Introduction

The proposals of different national and international institutions support the inclusive school and insist on the need to train teachers to achieve the full educational and social participation of all children, particularly of traditionally excluded social groups.

In the Spanish context, diversity is probably the main characteristic of educational centres. Therefore, it is necessary to raise awareness about the diversity of classrooms, which is derived from individual differences in terms of capacity, culture, religion, gender, etc., in order to find adequate educational responses within the framework of a teacher training model (Arnáiz Sánchez, 2012; López López, 2012; Rosselló Ramos, 2010; Sotés et al., 2012; Torres González, 2012; Torres, & Fernández-Batanero, 2015). Blanco (2006) considers that, for teachers to become inclusive, it is necessary to make important changes in their training, such as preparing them to make institutions open to diversity, to carry out their duty in different contexts and realities, and, lastly, to acquire theoretical and practical knowledge about the most relevant educational needs, strategies of attention to diversity in the classroom, curriculum adaptation, differentiated evaluation, etc. In this sense, Asensio Muñoz and Ruiz de Miguel (2017) and Sánchez-Sánchez (2016) referred to the need to generate spaces that allow linking the theoretical knowledge to the teaching practice and the specific training required by the teaching performance.

In the international scope of education, Horne and Timmons (2009) studied some variables that influence the development of inclusive education, such as professional development and the additional planning time required by inclusive education. Other authors have analysed the international trend toward inclusive education, such as Ruijs et al. (2010), who studied the relationship between inclusive education and the academic and socioemotional performance of students. Ainscow and Sandill (2010) analysed the organizational conditions needed to carry out inclusive education, giving essential consideration to leadership in the fostering of inclusive cultures. In this sense, Medina Revilla et al. (2017) provided new views about teaching-learning processes, assuming different approaches, among which it is worth highlighting innovative practices and teaching training perspectives, framed within communication between cultures, where inclusive education is. Laluvein (2010) referred to practice community as a didactic social model from which to approach problem solving. Ainscow (2012) provided some lessons, by analysing the international research focused on making schools more inclusive. Ainscow et al. (2012, p. 198) insist on the need to rethink the school duty and mentioned the “ecology of equity” to make schools more effective for everyone. In this line, Azorín Abellán (2018) understands that the ecology of equity puts education in a scenario where the local community acquires leadership and where inequities can be attributed to some school practices that might not consider student diversity, thus it is necessary to approach teacher training in the key of inclusion.

Teachers need to work in collaborative environments characterised by mutual support, shared responsibilities and systemic reflection (Krichesky, & Murillo, 2018). The educational response to diversity is a challenge for centres and for the educational community that must be incorporated in the institutional projects and in the inclusive educational practices. In this context, it is necessary to know the opinions of teachers about the inclusion of differences in the classroom, as well as their training needs. Therefore, we decided to work with practising teachers, since their teaching experience could be a reference to guide the training of new teachers. Barrantes-Montero (2015) pointed out the convenience of training teachers in transdisciplinarity, framing teacher training within the systemic paradigm. The previous work that is most immediately related to the present study is that of Ausín Valverde and Lezcano Barbero (2012), who elaborated a dossier about educational inclusion based on educational programs designed for foreign students. They analysed different educational programs, with the Teacher Training Program being the most valued one.

Methodology

This is a descriptive study, as it is designed to generate a system of indicators from a referential framework, and the methodology used was based on a qualitative research approach. The study is also retrospective (or ex-post-facto), since it is based on past events, and it uses narrative research, which in our case has two major roles: a) it provides ways of interpretation, and B) it provides guidelines for action (Bolívar et al., 2001).

This work is part of a larger research project, whose main objective is to know the opinions of teachers about inclusive education and their training needs, with the aim of determining some quality indicators that can guide the training of teachers in the key of inclusion. Other secondary objectives, although not necessarily less relevant for the investigation, were the following:

To know the opinions of teachers about inclusive education and its theoretical-practical link.

To analyse the relation between inclusive education and current reforms.

To know the training aspects that teachers need to acquire in order to meet the demands of inclusive education.

To propose quality indicators to guide teacher training in the key of educational inclusion.

The methodology is based on the use of an open-ended questionnaire applied through interviews. This technique allowed obtaining a general and broad view of the perceptions of the interviewed teachers regarding educational inclusion, contrasting relevant aspects, and delving into other central aspects for the investigation. In the process, we were able to follow the characteristic steps of descriptive research:

Formulating the research problem, determining whether the descriptive methodology is suitable and setting out the objectives.

Identifying the categories and sub-categories, and determining the proper techniques for data gathering.

Finding and contacting the population. The participants of the study were 16 teachers, of whom 8 were from early childhood and primary education and the other 8 were from secondary education, baccalaureate and training modules.

Designing the interview and having it validated by a group of experts.

Applying the previously designed data gathering instruments, i.e., questionnaire and interview.

Gathering, analysing and interpreting the data, and drawing conclusions.

The research question is focused on inclusive education and its practical implications. Preparing research instruments involves designing a set of questions whose aim is to specify ideas, beliefs or suppositions of the research team regarding the study topic. The phases to create the instruments of the present study were the following:

First phase: we conducted a thorough review of the specific literature on inclusive education, which was organised into three major blocks:

Block 1: International rules about education.

Block 2: Spanish and Andalusian regulations.

Block 3: Review of the literature on inclusive education.

The work method followed in this first phase was the Analysis of Axiological Content (Bardin, 1996) and the subsequent conceptual scheme. We understand that content analysis is one of the techniques that best respond to the research demands on written documents, and very adequate for working on educational documents. The process to study the documents was the following:

Selection of educational documents based on the following criteria: impact at the international scope, involvement in an education for everyone, interpretation at the national level, and specification at the regional level.

Analysis and critical evaluation of the document.

Consensus to tackle questions and uncertainties that may arise from studying the documents.

Second phase: preparing the instruments. The phases for preparing the questionnaire and the interview gather the criteria for the construction of both instruments, and they were organised as follows:

Creation of a bank of questions, 321 in total, that gather the doubts and uncertainties about inclusive education and its development in practice.

Grouping of the questions by categories, which set the topics of interest for the research, and sub-categories of analysis, which specify and delve into the established categories, as is shown in Table 1:

Table 1: Categories and sub-categories

| Categories | Subcategories |

|---|---|

| Meaning of inclusion | Meaning of inclusive education (MIE) Deficiencies of inclusive education (DIE) |

| Involvement in inclusion | Educational inclusion and practice (INC/PRAC) Disposition of centres (DISP) |

| Teachers and inclusion | Teacher training (TRA) Actions of the centre (ACT) |

| Students and inclusion | Inclusive education for everyone (IEFE) Educational inequalities (INE) |

| Inclusion and reformation | Re-structuring of centres (RST) Rethinking inclusion (RTH) Change of paradigm (CHA) Improving the quality of educational inclusion (IMP/QUA) |

Note: Developed by author.

Definition of categories

Meaning of educational inclusion: fundamental ideas of inclusive education, ethical principles that support it and deficiencies of educational inclusion.

Involvement in educational inclusion: disposition of educational centres to respond to the objectives that make sense of educational inclusion, and the democratic and equitable reasons that justify them.

Teachers and educational inclusion: aspects related to the training of teachers for these to meet the demands of educational inclusion, personal keys to improve the educational practices and promote inclusion in the common framework of basic competences of compulsory education, and commitment with the values of inclusion gathered in the planning of the centre.

Students and educational inclusion: educational inclusion is intended for all students, understanding that differences can turn into inequalities and that the quality of education must be targeted to every student.

Educational inclusion and reformation: the link between inclusive education, educational reforms, transformation of schools into more inclusive places, reconsidering educational inclusion and a change of paradigm, which are essential to guide the study in the key of educational inclusion.

Expert validation: we selected a group of experts constituted by five faculty members related to the field of didactics, school organization and attention to diversity.

After the expert validation, we obtained the questions that would make up the final questionnaire, which were a total of 21. Although the number of surveyed teachers was small, this is justified, since the aim was to gather data that would allow us to prepare the questions of the interview and these had to be focused on aspects that were relevant for the teachers.

The surveyed teachers, 11 in total, participated in the study indirectly, although they do not represent the actual sample, since their opinions served as a basis to prepare the ultimate questions that would make up the interview.

Preparation of the interview: we selected the 12 questions that we believed were most relevant and gathered fundamental aspects for the study.

Table 2 shows the study sample, composed of 16 teachers from different levels of the education system. The population from which the sample derived belongs to the provinces of Seville and Badajoz (Spain). The participants were selected by convenience sampling and availability to participate in the study. The first two columns include the study cases and the type of centre to which they belonged. All the centres were public, with the exception of case 10, which was a charter school. The third column shows the speciality of the surveyed teachers.

Table 2: Study Sample

| Case | Type of centre | Teacher speciality |

|---|---|---|

| 1, 2, 3, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14 | Early Childhood and Primary Education School (ECPES) | Audition and language Second language: English Language and literature Primary Ed. tutor Early Ch. Ed. tutor Therapeutic Pedagogy Principal Head of studies |

| 4, 5 ,6, 7, 8, 13, 15, 16 | Secondary Education (SE) Baccalaureate (BAC) Training Modules (MOD) High school | Therapeutic pedagogy Social sciences Counselor Language and literature Physics and Chemistry Biology Foreign language: French Technical drawing Diversification |

Note: Developed by author.

Given the large amount of information gathered through the 16 interviews conducted, once these were transcribed, we had to make some decisions prior to the data analysis, thus we based the latter on major aspects of interest for the study. We organised the analysis into two levels. The first level includes the key aspects, whereas the second level gathers what could be considered as secondary aspects or those aspects that provide complementary information, thus resulting in a joint analysis. We followed the guidelines of Litosseliti (2003) for the analysis of the key questions, while the less relevant questions could be analysed at a different level or simply removed, since they are not considered essential for the analysis.

In our case, we did not remove any of the questions, although we grouped those that we thought were worth being analysed at a different level, as described in Table 3.

Table 3: Categorization levels of the interviews

| 1st level | 2nd level |

|---|---|

| Meaning of inclusive education Deficiencies of inclusive education | - |

| Involvement in inclusion | Educational inclusion and practice Disposition of centres |

| Teacher training | - |

| Actions of the centre | - |

| Students and inclusion | Inclusive education for everyone Educational inequalities |

| Educational inclusion and reformation | Re-structuring of centres Rethinking inclusion Change of paradigm |

| Improving the quality of inclusion | - |

Note: Developed by author.

Results, analysis and discussion

The obtained results of the categories of the analysis are organised into five figures. For the analysis and interpretation of the qualitative data, different categories and subcategories were selected among the proposals of quality indicators, considering the basic units of meaning. As a result of this process, a system of response categories was established, with their corresponding frequencies expressed in percentage data. We organised them based on the qualitative design combined with the descriptive quantitative approach, with the aim of delving into the analysis and considering, in addition, the contributions of the theoretical framework:

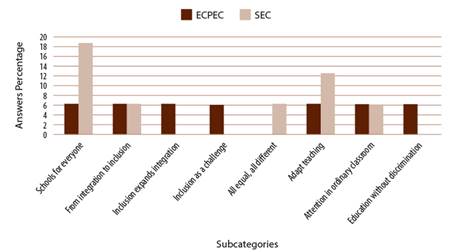

Figure 1 shows the answers of the participants regarding the meaning of inclusive education.

The obtained data demonstrate the need to create quality schools for all students, although the teachers from secondary education centres (SEC) insist on the need to initiate this process (18.75%), whereas those from early childhood and primary education centres (ECPEC) understand this process as a continuation (6.25%). In some cases, inclusion is understood as a synonymous of integration, whereas in other cases inclusion is an educational challenge for teachers, which also expands the process of integration (Casanova Rodríguez, 2011). Based on the acceptance of diversity, the aim is to adapt teaching to all the students in the classroom, where the educational treatment must be equal for everyone, considering individual differences within an educational framework without discrimination.

Figure 2 shows the answers of the participants about involvement in inclusion at the school and classroom levels.

Note: Developed by author.

Figure 2: Answers about involvement in inclusion at the school and classroom level

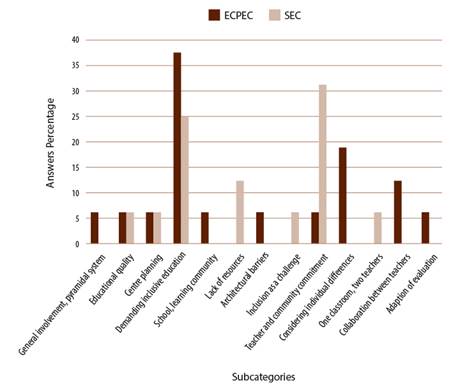

The participants understood that the involvement in inclusion must be general, and they conceived it as a pyramidal system in which everyone must contribute with the aim of improving the quality of education. As shown in Figure 3, this must be reflected in the planning of the centre, although 37.5% of the participants from ECPEC and 25% of those from SEC believed that their centres were not ready to respond to the demands of inclusive education, declaring: we are not prepared; all we use is palliative solutions (case 8). Some participants mentioned the lack of resources and others the need to remove architectural barriers.

Although the school is conceived as a learning community and inclusion is considered as a challenge for teachers (Azorín Abellán, 2018), according to the results shown in Figure 3, 31.25% of the teachers from secondary education centres pointed out the need to achieve a greater commitment from both teachers and the educational community. Regarding the teachers from ECPEC, 18.75% indicated the importance of considering individual differences in the classroom activities, whereas others spoke about collaboration between teachers, having two teachers in the classroom, and the need to adapt the evaluation to the students, as ways of committing to the practices derived from educational inclusion.

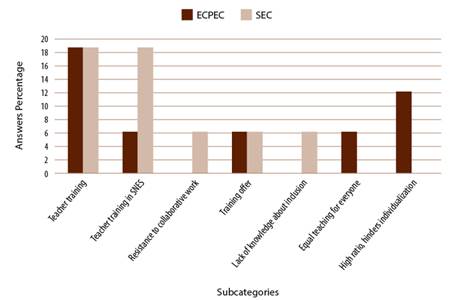

Next, Figure 3 shows the answers of the participants about teacher training.

The results show that 18.75% of the participants from all the educational levels considered that teachers are trained to attend to all students, with the exception of teachers from secondary education, who do not seem to be sufficiently prepared to attend to students with SENs, and the training they receive does not always respond to their needs, as they declared: they teach us how to write up an Individualised Curriculum Adaptation (ICA) rather than how to put it into practice (case 10). In other cases, teachers refuse to collaborate with other teachers, although researchers such as Krichesky and Murillo (2018) highlight the importance of collaboration between professionals. Regarding inclusion, there is a considerable lack of knowledge about its meaning and practical implications.

Although it is believed that the training given to teachers is adequate, it could be improved toward a “systemic” paradigm (Barrantes-Montero, 2015); however, some participants preferred to give the same teaching for all students, without considering the specific cases, since this is what they feel prepared for. However, the main difficulty in attending individual differences lies in the fact that the ratio is very high, which makes individualised attention more difficult, according to 12.25% of the teachers from ECPEC.

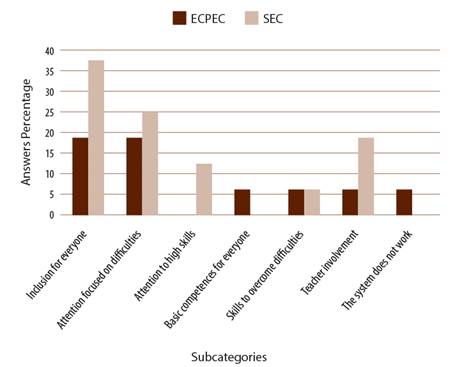

Figure 4 shows the answers of the participants about students regarding educational inclusion.

As can be observed, 18.75% of the teachers from ECPEC and 37.5% of those from SEC understood that inclusive education is intended for all students, whereas 18.75% of the participants from ECPEC and 25% of those from SEC stated that, in reality, inclusive education is focused on attending to students with more educational difficulties (González, 2011), and not all students.

Some participants pointed out the need to dedicate more attention to students with high capacities and others claimed that all students should reach the competences, although it is not always easy. This is demonstrated in the assertions of some teachers from SEC, as some of them stated: some students exclude themselves because they do not want to study, so this difference becomes an inequality (case 8).

The surveyed teachers agreed in asserting that educational attention should be more focused on the development of capacities than on analysing the difficulties of the students to deal with their learnings; they believed that it is necessary to achieve a greater commitment from the teachers in order to fulfill the objectives of inclusion, whereas only one teacher from ECPEC stated that the current education system does not work for any student. Next, Figure 5 shows the answers of the participants about educational inclusion and reformation.

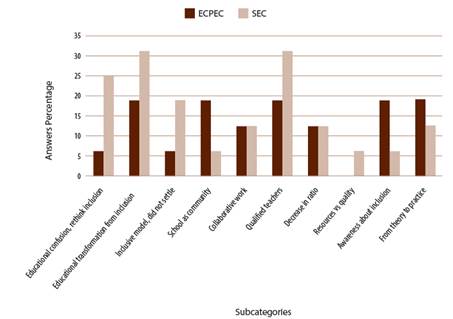

According to the data shown in Figure 5, 25% of the teachers from SEC claimed that there is a great confusion in the current educational scene, thus it would be convenient to rethink the argument of inclusive education, although 31.25% believed that the philosophy of inclusion could transform current education, a belief that is shared by 18.75% of the teachers from ECPEC.

Other participants, especially those from secondary education and baccalaureate, stated that the educational model has not settled yet in their centres: ...there is no awareness... this has not been assumed or assimilated yet (case 7). It is necessary to conceive the school as a learning community, in order to advance in the objectives of inclusive education, which requires a collaborative effort from teachers. This, in turn, would require guiding the training of teachers toward the objectives of inclusive education in the framework of efficient schools (Ainscow et al., 2012). The lack of teachers prepared to respond to these objectives was acknowledged by 18.75% of teachers from ECPEC and by 31.25% of those from SEC.

Other aspects of interest for teachers, which influence the functioning of inclusive education and are regarded as some of the current challenges, are the reduction of the ratio, the lack of resources in educational centres and, above all, the need to put the theory into practice (Casanova Rodríguez, 2011). These ideas were shared by 18.75% of the teachers from ECPEC and by 12.25% of those from SEC.

Conclusions

The analysis of the data allowed us to draw significant conclusions to guide teacher training in the key of educational inclusion, thus responding to the research objectives.

Inclusive education is not promoting a change of paradigm in current education; it is necessary to “open borders” (Azorín Abellán 2018), since it still remains in a process that does not seem to settle. There are breaches between the educational policies, practices and purposes of inclusive education. However, inclusion is promoting new ways of developing educational practices and understanding education, which are conceived as alternative to previous educational practices.

Despite the fact that, from the conceptual perspective, educational inclusion is intended for all students, and this is generally assumed by teachers, in reality it is perceived in the key of difficulty, since teachers usually think of students with special educational needs (SEN) when they mention inclusion. In this sense, the concept of SEN is associated to disability, without considering its implicit transient perspective. We can assert that the advance that should have been triggered by the change in research paradigm from integration to inclusion has not settled in practice.

Educational practices must be based on evidence, from which an educational response that adapts to the needs of the students must be designed. A relevant datum is that current education does not achieve the full development of capacities, since it is rather focused on attending to difficulties. Although teachers are well informed regarding the theory, in some cases they do not know how to put ideas into practice. Sarramona I López and Rodríguez Neira (2010) mentioned the effective and efficient work of educators alluding to autonomy as a demand of the very nature of pedagogical practice.

Current educational reforms do not come from the real needs of students, or those of the educational centres, although they have contributed to raising awareness in the educational community about the implications of attention to diversity for the school, which helps to promote the change and educational improvement in some centres. The contradictions of current educational policies are reflected in specific situations, such as the lack of guarantee for the continuity of the most vulnerable students and/or those at risk of educational and social exclusion, whose entry in the education system is facilitated, but their permanence is not assured.

The transformation of schools into more inclusive centres (Ainscow, 2012) requires the commitment of teachers to the philosophy of inclusion. Human and material resources are still considered key for the development of educational inclusion; the involvement of teachers with inclusion is fundamental and imperative, in some cases being even more important than resources. Sandoval Mena (2009) highlighted the inclusive values, such as collaboration, justice and equality, of future teachers to promote inclusion.

Transforming education is one of the most important challenges of our time, and one of the most effective strategies to achieve this is to empower and improve teachers (Hargreaves & Fullan, 2014). Current education requests teachers whose training is in line with the demands of a changing society, where diversity is a reality and social and educational inclusion is a principle. Teacher training must also avoid professional isolation and respond to the questions raised by diversity; a training in line with inclusion is necessary.

Next, we present the Quality Indicators that were determined based on the results and conclusions of this study, with the aim of guiding teacher training programs in the key of inclusion.

Inclusive educational model

Constant analysis of the educational reality in the framework of a changing and globalised society.

Educational model designed for the improvement of all students in the framework of inclusive schools.

Stronger association between educational theory and practice.

Inclusive institutional projects

Projects that consider educational responses to support diversity. Perceiving the school as a learning community.

Educational networks of schools as platforms for educational improvement.

Educational practices

Teaching practices based on evidence.

Design of innovative methodologies, based on an educational model in line with inclusion.

Educational research methodologies focused on the development of capacities.

Teacher training

Programs based on educational practices committed to inclusion. Programs that include the analysis of educational needs.

Programs focused on principles of comprehension, democracy and participation.

This proposal of quality indicators, to advance in the improvement of the quality of educational inclusion, involves open research lines on which further work needs to be done.