1. Introduction

COVID-19 is an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which affects people in different ways, with or without mild symptoms, and can lead to death (World Health Organization (WHO), 2021). The aforementioned disease has, since 2020, affected the world in alarming proportions, being identified as the biggest global health crisis since the second world war, and configured as a pandemic (Mishra et al., 2020).

In order to reduce the spread of COVID-19, the WHO recommended the intensification of hygiene habits, as well as the restriction of contact between people (WHO, 2021), measures widely adopted by most countries. Above all, social isolation has generated several changes at a global level, which are still reverberating in different social spheres (Kaup et al., 2020; Mishra et al., 2020).

In the area of education, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) points out that the COVID-19 pandemic has affected 70% of the world's student population, impacting more than 52 million students in Brazil alone (Unesco, 2021). According to Vilchez et al. (2021) and Coulter et al. (2021), as schools are closed environments, which keep many people confined for long periods, they were one of the first institutions affected by these determinations.

One year after the beginning of the pandemic, with more than half of the world's students affected by the partial or complete closure of schools, UNESCO warned of the need to think about an educational recovery, in order to avoid a generational crisis in education (Unesco, 2021). Therefore, considering alternatives that minimize the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic presented a challenge to countries, which, in this effort, evaluated the remote class format as a possibility (Elisondo, 2021; Filiz and Konukman, 2020).

This conjuncture establishes what has been referred to as Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT), which, in practice, is the exceptional transposition of pedagogical practices and face-to-face educational agendas to the online format, mainly using digital platforms (Castaman et al., 2020; Hodges et al., 2020; Joye et al. 2020). ERT represents a challenge, especially for practical subjects, in which interaction and socialization are normally encouraged, such as Physical Education classes (PE). In addition, other investigations point to the educational inequalities that can be expanded due to the restricted access to technology experienced by some portions of the population (Chaverri, 2021; Elisondo, 2021).

Given this scenario, understanding the experiences of PE teachers during the pandemic will help to provide a broader understanding of this context, generating reflections that can contribute to overcoming past challenges and those that are yet to come. Howley (2021), in his study carried out in different parts of the world, points out that the transition to remote teaching has been challenging for teachers. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to investigate the Perceptions of Physical Education teachers from a metropolitan region of southern Brazil about the repercussions of the pandemic on their pedagogical practices. In order for the main objective to be achieved, we sought to answer the following questions: How was the initial adaptation process of teachers in relation to the pandemic? What were the difficulties and facilities found by teachers during their pedagogical practices in emergency remote teaching? How was the process of returning teachers' practices to face-to-face teaching?

Therefore, we organize this text with this introduction, followed by a contextual background presented in the theoretical framework: Repercussions of COVID-19 for world education. In the following topic, methodology, we present the investigative path used, then we present the results together with the discussions and, finally, the final considerations.

2. Theoretical Reference

2.1 Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in the world

COVID-19, a disease that began to spread between late 2019 and early 2020, surprised the world population by spreading alarmingly (Joye et al. 2020; Kaup et al., 2020; Mishra et al., 2020). According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), less than a year after the spread of the disease, in November 2020, the number of people infected totaled more than 57.8 million cases, in addition to 1.3 million deaths worldwide (WHO, 2021). A year later, at the end of 2021, there were more than 500 million cases and 6 million deaths worldwide (WHO, 2021). In Brazil alone, at the beginning of 2022, deaths from the disease totaled more than 650 thousand people. Thus, we highlight that so far Brazil is the third country most affected by the disease in the world and the first in Latin America (United Nations, 2021).

Due to the alarming scenario of contamination and deaths, at the beginning of 2020, the WHO announced some necessary measures to preserve life, minimizing contamination, mainly from social isolation and the intensification of cleaning and hygiene habits, bringing many changes in all spheres of life for the world's population (Kaup et al., 2020; Mishra et al., 2020; Stodolska, 2020). Thus, we had no choice but to rethink the limits of our time at home, on the street, at leisure, and at work (Liu et al., 2021; Stodolska, 2020). Thus, the world population has undergone a long period of drastic changes in social habits and life organization, accompanied by feelings of fear and insecurity caused by the global health crisis.

According to Carvalho et al. (2020), the emergence or worsening of anxiety, stress, and depression are some of the psychological effects that the pandemic and its implications can generate in people. Other studies corroborate this information (Faro et al., 2020; Schmidt et al., 2020), emphasizing that the pandemic developed concerns that can lead people to psychological suffering, resulting in problems such as anxiety and depression. Therefore, the context of the pandemic needs to be understood and studied in a way that is sensitive to these particularities, as we all suffer in some way from this situation faced by humanity, directly impacting our physical and mental well-being.

2.2 Impact of COVID-19 on education

For Filiz and Konukman (2020), on the educational challenges that present themselves in the pandemic, schools in Europe and the United States quickly organized themselves to continue learning through distance learning tools with ERT. A similar movement is presented in Elisondo (2021) investigation of teachers from Argentina, in the context of South America. This way, in Brazil, in 2020, the Ministry of Education decreed the replacement of face-to-face classes with classes in digital media.

In the particularity of Santa Catarina, a Brazilian state that includes the city where this research was carried out, after nine months of remote teaching, the government established general conditions for the resumption of face-to-face activities in the area of Education, in public and private education networks (Portaria N° 343, 2020). Each school was required to define their own return strategies and the form of face-to-face service, considering all the standards of health measures and social distancing, with a view to returning on the first school day of 2021.

Respecting the rules established by the state, the return to face-to-face teaching did not occur completely and suddenly, facing several challenges. Schools with insufficient physical space to respect social distancing were required to organize strategies alternating between groups, maintaining both face-to-face and remote activities, constituting a kind of hybrid education. In addition, the student's legal guardian was able to choose to continue the regime of non-face-to-face activities.

In practice, authors like Pressley and Ha (2021) report, in different parts of the world, the different routes for returning to face-to-face activities led teachers to work in three teaching modalities (sometimes simultaneously): remote teaching, face-to-face teaching, and hybrid teaching (mix of the two formats). In Santa Catarina, as a condition for the return of face-to-face classes, the PE discipline, in addition to general cleaning and hygiene protocols, was required to be carried out outdoors, maintaining a distance of one and a half meters between students, as well as prohibition of the practice of sports involving surfaces and objects that cannot be sanitized.

2.2.1 Impacts of the pandemic on physical education classes

Initially, it is worth noting that in Brazil, PE is a mandatory curricular component in schools, even if at certain times this subject is interiorized in relation to others within the educational context, this aspect reinforces the importance of this subject for society. Mercier et al. (2021) point out that the pandemic experienced excessively isolated physical education teachers already in a stigmatized area, making the planning and implementation of PE classes fall on PE teachers themselves.

It is possible to say that the discipline of Physical Education was one of the most needed to undergo changes, given that it has significant practical content. In addition, the lack of physical presence of the PE teacher makes it difficult to guide students so that they are within healthy patterns of physical activity, as well as doing so in a pleasant way (Mercier et al., 2021). Nonetheless, American studies such as the one by Mercier et al. (2021) point out that face-to-face teaching of PE classes also can be a favorable context to promote effective results in student learning. This highlights the challenges of ERT in the PE discipline.

The challenges experienced during adaptations and challenges facing the necessary emergency remote teaching could be perceived in a positive and negative way by physical education teachers investigated in the studies by Centeio et. al (2021), highlighting the overcoming and technological learning, the involvement of students in the teaching-learning process and the creation of good pedagogical content. Furthermore, in the case of barriers, the teachers perceived, mainly, difficulties in meeting the specific needs of each student.

For this reason, Mercier et al. (2021) seek that, although strategies for remote physical education classes change with the institution where teachers work, it is important that teachers work for alternatives that meet the needs of students.

3. Method

3.1 Approach

This is a descriptive and exploratory field research, with a qualitative approach to the data (Gil, 2010; Minayo, 2012). Exploratory studies, according to Gil (2010), aim at greater familiarization with the problem, considering the different aspects inherent to the phenomenon studied. In turn, descriptive research has the purpose of describing in detail the characteristics of the investigated elements and, if possible, verifying the possible existing relationships, being able to have the intention to raise opinions, attitudes, or beliefs of a certain group.

This study is still classified with a qualitative approach since qualitative research cannot be quantified, that is, this type of investigation is related to the universe of meanings, motives, attitudes, and values (Minayo, 2012).

3.2 Procedures and participants

This study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee with Human Beings (CEPSH) of the University of the State of Santa Catarina (UDESC), under opinion No. 2,950,528, on June 30, 2020. Thus, following the precepts ethics of Resolution 510/16 of the National Health Council on research with human beings.

As an inclusion criteria, PE teachers needed to work in basic education institutions, whether public or private, as well as they should have taught their classes during the period of social isolation caused by COVID-19. These PE teachers teach in the metropolitan region of Florianópolis, located in the state of Santa Catarina (Southern Brazil), which comprises nine cities.

To identify the participants in this research, the intentional sampling technique proposed by Vinuto (2014), denominated “snowball” was used. In this way, some people who met the requirements to participate in the research were located, denominated “seeds”. Subsequently, the seeds were asked to indicate new contacts with the desired profile, and so on, until there were no new names to participate in the research (Vinuto, 2014).

Those who voluntarily agreed to participate in the study signed a Free and Informed Consent Form and a Consent Form for online Photographs, Videos, and Recordings. To preserve their identities, participants were able to choose fictitious names to be identified in this study. Therefore, 16 PE teachers from public (9) and private (7) educational institutions participated in this study.

These teachers, chosen in a non-random manner, worked with different teaching modalities during the pandemic: face-to-face teaching (FFT), emergency remote teaching (ERT), hybrid teaching (HT); and different stages of basic education. Some teachers work simultaneously with more than one teaching modality. In addition, this information represents the situation of teachers at the time when they participated in the research. The characteristics are described in more detail in Table 1.

Table 1 Characteristics of the participating teachers of Santa Catarina, Brazil, 2021.

| Fictitious name | Modalities of teaching provided at the moment | Age (years) | Sex | Type of institution |

| Ana | FFT; HT | 22 | Female | Public |

| Andrei | FFT | 49 | Male | Public |

| Antônio | FFT / HT | 28 | Male | Private |

| Bianca | FFT | 28 | Female | Private |

| Felipe | HT | 25 | Male | Public |

| Girassol | HT | 45 | Female | Private |

| Lau | FFT | 21 | Female | Private |

| Lilica | HT | 36 | Male | Public |

| Maria | FFT / ERT / HT | 32 | Female | Public |

| Patricia | HT | 29 | Female | Public |

| Pedro | FFT | 22 | Male | Private |

| Lari | HT | 24 | Female | Public |

| Roberto | FFT | 43 | Male | Private |

| Sara | HT | 25 | Female | Private |

| Saraiva | HT | 34 | Male | Public |

| Sol | FFT/ERT/HT | 30 | Female | Public |

Source: Authors, 2022.

1/ FFT -Face-to-face teaching; HT - Hybrid teaching; ERT - Emergency remote teaching.

3.3 Data collection

The instrument used for data collection was the semi-structured interviews which were conducted online during the months of June and July 2021. According to Minayo (2012), semi-structured interviews can combine closed and open questions, where the person interviewed can talk about the questions without getting stuck on them, thus, it can be considered more flexible.

The semi-structured script was reviewed by three Ph.D. researchers, in order to understand teachers' perceptions of their pedagogical practices during the pandemic. The interviews took place through the Google Meet videoconferencing platform, where the PE teachers were able to speak freely about the questions asked, which mainly addressed aspects related to the way the classes are being taught, the main difficulties and facilities at this moment, and how the teachers perceive the students during the return to face-to-face teaching.

The 16 interviews, which together total about 20 hours, were transcribed in their entirety in about 60 hours (112 pages). The choice to carry out the interviews in the online format was due to the impossibility of carrying them out in person, given the health measures that were established as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, in addition to greater safety for participants and researchers in the current situation, Schmidt et al. (2020) highlight the strengths of online interviews as the time reduction in data collection. Even before the pandemic, conducting online interviews was widely explored in the literature (O'Connor and Madge, 2017; Salmons, 2012), especially in the execution of social research.

To ensure the consistency of the information obtained, ensure the reliability of the study, according to Polit and Beck (2014), the following actions were established: the instrument was reviewed by three Ph.D. researchers familiar with this research instrument; the interviews were carried out and transcribed by the main researcher of the study; finally, the data were analyzed, checked, and discussed by the study researchers.

3.4 Data analysis

The interviews were transcribed in their entirety, by the main researcher, which took approximately 60 hours. Data were organized using NVivo-12 software and analyzed using the content analysis technique proposed by Bardin (2009). This technique is subdivided into three chronological phases: pre-analysis; material exploration; and treatment, inference, and interpretation of data.

The pre-analysis phase aims to organize and systematize the initial ideas, through fluctuating reading of the information obtained, choice of documents, formulation of hypotheses and objectives, and development of indicators. The material exploration phase is the moment of coding, decomposition, or enumeration of the items obtained during the pre-analysis, to identify the recording and context units. In the final stage, the categories of analysis appear, which are compared with the literature (Bardin, 2009).

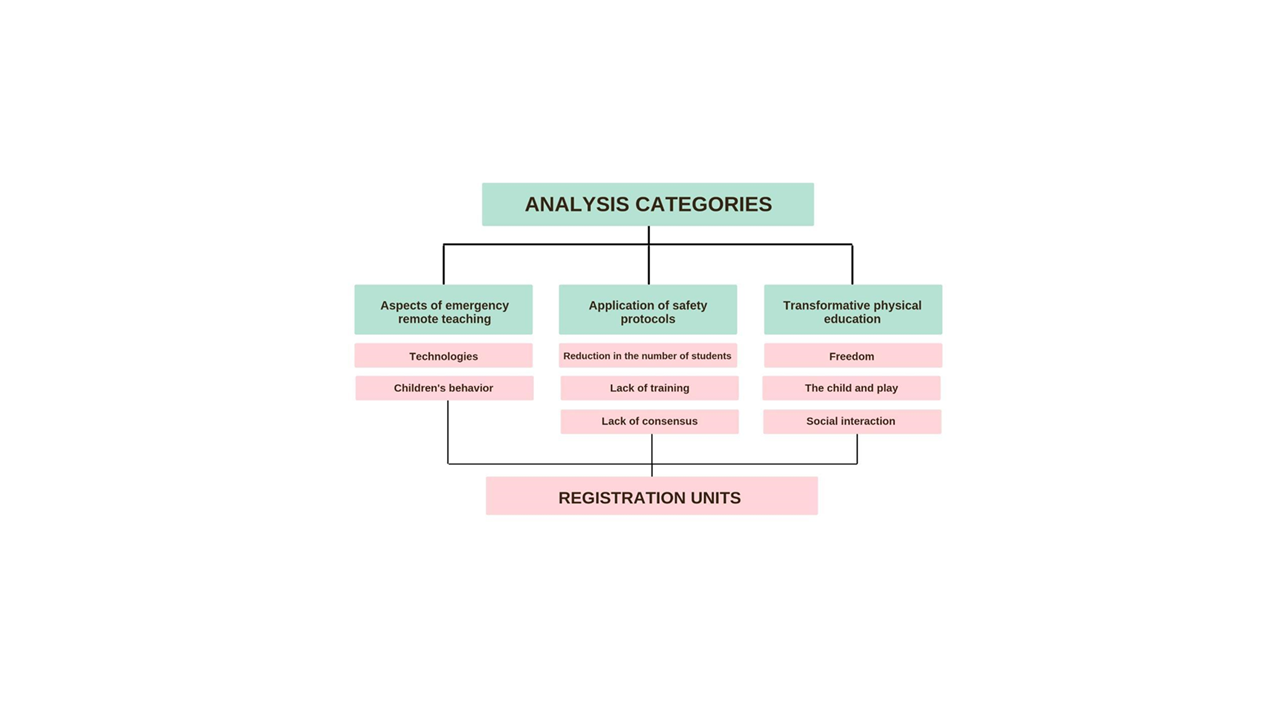

The analysis categories found, as well as their respective context units, are shown in Figure 1.

4. Results and Discussion

The results will be presented and discussed in the categories of analysis: Aspects of emergency remote teaching; Application of safety protocols; and transformative Physical Education. The first category presents significant records elements that involve technologies, in the contexts: pedagogical instrument and influence on the child. In turn, in “Application of safety protocols”, questions are highlighted about the support that teachers received (or not) to develop their pedagogical activities in an unstable context. Finally, “Transformative Physical Education” addresses the potential of the PE discipline in terms of overcoming difficulties presented by the current situation.

4.1 Aspects of emergency remote teaching

The abrupt insertion of the technological and digital universe in schools reverberated in different facilities and difficulties perceived by PE teachers, which were mentioned in relation to their pedagogical practices during the COVID-19 pandemic, and student behavior in the classroom.

For the investigated teachers, among the main positive points of the experience with ERT for their pedagogical practice is the acquisition of knowledge about different technological instruments that can be used in their classes, expanding the possibilities of pedagogical performance. Girassol (private school) mentions: “we have evolved a lot in relation to technology, we are using the tools in our favor. All this has been added and will not go away”.

This shows that, during ERT, technological resources can be used as a strategy to stimulate student interest. Jeong and So (2020) describe that remote classes are inefficient if students do not participate actively and responsibly. The authors state that the attitudes and interest of students in relation to this type of teaching, which has become practically self-directed, is an important factor in developing remote PE classes.

Therefore, when using technological resources as a teaching strategy, not only is the participation of students stimulated, but their knowledge is valued. The student is able to share knowledge and develop collaborative work, facilitating their participation in the teaching and learning processes. In this same sense, Lau affirms:

I believe that after these two years of the pandemic, we are leaving with much more knowledge about technology, with more background to give interactive classes and take advantage of this internet medium. We know that children nowadays understand much more than we do and luckily we ended up improving ourselves in this regard. (Lau, private school)

For Hodges et al. (2020), ERT is making teachers rethink their practices to use these experiences in the future. Likewise, Elisondo (2021) identifies in his investigation in the Argentine context, that significant learning is related to the appropriation of technological resources, contributing to the acquisition of relevant competencies to solve complex problems of the teachers. Wahl-Alexander and McMurray (2021), from Northern Illinois University, emphasize that the teacher can use technologies for gamification of PE classes, being a resource that brings motivation and student engagement, being a positive element in learning.

For this, Moreira et al. (2020) state that training programs should be created for all educational agents, helping them to include technological means in their pedagogical practices. In addition, teachers perceive the use of technologies in their pedagogical practice as an advance in traditional education and a way of approaching students through this means so common to them, as exemplified by Lilica:

The positive point is related to the possibilities that technology brings us to work on a daily basis with children. I produced a game where they had to move according to the screen guidance. It was cool because this is their reality, and it's something we didn't use to take to classes before the pandemic. (Lilica, public school)

In this regard, Centeio et al. (2021) claim that forms of remote instruction in PE are likely to be present even after the pandemic, as this may contribute to learning experiences in the future. On the other hand, what for some teachers was presented as a possibility, for others was a difficulty. The same is pointed out by Jeong and So (2020) in a study carried out in Korea, when the authors reported that the sudden adoption of remote teaching left teachers struggling with teaching methods, which they were not used to, forcing them to use trial and error teaching methods. Equally, Elisondo (2021) identifies different difficulties experienced by Argentine teachers as a result of the ERT. In this regard, Maria exemplifies:

For me, being able to adapt PE content to this medium was a great difficulty. Before the pandemic, I already suffered from some understanding limitations regarding these technological issues, and during the pandemic, this was even more evident from the point of view of technical knowledge, and to this day this is a problem for me. (Mary, public school).

Moreira et al. (2020) mention that alterations in school routine require the teacher to rethink their practice, forcing them to assume roles and communicate in ways they are not used to. In addition, if prior to the pandemic teachers already had difficulties in using technological resources to aid their pedagogical practices, after the beginning of the pandemic, with all the uncertainties, concerns, and fears that came linked to it, the difficulties in working in this environment became even greater. Howley (2021), in a study composed of 10 PE teachers from various locations around the world, all participants reported that the sudden transition from face-to-face to online classes was scary and they were not prepared to take on this new teaching methodology.

The different perceptions of teachers about the use of technological tools in their classes allow us to affirm that, although the absence of specific training for the use of technologies, as a pedagogical instrument, can be a difficulty, it does not preclude good pedagogical experiences, nor does it make the discipline less effective in terms of its objectives, as reported by the investigated teachers. Although, it is important to mention that recognizing the potential of the use of technologies in teaching does not imply ignoring that, unfortunately, such opportunities do not reach all contexts equally (Chaverri, 2021).

The aforementioned aspects were also identified in the study by Mercier et al. (2021) with teachers from the United States where, when carrying out a self-assessment, most teachers reported that while the lack of preparation - due to the rapidity of the transition to a remote learning environment - was a hindrance, it did not make the remote teaching less effective. That said, we agree with Centeio et al. (2021) and Mercier et al. (2021), who emphasized the importance of understanding teachers' initial experiences with remote teaching, given that they help to identify the challenges and facilitators for quality remote teaching.

Another aspect that teachers mention is the change in children's behavior. For them, not only the ERT, but the entire pandemic context, made children even closer to digital media. As mentioned by Patrícia (public school), "the report of screen use is very strong, as many children do not have other children to relate to and also have difficulty playing alone". This aspect generates a warning, because, according to Wang et al. (2020), the excessive use of technological devices influences stress and anxiety behaviors, as well as alterations in sleep and eating habits.

Furthermore, Carvalho et al. (2020) argue that the current health crisis triggers psychological problems such as anxiety, stress, and depression. This is due to psychosocial vulnerability, impacted by the long period of social isolation and the sudden change in the routine that was imposed on the population.

Filiz and Konukman (2020), searching in different locations of the world, believe that remote PE classes should aim to keep the student active and healthy. When implementing ERT, PE teachers faced the challenge of designing classes that could value student movement, even in this format, thinking about minimizing the side effects of social isolation on them. Lau exemplifies one of the possibilities for PE to act in this format:

There's a game that I don't know if you guys saw it, but I made it these days and it's great. You use your cell phone, open the camera and set the timer, then you press the button, put it somewhere, and during that time, all the children need to get out of the way of the cell phone before it takes the picture, when the phone takes the picture it will show who managed to hide and who couldn't. This is very cool because we bring a tool that children know well, with a game that we played a lot, mixing the two worlds and it gives a great result. (Lau, private school)

Vilchez et al. (2021), in a study with 15 teachers from California, in the United States, showed that all participants perceived the need to rethink creatively classes to suit remote teaching and worked online content with physical activities that required little or no equipment, such as yoga, dance, and the arts martial. Upon returning to face-to-face activities, these changes in behavior could also be observed as an outcome of the children's experiences during the ERT. Antônio (private school) reported that students started to show violent behavior that was not previously manifested. For this teacher, these attitudes are fueled by the period when the children were isolated at home. According to Bianca:

As the children have a lot of accumulated energy, they find it difficult to sit still while we explain the activities. They are always asking for free classes, because of this desire to express themselves freely, without necessarily complying with an established schedule, almost always arbitrarily, by adults. (Bianca, private school)

According to Wang et al. (2021), in China, schools did not prepare for the students' face-to-face return, as they expected that the return itself would solve the students' psychosocial problems. However, the authors state that in this initial moment of return, the negative impact of isolation is still present, with depression, aggression, compulsive behavior and hyperactivity. In the same sense, Felipe (public school) says that “the children spent a year saving all that energy, and now they want to let it go”. He states that he has not been able to teach classes “right”, as the students are so electric.

On the other hand, still on the return to face-to-face activities, there were teachers who highlighted the attention and willingness of children during classes as positive. In this perspective, Patrícia (public school) comments: “They arrived at the school with a strong desire to return to face-to-face activities. Most of the suggestions are made with joy, because of the contact they have again”.

This behavior is related to children's need to relate and play with their peers. After a year and a half of the pandemic, living with limitations in their interpersonal interactions, with all the fears, uncertainties, and concerns, children are even more in need of affection. In this perspective, Maria says:

Children are born with the need to interact, create, imagine and play. The pandemic will not stop this from manifesting in them. It may take them a while to feel what it's like to play without fear again, but I see that they will realize that there is something much better than what they experience today and that games and interactions can be much more real, true, and expressive. (Maria, public school)

Maciel (2011) emphasizes that inhibiting children's social life is an indication of risks that can cause damage to mental life in childhood. From this perspective, recreational activities, inherent to the human condition, especially in childhood, are fundamental in the field of mental health, since they have a structuring value that enables the re-signification of traumatic situations.

4.2 Application of safety protocols

The safety protocols that we have all had to adapt to since the beginning of the pandemic are intensified with the gradual return to face-to-face activities. Consequently, a series of actions and reorganizations had to be carried out by managers, teachers, and students. According to Lima and Oliveira (2021), in relation to safety protocols, there is currently no consensus between health and education professionals. This raises concern as to whether the shared environment will actually be safe for students, parents, and teachers.

The teachers investigated in this study perceive the application of the protocols as an additional challenge to be overcome in the face of COVID-19 and in the execution of their pedagogical practices. The challenges begin at the first moment, in the phase of preparation and training of teachers to teach in the situation of so many restrictions and protocols. On this theme, Lari comments:

I didn't have any training that prepared me for the pandemic, for the restrictions and limitations it imposed, we had to learn in practice. Training on what to do and what not to do is very limited because everything is very new. Plus, the protocols are always changing. (Lari, public school)

Considering that the pandemic is something new for everyone and that there are still doubts about what can or cannot be done, Lari continues her discussion by addressing the challenges of following the current protocols. She highlights the difference between PE and other disciplines:

The principal told me that the student needs to arrive on the court and remain in the same place for the entire class. In the classroom this works, because the student arrives, sits at the desk, and stays in the same place until the end. But how am I going to do this in a PE class? There is no way. (Lari, public school)

In the same sense, in a study by Varea et al. (2020), future teachers, from Spain, report missing the proximity with students during classes. They still believe that the new protocols, the constant cleaning, and distancing, affect students, generating feelings of fear, doubt and insecurity.

In the same way that teachers were not well trained to teach remotely, the lack of information and preparation is being reported in the process of returning to face-to-face teaching. Teachers have been placed in a turbulent situation, in which they have to adapt to a period of reorganization of the school system.

In the investigated context, different teaching situations were mentioned: some schools are dividing the face-to-face classes into weekly groups, A and B, for example, while other institutions, which have greater space capacity, are managing to attend everyone through rotations and stations. There are also schools where those responsible are preferring not to take students in person, requiring teachers to mix the two situations: classes taught in person with students in the classroom, and live transmission for children who are at home.

That is, in addition to the concern for everyone's safety, new demands and responsibilities overload teachers, who in addition to planning and putting into practice their classes, during the pandemic need to worry about guidelines and restrictions that change all the time. Ana also highlights the difficulty in planning activities without knowing how many students are going to attend classes, due to the increase in absences, resulting from this unstable scenario in which information fluctuates all the time:

We are never sure how many students will go to school. I do the planning and often I can't develop anything. It's very difficult, we don't know what to expect. There are weeks when everyone goes and I think I'll be able to continue the planning, but the next week they don't show up anymore. (Ana, public school)

The investigated teachers mention that, in addition to the reduction in the number of students due to the division into weekly groups, difficulties in accessing the necessary means for ERT, or the preference of those responsible, they also noticed an increase in the number of student absences and dropouts. Dropping out of school is a complex, multifaceted, and multi-causal phenomenon, which is related to personal, social, and institutional issues (Figueiredo and Salles, 2017). These aspects show the school as a space that influences society but is also influenced by it. Thus, during the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers were able to observe, in general terms, the worsening of the social and economic problems existing in Brazil, which affects students and their families.

On the other hand, the decrease in the number of students due to safety protocols also had its positive side. Saraiva (public school), for example, works at an institution that faces financial and administrative difficulties, which result in the limited availability of specific materials for PE classes. In his reality, the teacher mentions that the decrease in the number of students was a facilitator of the classes because for the classes of a certain sport he had only five balls “before I needed to make a relay of these balls among 25 children. Nowadays I can give each one a ball and can give them more supervision”.

In this aspect, teaching practice is positively influenced, as working with smaller classes, in addition to demanding fewer materials, makes it easier to diagnose the difficulties of each student, and allows the development of more individualized classes (Sousa, 2019). In this way, teachers who defend the positive aspects of having a small number of children praise the quality of care offered to them. Sol gives an example:

We are attending a maximum of 12 children, due to distancing. If it exceeds this number in face-to-face teaching, it becomes two groups, A and B. The service in this way is much better, it is possible to perform the same exercise several times, correcting the movements much more easily. (Sol, public school)

Sousa (2019) finds that, in small classes, the relationship between teacher and student becomes better when compared to regular classes, as the relationship tends to be closer and more exclusive. In addition, he points out that the behavior of students in this situation improves, as it becomes easier to control and predict situations of possible indiscipline.

It is evident that teachers are reinventing themselves every day, but in the case of a pandemic, the commitment of these professionals alone is not enough. Agreeing with Santos and Queiroz (2021), we believe that these teachers need to feel welcomed, requiring a collective movement that unites competent authorities, public authorities, family, school, and the entire network that makes up society. Such a movement must aim at overcoming adversities, as well as providing resources, physical spaces, and whatever else is necessary for the school to safely return to its face-to-face practices, in a structure prepared to welcome everyone in their physical and emotional needs.

4.3 Transformative Physical Education

The perceptions of school physical education teachers about their classes during the pandemic, highlight the importance of this discipline for children, above all, in the appreciation of movement and play. The reports about how special and liberating the face-to-face return of this discipline was to the students was unanimous among the teachers interviewed, as exemplified by Felipe (public school) “When I say that we are going to the court, the children are very excited, because they spend all the other classes inside the room. It is in the PE, then, that they go outside, that they spill over”.

It is through playing children develop motor skills, exercise their imagination, improve their relationship with the environment, in addition to putting into practice their ability to pay attention. In view of this, Severino and Porrozzi (2010) emphasize that the PE teacher, through their practices, must provide their students with experiences of playfulness, understood as an excellent tool for exercising citizenship. The discussions of Lau and Lari are illustrative in this perspective:

I pick up the groups from the classroom to take to the gym. Due to the protocols, in the other disciplines, they have to remain seated all the time, each one with their own material. When they arrive at PE, they free themselves, they want to play, to be close to the other children. It's like an escape valve. (Lau, private school)

In the school context, as a curricular component, it is in PE that games are more stimulated and developed. Although we know that spontaneous play is not limited to a space or time, and can manifest itself in different ways at school and outside it, Maria cites the differences she perceived in the children's play when returning to face-to-face teaching:

Children are playing with more real things. Words like “ICU”, “hospitalization”, and “medicine”, are entering their daily lives. I think that, because we see play as something so pure and docile, realizing that it is being influenced by the current reality generates concern. In addition, children are learning to play more on their own. Before, they played more collectively, they had more divergences, and more ways of playing. (Mary, public school)

According to Maciel (2011), playing is present from the earliest stages of development. For the child, being in contact with play is liberating, being a source of creativity. In agreement with this, Maria believes that “in childhood, playing is attributed to feelings of lightness, freedom and manifestations of expressions”. In this perspective, the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil, to a certain extent, prevented children from going to school and playing outside their homes, restricting time and space for valuable moments of relationships and interactions with the environment, with others and with themselves.

Upon returning to face-to-face teaching, subjects that previously did not provide opportunities for bodily and emotional manifestations, such as those in the exact sciences area, became even more theoretical and rigid due to safety protocols, since students must remain in the same place all the time, making it impossible to exchange experiences and collective activities. In this regard, Pedro mentions:

As of May, I was able to develop collective games again, as PE is the only time children have to be out of the classroom. I realized that they were very unmotivated, so I went to talk to the coordinator to include games so that they could have some kind of contact. She authorized it, as long as I sanitized all the equipment when changing classes. Now luckily the kids are excited and happy in my classes. (Pedro, private school)

Pedro's report exemplifies what was pointed out by Almeida et al. (2021): that the return to face-to-face classes would be complicated, as well as would require adaptations. Such adaptations need to be made in a humanized way in order to value and strengthen human relationships inside and outside the school environment so that this moment is another learning experience for everyone (Almeida et al., 2021). In this way, the perceptions of the teachers interviewed are in line with Severino and Porrozzi (2010), for whom, even if adapted to the new rules, PE is being seen by students as a special moment, in which the teaching and learning process becomes a pleasant practice, which awakens spontaneity, joy, and interaction.

5. Final Considerations

This study addressed the difficulties experienced in the pedagogical practice of teachers in the face of ERT, highlighting the lack of training for the use of information and communication technologies; lack of guidance from school management; difficulty in establishing contact with students; and lack of motivation of students to participate in classes.

Although teachers mentioned few training opportunities or guidance for appropriation of digital mechanisms, there were also positive reports regarding the use of digital technologies in this period, since it is a tool that enables the dissemination of knowledge and the participation of students in the processes of teaching and learning.

In turn, in relation to the resumption of face-to-face activities, establishments with insufficient physical space to respect social distancing were required to organize alternation strategies between groups, maintaining face-to-face and remote activities. In this way, the lack of consensus between health and education professionals stands out as a difficulty, resulting in norms and specifications that are often divergent.

The reduction in the number of students in face-to-face classes was a point that divided opinions. Possibly, these different perspectives are due to the numerous realities and contexts in which teachers work. Teachers who defend the positive aspects praise the improvement in the quality of care offered to each student. On the other hand, other teachers emphasize the difficulty in planning and developing activities without knowing how many students will attend classes.

In addition, teachers perceive in the interaction with their students and their families, that the spread of COVID-19 has restricted the possibilities of space for children to play outside their homes, in addition to making the valuable and important moments of social interaction at school impossible (at least for a period). When they were able to return to school, they were faced with safety protocols that oblige them to remain in the same place all the time, without exchanging experiences and collective activities. Thus, in the investigated context, with the return of classes, PE was manifested as the only time when children are out of the classroom, being perceived as a moment of liberation, in which teachers provide feelings of lightness, joy, and manifestation of expressions.

In view of these findings, it was possible to understand the experiences, anxieties, and learning that teachers had during the ERT and in the process of returning to face-to-face practices. Although the research results cannot be generalized, they provide us with relevant indications about how the COVID-19 pandemic can affect teaching practice. It is noteworthy, therefore, that Brazil is an unequal country, in which the different regions that compose it present very peculiar characteristics and profiles. Therefore, the context of this investigation represents a metropolitan region in southern Brazil. Also, due to the pandemic scenario faced during the data collection of this study, it can be cited as a limitation the fact that we did not have the possibility to do interviews with other social actors involved in the discussions undertaken (such as the children for whom the investigated teachers teach, as well as coordinators and employees of their educational institutions).

In this way, this possible limitation can also be configured as a suggestion for future studies, since opposing different points of view on the same phenomenon can be relevant for the expansion of the look that we so desire. Therefore, the identification of the different perceptions and feelings reported may contribute to reflections and overcoming contemporary and future challenges in different contexts. Thus, as possible applications and scope, the dissemination of the findings of this study may support pedagogical meetings in schools, aiming at minimizing the restrictions found, with a view to enhancing strategies that transform the current status. It is also suggested that similar investigations be carried out with other populations, expanding the understanding of how the environment can interfere with the experiences lived by teachers during this period.