Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO  uBio

uBio

Share

Revista de Biología Tropical

On-line version ISSN 0034-7744Print version ISSN 0034-7744

Rev. biol. trop vol.57 suppl.1 San José Nov. 2009

Plants and butterflies of a small urban preserve in the Central Valley of Costa Rica

Kenji Nishida1,3, Ichiro Nakamura2 & Carlos O. Morales1

1. Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, 11501-2060, San José, Costa Rica.

2. 41 Sunrise Blvd., Williamsville, NY 14221, USA; inakamur@buffalo.edu

3. Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, 11501-2060, San José, Costa Rica; kenji.nishida@gmail.com

Abstract: Costa Ricas most populated area, the Central valley, has lost much of its natural habitat, and the little that remains has been altered to varying degrees. Yet few studies have been conducted to assess the need for conservation in this area. We present preliminary inventories of plants, butterflies, and day-flying moths of the Reserva Ecológica Leonelo Oviedo (RELO), a small Premontane Moist Forest preserve within the University of Costa Rica campus, located in the urbanized part of the Valley. Butterflies are one of the best bio-indicators of a habitats health, because they are highly sensitive to environmental changes and are tightly linked to the local flora. A description of the RELOs physical features and its history is also presented with illustrations. Approximately 432 species of ca. 334 genera in 113 families of plants were identified. However, only 57 % of them represent species native to the Premontane Moist Forest of the region; the rest are either exotic or species introduced mostly from lowland. More than 200 species of butterflies in six families, including Hesperiidae, have been recorded. Rev. Biol. Trop. 57 (Suppl. 1): 31-67. Epub 2009 November 30.

Key words: biodiversity, urban biological conservation, day-flying moths, Lepidoptera, premontane moist forest, Costa Rica.

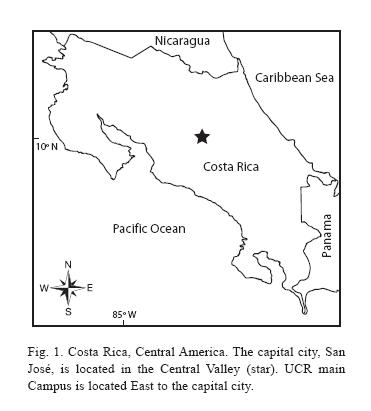

Costa Ricas Central valley (Fig. 1), where the capital city of San José is located and over 40% of the countrys entire population reside (ICT 2007), may be roughly defined as an area delimited by Carrizal, Grecia to Turrúcares in the Northwest, Cerros de Escazú in the Southwest, Cerro de Ochomogo in the Southeast, and El Zurquí de Moravia in the Northeast. Along the edges of the valley are several protected areas, such as the upper part of Cerro Carpintera, Cerros de Escazú, Braulio Carrillo National Park bordering El Zurquí, and Zona Protectora El Rodeo, but these are essentially located outside the Valley. The flat land of the Central valley, the so-called Meseta central, has long been the coffee belt (León 1948). Further reduction of the natural habitats (Sánchez-Azofeifa et al. 2001, Vega & Valerio 2002, Bertsch 2006, Programa Estado de la Nación 2006) and uncontrolled introduction of exotic and other non-local ornamental plants (Chacón & Saborío-R 2006), especially in San José and other populated areas of the Central valley, have adversely affected the biodiversity in these areas. Lack of substantial green space that preserves natural vegetation within these populated areas is another major contributing factor to this trend.

Efforts towards the inventory of Costa Ricas biodiversity of plants, fungi, insects and some other invertebrates were pioneered by the National Museum at the end of the XIX century, by the University of Costa Rica since 1941, the National University (since 1973), and recently by the Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad (INBio). The latter uncovered approximately 2500 new species in the last 17 years of operation (INBio 2004, 2005, 2007), and the massive caterpillar rearing project led by D.H. Janzen & W. Hallwachs over nearly 30 years has produced a large and invaluable database on the Lepidoptera and their parasitoids of the Area de Conservación Guanacaste (Janzen & Hallwachs 2007a, b). These projects specifically target large protected areas. It is unfortunate that much less attention has been given to the unprotected areas and urban preserves, where rapid and extensive destruction, fragmentation and alterations of natural habitats are in progress at an ever accelerating pace. Clearly, an urgent need exists for preserving natural habitats and studying what may still survive in such areas. Nowhere is this need more acute than in the Central valley (see Discussion), yet only a few such studies have been conducted thus far with regard to butterflies. Besides Devries (1987, 1997), which covers the entire country, the list of butterflies found in the Pre-montane Wet- to Tropical Moist transition to Premontane Forest (Holdridge 1967, Bolaños et al. 1999) of Zona Protectora El Rodeo by Vega & Gloor (2001) may be the only relevant survey available, even though it again deals only with large protected areas. Fultons list (1966) of Central valley butterflies is older, but the species obtained outside the Central valley are included without distinguishing them from the former, depriving it of potential usefulness for the current purpose. With regard to plants, the floristic composition study in Zona Protectora El Rodeo done by Cascante M. & Estrada Ch. (2001) is probably relevant; although El Rodeo is strongly influenced by the dry Central Pacific climate.

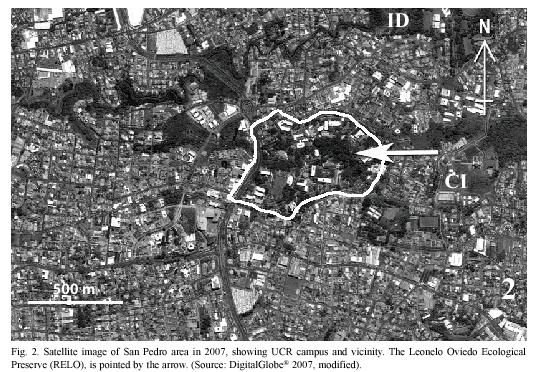

It is in these contexts that we present here the results of our survey of the plants and butterflies in the Reserva Ecológica Leonelo Oviedo (RELO). This small urban preserve is located on the campus of the University of Costa Rica (UCR) in San Pedro, entirely surrounded by an urban environment (Fig. 2). Besides many small student projects related to class assignment and others conducted in the Preserve, only three previous studies on the RELO are known with regard to the butterflies and plants. G. Stiles (unpublished & pers. comm. 2005) mark-recaptured ithomiine butterflies between 1975 and 1981; Di Stéfano et al. (1996) studied regeneration of the forest and included a list of tree species; and A.C. Guardia Orozco (1998) examined the number of species of butterflies to analyze the island effect, namely the relationship between the area size and the number of species in fragmented habitats. Additionally, an unpublished list of the papilionid, pierid, and nymphalid butterflies was compiled in 1996 by P. E. Hanson based on the collection of insects at the School of Biology, UCR.

We present preliminary lists of plants and day-flying macrolepidoptera of the RELO and UCR campus for the first time as part of the foundation for biological and ecological studies in urban ecosystems (Pickett et al. 2001). Physical description and illustrations of the Preserve and its history, and some photos of butterflies and plants are included. Current conditions of the RELO and its conservation need and importance are discussed.

Materials and methods

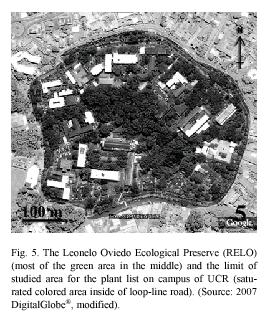

Identification of plants (Pteridophyta, Spermatophyta: Gymnospermae, Angiospermae: Liliopsida, Magnoliopsida) was conducted mostly during August and September, 2007, using live materials and observations through binoculars, in and outside the RELO on campus, but not beyond the Loop line Road (Fig. 5). Most of the plants were reviewed and identified by the third author (C.O.M.); some were collected and pressed for identification at a later time. Nearly all of the recently planted tree saplings were not included in the list, because it is unknown whether these trees will survive.

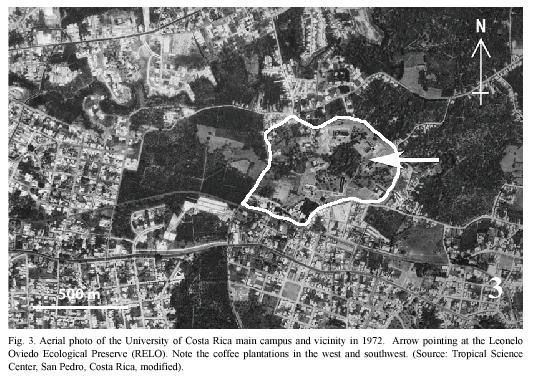

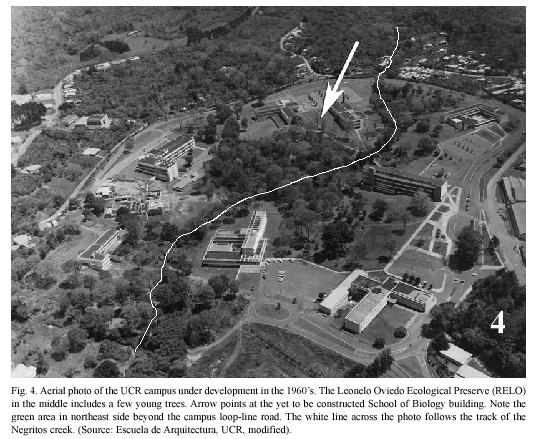

Study site: Reserva Ecológica Leonelo Oviedo (RELO) (ca. 1160 m above sea level; 09°5615N, 84°0300W), commonly known as bosquecito (small woods), is located on the campus of UCR, in San Pedro de Montes de Oca, San José province, Costa Rica (Figs. 1,2,3,4,5). It is located approximately in the center of the loop-line road and contiguous northwestward from the School of Biology building.

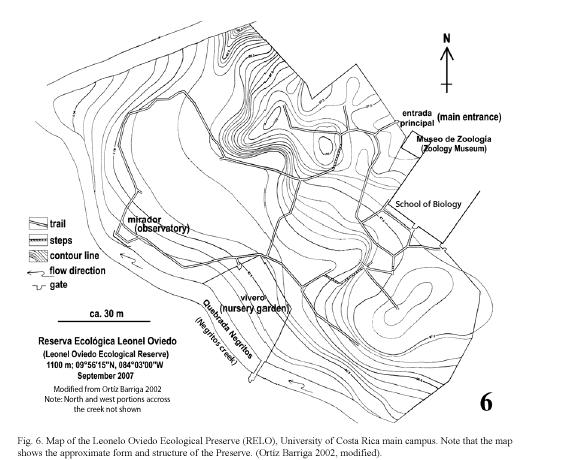

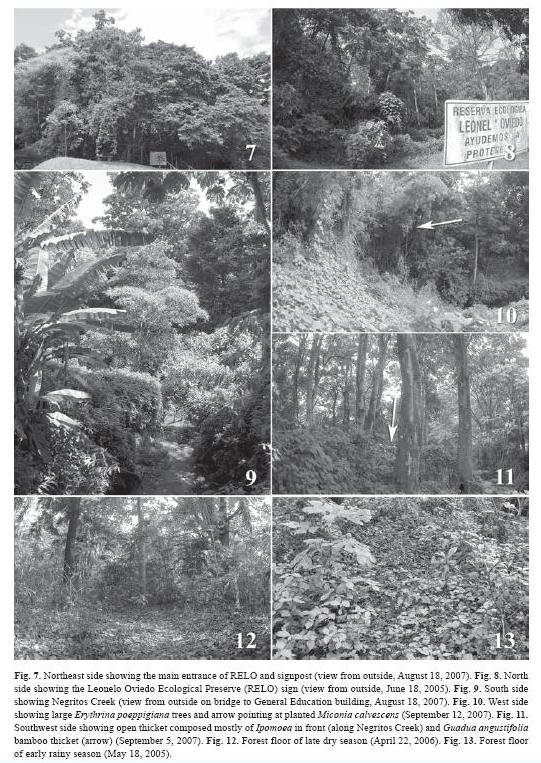

The University campus is located in a large urbanized area of Montes de Oca, one of the 12 metropolitan counties of San José (Bertsch 2006), and the surrounding areas are therefore highly disturbed (Figs. 1, 2). The RELO is a 37-year old secondary growth forest, formerly a coffee plantation (Fig. 4) (J. Di Stéfano, pers. comm. 2007), covering an area of approximately 1.5 ha. (ca. 100 x 150 m) and more or less bordered by the Negritos creek several meters wide, one running through the north and the other on the west side (Fig. 6). The ecological life zone is Premontane Moist Forest after Holdridge (1967) & Bolaños et al. (1999), though this designation is not concurrent with current habitat conditions. The biotic condition is moist subtropical with 5 or 6 dry months annually according to Herrera S. & Gómez P. (1993). The RELO usually becomes relatively dry during the last half of the dry season (between early February and late April), with fallen dry leaves covering the forest floor (Figs. 12, 13), and is wet to fairly moist during the rest of the year (Figs. 7,8,9,10,11,12,13). The differences in the green density are quite notable between the dry and wet seasons (K. Nishida, personal observation 1998-2007). The average climatic data of the UCR campus between years 2001 and 2004 are as follows: minimum and maximum temperatures are 16°C and 25°C, respectively; average monthly rainfall in the dry season (December to April) was 23.1 mm; in the wet season (May to November) it was 235.6 mm (data from Centro de Investigaciones Geofísicas, UCR).

Some of the recent activities at the RELO are:

-Planting of Miconia calvescens (Melastomataceae) in the west (Fig. 10) and east sides by Proyecto Miconia in late 2002 to mid-2003.

-Installation of flagstones and pebbles along the trails in early 2006.

-Construction of a look-out area on the south bank of the Negritos River in early 2006.

-Officially associated with the Environmental Education Program by Comisión de Colecciones in the middle of 2006.

-Installation of a signpost at the main entrance (Fig. 7) at the end of 2006.

-Reforestation of west and northwest sectors with nearly 200 specimens of young trees. These trees were donated by Professor E. García and part of the planting was conducted by students of the Escuela Monterrey, in early to middle 2007.

-Initiation of topographical mapping in collaboration with the School of Topography, UCR, in March 2007.

-Conclusion of the Total Tree Inventory in the middle of 2007.

Leonelo Oviedo was a professor of the School of Biology at the UCR in the 1960s and 1970s. During that time he worked on establishing the Ecological Preserve, and he contributed more towards its development than anyone else. The Preserve was later named in his honor by Dr. Luis A. Fournier (José Francisco Di Stéfano 2005, pers. comm.), also a professor of the School of Biology.

Vertebrates: Some vertebrates recognized in the RELO are as follows. At least two individuals of the two-toed sloth, Choloepus hoffmanni, have lived more than 10 years and have reproduced –about five individuals were observed at one point–. The most abundant mammals are the bats that use the Preserve as refuge and feeding site and serve for plant pollination (J. M. Mora, pers. comm.). The variegated Squirrel, Sciurus variegatoides, has frequently been observed. An agouti, Dasyprocta punctata, was seen twice between 2000 and 2004 (K. Nishida & I. Nakamura, pers. obs.). One of the commonly seen birds is the Blue-crowned Motmot, Momotus momota. The Lineated Woodpecker, Dryocopus lineatus, and Grey-necked Wood-rail, Aramides cajanea, are new comers to the Preserve since 2002, though approximately 40% of what existed on campus ca. 20 years ago is no longer observed (G. Barrantes, pers. comm. 2007, in manuscript). A few reptiles and amphibians that stand out are: a coral snake, Micrurus nigrocinctus (Girard); a boa, Boa constrictor L.; a Plain wormsnake, Geophis hoffmanni (Peters); an Olive lizard eater, Mastigodryas melanolomus (Cope); a glass frog, Hyalinobatrachium fleischmanni (Boettger); a tree frog, Smilisca sordida (Peters); a lizard, Norops intermedius; and the toad Ollotis coccifer (Federico Bolaños, pers. comm. 2005).

Even in the midst of human "development" and habitat changes, several new and rarely collected insects have been discovered and described from inside and outside the RELO on the campus of UCR. For example, three new species of weevils with unusual biology (Prena & Nishida 2005; C. Lyal & K. Nishida, in preparation; J. Prena, pers. comm. 2003), four new parasitoid wasps with new biological data (Hanson & Nishida 2002, 2004, Fortier & Nishida 2004, Shaw & Nishida 2005), possibly a new species of katydid (P. Naskrecki, pers. comm. 2005), and two new records of rare-incollections moth species –Venadicodia caneti Epstein & Corrales (K. Nishida & M. Epstein, in preparation) and Filinota brunniceps (Felder & Rogenhofer) (D. Adamski & K. Nishida, in manuscript)–. At least one new species of skipper butterfly, Quasimellana, was collected at the RELO (L. R. Murillo, pers. comm. 2006). Some of these species are currently only known from the campus of UCR, i.e. are not known from anywhere else in Costa Rica. It is also noteworthy to mention the discovery of a rare Ascomycetes fungus that has only been found once in another part of the world (J. Carranza & J. Di Stefano, pers. comm. 2007).

Analysis

Plants (Figs. 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24, Table 1)

Table 1 shows the list of vascular plants resulting from the present inventory. There were some technical difficulties in identification of sterile plants of Araceae and Asteraceae, and Pteridophyta. The following summarizes Table 1: There were eight families of Pteridophyta with 14 species in approximately 14 genera; seven Gymnospermae with 10 species in eight genera; 26 Monocotyledoneae with 121 species in 84 genera; and 72 Dicotyledoneae with 286 species in 228 genera. Thus, the total species number was 432 in approximately 334 genera within 113 families. We recorded ca. 205 species in the RELO (excluding nursery garden). Of these 205 species, 64 species (ca. 31%) were present exclusively in the RELO, i.e. were absent in the nursery garden or on UCR campus. There were 117 species in the nursery garden and 33 species (ca. 28%) of these were found only on that site. On the rest of the campus indicated in figure 5, we recorded 317 species; 142 species (ca. 45%) of these were absent either from the nursery garden or the RELO.

Most of the plants on UCR campus (excluding the RELO), whether native or introduced, were planted as ornamentals. Consequently, only 57% (182 species) of the campus flora was composed of native Costa Rican species. In the RELO, 86% of flora (179 species) was native to Costa Rica; though not all these species were native to the studied site, i.e. were either manually planted or escaped from cultivation and arrived at the Preserve either before or after the preservation of the area as the RELO. Roughly one-third (59) of the 179 Costa Rican species naturally does not occur in the Preserve or in the Premontane Moist Forest habitat of the region. Most of these plants were composed of young cultivated trees, species that usually grow in secondary forests in lowland regions of Costa Rica. Regarding just the tree species of the Preserve, there were 36 native-to-region species, which is 17.6% of the RELO total flora. The 36 tree species account for approximately 30% of all native-toregion plants including shrubs and herbaceous species.

In the RELO, basically two floristic components were observed. One was composed of secondary growth herbs, shrubs, and trees, with a very few mature large vegetations which are survivors from the ancient forests of the region. Regarding the presence of the remnant large native trees, it appeared to be favored by the presence of the Negritos River, because most of these trees were found along the river banks. The other component was composed of various planted, introduced tree species from lowland and a smaller number from the highland of Costa Rica, as well as a few exotic tree species. Native-to-region tree species commonly occuring in the RELO were Stemmadenia litoralis (Apocynaceae), Cordia eriostigma (Boraginaceae), Cecropia obtusifolia (Cecropiaceae) (Fig. 23), Croton draco, Sapium glandulosum (Euphorbiaceae), Inga punctata, Lonchocarpus cf. oliganthus (Fabaceae), Licaria triandra, Persea caerulea (Lauraceae), Trichilia havanensis (Meliaceae), and Acnistus arborescens (Solanaceae) (Fig. 24). In contrast, Ficus cf. citrifolia (Moraceae) and Zanthoxylum rhoifolium (Rutaceae) were floristically considered rare in the Preserve. Other rare species in the RELO were: a terrestrial herb, Govenia cf. liliacea (Orchidaceae); a riparian herb, Hygrophila costata (Acanthaceae); an herbaceous climber, Torretia lappacea (Bignoniaceae); and two shrubs, Acalypha leptopoda (Euphorbiaceae) and Podachaenium eminens (Asteraceae). This last species once commonly occurred in urbanized areas of San José, though presently it is close to local extinction. Therefore, the Preserve may well be one of the last refuges for the species in this region. Currently, three individuals were recognized in the southwestern limit of the Preserve, indicating a possible recovery of a small population.

Most of the invasive plants found in the RELO consisted of introduced exotic ornamentals (e.g. Erythrina poeppigiana, Impatiens walleriana, Megaskepasma erythrochlamys, Syzygium jambos), weeds (e.g. Cyperus involucratus, Pennisetum purpureum) and some crops and fruit trees (especially Coffea arabica, Mangifera indica, and Eriobotrya japonica) which escaped from cultivation. In Costa Rica, the fast-growing, large, northern South American Erythrina poeppigiana trees are commonly planted as fence trees on farm lands and as shadow trees in coffee plantations. This species has been reproducing itself very successfully in the RELO where we have seen hundreds of saplings and germinating seeds, especially in the rainy seasons of the last two years. Monitoring and controlling all exotics and species that are not native to the region is necessary, especially when they become invasive and affect native flora and fauna. This could apply also to some of the native species to establish healthy conditions of the Preserve for its regeneration. For example, approximately 10 years ago thickets of Ipomoea santillanii were very abundant, covering most of the forest floor and hindering the growth of small trees, thus it was necessary to control (Di Stéfano 1996). At present it appears that a control of Chamaedorea costaricana is necessary since its thickets are covering the forest floor quite heavily in some parts of the Preserve. Another locally native species which is possibly invasive is Pseuderanthemum cuspidatum (Fig. 16).

Today the forest floor is more shaded than 10 years ago; hence, we must note that the flora and fauna of the Preserve changes as the forest grows. For example, the shrubs of Psychotria marginata (Rubiaceae) which grow in slightly open understory have slowly been weakening, wilting, and disappearing during the last few years. Also some drastic changes may occur as large trees fall and destroy the others, or small plants, especially occasional small herbs will suffer by the periodic trimming of the plants in open areas of the campus.

Butterflies and day-flying moths

Table 2 lists 203 species of butterflies and 20 species of day-flying moths thus far recorded in the RELO. The list also shows the year(s) in which the record is available in order to provide a measure of historical context and the up-to-datedness of the available records, as well as the times of the year in which the presence of each species adult has been confirmed. Our own study began in 1997, but for the sake of completeness we included the data available from several other sources as described in the materials and methods section. Unfortunately, however, dates of collecting were not always available in those cases. We have been able to confirm the presence of 13 species of Ithomiinae between 1997 and 2007, a far cry from the 29 species Stiles found in 1979 or 1980. Moreover, between 1975 and 1981, Stiles (pers. comm. 2005) observed 40 species of Ithomiinae, a number that approaches 80% of the total species known from Costa Rica. It should be noted, however, that these most likely include migrating species or strays rather than true residents (G. Stiles pers. comm., 2005), a caveat that applies equally to the rest of the Ithomiinae species we have found ourselves. Devries (1987) also mentions that this many species might be found in San José for this reason. Of particular interest among the records is Ithomia celemia, a species known to be one of the rarest of Costa Rican Ithomiinae. The nearest current habitat of this species is Rodeo (Montero-Moreno 2003; I. Nakamura, unpublished record, 2007). It is not inconceivable that this species was more common in the Central valley until its main habitats were lost.

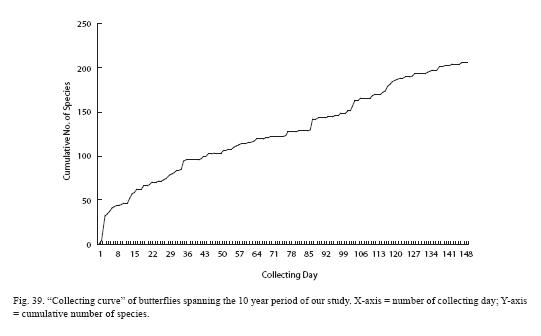

We present in Fig. 39 a "collecting curve" of butterflies spanning the 10 year period of our study (note that it does not include day-flying moths). Atypical shape of the curve has several causes. First, we counted any visit to the RELO as a collecting day, regardless of the length of the time spent or the weather condition. Second, when rearing of larvae or pupae ended with adults, the day of adult emergence was counted as a visit. Presence of a substantial number of species was first established through rearing, particularly in the early phase of our study, resulting in the slow rate of rise early in the curve. Third, our effort to inventory the Hesperiidae of the RELO did not begin in earnest until relatively late. In any event, the curve clearly indicates that our list is far from complete and that our effort needs to continue.

Generally speaking, the butterfly fauna of the RELO seems notable for the common occurrence of some species which are seldom encountered or at least much less common elsewhere. These include Synale cynaxa (Hesperiidae, Hesperiinae), the two Hesperocharis species (Pieridiae, Pierinae), and Catocyclotis adelina) (Riodinidae, Riodininae) (Fig. 33). None of these species appear in Fultons list (1966) or in Vega & Gloor (2001). It is possible that the relatively common occurrence of these species in the RELO simply reflects availability of uncommon host plants and other favorable conditions. Alternatively, these species may represent a remnant of the former fauna of the Central valley.

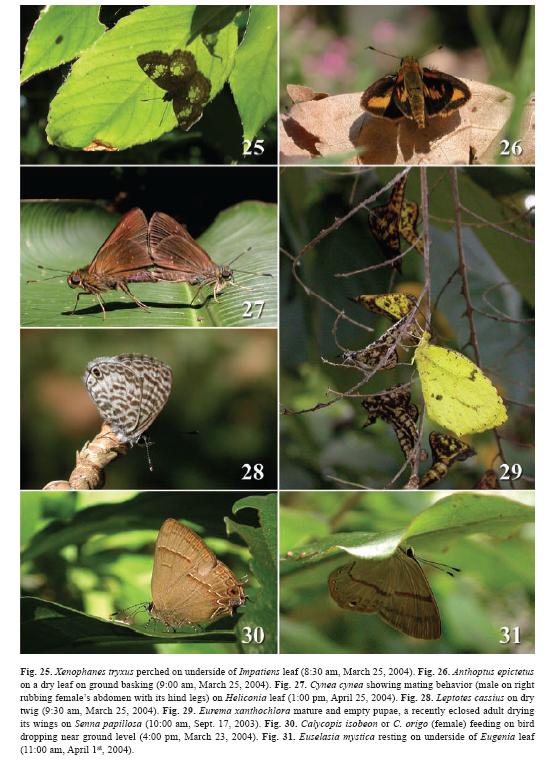

The following species were commonly seen in the RELO throughout the year: Greta morgane, Ithomia heraldica, I. patilla (Fig. 34) (Ithomiinae), Oxeoschistus tauropolis (Fig. 35), Pedaliodes manis, Hermeuptychia hermes (Satyrinae), and Heliconius erato (Fig. 38) (Heliconiinae). In almost every visit, at least one individual of these species was encountered along the trail. Other common species include Astraptes, Staphylus, Urbanus, Callimormus, Cynea (Fig. 27), Papias, Poanes (Fig. 26), and Saliana species in Hesperiidae; Eurema (Fig. 29) and Phoebis species in Pieridae; Calycopis (Fig. 30) in Lycaenidae; Calephelis and Catocyclotis (Fig. 33) in Riodinidae; Pteronymia notilla in Ithomiinae; Anthanassa ardys, Castilia griseobasalis (Fig. 36) in Nymphalinae; Dryas iulia, and Heliconius charithonia (Fig. 37) in Heliconiinae.

Some butterflies were observed on the following naturally occurring food sources: Some skippers (e.g. Pompeius pompeius (female) and Astraptes alardus) on bird dropping, Sinale cynaxa on flower nectar of Impatiens walleriana, Phoebis, some lycaenids (unidentified) and Thisbe lycorias on Inga vera (Fig. 20), Calycopis isobeon / origo (female) feeding on bird dropping (Fig. 30), Catocyclotis adelina (male) on flowers of Acnistus arborescens (Fig. 24), several ithomiines on bird droppings or carrion (decomposing insects), overripe Rivina humilis fruits (Fig. 18), and accumulated water in Heliconia flowers, Oxeoschistus tauropolis on sticky secretion on flower-fruit peduncles of Chamaedorea costaricana (Fig. 14), Pedaliodes manis on flower nectar of the Impatiens and decomposing flower of Monstera deliciosa on ground, Heliconius clysonymus on flower nectar of Hamelia patens (Fig. 21). The following species were caught on the flowers of Acnistus arborescens: Cynea sp.; Mucia zygia; Pompeius pompeius; Buzyges rolla; Ascia monuste; Hesperocharis costaricensis;

H. crocea; Strymon cestri; Calycopis isobeon / origo; Ziegleria syllis; and Thisbe lycorias. Those species caught in the plantain-banana traps, placed between 1 to 5 m above ground, are indicated in Table 2.

The well-known behavior of Hamadryas februa, perching head-down with the wings open or flying and producing clicking-sounds around the bare trunks of medium to large trees, has been seen on campus and commented on by casual observers (also from J. Monge-Nájera, pers. comm.).

Importance of the RELO

As stated earlier, the original purpose of establishing the RELO was to protect the area and restore a representative Premontane Moist Forest of the region. However, the current condition of the Preserve may be described as a mosaic of native, non-native-to-region, and exotic plants. Thus, it does not represent a forest truly composed of locally native species and is more like a botanical garden. One of the critical facts that seem to defy the concept of the Ecological Preserve is ongoing planting of trees that are not native to the region. Furthermore, some of those young trees were not even taxonomically identified at the time of planting, clearly diverging from the original purpose and worsening the conditions of the Preserve.

Data from 1991 show that 98% of the Premontane Moist Forest habitat in Costa Rica is deforested, i.e. only 2% remains as Premontane Moist Forest; this remaining tiny portion is composed of 265 fragmented areas with each patch averaging 0.3 km² in size (Sánchez-Azofeifa et al. 2001). The percentage and patch sizes are the smallest among all other life zones according to Holdridge (1967) classification. Sánchez-Azofeifa et al. (2001) state that "Forests are almost completely eliminated from the Tropical Moist Forest and Premontane Moist Forest life zones, and the level of fragmentation of remaining forests may be more advanced than previously thought." According to J. Lobo (pers. comm. 2007), the data compiled by the Fondo Nacional de Financiamiento Forestal (FONAFIFO 2005) indicate that merely ca. 4500 ha of the Premontane Moist Forest habitat in Costa Rica is still covered by forest, that is, ca. 0.003% of protected areas that include National Parks, Biological Reserves, and Wildlife Refuges, among others. This low percentage presumably resulted from the concentrated distribution of such life zone in the central part of Costa Rica, such as in the Valleys of Cartago, San Ramón, and especially in the Central Valley (Bolaños et al. 1999) where human "development" is prevalent. Therefore, reconditioning and preserving such forest habitat is even more important, including a small patch of green space in the Central Valley such as the RELO.

The small RELO preserve is under pressure from habitat fragmentation, air and water pollution, and invasion of non-native plants, requiring reconditioning to improve its ecosystem. On the other hand, it has been playing important roles for many organisms, and serving the needs of students and researchers. The RELO is likely to yield more new discoveries in addition to those we mentioned earlier, indicating its potential scientific value. It is probable that the ecological conditions of the RELO have been supported by other green areas surrounding the UCR campus and vice versa, especially the areas in Ciudad de la Investigación and Instalación Deportiva of the UCR, including "protected" areas along the rivers (Fig. 2). There are at least two important roles the Negritos Creek plays for the Preserve, namely 1) as a narrow biological corridor for living organisms (Di Stéfano et al. 1996) and 2) providing a fair amount of moisture for survival of organisms especially during the dry season.

While a larger connected protected area would be ideal (MacArthur & Wilson 2001, Laurence et al. 2006), fragmentation of natural habitat or green space seems inevitable in urban areas where social pressure dominates (Bertsch 2006); however, keeping or creating small preserves like the RELO may be the best current option that we can embrace. Two known projects are presently in progress in the city of San José. One is Proyecto Mariposas en San José, organized by Plan de Arborización Urbana (PLANARBU), Sección de Parques del Municipio, Municipalidad de San José (A. Solórzano, pers. comm. 2005). The other is Proyecto Plás conducted by Programa Bandera Azul Ecológica of Departamento de Educación Ambiental del Ministerio de Educación Pública and JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) in Costa Rica with Escuela República de Haití in San Sebastián de Paso Ancho (Proyecto Plás 2007). These two projects aim to recreate an environment suitable for butterflies and other organisms in the city of San José by planting trees that are locally native, as well as butterfly host plants and flowering plants that are also native. These projects and the existence of the RELO may hopefully slow down the process of species extinction to some extent, and help migratory species that fly through the Central valley (Haber 1993).

In addition to conservation of biodiversity and habitat, it is clear that green natural space in a city environment is important for many other reasons, e.g., it reduces city noise, provides better water retention to reduce flood frequency, and supplies better air quality (clean moist air) (Sukopp & Werner 1991, Nowak et al. 1997, Pickett et al. 2001 and references therein, Rudd et al. 2002, Chiesura 2004, Ruiz-Jaen & Mitchell 2006). Ongoing habitat destruction and fragmentation, as well as air and water pollution in the valley will undoubtedly have negative impacts even to the surrounding protected areas, e.g. El Zurquí region of Braulio Carrillo National Park and Zona Protectora El Rodeo.

In spite of the rapid and devastating deforestation of the Central valley in the past, which most likely was associated with coffee plantations in early 19th century, we still have some plant species native to the region which can be used to restore and improve Premontane Moist Forest. We hope that this study will serve as a basis for further research in the RELO and its surrounding habitats, and for monitoring our environment.

Acknowledgments

We thank José Fco. Di Stéfano G. for the permission to conduct this study in the RELO, providing literature and valuable information, and for reviewing the manuscript; Elizabeth Heffington for reviewing the draft; F. Gary Stiles for sharing the unpublished data on Ithomiinae and comments on the manuscript; Paul E. Hanson for sharing the butterfly list and revision of the manuscript; vladimir Jiménez Salazar for providing aerial photo of San Pedro and comments on the geographical area of the Central valley; Jorge Lobo and Patricia Ortiz for sharing unpublished data, on the forest covertures and the map of the RELO, respectively. Julián Monge-Nájera, José Manuel Mora, Gilbert Barrantes, Federico Bolaños, Julieta Carranza, Luis Ricardo Murillo and Cesar Sánchez kindly provided information on the organisms of the RELO and campus. Nakamuras collecting activity was conducted under research permits issued by SINAC/MINAE through 2004-07, and for this he thanks Javier Guevara of MINAE and Mario Posla. For identification of Lycaenidae, Riodinidae, and Hesperiidae, the staff of the U.S. National Museum, the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., provided invaluable assistance, in particular, Robert Robbins, Donald Harvey, Jason Hall, and John Burns. George Austin and Andy Warren at the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity, Gainesville, Florida, were particularly helpful in identifying some of the difficult Hesperiids. The climatic data were provided by Centro de Investigaciones Geofísicas, UCR. Adrián Solórzano and Municipalidad de San José provided information about PLANARBU. Day-flying arctiid moths and some of the skippers were identified by Bernardo Espinoza and Andrew D. Warren, respectively. Some Asteraceae and Cyperaceae were identified by Jorge Gómez-Laurito, and Phlebodium fern was identified by Alexander Rojas.

Resumen

Por ser el área más poblada del país, el Valle Central de Costa Rica perdió su hábitat natural; lo poco que queda ha sido alterado en grados variados. Sin embargo, se han realizado algunos estudios para evaluar la necesidad de conservación en esta área. Se presentan inventarios preliminares de plantas, mariposas y polillas diurnas de la Reserva Ecológica Leonelo Oviedo (RELO); una pequeña reserva de bosque húmedo premontano en del campus de la Universidad de Costa Rica, ubicado en la parte urbanizada del Valle. Las mariposas diurnas son uno de los mejores bio-indicadores de la salud del hábitat, porque son muy sensibles a los cambios del ambiente y están estrechamente ligadas a la flora local. Se presenta también una descripción de los caracteres físicos y la historia de la RELO, con ilustraciones. Se identificaron aproximadamente 432 especies de ca. 334 géneros en 113 familias de plantas. Sin embargo, solamente 57% de ellas son especies nativas del bosque húmedo premontano de la región; el resto son especies exóticas o introducidas en su mayoría desde tierras bajas. Se han registrado más de 200 especies de mariposas diurnas en seis familias, incluyendo Hesperiidae.

Palabras clave: biodiversidad, conservación biológica urbana, polillas diurnas, Lepidoptera, bosque húmedo premontano, Costa Rica.

Received 15-IV-2008. Corrected 15-VIII-2009. Accepted 25-IX-2009.

References

Andrade-C., M.G. 1998. Utilización de las mariposas como bioindicadoras del tipo de hábitat y su biodiversidad en Colombia. Rev. Acad. Colombiana Cien Ex. Fís. Natur. 22: 407-421. [ Links ]

Austin, G.T. & T.J. Riley. 1995. Portable bait traps for the study of butterflies. Trop. Lepid. 6: 5-9. [ Links ]

Beccaloni, G.W., Á.L. viloria, S.K. Hall & G.S. Robinson. 2008. Catalogue of the Hostplants of the Neotropical Butterflies / Catálogo de las Plantas Huésped de las Mariposas Neotropicales. m3m-Monografías Tercer Milenio, volume 8. Zaragoza, Spain: Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa (SEA)/Red Iberoamericana de Biogeografía y Entomología Sistemática (RIBES)/ Ciencia y Tecnología para el Desarrollo (CYTED)/ Natural History Museum, London, U. K. (NHM)/ Instituto venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas, venezuela (IVIC). [ Links ]

Bertsch, F. 2006. El Recurso tierra en Costa Rica. Agronomía Costarricense 30: 133-156. [ Links ]

Bolaños, R., V. Watson, & J. Tosi. 1999. Mapa ecológico de Costa Rica (Zonas de vida). Centro Científico Tropical, Sistema de Información Geográfica, San José, Costa Rica. [ Links ]

Brown Jr., K.S. 1987. Biogeography and evolution of the Neotropical butterflies, p. 66-104. In T. C. Whitmore & G.T. Prance (eds.). Biogeography and Quaternary History in Tropical America. Clarendon, Oxford, England. [ Links ]

Brown Jr., K.S. 1991. Conservation of Neotropical environments: insects as indicators, p. 349-404. In N.M. Collins & J.A. Thomas (eds.). The Conservation of Insects and their Habitats. Academic, New York, USA. [ Links ]

Brown Jr., K.S. 1996. The use of insects in the study, inventory, conservation and monitoring of biological diversity in Neotropical habitats, in relation to traditional land use systems, p. 128-149. In S.A. Ae, T. Hirowatari, M. Ishii & L.P. Brower (eds.). Decline and Conservation of Butterflies in Japan. Lepidoptera Society of Japan, Yadoriga, Osaka [special issue], Japan. [ Links ]

Brown Jr., K.S. 1997. Diversity, disturbance, and sustainable use of Neotropical forests: insects as indicators for conservation monitoring. J. Insect Conserv. 1: 25-42. [ Links ]

Cascante M., A. & A. Estrada Ch. 2001. Composición floristica y estructura de un bosque húmedo premontano en el valle Central de Costa Rica. Rev. Biol. Trop. 49: 213-225. [ Links ]

Chacón, E. & G. Saborío-R. 2006. Análisis taxonómico de las especies de plantas introducidas en Costa Rica. Lankesteriana 6: 137-145. [ Links ]

Chiesura, A. 2004. The role of urban parks for the sustainable city. Landscape Urban Plann. 68: 129-138. [ Links ]

Daily, G.C. & P.R. Ehrlich. 1995. Preservation of biodiversity in small rainforest patches: Rapid evaluations using butterfly trapping. Biodiversity Conserv. 4: 35-55. [ Links ]

Devries, P.J. 1987. The Butterflies of Costa Rica and their Natural History: volume I: Papilionidae, Pieridae, Nymphalidae. Princeton University, New Jersey, USA. [ Links ]

Devries, P.J. 1997. The Butterflies of Costa Rica and their Natural History: volume II: Riodinidae. Princeton University, New Jersey, USA. [ Links ]

Di Stéfano, J.Fco., V. Nielsen, J. Hoomans, & L.A. Fournier. 1996. Regeneración de la vegetación arbórea en una pequeña reserva forestal urbana del nivel premontano húmedo, Costa Rica. Rev. Biol. Trop. 44: 575-580. [ Links ]

Fortier, J. & K. Nishida. 2004. A new species and host association biology of Neotropical Compsobraconoides Quicke (Hymenoptera: Braconidae). J. Hym. Res. 13: 228-233. [ Links ]

Fulton, M. 1966. A list of Lepidoptera collected in Costa Rica. Rev. Biol. Trop. 14: 287-292. [ Links ]

Haber, W.A. 1993. Seasonal migration of monarchs and other butterflies in Costa Rica. Nat. Hist. Mus. Los Angeles County, Sci. Ser. 38: 201-207. [ Links ]

Hansson, C. & K. Nishida. 2002. A new species of Pediobius (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) from Epilachna (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) in Costa Rica. Rev. Biol. Trop. 50: 121-125. [ Links ]

Hansson, C. & K. Nishida. 2004. A new species of Emersonella (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae), parasitoid on weevil eggs (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), from Costa Rica. Zootaxa 607: 1-6. [ Links ]

Herrera S., W. & L.D. Gómez P. 1993. Mapa de Unidades Bióticas de Costa Rica. Escala 1:685.000. US Fish & Wildlife Service - TNC - INCAFO - CBCCR - INBio-Fundación Gómez - Dueñas. San José, Costa Rica. [ Links ]

Holdridge, L.R. 1967. Life zone ecology. Tropical Science Center, San José, Costa Rica. [ Links ]

Holloway, J.D. & P.D.N. Herbert. 1979. Ecological and taxonomic trends in Macrolepidopteran host plant selection. Biol. J. Linnean Soc. 12: 229-251. [ Links ]

ICT. 2007. Conozca Costa Rica 2. Instituto Costarricense de Turismo, oficina en Japón (ed.). Asociación para la Conservación de la Naturaleza Japón-Costa Rica, Tokyo, Japan. [ Links ]

Janzen, D.H. & W. Hallwachs. 2007a. Conservación en Costa Rica desde la frontera hasta la biblioteca moderna: el costo y la oportunidad. Conference: March 22, 2007, Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica. [ Links ]

Kremen, C. 1994. Biological inventory using target taxa. A case study of butterflies of Madagascar. Ecol. Applic. 4: 407-422. [ Links ]

Lamas, G. (ed.). 2004. Checklist part 4A. Hesperioidea-Papilionoidea. In: J.B. Heppner (ed.). Atlas of Neotropical Lepidoptera. Vol. 5A. Assoc. for Trop. Lepid. / Scientific Publ., Gainesville, USA. [ Links ]

Laurence, W.F., H.E. M. Nascimento, S.G. Laurance, A. Andrade, J.E.L. S. Ribeiro, J.P. Giraldo, T.E. Love-joy, R. Condit, J. Chave, K.E. Harms, & S. DAngelo. 2006. Rapid decay of tree-community composition in Amazonian forest fragments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 19010-19014. [ Links ]

León, J. 1948. Land utilization in Costa Rica. Geographical Rev. 38: 444-456. [ Links ]

MacArthur, R.H. & E.O. Wilson. 2001. The Theory of Island Biogeography. Princeton University, New Jersey, USA. [ Links ]

Mielke, O.H.H. 2005. Catalogue of the American Hesperioidea: Hesperiidae (Lepidoptera). 6 Vols, pp. xiii + 1536, Sociedade Brasileira de Zoologia, Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil. [ Links ]

Montero-Moreno, J.R. 2003. A new locality for a rare Ithomiine butterfly, Ithomia celemia plaginota, in Costa Rica. News Lepid. Soc. 45: 115. [ Links ]

Murillo, L.R. & K. Nishida. 2003. Life history of Manataria maculata (Lepidoptera: Satyrinae) from Costa Rica. Rev. Biol. Trop. 51: 463-470. [ Links ]

New, T.R., R.M. Pyle, J.A. Thomas, C.D. Thomas & P.C. Hammond. 1995. Butterfly conservation management. Annu. Rev. Entom. 40: 57-83. [ Links ]

Nowak, D.J., J.F. Dwyer, & G. Childs. 1997. Los beneficios y costos del enverdecimiento urbano, p. 17-38. In L. Krishnamurthy & J. Rente Nascimento (eds.). Áreas verdes urbanas en Latinoamérica y el Caribe. Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo, WashingtonD.C. , USA. [ Links ]

Ortiz Barriga, P.G. 2002. Historia natural, sitios de apareamiento, comportamiento sexual y posible función de la alimentación nupcial en Ptilosphen viriolatus (Diptera: Micropezidae). Tesis de Maestría, Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica. [ Links ]

Pearson, D. 1994. Selecting indicator taxa for the quantitative assessment of biodiversity. Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. London 354: 75-79. [ Links ]

Pickett, S.T.A., M.L. Cadenasso, J.M. Grove, C.H. Nilon, R.v. Pouyat, W.C. Zipperer, & R. Costanza. 2001. Urban ecological systems: Linking terrestrial ecological, physical, and socioeconomic somponents of metropolitan areas. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 32: 127-157. [ Links ]

Prena, J. & K. Nishida. 2005. Thanius biennis (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Baridinae), a new gall-inducing weevil with a two-year lifecycle from Costa Rica. Beitr. Entom. 55: 141-150. [ Links ]

Rudd, H., J. Vala, & V. Schaefer. 2002. Importance of backyard habitat in a comprehensive biodiversity conservation strategy: A connectivity analysis of urban green spaces. Restor. Ecol. 10: 368-375. [ Links ]

Ruiz-Jaén, M. & T. Mitchell. 2006. An integrated approach for measuring urban forest restoration success. Urban For. Urban Greening 4: 55-68. [ Links ]

Sánchez-Azofeifa, G.A., R.C. Harriss, & D.L. Skole. 2001. Deforestation in Costa Rica: A quantitative analysis using remote sensing imagery. Biotropica 33: 378-384. [ Links ]

Shaw, S.R. & K. Nishida. 2005. A new species of gregarious Meteorus (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) reared from caterpillars of Venadicodia caneti (Lepidoptera: Limacodidae) in Costa Rica. Zootaxa 1028: 49-60. [ Links ]

Shuey, J.A. 1997. An optimized portable bait trap for quantitative sampling of butterflies. Trop. Lepid. 8: 1-4. [ Links ]

Smith, N., S.A. Mori, A. Henderson, D.W. Stevenson, & S.v. Heald. 2004. Flowering plants of the Neotropics. Princeton University, New Jersey, USA. [ Links ]

Solis, M.A. & M.G. Pogue. 1999. Lepidopteran biodiversity: patterns and estimators. Amer. Entom. 45: 206-212. [ Links ]

Sparrow, H.R., T.D. Sisk, P.R. Ehrlich, & D.D. Murphy. 1994. Techniques and guidelines for monitoring neotropical butterflies. Conserv. Biol. 8: 800-809. [ Links ]

Sukopp, H. & P. Werner. 1991. Naturaleza en las ciudades. Desarrollo de flora y fauna en áreas urbanas. Monografías de la Secretaría de Estado para las Políticas del Agua y el Ambiente. Ministerio de Obras Públicas y Transportes, Madrid, España. [ Links ]

Vega A., G. & P. Gloor. 2001. Lista preliminar de las mariposas diurnas (Hesperioidea: Papilionoidea) de la Zona Protectora El Rodeo, Ciudad Colón, Costa Rica. Brenesia (55-56): 101-122. [ Links ]

Vega, L.M. & J. valerio. 2002. Análisis del crecimiento urbano del área metropolitana de San José. Tesis Lic. Ciencias Geográficas. Universidad Nacional, Heredia, Costa Rica. [ Links ]

Wahlberg, N., M.F. Braby, A.v.Z. Brower, R. de Jong, M.-M. Lee, S. Nylin, N.E. Pierce, F.A.H. Sperling, R. vila, A.D. Warren & E. Zakharov. 2005. Synergistic effects of combining morphological and molecular data in resolving the phylogeny of butterflies and skippers. Proc. Royal Soc. B 272: 1577-1586. [ Links ]

Internet references

FONAFIFO. 2005. Fondo Nacional de Financiamiento Forestal. Biodiversidad.(Downloaded: October, 2007, http://www.sirefor.go.cr/biodiversidad.html) [ Links ]

DigitalGlobe. 2007 & 2009. Google Earth. (Downloaded August 20, 2007 & October 3, 2009, http://earth. google.com/intl/en/) [ Links ]

INBio. 2004. 2004 Memoria INBio annual report. (Downloaded: August 10, 2007, http://www.inbio.ac.cr/pdf/ Memoria2004.pdf) [ Links ]

INBio. 2005. 2005 Memoria INBio annual report. (Downloaded: August 10, 2007, http://www.inbio.ac.cr/es/ memorias/memoria2005/memoria2005-es.pdf) [ Links ]

INBio. 2007. Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad. Costa Rica. (Downloaded: August 10, 2007, http://www. inbio.ac.cr/es/default.html) [ Links ]

Janzen, D.H. & W. Hallwachs. 2007b. Database homepage. Caterpillars, pupae, butterflies and moths of the ACG. (Downloaded: March 18, 2007, http://janzen.sas. upenn.edu/caterpillars/database.lasso). [ Links ]

Missouri Botanical Garden (MBG) 2007. Tropicos.org. Missouri Botanical Garden (W3TROPICOS Specimen Database). (Downloaded: August 30, 2007, http://mobot.mobot.org/W3T/Search/vast.html) [ Links ]

Programa Estado de la Nación (Costa Rica). 2006. Resumen duodécimo informe Estado de la Nación en Desarrollo Humano Sostenible / Programa Estado de la Nación. 64 pp. (Downloaded: October 17, 2007, http://www.estadonacion.or.cr/Info2006/prensa/Resumen_informe12.pdf) [ Links ]

Proyecto Plás. 2007. Agencia de Cooperación Internacional del Japón -Oficina de JICA en Costa Rica. (Downloaded: June 30, 2007, http://www.lrsarts.com/ plas/index.html) [ Links ]