1. Introduction

When considering the term evaluation, many people have various misconceptions. TenBrink (2003, p. 64) believes: “Educational evaluation is the systematic investigation, observation, and interpretation of information.” However, many teachers think of it as merely paper-pencil tests that focus on showing how many content students have mastered or not. Assessing is not only summative but also a considerable array of formative strategies such as asking students to explain their thinking. These strategies determine whether or not students are achieving the objectives proposed in the language classroom.

Assessment includes different strategies, like observation, that allow teachers to obtain reliable and more accurate clues about students’ progress. This means teachers need to be well-prepared in terms of assessing English as a Foreign Language (EFL) to make informed decisions about how to properly measure the learning outcomes that each student is supposed to achieve at a certain level.

Regarding learning how to evaluate English at the elementary level, students from the Bachelor (BA) “Elementary Education with a minor in English” at the University of Costa Rica (UCR), Western Campus, take an evaluation course that is taught in Spanish along with students from other education majors. It seems then that due to the mixed population, this course is not geared towards assessing a particular subject.

However, since the inception of the BA “Elementary Education with a minor in English,” no one has investigated how suitable it is to group these students with students from other majors, especially since the English Elementary Education students need to learn how to evaluate a foreign language.

Along these lines, it is known among the professors, who supervise the teaching practice, that one of the weaknesses of the student-teachers has to do with assessment from designing student observation checklists to written tests. From this situation is born the research aiming at exploring the need for creating an evaluation course taught in English and tailored to students enrolled in the bachelor’s degree “Elementary Education with a minor in English.”

2. Review of literature

This section describes what assessment is, its characteristics, current trends in the foreign language field, and suggested techniques and instruments. It is also important to pinpoint that the researchers could not locate previous studies about this specific issue.

2.1 Assessment

The words evaluation and assessment have caused ambiguity, confusion, and misunderstanding among teachers, whose native language is Spanish, because some of them are not aware of the characteristics that involve the assessment process and the factors that guarantee its success. On the one hand, Leahy, Lyon, Thompson, & William (as cited in Atalmis, 2018, p. 315) state: “Classroom assessment activities should aim at increasing the quality of learning in the classroom, rather than largely through the traditional sense of passing and failing the exams.” On the other hand, Carbajosa (2011, pp. 187-188) contrasts that: “The purpose of evaluation is no longer to discover a universal knowledge, but to capture the uniqueness of particular situations and their characteristics.” Given this, the concepts of assessment and evaluation are still blurred to some foreign language teachers, as those two words become one in Spanish.

The term assessment could refer to the level of knowledge prior to teaching, the product of the learning process, or the feedback provided to make amends in the learning process. O’Connor (2009, p.116) states: “Summative assessments are used to make judgments about the amount of learning.” Iamarino (2014, p.1) states: “[Formative assessment] concerns itself with the cohesive body of knowledge that the student gains as a result of the course.” Thus, while the primary purpose of the summative assessment is to gauge quality by measuring what has been learned, and judging it based on an overall grade, formative assessment is the reflection on the learning process itself. Therefore, assessment is a continuous process. It reflects not only on how the learning is going but also it helps the teacher identify areas of improvement for teachers and students.

In Spanish, the term “evaluación” encompasses both English terms “assessment” and “evaluation.” According to Tyler (as cited in Mondal and Mete, 2013, p.123) educational assessment is: “The judgment process for the educational goal... realized through education and class activities.” It is then through different instruments that teachers measure the students’ learning outcomes. At the same time, evaluation is considered a guided process that aims at bettering all the elements involved in a course from the students to the syllabus, where all participants including family, teachers, and community are meaningfully involved to enhance the learning process (Mateo, 2000; Ahumada,2001). This process requires systematization and looks for the accomplishment of the objectives that contribute to improvement.

2.2 Current views on evaluation and assessment of EFL/ESL

Several authors agree on the fact that evaluation and assessment for the learning of EFL and English as a Second Language (ESL) is changing. The teaching of foreign or second languages is witnessing a notorious shift to approaches that recognize that affective considerations need to be taken into account in the acquisition of EFL or ESL (Shaaban, 2005, p.16). Likewise, Valdez and O’Malley state: “There has been a growing interest among mainstream educators in performance assessment due to concerns that multiple-choice tests...fail to assess higher-order skills and other skills essential for functioning in school or work settings.” (as cited in Sumardy, 2017, p. 2). Therefore, if language-teaching views are changing, language assessment should also be modified.

Unfortunately, the assessment process is sometimes seen as a threat by teachers and students because it pinpoints what is wrong and what has not been achieved. However, from a positive perspective, it can be approached as to what can be improved regardless of whether the assessment is formative or summative.

It is important that both teachers and students view assessment as a formative and summative process used as a turning point to guide the teaching, and whose goal is to better serve the needs of the students. Bazo and Peñate (2007, p.66) believe that in primary education: “We must not forget that evaluation is a tool for teachers as well as an instrument that helps our pupils to construct the new knowledge they identify as ‘the English language.”

In terms of formative assessment, self-evaluation can motivate students about their learning process since they feel part of it and can assess their learning. Formative assessment aims at monitoring students’ progress and allows the teacher to provide feedback and re-teach what is needed. Bazo and Peñate (2007, p.67) suggest using a: “Progress diary [that] it is normally used at the end of each unit,” but it might be good to do it more often.

Students write and reflect on their progress by responding to the questions, in their native language, so they can elaborate their answers on whether they have attained the objectives or not. They could also tell what they can or cannot do, so far. Therefore, teachers can take advantage of this tool to find out if the teaching process is being effective.

Nevertheless, it is usual, at least in Costa Rica, to find language educators assessing students with only written exams, which tend to cause high levels of anxiety. Shaaban (2005, p.16) states: “The assessment of students’ progress and achievement in EFL/ESL classes should be carried out in a manner that does not cause anxiety in the students.” Sadly, this type of exams causes angst among students since they are expected to get a passing grade. However, this could be turned into a positive experience if “if children perceive assessment as an integral component of the learning/teaching process.” (Shankar, 2010, pp. 184).

It is then mandated that alternative formative assessment takes place since it is an ongoing process that does not wait until the end to give feedback to the student. Shaaban (2005, p.35) states: “[This type of assessment] take into account variation in students’ needs, interests, and learning styles; they attempt to integrate assessment and learning activities. Also, they indicate successful performance, highlight positive traits, and provide formative rather than summative evaluation.”

Alternative assessment then aims at pinpointing the strengths of both the students and the teaching process, and it also pursues to provide suitable strategies to diminish the students' weaknesses by considering their characteristics. At the same time, it gives the student the chance to reflect on their learning, reduces anxiety, and increases the feeling of success by focusing on communicative fluency.

Furthermore, alternative assessment techniques for young learners are performance-based and require students to perform authentic tasks. Foreign or Second language learners need to be introduced to the tasks. They require sufficient input and must be clear on what they are expected to do. Assessment has to be previously known by the learners as well. If the teacher is scoring the task performances holistically, the student performance should be measured against standards previously discussed in class (Shaaban, 2005, p.5). If learners are aware of the aspects that are going to be assessed during the task process, they will feel more confident when working on the tasks: “The assessment is most effective when students are given a copy of the rubric as an explanation of your expectations.” (Buttner, 2007, p 12.).

Some of the alternative classroom assessment techniques suggested are oral interviews, role-plays, written narratives, presentations, self-assessments, learning logs, dialogue journals, peer and group assessment, and student portfolios (Shaaban, 2005, pp. 19-22). This array of opportunities gives the students multiple options to show what they know in very different ways.

Nowadays portfolios seem to be a popular option as they provide students with the opportunity to show their most meaningful work. In this regard, Herrera et al. (as cited in Mussawy, 2009, p.19) consider portfolios: “incorporate the perspective of students and teachers about learning and assessment …[they] provide a longitudinal observation of student progress as they show incremental gains in knowledge, skills, and proficiencies.” In this way, language teachers and their students can see their growth from the moment the course starts.

Currently, another assessment instrument is the observation sheet. It can be used as a tool to record the linguistic progress of students. Bazo and Peñate (2007, p.70) suggest that teachers can: “include aspects they can observe every day in the classroom … [and] can be a valuable register of the linguistic and socio-cultural progress of our pupils”.

2.3 Assessing Guidelines for English Language Learning in Costa Rica

In Costa Rica, the English syllabus for elementary public schools’ states:

Learning English as a foreign language in Costa Rica will allow students to develop communicative competence, to gain knowledge of a new culture, new beliefs and attitudes as well as to develop their full potential in order to become productive members of Costa Rican society. (Ministerio de Educación Pública, 2005, p.18)

Therefore, learning English as a Foreign Language in this country is supposed to be an experience in which the learners deal with meaningful and purposeful tasks that challenge them to face simulated real-life situations in the target language; and in order to serve the students, teachers are expected to use the program as a guide to plan and assess the language classes.

In relation to assessment outcomes, the English program mentions: “The teacher chooses different tasks, which match both the objectives and the tasks from the plan that will be considered suitable for evaluating the students; [sic] language skills.” (Ministerio de Educación Pública [MEP], 2005, p.34). To comply with these expectations, language teachers need to carefully choose the assessment tasks since these should match how students were taught. There must be a correlation between the summative assessment and what was done in class. MEP believes skills have to be assessed in the same way they were taught. At the same time, several educational systems around the world are adapting to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, including Costa Rica.

The MEP states in the new English syllabus:

The purpose of studying English in the Educational System is the development of the learner’s communicative competence as well as the knowledge, skills, abilities, values, and competences of a 21st-century citizen. This requires the implementation of innovative communicative language teaching methodologies. These methodologies are supported by principles established in the Common European Framework of Reference for languages. (2016, p.21)

This means teachers should become familiar with these standards and know how to assess students so they can reach specific bands. In this regard, Bazo and Peñate (2007, p.71) mention that the use of portfolios is promoted as a tool to record the experience of learning a language. Portfolios promote lifelong learning, keep a record of the performance of linguistic abilities, and promote a socio-cultural conscience and a tolerant attitude towards other cultures and languages. However, at MEP (2009, p.23) portfolios are considered as an assessment tool only in secondary education.

The policy at MEP (2009, pp. 1-2) defines assessment as: “A process of passing value judgments made by the teacher, based on measurements and qualitative and quantitative descriptions to improve the teaching-learning processes and assign grades based on what the students have learned.” This definition encompasses both formative and summative assessment and the use of assessment tools to gather data and assign a grade.

Additionally, “the assessment of the learning process in cycles I and II requires an approach that goes along with the development of basic language skills for communication: speaking, listening, reading and writing.” (Ministerio de Educación, 2008, p.6). MEP also acknowledges that due to its distinctive characteristics, the acquisition of a foreign language implies the use of adapted assessing techniques.

As a result of previous considerations, MEP (2008, pp.7-8) has set the guidelines listed below for cycles I and II:

The assessment of a foreign language in cycles I and II is mainly based on performance in the target language.

The assessment instruments vary according to the goals and objectives set and must be known by the learners before tasks and tests are applied.

Assessment activities should be an extension of the pedagogical experiences the learner faces in the process.

To comply with these guidelines, English teachers need to plan tasks for students to perform no only as classroom activities but as summative assessments. These need to measure language skills and subskills according to the language goals or objectives of the English program.

Specifically, to assess the oral skill, the use of both holistic and analytical rubrics is encouraged. The first one is general and has a few levels of performance. It measures the assignment globally. The latter measures different criteria and the level of performance. The scores are added to reach the final grade (Ministerio de Educación Pública, 2008, p.17).

To assess the listening skill in the first cycle, the paper and pencil test is expected to be administered. It is appropriate for this level since reading and writing are hardly involved, mainly in first grade. This kind of test requires students to choose an answer using letters, numbers, or symbols.

Regarding summative assessment, Ministerio de Educación Pública (2009, pp.21-22) views it as the base for students’ grades and certifies what students have learned and achieved. Bazo and Peñate (2007, p.4) focus on tests and state that they can provide evidence of what students can do. Likewise, tests can also evaluate different aspects that are otherwise hard to observe in the classroom. At the same time, tests help teachers: “gain a more rounded view of the pupil’s achievements” and show teachers what content students are having difficulty with.

For Ministerio de Educación Pública (2011, p.6), “validity and reliability are two qualities inherent in any measuring instrument.” Therefore, the teacher must construct tests that guarantee these two attributes. Similarly, validity, reliability, language skills, and areas including spelling, contextualization, time, typing, students' foreign language level, instructions, and backwash effect are factors that must be considered in the construction of written tests (Saricoban, 2011, pp. 398-399). These aspects are vital in the construction of tests according to what and who teachers are teaching.

Regardless of what assessment instrument is used, the goal is to assess the students’ performance in relation to the objectives of the subject matter. Also, teachers need to keep in mind that: “the success of the learners is linked to the coherence between didactic planning, mediation activities developed in the classroom, techniques implemented and measuring instruments.” (Ministerio de Educación Pública, 2011, p.4). Bazo and Peñate (2007, p.67) coincide with the MEP policy that the items used in assessments, especially in tests should match the activities carried out in the classroom.

Based on the scenery mentioned above, the aim of this study is to explore the need for designing an evaluation course taught in English and tailored to the students enrolled in the Bachelor “Elementary Education with a minor in English” at the University of Costa Rica, Western Campus. At the same time, the research question and sub-question guiding this investigation are the following:

To what extent is the course ED0196 “Evaluation of the Learning Process in Early Childhood and Primary Education” suitable for the students in the Bachelor “Elementary Education with a minor in English”?

What is the relevance of the course ED0196 “Evaluation of the Learning Process in Early Childhood and Primary Education” in the training of primary school college students as future English as a Foreign Language teachers?

How appropriate are the objectives, content, and procedures of the course ED0196 “Evaluation of the Learning Process in Early Childhood and Primary Education” for the students in the Bachelor “Elementary Education with a minor in English” at the University of Costa Rica, Western Campus?

What are the weaknesses and strengths of the course ED0196 “Evaluation of the Learning Process in Early Childhood and Primary Education” in training students of the Bachelor “Elementary Education with a minor in English” at the University of Costa Rica, Western Campus?

3. Method

3.1 Approach

This study used a qualitative research design as it: “is best suited to address a research problem in which you do not know the variables and need to explore. The literature might yield little information about the phenomenon of study, and you need to learn more from participants.” (Creswell, 2014, p.16).

In this case, researchers found literature regarding how to evaluate English as a foreign language, and also examined the 2016 syllabus of the course ED0196 “Evaluation of the Learning Process in Early Childhood and Primary Education,” but it was also necessary to find out if the current evaluation course taken by students in the Bachelor “Elementary Education with a minor in English,” at the University of Costa Rica, Western Campus, meets their needs.

At the same time, the study was exploratory in the sense that the population has never been asked about their perceptions on the usefulness of the course ED0196 “Evaluation of the Learning Process in Early Childhood and Primary Education,” so the researchers needed to listen to the participants and build an understanding based on their experiences (Creswell, 2014, p.61).

Therefore, a phenomenological research design was taken into account to make sense of the experiences of the participants, regarding assessing English, by conducting interviews (Creswell, 2014, p.42). This investigation was carried out in 2016.

3.2 Participants

To collect information for this research, the population was organized into two groups (student-teachers and former students) and three individuals (two MEP authorities and one experienced elementary school teacher with ample experience in assessment). The student-teachers and former students from the BA have similar experiences, but the latter has more teaching experience in either private or public schools.

“In qualitative research, we identify our participants... on purposeful sampling, based on ...people that can best help us understand our central phenomenon.”(Creswell, 2014, p.42). For research purposes, the student-teachers, that participated in this study, were being supervised, at the time, by at least one of the head researchers. The former students were chosen based on their experience and closeness to the university campus, whereas MEP authorities and the elementary school teacher were chosen based on their experience and knowledge dealing with either assessment or the teaching of English.

Thirteen student-teachers and nine former students from the BA “Elementary Education with a minor in English” participated in this study under the condition that they had taken the course ED0196 “Evaluation of the Learning Process in Early Childhood and Primary Education” at the UCR-Western Campus, in the last five years previous to this study, but in different semesters. The researchers set the five-year time requirement to make sure that the course was about the same when both the student-teachers and the former students took it.

Three experts provided their insights about what and how the evaluation course is or should be taught. One of them is the MEP authority in English, who manages, coordinates, and supervises educational, technical, and administrative activities carried out in public educational centers. The second expert is a MEP authority in assessment, who oversees how to guide, and train teachers concerning assessment matters. The third expert is an elementary school teacher with 25 years of experience in assessment in primary school who also has experience teaching the ED0196 course.

Although neither of the two MEP authorities has taught the course ED0196, MEP is the largest teacher employer in Costa Rica, and they both are in charge of supporting the language teachers in terms of assessment and teaching English.

3.2.1 Description of the course ED0196 “Evaluation of the Learning Process in Early Childhood and Primary Education”

The course ED0196 “Evaluation of the Learning Process in Early Childhood and Primary Education” focuses on analyzing the importance of assessing the learning process from a critical and analytical perspective. The content covers assessment generalities, which includes concepts, principles, characteristics, stages, types, and functions. The relationship between objectives and assessment is also studied in the course as well as the importance of assessing students with curricular accommodations.

The objectives of the course vary from choosing assessment techniques and instruments, based on the objectives and specific skills of the subject, designing different learning assessment tools, and analyzing the curricular accommodations applicable to students with educational needs.

Part of the course content contributes to the understanding of qualitative and quantitative assessment, and it includes techniques for developing informal assessments and portfolios. The course also provides tools for designing observation instruments, rubrics, checklists, written tests, and performance and behavior logs.

In the bibliography section, there are many sources for students to look up information related to assessment. The syllabus contains a list of additional sources that students can consult to expand their knowledge. Also, the reference list has two sources that are aimed at assessing EFL.

3.3 Instruments

Instrument 1. It is a semi-structured interview that was conducted in English and administered to a group of nine former students from the BA “Elementary Education with a minor in English.” It initially had eight open-ended questions, but the number of questions varied based on the details of the information provided. To start the interview, the researchers asked several questions to build rapport. The following questions were about their insights on how useful the content of course ED0196 “Evaluation of the Learning Process in Early Childhood and Primary Education” was, based on their current teaching experience.

Instrument 2. It was a semi-structured interview that was conducted in English and administered to a group of thirteen current student-teachers of the BA “Elementary Education with a minor in English.” It initially had seven open-ended questions, but the number of questions varied based on the details of the information provided. Most questions were about their viewpoints on how useful the content of course ED0196 “Evaluation of the Learning Process in Early Childhood and Primary Education” was based on their current teaching experience as student-teachers.

Instrument 3. It was a semi-structured interview that was conducted in Spanish and administered to an elementary school teacher with 25 years of experience in assessment in primary school. It initially had four open-ended questions, but the number of questions varied due to the details provided in the answers. Most questions were about the teacher’s experience in assessment at the elementary school level.

Instrument 4. It was a semi-structured interview that was conducted in English and administered to a MEP authority in English. It initially had six open-ended questions, but the number of questions varied due to the details provided in the answers. Most questions were about the experience clarifying doubts about teaching English at the elementary school level as well as her viewpoints related to how English is assessed in the foreign language classroom, and the way in which the course ED0196 “Evaluation of the Learning Process in Early Childhood and Primary Education” is taught.

Instrument 5. It was a semi-structured interview that was conducted in Spanish to a MEP authority in assessment. It initially had six open-ended questions, but the number of questions varied due to the details provided in the answers. Most questions were about the experience when dealing with elementary English teachers in regard to assessing EFL. She was also asked for her opinion about the way the course ED0196 “Evaluation of the Learning Process in Early Childhood and Primary Education” is taught.

3.4 Procedures

Data was collected by conducting one semi-structured interview for each participant. The researchers administered the instruments within a four-week period and each interview lasted between thirty to sixty minutes. The researchers designed the informed consent required to notify participants about the purpose of the research as well as key aspects of the investigation.

Participants were either contacted personally or by phone to ask them to participate in this research project. The researchers scheduled an appointment with each participant from each sample group to carry out a face-to-face interview. In this meeting, the consent was explained and provided to the participants before the questions were asked.

The conversation was recorded and based on the questions of the semi-structured interview, although some questions were added as the conversation went along. The first couple of questions were asked to build rapport with the interviewees. The interview for former students and student-teachers of the BA “Elementary Education with a minor in English” were carried out in English.

However, the researchers used Spanish sporadically to clarify some questions and interviewees did as well in some of their answers. The interview for one of the MEP authorities was carried out in Spanish since the person does not speak English. The interview for the other MEP authority was carried out in English since the person is proficient in the language.

3.4.1 Data Analysis Procedure

The data was organized and transcribed, using a word processor, to start the coding process. The first step was to read the transcript of all the interviews according to the subgroups of participants: student-teachers, former students, and experts. This way the researchers could get a general idea of the information gathered. Some ideas were highlighted, and the text was divided into segments.

Codes, which are “labels used to describe a segment of text,” (Creswell, 2012, p. 244) were given to these segments to reduce the ones that were overlapping. The codes were organized into themes. That helped organize and analyze the data based on the emerging codes found in the discourse, which eventually answered the research questions. For research purposes, eleven themes were analyzed in the results section, and although it might look like some codes are repeated, they were treated from a different perspective.

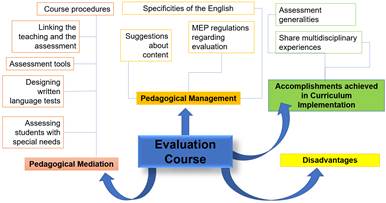

After analyzing the information, the researchers used Figure 1 to display the findings and a detailed description of each of the themes which in this case are interconnected to better describe the tortuosity of the phenomenon.

Finally, to validate the accuracy of the findings, the researchers triangulated the information. “Triangulation is the process of corroborating evidence from different individuals,” (Creswell, 2012, p. 259) which in this case refers to the information provided by the experts, student-teachers, and former students of the evaluation course along with the syllabus of the course.

4. Results

The following section discusses the salient findings of this research and interprets their implications, particularly with respect to the research question: to what extent is the course ED0196 “Evaluation of the Learning Process in Early Childhood and Primary Education” suitable for the students in the Bachelor “Elementary Education with a minor in English”? Several commonalities were found among all the interviewees. Figure 1 summarizes the results and then in the following subsections, the major themes are discussed in detail.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on the information provided by the participants, 2016.

Figure 1 Summary of the results of the evaluation course ED0196, UCR-Western Campus, Costa Rica, 2016

4.1 Accomplishments achieved in the curriculum implementation

4.1.1 Assessment generalities

Both the former students and the student-teachers believed that they did not receive enough accurate training on assessing EFL learners. They maintain that they were introduced to assessment generalities, regardless of the subject matter, and did not focus on how to evaluate language skills in English. The syllabus of the course states, “the assessment generalities (concepts, principles, characteristics, stages, types, functions, modalities) will be studied,” and that is corroborated by Participant 004 who said: “Regardless of what major we are in, we all have an idea of how to evaluate students in general.”

Also, according to the syllabus of the course, the contents are divided into six units which include a total of forty-three subtopics studied within sixteen weeks. Hence, if the number of topics and subtopics the course is considered, along with the fact that the course ED0196 is catered to students from four different education majors, it can be inferred that the course focuses on assessment generalities.

Participant 002 stated: “in the course ED0196, I received a general overview of the most important aspects to take into account when assessing students. However, I have to say that sometimes, more time was needed to cover all the topics in depth.” Both former students from the BA “Elementary Education with a minor in English” and student-teachers’ perception is that the contents were not studied thoroughly, hence affecting their current assessment instruments design. Participant 002 mentioned: “I’ve faced issues when designing tests to assess different production skills, implementing the English formative assessment for first grade, and using other types of assessment tools.”

The MEP authority in assessment agrees with the students since he/she believed that in-service teachers (graduated from the program) lack knowledge in the specificities of how to evaluate a foreign language. However, at the same time, this authority pointed out that students from four educational majors can be together in an evaluation course to go over generalities as long as they part ways at some point to learn about their particular field.

Thalheimer (2018, p.14) states: “knowledge is composed of more meaningful constructs, including concepts, principles, generalizations, processes, and procedures,” which confirms that if handled correctly, all students can learn different ways to evaluate and learn from it as long as they transfer that knowledge to their core subject correctly.

However, the experienced elementary school teacher does not consider it appropriate that four educational majors take the same evaluation course together, but by the same token he/she stated that, “Many of the content units of the course are assessment generalities, and they are useful for primary and preschool majors.”

In this sense, the researchers agree with the comments stating that because the course has students from four different majors, the only way to meet the needs of all students is concentrating on generalities disregarding specific needs. However, this is detrimental to their training as professionals in education.

It is important to note that the MEP authority in English pointed out, “there is not a special regulation for the English program and its specificities, so in that sense, they [teachers] have to adapt certain items and elements to the REA [Reglamento de Evaluación de los Aprendizajes].” In other words, students must master the principles and specificities of assessment in general, especially because most official country-wide guidelines are written in Spanish and the teachers are the ones who must adapt those principles to evaluate English as a language.

Both the former students and the student-teachers admitted to having questions related to how-to formative assess first-graders and adapting assessment instruments for language learners. The course syllabus devotes three content units to formative assessment, performance assessment techniques, and the MEP guidelines for assessment [REA]; and still, several interviewees do not feel they learned enough about these topics.

4.1.2 Share multidisciplinary experiences

According to the syllabus of the evaluation course, most assignments are done in pairs. This setting allows students to learn from their classmates mainly because they are from other majors and the assessment in other core subjects is different. Participant 002 stated: “The course is enriched by having experiences and different points of view of the topics because of the different majors.” The student-teachers and the former students agreed that learning assessment generalities and sharing experiences with students from the three other majors are viewed as advantages of the course since their perspective expanded as they complemented each other through group work.

The MEP authority in assessment also believes that having students from different majors in the same course helps them learn from each other by sharing experiences and constructing knowledge. Along these lines, the elementary school teacher also confirmed that as a result of this mix, students get acquainted with different types of assessments and instruments administered at distinct levels and subjects in early ages. The latter thinks the course provides English Elementary Education students with the opportunity to hear about others’ ideas and gives them the chance to adapt the tools to their subject area.

Learning from others depends on people’s ability to integrate their own and others’ experiences. In order to do that successfully, people have to abstract from single experiences (that they themselves or others have had) and recognize those features that different situations have in common. (Moskaliuk, Bokhorst, and Cress, 2016, p.69)

However, they do not always learn how to adapt assessment tools correctly. Regardless, once these students enter the workforce, no matter if it is a public or private school, classroom and language teachers have to work together as a team and follow the guidelines given by MEP.

4.2 Pedagogical mediation

4.2.1 Course Procedures

The course is described as both theoretical and practical, however, most of the specific objectives in the syllabus aim at ‘analyzing…’ This is a possible reason why former students commented that they received a lot of theory and devoted a lot of time working on reading assignments. For instance, Participant 005 commented: “I consider that some topics related to assessment need to be emphasized and practiced more and not just giving the theory.”

Even though the procedures described in the syllabus allude to a class that provides both theory and practice, most former students and the student-teachers agreed that they had faced difficulties when writing instructions and designing written and oral tests, test questions, and rubrics.

It is important to, “design directions to maximize clarity and minimize the potential for confusion,” (Educational Testing Service, 2009, p. 21). Thus, it is imperative that English Elementary Education students get acquainted with the use of the language in formal assessments. One example is the statement of Participant 019: “I didn’t get enough practice during the course, so when I began working everything was a chaotic whirlwind.”

The biggest concern then is that designing assessing instruments is part of any teacher’s job, and although it requires to know the theory, without practice, English Elementary Education students miss the opportunity to acquire knowledge and ask questions that come up during the process of constructing instruments. Students also miss the chance to feel confident when assessing. Thus, when they start working and face their reality, they might have to either research by themselves, or ask “experienced teachers” for guidance when possible.

4.2.2 Linking teaching and assessing.

The MEP authority in English confirmed one common problem in teaching has to do with how students are taught and how they are assessed. There is a mismatch between the teaching process and the assessment. “Assessments [should be] designed so that the content of the assessment matches the content of the instruction.” (Atlantic City Schools, 2014, p. 11).

The MEP authority in assessment went a little further and commented that complaints about the written tests are common because the teachers neither follow the MEP guidelines nor make a connection between the way the subject is taught and the way it is evaluated on the written tests. He/she assures us that, “the classroom procedures have to be integrated with the evaluation process,” and that, “there must be consistency between the way in which [a student] is taught and evaluated. This refers to the principle of representativeness.” Therefore, the assessment tools must resemble the classroom teaching-learning activities so that students would not be shocked when being evaluated. Both MEP authorities made the same comment.

The syllabus of the course states as one of the general objectives to infer the importance of administering assessment techniques and tools according to the purposes, objectives, specific skills, or procedural content. However, since students in the course ED0196 can construct the assessment tools in Spanish, they do realize how detrimental this is for them until they are in the practicum or even after that when they enter the workforce. If the goal is to match the assessment technique to specific skills, among others, students in the BA are not attaining this objective since they are designing assessment tools in Spanish and not based on the MEP syllabus.

Participant 022 pointed out: “The course should be more focus[ed] on teach[ing] how to establish a connection from objective to an assessment form.” This participant understands the importance of how daily work and summative assessment should match to avoid discrepancies between how students are taught and how they are asked to perform in a test. Therefore, all these comments seem to prove that by the end of the course ED0196, students have not internalized the importance of being coherent between the way the language is taught and the way the language is evaluated.

Other student-teachers mentioned they had problems in the practicum when they were assigned to teach listening and speaking but asked to use a written test to assess those skills. Consequently, elementary school students usually have a hard time answering questions in the test since there is no link between the teaching process and the way the language skill is assessed.

4.2.3 Assessment tools used in teaching

The student-teachers and the former students believed that they did not receive sufficient training on designing scoring rubrics. They admitted to having difficulties assessing EFL when rubrics were needed because they did not know how to design them in English. Moreover, the student-teachers stated that they did not learn how to write indicators which are essential to designing scoring rubrics. Overall, designing different types of rubrics was the main difficulty former students faced when they started working as EFL teachers.

In addition, the MEP authority in English mentioned that one of the most common drawbacks in the course has to do with designing rubrics. To make matters worse, the MEP authority in assessment mentioned that students, who graduated from the BA “Elementary Education with a minor in English,” do not know how to construct neither indicators nor valid and reliable instruments.

Also, the syllabus of the evaluation course states that students will construct different assessment instruments according to the purposes, objectives, specific skills, or procedural contents for preschool or primary education.

Evaluation includes alternative assessments, which are usually designed by the teacher to gauge students' understanding of material. Examples of these measurements are open-ended questions, written compositions, oral presentations, projects, experiments, and portfolios of student work… Evaluation will also include authentic assessment practice such as the following: Observation, essays, interviews, performance tasks, exhibitions and demonstrations, portfolios, journals, teacher-created tests, rubrics, self- and peer-evaluations. (Atlantic City Schools, 2014, p. 11)

Students were expected to design the assessment tools mentioned above based on the needs of the English class. However, that is not the case in this course. Therefore, this objective is not met because the course as-is would need to have four professors who can guide students on how to design specific instruments and learn the techniques needed for each major.

4.2.4 Designing written language tests

Student-teachers mentioned that they did not learn how to construct tests, test questions nor instructions for an English test while others indicated that one of the most useful content units of the course was designing written exams. The former students concurred with the latter. However, the MEP authority in assessment mentioned that students who graduated from the BA “Elementary Education with a minor in English” do not know how to construct written tests properly.

It is important to note that no matter what the subject is, a written test is used to measure quantitatively the degree of mastery of learning. Nationwide, teachers administer written tests, regardless of whether they work for the public or private educational system. Nevertheless, “paper-and-pencil tests no longer cover the variety of activities and tasks that take place in the elementary classroom.” (Shaaban, 2005, p. 16).

According to the syllabus of the evaluation course, students learn about the parts of a test, how to design one with at least three types of items along with the respective specifications table. Nonetheless, the MEP authority in English stated: “Most of them [teachers] have a hard time with assessment (tests, approved items, etc). It seems like the university does not teach MEP’s regulations exclusively and even use certain assessment items that are not allowed at schools.” This is a serious problem because, regardless of the type of school (public or private), all of them are obligated to follow MEP’s regulations.

Researchers believe the professor teaches how to design a written test, but because students are not required to do it in English, they are not acquainted with the difficulties that might arise when designing an English test. For example, Participant 020 commented: “The most difficult situation was to work with ‘tabla de especificaciones.’ … At UCR we never focused on using these tools. That is why when I was asked to do it, I felt confused, and I needed a lot of help.” The problem is not only that students are not taught what they need to know to succeed as English teachers, but also that the contents of the course are not tailored to their needs.

4.2.5 Assessing students with special needs

The goal of the curricular accommodations is to adjust the teaching and learning process to meet the individual characteristics, differences, and needs of students with special needs. They can be non-significant or significant.

The primary goal of testing accommodations is to ensure that they have the same opportunity ... to demonstrate their knowledge or skills ...As a general principle, testing accommodations are intended to benefit examinees that require them while having little to no impact on the performance of students who do not need them. (Educational Testing Service, 2009, p. 30)

In this regard, one concern among the student-teachers was not knowing how to adapt assessment instruments for students with special needs. Participant 004, for example, said: “I have had difficulties when working with curricular accommodation cases. I [do not know] how to evaluate significant and non-significant necessities, how to deal with special cases.” At the same time, the MEP authority in English acknowledged that former students from the BA “Elementary Education with a minor in English” have difficulties when adapting the curriculum under these circumstances and that the most common drawbacks have to do with dealing with curricular accommodations and leveling.

Although the evaluation course syllabus aims at analyzing the curricular accommodations in the field of education, the UCR students do not seem to learn how to specifically modify the assessment tools for the foreign language class. Therefore, while the evaluation course students seem to learn the basics for curricular accommodations, since they do it in Spanish, it does not apply to the English class, and students do not know how to transfer that knowledge. As a result, students from the BA do not attain that objective in the evaluation course.

4.3 Pedagogical management

4.3.1 Specificities of the English language

In the description section of the syllabus of the evaluation course, ED0196, it is explicitly stated that the course is tailored to teach about assessment processes in the field of education for preschool and primary school majors. Specifically, there is no reference for the assessment processes needed to assess English as a foreign language. Although the English Elementary Education students are expected to know to create and administer instruments, to assess both macro and micro-skills of the target language, no goal is achieved regarding this matter.

In a more in-depth analysis of the syllabus, the researchers realized that two objectives relate to building different learning assessment tools and analyzing different types of tests. However, although many participants in this study claimed that they studied about oral and written tests and indicators, they could be constructed in Spanish. Eventually, this type of practice is not very useful because it does not apply to English. “The first step in developing a test item should be to link, ... the content and skill that the item is supposed to measure.” (Educational Testing Service, 2009, p. 20). Thus, the major’s needs are not met in reference to how to evaluate English.

Also, although the course has a wide variety of resources about assessment that students can look up, the mandatory reference list of the course syllabus does not include any resources for the English Elementary Education students. The bibliographical list does not guide them to find theory nor assessment tools used to evaluate EFL. In fact, the additional reference list of the syllabus includes only two documents from MEP regarding assessing English. Researchers believe that because these books are specific to the foreign language field, they should be included in the mandatory book list.

Moreover, according to the former students and student-teachers from the BA “Elementary Education with a minor in English,” they did not learn and practice in-depth how to assess English as a foreign language because the focus of the course is on assessing the other core subjects taught at the primary level. In this regard, the elementary school teacher agrees with them. Participant 005 mentioned: “We don’t learn the specific assessment of our major.” Participant 021 stated: “You have to look for more information from people who are working as English teachers or from different sources.” Participant 022 said: “Even though I am working in a school, I still have many questions, and sometimes I have to ask an experienced English teacher or my supervisor how to evaluate an objective accurately.”

Researchers believe this situation lowers the confidence of the student-teachers and rookie teachers. That is why, based on their experience as practicum supervisors, they can tell the student-teachers always ask, either the practicum-seminar teacher or the supervisor, questions about assessment. In the meantime, former students try to find mentors that can help them clarify their questions.

4.3.2 MEP regulations regarding assessment

The course syllabus states as its general objective to analyze the legal foundation of assessing learning in cycles I and II of general education. In this regard, Participant 002 assured: “Students in the course ED0196 analyze the REA.” The experienced elementary school teacher added: “In primary, MEP requires to use measuring instruments.” Students must be familiar with the REA because those instruments must be designed based on it.

However, the MEP authority in English acknowledged that former students from the BA “Elementary Education with a minor in English” are not familiar with MEP’s regulations, and therefore most of them struggle with applying MEP assessment policies. He/she commented: “Many former [students] do not study… MEP regulations in-depth, which affects their performance within the public system.” The MEP authority in assessment agrees with his/her colleague adding that former students from this specific BA: “seemed not to be acquainted with MEP regulations,” and “most of them struggle with applying MEP assessment policies.” It is then clear that the way the REA has been taught or analyzed is not working.

Based on the experience as practicum supervisors and the interviews, the researchers learned that in the evaluation course students do not use “el programa de estudios del MEP de inglés” (the English syllabus) to base their assessment tools. The MEP English syllabus provides the necessary information needed to design rubrics and tests. In other words, the cognitive targets, language objectives, or goals are already established.

However, in the specific case of the rubrics, these, “should make clear the role that English language skills should play in determining a score” (Educational Testing Service, 2009, p. 28). In order to do that, the assessment tools should be based on the official objectives or goals established for the language, which are not grammar. Therefore, not basing the instruments on a random topic or grammatical aspects of the language, which is not allowed at MEP.

Thus, although it is known what the MEP requirements are, students in the course seemed to have the freedom to construct test questions, a written test, and other instruments in Spanish, which will be useless during the practicum or after they graduate. Participant 010 explained that for the written test: “The professor gave ideas about topics, so we chose a topic we felt comfortable with.” Therefore, the student did not see the need to use the official “programa de estudios del MEP” to complete this assignment. Hence, it is contradictory not to ask students to contextualize their assignment since it is detrimental to their professional development.

By the time most students from the BA “Elementary Education with a minor in English” take the evaluation course, they are proficient enough to design all assessment tools in English. Doing this will get them to practice specific traits of the language and be more acquainted with MEP objectives, content, procedures, and guidelines.

4.3.3 Suggestion about contents for an evaluation course taught in English

The student-teachers pointed out that if the UCR were to offer an evaluation course specifically for the BA “Elementary Education with a minor in English,” the contents should include how to administer different formative assessment techniques, particularly in first grade. “Teachers should strive to familiarize their students with all forms of assessment because each form has its merits and uses, as well as its problems and shortcomings.” (Educational Testing Service, 2009, p. 23). If pre-service teachers learn about different types of assessment, it is expected that they will use them in the classroom.

However, it is interesting that although the current evaluation course’s syllabus includes it, it does not seem to be working. The MEP authority in assessment also commented that teachers do not promote peer-assessment nor self-assessment.

The MEP authority in assessment also pointed out that the students need to be taught how to design rubrics. The student-teachers pointed out it is necessary to learn about rubrics to grade daily work and homework. Similarly, the former students suggested that the design of rubrics for oral presentations and written production should be included as part of the content if there were a course designed and addressed to students from the BA “Elementary Education with a minor in English.” No matter what the purpose of the rubric is, students need to learn how to design rubrics in English and for the English class.

The student-teachers and the MEP authority in assessment also pointed out that the students must be taught how to write indicators, which are needed to evaluate the level of accomplishment of the English learners. They also agree on having the evaluation course students learn how to design oral and written tests in English by a specialist in both English and assessment. Finally, the former students agreed on including the assessment of curriculum accommodations as a part of the content if a new course were to be designed.

4.4 Disadvantages of the course

On the other side, the student-teachers agreed that one disadvantage of sharing the course was that they did not receive specific instruction on how to evaluate English as a Foreign Language. The MEP authority in English also considered the commingle of students from four educational majors as negative because the English Elementary Education students need to focus on assessing the process and the functions of the target language. In addition, the former students mentioned that having non-contextualized examples, insufficient training, and the lack of a teacher who is proficient in English were the three main disadvantages of the course.

On this last matter, the student-teachers mentioned that the professor was not able to give accurate feedback and therefore could not sufficiently meet their needs, particularly when they had specific questions. Apparently, the professor asks for outside help to grade one of the assignments, which is to design a test. Participant 014 stated: “There was one activity in which we could design an English test and the teacher of the course had to give it to an English teacher he trusted to evaluate it.”

They think this problem arises because the professor neither speaks English nor is a specialist in assessing EFL. In this sense, the elementary school teacher agrees with the statement and adds that the professor is not a specialist in assessment in early education either. Araya and Córdoba (2008, p.6) state: “English teachers’ expertise in their discipline goes beyond the knowledge and application of theories, principles, concepts, technical skills, and methodologies.” However, one downside of the professor of this course is that these minimum requirements are not met to teach about how to evaluate a foreign language. As a result, when questions arise in the class, the professor can only answer questions based on the experience of teaching the course.

Additionally, students talked about how difficult it was for the professor to manage and teach in-depth details of the assessment of each education major. Participant 009 stated: “The professor cannot cover the necessities of all four majors.” In this sense, the constraints of the course, lack of time, and knowledge of the teacher on how to assess a foreign language is an issue. The question is, can the university find and hire a professor with experience in the field of education with four different degrees, and that is also proficient in English?

The MEP authority in assessment commented that even if one only thinks about two majors, preschool and primary education, the assessing methods in these two levels are worlds apart, and it is almost impossible to find an expert in general education assessment and English as a foreign language both in preschool and primary. In fact, this authority pointed out that MEP has a different syllabus for each level and that they do not necessarily match in either content or procedures.

5. Conclusions

Based on the findings, in spite of the high relevance of the course, ED0196 (UCR-Western Campus), as-is is unsuitable for students from the BA "Elementary Education with a minor in English" because it does not teach in-depth how to evaluate English as a Foreign Language. That is a problem since, in Costa Rica, diagnostic, formative, and summative assessment is an on-going process throughout the school year. Therefore, students are not graduating as competent in the assessment of a foreign language as they should rendering a knowledge gap in their training.

Researchers also determined the syllabus of the course ED0196 is inappropriate for the major since many of its main components do not completely fulfill the need of assessing English. Although students go over the assessment generalities, they are unable to transfer that knowledge to assess English as a foreign language, leaving specificities of the language to be learned once they start working.

Moreover, there seem to be more weaknesses than strengths in the course because even though students learn about many instruments and assessment criteria, many of them are not tailored to the English class and they are not taught how to apply the general rules of assessment in the foreign language field. Therefore, there is a need for creating a course that caters to the needs of the students from the UCR-Western Campus BA “Elementary Education with a minor in English.”

It is clear that the university has two routes. One is to redesign the course so students who have not yet taken it can benefit from the changes or design a new course for the current students who are being trained to become English as a Foreign Language teachers. Consequently, these college students will be better prepared to start the teaching practicum and then enter the educational field with more confidence in terms of assessment.

Finally, the researchers hope that the results of this research serve as evidence for the self-assessment and accreditation process that the major is carrying out to graduate students better prepared to face the challenges of assessing English as a Foreign Language in both private and public schools.

As for further research, researchers recommend implementing a mixed-methods approach so that the instruments can provide both text and numerical data. In order to do that, it is necessary to extend the time frame of the research study and to locate and interview more participants. The researchers also suggest that a similar mixed-method research study be conducted with students from the BA “Educación Preescolar con concentración en Inglés” who also take the course ED0196 and might be facing similar challenges.

In a new study, researchers need to foresee some limitations similar to the ones faced in this investigation. The researchers had difficulty identifying and meeting with suitable participants because gathering the ideal number of former students was a challenge. When students are double majoring (primary and high school) and had taken the evaluation course for high school first, then they did not have to take the one for primary (ED0196). This combined with the fact that, since graduating, many former students moved out of the area making more difficult to get in touch with them. However, if taking the necessary precisions, the data gathering process can be smoothly carried out.