Introduction

Bilingual education provided through the Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) approach, its implementation, and the resulted multilingual future society is the ambitious project that the European Union (EU) has been promoting for the last 30 years (European Commission,1995). Paradoxically, the Spanish Education system, that allows a decentralized framework, has facilitated the implementation of this EU policy. Notwithstanding, the independency of the 17 Spanish autonomous communities, runs by their Regional Ministries of Education and, ultimately, the schools have formed a heterogeneous map of CLIL’s implementation around the country (Madrid Fernández et al., 2019).

This reality has caused changes throughout the 17 Communities in the understanding of CLIL implementation, putting the emphasis on the development of an array of regulations concerning content teaching and learning through CLIL, which have blurred an effective procedure of the teacher training in planning and delivery of lessons in the CLIL classroom (Custodio-Espinar & García Ramos, 2020a). To this lack of CLIL qualified teachers, Martín del Pozo (2015) adds that scientific research is placing the emphasis on the language proficiency of teachers, disregarding methodological issues.

Administrations are tackling this reality with the creation of training programs in bilingual education for in-service teachers to palliate it. However, its voluntary nature has resulted in the CLIL teacher paradox described by Custodio-Espinar and García Ramos (2020a), “teacher training for bilingual education is deficient, teacher training for CLIL is voluntary and the qualification / accreditation to provide CLIL in bilingual programs, generally, only considers the teacher’s linguistic competence” (pp. 11-12).

The Bilingual Program of the Community of Madrid (BPCM) began in 2004 in Primary Education. Currently, more than 50% of the schools in Madrid belong to the PBCM, and the program continues to grow (Comunidad de Madrid, 2021). These state schools teach at least 30% of the school hours in English, which means that, in addition to the First Foreign Language area (English), at least two more areas of the Primary Education curriculum, preferably Natural Sciences, are taught in English.

According to the latest map of the network of bilingual schools, the PBCM is now made up of 399 state primary schools, 190 secondary schools and 216 bilingual semi-private centers (Comunidad de Madrid, 2021). The number of schools implementing the BPCM in Infant Education has grown from the first 35 in 2017-2018, to 109 schools with a projection of 12.679 infants learning in English next school year (Comunidad de Madrid, 2021). At this stage, teaching in a foreign language (English) is focused on oral comprehension and expression and is approached through the contents of the different areas or fields of experience of this educational stage during the three, four and five weekly sessions of 45 minutes scheduled for the first, second and third year of the stage, respectively (Order 2126/2017).

With regard to Infant teachers’ access to CLIL programs, the model of accreditation in Spain consists almost exclusively of linguistic certifications. Certainly, there is a solid trend in the European Union misjudging CLIL (Martín del Pozo, 2015) and considering it as another language teaching methodology. Indeed, Eurydice (2017) states that the CLIL accreditation model to work in Infant CLIL contexts is neither homogeneous nor standardized. The named criteria tended to be based on linguistic proficiency and there are none or superficial governmental regulations (Pérez-Cañado, 2018a).

According to the Order 2126/2017, as their Primary counterparts, Infant Education teachers, who teach in English, must be in possession of the linguistic qualification for the performance of bilingual positions called habilitación lingüística, and receive a complement of productivity for special dedication. Therefore, no changes concerning CLIL pedagogical competence have been introduced and the CLIL teacher paradox described in Custodio-Espinar and García Ramos (2020a) is perpetuated.

Considering this scenario, the design of plausible training actions for in-service Infant teachers requires a deep-looking at CLIL contexts in this stage, which implies diligently researching Infant CLIL teachers, their competence regarding planning and delivery of CLIL lessons and experience about CLIL approach and, ultimately, the efficacy of training programs offered by the administrations in this regard.

Bearing in mind that CLIL requires novelty within its execution, teachers’ role is a niche that requires an in-depth adjustment (Pérez-Cañado, 2018a). CLIL teachers need to do an extra effort to move from old-fashion teaching styles to become guides and facilitators of the teaching-learning process, which, obviously, requires specific training. Moreover, CLIL has particular features that make it different from any other bilingual approach, hence, it needs curriculum changes and real collaboration amongst all CLIL teachers in order to develop an application of CLIL at the lesson planning level according to its theoretical foundations (Pérez-Cañado, 2018a).

Both the educational administration and the universities have to equip CLIL teachers with the innovative demands that CLIL asks them to exert (Garijo et al., 2018). However, educative administrations are mindful and recognize the lacuna in CLIL formation (Custodio-Espinar & García Ramos, 2020a; (Garijo et al., 2018). At the academic level, the situation is not better since not all student teachers have a CLIL-focused academic program, although they are all potential CLIL teachers (Gutiérrez Gamboa & Custodio-Espinar, 2021). Besides, there is a scarcity of preschool CLIL researchers, yet there are promising examples, such as García Esteban (2015) who gives some positive light showing that the function of CLIL with preschool students is effective and prompts all the components of the 4Cs described by Coyle et al. (2010).

According to Pérez-Cañado (2018b), to guarantee CLIL’s durability and attain homogeneity in its application, quality professional development to cultivate adequate CLIL teachers’ competence profile is a requisite, and also preparation in relation to professional identity (Morton, 2019). Madrid Fernández et al. (2019) note that the management in a CLIL realm is formed by the CLIL program coordinator, the content, foreign language, and language teacher, and the language assistant, who have to collaborate to make the best of their CLIL program. Therefore, teacher-team coordination is vital to plan and face the adversities of CLIL and develop the teaching competences necessary for sustainable CLIL provision (Pavón et al., 2020).

In addition, for an optimal implementation of CLIL, although, native speakers are not crucial, a proficiency level of the target language is desirable. However, it is not enough, because research has also shown that command in the methodology of bilingual education is one of the most important challenges to meet in all types of content-based instruction (Morton, 2019). Thus, there is a clear need for a compulsory battery of courses about methodological principles in CLIL (Custodio-Espinar, 2019a; Garijo et al., 2018; Morton, 2019; Pérez-Cañado, 2017, 2018b).

Concerning CLIL at Infant Education, Anderson et al. (2015) explains that “CLIL may often be understood as a more suitable approach for older children, already equipped with more advanced academic/ cognitive skills as well as perhaps some competence in the vehicular language” (p. 140). However, as Coyle et al. (2010) put it, “it is often hard to distinguish CLIL from standard forms of good practice in early language learning” (p. 17).

Preschool CLIL lessons have their own peculiarities. Firstly, CLIL promotes self-regulation of the learning process (Freihofner, 2018), which is connected to long-term academic achievement (Breslau et al., 2009; McClelland et al., 2014, cited in Anderson et al., 2015). This means that it is paramount to train Infant Education teachers to plan for CLIL lessons focused on self-regulation skills to improve misbehavior, emotion regulation, attention, impulsivity, self-directness and strategic learning in the classroom (Anderson et al., 2015, p. 141). Secondly, regarding the production of CLIL learning material, Almodóvar Antequera and Gómez Parra (2017) describe the following aspects to be considered by Infant Education teachers: visible objectives to children, promotion of standard language, development of learning skills and autonomy, variety of evaluation forms, cognitive inclusion, critical thinking, cognitive scaffolding and meaningful learning (pp. 83-85).

Besides, Riera Toló (2009) and García Esteban (2015) emphasize the need of organizing preschool contents from a global, comprehensive, and interdisciplinary perspective to develop CLIL lessons. In this sense, teaching the curriculum through specific topics or cross-curricular contents seems to be the most practical approach for teachers who need to develop lesson plans in bilingual education environments at this stage (García Esteban, 2015). This type of CLIL is known as soft CLIL, as opposed to hard CLIL or immersion programs where whole subjects are taught in the foreign language (Bentley, 2010). According to García Esteban (2015), it represents a practical training need in CLIL at Infant Education.

Such a demanding and complex teaching and learning scenario needs to be evaluated to guarantee the quality of the education provided. However, teachers tend to be skeptical towards external evaluation of their context since they may consider that it is used to control and influence them (Fuentes Medina & Herrero Sánchez, 1999). Conversely, according to the same authors, self-evaluation improves the pedagogical behavior, has the highest level of implication and participation from the stakeholders, and develops critical thinking boosting professional development. In the same line, Ross and Bruce (2007) outline that self-assessment is a powerful technique that can promote change in teachers and impact their professional growth and practice by influencing the teachers’ definition of excellence, helping select improvement goals, facilitating communication with the teachers’ peers, and increasing the influence of external change agents on teacher practice (p. 146). This way, teachers can develop their own training itinerary based on “clear standards of teaching, opportunities to find gaps between desired and actual practices, and a menu of options for action” (Ross & Bruce, 2007, p. 146) provided by the self-assessment tool.

Finally, effective planning of teaching practice is one of the key factors that can improve the CLIL learning process (Pérez-Cañado, 2017), therefore, identifying own strengths and weaknesses of the teaching process is essential to develop an effective CLIL training plan. Pavié (2011) also notes that the reflexive component is correlated with the professional actions with which preschool CLIL teachers can put into motion the machinery located in their own conclusions after a thorough self-reflection.

Thus, in order to provide the Infant teachers with a model of the ideal CLIL practice, the self-assessment checklist was designed based on the “Cuestionario de Integración de Principios Metodológicos AICLE” (CIPMA) (Questionnaire of Integration of CLIL Methodological Principles) (Custodio-Espinar & García Ramos, 2020b), which is a valid and reliable instrument to measure CLIL teacher competence to plan CLIL lessons. The questionnaire consists of four dimensions including 23 study variables grouped in Dimension 1 Core CLIL principles, Dimension 2 Methodology, Dimension 3 Resources and Dimension 4 Evaluation.

The main aim of this work is to explore and describe the strengths and weaknesses of using this self-evaluation checklist as a first step in CLIL teacher training in order to move the focus from the administration and institutions, which provide the courses, to the teachers themselves, who are responsible for choosing and participating in those courses. Other objectives are:

To build a bridge between research findings on CLIL teacher training and Infant teachers’ actual training needs and training actions on CLIL.

To boost in-service CLIL Infant teacher training initiatives likely to overcome the inhibiting factors for professional development.

To give evidence of the thoughts and practice of CLIL teachers in their bilingual classrooms at the Infant stage.

To demonstrate the utility of a checklist as a self-evaluation tool for CLIL Infant teachers to assess their competencies to plan CLIL lessons.

To offer an effective tool to motivate and foster CLIL Infant teachers’ desire to participate in training courses for CLIL.

Materials and methods

Qualitative case study is usually focused on experiential knowledge which is closely related to the social and political influences of a real-life context (Stake, 2005). Thus, this exploratory qualitative research, focused on the case study of one teacher, is chosen to provide deeper understanding of the CLIL teacher at Infant Education stage due to the current restricted access to direct field observations at schools because of the virus responsible for the COVID-19.

The target group of this proposal is Infant Education teachers who have to teach CLIL to 3-to-5-year-old students. An exploratory case study of one voluntary CLIL teacher in her infant education classrooms was developed to check the viability of the proposal. The participant is a 40-year-old Spanish teacher who teaches CLIL only at Infant Education stage in a state school in Madrid that belongs to the BPCM. She holds the specialization in Primary Education, Infant Education and Foreign Language and obtained the endorsement to teach in the BPCM in 2013. She has a C1 level according to the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) and has participated in the Plan de Formación en Lengua Extranjera (PFLE) in training courses for CLIL. Of her 16 years teaching experience, seven have been in the PBCM, of which three were in Primary Education and four in Infant Education. The levels observed were year 4 and 5 (4-5 and 5-6- year-old students).

The study uses participant-observer and linguistic data collecting techniques. Several instruments have been used including the checklist for the observer and for the teacher described. Also an observation protocol, transcripts of the interviews, a written feedback worksheet, and transcripts of the social networking site WhatsApp and the institutional email account were used to exchange information. The self-assessment checklist used (Custodio-Espinar, 2019b, pp. 28) is based on the dimensions and variable-items of the CIPMA and adapted to be used by the teacher and the expert observer (Appendices A, B). Therefore, it consists of four dimensions that cover the methodological principles for effective CLIL lesson planning: D1 Core CLIL principles, D2 Methodology, D3 Resources, and D4 Evaluation. The descriptors are measured using a Likert-type scale 1-4 for frequency.

To ensure that the interpretation of the data is reliable and valid, a triangulation of the teacher perceptions, researcher observations, and previous scientific research findings in CLIL Primary teachers with CIPMA was carried out. Stake (2005) defines triangulation as “a process of using multiple perceptions to clarify meaning, verifying the repeatability of an observation or interpretation” (p. 454). Thus, systematic comparison of the data collected from these stakeholders can help to clarify their meaning and verify the repeatability of the observation based on the use of the checklist presented (Stake, 2005).

Discussion of the results

The results of the innovation allow to state that self-assessment can promote and guide the necessary training in teachers’ competence to plan and deliver preschool CLIL lessons. As Pavié (2011) proposes, the development of self-evaluation strategies can help to overcome routinization, standardization of school management projects, and the lack of CLIL teachers’ autonomy and creativity. Clear evidence of this is summarized in this quote:

I forward you the checklist. Upon completing it I have realized how little I know or analyze my daily behavior in the classroom, I should give it a twist. I don’t really know the elements of a CLIL lesson plan for Infant Education (CLIL Infant teacher, personal communication, November 25, 2020).

Table 1 shows the result of the comparison between the teacher and the researcher scores.

TABLE 1 Comparison of scores by the Infant teacher and the observer in the checklist dimensions

| Stakeholder | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | Total |

| Infant teacher | 10 | 10 | 12 | 4 | 36 |

| Observer | 10 | 12 | 12 | 5 | 39 |

| Total possible score | 20 | 16 | 16 | 12 | 64 |

Source: Own elaboration.

Once the scores were calculated, the order of training priority was D4, D1, D2, and D3, which coincided in both checklists (teacher-observer). From the comparison the following results arise:

The scoring of the observer and the teacher on the areas of CLIL programming that require improvement, therefore, training, almost totally coincide.

The priority of the observer and the teacher on the areas of CLIL programming that require improvement, therefore, training, totally coincide.

The teacher’s training in CLIL and her competence to program CLIL lessons evaluated by the teacher’s and the researcher’s checklist are not coherent since she has received training in CLIL, but both in her self-evaluation and in the observer’s evaluation, there is space for improvement in the fundamental elements of the CLIL approach. The lack of recycling in her CLIL training explains the need to strengthen the core elements of CLIL (D1).

To be aware of these results, it is paramount to build a bridge between research findings on CLIL teacher training and Infant teachers’ actual training needs and training actions on CLIL. As Murillo et al. (2017) put it, at present, there is a culture in schools of rejection of research, but there is also a rejection on the part of teachers towards new knowledge that comes from outside the school (p. 197). Besides, Perines (2018) points out that student teachers lack training in scientific research, which is one of the elements related to the so-called crisis of educational research.

As afore stated, the self-evaluation strategy and peer or expert observation (Aguilar et al., 2020) can help CLIL Infant teachers to overcome the gap between educational research and teaching practice and turn their professional development into a self-reflection to understand and dig in an elaborated dialogue within the epistemology of CLIL (Pérez-Cañado, 2018a, 2018b). Besides, it can boost collaboration and participation in training initiatives likely to overcome the inhibiting factors for professional development that in-service teachers usually report (Custodio-Espinar, 2019a, 2019b). “I think that teachers are in great need of external evaluation and self-evaluation because it is the only way to improve. Peer or expert observation” (CLIL Infant teacher, personal communication, November 25, 2020).

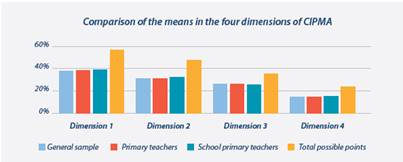

Custodio-Espinar and García Ramos (2020a) researched with the CIPMA a sample of CLIL teachers at Primary and Secondary Education, in the Community of Madrid. The means of the preschool teacher’s self-assessment (Table 1) were compared with the means of that sample (N=383), the means of the Primary teachers in that sample (N=272), and the means of the Primary teachers at her school in that sample (N=11) (Figure 1).

As can be observed, the means of her counterparts at school were similar to the other groups or above the average means in the four dimensions. In D4, the means were low in all cases, which is in line with the result of the checklist. Regarding to D1, it can be noted that the mean of the primary colleagues is slightly higher than the other groups. However, the result of the self-assessment in this dimension was the second lower. This can be due to the idiosyncrasy of the 4Cs when they are implemented in the Infant Education classroom and the previous experience of the teacher in both Primary and Infant CLIL which is likely to help her be aware of them and show a critical perception.

These results have also been evidenced by the thoughts and practice of the Infant CLIL teacher. The lack of adequate training for CLIL, the importance of the pedagogical competence and the competence to plan CLIL lessons have been manifested in her answers:

My training is fine for CLIL because my specialty is for Pre-primary and I transfer my knowledge of the methodology of this stage to the foreign language but not the general one, because they do not know the methodology of the stage in depth and work too much focused on the language but in a non-meaningful way, lists ... (CLIL Infant teacher, personal communication, November 25, 2020).

According to the teacher, CLIL teacher competence to plan lessons is important “…because the stage has an idiosyncrasy that makes it essential that in order to respect it, people know how to select content, tasks, etc. appropriate to these characteristics” (CLIL Infant teacher, personal communication, November 25, 2020). And the proficiency in the L2 is not enough, “…CLIL training is essential” (CLIL Infant teacher, personal communication, November 25, 2020).

From the linguistic point of view, according to the Infant teacher, she observed that she speaks in L2 50-60% of the class time with four-year-old students and 70-80% with five-year-old students. She noted that she uses the L1 little, and about her proficiency in the L2, she explained that “the language I work with is simple and does not help me improve, you lose linguistic competence in the long term” (CLIL Infant teacher, personal communication, November 25, 2020). Concerning her students proficiency, she placed them below or near the A1, and she considered that they use L2 10-20% as an average, although some are able to do it for 30-40% of the class time.

Finally, the qualitative feedback provided by the observer conforms to these results and reinforces the hypothesis that a self-evaluation checklist can be a particularly useful tool to assess CLIL teacher competence in lesson planning and delivery. Table 2 shows this feedback distributed in strengths and weaknesses observed in the two CLIL Infant classrooms.

TABLE 2 Qualitative feedback from the observation

| CLIL Infant teacher strengths | CLIL Infant teacher weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Excellent proficiency in L2 and a good role model for students. | The lessons work on content from a linguistic point of view rather than cognitive. |

| L2 is used with students even outside the classroom. | Tasks are presented at LOTS. More cognitively demanding tasks could be implemented. |

| L1 was only used to ensure understanding of tasks and to handle disruptive behaviors. Controlled use of code-switching. | The provision of transformation and production scaffolding can improve the quality of the interaction in the L2. |

| Learner-centered activities that favored personalization. | The lesson planning lacks formative assessment and the implementation of formative assessment |

| Group activities in the assembly or in pairs, collaboratively, which favored attention to diversity in the CLIL classroom. | tools such as checklists or rubric to assess students´ performances (D4). |

| Positive and dynamic classroom environment. Stressless use of the L2. | |

| Uninhibited students affectively linked to the teacher. The degree of receptivity to L2 was remarkably high, and the percentage of use of L2 of students was 40-50%. |

Source: Own elaboration.

From the analysis of the feedback provided (Figure 2), it is evidenced that the use of the checklist as a self-evaluation tool helped the teacher to realize aspects of the rationale of her CLIL lessons such as the CLIL approach she is implementing, soft CLIL (Bentley, 2010). “I integrate the topic of the project that they work with their tutor and work on the vocabulary of the project or topics” (CLIL Infant teacher, personal communication, November 25, 2020). She was also able to recognize her strengths with the CLIL pupils, such as “play, motivation, desire to go to the English classroom and to speak English, development of an attachment figure in English, interaction in L2, the affective and emotional” (CLIL Infant teacher, personal communication, November 25, 2020).

Teachers must put the focus on promoting infants’ self-regulatory apparatus (Anderson et al., 2015) by self-regulated learning strategies and techniques as the ones demonstrated by the teacher in this work (Figure 2). In this sense, Almodóvar Antequera and Gómez Parra (2017) claim for the search of a balance between the child’s own initiative and the most rigorous and predesigned work included in the lesson planning, in particular, in a school context regulated by an official curriculum such as the Spanish.

On the other hand, she remarked the following weaknesses: “In CLIL core elements, why I do what I do, the reflection of why I do this or that. Also, linguistic competence, language is limited in the classroom and recycling is required” (CLIL Infant teacher, personal communication, November 25, 2020).

The feedback and resources provided after the observation and analysis were very appreciated by the teacher. “Thanks for the ideas of the rubric, it makes sense to me” (CLIL Infant teacher, personal communication, December 2, 2020). As Aguilar et al. (2020) remark, teachers can directly incorporate the advice and recommendations offered by the observer into their teaching practice.

Synthesis and final reflextions

Promoting Infant Education teachers’ participation in CLIL training courses is paramount to ensure bilingual education quality at this stage. In this sense, this work has proven to effectively move the focus from the administration and institutions, which provide the courses, to the teachers themselves, by making them responsible for identifying their training needs using a self-evaluation checklist that unveils the strengths and weaknesses of their competence to plan CLIL lessons (Objectives 1, 2, 3). The direct observation and feedback provided on the spot have been taken into consideration by the teacher and the awareness of the need for development to improve CLIL teacher competencies has arisen (Objectives 1, 2). The agreement on the comparison of the results of the teacher’s self-assessment checklist and the observer’s checklist demonstrates the utility of a checklist as a self-evaluation tool for CLIL Infant teachers to assess their competence to plan CLIL lessons (Objective 4). In order to achieve objective 5, a checklist to evaluate the implementation of the self-assessment strategy to uncover CLIL training needs at Infant Education schools is included (Appendix C).

Finally, this study may encourage CLIL teachers to self-assess their practices in the CLIL classroom through the use of different tools such as the checklist presented in this article or other research instruments and methods such as lesson study (Crehan, 2016) or “(auto) ethnography to put forward detailed and honest descriptions of challenges, successes, and failures in CLIL” (Banegas & Del Pozo Beamud, 2020, p. 11).

In future studies, a multi-case approach including the combination of the study of individual CLIL teachers, and their Bilingual Schools and Bilingual Programs can shed some more light on the complex phenomenon of in-service CLIL teacher training. Besides, as part of existing programs, the use of the self-evaluation checklist can orientate and help teachers to make the best of them. The proposal can also be used by CLIL teacher educators in Infant Education degrees as a role model of good practice, both from the methodological point of view and, more important, from the point of view of lifelong learning strategies for professional development so necessary when teaching in CLIL classrooms. To conclude, self-evaluation is not the golden strategy to solve all the constrains in CLIL implementation, but it may well serve as a starting point igniting the adequate machinery to exert appropriate CLIL training actions for Infant Education.

Ver apéndices A, B y C en formato pdf.