | 0.72 | ||

| < 95,000 | 132 | 5.20 | 0.67 | ||

| Reference mean: Above 95,000 MXN pesos 5.2 | |||||

| Work Arrangement | Full-time at the office | 74 | 5.05 | 0.89 | |

| Part-time at the office | 36 | 4.69 | 1.05 | -2.28b | |

| Full-time home office | |||||

| 364 | 4.91 | 0.86 | -3.99a | ||

| Part-time home office | 102 | 4.87 | 0.83 | -2.64b | |

| Hybrid | 127 | 5.09 | 0.76 | ||

| Reference mean: Hybrid 5.09 | |||||

Note. a p < 0.001, b p < 0.01

Finally, the results did not show a significant difference for the three subcategories that measure burnout: (a) exhaustion, (b) depersonalization, and (c) professional efficacy with familial support (Table 5).

Table 5: Mean Test by One-Way ANOVA. Exhaustion, Depersonalization, and Professional Efficacy Against Family Support.

| Exhaustion | Depersonalization | Professional Efficacy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Subgroup | N | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Family Support | Yes | 579 | 3.07 | 1.46 | 1.77 | 1.29 | 4.94 | 0.85 |

| No | 125 | 3.15 | 1.47 | 1.88 | 1.26 | 4.94 | 0.89 | |

| Sig. Fisher Test | 0.26 | 0.81 | 0.00 | |||||

Note. N = Observations, SD = Standard Deviation, and Sig = significance

5. Discussion

The H1 and H2 hypotheses were confirmed after analyzing the MBI results. As expected, burnout was higher during the pandemic than before; exhaustion and depersonalization were higher, and professional efficacy was lower. The results of this study confirmed that burnout among executive mothers increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. This can be explained primarily because it is to be expected that the abrupt appearance of COVID-19 and the change it generated in the lives of humanity, including executive women, generated an unusual level of mental strain, which has also been studied previously (Matsuo et al., 2021; Polizzi et al., 2020).

H3, which analyzed the structural support that is our contribution, showed an influence on the exhaustion variable of burnout; however, structural support does not affect professional efficacy nor depersonalization. In other words, the possibility of children attending school, having access to daycare, and, for those with the possibility to allocate resources, having paid aid helps mothers to have more energy to work. However, it did not affect their performance in the workplace, and it did not lead to a job detachment. The results obtained for the third hypothesis regarding structural support as an influential factor in the development of resilience require careful analysis. The connection between the cultivation of resilience and the relief of burnout seems to be affected by the provision of structural support. Nonetheless, grasping the context is crucial for interpreting the data accurately. The women in the sample experienced a total lockdown, without schools and with reduced access to day-care facilities, as the number of fully closed or partially open instructional days in Mexico was the highest in the report by the OECD (2021), consisting of 214 days between 2020 and 2021, including pre-primary, primary, and lower- secondary education. It is very common for the middle class in Mexico to have paid aid to support families with household responsibilities as well as after-school activities. During the pandemic, paid aid was limited due to the sanitary contingency (i.e., preventive and isolation measures) and the economic crisis (Jiménez-Vargas et al., 2021).

When we observe an increase in the levels of exhaustion about structural support, what the results may be reflecting is that (a) women who had external aid before the pandemic but lost this support and (b) those who did not have support but required it during the pandemic to cover the lack of structural support (e.g., schools and day-care) experienced more burnout. A potential explanation may be that the stress of a modified reality was added to an increase in job demands and a low job-decision latitude, in which mental strain and exhaustion were expected, as confirmed by the JDCS theory in previous research (Karasek, 1979).

The H4 hypothesis was confirmed, as women’s work arrangement, income, and hierarchical level (position) in the organization made a difference when comparing the burnout subcategory of professional efficacy with these variables. Executive mothers with organizational support reported lower levels of exhaustion on their mental health, and this type of support may be a protective factor against burnout. For organizations contribution to this element of well-being, it is convenient to analyze the possibility of implementing more childcare support conditions for executive mothers in their organizations. These sorts of benefits sparked positive emotions that researchers found to be important for resilient outcomes. Organizations have the responsibility of helping with gender diversity and offering conditions that allow women to have a better work-life balance. These initiatives may include daycare for children and flexible or hybrid working arrangements. In addition to this, organizations can benefit from branding to attract, engage, and retain female talent. The objective of employer branding is to develop the organization’s brand to engage employees and stakeholders and try to minimize employee attrition in the organization (Backhaus & Tikoo, 2004). Many organizations are recognizing the potential of employer branding and are implementing work-life programs to avoid turnover and decreased productivity; therefore, they are relevant for the retention and attraction of valuable workers.

Family support was not significant in this study. This phenomenon may stem from the circumstances of isolation, which have prompted nuclear familial units to spatially disengage from proximal relatives, notably grandparents, aunts, and uncles, who often serve as other sources of support.

6. Conclusion

This study contributed to a better understanding of how the COVID-19 pandemic caused a major shift for executive mothers and how they experienced burnout effect during it. As it is well known, the pandemic has led to a dramatic increase in stress (Journault et al., 2022) and therefore there is a need to revert the negative impact caused through an adaptive mechanism we referred to in the paper as burnout resilience. Women workers have experienced exhausting workdays, and it is critical to identify the threads that facilitate the way toward a relief of burnout. We cannot ignore the fact that this responsibility must be shared in a cross-sectoral way, with governmental involvement generating better public policies in favor of executive mothers, organizations, and the civil society.

Companies need to think more broadly about their responsibility toward the mental health of their employees, not just to guarantee productivity but to secure lower burnout levels. There is a need to promote and support executive mothers not only in crisis but also in the day-to-day activities, through the implementation of policies, childcare, and better benefits from micro and macro perspectives. Chrobot-Mason et al. (2021) argued that without affordable childcare and due to stereotypes, mothers have a more difficult path in their careers. After studying some conceptual models that deal with the complexity of work-life conflict, burnout, and its moderators described previously, we can conclude that the development of resilience is critical to addressing burnout effects in executive mothers, and it depends not only on their personal circumstances and capabilities, but also from the structural support that relies on the macro and meso-societal structures. Family involvement did not appear to be statistically significant in this study and the potential reasons seem to be related to the particular conditions of the COVID-19 confinement. In sum, organizational support and structural support are required in the post- pandemic stage and in the future to promote the development of burnout resilience in executive mothers.

7. Limitations and Further Studies

It is necessary to study the long-term effects that executive mothers experiencing high levels of burnout can have on society, and responsibly address them. The survey was conducted in Mexico, but it is necessary to contrast these results with similar research in other countries. This study was conducted with women working in executive positions, and this study can be replicated with female workers in different hierarchical levels that are not necessarily managerial but spread across the organization. In the same way, it is necessary to investigate the effects of familial support in other cultures or societies that are more individualistic and less collectivist, taking more into consideration a contrast between cultures, to understand if the development of burnout resilience relies on culture.

Disclosure

Approval of the research protocol: Approval was received from the IPADE Business School Directorate of Research on June 3, 2021. All research participants provided informed consent, which was included in the digital survey. The Maslach Burnout Inventory-General remote online survey license was obtained on October 18, 2021, by Mind Garden. Animal studies were N/A. Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest for this article.