1. Introduction

Different aspects of culture teaching and learning have become crucial components in the field of English as a Foreign Language (EFL). For example, textbooks and other teaching materials generally incorporate cultural components related to history, arts, architecture, music or literature, as well as traditions, customs, and other cultural practices in foreign countries. In addition to those, verbal and nonverbal communication, values, meanings, and beliefs when addressing culture could also be found in EFL teaching resources. However, these cultural aspects are commonly minimized and, in some cases, wrongly left aside in instructional programs which mainly focus on language content, skills or other subjects in a decontextualized fashion. One of the reasons why culture cannot be minimized is concluded in a study by Yeşil and Demiröz (2017):

(…) most of the educators in the field gather around the idea that the students should be presented cultural knowledge in order that they can acquire better communication and comprehension skills. In the same vein, the instructors strive to enact and incorporate academic tasks and make the cultural input comprehensible and applicable for the students. (p. 90)

When learning a foreign language, culture is implied in this process. The relevance of culture lies in the fact that each element in a language is enclosed in a given context. In order for language users to achieve successful communication, a deep understanding of cultural aspects should be met. If so, learners will be capable of developing intercultural communication competence, which is defined by Yi (2015) as: “one’s ability to conduct meaningful, appropriate, and effective communication with others of different cultural backgrounds” (p. 49). As a result, cultural differences may not necessarily have to be considered as an obstacle in communication; on the contrary, culture should become a resource for developing an understanding of the way people from different backgrounds interact.

An interest for featuring cultural aspects in textbooks, didactic materials, and courses has noticeably increased as a way to help students to get immersed in the underlying aspects of any language. For Tang (2006), there are goals to cultural learning in foreign language education that should be addressed, given the eminent relationship between language and culture:

Behavioral culture, particularly, has attracted vast attention from FL [foreign language] pedagogues because it is found to be an integral part of human communications whose meanings often do not lie in the linguistic items but in the social and cultural context as well in the physical evidence provided by proxemics, kinetics, and other paralinguistic modalities. (p. 87)

If language is best learned through communication and considered as the vehicle to culture, an equation can be traced between culture and communication. Therefore, language learning is enhanced if a myriad of cultural components is incorporated in foreign language teaching.

Culture can also be seen as the means for comparing and contrasting a target to a native culture. Choudhury (2013) explained that, “The goal behind teaching culture in EFL should be inculcating intercultural communicative competence among learners, rather than propagating or showing superiority of the target culture over native culture” (p. 23). In other words, learners should be aware that learning about another culture does not necessarily imply giving up their own. It can be argued that lack of notions concerning cross-cultural communication may lead to conflicts such as a reduced empathy for a target culture. If cultural content is approached in the language class, students will be likely to overcome these gaps. Moran (2001) stated, “Without a solid, well-rounded knowledge of the culture, [language] learner’s ability to develop cultural explanations will be limited or superficial” (p. 146). For instance, broadening learners’ understanding of cultural practices minimizes failures in communication, i.e. breakdowns or misunderstanding, and maximizes success in their attempt to communicate interculturally and effectively.

The scope of this study sheds light on the implications of culture integrated into the language learning process of university students enrolled in an English major (henceforth, referred as BI1), by developing the following research objectives:

To inquire about students’ understanding and perceptions toward the learning of culture in different courses within BI’s curriculum.

To assess EFL teaching practices when approaching culture.

2. Literature Review

When integrating culture into language syllabi, learners might develop positive and/or negative attitudes toward foreign cultures and different ethnicities. Henze (1999) explained that reforms in curricular approaches can minimize the gap between what learners may perceive as unknown or even awkward, and what they may find fascinating in terms of cultural knowledge broadening. Henze (1999) reported on a study about different curricular approaches to develop positive interethnic relations among students; if these approaches are implemented through time, “(…) students [can] become cognizant about their own ethnic and culture identity, learn how to respect and appreciate those who are different, and learn to question and challenge the inequities that surround them (…)” (p. 548).

Considered as the fifth language skill (aside from the skills of listening, speaking, writing and reading), Brown (1994) affirms that culture and language “(…) are intricately interwoven so that one cannot separate the two without losing the significance of either language or culture” (p. 165). EFL teachers seek to prepare their students to successfully interact with English speakers from different cultural backgrounds. Nevertheless, the inclusion of culture into EFL instruction remains a dichotomy by either treating it as a separate subject matter or as another element to be incorporated in daily-basis language classes. As an attempt to foster cultural practices, Bateman (2002) reported on a study in which the students (English speakers) interviewed native speakers of Spanish about their culture. As the main finding, this scholar found out that it is possible to engage students not only cognitively but also affectively and behaviorally as to produce attitudinal changes toward culture learning.

When integrating culture into language learning, teachers might seem skeptical to the extent of excluding cultural components from their classes. Other contexts may partially incorporate cultural components, or methodological strategies may lack of a specific purpose. To illustrate, Sercu, Mendez and Castro (2004) concluded that,

Spanish teachers [of English as a foreign language] do not consider culture teaching all that important; nonetheless, teachers support intercultural objectives and deem that it is important to promote the acquisition of an open mind; their teaching practice can as yet not be characterized as intercultural. (p. 99)

From this study, it can be inferred that EFL settings sometimes might either leave culture aside from language learning or include it only as a supplement. Additionally, Zamora and Chaves (2011) considered that, “(…) the fact that teachers may recognize the connection between language and culture and also respect the traditions and beliefs of other groups does not mean that they have the training to teach those ideas to their students” (p. 284).

Regarding strategies to weave cultural components into language teaching, Dianbing and Xinxiao (2016) carried out an exploratory study on challenges and solutions when integrating language and culture; the practices implemented by the teacher participants in this study have been summarized as follows:

Bridging the cultural gap: Teachers provide opportunities to be exposed to authentic contexts from the target culture (i.e. field trips or exchange programs).

Involving native and non-native instructors: The authors reported that students do benefit from the advantages of being taught by the two kinds of instructors.

Inviting students’ discussion on culture: Students recognize salient features of a given culture and compare them with those from their own cultural background through discussion elicited in class.

Spending quality time in preparing the culture classes: Teachers must be aware that researching about culture guarantees specificity when delivering cross-cultural insights into language instruction.

Moran (2001) also exemplifies that teachers can resort to a myriad of options when incorporating cultural components in their classes, by asserting:

There is no shortage of useful materials and valid techniques for teaching culture. Teachers can employ critical incidents, cultural assimilators, culturegrams, role-plays, cultural simulations, field experiences, ethnography, experiential activities, cross-cultural training techniques, values clarification, film, video, literature, realia, authentic materials, and many more. (p. 6)

General views or perspectives on the teaching of culture and how it relates to language might determine how meaningful students find cultural topics approached in the EFL classroom. As Dai (2011) claimed, “The learning of target-language culture can improve students’ understanding of the target language, enrich their ability of understanding (…) of the world and cultivate cultural awareness” (p. 1035). Consequently, it is essential to explore practices for the instruction of culture in EFL deeply.

3. Methodology

3.1 Research design

The present study follows a quantitative approach in which the collected data was analyzed descriptively and tranversely since it accounts for the cultural learning and teaching experiences of both students and teachers among all academic levels of the BI major during the second academic cycle in 2017. Regarding the scope of the research, it is exploratory in nature as it attempts to reveal strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and challenges of the BI curriculum in terms of practices and perceptions for the topic under study. According to Creswell (2003), this approach “(…) employs strategies of inquiry such as experiments and surveys, collects data on predetermined instruments that yield statistical data” (p. 18).

3.2 Participants

This study gathered data from 74 students: 32 from the first level, 13 from the second level, 16 from the third level, and 13 from the fourth level in the BI program. All students are Costa Rican and were enrolled in the major of English at Sede Interuniversitaria, Alajuela. According to the Escuela de Literatura y Ciencias del Lenguaje (2015), the study plan developed for this major includes 41 courses, comprising 132 university credits. Specifically, 105 of these credits belong to subjects that are compulsory and taught in the target language (i.e., subjects directly managed by the BI program). Three credits correspond to a course on Spanish writing, and the remaining 24 credits are assigned to either general courses from other disciplines or elective courses that might or might not belong to their major.

BI students have opportunities to explore culture from different places through the instruction of the target language in their EFL classes. According to the BI curriculum, two courses focus on culture as a subject matter, and another one combines culture and literature from the United States. The other courses focus on language skills and content.

By the time the study was carried out, the major was being taught by 11 faculty members. They are Costa Rican and hold postgraduate studies in different fields such as EFL, linguistics, applied linguistics to EFL, English literature, and English-Spanish translation.

All participants agreed to be part of the study via an informed consent form and upon approval of the coordinator of the English department. It is important to clarify that neither student nor teacher sample population was selected, so the participants represent a convenience sampling process of data collection.

3.3 Instruments

First of all, a survey was administered to students (see Appendix A). Particularly, this first instrument included close-ended items to collect students’ background and open-ended questions to find out what kind of learning experiences students had had and would like to have in the courses from the BI major. A four-point Likert scale measured by levels of agreement and disagreement was also part of the instrument to inquire about learners’ perceptions about learning culture. To guarantee a whole sample data gathering, the researchers visited the classrooms, informed students about the study, and administered the survey during class time. Students who were absent during the data collection phase were later given the instrument by their own professors.

Secondly, professors were interviewed via an online questionnaire (see Appendix B). This instrument comprised both open and close-ended questions that allowed the researchers to confirm the teaching practices implemented in the BI major. Professors were sent the instrument, but only five out of 11 faculty members completed it.

Both instruments were pilot tested and validated with a smaller sample of students and teachers from another campus to detect possible cultural biases and misunderstanding of technical terms on the subject.

3.4 Procedures

The results collected through structured instruments (i.e., surveys and questionnaire) were mainly summarized and compared. Indeed, data collected was analyzed and presented using statistical techniques. Main results were categorically classified and reported to inform on the knowledge, perceptions and practices of cultural aspects from the students’ as well as teachers’ perspectives. To illustrate possible improvements based on the needs from the practices implemented in the teaching of culture, the researchers synthesized the most mentioned suggestions provided by the participants.

4. Results

From the student survey, one of the items was intended to show which countries or ethnicities learners had learned culture from. Indeed, participants reported countries where English is spoken officially (e.g., mainstream countries like the U.S. or the U.K.), but they also expressed having learned cultural elements from Asian countries (e.g., India or The Philippines), European countries (e.g., Germany or Belgium), and Latin American countries (e.g., Argentina or Mexico). Evidence showed that students had been learning about culture from different ethnicities.

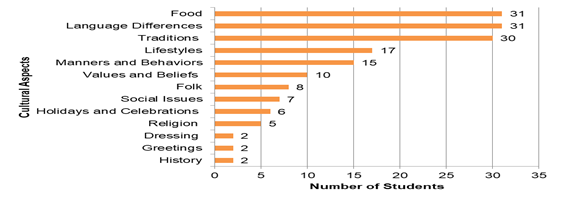

In addition, learners were asked about cultural aspects addressed in their courses. The results revealed that the three most reported cultural elements were food (n=31), language differences (n=31), and traditions (n=30), while and the three least reported cultural elements were greetings, dressing, and history, as shown in Figure 1.

Source: Own elaboration from survey to students at the BI major from Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica, 2017

Figure 1 Students' background knowledge about cultural aspects

Besides, participants mentioned in which courses from the BI major they had mostly learned about cultural aspects. First and second level students expressed that they had been exposed to this kind of learning in courses focused on integrated skills, oral expression, pronunciation, and culture per se. Likewise, third and fourth level counterparts stated having learned culture in oral expression, culture, elocution, literature, and linguistics courses. Data from the questionnaire informed that professors acknowledged highly approaching culture in courses aimed at integrated skills, culture, literature, and oral expression, aside from the courses on culture. As it can be inferred, courses focused on language skills (e.g. reading and writing) or language areas (e.g. grammar or pronunciation) are examples of contexts where culture plays a minimal or a nonexistent role.

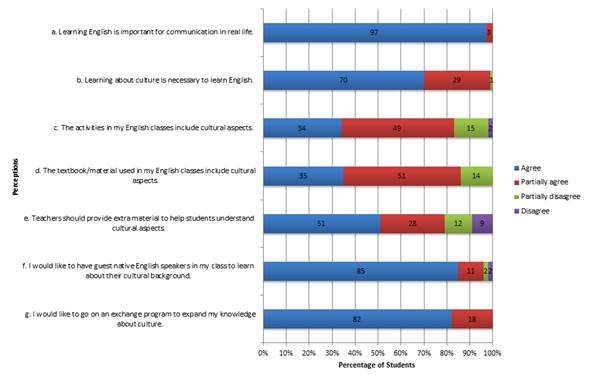

From another item in the student survey, their perceptions about a series of statements on cultural practices were collected. The majority of students (97%) agreed that learning English plays an important role in real life communication; similarly, 70% of them agreed that culture is needed to learn this target language. Regarding classwork implemented in the BI classes, most learners partially agreed that activities and textbook/materials embrace cultural aspects, being shown as 49% and 51%, accordingly. Similarly, 51% of the students agreed their professors should include additional material to facilitate the understanding of cultural phenomenon. In the same way, most learners (85%) agreed they would like to have guest speakers in their classes, and 82% agreed they would like go on an exchange program for culture learning purposes, as seen in the Figure 2.

Source: Own elaboration from survey to students at the BI major from Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica, 2017.

Figure 2 Students' perceptions on cultural learning experiences in the major

Additionally, the teaching staff indicated that, in order to enhance authenticity when teaching culture, the most frequent sources were videos, music, internet, photographs, food samples, newspapers, and literature; being artifacts, radio, ethnographic observations, and studies in the area of sociolinguistics the least frequent resources.

About the strategies implemented to teach cultural components, professors showed preference for discussions, interviews, reading activities and research projects; over other techniques which were ranked in a lowest frequency: games, culture capsules, fairs, or assimilators. Below, some of the most salient insights provided by the professors on how to improve the teaching of culture within the major are presented:

To make professors aware of the importance of truly considering it [i.e. culture] as much as possible in all the courses they teach to the ESL students.

[To] Help ss [students] to have access and active participation in foreign exchanges or at least keep communication with English [native] speakers.

(...) to implement more activities that are related to culture and also to dedicate more time to culture in most classes.

(...) to encourage students to debate about day to day topics such as news, TV programs. Critical thinking has to be encouraged. In this way, students can use a second language but also take a position when talking about national and international issues.

[To have] More fieldwork and research projects; more readings dealing with the topic in its depth rather than simple "biased" interpretations of their interconnectedness.

Moreover, students reported on ideas that could be useful for their own culture learning. Most students agreed with promoting cultural practices that resemble the strategies found in the study by Dianbing and Xinxiao (2016), as seen in Table 1.

Table 1 Description of students' ideas for culture learning throughout the levels of the major

| First Level | Second Level | Third Level | Fourth Level |

| - Videos - Books - Practice with other people - Music - Documentaries - Exchange programs - Real life communication - Native speakers - Field trip - Audios - History | - Capsules - Games - Role plays - Visit places - Practice with international students - Native speakers - Music - Debates - Videos - Movies - Research projects - Reading - Having guests - Visual aids - Exchange Programs | - Native speakers - Presentations - Capsules - Research projects - Audios - Books - Field trips - Conversational workshops - Interviews - Movies - Role plays - Fairs - Specialists | - Exchange programs - Native speakers - Fieldtrips - Research projects - Audiovisual material - Idioms - Books - Presentations |

Source: Own elaboration from survey to students at the BI major from Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica, 2017.

Another survey item was aimed at inquiring if culture helps students improve their communication skills. Most learners identified culture as an essential component within their major; understanding other’s language, behavior, and differences and having meaningful interactions were some of the reasons why learners considered culture as an enhancing vehicle for successful communication. Oppositely, one student from the second level expressed, “You don't need all aspects of culture to understand a person;” and another student from the third level stated, “It is easier to learn different countries when you live it in your own.” These two answers implied attitudes which contradict the culture and language equation previously mentioned by Tang (2006).

About the role of culture in language teaching, some of the professors’ answers indicated,

Culture helps to understand the use of language in social context, learn about history for being discussed in the English class and understand concepts which may be useful for defining roles, reducing stereotypes and overcome social differences.

The role of culture is crucial to have students communicate in an appropriate way by following the acceptable behavior in the other culture.

The connection between culture and language has been widely explored in ancient (e.g. Roman, Greek, and Sumerian) and modern times. Most studies agree that both have a profound influence in the way we perceive ourselves and others in terms of identity patterns, the context and the way we relate to it. In other words, teaching a language requires the teaching of culture.

Without knowing about the culture of the language we are learning, very often, we can't fully understand its true meaning. We may understand the literal words, but not the whole gist.

The role of culture in language teaching becomes essential taking into account that it complements the linguistic, communicative, and sociolinguistic competence. When learning certain languages, culture goes hand in hand; the context is fundamental to understand the message. For example, it is really hard to learn Mandarin and Japanese if someone has not had contact with the culture.

In brief, students were aware of the importance and need of including cultural aspects in their classes. They claimed to include more activities to be immersed in this context and provided some ideas to promote and emphasize the role of culture within the BI curriculum. In a like manner, professors highlighted the relevance of culture in language learning to help students find differences, avoid stereotypes, understand social gaps, behave in an appropriate way, and improve communication skills.

5. Conclusions

The present study reveals that both students and teachers consider that culture plays a significant role in language learning and teaching within the BI major. Even though culture is taught explicitly in two of the BI courses as a subject matter, findings informed that this component has been approached in most of the courses to some extent. Nonetheless, broadening and deepening the way culture is addressed along the study plan requires some rethinking and planning in terms of methodological practices. As argued by Castro (2007), “Some of the difficulties that teachers may consider when deciding whether to include culture in their classes are time, evaluation, teachers’ preparation, and resources” (p. 204). Such challenges might hinder culture learning. Teachers, indeed, might avoid developing cultural contents imply a more profound approach for cross-cultural communication. In other words, most commonly-taught cultural elements such as food, traditions, and language differences seem to be the core in the contents students at the BI are exposed to. Based on the suggestions made by the participants of this study, there is a lack of authentic and experiential cultural contact. All in all, learners achieve a deeper intercultural communicative competence when they build the necessary skills to fully interact with other language users from different origins, contrast their own culture with others’, and reflect on behaviors, beliefs and values, among other aspects. Learners should be guided, followed up and supported by their professors who need to be well-prepared for teaching culture. This means they should invest time preparing the class and researching about cultural aspects to bring meaningfulness into the courses.

Despite the fact that BI students have learned about some cultural aspects and felt generally satisfied with the cultural exposure they have had, a shift must be made to integrate culture into the EFL curriculum language learning meaningfully. The present study reveals a need, from both students’ and professors’ points of view, to a more dynamic view of culture that improves interethnic relationships and promotes critical thinking on cultural topics. The researchers conclude that culture teaching should be targeted through experiential, authentic and reflective strategies throughout all the BI courses. For example, it is suggested promoting events such as fieldtrips, culture fairs or exchange programs in order to provide learners with contextualized cultural encounters. If these events were permanently executed, students can benefit from opportunities for immersion in both language and culture learning.

Historically, the faculty members of the BI program are non-native professors. Following the ideas proposed by Dianbing and Xinxiao (2016), native teachers should be involved in a language program to weave cultural integration. The researchers propose that teachers with such profile become guest professors. Another alternative would be undertaking collaborative projects between the professors in the BI program and those from universities abroad. As a result, local students will be able to interact with language peers through social media as a way to bridge geographical distances, while exchanging and comparing features on language learning experiences and cultural aspects from their own backgrounds. Classes could also be enriched by inviting exchange students to campus.

BI students should be assigned more tasks to broaden their cultural understanding, fill their gap of cultural of misunderstanding, and promote the interaction with and immersion into a variety of cultural backgrounds. Regarding the practices implemented by teachers participating in this study, there is a myriad of strategies and resources that professors can resort to for promoting intercultural communicative competence. Particularly, this competence must first be strengthened within the curriculum of the BI. Only if cultural practices in this major are improved, can learners be truly benefited from weaving culture into the language classroom.