Introduction

Cancer is one of the leading causes of mortality and one of the most important burdens on healthcare systems and communities globally. It is responsible for more than 10 million deaths worldwide (Siegel et al., 2022). One of the most common types of cancer with a high mortality rate is breast cancer with 11.7% of newly diagnosed cases in 2020. It is considered one of the deadliest cancers in all sexes, just behind lung, colorectal, liver, and stomach cancer (Sung et al., 2021). Studies have shown that the risk for breast cancer is due to a combination of factors such as age, genetic mutation, estrogen level, reproductive history, family history, prolonged exposure of mutagenic agents, and unhealthy lifestyle (Sun et al., 2017, Wu et al., 2018 Cancer cell growth is a dynamic process that can influence or be influenced by the immune system’s response. The immune system should recognize and eliminate it because it presents unique antigens on its surface recognizable by the immune cells (Esquivel-Velázquez et al., 2015, Ozga et al., 2021, Pandya et al., 2016). Sever al studies have revealed that the immune system prevents cancer growth and progression through anti-tumor activities mediated by both innate and adaptive immune cells such as NK cells, macrophages, cytotoxic T cells, and helper T cells, as well as various cytokines and chemokines (Ghoshdastider et al., 2021, Henke et al., 2020).

The spleen regulates immune responses by maintaining lymphocyte populations and directing them to target tissues, including tumors (Lewis et al., 2019). In cancer, cytotoxic T cells are crucial but often suppressed by regulatory T cells (Tregs), which promote immune tolerance via IL-10 and TGF-β, leading to a poorer prognosis Li et al., 2020; Togashi et al., 2019; Ohue and Nishikawa, 2019). Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), another key immune component, can either support anti-tumor activity through pro-inflammatory cytokines (M1-like) or promote tumor progression via anti-inflammatory signals (M2like), the latter being predominant in many cancers (Yu et al., 2019; Cendrowicz et al., 2021). Similarly, Th17 cells and their main cytokine IL-17 show dual roles, enhancing cytotoxic responses or driving tumor angiogenesis (Asadzadeh et al., 2017; Karpisheh et al., 2022). B cells may also contribute to tumor progression by modulating TAM polarization and collaborating with Tregs, M2 macrophages, and N2 neutrophils to suppress anti-tumor immunity (Fridman et al., 2021; Gun et al., 2019).

Chemotherapy has been widely used as a definitive treatment for various cancers, including breast cancer. One of the most commonly used chemotherapy agents is cisplatin, a nonspecific bifunctional alkylation agent resulting in a cross-linked inter-strand intra-strand bond of DNA. Its side effects include bone marrow suppression, kidney, nerve, and other organ damage. Oxidative stress from cisplatin radical metabolites could cause severe kidney damage. Other cisplatin adverse effects include nausea and vomiting, hepatotoxicity, retinopathy, neurotoxicity, and respiratory distress (Ghosh, 2019, Lee et al., 2020). Meanwhile, herbal medications derived from medicinal plants contain active components that potentially substitute or assist combined treatment. Phytochemical substances in herbal medicines have antioxidant and anti-cancer effects. Compared to synthetic pharmaceuticals, it is suggested that herbal treatment has fewer adverse effects (Lin et al., 2020).

Herbal medicine development is one of the alternative treatments for ailments from infections to cancer. Different herbal plants are then combined to improve their medicinal potency. Cheral is an herbal medication made from medicinal plants, including white turmeric rhizome (Curcuma zedoaria) and the chamber bitter (Phyllanthus niruri). The combination of the two plants has diverse chemicals that improve its efficacy as an alternative cancer treatment. The flavonoid content of both sources has been demonstrated to have anti-cancer action and antioxidant properties. Antioxidants have been shown to reduce reactive oxygen species (ROS) and boost the immune system (Willenbacher et al., 2019). The chamber bitter extract was found to have anti-inflammatory properties since it reduced the production of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β. It also promotes apoptosis in lung cancer cells in vitro (Jantan et al., 2019, Saahene et al., 2021). Also, the curcuminoid in white turmeric rhizome can suppress the growth of ovarian cancer (Pourhanifeh et al., 2020).

Although prior studies have shown the individual potential of these plants, little is known about their combined immunomodulatory effects. Our previous research demonstrated that combining C. zedoaria and P. niruri had immunosuppressive and ameliorative effects in a breast cancer model, reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines and balancing immune cells (Putra et al., 2024). Building on this, our current study investigates the immunomodulatory and therapeutic effects of Cheral extract in a DMBA-induced breast cancer mouse model, focusing on dose-response and mechanistic insights, particularly on macrophages, Th17 cells, regulatory T cells, and B lymphocytes. This present study employed DMBA to induce breast cancer due to its established ability to initiate mammary tumors via DNA adduct formation and estrogen receptor pathways. DMBA remains a cost-effective, immunocompetent model ideal for testing herbal therapies, unlike xenografts or transgenic models that require immunodeficient hosts or complex facilities (Abba et al., 2016).

Methodology

Animal model description and experimental design

The 7-8 week-old female BALB/c mice were used in the study. The pathogen-free mice were obtained from the Integrated Research and Testing Laboratory, Gadjah Mada University. Mice typically weigh between 25 and 30 grams. They were acclimated for one week before being treated. A completely randomized design was selected for the investigation. Mice were divided into six groups: vehicle group, DMBA group, cisplatin treatment with a dose of 3 mg/kg BW, Cheral dose treatment of 1.233 mg/kg BW (D1), 2.466 mg/kg BW (D2), and 4.923 mg/kg BW (D3). Each treatment included four replications, and the total number of mice utilized in this study was 24. Mice were housed in cages and treated in a designated area for experimental animals. The room was maintained at ambient temperature with a 12-hour light/dark cycle. The husks in the cages were changed daily to keep them clean. Every day, they were given standard food and water, ad libitum. The Research Ethics Committee of Universitas Brawijaya determined that the treatment and support of experimental animals met ethical standards, as evidenced by a certificate of ethical appropriateness number of 925-KEP-UB.

Carcinogen induction using DMBA

To initiate cancer development, 8-week-old mice were treated with DMBA (Tokyo Chemical Industry, Japan). Following our previous study, DMBA was used at a 0.015 mg/kg body weight and mixed with corn oil (Putra et al., 2024). Around the areola, DMBA was injected under the skin six times, one week apart. The volume of DMBA injected was proportional to each mouse’s weight. Palpation methods were used to examine the development of nodules in mice.

Cheral and cisplatin treatment

Mice injected with DMBA for six weeks were given Cheral extract (PT. Ismut Fitomedika Indonesia, Makassar), except for the healthy control. Cheral was diluted in distilled water before being administered. The cisplatin (Dankos Farma, Indonesia) was administered intraperitoneally after being dissolved in PBS solution, injected seven times in 14 days, at two-day intervals. The volume of cheral and cisplatin administered to the mice was determined by weighing their body mass.

Flow cytometry analysis

Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and the ventral region was sterilized with 70% alcohol before dissection. The spleen was removed, washed twice with PBS, and homogenized using a syringe base. The homogenate was suspended in 6 mL PBS and centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 5 minutes at 10 °C. The pellet was resuspended in 1 mL PBS, and 50 μL was transferred to a microtube, diluted with 500 μL PBS, and centrifuged again under the same conditions. The final suspension was adjusted to 1 × 106 cells/mL. After extracting the supernatant, the pellet was homogenized with 50 μl of extracellular antibody coloring. As extracellular antibodies, anti-CD11b, anti-CD4, anti-CD25, and anti-B220 (BioLegend, USA) were used. The samples were then incubated in the dark at 40°C for 20 minutes. 50 μl of Cytofix was applied to the sample (BioLegend, USA). The samples were then incubated for 20 minutes in the dark at 40°C before mixing with 500 μl of washperm (BioLegend, USA). The sample was then centrifuged at 2,500 rpm for 5 minutes at 10oC. The pellets were then incubated for 20 minutes at 40°C with an intracellular antibody, specifically anti-IL17 and anti-TGF-β, then added to 400 μl of PBS. After that, the samples were put in a cuvette and analyzed using a FACSCaliburTM (BD Biosciences).

Data analysis

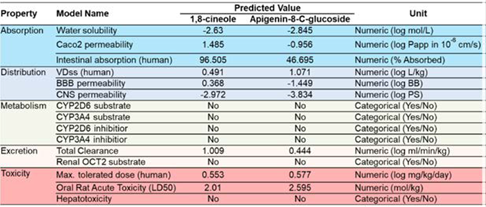

Compound-protein interaction analysis was conducted using the STRING database (https://string-db.org/). Target protein prediction was performed using the SwissTargetPrediction web server (http://www. swisstargetprediction.ch/). For Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity profiling, the pkCSM web server was utilized (https://biosig.lab.uq.edu.au/pkcsm/). The BD Cell Quest ProTM software examined the flow cytometry data. For the statistical analysis, SPSS version 20 for Windows was used. A one-way ANOVA test with a value α = 5% was performed. The Tukey Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test was employed to determine significantly level of treatment group.

Analysis and results

Cheral extract suppress the CD-11b+IL-17+ macrophages into a normal level

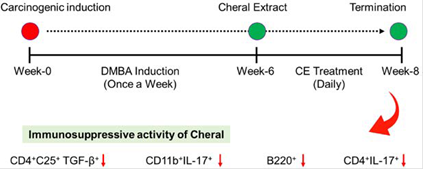

This study demonstrated that cheral extract exerts potential immunomodulatory activity in mouse breast cancer model. B Several immune cell expressions evaluated in this study showed a reduction trend after cheral extract administration (Figure 1).

Note: derived from research.

Figure 1 A schematic picture showed how cheral extract attenuates the mouse immune system to a normal level after being induced by carcinogen, DMBA.

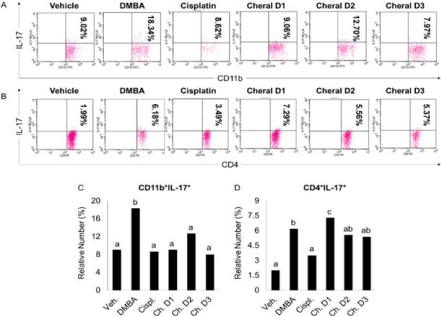

More specifically, DMBA induction significantly promotes the expression of CD-11b+IL-17+ macrophages compared to the vehicle group (Figure 2A and 2C).

Note: derived from research.

Figure 2 The immunosuppressive effects of cheral extract toward CD11b+IL-17+ macrophages (A and C) and CD4+IL-17+ T helper 17 cells (B and D) in DMBA-induced mice. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. Different alphabetic characters on the graph indicate a substantial difference.

Note: derived from research.

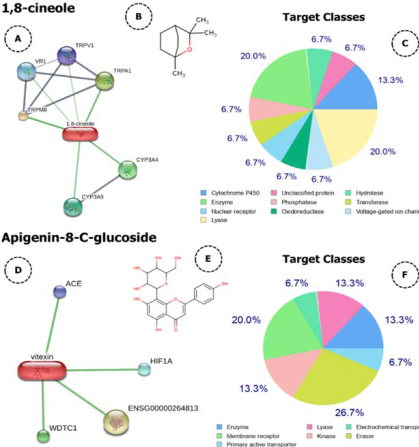

Figure 3 Compounds-proteins interaction network analysis (A and D), chemical structure (B and E), and target protein (C and F) of cheral’s bioactive compounds.

It is postulated that a higher number of M2 macrophages is thought to be correlated with a higher concentration of cytokines released by tumor cells and immune cells, particularly Th2 and Treg cells in TME, such as IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13, which drive macrophages polarization toward M2 phenotype (Lis-López et al., 2021, Saeedifar et al., 2021). It is suggested that higher Th2 and Tregs, which drive M2 polarization, indicate that cancer in the model has reached the escape phase in the immunoediting process (Ozga et al., 2021, Togashi et al., 2019).

This macrophage subtype has decreased tumor antigen-presenting capacity, reducing their pro-inflammatory potential and strongly shifting their attributes toward anti-inflammatory (Zhou et al., 2017). They also promote tumor growth by producing numerous growth factors such as PDGF and TGF1, forming a positive feedback loop between cytokines and tumor cell factors such as IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, MDF, TGF1, and PGE2 (Liu et al., 2021).

M2 phenotype macrophages are critical for tumor-related vasculature development, in which neo-vessels sprout from existing blood vessels or by proliferation, motility, and accumulation of vascular endothelial cells. Rapid tumor progression resulted in hypoxic zones, which induced the production of IL-4 and IL-10, boosting the recruitment and polarization of M2 type macrophages (Raggi et al., 2017). It may also aid tumor cells in acquiring a signature that allows them to activate and alter stromal characteristics to support malignancies (Liu et al., 2021). Combined with DMBA-induced oxidative stress through binding with cytochrome P-450, creating a covalent adduct with DNA, further driving the M2 cells’ recruitment and proliferation (Mazambani et al., 2019).

The cisplatin group showed the lowest results among the cancer-induced groups. To this date, there is no clear indication of the effect of cisplatin on M2 cells’ activation and activity. According to research, giving cisplatin might boost the ability of tumor cell lines to stimulate IL-10-producing M2 macrophages, which showed higher levels of active STAT3 owing to tumor-produced IL-6 and lower levels of activated STAT1 and STAT6 due to tumor cell PGE2 production (Dijkgraaf et al., 2013). However, newer studies suggest that the decreased number of M2 cells is caused by cisplatin’s favoring the M2-phenotype and further decreasing the population of M2-macrophages in the TME (Roux et al., 2019, Zhu et al., 2020). Meanwhile, a reduced number of M2 cells may imply a lesser amount of cancer cells that attract macrophages. Two bioactive constituents of cheral, linalool, and 1,8-cineol are considered to reduce cancer cell viability without harming normal cells (Gharge et al., 2021, Rodenak-Kladniew et al., 2020). The reduction in the amount of cancer cells may also result in a reduction in the cytokines that attract and encourage M2 macrophage growth. Furthermore, as a predictive study, we showed that both 1,8-cineole and apigenin-8-c-glucosidase, which were dominantly found in cheral extract, can be developed as drug candidate because of their broad spectrum of target proteins (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

•Cheral extract reduce the CD4 + IL-17 + T helper 17 cells

Similarly, with the macropahage’s population, the expression of CD4+IL-17+ in DMBA group was significantly increased compared to the vehicle group (Figure 2B and 2D). This result was in line with another study that also observed an increasing high expression of IL-17 by Th17 in breast tumor tissue. IL-17 is hypothesized to indirectly stimulate tumor cell growth and proliferation by boosting microvessel formation and density in the tumor region. Furthermore, tumor-infiltrating Th17 cells and IL-17 increased the granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) production, resulting in the recruitment of immature myeloid cells into the tumor microenvironment (Zhao et al., 2020). IL-17 has been shown to increase tumor aggressiveness in individuals with invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) by inducing angiogenic factors such as the chemokine CXCL8, MMP-2, MMP-9, and VEGF. Another key cytokine generated by Th17 cells, IL-22, has been shown to increase the rate of angiogenesis, proliferation, and tumorigenesis by promoting the expression of Pin1 and MAP3K8, which is directly associated to cancer development (Karpisheh et al., 2022). During cancer growth, Th17 cells also control CXCL1 expression. CXCL1 expression on tumor cells and binding to the CXCR2 receptor have been shown to activate the NF-κB/AKT pathway, resulting in metastasis, angiogenesis, growth, and development of breast cancer (Ma et al., 2018). CXCL1 and CXCL5 production from tumor cells induced by IL17 increases the suppressive action of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) on T cells by upregulating arginase (Arg), indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), and prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase-2 (COX-2) expression (Welte & Zhang, 2015). As a result, the rise in IL-17 in the cancer-positive group corresponded to a significant increase in the number of IL-17-producing cells in the tumor site (Ge et al., 2020).

The decreasing number of Th17 cells in the cisplatin group is in line with a clinical study of cervical cancer patients in various stages, which stated that all groups showed a decreasing number of circulating Th17 cells after chemoradiotherapy using cisplatin (Liu et al., 2021). However, the exact mechanism of cisplatin work in Th17 cells was unclear. We suspect the effect is similar to other types of immune cells because of its lymphopenic effect and its activity that binds to the target DNA via the Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) transcription factor (Sasaki-Kudoh et al., 2017). Activated AhR ligands migrate to the nucleus with the presence of ARNT cofactors, then bind to a specific DNA-recognition site in the AhR-responsive gene and promote gene transcription, causing DNA aggregation that can eventually induce cell death (Larigot et al., 2018).

According to the results, compared to the cancer control group, two cheral dosage groups (D2 and D3) demonstrated fewer Th17 cells in the mice’s spleen with no significant change between those treatment groups and DMBA-induced control. In comparison, the D1 group possessed more IL-17 and Th17 cells. These findings vary from previous research that suggests that providing bioactive chemicals may reduce the amount of Th17 and IL-17 expressed in cancer. Although the specific mechanism is unknown, trans-chalcone from C. zedoaria is predicted to suppress Th17 cytokines in UV-induced cancer mice (Kim et al., 2021). P. niruri’s wogonin has been shown to block T cell development into Th17 cells (Liao et al., 2021).

Cheral treatment can improve mouse models’ immune responses to cancer to the point that they no longer require significant levels of IL-17, as evidenced by a decrease in the proportion of macrophages secreting IL-17 cytokines in all Cheral therapy groups. Cheral’s polyphenols and flavonoids work as antioxidants, reducing free radical activity in cancerous cells (Kopustinskiene et al., 2020). Furthermore, they possess anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, and anti-hepatotoxic properties that are responsible for reducing the relative number of macrophages that generate IL-17 cytokines in the Cheral group treatment. Besides, a study showed that the P. niruri extract, the main component of cheral, could inhibit urokinase-type plasminogen activator and MMP-2 enzyme activity, and ERK1/2 activation (Saahene et al., 2021). Some study also suggests that IL-17 secreted by Th17 could have anti-tumor rules by increasing the population of cytotoxic IFN-γ+CD4+ and IFN-γ+CD8+ T cells in ovarian cancer, signals apoptosis via receptor-mediated caspaase activation, enhanced CD107a, TNF, IFN-γ, perforin, NKp46, NKG2D, and NKp44 expression in NK cells, and instructs the innate and adaptive immune system to become cytotoxic (Vitiello and Miller, 2019). It is also report ed that IL-17 prevented the accumulation of MDSCs in breast cancer tumor tissue by activating STAT3 signaling (Karpisheh et al 2022). Unfortunately, we cannot find any explanation for the bioactive compounds from C. zedoaria and P. niruri that keep the population of Th17 cells relatively high, nor its mechanism of action.

Cheral extract attenuate the TGF-β expressing CD4 + CD25 + regulatory T cells to a normal level

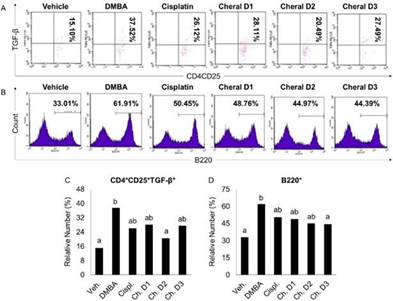

Various types of cells, including immune cells such as platelet cells, lymphocytes, and malignant cells, could release TGF-β. It is also predominantly expressed by activated regulatory T cells, which regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, and death (Sun et al., 2016). Treg cells are capable of secreting TGF-β, while TGF-β is vital for differentiating Treg cells, creating a positive feedback loop (Ashrafizadeh et al., 2020). The results demonstrated that the cancer control group’s relative number of TGF-β-expressing CD4+CD25+ T cells rose considerably as compared to the vehicle group (Figure 5A and 5C).

Note: derived from research.

Figure 5 The immunosuppressive effects of cheral extract toward CD4+CD25+TGF-β+ Treg cells (A and C) and B220+ B cells (B and D) in DMBA-induced mice. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. Different alphabetical characters on the graph indicate a substantial difference.

Cancer cells would exploit the Treg population, which has immunosuppressive capabilities by suppressing the activity of dendritic, CTL, and NK cells, leading to persistent immune infiltration and intensifying the development of breast cancer, therefore it is predicted that the relative proportion of Treg cells rose in the DMBA-induced group (Jean Baptiste et al., 2022, Ohue and Nishikawa, 2019, Togashi et al., 2019). Recirculating Tregs have a large number of IL2R (CD25), which is critical for their formation because it actively binds to IL-2, suppressing the immune response to malignant cells or the environment by reducing cytokine production, which also plays a role in tumor growth suppression (Chinen et al., 2016). A surge in TGF-β expression in cancer was associated with a comparatively large number of Treg cells. TGF-β- expressing regulatory T cells will maintain homeostasis by secreting inhibitory cytokines such as IL-35 and IL-10, which are critical in recruiting and fostering M2 cell development. TGF also stimulates the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cellsinto regulatory T cells, increasing the number of regulatory T cells proportional to the quantity of TGF-β-expressing CD4+CD25+T cells (Li et al., 2020).

In the breast cancer model, ROS concentration in the TME is raised due to persistent inflammation and oxidative stress induced by DMBA. This condition increases ROS and could drive further TGF-β expression via various signaling pathways, including the ROS-sensitive Smad2 pathway (Krstić et al., 2015). By dimerizing IKK, the ROS can directly affect the NF-κB activation pathway. The IKK complex can be activated because the IKK phosphatase molecule is particularly sensitive to ROS, hence, phosphorylation of IKK will result in NFκB activation (Zhang et al., 2016). Meanwhile, TGF-β promotes tumor formation by inhibiting transcription factors of pro-apoptotic enzymes on cytotoxic T cells, such as granzyme A and B, perforin, and Fas ligand. It is also thought to suppress APC activity, reducing the activation of CD4+, CD8+ T cells, and NK cells, and subsequently promotes anti-tumor activity (Karpisheh et al., 2022, Teymouri et al., 2018).

TGF-β-expression is increased in breast cancer patients, particularly in the later stages, because it promotes tumor growth by enhancing tumor invasiveness and metastasis (Boye, 2021, Syed, 2016). The relative number of Treg cells and their TGF-expression in cheral groups is considerably lower than in the DMBA-induced group, notably in the D3 group. Because TGF-β is an autocrine peptide produced by Treg cells that is also crucial for Treg development, reduced levels of TGF-β may result in fewer Tregs in both the TME and the circulatory system. Curcumin, one of the main constituent compounds of cheral, has been linked to various TGF-β signaling pathway suppressing activities, such as inhibiting Smad3 interaction with Smad4 and their nuclear translocation, downregulating the NF-κB pathway, and suppressing the doxorubicin-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) pathway, resulting in a lower chance of developing chemotherapy-resistant cancer cells (Ashrafizadeh et al., 2020, Yin et al., 2019). Corilangin in P. niruri may also stop TGF-β interaction from activating the AKT/ERK pathway, inhibiting cancer cell proliferation (Saahene et al., 2021). According to one study, quercetin, a significant bioactive component found in C. zedoaria and P. niruri, inhibits miR-21 to reduce TGF-induced fibrosis and activates the JNK pathway to cause death in KRAS-mutant colorectal cancer cells (Li et al., 2019). Those effects subsequently inhibit tumor growth and eliminate them, resulting in lower number of cancer cells, which also impacts the number of Tregs cells because of TGF-β autocrine characteristics. Meanwhile, curcumin suppression of IL-10 may impair CD4+ cell development towards Th17 phenotypes. It is also considered to down-regulate CTLA-4, a protein on their cell surface that interacts with CD80 molecules, resulting in signal transduction from Tregs, and FOXP3, which is critical for T cell development, inhibiting the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into Tregs cells (Bose et al., 2015, Paul and Sa, 2021). Curcumin may lower the number of TGF-II receptors and influence the Smad3 and Smad4 pathways, resulting in a considerable decrease in the relative amount of TGF-expression by Treg cells (Thacker & Karunagaran, 2015). However, this lower trend after administration of cheral on the Tregs number and TGF-β expressed does not seem to match the relative number of Th17 cells in the previous chapter because the cheral group’s number was insignificant to the DMBA-induced group, or even higher. Even though TGF-β is one of the main contributors to Th17 differentiation, it seems like there is higher influence from other cytokines that we did not measure in this study for the differentiation mechanism.

Cheral extract decrease the B220 + B cells population to a normal level

B220 antigens represent a subset of mouse CD45 isoforms predominantly expressed on all B lymphocyte lineages, including pro-, mature, and activated B cells (Yam-Puc et al., 2018). It is one of the main components of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer (Shen et al., 2018). The cancer control group had the highest relative number of B cells, while the cisplatin, D1 and D2 of cheral exhibited a significantly lower number of B cells (Figure 5B and 5D). Meanwhile, the group with the highest dose of cheral showed nearly identical results to the healthy control group, as seen by the lack of significant differences between those treatment groups. The increase of B cell population in cancer mouse models is caused by a higher concentration of B lymphocyte chemoattractants such as CXCL12 and CXCL13, increasing the recruitment of B cells to TME (Fridman et al., 2021, Gao et al., 2021, Nagarsheth et al., 2017). It is considered that a high amount of tumor-infiltrating B lymphocytes has two opposing effects. Its population is associated with a better prognosis in breast cancer because it increases T cell responses by releasing effector T cell recruiting cytokine, acting as APCs to CTLs in TME, and producing specific antibodies such as IgG and IgA targeting tumor antigens, which is an important factor in activating cytotoxic cells via antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (Fridman et al., 2021, Nagarsheth et al., 2017).

On the other hand, many B lymphocytes create antibodies that deposit in precancerous lesions, feeding chronic inflammation via Fc receptor (FcR) activation of innate cells moving into preneoplastic and neoplastic TME. Furthermore, B cells can limit T cell responses by producing immunosuppressive cytokines such as TGF-β and IL-10, which are both needed for Treg development and reducing effector T cell responses (Fridman et al., 2021, Sarvaria et al., 2017). However, we did not identify the subset of B cells in the samples in our investigation since all subsets exhibit B220 molecules on their surface. Based on the effects of M2, Th17, and Treg cells, it is postulated that B cells operate as anti-tumor rather than pro-tumor agents in this situation.

Meanwhile, there was a significant drop in B cells’ relative number in cancer patients following cisplatin chemotherapy. The drug’s effect targeting actively dividing cells may explain the decrease in the relative number of cells following cisplatin prescription. Immunocompetent cells actively proliferate in response to cancer progression, hence cisplatin reduces the relative number of B cells (Ziebart et al., 2017). The results demonstrated that Cheral treatment reduced the relative number of B cells in the spleen, which was affected by the high content of flavonoids and polyphenols, both of which have antioxidant properties. We suspect that the subset of B cells lowered by cheral administration is Breg cells. Flavonoids and polyphenols’ antioxidant activity reduces the quantity of ROS generated in breast cancer cells by acting as electron receptors, destabilizing the ROS, further lowering NF-κB activity, and leading to a lower number of B lymphocytes (Willenbacher et al., 2019). Curcumin and phyllantin have also been demonstrated to limit B cell proliferation, dropping the relative number of B cells (Jantan et al., 2019, Willenbacher et al., 2019). Curcumin can also inhibit BKS-2 and the expression of the c-myc and egr-1 genes (Giordano and Tommonaro, 2019). Based on this description, it is clear that cisplatin and Cheral can lower the relative number of B cells following their administration.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that dietary combined herbs extract of Curcuma zedoaria and Phyllanthus niruri exerts a dose-dependent immunosuppressive effect in a DMBA-induced breast cancer mouse model by modulating key immune cells, including M2 macrophages, Th17 cells, regulatory T cells, and B cells in the spleen. Flow cytometry confirmed altered immune profiles, and in silico analysis supported potential multi-target interactions with inflammatory and oncogenic proteins. This in vivo study evaluates the dose-dependent immunomodulatory effects of Cheral extract, highlighting its therapeutic potential in resource-limited settings. Further studies are warranted to validate active compounds, explore underlying molecular mechanisms, assess tumor volume and survival outcomes, and integrate transcriptomic or proteomic analyses for deeper mechanistic insights.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Brawijaya University for supporting and funding this study (M.R.).

Author contribution statement

All the authors declare that the final version of this paper was read and approved.

The total contribution percentage for the conceptualization, preparation, and correction of this paper was as follows: W.E.P., A.M.L.S.M., D.R., D.C., A.H., & M.R. 100%.