Introduction

Given their impact on the progress of nations, the effects of entrepreneurship are a subject of study. Entrepreneurship acts as an economic motor, creating new jobs, increasing market efficiency through improved competitiveness and promoting development in different areas, as well as encouraging innovation (Amorós, Fernández and Tapia, 2012, p. 250; Baumol, 2004, p. 36; Minniti, 2012, p. 23). Despite strongly linked to the cultural traits of each country (Morrison, 2000, p. 62), entrepreneurship is a tool that can generate social inclusion in the long-term (Goel and Rishi, 2012, p. 50).

The positive effect of education on the entrepreneurial activity has been confirmed by the literature (Delmar and Davidsson, 2000, p. 1). Therefore, many universities have included in their programs content and initiatives aimed at promoting cultural change among students. This demonstrates that universities place value on the entrepreneurial option as an alternative to personal and professional development which encourages a relationship between students and the productive sectors. This way, students would be capable of making positive contributions to the society and economy in which they are located. Moreover, educated entrepreneurs have an advantage given their specialized knowledge (Dickson, Solomon and Weaver, 2008, p. 249)

However, in order to encourage entrepreneurship, it is important to know first how the decision to begin a business is formed. Methodologies for addressing this research topic have experienced changes over time. Initially, authors studied certain personality traits associated with entrepreneurial activity like the need to achieve and later, other works analyzed the importance of demographic characteristics. These studies have been widely criticized (Ajzen, 1991, p. 206; Santos-Cumplido and Liñán, 2007, p. 98) for their methodology, conceptual limitations, and low explicative capacity. Furthermore, some authors focused on the study of entrepreneurial opportunities and understood them as positive and favorable circumstances lead to entrepreneurial action, which may arise from prior knowledge, social capital, cognition/personality traits, environmental conditions, alertness, and systematic search (George, Parida, Lahti and Wincent, 2014, p. 328).

From a third perspective, given that the decision to be a business owner could be considered voluntary and plausible (Krueger, Reilly and Carsrud, 2000, p. 415), we consider it necessary to study how that decision was made. In this way, different behavioral theories and models are employed to find more about the factors that influence entrepreneurial conduct (Carpi and Breva, 2001, párr. 5). Some recent studies have dealt with the relationship between enterprising behavior and university students (Espíritu and Sastre, 2007, p. 112; Flores and Palao, 2013, p. 382; Liñán, Rodríguez-Cohard and Rueda-Cantuche, 2011, p. 208; Veciana, Aponte and Urbano, 2005, p. 180). In this context, we aim to identify how entrepreneurship education influences student’s entrepreneurial intention.

This work is structured as follows: first, a review of the literature on entrepreneurship education is conducted. Then, a model based on the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991, p. 182) is proposed and, finally, the results of the model are analyzed and discussed.

Literature review

Entrepreneurship education

In the last few years, entrepreneurship education has gradually gained a relevant position in society, as entrepreneurial abilities are considered generic competencies that lead to better future performance, especially when individuals face the labor market (Pring, 2004, p. 107). Departing from the above, there is evidence that entrepreneurship education is necessary in the curriculum due to its impact on society and the benefits it brings to students. In connection, Flores and Palao (2013, p. 379) have indicated that the need of economic growth and employment creation faced by the current economies makes it indispensable to integrate entrepreneurship education skills into all fields of study. And this integration may be achieved through the implementation of participative and creative techniques, such as microenterprise creation or business simulation in education.

Nevertheless, the line of research on entrepreneurship education remains an insufficiently explored field (Guzmán and Liñán, 2005, p. 152; Liñán, 2004, p. 152; Toledano, 2006, p. 804). Furthermore, empirical evidence provided by different studies fails to demonstrate unanimously whether continuous education stimulates or discourages the willingness of students to undertake entrepreneurial activities (Oosterbeek, van Praag and Ijsselstein, 2010, p. 452; Peterman and Kennedy, 2003, p. 138; Sánchez and Pérez, 2016, p. 16; Tkachev and Kolvereid, 1999, p. 278). Other studies, like the one conducted by Joensuu-Salo, Varamäki and Viljamaa (2015, p. 863), have shown that in students, both the initial level and decreases in entrepreneurial intention do not affect the development of these intentions. Likewise, Lima, Lopes, Nassif and da Silva (2015, p. 12) obtained similar results in their analysis, which indicates that business education has a negative impact on entrepreneurial intention and perceived self-efficacy.

However, the studies carried out by Rae, Martin, Antcliff and Hannon (2012, p. 398) and Lanero, Vázquez, Guitérrez and García (2011, p. 121) propose the opposite. Rae et al. (2012, p. 398) concluded that business education might potentiate entrepreneurial skills, while Lanero et al., (2011, p. 1212) analyzed the effect of entrepreneurial education on different students, finding a positive effect on entrepreneurial spirit and perceived feasibility.

Other studies have not been able to define the role of entrepreneurship education. At the national level, Poblete and Amorós (2013, p. 173) conclude that higher education does not affect entrepreneurship, while the work of Cabana-Villca, Cortés-Castillo, Plaza-Pasten, Castillo-Vergara and Álvarez-Marin (2013, p. 65) revealed that the potential entrepreneurial capacity in Chile is mainly determined by students’ attitude and attributes. Furthermore, Amorós and Abarca (2014, p. 23) point out that demographic variables govern entrepreneurship.

Although these scientific studies did not reach the same conclusion regarding the impact of entrepreneurship education, the results obtained by some authors have confirmed that education allows students to recognize entrepreneurial opportunities and gives them more determination when they intend to undertake an enterprise (Von Graevenitz, Harhoff and Weber, 2010, p. 104). In other words, being aware of the determination to create a business and consciously planning its implementation in the future (Soria-Barreto, Zuñiga-Jara and Ruiz, 2016, p. 328).

According to Valencia, Montoya and Montoya (2015, párr. 17), several authors have addressed entrepreneurship from the study of entrepreneurial intentions, arguing that psychological traits and personal attributes have proven unreliable as indicators of entrepreneurship. Instead, intentions are the best indicators of predicted behavior. The broad majority of research on entrepreneurial education has been based on Ajzen’s findings (1991, p. 181), who proposed the theory of planned behavior to explain the entrepreneurial intention of individuals.

Theory of Planned Behavior

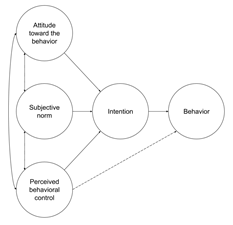

The theory of planned behavior posits that all human behaviors are planned and preceded by behavioral intention (Mokhtar and Zainuddin, 2011, párr. 5). In this sense, the theory proposes three components that predict this behavioral intention (Do Paço, Ferreira, Raposo, Rodrigues and Dinis, 2011, p. 25), namely the attitude towards or desire for the proposed behavior as well as the global positive or negative appraisals people make before displaying a specific behavior; the social and subjective norms that consider the proposed behavior of other people; and the perceived control or feasibility of the proposed behavior.

The theory of planned behavior can be applied to diverse voluntary behaviors and produces positive results in different fields, including the selection of a professional career (Ajzen, 2001, p. 44). In this way, this theory is suitable to analyzing how creating a business plan or taking entrepreneurial training affects intentions (Kautonen, Van Gelderen and Tornikoski, 2013, p. 698; Krueger and Carsrud, 1993, p. 327). Many of these studies are focused on university students, such as Espíritu and Sastre (2007, p. 112), Flores and Palao (2014, p. 382), Lanero, Sánchez, Villanueva and D’Almeida (2007, p. 4), Liñán et al. (2011, p. 197), among others. This theory proposes that entrepreneurial intention is a previous and determinate element in the realization of planned behaviors for future entrepreneurs (Lanero et al., 2007, p. 2). Attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavior control and mediate the relationship between perceived entrepreneurial motivation and entrepreneurial intentions (Solesvik, 2013, p. 265), as shown in Figure 1.

Source: Ajzen, 1991, p. 182.

Figure 1 Theory of Planned Behavior in the form of a structural diagram

Unlike other models, the theory of planned behavior offers a generally applicable and coherent theoretical framework to understand and predict entrepreneurial intentions based not only on personal but also on social factors (Fayolle, Liñán and Moriano, 2014, p. 681). This is demonstrated through the varied body of evidence in the literature, which clearly expresses that this theory is the tool of analysis most used for studies on entrepreneurship. According to Valencia et al. (2015, párr. 43), researchers widely recognize the relevance of this theory, especially in the modelling of entrepreneurial intentions based on teaching and contextual learning processes.

A study conducted by Kolvereid (1996, p. 53) on Norwegian students from a business school illustrates this point. The author concludes that the experience of self-employment, gender and family background indirectly affects the intention of self-employment through its effect on attitude, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control. Likewise, Tkachev and Kolvereid (1999, p. 278) found that in a group of university students in Russia, attitude, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control determine intention when choosing a job.

In the same line, Fayolle, Gailly and Lassas-Clerc (2006, p. 703) reached the conclusion that programs for entrepreneurship education have a positive impact on the entrepreneurial intention of students. Nevertheless, this impact is not significant for perceived controlled behavior. In addition, Wu and Wu (2008, p. 772) validated the model for the theory of planned behavior through a study conducted on Chinese students and concluded that university education explained entrepreneurial intention.

Another study supporting the application of this theory to entrepreneurship education was carried out by Van Gelderen et al. (2008, p. 538), who showed that, for a group of university students from the Netherlands, the most important variables in explaining entrepreneurial intention was being alert as an attitude and financial security as an expression of the perceived controlled behavior. In connection, Yang (2013, p. 367) proved the validity of the theory of planned behavior through work carried out at Jianxi University of Finance and Economy. In this work, attitude was the most effective predictor of entrepreneurial intention, followed by subjective norms and perceived behavioral control.

Despite the diversity of studies aimed at predicting the entrepreneurial intention of students by means of the theory of planned behavior, little research has been conducted on the role played by universities or the curriculum of study programs on the decision of students to start a business. There is a growing consensus that university plays a role in the education of entrepreneurs (Krauss, 2011, p. 31). However, the way in which this spirit should be promoted from the University is an insufficiently treated subject (Martín, Hernangómez and Rodríguez, 2005, p. 131).

In this sense, Martínez de Luco and Campos (2014, p. 168) indicate that universities can work on promoting a positive attitude towards entrepreneurship by means of education on entrepreneurial awareness. Furthermore, perceived entrepreneurial self-efficacy would be reinforced if students were encouraged to apply the knowledge acquired on the economic-financial, legal, negotiation and communication fields to the creation and management of a company, promoting risk assumption in a responsible way.

Thus, in order to model the development of entrepreneurial intentions through teaching and contextual learning processes, this study incorporates other related variables to the model proposed by the theory of planned behavior.

Proposed Model

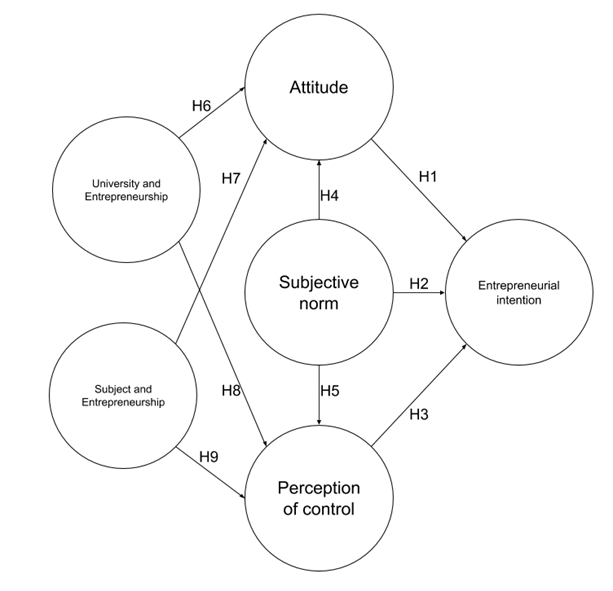

Upon an extensive review of the literature, we found that the link between subjects studied at university and entrepreneurial intention has not received enough attention. A model based on the theory of planned behavior is thus proposed (Ajzen, 1991, p. 182). This model comprises of nine relationships plus two latent variables related to entrepreneurship education, as shown in Figure 2. According to Contreras Serrano (2016, p. 2), the model can be validated using structural equations to elucidate the effect of university education on entrepreneurial intention.

The first construct is University and Entrepreneurship (UE), which considers the support students perceive from the institution, regardless of the program they attend. The second variable, Subject and Entrepreneurship (SE), corresponds to the student’s individual study plans, and not to the programs or organisms controlled by an institution, such as business incubators and financing, among others. In addition, these variables are expected to influence entrepreneurial intention through Attitude and Perception of Control.

Methodology

This article is an explanatory study that seeks to determine the impact of two education variables on entrepreneurial intention using the theory of planned behavior. To carry out the study, a two-stage methodology was developed. The first stage is qualitative and focuses on the review of secondary sources in order to create a model and hypothesis, while the second stage is quantitative and aims to confirm the relationships proposed in the model through the use of primary sources by using structural equation model. These primary sources are surveys applied to students from a Chilean university. Data collection was performed through non-probabilistic sampling by convenience using a semi-structured questionnaire sent to the institutional mail of a total universe of approximately 5 000 students during October and November 2014. A total of 583 surveys were completed. Subsequently, the sample was characterized and then a reliability analysis of the scales in the questionnaire was performed. Finally, an analysis of structural equations was carried out to study the influence of education on the entrepreneurial intention based on the Theory of Planned Behavior. In this stage, IBM SPSS Statistics v22 (IBM Corp, 2013) and IBM SPSS Amos v22 (IBM Corp, 2013) software were used.

The first qualitative exploratory stage, the literature review, contributed to the development of the proposed model. In other words, it helped to identify the variables in measuring entrepreneurship education as shown in Table 2, and the variables for assessing the theory of planned behavior in entrepreneurship, which are attitude, perception of control, subjective norm, and intention, as shown in Table 1. After this stage, the model in Figure 2 was generated to answer how education, both in terms of context and subjects studied, affects entrepreneurial intention.

As stated before, the final quantitative stage of the study was the application of the survey. This survey was applied in Chile, where according to Mandakovic, Abarca and Amorós (2016, p. 10), 26% of adults aged 18 to 64 consider themselves early-stage entrepreneurs, while 8.5% classified themselves as established entrepreneurs (businesses established more than 42 months ago).The instrument was sent to the email of engineering students from Universidad Técnica Federico Santa María, an institution that is strongly oriented to work with entrepreneurs through the 3IE Institute, and the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Office, where any student is able to develop his enterprises.

The survey consists of dichotomous and multiple-choice control questions, such as sex and subject studied, as well as the scales that looked to measure the constructs established in the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991, p. 182) and the variables of education in entrepreneurship as five-points Likert items. In the case of the TPB questions applied to entrepreneurship, variables were based on the Entrepreneurial Intention Questionnaire (Liñán and Chen, 2006, p. 20; Liñán et al., 2011, p. 212), which measures the four dimensions proposed by Ajzen (1991, p. 182). The final combination of scales has the advantage of showing high levels of internal consistence. In the literature, this model has been carefully developed by researchers such as Krueger et al. (2000, p. 423).

Table 1 Items used to measure Entrepreneurial Intention and TPB concept.

| Entrepreneurial Intention |

|---|

| I’m ready to do anything to be an entrepreneur |

| My professional goal is to become an entrepreneur |

| I will make every effort to start and run my own business |

| I’m determined to create a business in the future |

| I have thought very seriously about starting a business |

| I have the firm intention of starting a business some day |

| Perception of Control |

| Starting a business and keeping it running would be easy for me |

| I’m prepared to start a viable business |

| I can control the creation process of a new business |

| I know the necessary practical details to start a business - I know how to develop an entrepreneurial project |

| If I tried to start a business, I would have a high probability of succeeding |

| Attitude |

| Being an entrepreneur implies more advantages than disadvantages to me |

| A career as an entrepreneur is attractive to me |

| If I had the opportunity and resources, I’d like to start a business |

| Being an entrepreneur would greatly satisfy me |

| Among various options, I’d rather be an entrepreneur |

| Subjective Norm |

| My close family would approve of my decision to start a business. |

| My friends would approve of my decision to start a business. |

| My colleagues and coworkers would approve of my decision to start a business. |

Source: Own elaboration, 2019.

For the educational dimensions, namely Subject and Entrepreneurship and University and Entrepreneurship, a compilation of earlier works was formulated (Lüthje and Franke, 2003, p. 139; Martínez de Luco and Campos, 2014, p. 167; Moriano, Palací and Morales, 2006, p. 75; Todorovic, McNaughton and Guild, 2011, p. 134).

Table 2 Items used to measure University and Entrepreneurship and Subject and Entrepreneurship concepts.

| University and Entrepreneurship |

|---|

| With the education received at the University, I could start a business in the future. |

| The education I received at the University has made me interested in taking risks. |

| The education I received at the university has helped me to better understand the role of entrepreneurs in society. |

| The education I received at the university has helped me to implement entrepreneurial projects. |

| Since I entered college, I consider the idea of creating my own business to be closer. |

| Subject and Entrepreneurship |

| I believe that practical courses have given me more tools to start a business. |

| When teachers refer to or give examples about the professional future of the students, do students prefer to found a new company than be the manager of an existing one |

| The courses supply the necessary knowledge to start a new business. |

| The courses promote leadership skills necessary to start a new business. |

| The courses promote social skills necessary to start a new business. |

| Faculty members encourage students to seek practical applications for their research |

Source: Own elaboration, 2019.

Based on the literature review, the proposed model was built as shown in Figure 2, with the following nine hypotheses:

H1: Attitude positively influences Entrepreneurial Intention.

H2: Subjective Norm positively influences Entrepreneurial Intention.

H3: Perception of Control positively influences Entrepreneurial Intention.

H4: Subjective Norm positively influences Attitude.

H5: Subjective Norm positively influences Perception of Control.

H6: University and Entrepreneurship positively influences Attitude.

H7: Subject and Entrepreneurship positively influences Attitude.

H8: University and Entrepreneurship positively influences Perception of Control.

H9: Subject and Entrepreneurship positively influences Perception of Control.

Data analysis was carried out to corroborate the reliability and validity of the scales, determining whether the constructs gave an adequate account of entrepreneurial intention. The analysis was carried out using Cronbach’s alpha and confirmatory factorial analysis for each one of the six latent variables in the model. The proposed model was then assessed by structural equation modeling, namely, reviewing the statistical significance of each proposed relationship, analyzing the standardized regression weights of those significant relationships (p-value ≤ 0.005), and analyzing the goodness-of-fit statistics of the hypothesized model under test, according to Byrne (2001, p. 78).

Results

Among the respondents, 55% were male and 45% were female, equaling to 318 and 265 surveys, respectively. Most students were in the middle or late phases of their university program, with 129 in the fourth year, 118 in third year, 101 in fifth year, 61 in second year, 60 in first year, and 28 students from their sixth year of study.

Internal consistency analysis

The internal consistency of the scales was measured through Cronbach’s Alpha, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3 Internal consistency of the proposed scales in the model.

| Dimension | Cronbach’s Alpha |

| Entrepreneurial Intention (EI) | 0.909 |

| Attitude (A) | 0.859 |

| Perception of Control (PC) | 0.887 |

| Subjective Norm (SN) | 0.888 |

| University and Entrepreneurship (UE) | 0.873 |

| Subject and Entrepreneurship (CE) | 0.890 |

Source: Own elaboration, 2019.

According to the results, the six latent variables: entrepreneurial intention, attitude, perception of control, subjective norm, university and entrepreneurship, subject and entrepreneurship, all have a positive reliability scale (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.8) , in fact, none of the latent variables increased their Cronbach alpha when removing any of the observable variable.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

A confirmatory factor analysis was performed to corroborate the measurement model and test the proposed hypotheses, evaluating the degree that the observable variables explain the latent variables, then evaluating each proposed causal relationship shown in the hypotheses by reviewing the statistical significance through p-value and relation through standardized estimate. This procedure requires several steps, such as data preparation, specification and identification of the planted model, estimation of parameters, and the evaluation of the model’s fit. Finally, the model was evaluated to be within the range of absolute fit, incremental fit, and parsimony according to the literature.

According to Byrne (2001, p. 78) and based on the GFI and AGFI values reported in Table 4 (0.887 and 0.868, respectively), we can conclude that the proposed model fits the sample data fairly well, as they take values close to 1.00. Then the NFI and RFI values reported (0.863 and 0.850, respectively) derived from the comparison of our proposed model with the independence model, indicates that the model fitted the data in the sense that the proposed model adequately described the sample data, as they take values close to 1.00. The Parsimony Goodness-of-Fit Index (PGFI) that takes into account the complexity of our proposed model shows a value of 0.760, and that is consistent with GFI and AGFI. Finally, RMSEA value (0.077) indicates a reasonable error of approximation in the population (RMSEA<0.8).

Table 4 Selected AMOS Output for Hypothesized Model: Goodness-of-Fit Statistics.

| Fit statistics | GFI | AGFI | NFI | RFI | PGFI | RMSEA |

| Default model | 0.887 | 0.868 | 0.863 | 0.850 | 0.760 | 0.077 |

Source: Own elaboration, 2019.

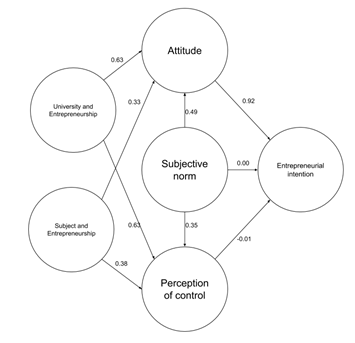

According to the results in Figure 3, and after reviewing the p-values in Table 5, the only direct predictor of Entrepreneurial Intention is Attitude (β = 0.92). Therefore, H1 is proved and H2 and H3 are rejected. In addition, Subjective Norm (β = 0.49), University and Entrepreneurship (β = 0.63), and Subject and Entrepreneurship (β = 0.33) have an indirect effect on the Entrepreneurial Intention of students through Attitude. Likewise, University and Entrepreneurship (β = 0.63) has a stronger effect than the Subject and Entrepreneurship (β = 0.33) on the Attitude. This is consistent with the results for Perception of Control, in which University and Entrepreneurship (β = 0.63) has a greater impact than Subject and Entrepreneurship (β = 0.38). Thus, H6, H7, H8 and H9 are accepted and H5 is rejected.

Table 5 Standardized regression weights and p-value of the proposed structural model

| Relation | Standardized Regression Weights | p-value |

| PC ( UE | .63 | *** |

| A ( UE | .63 | *** |

| A ( CE | .33 | *** |

| PC ( CE | .38 | .004 |

| A ( SN | .49 | *** |

| PC ( SN | .35 | .008 |

| EI ( A | .92 | *** |

| EI ( PC | -.01 | .021 |

| EI ( SN | .00 | .027 |

Source: Own elaboration, 2019.

(note: according to IBM SPSS Amos v22 *** means p ≤ 0.001).

Source: Own elaboration, 2019.

Figure 3 Standardized regression weights of the proposed structural model.

In contrast to the relationships proposed by the Theory of Planned Behavior, and according to the results of this study, we can assert that a direct predictor of Entrepreneurial Intention is Attitude, while Perception of Control did not show a significant relationship with Entrepreneurial Intention. This implies that, if education seeks to enhance students’ Entrepreneurial Intention, this is achieved through Attitude. At this point it is important to remember that the items used to measure the variable attitude are “Being an entrepreneur implies more advantages than disadvantages to me”, “A career as an entrepreneur is attractive to me”, “If I had the opportunity and resources, I’d like to start a business”, “Being an entrepreneur would greatly satisfy me”, and “Among various options, I’d rather be an entrepreneur”. This has practical implications in the relationship between education and entrepreneurial intention, since promoting a positive attitude towards entrepreneurship in students is of the utmost importance.

Subjective Norm also was found to have an effect on the intention to start a business through Attitude. This entails that the support a student perceives from other people around him or her indirectly affects the behavior towards attitude. It is important to understand that entrepreneurship is relevant in a general sense and not only in its relation to university students. In this way, encouraging enterprising activities has a direct effect on attitude towards entrepreneurship, because of the importance of the environment in motivating and facilitating entrepreneurial activity (Leitch, Hazlett and Pittaway, 2012, p. 738). These results support the idea that the opinion of friends, family and colleagues positively influences entrepreneurial intention through attitude. In other words, if the immediate environment reinforces a positive attitude toward entrepreneurship, students would exhibit greater entrepreneurial intention. Therefore, entrepreneurial intention could be deemed as a social phenomenon that is directly related to education.

Regarding the two variables of education, both are influential on Entrepreneurial Intention through Attitude. Despite having less impact, subject is still relevant to the model, given that support from university, as an institution and by subject, is an influential factor for the Entrepreneurial Intention of university students. Therefore, Attitude, in this case entrepreneurial attitude, should be fostered in order to encourage trust in business ownership and boost the motivation to start a business. The literature closely related this variable to the role of the university, because the task of higher education should go further than techniques and theory and translate into more practical courses, such as entrepreneur lectures and entrepreneur fellowship (Li-li and Lian-sen, 2015, p. 210).

In this sense, it must be noted that for Attitude, the observable item best evaluated in the questionnaire was “If I had the opportunity and the resources, I would like to start a business”. Therefore, entrepreneurship education should focus on helping students find opportunities and present different funding sources existing in the entrepreneurial ecosystem, as well as desirable career options that bring recognition and media coverage to them.

This finding represents both a theoretical and practical contribution to the field. From a theoretical perspective, the results of the study proposes a modification to the TPB based on the fact that the entrepreneurial intention of the students depends exclusively on attitude. However, although perceived control of behavior would not affect entrepreneurial intention, it could be important for the continuity of an enterprise over time. Likewise, the extension to the TPB proposed in the present study suggests that both university and entrepreneurship, as well as program and entrepreneurship, positively affect the attitude towards entrepreneurship. Thus, from a practical point of view, an ecosystem that supports and strengthens the attitude of university students towards enterprises should be generated both at the program and university levels. As mentioned above, the main practical effect of this would be to raise awareness of the opportunities and resources available to start a business.

In another vein, the Perception of Control variable has an effect on other phases of entrepreneurial conduct, for example, on start-up implementation or business. This is likely because more technical knowledge and entrepreneurial skills are related to this variable. To support this assumption, the literature reviewed indicates that ventures started by university students have better results than those started by non-university students in terms of employability, size and reach of the business, as well as its level of innovation, technology, and dynamism. In fact, higher education in individuals positively affects the decision in creating a company (Fairlie and Robb, 2009, p. 379).

Conclusions

The main theoretical contribution of this study is to suggest that the only direct predictor of entrepreneurial intention is attitude. This is consistent with the results obtained from Yang (2013, p. 373) and indicate the same correspondence between variables for the same model used in this study. The results therefore suggest that an essential task for universities in delivering educational programs on entrepreneurship is to promote a positive attitude towards students’ entrepreneurial activities. Initiatives that encourage trust in enterprise ownership and boost motivation to start a business are key to fostering environments that encourage entrepreneurship as a viable future option. Likewise, Martínez de Luco and Campos (2014, p. 168) express that universities can promote positive attitudes toward entrepreneurship through education in business awareness.

In this scenario, attitude in educational establishments is not only important for the promotion of entrepreneurial intention. Support from the immediate environment of students is crucial in building positive attitudes towards entrepreneurial spirit. As shown in the results, primary intention contains a potent social factor, that is, the support perceived by students from people around indirectly affects their behavior toward attitude.

Results also suggest that the business environment created by universities, for instance, in formal training under a formal subject or profession, has an impact on the student’s entrepreneurial intention. Consequently, since the effects of these two educational variables on attitude and perception of control were positive, universities should assess their programs to find whether they are undertaking the right approach to entrepreneurship. The following question arises from this context: are universities providing students with the knowledge or skills necessary to generate perceived control of entrepreneurial behavior? If so, efforts are insufficient if the attitude towards entrepreneurial spirit is not improved.

From another perspective, the results indicate that organisms linked to education should play an active role as trainers and sources of information. Educational policies and programs on entrepreneurship should introduce students to different funding alternatives and help them search for business opportunities that increase the control of perceived behavior. Moreover, formal education, both through subjects and an entrepreneurial environment, should promote a positive attitude towards entrepreneurship, showcasing it as a desirable career option and give it recognition and media coverage in order to also reduce fear of failure and improve the perception of entrepreneurship, which are key according to Amorós and Abarca (2014, p. 30).

In conclusion, our study has some limitations worth mentioning. First, theoretically speaking, delving into the exact variables that explain the attitude towards entrepreneurship is not possible. Second, although the hypotheses proposed were reviewed, they cannot be extrapolated, nor generalized, as non-probabilistic sampling was used to test the relationships proposed by the model. As mentioned above, all respondents were engineering students and therefore results do not represent a general context for university entrepreneurship but are limited to and partly representative of engineering students across Chile. And finally, there is no data on how many subjects or complementary training activities related to entrepreneurship that respondents have participated in and thus we could expect the existence of different clusters within the sample, which would condition the analysis performed.

As a proposal for further research, we suggest studying attitude in entrepreneurship through a longitudinal design to determine how education, both at the subject and university levels, can influence this attitude and confirm its role in entrepreneurial intention. Furthermore, a statistically representative study would allow us to test the model propose and perform a segmentation analysis based on participation in and knowledge of topics related to entrepreneurship.