The first records on earthworms in Argentina date from the 19th century (Michaelsen, 1900; Cognetti de Martiis, 1901), and were primarily of systematic and zoogeographical nature. These studies contributed significantly to knowledge of terrestrial oligochaetes. During the second half of the 20th century, the Brazilian zoologist Gilberto Righi, the Swedish researcher Per-Olf Ljungström and the Argentinian taxonomist Catalina de Mischis were distinguished by their contributions on the oligoquetofauna of Argentina. The studies on earthworms in the province Santa Fe in the 1970’s produced information on the taxonomy, distribution and ecology of earthworms (Ljungström, 1971; Ljungström & Emiliani, 1971; Ljungström, Orellana, & Priano, 1973; Ljungström, Emiliani, & Righi, 1975; Righi, 1979). Such works added interesting contributions on the relevance of earthworms as a natural resource. In this regard, the study “Notas sobre los oligoquetos (lombrices de tierra) argentinos” by Ljungström et al. (1975), consisted of the most complete research work on oligoquetofauna for Argentina, in particular for Santa Fe province.

The last systematic review of earthworms for Argentina was performed by Mischis (2007), who recorded 25 species for Santa Fe province: three species of Glossoscolecidae (Glossoscolex uruguayensis uruguayensis, Glossoscolex uruguayensis ljungstromi), ten species of Ocnerodrilidae (Belladrilus emiliani, Eukerria asuncionis, Eukerria eiseniana, Eukerria halophila, Eukerria saltensis, Eukerria santafesina, Eukerria stagnalis, Eukerria subandina, Ilyogenia comondui, Ocnerodrilus occidentalis), four species of Acanthodrilidae (Dichogaster bolaui, Dichogaster saliens, Microscolex dubius, Microscolex phosphoreus) and seven species of Lumbricidae (Aporrectodea caliginosa, Aporrectodea rosea, Aporrectodea trapezoides, Bimastos parvus, Eisenia fetida, Eiseniella tetraedra tetraedra, Octolasion tyrtaeum). The South American family Ocnerodrilidae was the one that displayed the highest number of species, followed by the exotic family Lumbricidae. This review was based on the previous work of Ljungström et al. (1975) about of oligoquetofauna for Santa Fe.

Forty years later after the publication of the paper of Ljungström et al. (1975), the studies on earthworms in province Santa Fe are scarce (Masin, Rodríguez & Maitre, 2011; Maitre, Rodríguez, Masin, & Ricardo, 2012; Masin et al., 2017).

The aim of the work is to provide updated information on the richness and territorial distribution of the earthworm species in Santa Fe.

Material and methods

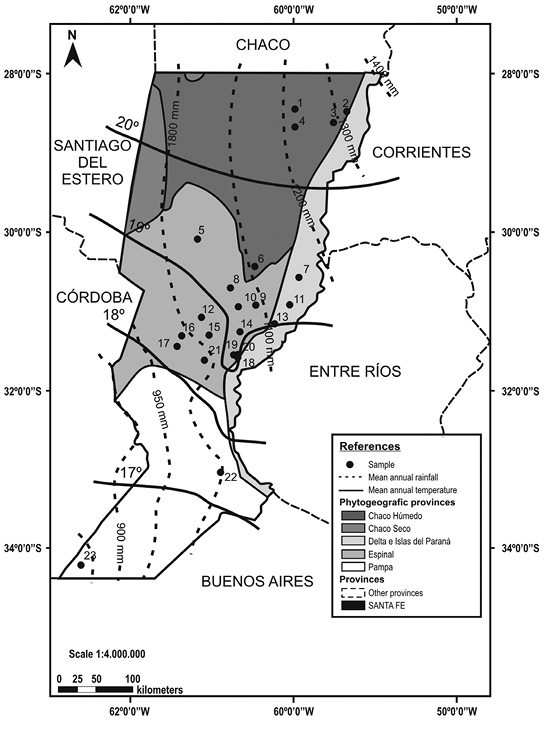

Study area: The study was conducted in the province of Santa Fe (Figure 1), which has an area of 133 007 km2 and is located in the east-central region of the Republic Argentina, in the south of the American continent. Its north-south axis is 720 km long, and the east-west axis is 380 km long. It is divided into 19 districts and it is an extensive plain that ranges from 10 to 125 masl (Biasatti et al., 2016).

Figure 1 Sites sampled in Santa Fe during 2012-2015 (Modified from Arzamendia & Giraudo, 2004). References: 1= Los Tábanos; 2 = Villa Ocampo; 3= El Sombrerito; 4= Tartagal; 5= La Cabral; 6= Colonia Silva;7= San Javier; 8= San Justo; 9= Naré; 10= Videla; 11= Helvecia; 12= Sarmiento; 13= Cayastá; 14= Laguna Paiva; 15= Grutly; 16= Rafaela; 17= Susana; 18= Monte Vera; 19= Recreo; 20= Ángel Gallardo; 21= San Jerónimo del Sauce; 22= Zavalla; 23= Rufino.

The climate of Santa Fe has two gradients, one thermal from north to south, and another hydric from east to west. Because of its thermal regime, the climate can be defined as temperate without cold season in the south and temperate and warm in the north (average temperatures of 21 °C and precipitations between 850 and more than 1200 mm annually). For the hydric regime, it varies from humid to subhumid from east to west (Lewis & Collantes, 1974).

The main types of vegetation in Santa Fe are included in four phytogeographic provinces and five subdivisions (Cabrera, 1976; Prado, 1993; Dinerstein et al., 1995; Burkart, Bárbaro, Sánchez, & Gómez, 1999) (Figure 1):

1. Chaqueña province with two areas: 1A) Chaco Seco: located in the northwest and characterized by water deficit, with predominance of xerophile forests. 1B) Chaco Húmedo: located in the northeast and north central, has higher mean annual rainfall (above 1000 mm) and its vegetation includes humid subtropical deciduous forests, savannahs of palm trees and grasslands with various types of wetlands.

2. Espinal province, in the centre, is characterized by the presence of low xerophile forest.

3. Valle de Inundación del Río Paraná province, its main vegetation types are subtropical wet forest, gallery forest, various types of flooded savannas and wetlands (rivers, streams, ponds, marshes and estuaries).

4. Pampeana province in the south is mainly is composed of different types of grasslands.

Collection and identification of earthworms: Earthworms were obtained by field sampling carried out between 2012 and 2015 in 23 sites (Figure 1), located in 11 out of the 19 districts of the province. Earthworms were collected of various environments including agricultural systems (under various tillage management practices), livestock systems, gardens, native grasslands and native forest.

The methodology used was TSBF (Tropical Soil Biology and Fertility) (Anderson & Ingram, 1993). In each site a total of 40 monoliths were collected during two seasonal instances (20 in autumn and 20 in spring). Each monolith (30 x 30 x 30 cm) was distanced from each other by 15 m along a transect. The conservation of specimens was done with 4 % formalin solution, and identification was performed according to Mischis (1991), Reynolds (1996) and Blakemore (2005). Moreover, each species was assigned to an ecological group (Bouché, 1977).

The taxonomic, zoogeographical and ecological update of the oligoquetofauna presented included both data provided by Ljungström et al. (1975) as well as de novo data of a Doctoral Thesis (Masin, 2017). The study of Ljungström and collaborators provides a base and reference record on oligoquetofauna of Santa Fe, what allows to interpret and compare in a general way with the information of the current survey.

Statistical analysis: The percentage of complementarity was analyzed measuring the degree of difference in composition of species between different communities (Colwell & Coddington, 1994). Complementarity varies from zero (identical species composition) to one (different composition). Using the SPADE software (Chao & Shen, 2009), the number of species from the different phytogeographic provinces (Chaco Húmedo, Espinal, Valle de Inundación del Río Paraná, Pampeana) and the number of shared species were calculated.

In addition, the composition of the oligoquetofauna of different phytogeographic provinces was compared by means of a similarity percentage analysis (SIMPER), taking into account the dissimilarity of Bray-Curtis, calculated by means of the PAST ver2.16 program (Hammer, Harper, & Ryan, 2012).

Results

Taxonomic richness: A total of 15 species belonging to ten genera and five families were found during field samplings (Table 1). Lumbricidae was the best represented family with 40 % of all species registered, followed by families Megascolecidae and Ocnerodrilidae both with 20 %, Acanthodrilidae with 13 %, and finally the family Glossoscolecidae with 7 %.

Table 1: Earthworm species found in the province Santa Fe during 2012-2015

| Family/species | Native/ Exotic | Ecological category | Site/s where it was found a | Type of environment | Number provincial districts found |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCNERODRILIDAE | |||||

| Eukerria rosae (Beddard, 1895) | Native | Endogeic | 17 | R | 1: C |

| Eukerria saltensis (Beddard, 1895) | Native | Endogeic | 5, 6 | A/L, L | 2: SC, SJ |

| Eukerria stagnalis (Kinberg, 1867) | Native | Endogeic | 1, 2, 3, 6, 11, 13, 14, 17, 18, 21 | L, H, A, A/L, R, FN | 7: GO, G, SJ, LCa, V, C, LC |

| ACANTHODRILIDAE | |||||

| Dichogaster bolaui (Michaelsen, 1891) | Exotic | Endogeic | 1, 2, 4, 7, 19 | L, H, A/L, HG, FN | 4: GO, V, LCa, SJa |

| Microscolex dubius (Fletcher, 1887) | Native | Epiendogeic | 6, 7, 9, 11, 15, 18, 21, 23 | H, L, HG, A/L, A | 6: SJ, SJa, G, LC, LCa, GL |

| GLOSSOSCOLECIDAE | |||||

| Glossodrilus parecis (Righi& Ayres, 1975) | Native | Endogeic | 23 | A | 1: GL |

| MEGASCOLECIDAE | |||||

| Amynthas gracilis (Kinberg, 1867) | Exotic | Epiendogeic | 19 | FN | 1: LCa |

| Amynthas morrisi (Beddard, 1892) | Exotic | Epiendogeic | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 18, 19 | H, A, HG, A/L, FN | 7: GO, V, SC, SJ, SJa, G, LCa |

| Metaphire californica (Kinberg, 1867) | Exotic | Epiendogeic | 2, 4, 6, 7, 11, 18, 19, 21 | H, A/L, L, HG, FN | 7: GO, V, SJ, SJa, G, LC, LCa |

| LUMBRICIDAE | |||||

| Aporrectodea caliginosa (Savigny, 1826) | Exotic | Endogeic | 2 | H | 1: GO |

| Aporrectodea rosea (Savigny, 1826) | Exotic | Endogeic | 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 13, 15, 18, 20, 21, 23 | L, H, A/L, A | 7: GO, V, SJ, G, LC, LCa, GL |

| Aporrectodea trapezoides (Dugès, 1828) | Exotic | Endogeic | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 18, 19, 21, 22, 23 | A, A/L, FN, H, R | 11: GO, V, SC, SJ, SJa, G, C, LC, LCa, R, GL |

| Bimastos parvus (Eisen, 1874) | Exotic | Epigeic | 18 | H | 1: LCa |

| Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826) | Exotic | Epigeic | 2, 11 | H, L | 2: GO, G |

| Octolasion tyrtaeum (Savigny, 1826) | Exotic | Endogeic | 5, 19, 21, 22, 23 | A, A/L, HG | 5: SC, LC, LCa, R, GL |

References: a See figure 1 to locate the sites. A= Agricultural, A/L= Agricultural/Livestock, R= Roadside, FN= Forestal Nursery, H= Horticultural, HG= Home garden, L= Livestock. Provincial districts= GO: General Obligado, V: Vera, SC: San Cristóbal, SJ: San Justo, SJa: San Javier, G: Garay, LC: Las Colonias, LCa: La Capital, C: Castellanos, R: Rosario, GL: General López.

Five species are native to South America (M. dubius, G. parecis, E. rosae, E. saltensis and E. stagnalis), and the other species were introduced (exotic) from North America, Africa, Asia and Europe. The species E. rosae was a new record, being included in the updated earthworm species list of Santa Fe.

Earthworm assemblages and territorial distribution: The sampled Espinal area recorded the highest species richness (12 = E. rosae, E. saltensis, E. stagnalis, D. bolaui, M. dubius, A. gracilis, A. morris, M. californica, A. rosea, A. trapezoides, B. parvus, O. tyrtaeum) with respect to Chaco Húmedo (10 = E. saltensis, E. stagnalis, D. bolaui, M. dubiu, A. morris, M. californica, A. caliginosa, A. rosea, A. trapezoides, E. fetida), Valle de Inundación del Río Paraná (8 = E. stagnalis, D. bolaui, M. dubiu, A. morris, M. californica, A. rosea, A. trapezoides, E. fetida) and Pampeana (5 = D. bolaui, G. parecis, A. rosea, A. trapezoides, O. tyrtaeum). The assemblage of earthworms in the Pampeana area showed high values of complementarity with both Chaco Húmedo (75 %) and Valle de Inundación del Río Paraná (70 %). According to the SIMPER analysis, the species that most contributed to the dissimilarity between the communities of the phytogeographic provinces were A. trapezoides and A. morrisi. Of the five native species recorded, four: E. rosae, E. saltensis, E. stagnalis and M. dubius, were present in Chaco Húmedo, Espinal and Valle de Inundación del Río Paraná environments.

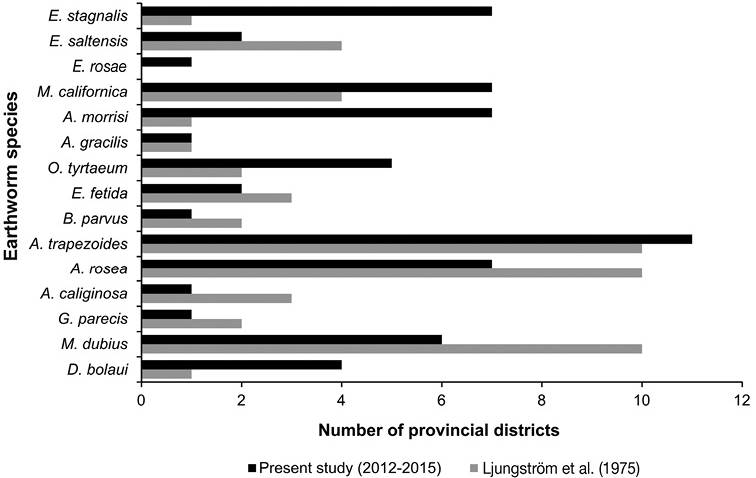

The species A. trapezoides, A. rosea, A. morrisi, M. californica and E. stagnalis were widely distributed, the species A. trapezoides was found in 11 provincial districts and the other species in seven. Conversely, E. fetida was present in two districts and E. rosea, A. gracilis, A. caliginosa, B. parvus and G. parecis were only present in one (Table 1).

Endogeic species were present in all environments surveyed, while epiendogeics in 70 % of the sites (Table 1).On the other hand, exotic epigeic species such as E. fetida and B. parvus, were found only at 13 % of the sites studied, particularly at horticultural sites use (topsoils with organic matter accumulated little decomposed).

Discussion

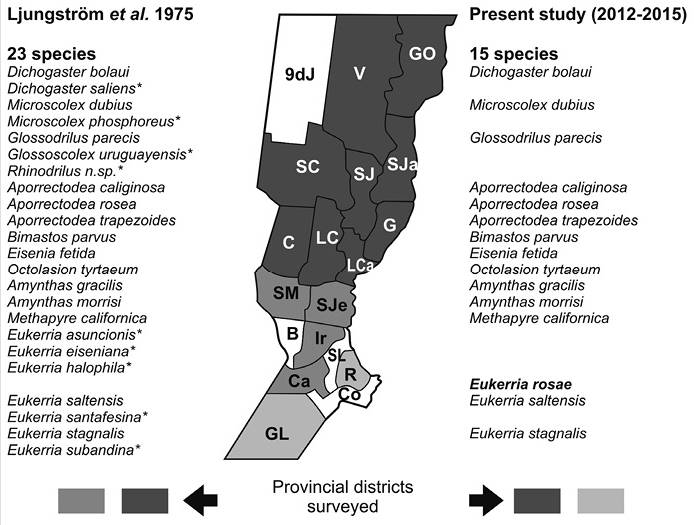

The work of Ljungström et al. (1975) relieved 13 districts, of which 10 were part of the current study (2012-2015). In both, the area studied represented more than 80 % of the total area including a wide latitudinal and longitudinal distribution covered different environments. However, it is important to mention that neither the specific sites of sampling relieved by Ljungström et al. (1975) nor the information about the type of environmental corresponding to districts were reported. Therefore, a strict comparison between both studies is difficult but it is possible to discuss some similarities and difference.

In both works the same families were recorded: Acanthodrilidae, Glossoscolecidae, Lumbricidae, Megascolecidae, and Ocnerodrilidae, but the number of species in the current survey was lower (60 % of the 23 species reported in the study of 1975) (Figure 2). An important difference was marked by native species, where the checklist of Ljungström et al. (1975) showed more than 50 % of the total recorded species, against only 33 % reached in the current study. From this percentage the genus Eukerria, particulary E. stagnalis, was the most widespread and this species was generally found in several agroecosystems (Table 1), establishing differences with the study reported 40 years ago (Figure 3). In addition to this, E. rosae was a new record. Information about this species, and particularly its ecology, is scarce in Argentina. In the current survey E. rosea was found in a soil water-saturated of the roadside. The few studies made in Santa Fe, reported that water-saturated biotopes with organic matter from the local vegetation, are usually inhabited by species of the genus Eukerria (Emiliani, Ljungström, Priano, Gutierrez, & Calamunte, 1971; Emiliani, de Orellana & Ljungström, 1973). Also, studies by Feijoo, Quintero, Fragoso & Moreno (2004) and Grosso & Brown (2007) state that found species of this genus in muddy soils or with high moisture content and associated with plant roots.

Figure 2 Earthworm species recorded by Ljungström et al. (1975) and the current survey (2012-2015). References: (*) not found in current sampling, and bold letter new record. Provincial districts in color indicate sampled. Provincial districts = GO: General Obligado, V: Vera, 9dJ: 9 de Julio, SC: San Cristóbal, SJ: San Justo, SJa: San Javier, G: Garay, LCa: La Capital, LC: Las Colonias, C: Castellanos, SM: San Martín, SJe: San Jerónimo, Ir: Iriondo, B: Belgrano, Ca: Caseros, SL: San Lorenzo, R: Rosario, Co: Constitución, GL: General López.

Figure 3 Earthworm species by provincial districts of province Santa Fe: current survey (2012-2015) and the registry of four decades ago.

The exotic species A. rosea, A. trapezoides, A. morrisi and M. californica were the most widespread. They were present at agricultural sites (crop sites, livestock, mixed crop-livestock farming, horticulture) (Table 1). The genus Aporrectodea, particularly A. trapezoides, has a similar spatial distribution compared to that registered 40 years ago, while the megascoelecids A. morrisi and M. californica significantly increased their area of distribution (Figure 3). These species seem to adapt to the impact of agricultural practices (Feijoo et al., 2004), and may be invasive colonizer / opportunistic, occupying the niche of native species that disappear after environmental transformations such as the replacement of natural vegetation by crop plants (Brown & James, 2007).

In comparison to the situation four decades ago the current study shows a new picture of earthworm species richness and distribution in the province of Santa Fe. This change can be related to the impact of the increase of agricultural activities, which decreased landscape heterogeneity and modified soil properties considerably.

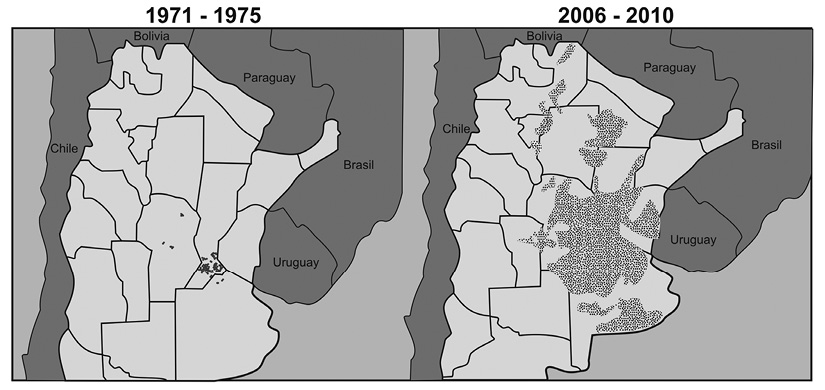

Figure 4 shows the advance of soybean crops during the last 40 years. This situation has produced changes in landscape diversity. Areas of native forest and natural grassland in the Central and Northern parts of the province were replaced by agricultural crops, particularly by soybean (Heredia, Giuffré, Gorleri, & Conti, 2006; Viglizzo et al., 2010; CONICET, 2012). The implementation of continuous agriculture and intensive soil management has resulted in the following consequences: loss of organic matter and nutrients, erosion and thus degradation of soil, resulting in an overall decrease of biodiversity (Miretti, Pilatti, Lavado, & Imoff, 2012).

Figure 4 Advance of agricultural frontier, in particular of soybean crop in Argentina during the last four decades (Modified after CONICET 2012).

When natural grasslands and/or forests are replaced by agroecosystems, changes can occur at the taxonomic (substitution of native species by exotic), ecological (increase or decrease of species number according to ecological categories), or both levels (Fragoso et al., 1999). Consequently, earthworms associated with natural environments, in particular native species, tend to move to other habitats less anthropogenically disturbed (Ramírez Pisco, Guzmán Álvarez, & Leiva Rojas, 2013). This could be related to the results obtained in this work, where species found previously (Ljungström et al., 1975) in natural areas or with low anthropic intervention were not found anymore, for example the native species M. phosphoreus, G. uruguayensis and some species of the genus Eukerria (Figure 2). Other native species, such as G. parecis and M. dubius, were found in ecosystems with lower levels of anthropogenic disturbance. Finally, species of the Eukerria genus, particularly E. stagnalis, were present both in natural environments and agroecosystems with intensive land use (Fragoso et al., 1999).

In agreement with Paoletti (1999); Dupont et al. (2012); Cunha et al. (2016) and Ortiz-Garmino, Pérez-Rodríguez, & Ortiz-Ceballos (2016), the distribution of species is strongly influenced by landscape transformation history, in particular the intensity of changes of soil use (Briones, Ostle, McNamara, & Poskitt, 2009; Tondoh, Guéi, Csuzdi, & Okoth, 2011). In addition, environmental factors such as climate (temperature, but also soil moisture) act as a limitation for the distribution of earthworms.

In this study, 15 earthworm species belonging to ten genera and five families were found in the province of Santa Fe. One species not known from this province beforehand is Eukerria rosae, a native species to South American. Earthworm assemblages of Espinal, Chaco Húmedo and Valle de Inundación del Río Paraná showed greater similarity, while Pampeana (lower richness) showed high values of complementarity with the three phytogeographic provinces. Within the last 40 years, the pattern of earthworm biodiversity changed considerably in this province, a process which is associated with changes in soil use and land management, in particular the increased cultivation of soy.

uBio

uBio