Introduction

The Sipuncula is a small group of unsegmented vermiform protostomes (Murina, 1984; Cutler, 1994). Their most noticeable feature is a body divided into a retractable introvert and trunk, and they are commonly known as “peanut worms”, owing to the shape of their bodies when contracted (Cutler, 1994). Recent phylogenetic hypotheses have suggested their placement within Annelida, based entirely on molecular analyses (Staton, 2003; Struck et al., 2007; Dordel, Fisse, Purschke, & Struck, 2010; Lemer et al., 2016), although this proposal conflicts with the traditional definitions of both taxa (Boyle & Rice, 2018) and has not yet been fully accepted (Saiz, 2018).

Gibbs & Cutler (1987) proposed a taxonomic classification based on their previous morphology-based phylogenetic analysis (Cutler & Gibbs, 1985). Kawauchi, Sharma, & Giribet (2012) conducted a multi-gene phylogenetic analysis, which required the erection of two new families (Siphonosomatidae and Antillesomatidae) and the synonymy of Themistidae and Phascolionidae with Golfingiidae. This classification was reevaluated using transcriptomics by Lemer et al. (2016), but has not yet replaced the traditional classification of Gibbs & Cutler (1987) on the World Sipuncula Database (Saiz, 2018).

To date, the family Antillesomatidae contains a single species, Antillesoma antillarum (Grube & Öersted in Grube, 1858). The type locality of this species is Puntarenas, Costa Rica and Saint Croix, Virgin Islands (Grube, 1858). As the type material was not clearly established, Cutler & Cutler (1983) revised material from different tropical and subtropical localities, obtaining a long list of synonyms, redescribing the species based on material from Barbados and Saint Croix, and concluding that A. antillarum is widely distributed in the coastal zones of tropical and subtropical localities of the world. Unfortunately, the new type locality was also not specified (Cutler & Cutler, 1983: 183).

Some relatively recent works on Sipuncula used molecular tools to solve problems of taxonomic identification where morphology offered limited resolution (Staton & Rice, 1999; Kawauchi & Giribet, 2010; Schulze, Maiorova, Timm, & Rice, 2012; Kawauchi & Giribet, 2014; Johnson, Sanders, Maiorova, & Schulze, 2016). The wide distribution of several species (see Cutler 1994) has been questioned by these studies. Therefore, the objective of this study is to demonstrate the differences between the amphiamerican populations of Antillesoma by means of the analysis of molecular and morphological characters. In this work, the genetic distances among populations of Antillesoma are calculated and compared to reference values in other genera. Finally, a new species of Antillesoma from the Mexican Pacific is described.

Material and methods

Specimens regarded as A. antillarum were revised in two collections: Colección Científica de Invertebrados Marinos (OAX-CC-249-11) at Laboratorio de Sistemática de Invertebrados Marinos (LABSIM), Universidad del Mar, and the Colección de Referencia del Bentos Costero (ECO-CH-B) at El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR, Chetumal). The external anatomy was analyzed with the aid of a Carl Zeiss stereomicroscope, and some specimens were dissected in order to describe internal traits, using the identification key of Cutler (1994). A t-Student test was used to compare mean size of the trunk between the specimens from the Caribbean and Pacific.

Specimens were extracted from coral rubble from the intertidal zone of Panteón Beach, Puerto Ángel, Oaxaca (15°39’49” N, 96°29’39” W), and retractor muscles were isolated in accordance with Kawauchi & Giribet (2010). The tissues were fixed in 96% ethanol and total DNA was extracted from two specimens using the Animal and Fungi DNA Preparation Kit of Jena Bioscience (Jena, Germany), following the instructions of the manufacturer. The cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI) was amplified in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the primers LCO1490-HCO2198 (Folmer, Black, Hoeh, Lutz, & Vrijenhoek, 1994). The 15 μl PCR reaction volumes were composed of 9.4 μl distilled water, 3 μl buffer [5x], 0.1 μl MgCl [50 mM], 0.1 μl Taq [5 μ/μl], 0.2 of each primer (100 pM), and 2 μl DNA. Thermal cycling consisted in an initial denaturing at 94 °C (5 min), followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C (45 s), 46 °C (45 s) and 72 °C (45 s), with a final extension at 72 °C (7 min). PCR products were viewed in a 1 % agarose gel. DNA extraction and Sanger sequencing were performed at the Laboratorio Nacional de Biodiversidad (LANABIO), Instituto de Biología, UNAM. Sequences were edited with Geneious Pro v. 5.1.7 (Biomatters Ltd., New Zealand), checking for ambiguities and reading errors. GenBank accession numbers for our new sequences are MK036430 and MK036431. Four A. antillarum sequences were retrieved from GenBank and added to our dataset, three of them from the Western Atlantic (accession numbers: DQ300102, AY161134, GU230172) and the fourth from the Indo-Pacific (accession number: JN865120). Phascolosoma perlucens Baird, 1868 (accession number: GU190304) was included as an outgroup based on previous analyses. Sequences were aligned manually in Bioedit v. 7 (Hall, 1999). Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic reconstruction was performed under the General Time-Reversible (GTR) model as suggested by PhyML 3.0 (Guindon et al. 2010), following the Akaike Information Criterion. Genetic distances were calculated among the Antillesoma lineages in MEGA7.0.26 (Kumar, Stecher, & Tamura, 2016) with the Kimura two-Parameter (Kimura-2P). For comparison, genetic distances were calculated between P. perlucens, Phascolosoma agassizii Keferstein, 1866 and Sipunculus nudus Linnaeus, 1766, made available by Kawauchi & Giribet (2010), Schulze et al. (2012) and Kawauchi & Giribet (2014), respectively.

Results

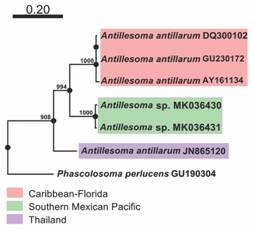

Molecular analyses: The dataset, including our two new COI sequences, had an alignment length of 541 bp. The six analyzed sequences revealed three distinct lineages (Fig. 1). The group of the Southern Mexican Pacific is clearly separated from the others and it is described as new species in the present study. The genetic distance among the Caribbean-Florida and Mexican Pacific specimens was 0.21, while the distance between the Florida and Barbados sequences was 0.008 (Table 1A-B). For comparison, the recalculated genetic distances among the lineages of P. agassizii, P. perlucens and S. nudus are shown in Table 1C-E.

Fig. 1 Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree under the GTR model obtained in PhyML 3.0, with a bootstrap of 1 000 replicates and Phascolosoma perlucens as the outgroup.

Table 1 Pairwise genetic distances among sipunculan lineages recalculated with Kimura-2P. Standard error is shown in bold

| A. Among Antillesoma lineages | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| 1. A. mexicanum sp. nov. from Mexican Pacific | 0.033 | 0.031 | |||

| 2. A. antillarum from Caribbean-Florida | 0.210 | 0.033 | |||

| 3. A. antillarum from Thailand | 0.181 | 0.189 | |||

| B. Among A. antillarum lineages, separating Florida and Caribbean | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1. A. mexicanum sp. nov. from Mexican Pacific | 0.035 | 0.033 | 0.031 | ||

| 2. A. antillarum from Florida | 0.211 | 0.006 | 0.033 | ||

| 3. A. antillarum from Caribbean | 0.199 | 0.008 | 0.032 | ||

| 4. A. antillarum from Thailand | 0.181 | 0.200 | 0.188 | ||

| C. Among P. agassizii lineages, (Schulze et al., 2012) | |||||

| 1 | 2 | ||||

| 1. NE Pacific | 0.023 | ||||

| 2. Sea of Japan | 0.260 | ||||

| D. Among P. perlucens lineages (Kawauchi & Giribet, 2010) | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1. Costa Rica (Pacific Ocean) | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.023 | 0.023 | |

| 2. Florida | 0.121 | 0.000 | 0.023 | 0.022 | |

| 3. Caribbean | 0.120 | 0.001 | 0.023 | 0.022 | |

| 4. South Africa | 0.200 | 0.201 | 0.201 | 0.018 | |

| 5. Thailand | 0.244 | 0.235 | 0.235 | 0.185 | |

| E. Among S. nudus lineages (Kawauchi & Giribet, 2014) | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1. Panama (Pacific Ocean) | 0.023 | 0.024 | 0.021 | ||

| 2. China | 0.261 | 0.022 | 0.021 | ||

| 3. France-Spain | 0.254 | 0.253 | 0.022 | ||

| 4. Florida | 0.253 | 0.237 | 0.240 | ||

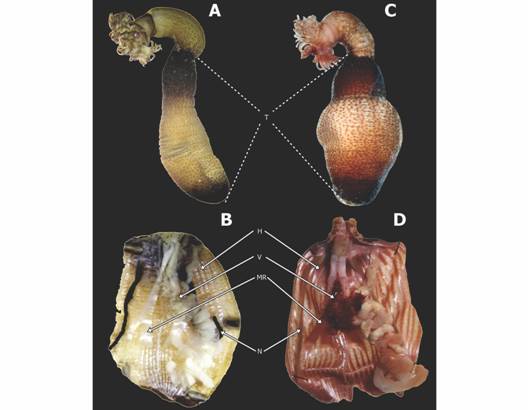

Morphological analyses: Specimens of A. antillarum from the southern Mexican Pacific (Fig. 2A-B) and from the Mexican Caribbean (Fig. 2C-D) are different in the trunk size (t-student test, p < 0.01). The average in the Mexican Pacific population is 7 mm (n= 40, r= 2-15 mm, µ= 6.90, SD= 1.03), while in the Mexican Caribbean it is 18 mm (n= 51, r= 9-32 mm, µ= 18.01, SD= 5.90).

Fig. 2 Antillesoma mexicanum sp. nov. A. Specimen from Oaxaca, México. B. Internal morphology. Antillesoma antillarum. C. Specimen from Quintana Roo, México. D. Internal morphology. Abbreviations: H, muscle bundles; MR, retractor muscles; N, nephridia; T, trunk; V, villi.

SYSTEMATIC ACCOUNT

Phylum Sipuncula Rafinesque, 1884

Family Antillesomatidae Kawauchi,

Sharma & Giribet, 2012

Genus Antillesoma

(Stephen & Edmonds, 1972)

Antillesoma mexicanum sp. nov.

(Figs. 2A-B)

Type locality: Panteón Beach, Puerto Ángel, Oaxaca, Mexico; 2 m, in coral rubble, March 30, 2017, collector Julio D. Gómez-Vásquez.

Holotype: UMAR-SIPU 108. paratypes: UMAR-SIPU 018, 63 specimens. ECOSUR-S0288, 14 specimens. UNAM-CNINV 145, four specimens.

Additional material: 110 specimens (spec). Guerrero: UMAR-SIPU 004, four spec. (Ixtapa Island, coral debris, September 19, 2007, coll. Socorro García-Madrigal). UMAR-SIPU 013, three spec. (Coral Beach, Ixtapa Island, September 19, 2007, coll. Socorro García-Madrigal); Oaxaca: UMAR-SIPU 109, one spec. (Arrocito Beach, Huatulco, coral debris, May 23, 2000); UMAR-SIPU 003, three spec. (Camarón Beach, Zipolite, coral debris, 2 m, November 16, 2016, coll. ISM); UMAR-SIPU 005, 12 spec. (Estacahuite Beach, Puerto Ángel, coral debris, September 10, 2005); UMAR-SIPU 006, four spec. (Camarón Beach, Zipolite, coral debris, April 6, 2013, coll. Víctor Alvarado); UMAR-SIPU 007, five spec. (San Agustín Bay, Huatulco, rocks, 5 m, October 24, 2014); UMAR-SIPU 008, 16 spec. (Tijera Beach, Pochutla, coral rock, 4 m, April 30, 2005, coll. JRBZ); UMAR-SIPU 009, 23 spec. (Panteón Beach, Puerto Ángel, coral debris, April 16, 2008, coll. Luis Carrera-Parra); UMAR-SIPU 010, one spec. (San Agustín Bay, Huatulco, coral debris, November 17, 2016, coll. Julio Gómez-Vásquez); UMAR-SIPU 014, six spec. (Estacahuite Beach, dead coral, September 10, 2005); UMAR-SIPU 015, one spec. (Salchi Beach, March 26, 2010); UMAR-SIPU 016, two spec. (Puerto Ángel, 0.5 m, in pier piles, June 10, 2011, coll. Raúl Ramírez); UMAR-SIPU 017, one spec. (Camarón Beach, dead coral, April 6, 2013, coll. Rodrigo Xavier); UMAR-SIPU 019, one spec. (Bocabarra Chacahua, in artificial monticule, without date); Chiapas: UMAR-SIPU 020, one spec. (Pier of Puerto Chiapas, 3 m, in rocks with oyster, September 20, 2011, coll. JRBZ). ECOSUR-S0288, 14 spec. (Puerto Abrigo, Huatulco, in rocks, May 22, 2000, coll. Sergio Salazar-Vallejo); ECOSUR-S0289, nine spec. (Puerto Abrigo, Huatulco, in mollusk, May 22, 2000, coll. Sergio Salazar-Vallejo); ECOSUR-S0290, three spec. (Panteón Beach, Puerto Ángel, in coralline rock, 1.5 m, April, 16, 2008, coll. Luis Carrera-Parra).

Comparative material: Antillesoma antillarum, 30 specimens. Quintana Roo: ECOSUR-S0002, one spec. (Punta Herradura, Xauayxol, 4 m, in coralline rock, October 28, 1997, coll. Luis Carrera-Parra & Sergio Salazar-Vallejo). ECOSUR-S0004, 29 spec. (Mahahual Beach, 2 m, coral debris, March 4, 1998, coll. Sergio Salazar-Vallejo & Luis Carrera-Parra).

Description: Tentacles encircling the nuchal organ, leaving the mouth free; tentacle shape digitiform, almost all of the same size, with a coloration pattern of dark transverse patches on most tentacles. Distinctive collar between the tentacles and the introvert. Relaxed trunk length 12 mm, dark brown color, with dark color on the anterior and posterior trunk. Middle region of the trunk remains light-colored with three types of papillae: larger ones dark-brown in color on the anterior and posterior trunk, occupying 1/3 of the trunk; small conical ones, dispersed in the introvert region, and small and poorly defined ones in the middle region of the trunk (Fig. 2A). Lacks hooks. Two pairs of retractor muscles. Longitudinal musculature is divided into numerous anastomosing bundles. Numerous villi in the contractile vessel. A pair of unilobed dark nephridia occupying 75 % of the trunk, open posteriorly to the anus. Spindle muscle attached posteriorly (Fig. 2B).

Habitat: Intertidal to subtidal (5 m); in coral rubble, rocks, and pier piles, associated to burrowing invertebrates.

Distribution: Southern Mexican Pacific, from Ixtapa, Guerrero, to Chiapas.

Remarks: The sipunculan worm A. antillarum, the geminate species of A. mexicanum sp. nov., was described by Grube & Örsted, 1858InGrube (1858). In the revision of Cutler & Cutler (1983) a specimen from Puntarenas, Costa Rica, was revised. It is mentioned that the type material, from other localities was lost and the species was re-described with specimens from Saint Croix and Barbados, without clarifying the neotype and the new type locality.

Antillesoma mexicanum sp. nov. differs from A. antillarum in its pigmentation pattern, being darker brown and having dark trunk papillae scattered in less than 1/3 of the trunk. Antillesoma antillarum has a fainter dark, pinkish pigmentation, and the dark-pink trunk papillae are scattered across almost 1/2 of the trunk. Specimens of this new species are found in the rest of the Mexican Pacific (Julio D. Gómez-Vásquez com. pers. 2018)

Etymology: Named after the Pacific Mexican littoral, where its geographic distribution has been corroborated.

Discussion

According to the review of Cutler & Cutler (1983), A. antillarum is widely distributed in all tropical and subtropical regions, and historically the species has been recorded on both coasts of Tropical America. However, the dispersal of the species from the Caribbean to the Pacific or viceversa through the Panama Canal is unlikely, as it would imply a high larval or adult tolerance to the salinity changes throughout the Panama Canal (Jaramillo, Hoorn, Perrigo, & Antonelli, 2018); there are no records of sipunculans able to support these conditions (Cutler, 1994). In contrast, our results suggest that the pre-Pleistocene American population (2-3 million years ago) of A. antillarum was separated from A. mexicanum sp. nov., when the Central American Isthmus was formed, which represented a barrier to gene flow among populations of benthic invertebrates that are not part of the burrowing fauna (see Lessios, 2008). Likewise, larval dispersal from the Indo-Pacific to the Mexican Pacific is discarded due to the evidence provided by the genetic distance between the samples from Mexico and Thailand.

Kawauchi & Giribet (2010) found great molecular divergence between specimens of P. perlucens from the Pacific of Costa Rica and the Western Atlantic, but their similar hook morphology could also indicate allopatric speciation caused by the rise of the Central American Isthmus. Likewise, the authors mentioned that it should not be ruled out that P. perlucens of the Caribbean and the Pacific of Costa Rica are cryptic or geminate species. Because the genus Antillesoma does not have hooks, we suggest that other characters such as trunk length, papillae patterns and coloration could be useful to discern the species. For comparison, the genetic distance between the populations of P. perlucens from both coasts of tropical America was 0.12, while in this work, between A. mexicanum sp. nov. and A. antillarum was 0.21, which indicates a considerable differentiation (Kawauchi & Giribet, 2010).

Schulze et al. (2012) considered that the re-examination of the morphology of cosmopolitan sipunculans would not be enough to differentiate species, and thus, they suggest the combination of molecular and morphological data, incorporating information of intraspecific variation for the correct delimitation of the species. These authors analyzed two populations of P. agassizii from the Sea of Japan and the Northeast Pacific, obtaining a genetic distance of 0.26 between the populations; this work was the first evidence that sipunculan larvae are not able to disperse across the Pacific Ocean.

Kawauchi & Giribet (2014) examined S. nudus from worldwide disparate localities and the genetic distances found are in a range of 0.23 to 0.26. Between the population of S. nudus from Pacific of Panama and the population of Florida, the genetic distance was 0.25. Similarly, we obtained a distance of 0.21 between Antillesoma from both sides of Tropical America.

These studies on population genetics in sipunculans have revealed a significant genetic differentiation between geographically remote populations, species complexes and distinct genetic lineages. In this study, different lineages were also found, naming the lineage from the Mexican Pacific as A. mexicanum sp. nov., completing the taxonomic work.

The genetic distance between the Antillesoma lineages of both coasts of tropical America was 0.21, which, together with the morphological evidence, allows to identify the lineages of both coasts as A. antillarum from the Caribbean and A. mexicanum sp. nov.

Ethical statement: authors declare that they all agree with this publication and made significant contributions; that there is no conflict of interest of any kind; and that we followed all pertinent ethical and legal procedures and requirements. All financial sources are fully and clearly stated in the acknowledgements section. A signed document has been filed in the journal archives.

uBio

uBio