Introduction

Nesting and feeding habitats of six of the seven species of sea turtles in the world are distributed in Mexico, and sea turtle migratory corridors include coastlines with national jurisdiction (Márquez, 1990). Sea turtles and humans have interacted for thousands of years, and sea turtles have been a source of food since the beginning of the first civilizations, including in ancient Mesopotamia (Frazier, 2003). In Mexico, sea turtle harvesting started in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and it is estimated that between 1965 and 1970, more than 2 million sea turtles (mostly olive ridleys) were captured (Márquez, 1996; Peñaflores et al., 2000). This practice, together with other human activities such as egg extraction, destruction of habitats in nesting areas, and bycatch, has had an impact on the decline in sea turtle populations (Behera et al., 2016; Pandav et al., 1998; Pritchard, 1996; Spotila, 2004); therefore, in 1966, the first turtle camps for study and conservation were established, and in 1990, a total and permanent ban of the capture of all species of sea turtles in Mexico was declared (DOF, 1990).

The olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) is considered the most abundant sea turtle in the world, and its main nesting sites occur on the East coast of India and the coasts in the Eastern Pacific, mainly in Costa Rica and Mexico (Abreu-Grobois & Plotkin, 2008). This species nests between July and January, with two nesting strategies: solitary and “arribada”; the latter is a unique nesting strategy of the genus Lepidochelys in which thousands of females arrive to nest synchronously on specific beaches for several days (Márquez, 1990; Pritchard, 2007). In Mexico, solitary nesting areas extend from the coast of Baja California Sur to the coast of Chiapas (CONANP, 2011). Currently, Mexican legislation considers this species “endangered” (DOF, 2010); it remains “vulnerable” according to the red list of threatened species of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (Abreu-Grobois & Plotkin, 2008) and is included in Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES, 2014).

Because olive ridley sea turtles do not reach sexual maturity until approximately 13 years (8-18 years) of age (Márquez, 1996; Zug et al., 2006), assessments of nesting trends over time are necessary to implement actions and effectively manage current conservation programs (Richardson, 2000). At Playa Escobilla, the most important arribada beach in Mexico, sustained recovery has been reported, with an increase from 200 000 nests in 1990 to more than one million nests in 2010 (CONANP, 2011); however, evaluations on solitary beaches are rare (Ariano-Sánchez et al, 2020; da Silva et al., 2007; Hart et al., 2018; James & Melero 2015; Viejobueno Muñoz & Arauz, 2015). Evaluations at nesting beaches are necessary to identify current nest trends, predict future outlooks and make appropriate management and conservation decisions for the benefit of the population of sea turtle under study (Balazs & Chaloupka, 2006; Ceriani et al., 2019; Honarvar et al., 2016).

The Autonomous University of Sinaloa (UAS) began efforts to conserve and conduct research on sea turtles, and in 1976, it implemented the Sea Turtle Program (PROTORMAR-UAS), with the commitment to protect, conserve and research these species as well as their habitats. The program utilizes two biological stations, Santuario Playa Ceuta (SPC) and Playa Caimanero (PC), and continuous annual data on nest abundance and hatching success (HS) as well as problems such as poaching and nest predation have been collected. The objective of this study was to evaluate the nesting trends of olive ridley turtles at two beaches in Northwestern Mexico (40 years for SPC and 30 for PC) and to predict prospective nesting success over the next 30 years.

Materials and methods

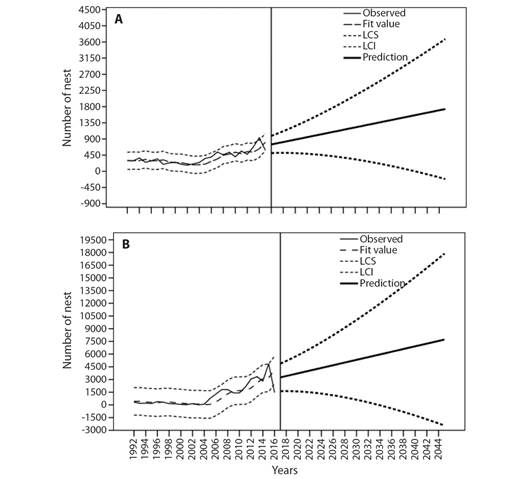

Study site: The study was conducted on two nesting beaches: SPC and PC. SPC is 37 km long and is located between the Cospita Estuary to the North (23°05’40” N & 107°11’42” W) and the Elota River to the South (23°52’43” N & 106°55’51” W); it is in the central region of the state of Sinaloa, Mexico, in the municipality of Elota (Fig. 1). SPC was declared a Reserve and Refuge Zone for the Protection, Conservation, Repopulation, Development and Control of Various Species of Sea Turtles (DOF, 1986) and as a sanctuary for olive ridley turtle nesting (CONANP, 2018; DOF, 2002). PC was designated a biological station in 1986; it is approximately 39 km long and is located between the mouth of the Presidio River to the North (23°05’29” N & 106°17’19” W) and the mouth of the Baluarte River to the South (22°50’15” N & 106°02’26” W); it is in the Southern region of the state of Sinaloa, Mexico, in the municipality of Rosario (Fig. 1). PC is not yet legally designated as a protected beach.

Fig. 1 Location of the nesting beaches of Lepidochelys olivacea in Northwestern Mexico managed by PROTORMAR-UAS.

Nesting data: During the nesting season (July-December) from 1976 to 1991 at SPC and from 1986 to 1991 at PC, night tours were carried out by university staff and field volunteers to collect eggs and conduct a census of nests (collected, poached and predated); however, during this period, it was not possible to cover the entire beach on a daily basis due to logistical and budget reasons. In 1992, more personnel and transport equipment were obtained, and the tours were carried out systematically. The tours 1) followed daily routes and 2) covered the entire study area, ensuring the counting of all nests in each season (Schoreder & Murphy, 2000). The collected eggs were incubated in hatchery or polyurethane boxes that were numbered consecutively to facilitate analysis (Mortimer, 1999). At the end of the incubation period, nest exploration was performed (45 ± 3 days) to estimate hatching success (HS) by dividing the number of eggs hatched (NEH) by the total number of eggs (TNE) incubated for each nest, with the formula HS = (NEH/TNE) × 100 (Caut et al., 2006). Later, the hatchlings were released into the sea during the night or at dawn during low tide when the waves were not very strong so the hatchlings could enter the sea easily and quickly, preventing predation. This research was carried out under agreements with and permits granted by the Subsecretaria de Gestión para la Protección Ambiental, Dirección General de Vida Silvestre (SGPA/DGVS/06306), which are renewed annually.

Data analysis: The total number of nests for each season, including collected, predated and poached nests, the HS for each beach each year were collected. The averages (with their standard deviations) of each of these parameters for the entire period were calculated, and a Mann-Whitney U test (P < 0.05) was performed to identify differences between the beaches with respect to the monitoring data. Spearman correlation analysis was used to assess correlations between the total nests registered (which included collected, predated and poached nests) and the study period. All statistical analyses were performed with SigmaPlot v11 software. Nest abundance in 2045 was predicted by a predictive time series model using IBM SPSS Statistics 23 software (Brown et al., 1975; Gil & Lobo, 2012). The prospective analysis was performed for the next 30 years (more than two generations) considering the average age at sexual maturity (13 years) of the olive ridley turtle (Márquez, 1996; Zug et al., 2006), with the assumption that mortality will remain constant due to the standardization of the years that PROTORMAR-UAS has performed work on the beaches.

Results

Registered and collected nests and predation and poaching: At SPC from 1976 to 2016, a total of 11 238 nests were registered, of which 9 755 were collected, 848 were predated, and 635 were poached (Table 1); at this beach, before 1992, the collection of nests was variable (mean= 99.4 ± 75.4 nests per year). This was because the same effort was not made for technical reasons, but in 1992, the effort was standardized, and since then, the number of nests was approximately 340.2 ± 164 nests/year, although there were nesting seasons with less than 200 nests/year (1995= 187, 1998= 186, 2001= 169, 2002= 157 and 2003= 188). In 2004, it was not possible to work due to budget constraints. At PC, only data from 1989 to 2016 were considered event though protection began in 1986; before 1989, there were technical and operational difficulties preventing consistent monitoring, and some data were lost. During the study period a total of 29 001 nests were registered, of which 24 379 were collected, 1 878 were predated and 2 744 were poached. The average number of registered nests before 2005 was 176.9 ± 110.1 nests/year, and after 2005, the abundance of nests increased to 2 180.9 ± 1 144.6 nests/year. The 2015 season had the highest nesting record (4 859 nests) (Table 1). When comparing the parameters between nesting beaches, no significant differences were identified (P > 0.05).

Table 1 Annual data on nests and eggs collected as well as predation and poaching of olive ridley turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) nests in Santuario Playa Ceuta (1976-2016) and Playa Caimanero (1989-2016)

| Santuario Playa Ceuta | Playa Caimanero | |||||||||

| Years | Registered nest | Collected nests | Protected eggs | Predated nests | Poached nests | Registered nest | Collected nests | Protected eggs | Predated nests | Poached nests |

| 1976 | 84 | 40 | 4 013 | 14 | 30 | - | - | |||

| 1977 | 129 | 112 | 11 414 | 12 | 5 | - | - | |||

| 1978 | 104 | 75 | 7 646 | 8 | 21 | - | - | |||

| 1979 | 65 | 48 | 4 993 | 5 | 12 | - | - | |||

| 1980 | 39 | 35 | 3 696 | 4 | 0 | - | - | |||

| 1981 | 52 | 47 | 4 774 | 5 | 0 | - | - | |||

| 1982 | 46 | 35 | 3 476 | 4 | 7 | - | - | |||

| 1983 | 72 | 47 | 4 993 | 4 | 21 | - | - | |||

| 1984 | 82 | 65 | 4 858 | 0 | 17 | - | - | |||

| 1985 | 67 | 51 | 6 448 | 5 | 11 | - | - | |||

| 1986 | 125 | 104 | 10 631 | 14 | 7 | - | - | |||

| 1987 | 208 | 179 | 15 720 | 23 | 6 | - | - | |||

| 1988 | 222 | 197 | 18 336 | 25 | 0 | - | - | |||

| 1989 | 61 | 61 | 6 076 | 0 | 0 | 124 | 117 | 11 710 | 1 | 6 |

| 1990 | 286 | 241 | 25 441 | 31 | 14 | 294 | 277 | 27 456 | 3 | 14 |

| 1991 | 300 | 253 | 24 441 | 32 | 15 | 205 | 193 | 18 351 | 2 | 10 |

| 1992 | 305 | 243 | 23 913 | 38 | 24 | 325 | 307 | 28 716 | 3 | 15 |

| 1993 | 294 | 240 | 30 047 | 21 | 33 | 187 | 176 | 15 853 | 2 | 9 |

| 1994 | 371 | 301 | 22 040 | 28 | 42 | 203 | 191 | 18 669 | 2 | 10 |

| 1995 | 251 | 187 | 14 930 | 9 | 55 | 165 | 155 | 14 046 | 2 | 8 |

| 1996 | 294 | 225 | 20 923 | 20 | 49 | 394 | 371 | 35 348 | 4 | 19 |

| 1997 | 348 | 343 | 30 785 | 2 | 3 | 318 | 300 | 29 111 | 3 | 15 |

| 1998 | 194 | 186 | 13 190 | 2 | 6 | 145 | 137 | 13 052 | 1 | 7 |

| 1999 | 237 | 219 | 24 069 | 7 | 11 | 129 | 122 | 11 168 | 1 | 6 |

| 2000 | 251 | 224 | 22 159 | 3 | 24 | 57 | 53 | 5 026 | 1 | 3 |

| 2001 | 196 | 169 | 18 474 | 8 | 19 | 30 | 28 | 2 873 | 1 | 1 |

| 2002 | 169 | 157 | 12 290 | 4 | 8 | 152 | 144 | 13 470 | 1 | 7 |

| 2003 | 208 | 188 | 19 166 | 18 | 2 | 12 | 10 | 903 | 1 | 1 |

| 2004 | - | - | - | - | - | 90 | 85 | 8 081 | 1 | 4 |

| 2005 | 246 | 239 | 26 872 | 3 | 4 | 781 | 737 | 67 262 | 7 | 37 |

| 2006 | 361 | 319 | 27 649 | 11 | 31 | 1 288 | 1 215 | 104 558 | 12 | 61 |

| 2007 | 398 | 388 | 35 176 | 3 | 7 | 1 815 | 1 712 | 151 899 | 17 | 86 |

| 2008 | 536 | 467 | 40 470 | 43 | 26 | 1 813 | 1 710 | 153 394 | 17 | 86 |

| 2009 | 462 | 392 | 23 673 | 39 | 31 | 1 415 | 1 335 | 101 560 | 13 | 67 |

| 2010 | 531 | 472 | 35 413 | 45 | 14 | 1 416 | 1 336 | 124 291 | 13 | 67 |

| 2011 | 403 | 353 | 24 994 | 44 | 6 | 2 108 | 1 449 | 127 723 | 232 | 427 |

| 2012 | 565 | 495 | 36 830 | 56 | 14 | 3 070 | 2 110 | 198 991 | 338 | 622 |

| 2013 | 473 | 398 | 37 854 | 70 | 5 | 3 332 | 2 290 | 218 051 | 366 | 676 |

| 2014 | 680 | 640 | 55 667 | 16 | 24 | 2 814 | 2 345 | 215 069 | 384 | 85 |

| 2015 | 932 | 821 | 61 695 | 93 | 18 | 4 859 | 4 305 | 399 453 | 323 | 231 |

| 2016 | 591 | 499 | 29 618 | 79 | 13 | 1 460 | 1 169 | 106 167 | 127 | 164 |

| Total | 11 238 | 9 755 | 844 853 | 848 | 635 | 29 001 | 24 379 | 2 222 251 | 1 878 | 2 744 |

| Mean ± Std Dev | 281.0 ± 200.0 | 243.9 ± 179.8 | 21 121.3 ± 13 911.2 | 21.20 ± 22.7 | 15.9 ± 13.4 | 1 035.8 ± 1 249.2 | 870.7 ± 1 018.6 | 79 366.1 ± 93 792.3 | 67.1 ± 128.4 | 98.0 ± 180.0 |

Nesting, predation, and poaching trends: For both nesting beaches, a positive and significant correlation was observed between the number of registered nests and time (rho = 0.850, P ≤ 0.01 for SPC, rho = 0.677, P ≤ 0.01 for PC, Table 2) and between predated nests and time (rho = 0.454, P = 0.003 for SPC, rho = 0.789, P ≤ 0.01 for PC, Table 2). The average number of poached nests at SPC was 15.9 ± 13.4 nests/year (Table 1). A positive and significant correlation between the number of poached nests (98.0 ± 180.0 nests/year) and time was observed (rho = 0.673, P = 0.01; Table 2) for only PC.

Table 2 Correlation of registered, predated and poached nests and the course of time (years) for Santuario Playa Ceuta (SPC) during 1976-2016 and for Playa Caimanero (PC) during 1989-2016

| Santuario Playa Ceuta | Playa Caimanero | ||||||

| Registered nest | Predated nests | Poached nests | Registered nest | Predated nests | Poached nests | ||

| Years | rho Spearman | 0.850 | 0.454 | 0.145 | 0.677 | 0.789 | 0.673 |

| P value | ≤ 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.372 | ≤ 0.01 | ≤ 0.01 | ≤ 0.01 | |

rho = Spearman’s correlation coefficient, P < 0.05.

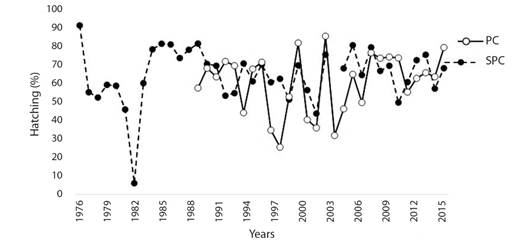

Hatching success: HS showed great variability over the years at both beaches. However, since 2009, these oscillations stabilized for both beaches (Fig. 2). HS percentages of 65.09 ± 14.72 % for SPC and 60.72 ± 16.39 % for PC were estimated, and these values were not statistically significant between beaches (Mann-Whitney U = 486, P = 0.360).

Fig. 2 Annual hatching success of the olive ridley turtle at Santuario Playa Ceuta and Playa Caimanero, Sinaloa, Mexico. SPC: Santuario Playa Ceuta; PC: Playa Caimanero.

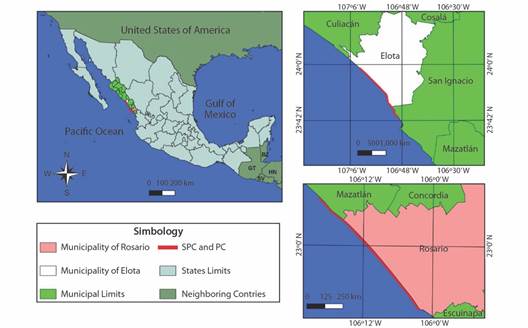

Prospective nesting in 2045: According to the annual data analyzed, a predictive time-series model with Brown exponential smoothing was constructed; in both cases, the residual values were independent (DF= 17, Ljung-Box Q (18) = 9.492, P= 0.924 for SPC; DF= 17, Ljung-Box Q (18) = 6.498, P= 0.989 for PC). The observed values have annual variations but suggest a positive trend, as shown by the adjusted values for both beaches (Fig. 3A, Fig. 3B). From a stationary R2 of 0.649, the prediction for 2045 is 1 733 [-215, 3 681] nests at SPC (Fig. 3A) and 7 718 [-2 435, 17 871] nests at PC, with a stationary R2 of 0.632 (Fig. 3B).

Discussion

Due to the management and conservation efforts of PROTORMAR-UAS for the olive ridley sea turtle in Northwestern Mexico, an increase in the abundance of nests and eggs collected at both biological stations was observed from the start of operation until the last data point. According to the correlation analysis, there was an increase in the number of nests throughout the study period at both beaches. These increases may be due to different causes or even a combination of several factors, which together could influence the observed positive trend of the increase in nests (rho= 0.850 and rho= 0.677). These values coincide with that reported in Playa La Flor in Nicaragua, where a positive trend was observed over 8 years of monitoring (Honarvar et al., 2016). Increases in the numbers of nests were recorded at both nesting beaches, which have similar lengths (≈ 37 km), and the projection for 2045 was positive according to the time-series model with Brown exponential smoothing. At both nesting beaches, monitoring and tours were standardized in 1992; in both cases, initial tours were by foot and later by quad bike, depending on the budget, available staff, and number of volunteers, as well as weather conditions. The current results are in accordance with those reported by Anzanza-Ricardo et al. (2015), who noted that in sea turtle conservation programs, resource management is crucial to achieve an adequate cost-benefit balance, and Hart et al. (2018), who stated that an increase in and consolidation of conservation and monitoring activities will result in an increase in the number of nests. However, monitoring and conservation program evaluation continue to be a challenge due to complications that can occur during data collection and difficulty in obtaining financial incentives to promote community participation that promote positive attitudes towards conservation and consistency in the collection of information (Godley et al., 2020).

It is important to emphasize that although there have been increases in the numbers of nests on both beaches after effort standardization, there has been a larger increase at PC, with more than 1 000 nests, which is approximately 3-fold the number of nests than at SPC after 2005. The conditions of both beaches are quite different; SPC is a very spatiotemporally dynamic beach in its granulometry and slope (Sosa-Cornejo et al., 2019), while the conditions at PC are more static. In addition, SPC is in the Nearctic zone, and PC is in the Neotropical zone. The El Verde Camacho nesting beach, also in Sinaloa, has been considered the Northern limit of nesting of the olive ridley turtle in the Mexican Pacific (Ríos-Olmeda, 2005). However, SPC is located at a more Northern latitude, and PC, which is South of El Verde Camacho, has registered a larger number of nests in the last 15 years than the El Verde Camacho nesting site (Contreras-Aguilar, pers. comm.). Genetic analysis of organisms inhabiting SPC indicated that this rockery has moderate genetic diversity that is very similar (h= 0.6) to that reported by Briseño-Dueñas (1998) for El Verde Camacho (Campista-León et al., 2019); therefore, the importance of monitoring and conserving SPC and the need for more studies at PC are highlighted due to the increasing numbers of nests. In addition, climatic variations, such as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), can influence the reproductive success of sea turtles (Santidrián Tomillo et al., 2020); these climatic variations could have no effect or a moderate effect on olive ridley turtle nesting (Ariano-Sánchez et al., 2020; Santidrián Tomillo et al., 2020). This was observed during the extreme El Niño 2015-2016 event, which resulted in decreases in the numbers of nests on both beaches.

Additional factors that may have also influenced the increases in the number of nests are the age at sexual maturity (approximately 13 years [8-18 years]) of age (Márquez, 1996; Zug et al., 2006), the total and permanent ban of the capture of all species of sea turtles in waters under Mexican jurisdiction (DOF, 1990) and the use of sea turtle excluders since 1996 (DOF, 1996). Increases in nesting activity have been reported for other species of sea turtles, such as green and loggerhead turtles (Moncada et al., 2014). Whether the main cause of the increase in the number of nests is increased monitoring effort, the total and permanent capture ban in 1990, spatial changes in the nesting behavior of the olive ridley sea turtle as a result of adaptation to environmental factors, or a combination of these and other factors remains unknown; therefore, it is necessary to carry out additional studies and continue monitoring the abundance of nests in this region. Nesting of olive ridley sea turtles, although sporadic, has been reported in the upper Gulf of California in San Carlos, El Desemboque, and Puerto Peñasco, Sonora (Seminoff & Nichols, 2007). A record number of olive ridley sea turtle hatchlings (2 241) was recently reported in Desemboque, Sonora, which is located at a very Northern latitude for olive ridley nesting, where conservation has been performed for more than 20 years (Arellano, 2020).

Although olive ridley turtles are the most abundant sea turtles in the world, information on olive ridley turtles is scarce compared to that for other species (Abreu-Grobois & Plotkin, 2008). According to the IUCN red list, global olive ridley populations are decreasing, with a total decrease between 30 % and 50 %, and it is not known whether this reduction has stopped or if it is reversible (Abreu-Grobois & Plotkin, 2008). However, at the arribada beach, La Flor de Nicaragua, a drastic increase in the number of nests was reported from 1998 to 2006 (Honarvar et al., 2016), and at Playa Escobilla, the most important arribada beach in Mexico, sustained recovery was reported (1973-2010) (CONANP, 2011). However, considering the wide pantropical nesting habits of the olive ridley turtle, evaluations on solitary beaches are scarce. In the Mexican Pacific South of our study area, in the states of Jalisco and Nayarit, increases in the numbers of nests were reported and attributed to conservation programs that had been implemented for 29 years (Hart et al., 2018). For a beach in Guatemala, a sustained increase in the number of nests over the course of 16 years was reported (Ariano-Sánchez et al., 2020), while for the Pacific beaches of Costa Rica, clear trends have not been reported (James & Melero, 2015; Viejobueno Muñoz & Arauz, 2015). For a beach in Brazil, an increase in the number of olive ridley nests was reported in 10 out of 11 years (da Silva et al., 2007).

Similar HS was recorded at both beaches (65.09 and 60.72 % for SPC and PC, respectively); these values were close to those reported by Bárcenas-Ibarra et al. (2015) for El Verde Camacho (58 %). Other studies have reported a HS rate ranging between 75 and 85 % (Table 3). However, these studies were conducted in more Southern latitudes of the Mexican Pacific, except for the study by da Silva et al. (2007). A lower HS rate was reported for olive ridley turtles than for other species, such as hawksbill and green sea turtles (Bárcenas-Ibarra et al., 2015); this discrepancy could be because for other species, incubation regularly occurs in situ, while for the olive ridley turtle, nests are artificially incubated or relocated to hatcheries, which affects mortality and HS (Mrosovsky, 1982). However, at an olive ridley nesting beach in Costa Rica, Viejobueno Muñoz and Arauz (2015) reported a HS rate of 61.38 % for in situ nests, while the HS rate for nests relocated to a hatchery was 77.9 % (Table 3). It is necessary to compare the HS rates of in situ and relocated nests to guide management decisions, although predation and poaching may limit these analyses for both nesting beaches. Another factor influencing the incidence of HS is temperature, as it has been shown that in some cases, temperature exceeds the pivotal point of embryonic mortality (Rafferty & Reina, 2014; Sandoval, 2012). In addition, it is important to consider different management-related factors, such as losses that occur during monitoring phases on the beaches since these also affect HS but are rarely evaluated.

Table 3 Hatching success at different nesting beaches of olive ridley turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea), including Santuario Playa Ceuta and Playa Caimanero

| Author (s) | Year | Country or region | Hatching success (%) |

| Galván | 1991 | Jalisco, México | 78.3 |

| Cupul-Magaña & Aranda-Mena | 2005 | Jalisco, México | 77.8 |

| da Silva et al. | 2007 | Sergipe and Bahía, Brasil | 78.7 |

| Bárcenas-Ibarra & Maldonado Gasca | 2009 | Nayarit, México | 79.4 |

| Barrientos-Muñoz et al. | 2014 | Playa El Valle, Colombia | 81.1 |

| Bárcenas-Ibarra et al. | 2015 | Sinaloa, México. | 58 |

| James & Melero | 2015 | Península de Osa, Costa Rica | 79.2 |

| Viejobueno Muñoz & Arauz | 2015 | Punta Banco, Costa Rica | 77.9 |

| Carretero-Morales et al. | 2018 | Jalisco, México | 79.7 |

| Hart et al. | 2018 | Nayarit, Jalisco, México | 85.4 |

| This study SPC | 2016 | Sinaloa, México | 65.08 |

| This study PC | 2016 | Sinaloa, México | 60.72 |

SPC: Santuario Playa Ceuta; PC: Playa Caimanero.

Regarding the number of predated and poached nests, both indicators were higher at PC than at SPC. These results are not surprising, as PC has a higher annual density of nests than SPC, resulting in a greater availability of eggs for predators. Leighton et al. (2010) suggested that the probability of nests being predated or poached increases over time, which was in accordance with the results of the regression analysis for PC. The rate of poaching of eggs at SPC did not increase over time; this is likely because this beach is legally protected and far from urban settlements. PC is not legally protected, and coastal communities are present along the beach, which facilitates poaching even though it is prohibited. Moreover, protection of the beach has not been increased due to the lack of economic resources, and protection status is an important variable for monitoring (García et al. 2003). On Venezuela’s nesting beaches, both predation and poaching rates were reduced over 10 years of conservation (2003-2012) (Balladares & Dubois, 2014). However, each nesting beach and its surrounding environment have very peculiar characteristics. Coyotes (Canis latrans) are the most common opportunistic predators of sea turtles in arid areas of Mexico, and at both SPC and PC, the predation of eggs by coyotes is common; in recent years, the population of this predator has been increasing (Álvarez-Castañeda, 2000; Méndez-Rodríguez & Álvarez-Castañeda, 2016). At SPC, in addition to coyotes, the presence of new predators such as raccoons and badgers has been reported in recent years (2013-2016), and this may be an explanation for the increase in predation. The presence of these predators could be related to the modification of habitats for shrimp farming and agriculture.

Monitoring and conservation efforts for the olive ridley turtle by the PROTORMAR-UAS program have indicated that there has been an increase in the number of nests at both beaches since the establishment of the camps to the present day. We suggest that PC, which is located on the latitudinal limit of olive ridley nesting, be designated as a legally protected nesting area, given the need for resources for the operation of the camp to ensure that nest numbers continue to increase and address predation and poaching. In addition, it is necessary to carry out additional studies related to the sex ratio of neonates, management and conservation program success, and mortality and congenital malformation incidence in this species. With this information and data from assessments of nesting trends, it will be possible to identify indicators and form a clearer picture of the situation the olive ridley sea turtle with regard to management and conservation programs to guide appropriate decisions regarding these programs.

Ethical statement: the authors declare that they all agree with this publication and made significant contributions; that there is no conflict of interest of any kind; and that we followed all pertinent ethical and legal procedures and requirements. All financial sources are fully and clearly stated in the acknowledgements section. A signed document has been filed in the journal archives.

uBio

uBio