Introducción

Microalgae are a diverse and polyphyletic group of single-cell photosynthetic organisms, both eukaryotes and prokaryotes, which can easily grow in a wide range of habitats under photoautotrophic conditions (1). To date, microalgae have gained considerable attention as a low cost model for the production of a wide range of commercial goods, such as food and animal feed additives, ingredients in cosmetics, or as value-added compounds (pigments, therapeutic proteins, fatty acids) (2). More recently, microalgae have been also the object of an increasing interest as alternative host for recombinant protein production because of their economic benefits and ecofriendly characteristics (3), (4).

Despite their inherent advantages as biological factories for the large-scale production of recombinant molecules (5), (6); the number of microalgae species that have been genetically modified has increased slowly and it is still scarce (7). One of the main obstacles which limits the development of microalgae genetic engineering is the lack of plasmid vectors with all the essential elements for their transformation (8). Among the critical elements for an efficient expression of the biomolecules, the use of specific promoters for microalgae stands out; however, the lack of endogenous promoters is one of the main drawbacks to achieving an efficient transformation (9), (10).

The promoters are cis-acting regulatory regions that direct the transcription of a gene. Functionally, a promoter is a DNA sequence located upstream (towards the 5’ end of the coding region of a gene) that includes the binding regions for transcription factors (11). In microalgae, some heterologous promoters, including the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV35S), ubiquitin promoter, and NOS, have been used for the expression of reporter genes (12). Nevertheless, due to the unique nuclear characteristics of the microalgae, the gene expression under heterologous promoter control has been inefficient, exhibiting relatively low and fluctuating levels (13).

In contrast, the most effective promoters have derived from highly expressed microalgae genes; for instance, in the transformation of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, the non-coding 5’ region of the small RuBisCO (RBCS2) subunit gene and the heat shock protein 70A (HSP70A) have been widely used (8), (14). While the use of endogenous promoters is almost optimized in model algal strains, only heterologous promoters from plant systems have been used in industrial microalgae strains like Chlorella sp. (2).

For species of the Chlorella genus, which represent a specialized group of green microalgae that can produce high protein levels, genetic transformation development has been slow and research on promoters derived from Chlorella is still in its early stage (15). Therefore, the identification and isolation of new and effective endogenous promoters is highly required to achieve an efficient expression of foreign genes in Chlorella sp. (16). In this study, we predicted an endogenous Chlorella promoter sequence in the 5′ upstream region of the alpha-tubulin gene from Chlorella vulgaris. The function of this promoter was confirmed through the expression of an antibiotic resistant gene in Chlorella sorokiniana.

Materials and methods

Chlorella strain and culture conditions

Chlorella sorokiniana used in this study came from the microalgae culture collection of the Costa Rican Institute of Technology Biotechnology Research Center. Cells were routinely grown and maintained at 25°C in BG-11 medium (17) under 12/12 h light and dark cycle and 200 µmol m−2 s−1 light intensity.

Antibiotic sensitivity test

The tolerance of C. sorokiniana to streptomycin and spectinomycin antibiotics was evaluated through a sensitivity assay, streaking the plate with 50 µL of the microalgae culture (106 cells mL-1) in BG-11 agar supplemented with different concentrations of streptomycin and spectinomycin (0, 25, 50, 75, 100, 125, and 150 mg L-1). The plates were incubated inverted in darkness for two days, at room temperature, before being exposed to light conditions (200 µmol m−2 s−1), and the microalgae growth was determined 8 days later.

Vector design and codon optimization

The alpha-tubulin gene (tua1) of Chlorella vulgaris microalgae (GenBank accession: D16504.1) was identified through a BLAST search (18). Using the information provided in the 5’ non-coding region, exons, and introns of the DNA sequence (19), a minimal promoter region (proximal promoter) was identified; this sequence was named “α-1 tubulin promoter”. The location and distribution of putative cis-acting elements in α-1 tubulin promoter was analyzed using PlantCARE (20).

The α-1 tubulin promoter was used to drive the expression of the aadA gene, which codifies the streptomycin-3”-adenylyltransferase enzyme and provides resistance to the streptomycin antibiotic. The nucleotide sequence of the aadA gene was obtained from the pAPR52 plastid transformation vector (GenBank accession: EU497669.1). To achieve an efficient translation of the enzyme, an optimization in the use of the codons was performed, in order to adapt the sequence of the aadA gene to the C. sorokiniana genome following the codon table for C. sorokiniana microalgae, obtained from Kazuza database (21).

Afterwards, the sequence optimization was performed using Optimizer (22). The promoter sequence and the streptomycin resistance gene were synthesized along with the rep (pMB) and ntpll (KnR) gene sequences (resistance to the kanamycin antibiotic) of the pUC57-Kan vector for their replication in E. coli, through General Biosystems Inc.. The new vector was identified as pChlorella_1.

Electrotransformation

C. sorokiniana was transformed with pChlorella_1 vector through electroporation. Briefly, 30 mL of the C. sorokiniana culture (OD750 = 0,3-0,5) were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min and the supernatant was discarded. Then, the pellet was resuspended in 5 mL of GeneArt® MAX Efficiency Transformation Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA), and after its incubation for 30 min at room temperature, it was centrifuged once again and the supernatant discarded.

The cells were resuspended in 1250 µL of the same reagent, and 4 μg of previously Xbal linearized pChlorella_1 plasmid were added and incubated at 4°C for 5 min. A volume of 250 µL of the cell-DNA mix was transferred to a cold electroporation bucket (in an ice bath) and the electroporation was performed using an Eppendorf Eporator® (Eppendorf AG, Germany), with 1 pulse at 1000 V (~ 30 ms).

After the electroporation process, the cells were transferred to a well plate with 5 mL of BG-11 medium with 40 mM sucrose and they were incubated for 2 days at 120 rpm and light conditions (200 µmol m−2 s−1). After the incubation period, the cells were harvested through a centrifugation at 2500 rpm for 5 min, resuspended in 100 µL of BG-11 medium and streaked in Petri dishes with BG-11-agar supplemented with 125 mg L-1 of streptomycin (selective medium). The Petri dishes were incubated for 2 days at room temperature in the dark, and then they were exposed to continuous light conditions.

PCR analysis of transformants

To confirm that C. sorokiniana was transformed, a “colony-PCR” of resistant colonies was performed, using specific primers for the streptomycin resistance gene: pchlorella_1_Forward 5’-TGTCTCTGGTTTGGTGGTCA-3’ and pchlorella_1_Reverse 5’-CAGCAGGTCGTTGATCAGG-3’. The amplified product was expected to be of 385 pb. The PCR reaction was carried in a total volume of 25 μL, containing 2,5 μL of Dream Taq 10X Buffer, 1 μL dNTPs (2 mM), 1 μL of each primer (10 μM), 0,25 μL of DreamTaq DNA Polymerase (5U mL-1), 14,25 μL of nuclease-free water and 5 μL of colony lysate.

A thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems Veriti®) was used for all reactions and the following thermal profile was applied: 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 sec, alignment at 55 °C for 30 sec, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min, with a final extension for 10 min at 72 °C. The PCR products were analyzed through a 1,5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Results and discussion

Antibiotic sensitivity test

The growth of C. sorokiniana was complete inhibited at a 125 mg L-1 streptomycin concentration, while the minimum spectinomycin concentration that allowed the complete inhibition of the microalgae growth was 150 mg L-1 (table 1). Therefore, 125 mg L-1 of streptomycin was the concentration chosen for the posterior selection of the transformed colonies. It is known that streptomycin affects the growth and the photosynthetic activity of C. vulgaris through the inhibition of the synthesis of chloroplast proteins (23) and that a 40 mg L-1 concentration is enough to completely inhibit its growth (24). However, C. sorokiniana presents a certain level of tolerance to aminoglycoside antibiotics (25), which relates to the high antibiotic concentration that was required to suppress the algae culture, when compared to reports from other species.

Vector design and codon optimization

The identified proximal promoter sequence corresponded to 281 nucleotides upstream of the ATG start codon (figure 1). In silico analyses revealed the presence of 9 potential cis-acting elements including 1 TATA- and 2 CAAT-boxes (table 2). The eukaryotic consensus TATA-box is considered an essential element in determining the transcription start site (TSS) and also serves as binding site for the components of the basal transcription machinery; it is typically located at the −30 or −31 position, relative to the TSS in metazoans (26). However, the identified TATA-box was located at −82 nucleotides upstream of the ATG start codon; this kind of motif localization is common in yeasts, where the TATA-box is usually located at the −200 to −50 relative to ATG (26).

Figure 1 Nucleotide sequence of the Chlorella vulgaris α-1 tubulin promoter and its more relevant predicted motifs.

The TATA-box sequence found in Chlorella vulgaris α-1 tubulin promoter (TACAAAA) has minor deviations in relation to the consensus TATA box DNA sequence. This type of variation, called weak TATA box, has been reported in different eukaryotic cells and also facilitates the interaction with the TATA-binding protein (27), (28). The CAAT box, also found in the promoter, is known for its capability to regulate the transcription frequency (29).

Other studies reference the use of tubulin promoters for microalgae transformation; for instance, Davies et al. (30) fused the promoter region of the β2-tubulin gene to the coding region of a genomic clone of arylsulfatase (ars), to form a chimeric tubB2/ars sequence, leading to an efficient microalgae transformation. Also, Hallmann and Sumper (31) achieved the functional expression of the Chlorella sp. HUP1 gene in Volvox carteri under the control of the constitutive promoter Volvox β-tubulin. Considering these previous examples, α-1 tubulin promoter from Chlorella vulgaris is proposed as an effective promoter for the transformation of Chlorella sorokiniana.

The aadA codon optimized sequence obtained a 69,8 % GC content (compared with a 53 % content of the original gene), which increases its likelihood to Chlorella sp.´s genome (67,2%) (32) and its possibility to be translated efficiently. The designed vector (including the promoter and the aadA sequences) consisted of 3797 bp and included the sequences necessary for its replication in E. coli (figure 2).

Figure 2 Map of the designed pChlorella_1 vector. α-1 tubulin P: strong promoter, native from Chlorella vulgaris, which drives the expression of the aadA; addA gene: gene that codes for streptomycin-3 “-adenyltransferase and confers resistance to streptomycin; rep (pMB1): allows a high copy number replication and growth in E. coli; KnR: kanamycin resistance gene, it allows the selection of the plasmid in E. coli.

Electrotransformation and PCR analysis

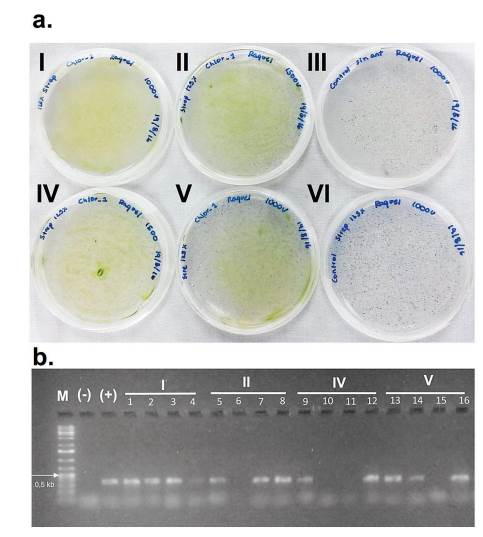

The transformation of C. sorokiniana with pChlorella_1 plasmid was induced through electroporation. For a higher transformation efficiency, the plasmid was linearized using XbaI restriction enzyme (33). The GeneArt® MAX Efficiency Transformation Reagent was used, which is a commercial reagent for the transformation of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii that increases the permeability of the membrane. However, other authors have treated Chlorella sp. through osmosis with sorbitol, mannitol, KCl, CaCl2 and HEPES, obtaining a similar effect (34). After the electroporation process, microalgae growth was observed in the streptomycin selective medium, evidencing the positive result of the transformation. The negative control (electropored microalgae without the plasmid) was not able to survive in the medium with antibiotic (figure 3-a). The transformed microalgae were subjected to a direct PCR of random colonies to identify the aadA gene present in pChlorella_1. The PCR products showed positive results, achieving the expected size of approximately 400 pb. Therefore, it was possible to confirm the integration of the promoter sequence and the resistance gene in the nuclear DNA of the microalgae (figure 3-b). The results demonstrated that the modified permeabilization membrane protocol, as well as the voltage used are adequate for the transformation of C. sorokiniana.

Figure 3 Transformation of C. sorokiniana with pChlorella_1 vector. a. Growth, in a selective medium, of C. sorokiniana transformed with pChlorella_1 (III and VI negative controls). b. Proof of the presence of the aadA gene in C. sorokiniana by colony polymerase chain reaction. The aadA gene was confirmed in all selected colonies except 6, 10, 11 and 15. M, 1-kb DNA ladder; (+) positive control, pChlorella_1 plasmid; (-) negative control; lanes 1-16, randomly selected colonies.

Conclusion

In this research, it was possible to achieve an efficient transformation through the electroporation of Chlorella sorokiniana with the pChlorella_1 vector. Our results proved the capacity of the Chlorella-α-tubulin promoter to express a foreign antibiotic-resistance gene in C. sorokiniana cells. Further research is required to determine the stability and strength of this new promoter, as well as the addition of new genetic elements, including the multiple cloning site, intron, UTR. The stable transformation of the microalgae has been a slow process due to the reduced heterologous gene expression; hence, research of endogenous promoter sequences is essential in order to accomplish an efficient heterologous gene expression, especially in microalgae used for industrial production like those from Chlorella genus.