1. Introduction

Unlike businesses that operate outside the family context, family businesses are distinguished by unique socio-emotional elements. Numerous studies have demonstrated that decisions in family businesses are influenced by affective factors rooted in familial relationships between the parties involved (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011). Family business owners derive socio-emotional wealth (SEW) from various sources, such as the connection between their surname and the company, the emotional attachment to it, and the satisfaction of family members employed by it (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011). Moreover, they seek utility by preserving the SEW generated by the non-economic aspects of the company (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). However, as one of the responsibilities of family businesses is to maintain and increase the SEW of the owners, its preservation can have an impact on the business decisions of both the family owners and the managers of the business (Martin and Gómez-Mejía, 2016). Research suggests that a family’s desire to preserve social-emotional wealth can have both positive and negative impacts on the long-term performance of family businesses, including their ability to innovate.

While it is true that family businesses have traditionally been seen as resistant to change and adhering to conservative values (Dunn, 1996), recent research has revealed that these firms can also be valuable contributors to innovation initiatives. For instance, family businesses can serve as drivers of technological innovation (Gudmundson et al. 2003; Zahra 2005). This is particularly noteworthy given the importance of innovation for the long-term survival of family firms (La Porta et al., 1999; Villalonga & Amit, 2009). However, our understanding of innovation in this context remains incomplete and sometimes contradictory (Hauck & Prügl, 2015).

It is widely recognized that innovation can result in the creation of competitive advantages (Porter, 2011) and plays a critical role in the performance of family businesses (Kellermanns et al., 2012). Indeed, innovation is essential for the long-term survival of family firms (Schumpeter, 1983). Innovative activities serve as a means of adapting to change and seizing it as an entrepreneurial opportunity (Craig & Dibrell, 2006; Drucker, 1985). The need to survive through innovation has become increasingly apparent for family businesses aiming for long-term success across generations (Cruz & Nordqvist, 2012). Entrepreneurial orientation (EO) is essential in this context, as it refers to an individual’s ability to identify and pursue opportunities, drive change, and respond with flexibility and openness. EO and innovation are crucial for the success and survival of family businesses, and business owners must embrace an EO mindset and be willing to innovate in all areas of their business to thrive in an ever-changing business environment. However, the transmission of EO has not been extensively explored in recent years (Arcand, 2012). The primary objective of this research is to show the critical role that the effective transmission of EO plays in maintaining SEW and the impact of both in the innovation of family businesses across generations.

The case study of Viveros Villanueva Vides, a family business in the wine and agricultural sectors based in Spain, offers an insightful exploration into how EO and SEW interact to foster innovation within a family firm context. The methodology employed in this study involved qualitative research to gain a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between EO and SEW. The use of thematic analysis and the critical incident technique further enriched the data analysis, revealing key insights into the innovative practices and milestones achieved by the company over time.

The findings from this case study underscore that the relationship between EO and SEW in family businesses is intricate and has significant implications for innovation. The dynamic interrelationship between EO and SEW is marked by a mutually reinforcing symbiosis. EO drives the positive influence on SEW by fostering a culture of innovation, adaptability, and opportunity-seeking within the family business. The SEW ensures the intergenerational transmission of EO by securing the family’s legacy and identity through successful business practices and innovations.

The Viveros Villanueva Vides case exemplifies how the intergenerational transmission of entrepreneurial values and practices can lead to sustained business success and competitiveness in a changing market environment. This is particularly evident in the company’s approach to maintaining the EO across generations, as well as its commitment to maintaining family control and emotional attachment, their SEW, to the business. It demonstrates that contrary to the notion that family businesses may be limited in their innovative endeavours, those that effectively transmit entrepreneurial values and foster a culture of long-term orientation can achieve remarkable innovation success and longevity.

The study is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a theoretical overview of the topic. Section 3 outlines the research methodology employed and Section 4 offers a summary of the key findings. Following this, Section 5 discusses the implications of the study, and the final section presents the main conclusions drawn from the research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Family Business and Socio-Emotional Wealth (SEW)

Research into family businesses has experienced a significant upsurge in recent years, which can be attributed to the substantial number of family businesses that exist within the global economic system. In our country, these businesses comprise approximately 90% of all companies, contribute 60% to gross value added (GVA), and account for 70% of private employment, as reported by the Family Firms Institute in 2020.

Despite its growing significance, the field of family business studies remains relatively nascent (Litz et al., 2012) and inadequately examined (Astrachan, 2010). This gap in research is largely due to the distinctive behaviour of family businesses, which differs from that of non-family firms (Astrachan, 2010; Benavides-Velasco et al., 2011; Chrisman et al., 2010). The defining characteristic of family firms is the presence of family involvement in the business (Chua et al., 2012), and what sets them apart is the family’s active participation in management (Handler, 1989; Miller & Rice, 2013).

Therefore, despite the difficulty in reaching a consensus definition due to the extensive conceptualization of family firms (Upton et al., 2001), it can be said that these businesses are characterized by ownership and control being mostly in the hands of a family, and at least two family members being involved in the management of the company (Rosenblatt et al., 1991).

In order to establish academic credibility in this field and develop new theories that would capitalize on the unique aspects of family business research, researchers have been called upon (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011). While some studies have been conducted, none have yet become dominant (Carney, 2005; Gedajlovic et al., 2012; Lubatkin et al., 2005; Schulze et al., 2003). However, there is a growing belief that SEW is becoming the prevailing perspective in family business due to its consideration of non-economic and non-financial factors (Berrone et al., 2012).

SEW is a key differentiating factor between family and non-family businesses, as it encompasses the non-economic aspects of business that fulfil the affective needs of the family, such as identity, the ability to exert family influence, and the perpetuation of the family dynasty (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). The SEW model, based on the theory of behavioural agency (Wiseman & Gómez-Mejía, 1998), aims to demonstrate the emotional value that families invest in their companies (Berrone et al., 2010).

2.2. Socio-Emotional Wealth and Innovation

SEW refers to the non-financial aspects of a business that family owners highly value, such as their emotional attachment, identity, and the desire to maintain family control over the firm (Berrone et al., 2012). SEW captures the affective endowment of family owners, encompassing desires like exercising authority, enjoying family influence, maintaining clan membership within the firm, appointing trusted family members to important posts, retaining a strong family identity, and continuing the family dynasty, among others (Berrone et al., 2010; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011). SEW is considered a multidimensional construct, integral to understanding the unique behaviours and decision-making processes within family firms, differentiating them from non-family firms (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007; Hauck & Prügl, 2015; Makó et al., 2018). Despite its significance, challenges exist in measuring SEW directly due to its latent nature, necessitating further research to better capture its dimensions and behavioural consequences. According to Berrone et al. (2012); the dimensions of SEW are encapsulated in the FIBER framework, which stands for:

1. Family control and influence. This dimension emphasizes the control and influence exerted by family members over the firm, allowing them to steer the firm according to their values and vision; 2. Identification of family members within the firm. This aspect highlights the degree to which family members identify with the firm, seeing its success and reputation as reflective of their own; 3. Binding social ties. This dimension refers to the strength of social relationships within the firm, fostering a sense of belonging and mutual support among family members. 4. Emotional attachment of family members. This dimension captures the emotional connections family members have with the firm, which can significantly influence decision-making processes. 5. Renewal of family bonds to the firm through dynastic succession. This aspect focuses on the intention and actions taken to ensure the continuity of family involvement in the firm across generations. These dimensions collectively represent the unique blend of affective and instrumental considerations that family firms prioritize, differentiating their strategic decision-making processes from those of non-family businesses (Hauck & Prügl, 2015).

Consequently, numerous family business researchers have examined this concept and its impact on the behaviour of these firms (Chrisman et al., 2010; Wiseman & Gómez-Mejia, 1998; Xi et al., 2015). However, scholarly opinions on the matter are not unanimous, with some academics arguing that certain SEW components, such as a stronger company commitment or long-term orientation, may positively influence performance, while others, such as nepotism or favouritism, may have a negative impact (Martin & Gómez-Mejía, 2016).

This disparity stems from the fact that the preservation of SEW is of paramount importance in family business decision-making (Berrone et al., 2012; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). In fact, owners of these organizations are often willing to take financial risks to safeguard SEW, which can lead to an aversion to growth and a slow decision-making process (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). As a result, family businesses are often characterized as being conservative and displaying a preference for maintaining the status quo over pursuing aggressive growth strategies (Habbershon et al., 2003).

The presence of psychological barriers can impede the progress of family businesses when an opportunity has been identified (Debellis et al., 2021). Notably, innovation is a significant means of achieving a competitive advantage (Lohe & Calabrò, 2017). However, making the decision to engage in innovative behaviour can be complicated for family businesses due to their unique characteristics (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007).

For instance, family ownership can limit a business’s ability to invest in innovation, resulting in capital constraints that make it difficult to allocate resources to this endeavour (Carney, 2005). Family businesses often bear the costs of failure, as business is not only the source of livelihood but also the very essence of the family (Block, 2011). Therefore, family members may be reluctant to adopt new strategies, as they develop emotional attachments to the company’s original plans (Vago, 2004). These emotions can hinder the exploration of new opportunities, causing family businesses to stagnate if they fail to generate innovative ideas.

2.3. Entrepreneurial Orientation and its role in innovation

In this section, we examine the inherent connection between EO and innovation in the context of family businesses. Family businesses, with their rich history and strong cultural identity, confront distinct obstacles in their quest for growth and long-term viability in a continuously evolving business landscape. EO and innovation are crucial for these companies to maintain their competitive edge and relevance (Leite et al., 2015).

EO is a firm’s strategic posture towards entrepreneurship and has become the predominant construct of interest in strategic entrepreneurship research (Anderson et al., 2015; Hernández-Ramírez et al., 2021). Within this field, EO is considered a theoretical perspective that has been identified as fruitful in understanding the dynamics within entrepreneurial families and family firms (Cruz & Nordqvist, 2012). This concept focuses on how businesses approach entrepreneurial activities, emphasizing the importance of innovation, proactiveness, and risk-taking in driving firm performance and competitiveness (Anderson et al., 2015; Capelleras et al., 2018; Parra et al., 2017). These dimensions have been found to vary independently within firms, suggesting that high-performing entrepreneurial firms do not necessarily exhibit high levels of all the EO dimension (Cruz & Nordqvist, 2012; Dess & Lumpkin, 2005).

Research has shown that maintaining or increasing levels of EO over time is crucial for firms to accrue long-term performance benefits (Arcand, 2012; Lumpkin & Brigham, 2011). In the context of family businesses, the use of EO dimensions varies, and has greater significance for transgenerational EO. This suggests that while EO is beneficial for long-term management and performance, the importance of its dimensions may differ across family firms, thus EO is often associated with leaders and founders who strive to grow and diversify the business, and who pass on this mindset to future generations (Arcand, 2012). In first-generation family firms, the founder plays a vital role in shaping the firm’s EO, as the founder with their vision, decisions, and actions directly influencing’s vision, decisions, and actions directly influence the firm’s approach to entrepreneurship (Lumpkin & Brigham, 2011). The family firms that promote EO among their members and employees are better equipped to face challenges and capitalize on new opportunities (David, 2009).

As the business transitions to second- and third-generation family firms, the influence of the founder on EO diminishes and becomes more indirect. In second-generation family firms, EO is more influenced by the Chief Executive Officer’s (CEO) interpretations of the competitive environment, reflecting a shift towards external factors shaping the firm’s entrepreneurial activities (Cruz & Nordqvist, 2012). By the time the firm reaches the third generation and beyond, access to non-family managerial and financial resources becomes a more significant driver of EO, indicating a further shift away from the direct influence of the founder towards a reliance on broader organizational capabilities and external resources to sustain EO (Cruz & Nordqvist, 2012).

2.4. The connection between EO and SEW and their impact on innovation

In the preceding sections, we have examined the independent roles of SEW and EO in driving innovation within family firms. However, the literature has little explored the relationship between these two variables and their influence on innovation. On the one hand, recent findings indicate that family firms emphasizing the preservation of SEW may undertake entrepreneurial activities that bolster their financial performance, utilizing SEW to amplify the effects of EO (Hernández-Perlines et al., 2021; Lasio et al., 2024). This underscores a nexus between EO, SEW, and firm performance, including innovation. Furthermore, it suggests that to cultivate EO, family firms must prioritize the augmentation of SEW (Hernández-Perlines et al., 2020). However, on the other hand, previous literature has demonstrated how SEW moderates the relationship between EO and financial performance (Schepers et al., 2014).

This EO and SEW dynamic, as posited by scholars, is still evolving and necessitates further investigation.

3. Methodology

3.1. Design

Qualitative research is a valuable tool for exploring the subjective experiences and behaviours of individuals within a specific target group. In this study, a qualitative methodology was selected due to its ability to delve deeply into the attitudes and EO of family businesses that have been passed down through generations, leading to increased value and innovation. To analyse the data, NVIVO software was utilized, allowing for the organization and coding of information.

The case study of “Viveros Villanueva Vides” offers a valuable perspective on transgenerational business growth and innovation. As Yin (1994) explains, the study’s design is unique due to its focus on the family interactions of a single business family. The study is descriptive in nature, aiming to describe the phenomena under investigation within the real-life context of the company and its environment. Additionally, the study is exploratory, as there is a theoretical framework in place, but limited research has been conducted on the relationship between EO, SEW, and innovation. The study’s approach and design involve a theoretical sample, in which family members who work at the company were interviewed to provide a generational, collective, and inclusive vision (Martínez, 2006).

In the context of family firm research, interviews constitute the most frequently utilized data source (Fletcher et al., 2016; Salvato & Corbetta, 2023). Semi-structured interviews are a preferred method in family firm research due to their flexibility and capacity to address specific issues while granting participants the autonomy to delve into their thoughts and beliefs (Hs, 2015; Qu & Dumay, 2011; Rowley, 2012). This approach is suitable when the researcher has some initial understanding of the sample’s circumstances concerning the research topic (Adeoye-Olatunde & Olenik, 2021).

Semi-structured interviews entail the utilization of a predefined set of inquiries (see Annex 1) supplemented by probing questions to gather additional information (see Annex 2), allowing the researcher to maintain a concentrated focus on the subject of interest while still having the discretion to explore other topics as needed. This approach yields dependable and comparable data and affords the researcher the latitude to pose follow-up queries, resulting in a wealth of detailed and nuanced data due to its open-ended nature and adaptability in asking probing questions (Ruslin et al., 2022).

Our methodology entails the integration of semi-structured interviews with direct observation or extensive analysis of secondary sources, such as magazines, interviews, websites, and social media, to cross-reference our findings and offer a comprehensive, external perspective on the case and the individuals involved.

3.2. Data analysis

The study utilized thematic analysis (TA) to analyse the results (Braun & Clarke, 2006). TA, derived from psychology, involves the identification, analysis, and interpretation of themes and patterns in empirical data (Escudero, 2020). This technique provides a detailed description and interpretation of the data set, while also offering a minimum organization of the data. The results section will reveal three analytical categories obtained through TA: innovation, socio-emotional wealth, and EO.

In addition, the critical incident technique (CIT) was employed to investigate the innovative practices of this family business across generations (Flanagan, 1954). CIT is a useful tool for identifying workplace solutions to problems and discovering labour practices that contribute to organizational success. In the results, 26 milestones are determined, which allow for an in-depth analysis of the contributions made over time that have driven various innovations within the organization.

3.3 Context of the research: Viveros Villanueva Vides

The genesis of Viveros Villanueva Vides traces back to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when the propagation of American vines commenced in Navarre, a region of Spain, following the phylloxera epidemic. This calamitous plague annihilated numerous vineyards, but the Larraga family perceived it as a favourable opportunity and opted to invest in this innovative venture.

The driving force behind the enterprise remained unwavering in his determination to prosper in this field, until the subsequent generation infused new vigour and a distinct business model, ultimately culminating in the fourth generation of vineyard cultivators within the family. As the adage goes, “Viveros Villanueva Vides is the result of the labour and character of several generations of the same family”.

The family’s unrelenting pursuit of improvement in the sector has propelled the company to acquire contemporary facilities and production equipment, thereby enabling the production of millions of grafts each season. Consequently, Viveros Villanueva Vides has emerged as a pioneer in the Spanish market and achieved progress in the international market.

This perpetual quest for betterment has spurred the company’s own research initiatives to enhance its production processes, simultaneously contributing to projects of mutual benefit to the entire sector.

3.4. Participants

Ten people participated in the study. The participants were chosen based on two considerations; the first was that the participants should be members of the family from different generations, and the second that they should have been involved in some way with the innovation processes of the company. In addition, the availability of the participants and their voluntary decision to participate in the study by means of informed consent were also taken into account. Among these participants, four of the five siblings of the third generation were interviewed. Each can provide valuable insights into the challenges and changes involved in joining a family firm in its early stages and passing on all the knowledge to the next generation. We also interviewed the six members of the fourth generation who currently play a key role in the company’s operations. The profiles of the participants are listed in the Table 1.

The eldest brother (Informant 1) was the first to join the family firm, helping his father in planting vineyards. The second brother (Informant 2) was in charge of preparing the soil and transporting the plants to customers, while the third brother (Informant 3) focused on vineyard-related tasks. The youngest brother (Informant 4) was in charge of the workshop work in the warehouse. Informant 5 dealt with overseas sales, communication, and marketing, while the informant 6 serves as the sales and technical manager. The informant 7 is responsible for land and sales, and informant 8, manages the fieldwork and vine grafting nursery production. The informant 9 handles sales and supports field operations, and the informant 10 focuses on vine management and graft selection. Each of these individuals is in a unique position to describe the challenges and opportunities they face in continuing their family’s legacy and driving innovation within the company.

Table 1: Presentation of the participants

| Informant | Current role in the company | Age | Generation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Member - Retired | 86 | 3ª |

| 2 | Member - Retired | 80 | 3ª |

| 3 | Member - Retired | 75 | 3ª |

| 4 | Member - Retired | 66 | 3ª |

| 5 | Marketing / Sales Dept. Galicia, Castilla y León, Aragón y Catalonia | 52 | 4ª |

| 6 | Technical Department / Sales La Rioja, La Mancha, Extremadura, Mallorca, C. Valenciana and Andalusia | 48 | 4ª |

| 7 | La Mancha Sales Dept. | 49 | 4ª |

| 8 | Production Dept. | 52 | 4ª |

| 9 | Sales Dept. La Rioja, Navarra and the Basque Country | 38 | 4ª |

| 10 | Production Dept. | 46 | 4ª |

4. Results

The findings obtained from the study are presented in this section, following the development and application of the research techniques. Initially, the results obtained from the thematic analysis are analysed, followed by those obtained from the critical incident technique CIT.

In the subsequent part, the outcomes of the thematic analysis are presented. Three main analytical categories are revealed, as seen in Tables 2, 3, and 4. The first thing to observe on the right-hand side of the tables are the three primary categories, referred to as “analytical categories”, which have been examined in the Viveros Villanueva Vides company: Innovation, SEW, and EO.

Regarding innovation, the analysis of the interviews indicates that this manifests in three distinct ways depending on the scope of the company affected by the improvement carried out. Consequently, the development of innovation within the organization occurs in three ways: product, process, and people.

The application of the five categories of the emotional component of business families to Viveros Villanueva Vides has revealed that family control and influence is a prominent feature in the company. It is noteworthy that the family has complete control over the business as the ownership of the property is equally distributed among the five partners, who are all brothers. The board of directors comprises the children of these partners, ensuring that everyone has a say in the decision-making process. This results in a united front when it comes to approving initiatives such as research and development projects.

Regarding the second, it should be said that all participants feel they identify with the company. Moreover, so high is this sense of identity, that even in-laws, not direct family members, feel as if they too are children of the family. As Informant 5 says:

I am the son-in-law of one of the partners, as I married his daughter, and 25 years ago I was presented with the possibility of joining the family business and I decided to do so, and although I am not a son, I feel very identified because this company belongs to the whole family and each member of the family leaves his or her mark, right? And I feel identified because I have also left my mark.

Table 2: Thematic coding process of Innovation

| Participants’ quotes | Potential categories | Analytical categories |

|---|---|---|

| “The biggest change was that, the introduction of the grafted plant, which is now 99% of what is done this way and, in my time, initially, it was the opposite, 90% were grafted. | Product innovation | Innovation |

| We have been improving as much as possible, incorporating machinery, carrying out research projects to improve plant health...” (Inf. 9). | Process innovation | |

| “When we started 40 years ago and more, we did everything with the hoe and that could no longer be, the times brought tractors and we started using them” (Inf. 2). | ||

| “You try to improve also to make the jobs easier for the workers themselves by incorporating more comfortable ways of working.” (Inf. 7) | People innovation |

Table 3: Thematic coding process SEW

| Participants’ fees | Potential category | Analytical category |

|---|---|---|

| “My father was the owner initially and little by little the sons came along, so now the ownership of the company is distributed among the five brothers and sisters who we own the company. (Inf. 2) | Family control and influence | SEW factors |

| “We now have a board of directors and we meet every Friday at the end of the month”. (Inf. 6) | ||

| “Yes, I identify 100% with this company” (Inf. 2) | Identification | |

| “I’m a son-in-law, but I wanted to be introduced here as a son”. (Inf. 10) | ||

| “It is essential to be attentive to everything around you, you are not alone, in the end you need more people and even companies. From your own sector that are competitors but that at a certain moment you can collaborate with them and help and teach each other”. (Inf. 1) | Binding social ties | |

| “With the workers it is very important to have a clear working relationship and the best possible personal relationship, if you don’t manage to have a team that is calm, that is at ease, it doesn’t work”. (Inf. 9) | ||

| “It is something that has allowed the whole family to live, to make a good living, so it is a feeling of gratitude and that it will be there until I die, because I will be a nurseryman even though I no longer work in it because I have made it my own. (Inf. 3) | Emotional attachment of family members | |

| “It is a feeling of pride, a lot of responsibility, you don’t want what your great-grandfather founded to end tomorrow. (Inf. 8) | ||

| “I would give my life for the young people to stay with her, they are very well prepared and very effective”. (Inf. 2) | Renewal for family ties | |

| “Of course, that would be a very nice thing to do, just as it has been done in the past”. (Inf. 10) |

In terms of binding social ties, at Viveros Villanueva Vides workers, customers, and other companies in the sector have played a significant role with the company, with some collaborating on innovation project, as Informant 6 says:

All the research and development projects we have done have been in collaboration with research centers. Then we have also collaborated with clients, as in the first one we did, which was with a winery, and in some we have also collaborated with other groups.

Regarding the emotional attachment of family members, the feeling of pride and ownership they share for the company stands out, which can be seen in sentences such as the following: “Feelings... I don’t know how to explain. Everything, I feel everything, in the end it is a whole life that we brothers have formed following our father, then the nephews, and if the next ones come, then we will see!” (Informant 4). The reason for these feelings among the interviewees is that working in this company has become a way of life for them, for which they are grateful to their predecessors. In relation to the last category, the renewal of family ties through dynastic succession is already demonstrated by the fact that in this study we have been able to analyse the third and fourth generations who have continued with the family business. In addition, family members express the desire for the company to continue in this way.

Finally, the EO was perceived in the company from its beginnings. Proof of this is the proactivity and autonomy that the family members themselves have developed. The parents have been teaching and showing the operation of the business to their children in such a contagious way that they themselves have decided to stay in the same line and enter into the search to continue the enrichment/success of the company, “Well, it was something you knew because you went with your father, who was already teaching you something, and then in my case I decided to study as a agricultural technician and I was focused on coming here because I liked the area”, says Informant 10.

Table 4: Thematic coding process EO

| Participants’ fees | Potential category | Analytical category |

|---|---|---|

| “Of course, that would be a very nice thing to do, just as it has been done in the past. (Inf. 10) | Proactivity | Entrepreneurial orientation EO |

| “We went to help my father and we worked without knowing many things because in the field it is all experience, like in everything else, and with the children and nephews they all started when they were between ten and twelve years old, after school they came to the field to help us and when they were very young, they started everything and now they are the ones who run the business because they know everything since they were ten years old”. (Inf. 2) | ||

| “Being involved on a day-to-day basis, trying to do things in the best way with the most feeling and care for something that is yours, that you want to do it in the best way and that you have to move forward and not fall behind”. (Inf. 10) | ||

| “It seems to me that one of the great virtues here is that little by little each of the children or nephews and nieces have been acquiring the responsibilities that our parents had. The father was giving him that responsibility and little by little he was stepping aside and we were pushing until now the third generation has disappeared and we are the fourth generation” (Inf. 8). | Autonomy | |

| “A lot of work and then also the capacity that the grandfather initially had to see the possibility of trading, to look outside, to have the first telephone, to buy one of the first cars in the village, a tractor... That was a little bit the key to grow and improve”. (Inf. 1) | Risk-taking |

A crucial factor that makes this possible is the decision of the members to take risks, as they have never stopped taking on new challenges and striving to keep the company prospering. Consequently, it has succeeded in surviving over time.

Later, in the discussion section, we will see that the three analytical categories are not isolated but interrelated with each other and converge to maintain the innovation processes in the company.

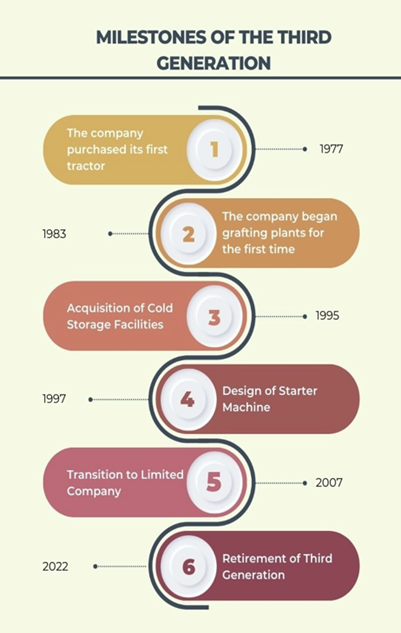

The presentation of the company’s key milestones through a review of critical incidents is as follows: a total of 26 milestones have been identified. The first six correspond to the third generation, who, despite starting with a more basic job and limited resources, were able to adapt and grow with the knowledge and resources available to them at the time (see Figure 1).

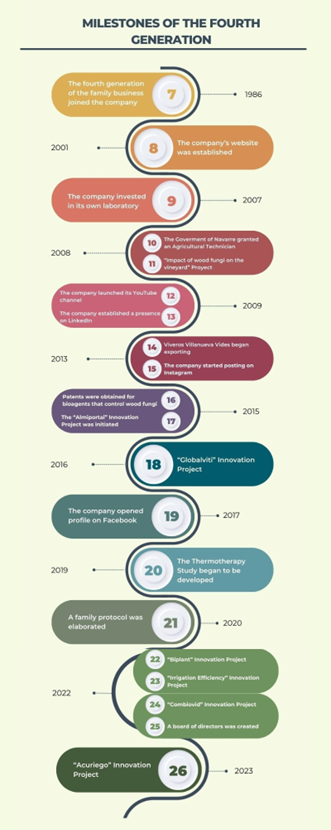

From milestones 7 to 26, it is seen that the fourth generation will soon enter the family business and with-it new ways of working and progressing the company (see Figure 2).

The Viveros Villanueva Vides case study exemplifies the collaboration between EO and SEW in fostering innovation within a family-owned business. The relationship between EO and SEW is symbiotic, where EO acts as a driving force that positively influences SEW and vice versa. This dynamic relationship facilitates innovation within family businesses, ensuring an optimal interaction between these two elements. The effective transmission of EO across generations is crucial for the preservation of SEW, as it is deeply embedded in the culture and identity of the company. This combination of experience and an innovative spirit, fostered by EO, is essential for the evolution and adaptation of the family business over time. Moreover, the positive relationship between EO and SEW significantly enhances the innovation processes, highlighting the necessity for all members of the organization to possess the capability to seize business opportunities and develop competitive advantages through innovation.

Informant 8 says, “One learns from their parents and gradually implements better practices in the field.” It is essential to foster entrepreneurship in new generations and their ability to innovate and adapt to changing markets to ensure the survival and continued success of family businesses. The relation between EO and SEW emphasizes the importance of this ability for all members of the organization, to seize business opportunities and establish competitive advantages through innovation, as emphasized by informant 2: “If you don’t innovate, you’ll fall behind and stay stagnant.”

5. Discussion

The case study of Viveros Villanueva Vides, a renowned Spanish family enterprise operating in the wine and agricultural sectors, serves an exemplary instance of a family business using EO and SEW successfully. This firm is actively involved in innovation and biotechnology initiatives, which has led to its recognition as one of the most innovative family businesses in the region and is a perfect case to demonstrate how EO and SEW foster innovation in family firms. In addition, it puts paid to the idea/it contradicts /it challenges the idea that family firms have a limited scope and invest less in research and development than non-family firms (Block, 2012; Chrisman & Patel, 2012; Classen et al., 2012). However, family-owned businesses, contrary to popular belief, may encounter obstacles in innovation due to the influence of emotions on management decisions. In the case of Villanueva, Informant 2 of the third generation highlights this view by stating, “Innovation is crucial; without it, we will not progress.” Additionally, Informants 8 and 9 of the fourth generation emphasize the significance of innovation in maintaining competitiveness in the industry by stating, “It is essential to innovate and improve processes and products.”

In more depth, this study reflects that the transmission of EO across generations has played a significant role in fostering a proactive approach to work and a commitment to continuous improvement among all members of a company. This highlights the importance of adopting an entrepreneurial mindset beyond the founder. To ensure long-term viability, it is essential for all employees to exhibit entrepreneurial behaviour. Over time and with multiple generations involved, companies can capitalize on their accumulated experience and tacit knowledge to drive innovation (Sirmon et al., 2007; Sirmon & Hitt, 2003; Alonso & Leiva, 2019). When the next generation takes over, they have already initiated innovative projects within the company, such as the development of a start-up machine (milestone 4) and, later, the establishment of their own laboratory (milestone 9), which enables them to conduct research within the same organization. Moreover, one of their initial tasks was to obtain patents (milestone 16), which gave them a competitive advantage, as Villanueva discovered a new technique that was not known to/used by other companies that was not available to other companies.

Thus, this study demonstrates that EO is facilitated by emotional involvement, a shared life history, and the use of a private language, which enhances communication among family members (Tagiuri & Davis, 1996). This leads to more effective knowledge sharing compared to non-family firms (Chirico & Salvato, 2008). The autonomy of the entrepreneurially orientated family enables the organization to generate sustainable competitive advantages (Cabrera-Suárez et al., 2014), adapt its capabilities to changes in the environment, and create value over time (Helfat & Peteraf, 2015; Teece, 2007; Zollo & Winter, 2002). With regard to this, Informant 11 underlines the need for innovation by stating, “Innovation is necessary for a company to remain relevant and competitive.”

The transfer of entrepreneurial values and practices encourages new generations to embrace risk-taking, seek opportunities, and be adaptable, thereby ensuring the long-term survival and success of the family business in a competitive environment (Habbershon et al., 2010). This transmission is crucial for maintaining the innovative orientation and adaptability of the family business, which is also enhanced by the preservation of SEW (Hernández-Perlines et al., 2020). The Villanueva case makes innovative efforts in biotechnology, and its international market expansion demonstrates the crucial role of EO in driving growth and adaptation across generations, supported by SEW’s foundational values.

The above supports the notion that families who prioritize the preservation of their shared SEW tend to generate a significant number of innovations in various aspects. In our case, the presence of SEW is evident in all dimensions and across all generations, and the company has been entirely controlled by the family since its establishment. This family involvement in management and decision-making has led to a better understanding and identification of the challenges and opportunities facing the firm, which, in turn, can encourage innovative behaviour (Zahra, 2005). The sense of belonging that comes from being part of a family-owned business translates to maximum family involvement in the company and its projects, which, in turn, influences other employees and managers (De Clercq & Belausteguigoitia, 2015). Emotional aspects, such as the values and feelings that family members have towards the company, are transmitted between generations.

The findings of this study reveal that family firms can adapt to changing market conditions and satisfying evolving customer needs, thereby opening up new market opportunities (Brown & Teisberg, 2003). Furthermore, the study challenges prior assumptions made by certain authors, such as Roessl (2005) , Alberti et al. (2014) , and Lazzarotti et al. (2017) , who claimed that family firms have limited external collaborations and are less likely to participate in cooperative R&D projects due to their conservative nature. Contrarily, the research indicates that these firms foster strong social ties, which are often facilitated by the previous generation. This is exemplified by the testimony of Informant 8: “I already told you that the first project we did was with a winery where his grandfather already worked with our grandfather, the father with our father and the third generation of his with us.” This exemplifies the distinct nature of family firms, not only within themselves, but also in their interactions with others.

Thus, the relationship between EO and SEW in family businesses is intricate and has significant implications for innovation. The interplay between EO and SEW is characterized by a symbiotic relationship where each influence and enhances the other. EO drives the positive influence of SEW by fostering a culture of innovation, adaptability, and opportunity-seeking within the family business. This EO ensures the preservation and enhancement of SEW by securing the family’s legacy and identity through successful business practices and innovations. Conversely, the desire to protect and grow SEW motivates family businesses to adopt an EO, as innovative practices and growth are seen as means to sustain the family’s influence and legacy over time. The relationship between EO and SEW in family businesses fosters a culture of innovation that is crucial for the long-term success and competitiveness of these firms.

6. Conclusions

Research on the transmission of EO and its relationship with innovation in family businesses has been limited in recent years, but several studies and experts concur that this aspect is crucial for the success and survival of family businesses (Casillas et al., 2011). The transfer of EO from one generation to the next is vital for the long-term endurance of the family business, as this mindset is deeply ingrained in the company’s culture and identity (Dessì et al., 2023; Giner & Ruiz, 2022). The blend of experience with an EO is considered indispensable for the evolution and adaptation of the family business over time (Chirico et al., 2011; Zellweger et al., 2012), as indicated by Informant 9: “Success arises from being actively involved on a daily basis for many years, striving to perform tasks to the best of one’s ability and with a sense of ownership. Progress must be made, and one must not fall behind.”

SEW is indispensable to maintaining EO and innovation in family businesses across generations (Alonso-Dos-Santos & Llanos-Contreras, 2019; Schepers et al., 2014), as evidenced by the experiences of parents and children, and noted by Informant 8: “One learns from their parents and gradually implements better practices in the field.” To ensure the survival and continued success of family businesses, fostering entrepreneurship in new generations and their ability to innovate and adapt to changing markets is essential (De Massis et al., 2016; Kellermanns & Eddleston, 2006). The positive influence between EO and SEW highlights the importance of this ability for all members of the organization, in order to seize business opportunities and establish competitive advantages through innovation, as emphasized by Informant 2: “If you don’t innovate, you’ll fall behind and stay stagnant.”

Therefore, EO serves as the driving force behind the reciprocal positive impact between the SEW and vice versa, fostering innovation and ensuring an optimal relationship between them within the family business.

6.1. Practical Implications

The importance of studying EO, family business, and innovation in a qualitative way lies in the complexity of obtaining this information through secondary data. Therefore, in-depth studies are required to properly understand these phenomena. Qualitative studies allow us to explore the underlying perceptions, experiences, and dynamics that are not easily captured by quantitative approaches, making them critical to gaining a holistic and detailed understanding of these issues. Qualitative studies are also essential for analysing aspects such as the transmission of values, passion for the company, and the preservation of the family legacy, which are often intrinsic to the family business and cannot be fully captured through quantitative data.

Secondly, the study highlights the role of strong social ties and external collaborations in driving innovation. Family firms are encouraged to cultivate relationships with external partners, which can lead to the creation of knowledge networks and the sharing of breakthroughs, thereby enhancing their innovation processes, as has happened in our case, according to Informant 6:

All these projects are always generated in a group, the individual alone will never do anything. You need a good relationship with clients, with other organizations, because by bringing together the knowledge of all parties you will make a project emerge and be born.

This challenges previous assumptions about family firms’ reluctance to engage in cooperative R&D projects and underscores the value of external collaborations.

Moreover, the findings suggest that family businesses can benefit from leveraging their unique family values and history to foster a culture of innovation. By effectively harnessing and conveying these distinctive values to all members of the organization, family firms can enhance corporate performance and output. This involves establishing and sustaining positive relationships with employees, customers, and other industry players, which are crucial for optimal innovation processes.

Lastly, the case study demonstrates that the intergenerational transmission of EO contributes to the development of innovation processes and the attainment of better outcomes within family firms. This indicates that fostering EO in new generations is vital for the innovation and preservation of SEW in family firms across generations. Family businesses should, therefore, focus on cultivating attitudes towards risk-taking, opportunity seeking, and adaptability among their members to remain competitive and relevant in their respective industries.

6.2. Limitations

The study, while providing valuable insights into the interaction between EO and SEW in fostering innovation within family businesses, has several limitations. One notable limitation is its reliance on qualitative methodology and the use of a single case study, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. As Martínez (2006) and Yin (1994) suggest, while the case study of “Viveros Villanueva Vides” delves deeply into the dynamics of one family business, the specific context and characteristics of this business mean that the findings may not be directly applicable to all family firms. The study’s design, focusing on a single business family’s interaction, provides a rich, detailed account of that family’s experience but may not capture the full range of experiences and strategies employed by other family businesses in different contexts or industries.

These factors may affect the generalizability and objectivity of the findings, suggesting that further research, possibly incorporating quantitative methods or multiple case studies, is needed to validate and extend the results.

6.3. Future Research

Future research should consider exploring the variability of EO across different types of family firms, examining how factors such as industry, firm size, and generational stage affect the manifestation and impact of EO on innovation and SEW preservation. Given the foundational role of EO in shaping long-term performance and transgenerational entrepreneurship, it would be beneficial to investigate how different dimensions of EO contribute to these outcomes in varied contexts.

Additionally, expanding the scope of research to include multiple case studies across different geographical regions and industries could enhance the generalizability of findings related to the interaction between EO, SEW, and innovation. This approach would allow for a more nuanced understanding of how cultural, economic, and regulatory environments influence the entrepreneurial and innovative activities of family firms.

Quantitative studies that employ longitudinal data could also provide insights into the evolution of EO and its impact on firm performance and innovation over time. Such studies could help to clarify the causal relationships between EO, SEW, and innovation, contributing to a deeper understanding of the mechanisms through which EO fosters innovation within family firms.

Finally, future research could explore the role of external collaborations and social ties in enhancing the innovative capabilities of family firms. Investigating how family firms cultivate and leverage these relationships to support their innovation efforts could offer valuable insights into strategies for overcoming the challenges associated with family-specific attributes, such as conservatism.