Introduction

In the last decade, young sports participation has increased (Feeley et al., 2016). Childhood and adolescence sports participation is at one of its highest levels, although the evidence of benefit at the level of muscular, skeletal, social relationships and affections is clear (Eime et al., 2013; Hiremath, 2019). In recent years, a growing concern for early sports specialisation has revealed a series of problems associated with physical and psychological stress and interference in decision-making by external agents. (Bruner et al., 2014; McKay et al., 2019; Whitley et al., 2018). Besides, there is still a debate about the philosophical and ethical arguments that support sports (Beamish & Ritchie, 2006). (It is suggested that the situation derived from the pandemic be reviewed in the judgments expressed in the previous paragraph and, in the case of Beamish & Richie (2006), it would be appropriate to update it to a more recent one.

Sport specialisation is defined as year-round training, usually more than eight months of participating in a single sports discipline or discarding all sports to focus only on one (Myer et al., 2016). Some authors agree that specialisation occurs because of the influence of the parents and legal guardians (Baxter-Jones & Maffulli, 2003; Padaki et al., 2017) and because of the perception by the athletes that specialisation should increase the possibility of participating in elite level and receiving an athletic scholarship (Hill & Simons, 1989; Jayanthi et al., 2013).

The sport specialisation in children and young people has been reported since the competition in Olympic disciplines increased, mostly in Eastern Europe and the United States of America, caused by the national systematised selection processes and the implementation of programs for the development of future Olympic and world champions (Myer et al., 2016). The popularised idea that to achieve expertise in a specific skill it is necessary a considerable amount of hours of practice, which initially was thought for musicians but was later extrapolated to athletes (Jayanthi et al., 2013), reinforces the idea that sports specialisation is the optimal way for the physical and technical development of children and young people in sports. This idea must be taken with caution because it can exclude areas such as social and psychological as fundamental factors, working in intrinsic motivation and skill transferability (Baker et al., 2009).

On the other hand, diversification promotes that children participate in a wide variety of motor and sports activities through free play and on other occasions around a sport, under an informal environment, providing the possibility of maximising the child’s motor skills, physically, emotionally, and cognitive areas (Côté et al., 2009).

Considering the evidence around the early sport specialisation, there is still controversy around the ideal age to begin and the risks, disadvantages, and benefits of athletic participation in children and young people (Myer et al., 2015b). The specialists in human movement sciences and sports medicine have acknowledged the potential of sports specialisation for enhancing athletic performance in some sports (Hume et al., 1993), but also recognise that schools should promote sport diversification to develop integral capacities in children and young (Hill & Simons, 1989). Also, some authors agree that early sport specialisation does not lead to a competitive advantage over those who developed around multi-sport participation (Feeley et al., 2016), unlike, those elite athletes that specialised later tend to achieve better results at a higher level of performance (Carlson, 1988; Güllich & Emrich, 2006; Moesch et al., 2011).

Previous studies have focused on issues related to determining the types, characteristics, and general content of early specialisation items and examining how early specialisation has been defined and measured (DiSanti & Erickson, 2019; Hecimovich, 2004; Mosher et al., 2020; Zoellner et al., 2021), but systematic work focused on the advantages and disadvantages of up-to-date early sport specialisation are scarce.

Through a systematic review, this review aimed to explore the evidence of the benefits and disadvantages of young sport specialisation and diversification over the past 20 years. This review will discuss theoretical scientific literature to describe the state of the science around sport diversification and early sport specialisation.

Methods

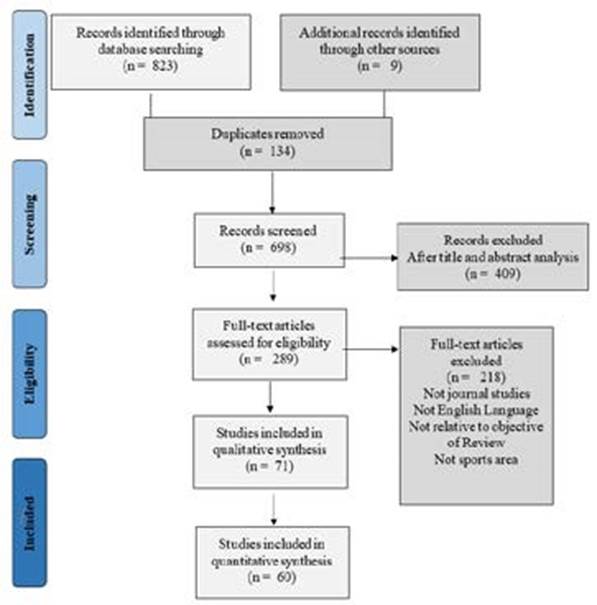

A narrative literature review was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009; Moher et al., 2015). Three authors (D.R-V, C.A-M, and M.H-M) independently considered risk-of-bias questions using a 4-point scale ranging from low and high risk of bias options. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved using consensus between three authors, as mentioned. The internal quality of each study was assessed using the Office of Health Assessment and Translation (OHAT) Risk of Bias Rating Tool (OHAT, 2015).

Data source

A literature review has been performed using web search engines-databases (SportDISCUS (EBSCO), PubMed Central (MEDLINE), ScienceDirect, Web of Science (WoS)), and Google Scholar. The following descriptors were used for the online literature search: ¨sport¨, ¨specialisation¨, ¨multisports¨, ¨early specialisation¨, ¨youth specialisation¨, and ¨diversification¨. The Boolean keys ¨AND¨ and ¨OR¨ were used to link the words prementioned. All searches were conducted from MayJuly 2019, and all references were extracted and imported to an open-source research tool (5.0.64, Zotero, USA).

Data Selection

Articles search was limited by title/abstract and year as advance search settings. The investigation was limited to articles published from 2000 until 2020. Duplicates were eliminated following previous guidelines (Rathbone et al., 2015). Studies were incorporated if the following inclusion criteria were fulfilled: a. descriptive, experimental, systematic, or narrative review, b. studies were analysing early specialisation and diversification and its physical, social, and cognitive impact, c. articles in English. Studies were selected based on the title and abstract analysis and were examined in full text, and those that met the inclusion criteria were selected to explore the information reported. No studies were excluded based on participants characteristics such as sport or disciplines and age or on study design.

The procedure followed during study extraction or exclusion is presented in figure 1:

Data Collecting The final extracted articles were analysed in full text and data about authoring, year of The final extracted articles were analysed in full text and data about authoring, year of publication, design (article type), topic (early specification and diversification), other sample/data characteristics (sample size, age, sport or discipline) and outcomes were systematized in a descriptive table.

Table 1 Specialisation or diversification in sports Evidence Database (PEDro) Scale Scores of Critically Reviewed Articles

| 1. Eligibility criteria were specified | 2. Subjects were randomly allocated to groups (in a crossover study, subjects were randomly allocated an order in which treatments were received) | 3. Allocation was concealed | 4. The groups were similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators | 5. There was blinding of all subjects | 6. There was blinding of all therapists who administered the therapy | 7. There was blinding of all assessors who measured at least one key outcome | 8. Measures of at least one key outcome were obtained from more than 85% of the subjects initially allocated to groups | 9. All subjects for whom outcome measures were available received the treatment or control condition as allocated or, where this was not the case, data for at least one key outcome was analyzed by “intention to treat” | 10. The results of between-group statistical comparisons are reported for at least one key outcome | 11. The study provides both point measures and measures of variability for at least one key outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wiersma (2000) | YES | YES | NO | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Watts (2002) | YES | YES | NO | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Gould et al., (2002) | YES | NO | NO | NO | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Mojena & Ucha (2002) | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Soberlak & Cote (2003) | YES | NO | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES | NO | YES |

| Baker et al., (2003) | YES | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | YES | NO | YES | YES |

| Hecimovich (2004) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Gustafsson et al. (2007) | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Rose et al. (2008) | YES | YES | NO | YES | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Baker et al. (2009) | YES | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | YES | NO | YES | YES |

| Strachan et al. (2009) | YES | NO | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Balaguer, et al.(2009) | YES | NO | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Kaleth & Mikesky (2010) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Malina (2010a) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Gould (2010) | YES | NO | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES |

| Caruso (2013) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Merkel (2013) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Martínez & Javier (2014) | YES | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Sheridan et al. (2014) | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Jayanthi et al. (2013) | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Fergurson & Sternstern (2014) | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| DiFiori et al. (2014) | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Myer et al. (2015b) | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Horn (2015) | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Smucny et al. (2015) | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Hastie (2015) | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Goodway & Robinson (2015) | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Hall et al. (2015) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | YES | NO | NO |

| Brenner (2016) | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | YES | NO | NO |

| Correa et al., Tierling, Treter, de Souza & Abaide (2016) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| García-Parra et al., González & Fayos (2016) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Fabricant et al. (2016) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| LaPrade et al. (2016) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| McFadden et al., Bean, Fortier & Post (2016) | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Feeley et al. (2016) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Post et al. (2017) | YES | NO | NO | NO | YES | NO | NO | YES | NON | YES | NO |

| Blagrove et al., Bruinvels & Read (2017) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Normand et al. , Wolfe & Peak (2017) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Smith et al. (2017) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Sluder et al. (2017) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| McGuine et al. (2017) | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | NO | YES | YES |

| Wilhelm et al. (2017) Pasulka et al. (2017) | YES | NO | NO | YES | NO | NO | NO | YES | NO | YES | YES |

| Bell et al. (2018) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Jayanthi et al. (2018) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Garinger et al. (2018) | YES | NO | NO | NO | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Watson et al. (2018) | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Bell et al. (2018) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Walters et al. (2018) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Anderson et al. (2018) | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES | NO | NO | YES | NO | YES | YES |

| DePhillipo et al. (2018) | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| DiStefano et al. (2018) | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Russel & Molina (2018) | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Post et al. (2019) | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Heydinger (2019) | YES | YES | NO | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Weekes et al., (2019) | YES | YES | NO | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Moseid et al. (2019) | YES | YES | NO | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| McDonald et al. (2019) | YES | YES | NO | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Field et al. (2019) | YES | YES | NO | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES |

Results

Table 2 shows the studies of the last two decades extracted from databases concerning young specialisation and diversification with its main outcomes. A total of 60 studies were found in a total of five on-line databases (from a total of n= 832 studies).

Table 2 Studies conducted in the last two decades about early specialisation and diversification by author, year, sport, and design.

| 1 | Wiersma (2000) | Review | Young Athletes | +Eating disorders | +Remain in sport | Less intense training |

| +Amenorrhea | +Social Development | Allow other sports | ||||

| +Development injuries | Training Breaks/Recovery | |||||

| +Overuse injuries | Long-term periodization | |||||

| Greater affectation in females | Multiple sport Practice | |||||

| 2 | Watts (2002) | Review | High School | +Eating disorders | +Multiple Motor Skills development | Long-term periodization |

| Students | +Overuse injuries | Set realistic goals | ||||

| +Burnout | +Learn of different values | Stress management | ||||

| Failure as a learning experience | ||||||

| 3 | Gould et al. (2002) | Original | 10 US Olympic | +Social isolation | NR | Read psychological needs |

| Research | Champions | |||||

| 4 | Mojena & Ucha (2002) | Original Research | 40 Spanish Elite Athletes | +Burnout | NR | Stress management |

| +Sport Withdraw | ||||||

| +Social isolation | ||||||

| 5 | Soberlak & Cote(2003) | Original Research | 4 Elite Athletes | NR | development | Multiple sport Practice |

| 6 | Baker et al. (2003) | Original Research | 15 Coaches | NR | +Decision making expertise | Multiple sport Practice |

| 16 Athletes | ||||||

| 7 | Hecimovich (2004) | Review | Young Athletes | +Eating disorders | NR | Set realistic goals |

| +Overuse injuries | Training Breaks/Recovery | |||||

| +Delay sexual maturation | Long-term periodization | |||||

| +Amenorrhea | Play sports accessible | |||||

| +Cardiac disfunction | Health controls | |||||

| +Sport Withdraw | Multiple sport Practice | |||||

| +Sedentary future | ||||||

| +Burnout | ||||||

| +Social isolation | ||||||

| 8 | Gustafsson et al. (2007) | Original Research | 980 youth athletes | +Burnout (individual sports) | NR | Less intense/volume training |

| 9 | Rose et al. (2008) | Original Research | 2721 high school athletes | +Injuries | NR | Less intense training |

| 10 | Baker et al. (2009) | Original Research | 28 athletes | +Decision making expertise | NR | Quality training instead of volume |

| Multiple sport Practice | ||||||

| 11 | Strachan et al (2009). | Original Research | 74 youth athletes | + level of physical and emotional exhaustion | +higher levels of physical/emotional exhaustion | New pathways of sport development |

| +higher levels of physical/emotional exhaustion | ||||||

| +higher levels of physical/emotional exhaustion | ||||||

| +integration of sport and family | ||||||

| . | ||||||

| 12 | Balaguer, et al. (2009) | Original Research | 225 young internationally elite tennis players | +importance of motivational variables as correlates of burnout | NR | Motivational to prevent burnout |

| 13 | Kaleth & Mikesky(2010) | Review | Children (6 to 12 years) | = endocrine system | +Training philosophies | Multiple sport Practice |

| Muscular system | -Injuries | |||||

| +strength | +Multiple Motor Skills | |||||

| -Hypertropia | development. | |||||

| Nervous system | +physically active lifestyle | |||||

| = process of myelination | ||||||

| Cardiovascular system | ||||||

| = benefits of regular exercise | ||||||

| 14 | Malina (2010a) | Original | Young Athletes | +social isolation | NR | Multiple sport practice |

| research | +overdependence | |||||

| +Burnout | ||||||

| +Risk of overuse injury | ||||||

| 15 | Gould (2010) | Original | Elite Athletes | NR | +Parents support | Parents support |

| research | +Talent development | Talent development was easier | ||||

| for young people who learned | ||||||

| habits fostered by their talent | ||||||

| rather than training. | ||||||

| 16 | Caruso (2013) | Review | Children | +Injuries | +Physical abilities | Multiple sport practice |

| +Burnout | +Cognitive abilities | |||||

| +Rate cardiovascular | ||||||

| 17 | Merkel (2013) | Review | Young Athletes and children | +Physical activity | NR | Recreation as critical part of children’s lives |

| -Risk of obesity | ||||||

| -Minimizes development of | ||||||

| chronic disease | ||||||

| +Improves motor skills | ||||||

| +Stress to be an elite player | ||||||

| 18 | Martínez & Javier(2014) | Original research | Young Athletes and adults (13 a20 years) | +Burnout | NR | Less volume of sessions |

| 19 | Sheridan et al. (2014) | Review | Children, adolescents, and adults (10 a 22 years) | +Pressure from coaches and parents | NR | Coaches have a fundamental role as supporters |

| 20 | Jayanthi et al. (2013) | Review | Children and adolescents | +Psychological stress | +Enjoyment | Multiple sport practice |

| +Dropping Out of Sports | -Fewer injuries | |||||

| +Injury | +Longer participation contributing to the chances, of success. | |||||

| 21 | Fergurson & Stern(2014) | Review | Children | +Overuse injury | +Gain competitive edge | Multiple sport practice |

| -Proper rest | +Develop skills faster | |||||

| -Interest in sport | +Early talent recognition | |||||

| +Social isolation | +Increase opportunity for | |||||

| +Burnout | scholarships or | |||||

| +Overdependence | professional contracts | |||||

| 22 | DiFiori et al. (2014) | Review | Children andadolescent | +Risk overuse injuries Burnout | NR | Multiple sport practice |

| 23 | Myer et al. (2015b) | Review | Children and adolescents | +Repetitive Technical Skills and High-Risk Mechanics | NR | Less intensity and volume in sessions |

| +Overscheduling and | Multiple sport practice | |||||

| competition | ||||||

| +Psychological burnout | ||||||

| +Primary Injury and Effects of | ||||||

| Fear of Reinjury | ||||||

| 24 | Horn (2015) | Review | Children | +Overuse injury | +Gain competitive edge | Multiple sport practice |

| -Proper rest | +Develop skills faster | |||||

| -Interest in sport | +Early talent recognition | |||||

| +Social isolation | +Increase opportunity for scholarships or professional contracts | |||||

| +Burnout | ||||||

| +Overdependence | ||||||

| 25 | Smucny et al (2015). | Review | Children and adolescent | +Detrimental both physically and emotionally | NR | Multiple sport practice |

| 26 | Hastie (2015) | Review | Young athletes | +Unnecessary Intense training and specialisation before puberty | NR | Train less and Multiple sport practice |

| +Long competitive goals. | ||||||

| 27 | Goodway & Robinson (2015) | Review | Children and adolescent | =Elite level performance in sport. | NR | Motor skill programs (not sport-specific) |

| +Sport specialisation benefits in gymnastics. | Multiple sport practice | |||||

| +Youth sport injury. | ||||||

| +Incidence and severity of overuse injuries. | ||||||

| =Lifelong physical activity patterns. | ||||||

| 28 | Hall et al. (2015) | Original research | Female adolescent athletes | +Risk of anterior knee pain | NR | Specialisation led to more injuries |

| 29 | Brenner (2016) | Clinical Report | Young athletes | +Overuse injuries | NR | Multiple sport practice |

| +Overtraining | ||||||

| +Burnout | ||||||

| 30 | Correa et al. (2016) | Review | Youth athletes | -Respect maturation and development stages and motor, coordinative and conditioning capacities’ optimal window of trainability | +General development of fundamental motor skills and technical/tactical skills. | Competitions only after the players have their basic techniques and patterns of play under control |

| +Sports dropout | ||||||

| 31 | García-Parra et al. (2016) | Review | Man and woman | +Burnout due to training loads | NR | Motivational aspect |

| +Burnout due to specialisation | Prevention burnout | |||||

| 32 | Fabricant et al. (2016) | Review | Children and adolescent | Incidence of injury Overuse injuries | NR | Increased risk of overuse injury due to specialisation |

| 33 | LaPrade et al. (2016) | Review | Children and teenagers | +Overuse injuries | +Long-term sports | Avoid excessive sports |

| +Burnout | performance | commitments. | ||||

| +Decreased motivation for participation | +Enjoy physical activity | Monitor burnout. | ||||

| +Lifelong recreational | Have a balance between sports, school, and friends. | |||||

| +Sports withdraw | sports participation | |||||

| 34 | McFadden et al. (2016) | Original research | 61 youth male hockey players | +Psychological needs dissatisfaction | -Psychological needs dissatisfaction | Specialize in a certain sport after age 12. |

| +Demotivation | +Mental health | Coaches and parents offer a positive, supportive, and empowering motivational climate that will lead to low levels of mental illness | ||||

| +Lack of autonomy | +Wellness | |||||

| 35 | Feeley et al. (2016) | Review | Young Athletes | High level of achievement | NR | Educate parents, coaches, trainers, and physicians on the risks of early sport specialisation and the early signs of injury. |

| +Overuse injuries | ||||||

| 36 | Post et al. (2017) | Original research | Young Athletes | +Overuse injuries | NR | Long-term periodization |

| Promote the fun | ||||||

| Multiple sport Practice | ||||||

| 37 | Jayanthi & Dugas(2017) | Review | Young Athletes | +Overuse injuries | +Leads to success | Sports Specialisation at the end of adolescence |

| +Burnout | +Promote motivation | |||||

| +Leave the sport | -Less injury | |||||

| +More participation | ||||||

| 38 | Blagrove et al. (2017) | Review | Female teenage athletes | +Female athlete triad | NR | Multiple sport Practice |

| +Amenorrhea | Long-term periodization | |||||

| +Overuse injuries | ||||||

| +Limit motor skills | ||||||

| 39 | Normand et al. (2017) | Review | Young Athletes | Professional status | +Healthy psychological development | Sport specialisation only after the development of specific skills, abilities, and psychological maturity. |

| Early recognition | ||||||

| +Social pressure | +Participation in multiple youth sports allow for periods of active rest and recuperation | |||||

| +Overuse injuries | ||||||

| +Burnout | ||||||

| +Sense of autonomy | ||||||

| +Multiple motor skills | ||||||

| 40 | Smith et al. (2017) | Review | Young Athletes | + increase injury risk, | NR | Before making sweeping recommendations against early sports specialisation, solid data are needed. Only research done with rigorous methodology will provide answers |

| -decrease social opportunity | ||||||

| - life satisfaction | ||||||

| +Skill acquisition required for competitive success in many sports | ||||||

| 41 | Sluder et al. (2017) | Review | Young Athletes | + Coaching & skill instruction | +Development of pro social behaviours and personal | An athlete’s early specialisation in a sport does not guarantee a future in that sport at an elite level Based on available evidence. Multiple sport practice |

| + Skill acquisition through deliberate practice accumulation | . +Promotes development of intrinsic motivation. | |||||

| + Time management | +Promotes motor skill development | |||||

| + Peer relationships within group | ||||||

| . | ||||||

| +overuse injury | +Increased connection to community, integration of family, and better health outcomes | |||||

| -Cost development of lifetime sports skill | ||||||

| +Burnout to include emotional and physical exhaustion | . | |||||

| +Social development issues | ||||||

| 42 | McGuine et al (2017). | Original research | Young Athletes | +risk of musculoskeletal lower extremity | NR | Specialisation leads to a higher risk of musculoskeletal lower extremity injuries than athletes with low specialisation |

| 43 | Wilhelm et al. (2017) | Original research | Children and adolescent | +serious injuries during their professional career | NR | Higher rate of serious injury if specialisation development was selected |

| 44 | Pasulka et al. (2017) | Original research | Children and adolescent | +proportion of overuse injuries | NR | Athletes in individual sports may be more likely to specialize in a single sport than team sport athletes. Single-sport specialized athletes in individual sports also reported higher training volumes and greater rates of overuse injuries than single-sport specialized athletes in team sports. |

| 45 | Bell et al. (2018) | Review and meta- analysis | adolescent | +overuse injury | NR | Sport specialisation is associated with an increased risk of overuse musculoskeletal injuries |

| 46 | Jayanthi et al. (2018) | Original research | Children and adolescent | +sport injuries | NR | High-income athletes reported more serious overuse injuries than low-income athletes, possibly due to higher rates of sports specialisation, more hours per week playing organized sports, a higher proportion of hours per week in organized sports relative to free play and increased participation in individual sports |

| 47 | Garinger et al. (2018) | Original research | 351 Division II and III specialized and multiple-sport athletes | +perfectionistic | NR | Stress associated with burnout and perfectionistic |

| +burnout | Specialized athletes’ lower levels of burnout | |||||

| +stress | ||||||

| 48 | Watson et al. (2018) | Original research | 49 Female youth soccer players | +stress | -Stress | Sport specialisation is associated with significantly worse mood, stress, fatigue, soreness, and sleep |

| +Fatigue | -Fatigue | |||||

| +Soreness | -Soreness | |||||

| -Mood | +Mood | |||||

| -sleep quality | +sleep quality | |||||

| 49 | Bell et al. (2018) | Systematic Review with Meta analysis - | N/A Young multi- sport specialized | +risk an overuse injury | None | Sport specialisation is associated with an increased risk of overuse musculoskeletal injuries |

| 50 | Walters et al. (2018) | Systematic Review | N/A Young multi- sport specialized | +Resistance training decrease risk of injury and overtraining | NR | Correct supervision of Coaches and physical educators engage in healthy training for sport |

| +increased repetition and increasing the risk of injury | ||||||

| + early sport dropout | ||||||

| 51 | Anderson et al. (2018) | Original research | 5 Female of Division I college soccer team | +lower extremity injury | NR | Lost an average of four days of training |

| 52 | DePhillipo et al. (2018) | Case Report | 1 Young alpine skier | +Patellofemoral articular cartilage defect | NR | healthcare professionals must be educated on the known causes of knee effusions and influence early sport specialisation may result in overuse injuries to knee joint cartilage. |

| 53 | DiStefano et al. (2018) | Cross-sectional | 355 Youth athletes | +good neuromuscular control | Multi-sport participation may reduce injury risk in youth athletes | |

| 54 | Russel & Molina(2018) | Original research | 77 female high school athletes | = sport motivations and burnout | Specializers and non- specializers young athletes are similar levels of sport motivation and burnout. | |

| 55 | Post et al. (2019) | Original research | 647 Female youth athletes | +Daytime sleepiness associated high levels of specialisation, overuse injury traveled regularly | NR | Specialisation= increased daytime sleepiness |

| 56 | Heydinger (2019) | Original research | 24 athletes | = risk injury | NR | Sports specialisation in high school does not ever affect the rate of injury in collegiate athletics |

| 57 | Weekes et al., (2019) | Original research | 602 High school students | +Hours practicing their primary sport | -injured playing multi-sport | Relationship between more hours of sport specialisation and injure associated |

| +Injured playing their primary sport | ||||||

| 58 | Moseid et al. (2019) | Original research | 259 Youth elite athletes | = Increase injury risk | NR | Single sport and specialisation appear to represent risk factors for injury or illness |

| 59 | McDonald et al. (2019) | Original research | 143 youth elite- level wrestlers | +more serious injuries | NR | Athletes, coaches, and parents should consider the risk of injury associated at the sport specialisation |

| 60 | Field et al. (2019) | Original research | 10,138 youth athletes | +Females increased risk of injury | NR | Sports specialisation can be associated with a greater |

| +Females association vigorous activity and develop injury= no clear pattern of risk | volume of vigorous activity and injury risk. Parents and coaches must be aware of volume training threshold |

+: increase; -: decrease; =: no effect, NR= Nonspecific reports.

Discussion

Benefits and disadvantages of diversification

Diversification of sport at an early age has been an element that literature over the years has stood out as a practice that collaborates in the fast development of athletes. This modality is characterized by a free play model with a high component of fun, sport variability, and non-rigid rules, providing the possibility that infants explore other types of experiences. Both with peers and with other ages, diversification offers greater possibilities of social relationships that help in the development of emotional skills which influence self-regulating behaviours and emotions are essential in the competition (Brenner & Fitness, 2016).

Physical

When children are allowed to participate in a development model based on diversification, they are influencing the development of neuromuscular patterns which are associated with the prevention of injuries at later ages or in young athletes (DiFiori et al., 2014a; DiStefano et al., 2018; LaPrade et al., 2016a). This allows higher performance at the sports level as it offers significant possibilities of staying present in competitions. In multiple studies involving elite athlete in field hockey, ice, basketball, and triathlon they reported that before becoming Olympic or high-performance international athletes they trained and competed in multiple sports, in addition to their primary sport, unlike fellow they only compete at the national level that practiced a single sport since childhood (Baker et al., 2003, 2009; Soberlak & Cote, 2003; Vaeyens et al., 2009).

Also, understanding motor development as an area that is responsible for studying human motor behaviour and the changes in the underlying processes that interact during the growth and maturation of the individual, is that diversification at an early age offers higher and better experiences that allow performing transfers from one sport to another sport or other activity. It must be analysed under the premise that a more significant amount of motor experiences offers greater possibilities to influence the maturation processes of systems such as the central nervous system or the senses. (Goodway & Robinson, 2015).

According to Fransen et al. (Fransen et al., 2012) when determining the differences in the physical condition and motor coordination in children from 6 to 12 years who specialized versus those who practiced more than one sport, they found that diversified children, specifically with ages between 10 and 12 years, obtained better physical condition and motor skills. These results are attributed to the full range of motor resources that these subjects had (Hecimovich, 2004).

Social

The practice of any sport takes place in a social environment and requires, among other things, the ability to interact effectively with coaches, parents, and peers (Gould, 2010). According to the evidence (Strachan et al., 2009), in an investigation that 74 young athletes, classified in specialists (in sports such as swimming, gymnastics, and diving) and diversified (by the practice of multiple sports), diversified athletes showed greater sports integration with the family and a more reliable link with the community, while specialists reported difficulty in relating to their peers and higher levels of emotional exhaustion. Contemplating that there is a fundamental right of children to an open future (Torres, 2015).

Psychological

As stated by Caruso (2013) notes that providing the child with a multi-sport environment can foster an authentic preference for sports so that he can continue with more structured and productive practice in late childhood and even in adulthood. Multiple authors have mentioned that early sports diversification leads to success, due to the intrinsic motivation that stems from fun, enjoyment and competition of children through participation in various sports (Baker et al., 2003, 2009; Jayanthi et al., 2013). There are fewer reports of burnout related to sports practice in non-specializer than in those that specialized earlier (Russell & Molina, 2018).

Sports activities require a high degree of cognitive-perceptual skills, to make the right decisions during competitions, besides affective skills, to have control of their emotions (Côté et al., 2009). In this way, diversification is linked to a longer sports career (Gould, 2010). Indeed, diversification is related to better long-term health consequences and promotes a holistic approach, using a variety of sports to better develop the athlete’s lifestyle (Blagrove et al., 2017).

Benefits and Disadvantages of specialisation

Specialisation tendency was born in Eastern Europe, mainly with the purpose of competition. Talent identification and development programs were constants in the pursuit of a medal by these countries (Malina, 2010a). Parents have a fundamental role in specialisation in sports, industry, television, society, and educational programs to emphasize their process in achievement. That was the beginning of sport organization for children (Malina, 2010a). This led to the creation of expectations from the parents and the labelling of children based on their talents, this increased the belief that specialisation was the right path for children’s development.

On the other hand, early sports specialisation seems to be associated in many cases with adverse physical and psychological effects (Brenner, 2016; Feeley et al., 2016; Sluder et al., 2017). Given this, several studies have shown the presence of overuse injuries, overtraining and burnout in these athletes; as well as, possible affectations at the nutritional level and musculoskeletal and psychological maturation that undoubtedly cause the impossibility of sports practice and loss of continuity (Anderson et al., 2018; DePhillipo et al., 2018; Myer et al., 2015a).

On the other hand, early sports specialisations may have an impact on the isolation of their friends and partners, as well as, alterations in family relationships together with the manifestation of a greater co-dependency of third persons due to the loss of control of their own lives, bringing with it possible maladaptive social behaviours (Corrêa et al., 2016; Malina, 2010a; Smith et al., 2017).

Physical

The greatest benefit of specialisation is the acquisition, development and proficiency of motor skills related to success in a specific sport. A child who practices certain skills and abilities on a regular basis and even more with a certain scientific basis may develop and improve those skills better than another who performs less periodically and irregularly, such as diversification (Wiersma, 2000).

A series of investigations have shown the consequences at a physical level that can be obtained a specialisation in the early ages (Bell et al., 2018; Fabricant et al., 2016; Myer et al., 2015a; Smucny et al., 2015a; Walters et al., 2018), which highlights injuries from overuse, overtraining and lack of sleep among the main problems and those that can be see increased mainly when the specialisation begins before the age of 12, independently of age, sport or other contextual factor (Feeley et al., 2016; Field et al., 2019; LaPrade et al., 2016a; McDonald et al., 2019; McGuine et al., 2017; Moseid et al., 2019; Myer et al., 2015a; Post, Trigsted, et al., 2017; Torres, 2015; Weekes et al., 2019; Wilhelm et al., 2017). Additionally, individual sport athletes tend to specialize more than team sport athletes, so there is a greater incidence of sport related injuries in individual sports specializers (Pasulka et al., 2017).

Within a large number of possible consequences linked to the early specialisation, the injuries by transit in the ages between 6 to 18 years, the results to the most recurrent and mainly to the works that are characterized by the repetitive actions with high volumes, frequencies and intensities of work (Brenner, 2016; Post, Bell, et al., 2017), what brings with it a large number of hours of specialisation, those with a strong relationship of injuries reaching values between 55% and 70% (DiFiori et al., 2014c; Rose et al., 2008; Smucny et al., 2015a). And in the case of injuries such as tendinopathies, stress fractures and apophysitis, they are the most recurrent affecting the bone, muscular and ligamentous structures; In addition, premature development can alter the aspects of motor coordination and flexibility deficit product of musculoskeletal imbalances and connective tissues (Hall et al., 2015; Kaleth & Mikesky, 2010; Malina, 2010a) and could compromised growth and maturation (Malina, 2010b).

In a case report (DePhillipo et al., 2018), found cartilage lesions and osteochondral defects in a young alpine scheme, excessive and repetitive use of microtrauma because of early specialisation. Also, the economic and social level they have an important incidence, (Jayanthi et al., 2018), show differences significantly in young athletes with ages of 8 to 18 years, in which socioeconomic level was higher with the greater occurrence of overuse injuries and where this situation is associated with a greater number of hours of sports practice.

Social

Specialisation requires that children understand the value of commitment. And apparently, they learn to value the investment of energy, time, and emotions, which is essential for sporting success (Wiersma, 2000). Additionally, sports could create an enabling environment for development activities such as cooperative skills, behaviours in favor of a group environment and close relationships, because this sport is social by

Despite the above, at the social level the intense training that involves sports specialisation at an early age can cause young athletes to develop problems of self-concept and social skills (Merkel, 2013). According to (Ferguson & Stern, 2014; Normand et al., 2017) this damages the construction of social relations and unleash social isolation (Malina, 2010a). From this perspective, some elements such as high training volume and frequency of sessions, athlete's parents and coaches expectations could lead athletes to abandon the sport before reaching their peak. (Baker et al., 2003) due to burnout states (Malina, 2010a). In addition, these authors claim that the commitment required for sporting success usually obstructs the normal process of developing interpersonal skills and identity during childhood, because it can lead to familial disorders and rivalry among peers (Callender, 2010; Heydinger, 2019).

According to (Wiersma, 2000) in an interview with teenage athletes, those who were successful but who abandoned the sport indicated that they did so due to a set of life experiences that lead to the development of a self-concept, which the sport in some way prevented them from experiencing. In other words, as an athlete increases participation in a single sport, opportunities for social interaction outside of that sport may be less likely.

Psychological

Although sports specialisation and the sport itself could cause experiences where self-esteem and self-perception are improved because of the achievement of goals and objectives, there are negative psychological effects that are often difficult to recognize (Horn, 2015; Wiersma, 2000). Additionally, it is important to understand the potentiality of early sport specialisation to develop psychological needs satisfaction in youth (McFadden et al., 2016). However, they are very important aspects to consider for the maintenance of sports practice over time (Watts, 2002). One of the most damaging aspects of specialisation is emotional and mental physical exhaustion, also known as “Burnout syndrome” (García-Parra et al., 2016). This exhaustion is mainly induced, when participation in a sport exceeds the rewards of its participation, which causes a decrease in performance, lack of concentration, mental fatigue and even depression (Mojena & Ucha, 2002).

This exhaustion of the athlete from a multidimensional psychological perspective has been related to early sports specialisation, where marked manifestations of stress and anxiety, loss of intrinsic motivation, added to a lower sensation towards the sports context is shown with recurrence in this population (DiFiori et al., 2014b; Jayanthi et al., 2018; Sheridan et al., 2014). Indeed, sport specialisation has been associated with worse mood, fatigue, sleep quality, stress, soreness with no relation to age or training load (Garinger et al., 2018; Post et al., 2019; Watson et al., 2018).

Aspects such as excessive schedules of sports practices, the low emphasis on physical fitness skills through enjoyment and applicable to life, along with the low application of valid and reliable tools to determine burnout states are some of the main triggers of these problems (Kaleth & Mikesky, 2010; LaPrade et al., 2016b; Torres, 2015).

Likewise, certain social and psychological characteristics associated with the development of excessive perfectionism of young people, coaches or parents are frequently observed aspects; For this reason, the monitoring related between the intensity of sports participation and their degree of specialisation coupled with the interaction with friends, school and any other type of extracurricular activities are essential for the well-being of young people (Sluder et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2017; Smucny et al., 2015.

However, the choice of a single sport can cause the athlete to lose the sense of enjoyment of the discipline, so, usually the athlete suffers psychologically (Gould et al., 2002). Studies previously conducted (Balaguer et al., 2009; Gustafsson et al., 2007; Martínez & Javier, 2014), reinforce this information, because when analysing the presence of this exhaustion in young elite athletes they found its presence in tennis athletes and other disciplines, arguing that the rigorous hours of intense training through specialisation can interfere with the benefits of sports participation. Also, based on the evidence shown, specialisation causes an increase in the probability of withdrawal and dropout from sports practice (Baker et al., 2009; Wiersma, 2000). Indeed, adults that reported early specialisation were less likely to still be active in their adulthood (Hastie, 2015).

Conclusion

It is clear and dates to the recent qualitative and quantitative scientific evidence; sports diversification and sports specialisation in children have advantages and disadvantages at a physical, social, and psychological level. These pros and cons are dependent on the objective with which the sporting activity is developed, in this case, it will depend on the type of process and the philosophical line of the sports centre, coaches, parents and children. What is clear is that the disadvantages of each process must be considered in the hands of the integral development of children. Additionally, considering that there are ethical and philosophical arguments to discuss even around high-performance sport (Beamish & Ritchie, 2006), and the rate of high-performance athletes compared to the whole population, politicians, educators, and parents should consider if the world needs new and better athletes or citizens? Indeed, some authors considered that excessive training processes may also be considered as a form of child abuse (Pipe, 1993), from a perspective a interpersonal violence psychological and physical (Vertommen et al., 2016; Witt & Dangi, 2018). That although it is true, sports specialisations are not a synonym of excessive training, the line between both practices is very thin, often leading to confusion and because of it the consequences are suffered by boys and girls.

Based on this evidence, the alternative of sport diversification at an early age is considered firstly, and then work around sport specialisation once the bases of strength, conditioning and neuromuscular training have been achieved, as well as a certain psychomotor maturation so that their sports performance and health are not compromised in the medium or long term. It is necessary to consider that few children manage to obtain a place in the sports elite or do not have the specific capabilities to achieve high performance (Wojtys, 2013), so for many of them, the education around sports will be the basis for the exercise of their citizenship as active people. It is suggested that in relation to this assessment, there be a slightly more detailed analysis in the conclusion, since it is a very relevant aspect that is not necessarily addressed in the sports specialisation in early childhood stages. Indeed, some authors considered that excessive training processes may also be considered as a form of child abuse (Pipe, 1993).

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of conflict interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article