Introduction

Chile is renowned for its trade openness and high economic integration to the world, as well for its substantial reliance on cooper and other natural resources exports. This has been a key issue for different governments, for which they had established various strategies and policies to transform the export and productive matrices into services, based on the concept that services could be a way to reach higher development stages. The importance of the service sector in economic development has increased in the last decades, with a progressive strengthening of its weight in economic activity and employment. The increasing markets integration and emergence of new tradable services, as a result of technological changes and new forms of production, have led countries to identify more complex services as a way to develop and diversify their productive and export baskets.

There is consensus that the diversification of the export basket, especially oriented to qualified services, is essential to reach the goals of national development, and to achieve the consequent improvement in the living conditions that such development would enable. In this sense, the role of the State through the implementation of economic development strategies is fundamental and has been so in countries that has reached higher development levels. Despite of the above, in Chile, the results obtained account for an insufficiency of the public policies implemented. Exports of services have grown but not in the expected and necessary amount to modify the Chilean situation. The composition of Chilean exports remains anchored on the exploitation of natural resources with low added value. Democratic administrations reaffirmed the openness strategy, but aimed at reorienting it towards an improvement in the quality of exports. Was not until the first government of President Bachelet (2006-2010) when the need for industrial policies was recognized as a way to improve the productive and export structures to achieve development.

The objective of this article is to capture the perception of key actors regarding the results of the different attempts to increase services exports and create a solid new export sector in Chile, in order to understand the tension between the manifested intention of diversifying the economy and the persistence of an export basket primarily based. It explores the perception on an overall strategy to boost the service sector within the country, with no particular emphasis on specific sectors or modes of supply. For this article, together with the literature reviewed, a series of interviews were conducted to identify the discussions about the convenience of the State intervention for economic development or, on the contrary, its limitations; in other words, the arguments that defend or refuse to have a State that acts prioritizing or promoting the export of services. The interviews were conducted to key informants from public, academic and private sectors, including international organizations and NGOs. The paper is organized as follows. In the first section the relevant literature that sustains the positive relation between trade in services and development is reviewed. In the second, an overview of the different programs implemented in Chile will be mentioned. The third section presents the results of the interviews. Finally some conclusions and policy recommendations are drawn.

Trade in services and development

The casual relationship between trade in services and development is still difficult to probe. The absence of a strong theoretical corpus is compensated with a high degree of agreement and empirical evidence that some services exports boost growth, which is a precondition for development (Adlung, 2007; Mattoo, Rathindran & Subramanian, 2006; UNCTAD, 2016; World Bank, 2010). Stylized facts support this positive relation; services export participation of developed countries is higher than those of developing countries. Countries have shown to be more resilient to crisis when they are services oriented. It is more common to find literature about the role of services as the backbone of an economy, and the role they have to overcome poverty (Hoekman & Mattoo, 2008; Riddle, 1986). Services are identified as the pillar of growth, while open services markets have become the underpinning for global growth (Kenneth, 2006; UNCTAD, 2016).

Despite its growing importance in economic activity, there is no common definition for services. Traditionally, services had been characterized by their intangibility, invisibility, and the need for producer-consumer simultaneous interaction, but the advances in information technologies had led to reconsider this description (López & Muñoz, 2016b). For the purpose of this article, and due to its wide use, the definition made for services in the framework of international trade negotiations, particularly in the GATS agreement, will be used.

For this work several experts from the public, private and academic sector, civil society and NGOs in Chile were interviewed to collect their perception on policies that promoted services exports, implemented in the period 1990-2014

Once thought of as mainly non-tradable and with low productivity potential, changes in production structures and technological advances have modified these perceptions. Trade in services has witnessed exponential growth in the last decades. Today, international services transactions include various activities such as transport, telecommunications, financial services, education, health care, and business oriented services.

Trade liberalization is a fundamental channel to improve services performance (Borchert, Gootiiz, Grover & Mattoo, 2015). According to WTO (2010), the benefits of trade liberalization could be divided in domestic and international dimensions. The first one is that liberalization improves the domestic services market, attracts investment, which enhances services, and increases competition, which theoretically improves innovation. Nevertheless, these results depend on how liberalization is executed. The international dimension states that having a better domestic services market increases the probability of export services and manufactures. Robinson, Wang, and Martin (2002) considered that service sector trade liberalization not only directly affects world service production and trade, but also have significant implications for other sectors. Konan and Maskus (2006) determine that services liberalization increases economic activity in all sectors, raises the real returns of capital and labor, and generates large welfare gains.

Literature also deals with the effect of openness in services on economic growth for countries at different stages of economic development (Bhagwati, 1984; Borchert et al., 2015; Wölfl, 2005). Francois and Reinert (1996) point out that value added originating in services is positively linked to the level of per capita income. Regarding developing countries, Cattaneo (2010), in an individual analysis for different sectors, found the positive effect between trade in services and development. El Khoury and Savvides (2006) measure the influence of services liberalization in developing countries and found a relationship between openness in telecommunication services and growth for countries with low per-capita income.

Deardorff (2001) points out that trade liberalization in services can yield benefits, by facilitating trade in goods that are larger than one might expect from analysis of the services trade alone, and can also stimulate fragmentation of production of both goods and services. Arnold, Javorcik and Mattoo (2006) conclude that services matter for manufacturing performance and that there is a strong correlation between services sector reform and productivity of local producers relying on services as intermediate inputs. Deardorff and Stern (2008) explained that opening services sectors to foreign providers is a fundamental channel through which affect downstream productivity in manufacturing.

The positive effect of services in labor force is another relevant route of research (Bhagwati, 1984; Francois & Reinert, 1996; Hansda, 2001; Riddle, 1986). Services is one of the most important labor force origin and will be each day more relevantly in the global value chains (Miroudot & Shepherd, 2016; UNCTAD, 2016).

Trade in services and its liberalization have a positive relation depending on how the implementation of opening markets is performed; also the benefits are in direct association with the level of development of each country. Trade openness improves the domestic services sectors and its possibilities of increasing exports. Trade in services, particularly telecommunications and transport, is a key issue in global value chain structures and adding value to exports, which are the real challenges for Latin America, with highly concentrated export baskets.

Policies and institutions, and their interaction, may explain some aspects of the dissimilarities in countries’ services sector performance. There is an increasing literature analyzing the role of export promotion policies and services trade development (Cali, Ellis & Williem, 2008; World Bank, 2010). There is high agreement that some kind of promotion policies are needed to boost or create a services export sector. Without an active promotion in these sectors, exports tend to be concentrated in a few firms, and in products with less dynamic demand. A central idea is that export promotion policies require not just liberalization or macroeconomic stability, they should be directed to help exporters to overcome the sectorial barriers and to have a fast reaction to prices or other markets signals. The capacity to export services is determined by the interplay of endowments, institutions and infrastructure.

Regarding trade in services, a series of arguments could be acknowledged to justify the State interventions, besides those identified for goods. Firstly, owing to the nature of services, they are characterized by elements of natural monopoly, high barriers to entry and asymmetries of information. Secondly, they are not subject to easily identified tariffs, but regulations, norms and laws form other States. Thirdly, the higher complexity in selling intangibles also implies more difficulties for exporters in getting to other markets. The multimodality of services transactions creates different and more barriers to trade.

A strategy in services demands to link institutions and instruments with the design of scenarios in a short and a long term that allow creating competitive advantages, instead of using the existing ones (Cali et al., 2008). These policies should: i) create and enable competition between market players; ii) guarantee the quality of the services provided; iii) protect consumers and guarantee transparency; iv) protect the environment; and v) ensure access to services. Barriers to services exports that governments must overcome include: a) services are not goods, many times the problem is that policy makers just try to replicate these strategies in services (Francois & Hoekman, 2010); b) the absence of an internation al agreed definition and of trustable statistics do not help policies design (López & Muñoz, 2016a); c) the unknown aspect of barriers, more difficult to identify such as regulations, norms, etc. (Hoekman & Mattoo, 2008); d) identify those sectors with export potential. Finally, the dynamic changing nature of the sector and its necessities are more complex than they were ten years ago.

Chilean strategies for services export promotion

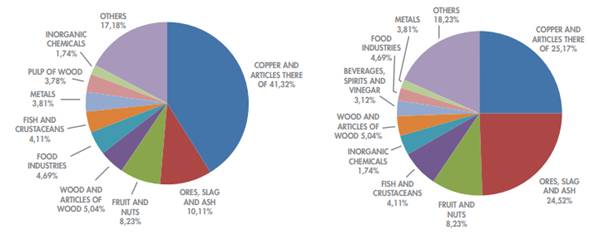

One of the main economic challenges Chile has identified, is to diversify its concentrated export matrix. As shown on Graph 1, commodities, particularly cooper mining, has been the main export product for decades. While in the early 1990’s cooper and ores (from cooper) represented 51% of Chilean exports, for 2016 it remained almost unchanged with an involvement of 49%. Although some new industries have developed, such as winery or salmon, the productive base anchored in mineral exploitation remains the main income source.

Is in this context, services have been identified, by Chilean authorities, as a possible way to diversify and expand the productive and export matrixes. The continuous expansion of world trade in services (Graph 2), as well as the increase productivity observed in this sector within the country (Aroca & Garrido, 2017), are amongst the factors that explain the reasons why services are perceived as an alternative for the Chilean economy.

One of the main problems regarding diversification is the unsolved discussion between selectivity and neutrality of economic policy. On an institutional basis, trade in services promotion has been based mainly in two Ministries: Foreign Affairs and Economy. At Foreign Affairs, DIRECON (Dirección General de Relaciones Económicas Internacionales) is responsible for international economic relations and trade negotiation; and ProChile, for export promotion. At Economy, CORFO (Corporación de Fomento de la Producción) has a series of programs aimed to boost domestic firms’ economic capabilities. In the last years, other institutions have also started to get involved in facilitate trade in services. Particularly at the Treasury Ministry, the customs service (SNA), internal revenue service (SII) and foreign investment attraction office have begun to get awareness of the importance of services exports. Below we present the main policies implemented in Chile towards services promotion in the last years.

Trade liberalization

In the context of a neutral economic policy, trade openness becomes a sort of base for economic policy. Governments worked to set up the conditions for the development of all industries, allowing them to compete both at the domestic and international markets. As a small economy, opening and guaranteeing access to new markets become the main economic objective. Services become part of these strategies, particularly after their inclusion in the Uruguay Round, and the establishment of the WTO General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) in 1995. As this was the first negotiation regarding services, Chilean comitments are less than their actual openness. The main advances in services negotiations have been done through preferential agreements, where the inclusion of services becomes an important condition for Chile. In general, service chapters contain commitments in three of the four modes of provision, as mode 3 is confined to specific foreign investment chapters or bilateral agreements. Out of the 26 Chile’s trade agreements currently in force, 18 contain provisions related to trade in services.

In order to complement the market’s access to trade agreements, Chile has also signed Investment Promotion and Protection Agreements to attract FDI, by securing conditions and delivering legal certainty to freeing investors; and Double Taxation Agreements, with the aim of facilitating the establishment of companies in the country and allowing national firms to set up branches and representations in third countries.

Sectorial Brands

This program was originated with the objective of supporting the Chilean productive sectors through the international positioning of “sectorial brands”, representatives of national productive sectors and that contribute to the image of Chile abroad. The incorporation of sectorial brands into ProChile since 2011, has made possible to order and strengthen Stare support for the internationalization of companies and productive sectors, by taking advantage of the institution’s experience in promotional matters of exports, knowledge of the markets and its wide international network. This program is planned for one year and must be renewed annually. ProChile undertakes to co-finance up to 60% of annual activities with no ceiling. Since the inception of the program, 19 sectorial brands have been created, based on both goods and services. The sectorial brands focused on services, included gastronomic, architecture, biotechnology, education, cinema, engineering, information technology, mining suppliers and tourism.

Global services cluster

In 2006, at the beginning of Bachelet’s presidential term, the National Innovation Council for Competitiveness defined the National Innovation Strategy for Competitiveness. In the framework of this strategy, and based on the diagnosis made by the Boston Consulting Group’s "Cluster Competitiveness Study of the Chilean Economy” in 2007, five clusters were defined by the sectors with the greatest potential for growth in the medium and long term: food, mining, special interest tourism, aquaculture and offshoring. During 2011, under the administration of President Piñera, CORFO defined non-selectivity as a management criterion, and reformulates the cluster program, in order to support private sector initiatives in a neutral way.

Besides the clusters policy, CORFO has different programs, not only oriented to services, but mainly directed to overcome financial problems, and the development of new industrial areas. Amongst its programs, which can be used by services providers, we may acknowledge programs on competitive creation, technological innovation, business and validation, entrepreneurship, and investment and finance. Additionally, some tax exceptions for services had been implemented, such as VAT exemption for those services supplied by foreigners not living in Chile that Customs classifies as services exports, and to those received by tourism hotels in foreign coin.

Key stakeholders perceptions

Methodology

For this study, we employed a qualitative methodological approach, in order to gain an in-depth understanding on why development-oriented policies did not achieve the expected results, through the identification of the reasons perceived by key stakeholders related to services and promotion policies. To identify these agents, we followed a two-step approach. First, we identified the main organizations; second, amongst those, we identify who hold key positions during the examined period, forming a preliminary list of stakeholders to be interviewed. Semi-structured interviews were conducted between May 2014 and March 2016. They were informed that their contribution was voluntary, their identities would be kept confidential, the results were going to be publish anonymously, and interviews would last around 60 minutes. The participants must give their informed consent before the interview began. Interviews were conducted by two researchers, and were recorded with the participants’ permission. All data were de-identified, and sector specific codes assigned for publications purposes. Table 1 presents a summary of the sample.

Table 1 Sample demographics (n = 49)

| Demographics | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Sector | - | - |

| Public | 24 | 49% |

| High-level officials | 11 | 22.4% |

| Mid-level officials | 13 | 26.5% |

| Private | 11 | 22.4% |

| Chambers | 6 | 12.2% |

| Companies | 5 | 10.2% |

| Academia / International Organizations | 12 | 28.6% |

Fuente: Elaboración propia

Regarding the public sector, high-level officials include ministers in different governments (Foreign Affairs, Treasury, Economy and Agriculture), vice-presidents of CORFO, and directors of DIRECON and ProChile. In the results section, their opinions have been identified as A1. Mid-level officials include directors or department responsible from DIRECON, CORFO, other ministries and agencies, and have been identified as A2. Regarding the private sector, we have split our sample into two categories: stakeholders from individual firms (B1), and actors belonging to business chambers and private associations (B2). Finally, stakeholders from the academy, NGOs and international organizations were identified as C.

The sample has a bias towards the public sector, mainly towards the ministries of Foreign Affairs, Economy and Treasury. This may be explained by the accessibility to stakeholders available to answer our questions and why more aggressive strategies were not designed, used or considered from different administrations, since there was a deep awareness that the lack of complexity in the country’s export and production baskets was insufficient to achieve better jobs, greater equity and improve individuals’ life quality. Nevertheless, little discrepancy was found amongst interviewees, particularly when classified according to their sector. With the information gathered, we concluded that we has arrived to data saturation point, as no new evidence was added by the last interviewees, and the depth of the gathered information probed to be sufficient to answer our research question.

Results

For a better understanding of the results, three overlapping levels were distinguished, in a logical hierarchy from greater to lesser extent:

Level I: Considerations on economic doctrines and corporate cultures.

Level II: Considerations on the specificity of service industry and economic considerations.

Level III: Considerations on specific policies and instruments.

Level I: Economic doctrines and corporate cultures

On this level, first order determinants have been grouped, namely economic doctrines adopted in Chile and its business groups. In all the interviews, these first order elements present an important explanatory load.

The consensus was that there has been an absence of policies that could, significantly, modify the Chilean export structure into services. At least until the first Bachelet administration, there were only punctual initiatives to promote services. Interviewees indicated that the latter is a consequence of the neoliberal model’s high permeation into Chilean society. “The State subsidiarity (non-State intervention in economic aspects) was very clear, and it was fundamental to sustain it for the correct operation of the market” (A1). The model generated an institutional and thinking structure that defined the policy making towards productive development. “The model penetrated so much that it convinced policymakers that neutrality was best. It not only generated a political class, but companies also preferred this scheme of neutrality” (B2). There was a high agreement amongst interviewees that neutrality was the approach that defined the State approximation to the productive sphere, the absence of strategy was indeed the strategy: “there was no national productive strategy, much less to look at services in a formal way” (C).

Thus, the model becomes a kind of internal law due, in large part, to the desire for peace and governance present at a particular moment in recent history: democratic transition. Interviewee mentioned that “the rest of the region had emerged from dictatorships with severe problems of hyperinflation and economic disorder. We had to demonstrate that we were capable of giving governance without a military government in command” (C); “we were attached to the neoliberal model, because we had to ensure governance, and for that, every economic strategy should be international” (A1).

The other problem with the model is that, by removing any type of planning attempt and leaving everything to market forces, a problem emerges: a short-term vision in the government’s action. As one of the stakeholders mentioned “the general view of the region is short-term. This was radicalized before the neoliberal model and is notorious, for example, in the change that Chile did, modifying the presidential periods to four years.

The Government must create strategies and intervene. The debate is whether this should be done with vertical promotion policies or not. If the State does not choose winners, sectors would not develop

This makes impossible to achieve processes of greater magnitude" (A2).

The second first order determinant refers to business community, entitled in this context to assume the complex initiative of organizing the production processes of exportable services. There is a conception that Chilean business class did not have the necessary characteristics to assume such responsibility. The existing entrepreneurial culture is restricted, for reasons of cultural and historical class formation, in rentier forms; they aresmall elites, isolated and used to agree amongst them. In the case of the rentier element, “it would respond to the presence of factors associated with a society that lives off the exploitation of its natural resources and does not develop capitalism” (C).

The development of an export services sector requires highly trained entrepreneurs in the logic of complex management of productive advantages, not necessarily associated with natural factors. Some views that defended the model, argued that “entrepreneurs are called rentiers only because they like to earn money. And if they do it by exploiting natural resources and nobody regulates or prohibits them, why should they make efforts in another direction?” (A1). In addition, they pointed out that “they are more committed towards work, because they do not profit from the State. Look what happened with import substitution model” (A1).

Level II: Specificity of service industry and economic considerations

In this level, we have identified factors associated with the specificity of services sector, their conditions and how these are exacerbated due to some Chilean characteristics. Specifically, economic considerations are analyzed as a result of the implementation of the economic model.

The decision makers demonstrated unfamiliarity with services; this could be explained as a consequence of the following aspects:

the recent irruption of the services in the commercial world and later in the region. For example, ProChile just created a service department in 2004, established with “a low budget and at the request of a small group, and due to the requirement of international commitments” (A2);

services coexistence in a structured world for goods. “Policies have always been designed for goods and copied for services” (A1). This come about in most areas, where "excessive orientation to goods, as a result of the large endowments with which Chile has historically counted, has tarnished the development of services" (B1); and,

the difficulty of measuring them and the meager efforts made in this direction. In a model whose logic of operation and design of public policies is based on indicators such as efficiency andaccounting results, it is hard to incorporate a sector that has not been statistically weighted.

The interviewees reflected other problems in promoting services. Regarding taxes, particular interest has been put to SNA and SII. Interviewees argued that “there are problems at customs that are not their responsibility to solve, but of Treasury. The interests of the SII prevail before the SNA and, as there is not enough lobby, they are allowed to protect certain attributes” (B2). When consulted, authorities on this subject responded that these dependencies only operate within the framework of a law and, in addition, do not have sufficient resources to train and inform their operators or users: “we cannot facilitate more than we have done. The law allows us to only make the tax exemption on mode 2” (A2). The pre-eminence of services export taxes was highlighted as more important than the ones for goods. In some cases, double taxation agreements were reached, but they have not been sufficient. In other cases, users do not know their scope or existence, and there seems to be no incentive to disseminate these agreements.

The exchange rate was identified as a very relevant factor but it doesn’t get enough attention. There is little awareness that the exchange rate reduces competitiveness: "there is a kind of obsession for inflation and excessive Central Bank’s power in it. It has had strong consequences on the composition of the export basket and, as long as this is not understood, it is impossible to think of a change" (C). The model was very severe in establishing that the exchange rate should not be transformed into a productive policy, but clearly it is an instrument that has devastated the export basket and its composition: “moreover, if we review its evolution, is has not secceeded in heping non-traditional exports emergence. For services competitiveness is essential to address this issue” (C).

The process of Chile’s trade insertion in the world and its prominent role as part of the economic policy strategy could not modify, by itself, the export basket, as it was expected. Treaties rarely appeared in the interviewees’ opinion as an aspect to be addressed, although most FTAs subscribed by Chile have some reference to services, although in no case were identified as a useful exporting instrument. However, overvaluing trade policy in a country’s economic policy may lead to neglecting the internal aspects of this insertion: “trade agreements have not had a sufficiently relevant effect, apart from the opening of markets and double taxation” (B2). Another negative aspect is that this conception has disqualified the design of other policies, because “the agreements served in many aspects, especially because they gave Chile a kind of international certification as a reliable country”.

Regarding other specific characteristics, human capital English proficiency is essential in the service export process: “we need skilled manpower and we do not speak English. There is a shortage of human capital. With better labor we could create new sectors” (A2). Public-private partnerships in Chile were not perceived to be developed, and although “there are some initiatives, they are small. There are not as successful as the one related to the salmon, for example” (C). It is possible to mention some experiences in the services sector, such as the case of architects, engineers, or even some timely export in areas of information technologies, but they do not have yet characteristics that allow them to be sustainable and successful.

Level III: Specific policies and instruments

At this level, policy considerations and specific instruments related to services are addressed. The interviewees pointed out that there were some initiatives for the design of programs towards the services sector development, but they emphasized that they clearly did not correspond to a project of greater complexity. In addition, “there is little money and there is an important dispersion of efforts” (A2). “There are few or no strategies in the modification of norms or regulations that will help to advance in the conversion. The speeches have not been translated into regulatory changes, and much less economic” (B2)

In all the interviews, ProChile and CORFO were referred as the entities most closely linked to diversification and service-oriented policies. Opinions were divergent, but they agreed in describing them as institutions with little functionality and with few resources, which support as much as possible, but not in a relevant manner. Furthermore, the multiplicity of institutions oriented to the promotion and support of services exports that do not have any kind of institutionalized coordination becomes an obstacle to the implementation of the support itself. “There is no link between ProChile and CORFO. It is more about a personal relationship than a process of coordination” (A1). They mentioned that there is something similar in the private sector, because “those who make policies do not coordinate, nor do we, the chambers, on more obvious issues” (B2), and there is an uneven or duplicate distribution of resources.

Finally, respondents were particularly asked about the reasons why the global service cluster did not function. As we mentioned, it meant a turning point in the policy of neutrality that emerged in the first administration of President Bachelet. In some cases, the stakeholders’ responses showed that the problem refers only to the suspension of funds directed to the program. However, they recognized that the structure of the policy allowed it to be dismantled easily: “it is necessary to think the policies in productive matters with a more long term perspective, since the effects are only long term” (A2). So it cannot be thought that, in a framework of four-year presidential periods, certain policies continue to be pursued, which also require significant amounts of resources. As one interviewee summarized, “with respect to the cluster initiative, they are long-term processes that should have been allowed to mature, as was trade policy” (C). There are more critical expressions, which consider that “the cluster failed because there was no clarity about what was wanted to propose. The cluster failed because what was raised to attract high technology actually attracted cheap labor rather than modern services” (A1), or that “the cluster failed because there was not enough long-term vision” (A1).

In order to wrap-up, Table 2 presents a systematization of the research findings, dividing into the three analytical and actors levels. Level I refers to the penetration of a neoliberal model with a conception of a subsidiary State embedded in all levels of society. It is a State that has limitedly promoted the service industry as a consequence of the predominance of ideologies or political philosophies that privilege minimal State intervention. On the other hand, it refers to the existence of an entrepreneurial class that hasn’t had the strength or will to modify productive and export patterns.

Regarding Level II, interviews revealed that the perception is that, in the short term, services are less profitable with respect to the development of alternatives such as agricultural or mining industry; in a country whose policy perspective is closely related to electoral periods, it is complex to think of implementing strategies whose results would be noticeable over longer periods; and there is a high ignorance of the service sector and its potentialities, particularly regarding those of greater complexity.

Finally, on Level III, the lack of understanding of services can be explained by the following reasons: the recent irruption of services in the commercial world, their coexistence in a world designed and structured for goods, and the methodological difficulty in measuring them. About ProChile and CORFO, the entities most closely linked to diversification and service-oriented policies, opinions were divergent, but they agreed that they are institutions with little functionality and with few resources, which support as much as possible, but not in a relevant manner. Finally, the multiplicity of institutions oriented to the promotion and support of services exports that do not have any kind of institutionalized coordination becomes an obstacle to the implementation of the support itself.

Chilean strategies for services export promotion

This research carried out an analysis of the perception of key actors regarding the results of the different attempts to increase services exports and create a solid new export sector in Chile. Chile has made limited efforts to promote exports of services, as discussed above, and has failed to promote this sector to diversify the export matrix. The reality is that, beyond the negotiation of free trade agreements, the efforts have been modest and very recent. In order to answer the question, interviews were carried out with a series of stakeholders from the public and private sectors, as well as international, academic and non-governmental organizations. The results of the interviews allowed the identification of three overlapping levels, in a hierarchy ranging from macro problems to more technical and regulatory aspects.

In the first level, we grouped the considerations on economic doctrines and business cultures. This point refers to us two reasons: on one hand, the penetration of a neoliberal model with a conception of subsidiary State embedded in all levels of society. It is a State that has limitedly promoted the service industry as a consequence of the predominance of ideologies or political philosophies that privilege minimal State intervention. On the other hand, is the existence of an entrepreneurial class that hasn’t had the strength or will to modify the productive and the export patterns.

The second level deals with considerations of specificity in the service industry and associated economic aspects. There is a high ignorance of the services sector and its potentialities, particularly regarding those of greater complexity, which explains, in some way, the low effort to support this sector. In turn, this lack of understanding can be explained by the following reasons: the recent irruption of services in the commercial world, their coexistence in a world designed and structured for goods, and the methodological difficulty in measuring them.

Given the short-term vision and ignorance regarding the service sector, the situation is exacerbated by the lack of institutional coordination in Chile to address the issue. This absence has meant that the programs are dispersed, have divided resources and have little continuity. Likewise, there is a primacy of finance in the decisions of economic policy, under a marked vision of nonintervention in the productive processes. Amongst economic considerations, the policy of no exchange rate intervention was another pillar of the model’s severity, coupled with the volatility that has historically affected companies to reach third markets. The tax structure has also been an impediment, in particular due to double taxation.

In another aspect, the scarcity of skilled labor is diagnosed as one of the obstacles to the development of a sector that is intensive in human capital. Finally, a low impact of openness is identified, a process in which it was almost magically entrusted as an option for services to reach external markets, in addition to the absence of a public-private action system.

The last level reviews specific service-oriented policy, instrument and sectorial considerations. ProChile and CORFO are the object of deep criticism, which, in many cases, are linked to the foreground analyzed, associated with economic doctrine and business culture.

Since the end of the field work, some new policies had been implemented. In July 2015, a Public-Private Technical Committee was created. Its mission is to identify, analyze and evaluate the measures implementation that promote services exports, to ratify that they are feasible in the context of the regulations and norms and the budgetary restrictions. In March 2016, a package of 22 measures to boost productivity and increase the economic growth capacity was launched focused on three areas: financing of new initiatives, agenda for promotion and expand the definition of service to include them in the 0% VAT benefit when exporting. Since June 2016, the SNA has a new services classification, to make easier to apply the benefits to service exporters. These new attempts to promote services export may overcome some of the problems identified in the research but not all of them. Therefore, finally, we may suggest some policy recommendations, which address aspects ranging from macro to micro:

It is recognized that the model has penetrated the different social strata and that the State’s size makes it impossible to generate aggressive industrial policies. For this reason, promoting and guiding small enterprises requires a lot of resources and it is more difficult to internationalize them, so it is possible to restrict the aid to large companies with the condition that they work with the small ones.

The Government must create strategies and intervene. The debate is whether this should be done with vertical promotion policies or not. If the State does not choose winners, sectors would not develop.

In order to move towards better services development policies, there is a need to raise greater ambitions. There must be a law that defines the modification of the basket as a priority, and that determines coordinated institutions with the necessary resources. ProChile should be part of the Ministry of Economy and respond to an internal industry development plan, not only to demand. It needs to be empowered to eliminate some systemic failures, as well as to develop business capacity and design international marketing strategies. Inter-agency coordination should be improved.

International certifications should be encouraged and disseminated so that services’ providers can understand and use them.

The financial sector must raise its understanding of services of greater complexity, so that there are incentives for entrepreneurship.

Public-private partnership is urgent for the country development, structured is such a way that there are shared risks in areas of national interest.

Tourism services should be encouraged and a definition of the type of tourism that the country aspires to position in the world can be given, as well as a boost to the human capital needed to promote this activity.