For millennia, roads have allowed the rise of civilizations and the communication of human societies. The global road network is the largest ever, and the current standard of living that humans enjoy would be impossible without it. Humans are not the only species benefited from roads, many other organisms use them for dispersal, and to find resources and mates. Nevertheless, roads also modify habitats and cause wildlife mortality, among several reasons, from collision with vehicles (Trombulak & Frissell, 2000; Brown & Brown, 2013; D’Anunciação, Lucas, Silva, & Bager, 2013; Motley et al., 2016).

It may be thought, as Kroll (2015) did, that the problem of road kills began with the invention of the combustion engine and the “explosion” in the number of roads and automobiles in the early 20th century, but actually the problem has been recorded for thousands of years. Vehicles have been killing domestic animals and wildlife since high-speed chariots were invented more than 4 000 years ago, even though few historians have cared to mention non-human victims of road accidents (Sanborn, 2008; Anthony, 2010; Kroll, 2015). The ancient Roman Stele of Edessa (Fig. 1) represents a pig killed by a vehicle and comments on the accident (Beard, 2015).

Fig. 1 Road kill in the Roman empire: the pig stele of Edessa, Macedonia; the text reads: “A pig, friend to everybody; a four-footed youngster; here I lie... But by the force of a wheel; I have now lost the light... Here now I lie, owing nothing to death anymore”. Photograph by Philipp Pilhofer (Wikimedia.org)

From the point of view of conservation, the negative effects of roads on animal abundance outnumber positive effects by a factor of five, and merit routine mitigation (Fahrig & Rytwinski, 2009). Most scientific work about road kills has been done in temperate ecosystems and the three basic findings can be summarized as follows:

Amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals are the main vertebrate victims of collisions (the situation seems to be worse for large mammals).

Vultures -and some small birds and mammals- are often benefited by roads.

All vertebrate groups have species that seem to be unaffected by roads (either because they do not get close to roads or because they are able to escape from approaching vehicles).

Nevertheless, the problem is at least as serious in the tropics as in temperate regions. For example, extrapolation of data by the Centro Brasileiro de Estudos em Ecologia de Estradas estimated that 430 000 000 small vertebrates (mainly frogs, snakes and birds), 40 000 000 mid-size vertebrates (mainly monkeys, opossums), and 5 000 000 large vertebrates (mainly tapirs, and larger predatory canids and felids) become road kills in Brazilian roads every year (Guimarães, 2015).

Until now, no general review of road kills in the tropics had been published, but some particular groups have been reviewed (D’Anunciação, Lucas, Silva, & Bager, 2013). Even though a couple of recent publications from Latin America did not mention any differences with temperate regions (Figueroa et al., 2014; De la Ossa, De la Ossa, & Medina, 2015), some authors have predicted that differences will be found. For example, collisions with large-sized wildlife are a serious threat to human life in temperate countries but are rare in the tropics (Freitas, Sousa, & Bueno, 2013); and more species are killed by collisions in the species-rich tropics, making conservation more urgent (Freitas, Sousa, & Bueno, 2013).

In this review, I summarize publications that focus on road kills in tropical countries from Africa, America, Asia and Oceania, and compare them with reports from temperate countries.

Materials and methods

I searched Google Scholar, Web of Knowledge, Scopus, JSTOR, Springer Link, Science Direct, and Wiley Online Library, combining the search terms road kill; wildlife vehicle; collision; road; highway and traffic with the following words, that cover all countries with territory in the neotropics and paleotropics (for countries with parts outside the tropics, I also searched for the tropical states or provinces and excluded results from nontropical parts): Costa Rica, Mexico, Zacatecas, Tamaulipas, Nayarit, Aguas Calientes, San Luis Potosí, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Hidalgo, Colima, Michoacán, Querétaro, Tlaxcala, Morelos, Guerrero, Veracruz, Oaxaca, Tabasco, Chiapas, Quintana Roo, Yucatan, Campeche, Puebla, Belize, Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panamá, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, French Guiana, Suriname, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil (Pará, Amapá, Mato Grosso, Manaus, Rio de Janeiro) Cuba, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Trinidad and Tobago, Puerto Rico, Nepal, Yemen, Oman, Somalia, Kenya, Thailand, India, Tanzania, Uganda, Ethiopia, Liberia, Namibia, Angola, Congo, Botswana, Chad, Nigeria, Malaysia, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Australia, Vietnam, Philippines, and Papua. Search dates: June through November, 2017.

I also included the number of records and main species in all the citizen science projects published in inaturalist.org as well as data and publications from the large citizen science project in Sistema Urubu, Brazil (http://cbee.ufla.br/portal/monografias). For comparison, I analyzed the data from a large temperate ecosystems project, California Roadkill Observation System, wildlifecrossing.net. The raw dataset is freely available online as Digital Appendix.

Results

Formal studies: the search produced nearly 2 000 results, but after discarding those that were not original studies focused on road kills from tropical ecosystems, only 73 studies remained for the analysis of this study. The works were from the American continent, Africa, Asia and Oceania, and here I present them in that geographic order, starting with Mexico.

Mexico: Despite its large economy and road network, Mexico has produced few studies about road kills and the design of “environmentally friendly roads” is in a very early stage (González & Badillo, 2013). In Veracruz and Puebla the most common victims were Peromyscus rodents (González-Gallina, Benítez-Badillo, Rojas-Soto, & HidalgoMihart, 2013). There is also a report of a large mammal, a female Tapirus bairdii, killed in Campeche, a paradoxical indication that the species -once thought extinct in the area- was still there (Contreras-Moreno, Hidalgo-Mihart, Pérez-Solano, & Vázquez-Maldonado, 2013). Generally, Mexican authors have stressed the value of road kills as source of scientific data that can be obtained without additional sacrifice of wild organisms (González-Gallina, Benítez-Badillo, Hidalgo-Mihart, Equihua, & Rojas-Soto, 2015).

Costa Rica: Unlike most studies that limit the concept of road kills to wildlife, an early study in Costa Rica included pets and found that cats and dogs are the most frequent victims. Among wildlife species, the opossum Didelphis marsupialis and the anteater Tamandua mexicana dominate road kill numbers. Mammals suffered more casualties (both in individuals and as species), followed by birds and reptiles; amphibians were rarely recorded (Monge-Nájera, 1996). Almost no studies compare casualties with the actual number of animals crossing roads, but this study reports that birds were four times more likely to survive encounters with cars than mammals; it also included invertebrates and found that thousands of pierid butterflies, Eurema sp., become road kills during migration (Monge-Nájera, 1996).

In a secondary road, frogs (Bufonidae) were the main victims (amphibians are generally reported to be rare among road kills, with exceptions, see Vijayakumar, Vasudevan & Ishwar, 2001; Arévalo, Honda, Arce-Arias & Häger, 2017) and that at higher traffic levels, less animals crossed and died, possibly because they were frightened by the heavy traffic (Rojas-Chacón, 2011). Compared to a gravel road, a paved road had more traffic and more deaths, but less individuals and species of mammals approached it. The jaguar, Panthera onca, and the margay, Leopardus wiedii, were seen crossing but did not become road kills; and raccoons, Procyon lotor, frequently used a culvert as underpass (Araya-Gamboa & SalomPérez, 2015).

In a Caribbean road, opossums (D. marsupialis), armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus) and four-eyed opossums (Philander opossum) were the most frequent victims (Artavia et al., 2015). With one exception, the same species led road kill lists in the northern part of the country: D. marsupialis, T. mexicana and D. novemcinctus (Alfaro & Quesada, 2016). An even more recent study is particularly important because it found mass mortality of frogs during the reproductive season (Arévalo et al., 2017).

Colombia: Colombia is among the Latin American leaders in the study of road kills. A decade ago, in Antioquia, marsupials, rodents and predators, including the endangered felids Leopardus tigrinus, Puma yagouaroundi, and the recently discovered procyonid Bassaricyon neblina, were the most common mammal victims. The author of the study recommended education and road signs to mitigate the problem (Delgado-Vélez, 2007; 2014).

More recently, an experiment with marked marsupials (Marmosa robinsoni) and rodents (Melanomys caliginosus, Handleyomys alfaroi, Rhipidomys latimanus and Heteromys australis) found that the animals avoid crossing roads in Yotoco (Vargas-Salinas & LópezAranda, 2012).

In the Magdalena river region, mammals and reptiles were the prevalent victims by both individuals and biomass, while birds followed in number of species and -like in other tropical studies- anurans were rare. The four most frequent victims were T. mexicana, D. marsupialis, crab-eating foxes (Cerdocyon thous) and boas (Boa constrictor). Deaths were not associated with home range, number of safe crossing structures available, or rivers (DiazPulido & Benítez, 2013).

In northern Colombia, more animals died in the dry season, particularly D. marsupialis, the frog Rhinella marina, the vulture Coragyps atratus and the bird Pitangus sulphuratus. A second study in the same area, two years later, reported again R. marina, but found instead other species as the main victims: the snake Leptodeira septentrionalis) and the opossum D. marsupialis (Nadjar & De la Ossa, 2013; La Ossa-Nadjar & De La Ossa, 2015). This difference reflects the complexity of the situation in the tropics.

In Sucre, Colombian Caribbean, the most frequent victims were mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians in similar proportions, particularly the fox C. thous (10.9 %), iguanas (Iguana iguana) and the bird Crotophaga ani. Traffic and species behavior seemed to be the main causes of mortality (De La Ossa & Galván-Guevara, 2015). In Quindío, a study did not find evidence that biological corridors reduced mortality, a problem that has been found in many temperate and tropical areas (López-Herrera, León-Yusti, Guevara-Molina, & Vargas-Salinas, 2016).

Venezuela: In the road between Caracas and Mantecal, the main victim was the caiman, Caiman crocodilus, followed by D. marsupialis and C. thous, at least during the rainy season (Pinowski, 2005). In Portuguesa, the most frequent victims were the snake Leptodeira annulata, the opossum D. marsupialis, and the crocodyle C. crocodilus. Overall, reptiles, mammals and birds were more common, and historically, heavier traffic meant more road kills (Eloy Seijas, Araujo-Quintero, & Velásquez, 2013).

Andes: Four studies report on the Andean highlands of South America, two from Colombia, one from Ecuador and one from Bolivia. In the Colombian Andes, snake counts were unusually high, particularly Atractus cf melanogaster and Liophis epinephelus (QuinteroÁngel, Osorio-Dominguez, Vargas-Salinas, & Saavedra-Rodríguez, 2012). In Ecuador, the most frequent Andean victims were mammals, birds and reptiles. For most species, road kills were more frequent near cattle farms, and for amphibians, near water (Medrano, 2015). In Bolivia, a detailed study of snake mortality in the highlands found that 18 % of victims belong to endemic species; that males die in higher numbers than females; that terrestrial snakes dominate the counts (over species associated with water, trees and the underground); and that less snakes die during the dry season (Sosa & Schalk, 2016).

Brazil and French Guiana: Brazil produces a large number of articles and has some of the most detailed studies about the relationship between environmental characteristics and number of animals killed. In Carajás, the main victims were snakes, opossums (D. marsupialis) and birds; and -unlike other studies- rain had no effect and victim counts diminished from 2003 to 2006 (Gumier-Costa & Sperber, 2009). In the road between Goiânia and Iporá, most victims were mammals (Tamandua tetradactyla, C. thous and Myrmecophaga tridactyla), with only a small proportion of birds, and even less reptiles. Large and small mammals died in similar numbers, and there were no strong seasonal changes or clear effects of vegetation (Ferreira da Cunha, Alves Moreira, & Sousa Silva, 2010).

For small species, counts from vehicles severely underestimate deaths, so the study of Coehlo et al. (2012) used foot surveys. They found that water and artificial lights become “ecological traps” that cause high anuran mortality. But this mortality concentrates on predictable “hotspots” that vary with the species, i.e. traffic bans during the reproductive season would be effective to greatly reduce anuran mortality (Coehlo et al., 2012).

In southern Brazil, bird casualties concentrated near rice fields and wetlands, with more species and deaths in summer and autumn. A small scale, nearby areas had similar kill rates, independent of habitat, perhaps because animals died when attracted to grain fallen from trucks (da Rosa & Bager, 2012). In the Atlantic mountains, victims are mainly mammals, followed by birds and reptiles. While most dead birds did not show a clear relation with landscape features, the following died in greater numbers near higher herbaceous vegetation: reptiles, owls, large mammals, and arboreal mammals. All species suffered more losses near rivers (Freitas, Sousa, & Bueno, 2013).

One of the most significant papers published anywhere about road kills is a study by Teixeira, Coelho, Esperandio and Kindel (2013), because it addresses a central problem in road kill ecology: mortality is usually underestimated because carcasses are removed by scavengers, or are undetected by researchers for a variety of reasons. Using mathematical modeling, Teixeira et al. (2013) found that the number of specimens seen must by multiplied by a correcting factor according to group, 20 times for birds, 5 times for reptiles, and 2 times for small mammals (Teixeira et al., 2013).

In Mato Grosso do Sul, main victims were the bird Cariama cristata and the fox C. thous. The sections of highway closest to cities had more deaths, particularly near dense vegetation (Carvalho, Bordignon, & Shapiro, 2014). In Minas Gerais, most victims were mammals, birds and reptiles, and unexpectedly, no more animals died on paved than on unpaved roads (Machado, Fontes, Moura, Mendes, & Romao, 2015).

In Chapada dos Veadeiros the most frequent victims were Schneider’s toad (Rhinella schneideri), the grassland sparrow (Ammodramus humeralis), and the yellow-toothed cavy (Galea flavidens). There were more deaths in the wet season. More amphibians died near forests, while reptiles and birds died mostly near open vegetation. Mammals died more on unpaved roads (Braz & França, 2016).

In the Amazon-Cerrado transition, reptiles, amphibians and birds were infrequent victims, while mammals were common. In humanimpacted habitat, a frequent victim was C. thous and the armadillo Euphractus sexcinctus, whereas the anteater M. tridactyla and C. thous led the list in protected land (Brum, SantosFilho, Canale, & Ignácio, 2017).

There is a single report from French Guiana, where T. tetradactyla is the most common road kill victim (Catzeflis & Thoisy, 2012).

Brazil has also contributed an important number of articles on methods and other practical problems of road kill ecology. As expected, hot spots (i.e. sections of roads where most killing occurs) depend on the species (Teixeira, Coelho, Esperandio, Oliveira, & Porto, 2013), but their existence also facilitates mitigation, because work on those road sections has a large positive impact, particularly if done with the participation of local communities (Dougherty, 2015). Brazilian scientists have also answered key questions, like how often and for how long do we need to count kills; what correction factors must be used when counting small animals; how much money can be saved with mitigation; and how to make decisions about mitigation more objective.

To obtain a reliable and detailed image of road kill deaths, sampling weekly for at least two years is a good rule, at least for the neotropical species studied in Brazil (Bager & Rosa, 2011; Costa Ascencão, & Bager, 2015; Santos et al. 2017).

Most vertebrate victims are small, with a body mass under 500 g, and in many cases under 100 g, which greatly reduces their chance of being detected because they are rapidly removed by scavengers and because they can only be detected by walking observers (Santos, Rosa, & Bager, 2012; Santos et al., 2016).

Besides the death of wild animals, and even when humans are not hurt, vehicle repair has a cost than may be higher than the cost of mitigation. For example, for capybaras (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), in road sections where more than five animals are killed each year, car repair costs are higher than the cost of installing fences and culverts (Huijser, Abra, & Duffield, 2013).

Mitigation measures are often recommended by researchers without real data about their effectiveness (D’Anunciação et al., 2013), and the few results from the tropics leave little space for optimism (Bager & Fontoura, 2013; Ciocheti, Assis, Ribeiro, & Ribeiro, 2017). A reasonalbe approach is to concentrate mitigation on endangered species and road segments with high mortality as proposed by Bager and Rosa (2010).

Finally, a particularly interesting result from Brazil is the study by Secco, Ratton, Castro, Lucas and Bager (2014) who found that some drivers intentionally run over snakes, but unlike drivers in Australia, Canada or the USA, Brazilian drivers run over control objects with equal speed and frequency. They also found that the behavior is worst among truck drivers, who are less afraid of damage to their vehicles (Secco, et al., 2014).

Africa: African studies have been made in Madagascar, and more recently in Tanzania, Uganda and Ethiopia. A study in Madagascar is of particular interest because it found that construction of two speed bumps significantly reduced deaths for all vertebrate groups along the entire road, suggesting that speed bumps also act as psychological deterrent (Schutt, 2008).

A study in Tanzania found that birds were the most frequent victims, followed by mammals and reptiles (like almost everywhere else, amphibians were rare; but this might be an artifact, see Arévalo, et al., 2017). Mortality was higher near nature reserves, and -excluding birds- nocturnal species suffered more (Kioko, Kiffner, Jenkins, & Collinson, 2015). Just like in Mexico (González-Gallina, et al. 2015), a report from Uganda highlighted that road victims can be used to assess the health status of wildlife without directly affecting their populations, and recommended speed-bumps to reduce risks to wildlife and human pedestrians (McLennan & Asiimwe, 2016).

Mammals and birds had the highest species richness among victims in Ethiopia, where most accidents happened during the early morning and late evening, possibly from a combination of reduced visibility and higher animal and vehicle traffic (Kiros et al., 2016).

Asia: By number of articles, the study of road kills in tropical countries of Asia follows the Neotropics and comes mainly from India, Sri Lanka and Malaysia.

A study of reptiles and mammals in India found more dead reptiles at night and during the rainy season, leading to the recommendation of reducing tourism pressure in critical periods and areas, particularly because some of the victims were members of endangered species (Kumara, Sharma, Kumar, & Singh, 2000). In the Anamalai Hills, amphibians and uropeltid snakes were the main victims, with more deaths during rainy periods; road kills threatened their conservation because of the scarcity of herpetofauna in rainforests (Vijayakumar, Vasudevan, & Ishwar, 2001).

More recent work from India has been done in nature reserves and Bhavnagar city. Reptiles were the most affected in Bandipur, followed by amphibians and mammals, especially during the pre-monsoon (Selvan, Sridharan, & John, 2012). The monsoon seems to increase the mortality of snakes in hotspots that occur mainly in the highlands, far from agriculture fields, animals crossings and water sources (Pragatheesh & Rajvanshi, 2013). In the Durrah and Ramgarh, snakes and lizards were the main reptilian victims, and even though the number was small (a mean of two per month) the cumulative effect was significant for rare species (Nagar, Meena, & Dube, 2013). A similar result was found in Mudumalai: reptiles were the most affected vertebrates, followed by mammals (Samson et al., 2016).

A study in Bhavnagar found a similar pattern of reptiles and mammals dominating the list, while amphibians were rare. Just like in nature reserves, threatened and vulnerable species appeared among the victims, e.g. the striped hyena (Hyaena hyaena); red sand boa (Eryx johnii) and Indian softshell turtle (Nilssonia gangetica), with more deaths when rains were intermittent and animals had to travel in search of water (Solanki, Beleem, Kanejiya, & Gohil, 2017).

Closer to the equator, in Sri Lanka, herpetofauna were also reported as the main victims in nature reserves, particularly during the night and in the high tourist season, making a restriction of speed and visitation the key mitigation measures (Karunarathna, Ranwala, Surasinghe, & Madawala, 2017).

Oceania: Most roads and highways in Oceania remain unstudied. In the case of Australia, work concentrates in temperate parts. In tropical Australia, the most frequently killed native species are the northern brown bandicoot (Isoodon macrourus), the mountain brushtail possum (Trichosurus cunninghami) and the Australian magpie (Cracticus tibicen) (Taylor & Goldingay, 2004). A study in the Palmerston Highway found no evidence that overpasses were useful to reduce losses of the Ringtail Possum, Pseudochirulus herbertensis (Goosem, Wilson, Weston, & Cohen, 2008).

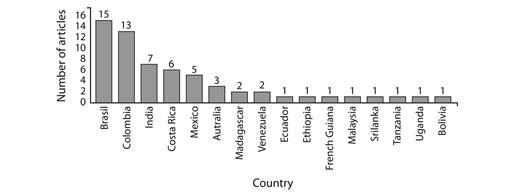

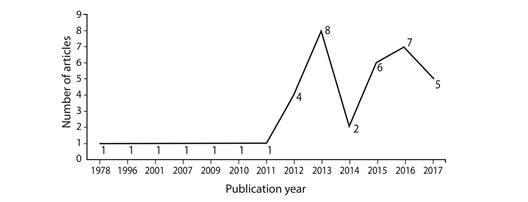

General trends: The number of articles about tropical road kills increased after 2011 but is still small (Fig. 2). The most productive countries by total articles are Colombia, Brazil, Costa Rica, India and Mexico (Fig. 3), but correcting for population size, the leaders are Costa Rica (1.25 articles per million inhabitants), Colombia (0.27 articles per million inhabitants) and Brazil (0.05 articles per million inhabitants).

Fig. 2 Historical trend in the production of scientific articles about road kills in tropical ecosystems.

Once corrected, birds dominate, and are followed by amphibians, reptiles and mammals (Fig. 4 and Digital Appendix 1). These results are based on studies done from automobiles, they do not include the more reliable results about anurans based on foot counts (Teixeira et al., 2013; Arévalo et al., 2017), which fall well within the corrected values.

Fig. 4 Vertebrate groups by total cumulative number of victims reported in the literature about road kills in tropical ecosystems (dark blue). The lighter part of the bars correspond to the estimated real number of deaths, corrected according to Teixeira et al. (2013), by multiplying by 20 times for birds, 5 times for reptiles, and approximately 2 times for small mammals (Teixeira et al., 2013: equation 4 in page 318 and Table 2 in page 321; they do not provide a correction factor for amphibians, but I applied the reptilian value considering that amphibians have a similar size).

Citizen science: Besides scientists, some non professionals have developed an interest in road kills, from dolls inspired in them and sold by a London company named Road Kill Toys (roadkilltoys.com) to their use in food and art (Peterson, 1987; Parry, 2007), and this interest could be harnessed for research and mitigation, but work along this line has hardly started. The development of smartphone applications that allow distance insertion of images and data to servers, led to the establishment of road kill databases that can be used to identify sites and species in need of protection. These “citizen science” databases normally include time, date, location and photograph of the road kill, and a network members who can help in the identification of the species.

A dozen road kill databases were available in iNaturalist at the time of the search, and the second largest is tropical: Fauna Silvestre en Carreteras de Costa Rica, with 939 reports, mainly tamanduas, opossums and raccoons. The other large databases were the Adventure Scientists Wildlife Connectivity Survey (USA) with 9 030 records led by raccoons, opossums and gopher snakes; and the Vashon-Maury Road Kill (Washington State, USA) with 771 records led by the Rough-skinned Newt, Golden-crowned Kinglet and Song Sparrow.

For comparison, data from the scientific literature and the largest temperate and tropical citizen science projects appear in Table 1. The proportions from citizen science projects are different between tropical and temperate sites, and these in turn are very different from scientific reports. Around half of the reports from the citizen science tropical database are from mammals, and amphibians are the smallest group. In the temperate citizen science database, most data are from mammals, and other groups represent less than 20 % in total. By contrast, data from the scientific literature are nearly equally divided among all groups, with a slight dominance by amphibians (Table 1).

Table 1 Percentage of road kill victims by vertebrate group, based on large samples

| Vertebrate group | Scientific articles (Digital Appendix 1) | Temperate Database (wildlifecrossing.net) | Tropical Database (cbee.ufla.br) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amphibians | 34 | 2 | 8 |

| Reptiles | 25 | 5 | 19 |

| Birds | 20 | 12 | 20 |

| Mammals | 21 | 81 | 53 |

Proportions calculated from 23 791 victims added from reports from the scientific literature (Digital Appendix 1; without correction for detectability); 53 678 from the US citizen science project, and 19 113 from the Brazil citizen science project.

Discussion

Every day, millions of animals become road kill in tropical countries, and even though these countries have less resources for their study, they have made significant contributions in the ethical use of road kills for research, inclusion of species other than wild vertebrates, study of often overlooked phenomena like hour of day and failed versus successful crossing attempts, and the value of speed control in mitigation. Every road kill victim is a small ecosystem in itself, with millions of microorganisms and cells that could be studied for parasitic infections, health status, reproductive periods and a myriad other aspects (GonzálezGallina, Benítez-Badillo, Hidalgo-Mihart, et al., 2015; McLennan & Asiimwe, 2016; Motley et al., 2016). Bacteria and other microorganisms (fungi, viruses) are carried alive in tissue bits to new habitats when tires contact remains on the road (Francisco Hernández, personal communication, 2017), an aspect that has never been studied and that hopefully will open a totally new research field in the future: Road Kill Microbiology.

While researchers in temperate countries normally limit themselves to wildlife, some tropical researchers have taken a more complete approach by including urban organisms, including pets and even humans, which also are road kill victims, as well as insects and other invertebrates (and seeds), which die in even greater numbers, thus enriching our knowledge of the problem (Monge-Nájera, 1996; McLennan & Asiimwe, 2016). Emphasis on the observation that merging data from different times of day hides important trends is also part of the valuable tropical contributions (Kumara et al, 2000; Kioko, Kiffner, Jenkins, & Collinson, 2015; Kiros et al., 2016; Karunarathna, Ranwala, Surasinghe & Madawala, 2017). There are no studies of why birds are common victims in Africa and some parts of South America, but rare elsewhere, but apparently the only quantification of their car avoiding success rate is also tropical (Monge-Nájera, 1996).

Tropical researchers have also raised the alarm on the small effect that safe-crossing structures may have (Goosem et al., 2008; Díaz-Pulido & Benítez, 2013; López-Herrera et al., 2016) and emphasized the greater value of actually reducing speed, a measure with satisfactory results in Madagascar, where speed bumps were tested (Schutt, 2008) and in Tikal, Guatemala, where vehicles are recorded by officers at the beginning and end of the road to guarantee enforcement of speed limits (personal observation, 2012).

No overall generalization can be made about the role of season or habitat in road kills because data are different from one study to another, reflecting the complexity of the phenomenon and possibly also methodological limitations. For example, some authors have reported that habitat along the road has no effect on road kills (e.g. Ferreira de Cunha et al., 2010; da Rosa & Bager, 2012; Freitas, Sousa & Bueno, 2013); while others have found that more animals die if the road is close to water (Arévalo et al. 2017), open vegetation (e.g. Medrano Viscaino, 2015) or, depending on the species, forest (Monge-Nájera, 1996; Braz & Franca, 2016; Brum et al., 2017). In similar terms, higher mortalities have been recorded in rainy periods (Viiayakumar et al., 2001) and dry periods (Nadjar & De la Ossa, 2013), while others have found no association (Gumier-Costa & Sperber, 2009). For such a complex phenomenon, data should rarely be merged: the patterns appear to be quite specific for age, sex, species, time of day, season and place (Knutson, 1986; Monge-Nájera, 1996; Machado, Fontes, Moura, et al., 2015; Braz & Franca, 2016).

Additionally, countries with reasonable scientific resources and large road infrastructure in tropical areas, like Australia, Mexico and India (Goosem, Wilson, Weston et al., 2008; González-Gallina, Benítez-Badillo, HidalgoMihart, et al., 2015; Karunarathna, Ranwala, Surasinghe et al., 2017), should have a larger output of articles about road kill and its mitigation: they have much work ahead.

The finding of only 73 tropical studies may be considered small, but it is not far from the 79 found by Fahrig and Rytwinski (2009) for their review of all articles about traffic and animal abundance worldwide. The formal study of road kills began a century ago but is still in its infancy, and despite the larger number of studies done in temperate regions, our knowledge of the problem is poor because of methodological problems, both in temperate and tropical ecosystems. The first problem is that we cannot answer with precision questions such as which organisms are killed, where or when. Indeed we have estimates, but not the actual numbers, and the reason is that many road kills are not visible to researchers because scavengers rapidly remove them, because the corpses end outside the road, because they cannot be identified, or because they are too small to be noticed (Monge-Nájera, 1996; Antworth, Pike, & Stevens, 2005). Unfortunately, as I corroborated during the preparation of this review, some authors fail to follow the advice of Antworth et al. (2005) about limiting conclusions according to the weaknesses of data.

The second problem relates to mitigation: even if the real number of victims were known, we would still ignore if they represented a significant proportion of the population, because the real size of animal populations is mostly unknown and is always changing. In any case, small mitigation measures like underpasses and buffer zones appear to be of little help, and with few mortality studies “before” and “after” the installation of wildlife-crossing structures, their efficiency is hard to evaluate (Spellerberg, 1998; Trombulak & Frissell, 2000; Glista, DeVault, & DeWoody, 2009).

However, before-and-after comparisons can also be unreliable, because changes may be caused by factors unrelated to road kills (Goosem, M., Wilson, R., Weston, et al., 2008; González-Gallina, A., Benítez-Badillo, G., Hidalgo-Mihart, et al. 2015). For example, a decrease in the number of victims after the installation of crossing structures can indeed indicate that the structures are successful; but other causes are possible: the animals may simply have learned to avoid vehicles; may have moved elsewhere; or may be falling in numbers for a myriad other reasons like parasites and food shortages (Ranta, Lundberg, & Kaitala, 2006).

To obtain better road kill data, Trombulak and Frissell (2000) urged experimental research to complement post-hoc correlative studies, but there are ethical difficulties in any experimentation with real animals, and studies with fake victims have limited application (Ashley, Kosloski, & Petrie, 2007); to my knowledge, no one has used fake animals to study the reactions of wildlife but it is reasonable to think that vultures and other visually oriented scavengers and predators could react just like humans do. Better results need double blind experiments, together with treatment and control groups, as done in medical research (see Schulz, Chalmers, Hayes, & Altman, 1995), but apparently, such studies have not been attempted in road kill ecology.

Until new methods allow better answers, we should assume that animals need protection (Fahrig & Rytwinski, 2009). Road-free areas are an extreme but expensive solution (Goosem, 2007; Fahrig & Rytwinski, 2009) and Knutson (1986) remarked that, since road kills affect animal populations, natural selection must be operating on them and leading to adaptation, which seems to be the case as suggested by ethological and morphological adaptations (Laurian et al., 2008; Rojas-Chacón, 2011; Vargas-Salinas & López-Aranda, 2012; Brown & Brown, 2013).

Like the previous temperate-tropical comparison done by D’Anunciação et al. (2013), who compared both results and methods, I did not find any remarkable differences in road kill between tropical and temperate habitats, but earlier suggestions that tropical species are more vulnerable and that collisions with large mammals are less frequent (Laurance, Goosem, & Laurance 2009; Freitas, Sousa, & Bueno, 2013) might be true; we need data to test such hypotheses. Additionally, the little effect of road kill on bird populations found by Bager and Rosa (2012) caused by the relative scarcity of any particular tropical species, deserves special attention by future workers.

The finding that citizen science projects present vertebrate group distributions that are very different from those of the scientific literature is worrisome: I strongly recommend comparative studies to check if this means that citizen science data are too biased to be useful for anything but the identification of hotspots and conspicuous victims.

To make a significant contribution to science and put tropical researchers ahead of merely observational research done elsewhere, I recommendations long term monitoring plans, and experimentation: monitoring to determine what portion of the population is lost to roads, and double blind experiments, with proper treatments and controls, to identify correctly the causes of road kill patterns. The key condition? A stringent respect for ethical guidelines: after all, other animals suffer as much as we do in road accidents.

uBio

uBio