Habitat variation, predator-prey relationships, interspecific and intraspecific competition for resources and reproduction are all strong pressures that drive individual behavior and organism’s distribution patterns (Swigart & Lawrence, 2008). However, many marine invertebrates develop a mode of symbiont life, performing a range of hosts with complex relationships due an environmental adaptation (Baeza & Thiel, 2003, 2007). Some of the most representative and common symbionts found in shallow marine waters are crustaceans, that tend to associate with other organisms where they can find shelter, food supply and a safe place to reproduce (e.g.Wirtz, Melo & Grave, 2009).

Sand dollars are naturally found in sandy substrates, on the surface or buried just below the surface (Hyman, 1955). Seasonal and interannual variations in the spatial distribution are due to active migration (Beddingfield & McClintock, 1993) or passive displacements caused by seasonal weather changes (Borzone, 1992, 1993).

The sand dollar Encope emarginata (Leske, 1778) occurs from Argentina to the Caribbean Sea, despite the OBIS database (http://iobis. org/) show their distribution to the north of the United States, being found in shallow unconsolidated substrate generally euhaline estuarine regions or on the continental shelf to a depth of approximately 20 meters (Gray, Downey & Cerame-Vivas, 1968). The large-scale distribution of sand dollar could be affected by depth, hydrodynamics and substrata (Merrill & Hobson, 1970) but the small-scale distribution can be controlled by particle size and food availability (Swigart & Lawrence, 2008).

Associated with this irregular echinoid living a tiny crabs Dissodactylus crinitichelis Moreira, 1901 within a dense coat of spines on the oral side of several species of sand dollars (Gray, Downey & Cerame-Vivas, 1968; George & Boone, 2003). According with Werding and Sanchez (1989) this species has a large distribution ranging from North Carolina (USA) as far to the south as Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil) which apparently is not the same distribution of their hosts, but Martins and D’Incao (1996) consider the distribution to the Argentine.

Dissodactylus crinitichelis has been reported previously to be associated not only with Encope emarginata as well as the species of irregular urchins like Encope michelini L. Agassiz, 1841 (Williams, Mccloskey & Gray, 1968), Clypeaster subdepressus (Gray, 1825) (Schmitt, Mccain & Davidson, 1973) and Leodia sexiesperforata (Leske,1778) (Telford, 1982) and Meoma ventricosa (Lamarck, 1816) (Wirtz, Melo & Grave, 2009).

Many authors consider the genre Dissodactylus as an early stage of evolution of parasitism, especially because it not display clearly any kind of body modifications for this habit (Telford, 1978). It means that D. crinitichelis can feed directly into the food supply of its host. Nevertheless, Telford (1982) shows a high degree of parasitism, where 50 % to 100 % of food sources comes from the body parts of their hosts. The symbiotic status of many species of Pinnotheridae crabs are controversial and it is not clear if they feeding exclusively upon fluids and tissue of their host (Campos, de Campos & de León-González, 2009). Thus, sand dollar provides not only protection but also food to the crab.

Generally, Dissodactylus species present a high degree of variation in abundance in their hosts. This pattern suggest that migration and emigration between hosts could regulate infestation. However, it is unclear whether the presence of crabs can affect the fitness of hosts and if this effect may be dependent on the abundance of crabs that a sand dollar is capable of hosting. If we consider that sand dollar act as substrate for symbionts then, they are subject to the process of intraspecific competition for space.

Based on this assumption, the aim of this work was describe the spatial distribution of the irregular echinoid Encope emarginata in a tidal flat and relate the abundance of ectosymbiont Dissodactylus crinitichelis to their body size. We hypothesize that the abundance of crabs will be positively correlated with sand dollar size. In addition, we measured the rate of movement of echinoids to complement the dynamics of motion and spatial distribution.

Materials and methods

Study site

The Paranaguá estuarine complex (PEC) is a large subtropical system formed by three different smallest estuaries with strong environmental gradients of salinity and energy (described by Lana (1986) and Netto and Lana (1997)). The climate in this region is classified as Cfa according to Köppen-Geiger (i.e. rainy temperate [C], raining all year around [f] and average temperature of the warmest month above 22 °C [a]) (Vanhoni & Mendonça, 2008; Alvares, Stape, Sentelhas, Gonçalves & Sparovek, 2014).

Local tides, with syzygy amplitudes around 2 m, are characterized by diurnal inequalities and semi-diurnal patterns during spring tides. In the east-west axis, the PEC is divided into three sectors as salinity, mesohaline (5 - 15), polyhaline (15 - 25) and the euhaline (> 25) (Netto & Lana, 1996). This system’s dynamics are strongly influenced by tidal currents that override the effect of adjacent river flows. The euhaline sector suffers greater influence of seawater; tidal flats are basically formed by well-sorted fine sand with low organic matter concentration (Marone, Machado, Lopes & Silva, 2005; Noernberg et al., 2006). Cobras island (25° 29’ 5” S - 48° 25’ 48” W) is located on euhaline sector of the estuary where salinity vary between 23 and 33 (Passos et al., 2013). This island is composed by two hills (crystal formation), whose peaks are distant about 500 m, among them there an area of sedimentary nature. The study was conducted in the shallow subtidal region, between 0.5 and 1.5 m deep of Cobras Island.

Field and Lab Routines

To assess the sediment composition (fractions of particle size of sand, carbonates and organic matter) 24 samples were collected in the study area. A particle size analyzer Microtrac S3500 determined the sand fractions. In the laboratory, the carbonate content was calculated as the difference between the initial and final weights of each sample after chemical exposure to a 105 (v / v) solution of hydrochloric acid (HCl) for 24 h (Dean, 1974). Organic matter concentration was also calculated, as the difference between the initial and final weights of each sample after oxidation with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 35 %) for at least 24 h (adapted from Gross, 1971).

Two sampling campaigns were conducted to study the spatial distribution of sand dollars, one in September 2011 (winter) and another in May 2012 (autumn). Before starting the survey of the spatial distribution, during the ebb tide in the morning period, measurements of salinity and water temperature were taken. In each sampling campaign, four (Set / 11) and three (May / 12) transects parallel to the beach (30 m distant from each other) were established inside the tidal flat. In each transect, sample areas of 4 m² (2 x 2 m) were established 10m far from each other and all specimens of Encope emarginata observed in the sample areas were counted. In another moment, 164 sand dollars were randomly collected and measured on the longitudinal and transverse axes in the oral view using a millimeter ruler in situ and the amount of symbionts by host was counted.

In May (2012), we measured the rate of locomotion of sand dollars in the field during daylight, where 30 individuals were selected and removed from the sediment. Their axes were measured and posteriorly they were repositioned in front of a mark (wood tongue depressors with a reference number). The distance of the trail in the sand behind the organisms and the mark were measured in three different stages (approx. 20, 45 and 80 min after repositioning). Through the measure of the trail (mm) and the time between beginning and the end of the experiment (min), the rate of locomotion (mm.min-1) was calculated. After all measurements the sand dollar were returned alive and with no damage to the same general location on the sand from where they were collected.

Statistical Analyses

Maps of distribution of organisms (with a kriging approach) were made to understand the spatial dynamics of population. Furthermore, the dispersion pattern of Encope emarginata was estimated using a dispersion index (DI). This index is equivalent to the ratio between variance (S²) and mean number of individuals per sample area and for each transect (Elliott, 1977). In addition, the dispersion index for Dissodactylus crinitichelis per host and months was calculated. Deviations from the random distribution were estimated by exact permutation tests for D (Clarke, Chapman, Somerfield & Needham, 2006). The statistic D shows a result of two-tailed test where, 0.025 for significant overdispersion and 0.975 for significant underdispersion. Analysis of covariance ANCOVA were made to test for significant relationships between crab abundances and size of sand dollars (longitudinal and transverse axes measurements) and if these relationships are dependent of season (season were included as an independent covariate in the model). Differences between stages of movement were compared through one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Least squares regressions were used to test for significant linear correlations between the longitudinal axes and rate of movement.

Results

The sediments of subtidal flat were composed of fine sands (2.59 phi, SD = 0.08), ranging from poorly to moderately sorted, with 4.69 % (SD = 1.14) of fine grains. The mean percentage of organic content was 0.80 % (SD = 0.40) and the mean calcium carbonate (CaCO3) content was 1.14 (SD = 0.69). Furthermore, mean photosynthetic pigments contents (chlorophyll-a and phaeopigments) were, respectively, 10.94 µg.g-1 (SD = 8.1) and 15.5 µg.g-1 (SD = 5.77). The salinity was 26 at the campaign of Sep/11 and 28 in May / 12. The temperature varied even less, 18 °C in Sept / 11 and 18.5 in May / 12.

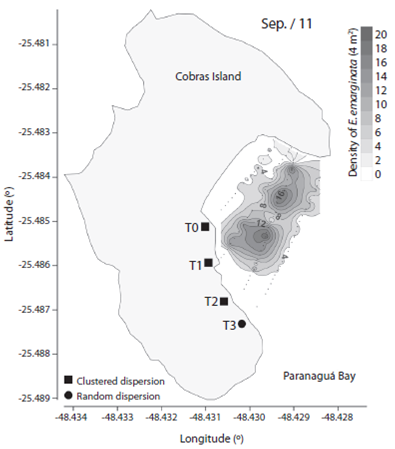

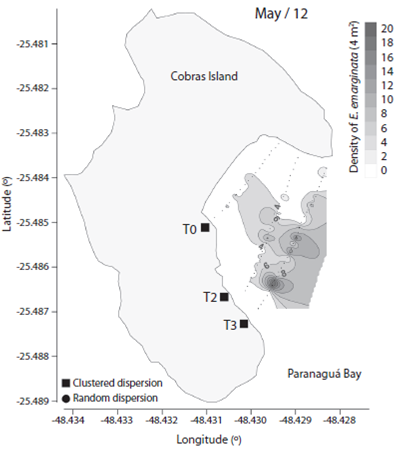

We observed 906 specimens of Encope emarginata (558 in Sep / 11 and 348 in May / 12). This sand dollar had an aggregate distribution pattern with patches of different densities within transects and periods (F2, 15 = 9.466, p < 0.01). Sand dollar patches were observed near to the coast in Sep / 11 (Fig. 1) compared with May / 12 (Fig. 2). The density of E. emarginata range from zero to 20 ind.4 m-².

Fig. 1 Density and dispersion index of Encope emarginata by 4 m² for September (2011) in the tidal flat of Cobras Island in Paranaguá Bay - Brazil (Kriging Approach).

Fig. 2 Density and dispersion index of Encope emarginata by 4 m² for May (2012) in the tidal flat of Cobras Island in Paranaguá Bay - Brazil (Kriging Approach).

The dispersion indices are show in Table 1. Distribution of Encope emarginata displayed a random dispersion pattern in only one of the seven transects off Cobras Island (deepest Sep / 11). In the remainder six transects E. emarginata was clumped distributed. The symbionts Dissodactylus crinitichelis present a more variable distribution pattern if compared with sand dollars. In Sep / 11, crabs were clumped distributed as well as sand dollars. On the other hand, in May / 12 D. crinitichelis was random distributed, displaying a distinct pattern than those observed for E. emarginata hosts.

Table 1 Dispersion index (DI) obtained for Encope emarginata in each transect and for Dissodactylus crinitichelis in all transects together

| Date | Level | Mean Variance DI | n | Dispersion | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | - | Encope emarginata (ind.4m - ²) | - | - | - | ||

| September / 11 | T0 | 2.438 | 7.196 | 2.952 | 16 | Clustered | p > 0.975 |

| - | T1 | 5.714 | 21.514 | 3.765 | 21 | Clustered | p > 0.975 |

| - | T2 | 8.382 | 42.243 | 5.040 | 34 | Clustered | p > 0.975 |

| - | T3 | 4.222 | 5.564 | 1.318 | 27 | Random | p = 0.05 |

| May / 12 | T0 | 2.158 | 4.251 | 1.970 | 19 | Clustered | p > 0.975 |

| - | T2 | 3.750 | 6.194 | 1.652 | 28 | Clustered | p > 0.975 |

| - | T3 | 6.313 | 27.577 | 4.369 | 32 | Clustered | p > 0.975 |

| - | - | Dissodactylus crinitichelis (ind.host -1 ) | - | - | - | ||

| September / 11 | all | 3.863 6.417 1.661 | 102 | Clustered | p > 0.975 | ||

| May / 12 | all | 2.806 3.962 1.412 | 62 | Random | p = 0.05 | ||

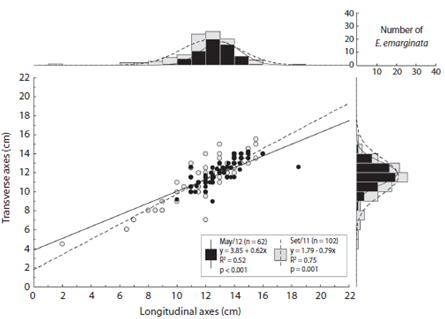

The longitudinal and transverse axes of Encope emarginata (Fig. 3) range respectively from two to 16 cm and 4.5 to 15.5 cm in Sep / 11. In May / 12, they range from ten to 18.5 cm and nine to 14.2 cm. In both campaigns, the most representative class was 12 - 13 cm, with 26 organisms in Sep / 11 and 20 in May / 12. In addition, there is a strong linear relationship between longitudinal and transverse axes (r = 0.837, p < 0.05). No differences between the months sampled were observed (ANCOVA: df = 1, f = 3.5, p = 0.06)

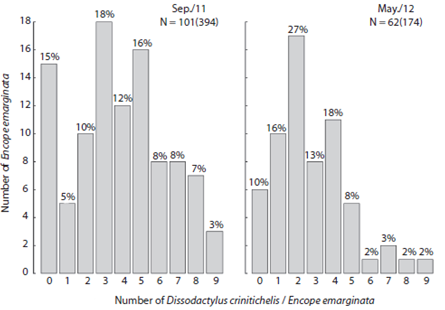

The abundance of Dissodactylus crinitichelis per sand dollar ranged from zero to nine (Fig. 4). Average abundances were higher during Sep / 11 (3.86, SD = 2.53, n = 102) compared with May / 12 (2.8, SD = 1.99, n = 62) (F1, 16 = 7.834, p < 0.05). Three crabs per hosts were more frequently observed in Sep / 11 (18 observations), whereas two crabs per host were more frequent in May / 12 (17 observations). Furthermore, the number of Encope emarginata without symbionts in Sep / 11 was higher (n = 15) than in May / 12 (n = 6).

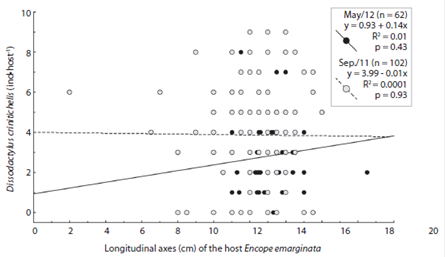

No relationship between size of Encope emarginata and the number symbionts was observed (Fig. 5; Longitudinal axes: r = - 0.021, p < 0.05; Transverse axes: r = -0.017, p > 0.05). Refuting the hypothesis, that space is a limiting resource for the crabs. The ANCOVA test did not detect differences in the ratio (number of guests by the host size) when compared between months (ANCOVA: df = 1, f = 0.39, p = 0.52).

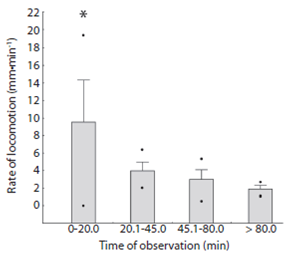

The locomotion rate of Encope emarginata (Fig. 6) ranged from zero to 19.33 mm.min-1 and was higher in the first observation time compared to the others (F3, 36 = 12.535, p < 0.05). In the first observations time (20 min) rate of locomotion ranged from zero to 19.33 mm.min-1. In the second observation time (between 20 - 45 min), the rate varied from two to 7.5 mm.min-1, at the third time (between 45 - 80 min), the rate decrease to a range of 0.5 to 5.32 mm.min-1. Finally, at the last moment (above 80 min of observation) sand dollars crawled in a rate that varied from 0.99 to 2.69 mm.min-1. Considering only the three last intervals (> 20 min), the average rate locomotion of Encope emarginata was 3.08 mm.min-1 (SD = 1.56). The sea biscuits observed in the experiment had a slow and unidirectional locomotion behavior, rather than fast and contrariwise movements. Also, there wasn’t a significant correlation (F1, 37 = 0.0009, R² = - 0.027, p = 0.9758) between size (longitudinal and transverse axes) and their average rate of locomotion. Even when tested using an ANCOVA (df = 3, f = 1.392, p = 0.264), where the size of sea biscuit was using as covariate between the rate of locomotion and time categories.

Fig. 3 Longitudinal axes (cm) versus Transverse axes (cm) of Encope emarginata individuals at Cobras Island - Paranaguá estuarine complex (PEC). On the axes of the scatterplot are histograms showing the number of organisms in each measured variable. Gray dots and bars show the data from September (2011) and the black from May (2012).

Fig. 4 Frequency distribution of Dissodactylus crinitichelis (ind.host-1) by Encope emarginata individuals at Cobras Island - Paranaguá estuarine complex (PEC) during September (2011) and May (2012).

Fig. 5 Longitudinal axes (cm) of Encope emarginata versus number of Dissodactylus crinitichelis (ind.host-1) at Cobras Island - Paranaguá estuarine complex (PEC). Gray dots show the data from September (2011) and the black from May (2012).

Discussion

No relationship between the number of crabs and size of sand dollars was found, refuting the hypothesis that intraspecific competition for space could drive distribution patterns of ectosymbiont crabs on their host. Recently, Martinelli-Filho, dos Santos and Ribeiro (2014) found a similar result, about 360 km north (Lat. 23° 4’ S). However, the authors consider the relationship between host size and number of hosts as positive even though their results showed a low coefficient of determination and consequently a low model fit. Interestingly, these authors also found the same maximum number of guests per host (n = 9), could this be the maximum number of hosts that support sea biscuits?

In our study, we observed that the distribution patterns of Dissodactylus crinitichelis were influenced by the distribution of their host population, rather than by one single host specimen. In Set / 11 when sand dollar population was located near to shoreline, D. crinitichelis was clumped distributed. Whereas in May / 12 when host population was located relatively distant to shoreline compared with Set / 11, D. crinitichelis was random distributed. The aggregated pattern of distribution is one of the general laws of parasitology (as shown Poulin, 2007), possibly this random distribution is not normal. However, George and Boone (2003) found the three possible forms of distribution and related them to the population age distribution. Therefore, it is extremely necessary to understand the real relationship between the host and guest.

Host distribution influences the aggregate pattern of crab population (Baeza & Thiel, 2007), however, distribution of symbionts may be associated with reproductive traits and mating behavior. A recent study suggest that D. crinitichelis may be territorial (Peiró, Baeza & Mantelatto, 2013). The presence of adult females in the host can lead to a single male occurrence due to intraspecific competition, as can be seen when the numbers of hosts with one and two guests are compared between sampling campaigns (Fig. 4). Although evidences that a congener specie D. primitivus have a polygamous mating system where males and females move between hosts for mate search (Peiró, Pezzuto & Mantelatto, 2011; Jossart et al., 2014; Martinelli-Filho, dos Santos & Ribeiro, 2014). Here, we hypothesize that both visions are complementary. In our opinion is possible a polygamous mating system evolve based on interspecific competition. Furthermore, this is an interesting hypothesis, which can be tested experimentally.

When crabs leave their hosts there is a tradeoff between improvements in nutritional, reproductive conditions, and predation risks. In addition, symbionts movements between hosts were strong influenced by the size and abundance of the host (Thiel & Baeza, 2001). Dissodactylus appears to tolerate additional adults of the same species (Gray, Downey & Cerame-Vivas, 1968; Martinelli-Filho, dos Santos & Ribeiro, 2014). This suggests that other factors (e.g., the spatial distribution and connectivity between patches within a population of sand dollars) may be more important for the population dynamics of D. crinitichelis than competition for space per se.

Previous studies suggest that this relationship between host size and number of crabs can be influenced by the ability of echinoids to dig (Dexter, 1977). Larger specimens of sand dollar have greater bulldozing capacity and inhabit deeper sediment layers when compared to smaller size classes, thereby minimizing ectosymbionts infestation (Werding & Sanchez, 1989).

Apparently, Encope emarginata is able to orient and has an escape behavior (see Ebber & Dexter, 1975 and Campbell, Coppard, D’Abreo & Tudor-Thomas, 2001). The rate of locomotion and deviation was higher when compared to the observations made after 20min (Fig. 3). This result may demonstrate the need to burrow and escape in response to the stress caused by manipulation. Discarding the first category of observation (due escape and acclimate behaviors) the average rate of locomotion E. emarginata is 3.081 mm.min-1 (in fine grain sand). This rate is very similar to the measured for D. excentricus that has 3.1 mm.min-1 (Merril & Hobson, 1970). Justifying that the sand dollars are capable to move yourself voluntarily and thus, migrate to the deeper regions to feed, reproduce or to remove parasites.

Merril and Hobson (1970) showed a positive relationship between the size of the sand dollar Dendaster excentricus and its locomotion rate. In our study, this relationship was not observed. These differences can be a response of a small number of size classes comprised in our set of measurements, or this species shows no relationship between the size and ratio of locomotion.

Encope emarginata was clumped distributed in both sampling times. In Sep / 11 the small population was aggregated near to the shore line forming two well defined clusters, although in the last transect (approx. 90 m offshore) sand dollars were random distributed. In May / 12 can be observed which appears to be the same two clusters aggregated in the last transect. This was assumed based on our estimations of sand dollar locomotion rates that not exceed 4.64 mm.mim-1 (excluding de first 20 min of re-adaptation). In addition, the absence of differences on sand dollars’ biometry between sampling periods indicate that in both sampling campaigns the population observed was the same.

Sand dollars are frequently observed aggregated in the sediment and variations in the spatial patterns of distribution may be a function of changes on local hydrodynamic regime (Salsman & Tolbert, 1965; Timko, 1976; Lane, 1977; Bentley & Cockcroft, 1995a, 1995b). During periods of high turbulence and wave energy, sand dollars migrate to deeper areas reducing friction with water column. This dispersion can occur to avoid the disruption of patches that was commonly attributed to storms (by Merrill & Hobson, 1970). Furthermore, variations in the spatial pattern of Mellita quinquiesperforata were observed due climate fluctuations (Bell & Frey, 1969; Borzone, 1992, 1993). Dendraster excentricus, were found aggregated at greater depths during months with high turbulence and wave energy associated to atmospheric cold fronts (Merrill & Hobson, 1970; Morin, Kastendiek, Harrington & Davis, 1985). Whatever the reason, apparently these sea biscuit are able to orient themselves and regroup in patches. Whether as a result from a mutual attraction or attraction to patches of favorable habitat (Bell & Frey, 1969; Birkeland & Chia, 1971).

Both, hosts and their guests may have distribution patterns and migration behavior altered by feeding, reproduction and recruitment processes and possibly with synchronized times. Rhythms in overall activity of echinoids are usually associated with feeding activities (Reese, 1966; Dexter, 1977) or predation (as discussed by Hilber, 2006). When there is no physical limitations, distribution of deposit feeders (like Encope emarginata) may be regular or random and strongly controlled by competition for food (Levinton, 1972; Ebber & Dexter, 1975). It is the reason why Encope emarginata populations were found in sediments composed by fine sands with high organic matter contents inhabited by a rich microphytobenthic biofilm composed for bacteria, microalgae and other micro-eukaryotes. High variation on diatom densities at cm, m and 10m were observed in the study area (Brustolin, Thomas, Mafra Jr. & Lana, 2014). These microorganisms are highly patchy distributed and both top-down and bottom-up controls exert influence on distribution patterns of microphytobenthos and sand dollars.

In our study, we advocate that the distribution pattern of Dissodactylus crinitichelis was influenced by the distribution of host population. Further studies must be conducted to understand the relationships between life cycle and sexual maturation of crab populations and the distribution of its sand dollar hosts. In addition, the degree of association between host and symbionts, that despite being too studied still appears unclear, should be better investigated with aid of computational modeling and genetic tools. Finally, to deeply understand the population dynamics of these little crabs, studies should consider metapopulation concepts and connectivity between patches (as in landscape ecology).

uBio

uBio