Introduction

Commonly known as heart urchins, the irregular echinoids of the order Spatangoida L. Agassiz, 1840 are represented in the fossil record since the lowermost Cretaceous (Berriasian, c. 145 Mya) and today are the most diverse group of extant echinoids (Villier, Néraudeau, Clavel, Neumann & David, 2004; Stockley, Smith, Littlewood, Lessios & Mackenzie-Dodds, 2005). Spatangoids are widely distributed throughout the ocean, from shallow waters to abyssal depths. Mostly spatangoids have evolved an infaunal lifestyle burrowing into the superficial layer of unconsolidated muddy and sandy sediments; however, some species living in the deep sea have adopted an epifaunal lifestyle (Mortensen, 1950; Mortensen,1951; Mironov, 1978). Owing to their ecological traits, heart urchins are considered important components of benthic communities. Spatangoids are deposit-feeders, they ingest a large amount of detritus from the sediment and cause bioturbation due to their locomotion and feeding mode (De Ridder, Jangoux & De Vos, 1987; Lohrer, Thrush, Hunt, Hancock & Lundquist, 2005). Concerning their reproductive aspects, spatangoids show broadcasting or brooding spawning modes, and indirect or direct developmental strategy, these life-history traits affects particularly the early larval dispersion and the distribution patterns of species (Poulin & Féral, 1996, Poulin & Féral, 1998).

The southwestern Atlantic Ocean (SWAO) receives waters formed in remotes areas of the world, generating one of the most energetic oceanic regions of the world (Piola & Matano, 2001). Along the Argentine continental shelf, the upper ocean is mainly dominated by the Malvinas Current, a branch of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current that flows offshore to north, the Brazil Current, a branch of the subtropical gyre that flows south along the continental slope of South America, and by the Brazil/Malvinas Confluence, the collision of these two opposite currents near 38° S latitude (Matano, Palma & Piola, 2010). Also, the deep layers from the continental slope off Argentina are characterized by a variety of water masses with origin in deep and bottom waters from the North Atlantic, South Pacific, and Antarctic regions (Piola & Matano, 2001). According with several authors, two biogeographic provinces are recognized on the Argentine continental shelf by the patterns of distribution of different macroinvertebrates taxa: the Argentine Biogeographic Province (ABP), and the Magellan Biogeographic Province (MBP) (Bernasconi, 1964; Bastida, Roux & Martínez, 1992; Doti, Roccatagliata & López Gappa, 2014). The ABP extends from 23° S (Cabo Frio, Brazil) to 43° S (Península Valdés, Argentina), while the MBP is present on both sides of South America, from the southeastern Pacific Ocean at 41° S (Puerto Montt, Chile) reaching around the tip of South America into the SWAO at 43° S latitude, where the MBP turns aside from shallow shelf waters following a northeastern direction to more deep shelf waters, as far as 35° S latitude (López Gappa, Alonso & Landoni, 2006; Doti et al., 2014).

Based on previous reports, there are eight spatangoids species present in the Argentine continental shelf and offshore: Abatus cavernosus (Philippi, 1845); Abatus philippiiLovén, 1871; Abatus agassiziiMortensen, 1910; Brisaster moseleyi (A. Agassiz, 1881); Tripylaster philippii (Gray, 1851); Tripylus excavatus (Philippi, 1845); Tripylus reductus (Koehler, 1912); and Delopatagus bruceiKoehler, 1907 (Bernasconi, 1964; Brogger et al., 2013; Fabri-Ruiz, Saucède, Danis & David, 2017; Saucède et al., 2020). D. brucei is considered due to its occurrence south off Tierra del Fuego (Saucède et al., 2020).

This paper aims to contribute to improving the knowledge of the diversity and distribution of the Spatangoida from the SWAO, through the study of specimens recently collected. Here we describe a new genus and species of Palaeotropidae from the Mar del Plata Canyon, which represents the first report for this family in Argentina. Besides, we inform new records in the SWAO for other known species.

Materials and methods

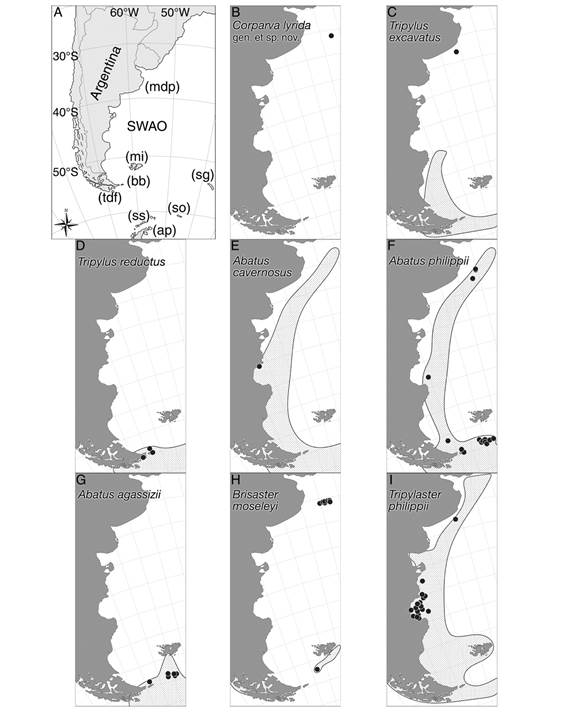

The study area is located at the southern extreme of the SWAO, from 37° to 55° S latitude at depths encompassing from the shallow waters of the continental shelf to abyssal waters of the slope off the Argentine coast (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1 Maps showing the studied area with the distribution of the species discussed in the present study. A. Positions for the main locations from the southwestern Atlantic Ocean discussed in this study. B. Corparva lyrida gen. et sp. nov. C. Tripylus excavatus. D. Tripylus reductus. E. Abatus cavernosus. F. Abatus philippii. G. Abatus agassizii. H. Brisaster moseleyi. I. Tripylaster philippii. B-I. species herein examined (marked signs) plotted on their previously registered distribution (dotted area). References: A. SWAO, southwestern Atlantic Ocean; mdp, Mar del Plata Canyon; mi, Malvinas Islands; bb, Marine Protected Area Namuncurá/Banco Burdwood; tdf, Tierra del Fuego; sg, South Georgia Islands; so, South Orkney Islands; ss, South Shetland Islands; and ap, Antarctic Peninsula.

The specimens were collected from several sites during eight cruises at different areas within the SWAO: continental shelf and slope off Buenos Aires, the Mar del Plata Canyon, San Jorge Gulf, Patagonian shelf, and the Marine Protected Area Namuncurá/Banco Burdwood (MPA-N/BB). These cruises were: “Mejillón II” (M II), 2009, 9-150 m depth, 3 sites; “Talud Continental I” (TC I), 2012, 200-3 006 m depth, 6 sites; “Talud Continental II” (TC II), 2013, 78-1 289 m depth, 2 sites; “Talud Continental III” (TC III), 2013, 1 310-3 447 m depth, 5 sites; “Área Marina Protegida Namuncurá/Banco Burdwood: Bentos” (AMP-N/BB-2016), 2016, 71-785 m depth, 16 sites; “PD BB ABR 17” (AMP-N/BB-2017), 2017, 48-646 m depth, 9 sites, “Pampa Azul Golfo San Jorge-BO/PD-GSJ-02-2017” (GSJ 2017), 2017, 36-106 m depth, 19 sites, and “AMP Namuncurá/Banco Burdwood: Ingenieros Ecosistémicos” (AMP-N/BB-2018), 2018, 78-694 m depth, 2 sites (Table 1). All cruises were performed on board of the R/V Puerto Deseado from CONICET.

Specimens were collected using an adapted towed dredge or a bottom trawl net. The towed dredge used consisted of a rigid body structure 150 cm long and 100 cm wide, with a 60 cm wide by 40 cm high mouth frame and carrying two joint fishing nets with two different pore-size (an external one of 3x3 cm, with another internal one of 1x1 cm).

Once onboard, specimens were fixed in 96 % ethanol. All the specimens are now housed in the National Invertebrate Collection of the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales “Bernardino Rivadavia” (MACN-In) from Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Gross morphology of specimens was studied under naked eye and using a stereomicroscope, while the ultrastructure of several appendages was analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Test measures were made with a digital caliper. To be able to reveal the arrangement of the plates, some specimens were carefully cleaned. Appendages and soft tissue were removed from the test with tweezers, and a small brush soaked with a diluted solution of sodium hypochlorite was used to remove the organic remains. When the plates and sutures were exposed and visible, the whole specimen was rinsed in distilled water. Plates were labelled according to the standard nomenclature for the test plating provided by Lovén (1874).

For SEM images, appendages (spines, pedicellariae, sphaeridia, and tube feet) were removed from different parts of the test and placed into distilled water. Organic remains were cleared with a diluted solution of sodium hypochlorite for a few minutes. The appendages were rinsed in distilled water twice, followed by a third rinse with 96 % ethanol to allow rapid air drying. Finally, appendages were transferred to aluminium stubs, sputtered with gold-palladium, and examined and photographed with a Philips XL30 scanning microscope at the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales “Bernardino Rivadavia” (MACN). Complete specimens were photographed using a Nikon D800 camera with a Micro-Nikkor 60 mm f/2.8 lens, and details of the plates from the test were photographed with a Zeiss Discovery V20 stereoscopic microscope.

This article is registered in ZooBank under ID: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:2FBDDA8F-DB8A-4266-B606-553AF5C2F366.

Results

In all, 299 specimens of spatangoids were collected and studied, identifying eight species distributed in two families, and six genera. In the present study, we report a new genus and species Corparva lyrida (Spatangoida: Palaetropidae) along with the occurrence and new records in the SWAO of known species.

In the Taxonomic List are listed the species identified following the classification of Kroh (2020) for higher-level taxa, Saucède et al. (2020) for the family Schizasteridae and its lower-level taxa, and Kroh & Mooi (2020) for the Palaeotropidae family.

Taxonomic List:

Phylum Echinodermata Bruguière, 1791

Class Echinoidea Leske, 1778

Order Spatangoida L. Agassiz, 1840

Suborder Paleopneustina Markov & Solovjev, 2001

Family Schizasteridae Lambert, 1905

Genus TripylusPhilippi, 1845

Tripylus excavatus (Philippi, 1845)

Tripylus reductus (Koehler, 1912)

Genus AbatusTroschel, 1851

Abatus cavernosus (Philippi, 1845)

Abatus philippiiLovén, 1871

Abatus agassiziiMortensen, 1910

Genus BrisasterGray, 1855

Brisaster moseleyi (A. Agassiz, 1881)

Genus TripylasterMortensen, 1907

Tripylaster philippii (Gray, 1851)

Suborder Brissidina Kroh & Smith, 2010 (= Brissidea of Stockley et al., 2005)

Family Palaeotropidae Lambert, 1896

Genus Corparva Flores, Penchaszadeh & Brogger gen. nov.

Corparva lyrida Flores, Penchaszadeh & Brogger sp. nov.

Systematics:

Order Spatangoida L. Agassiz, 1840

Suborder Brissidina Kroh & Smith, 2010

Family Palaeotropidae Lambert, 1896

Corparva Flores, Penchaszadeh & Brogger gen. nov.

Diagnosis: Test ovoid, small size, truncated posterior end. Semi-ethmolytic apical system, four gonopores. No frontal notch. Paired ambulacra apetaloid, pore-pairs small and rudimentary. Fascioles absent. Periproct on the posterior end, slightly inframarginal. Peristome D-shaped, sunken. Labrum narrow, not projecting over the peristome, reaching to rear part of second adjacent ambulacral plate. Plastron amphisternous, domed in profile. Primary spines slender, more abundant on aboral side, lacking on posterior ambulacral areas on oral side. Pedicellariae present: tridentate, globiferous, and triphyllous.

Type species: Corparva lyrida Flores, Penchaszadeh & Brogger sp. nov.

Etymology: Cor alluding for heart and parva for small (gender feminine).

ZooBank ID: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:13ACEDA6-DA67-414A-BBEE-9FB20288223F

Remarks: Corparva gen. nov. is included into the family Palaeotropidae Lambert, 1896 based on structural features as a thin ovate test, no frontal notch, paired ambulacra apetaloid, reduced peristome D-shaped, sternal plates symmetrical and fully tuberculate, episternal plates paired, and aboral surface with scattered small tubercles (Smith & Gale, 2009; Smith & Kroh, 2011). However, Corparva gen. nov. can be clearly separated from other genera of Palaeotropidae by possessing an apical system semi-ethmolytic, labral plate reaching to rear part of second adjacent ambulacral plate, and paired ambulacra deeply depressed forming rounded pouches (at least in females). We considered these features serve to distinguish our new species C. lyrida supporting the erection of a new genus.

As Néraudeau, David & Madon (1998) pointed out, the arrangement of the plates in the apical system should not be used as a morphological character to differentiate at family level, due to changes in the structure of the apical system occurred convergently in many different groups of spatangoids. Thus, we consider the semi-ethmolytic pattern of Corparva gen. nov. and the labral plate extending to the rear part of second adjacent ambulacral plate as features to separates it from the other genera of Palaeotropidae.

PalaeotropusLovén, 1874 differs by possessing an apical system monobasal with fused genital plates, anterior, two gonopores, paired ambulacra flush, uniserial ambulacral plates adapically, labral plate extending to rear of the first adjacent ambulacral plate, episternal plates strongly tapered to posterior, strong subanal heel, rounded subanal fasciole, row of larger tubercles and spines bordering the frontal ambulacrum, and ophicephalus pedicellariae present (Lóven, 1871; Lóven, 1874; Mortensen, 1950; Mironov, 2006; Kroh & Mooi, 2020).

Palaeobrissus A. Agassiz, 1883 differs by its ethmolytic apical system with fused genital plates, anterior, two gonopores in the posterior genital plates surrounded by a rim and sometimes two smaller anterior gonopores in large specimens, paired ambulacra flush, subpetaloid with ambulacral pores double, peristome not sunken and transversally oval, labral plate extending to first adjacent ambulacral plate, slightly projecting over peristome, and rounded subanal fasciole present in juveniles (lost in adults) (Agassiz, 1883; Mortensen; 1950; Kroh & Mooi, 2020).

PaleotremaKoehler, 1914 differs by having a test elongated, posterior end obliquely truncated, monobasal apical system with fused genital plates, anterior, three gonopores, paired ambulacra flush, labral plate extending to first adjacent ambulacral plate, episternal plates strongly tapered to posterior, plastron forming keel posteriorly, rounded subanal fasciole, row of larger tubercles and spines bordering the frontal ambulacrum, ophicephalus pedicellariae present and globiferous absent (Agassiz, 1879; Koehler, 1914; Mortensen, 1950; Kroh & Mooi, 2020).

ScrippsechinusAllison, Durham & Mintz, 1967 differs by possessing ethmolytic apical system with fused genital plates, subcentral, paired ambulacra flush, uniserial ambulacral plates adapically, labral plate not extending beyond first adjacent ambulacral plate, projecting over peristome, and globiferous pedicellariae absent (Allison, Durham & Mintz, 1967; Kroh & Mooi, 2020).

KermabrissoidesBaker, 1998 differs by its ethmolytic apical system, subcentral, gonopores on top of small cones, paired ambulacra flush, subpetaloid, labral plate extending to third adjacent ambulacral plate, rounded subanal fasciole with 2-3 tube feet either side, ophicephalus pedicellariae present and globiferous absent (Baker & Rowe, 1990; Baker, 1998; Kroh & Mooi, 2020).

Corparva lyrida

Flores, Penchaszadeh & Brogger sp. nov.

Diagnosis: As for the genus.

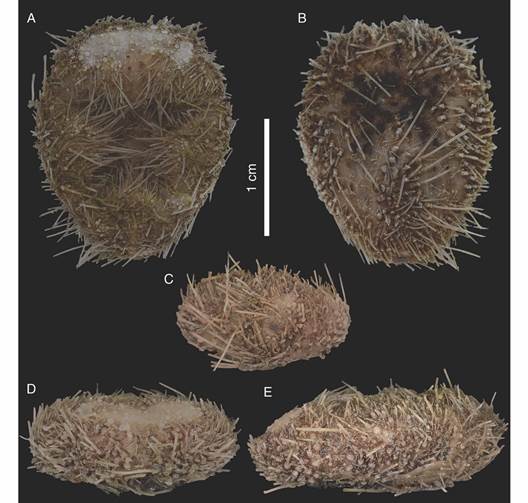

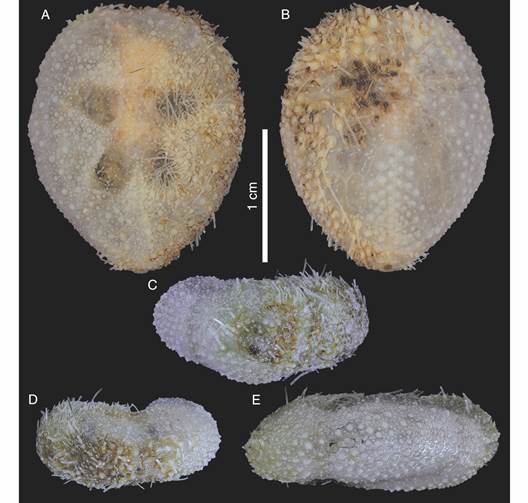

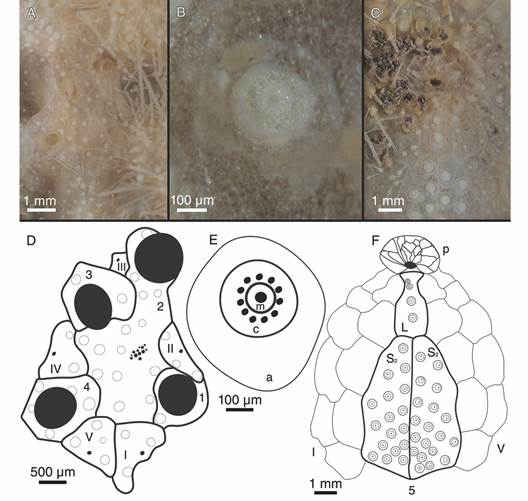

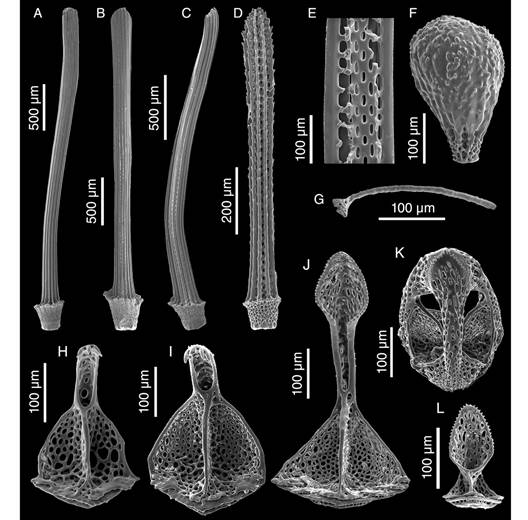

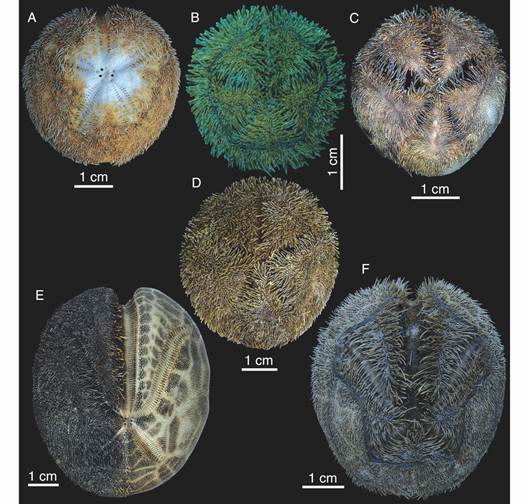

Description: Test fragile, low in profile, oval in outline with truncated posterior end, anterior part wider than posterior part, rounded at ambital edge, wedge-shaped in lateral profile (Fig. 2A, Fig. 2B, Fig. 2C, Fig. 2D, Fig. 2E, Fig. 3A, Fig. 3B, Fig. 3C, Fig. 3D, Fig. 3E). Small test size, 18.2 mm long, 14.8 mm wide, and 6.0 mm high. Fascioles absent (Fig. 2A, Fig. 2B, Fig. 2C, Fig. 2D, Fig. 2E, Fig. 3A, Fig. 3B, Fig. 3C, Fig. 3D, Fig. 3E). Apical system central, sunken with respect to adjacent interambulacral areas, semi-ethmolytic, with four genital pores of same size opening on inner part of genitals (Fig. 2A, Fig. 3A, Fig. 4A, Fig. 4D). Madreporic plate (G2) enlarged posteriorly between genitals 1 and 4 but not separating oculars V from I, hydropores scarce (Fig. 4D). Frontal notch absent, ambulacrum III flush with test (Fig. 2A, Fig. 2D, Fig. 3A, Fig. 3D). Non-petaloid paired ambulacra, cruciform, deeply depressed forming rounded pouches (Fig 3A), double row of ambulacral plates adapically. Ambulacral tube feet simple on aboral side, pore-pairs small and rudimentary, there are no occluded plates at the end of the paired ambulacra, posterior paired ambulacra slightly shorter than anterior. Paired ambulacra pouches reaching fifth ambulacral plate (from apex to ambitus) in ambulacrum IV and V, tuberculation on these plates scarce. Plates from ambulacra II and IV remain parallel-sided on oral side (Fig 3B). Peristome D-shaped, sunken, situated between 25-34% of test length from anterior edge, upper peristome portion occupied by many plates of different sizes, becoming smaller surrounding mouth (Fig. 3B, Fig. 4C, Fig. 4F). Phyllodes reaching fourth plate in paired ambulacra. Penicillate tube feet conspicuous (Fig. 2B, Fig. 3B), terminating in well-developed disc with finger-like projections, each supported by a skeletal rod (Fig. 5G). Interambulacrum 5 continuous, posterior part forming slightly keel (Fig. 2E, Fig. 3E). Labral plate not projecting over peristome, narrow, in contact with both sternal plates, extending to rear part of second adjacent ambulacral plate (Fig. 4C, Fig. 4F). Plastron amphisternous (Fig. 4F). Sternal plates symmetrical, slightly bowed, extending to fifth adjacent ambulacral plate, posterior suture of plate 5.b.2 coincides with fifth plate in ambulacrum I (Fig. 4F). Episternal plates paired and opposite. Basicoronal plate amphiplacous in interambulacrum 4. Periproct circular, located on posterior vertical end, inframarginal, visible from oral side, covered by plates of variable sizes and shapes, larger plates close to external edge and smaller plates towards center (Fig. 2B, Fig. 2C, Fig. 3B, Fig. 3C). Distinct subanal tube feet absent. Primary tubercles numerous and uniformly spaced on aboral surface and absent on ambulacral areas on oral side up to fifth plate in ambulacrum V and fourth plate in ambulacrum I (Fig. 2B, Fig. 3B), mamelon well-developed with central perforation and slightly crenulated base, areole well-developed (Fig. 4B, Fig. 4E). Secondary tubercles smaller, with same general shape as primary ones, with mamelon usually reduced. Spines scattered on oral side of ambulacra I and V, but uniformly distributed in sternal plates, ambital region, and apical side (Fig. 2A, Fig. 2B). Primary spines shorter, straight, with pointed tip, and shaft with longitudinal and ornamented striations (Fig. 5D). Longest primary spines found on plastron. They are large, curved and spatulate towards distal end, with well-developed acetabulum and base, poorly developed milled ring, and shaft with longitudinal smooth striations (Fig. 5A, Fig. 5B, Fig. 5C). Spine cylinder with helicoidal pore arrangement (Fig. 5E). Globiferous, tridentate, and triphyllous pedicellariae (Fig. 5H, Fig. 5I, Fig. 5J, Fig. 5K, Fig. 5L). Globiferous pedicellariae more frequently found on apical side, head and stalk embedded in a yellowish tissue, three-valved, valves whit large and wide base, blade forms a curved semi-tube terminating in 3-6 sharp and tiny hooks (Fig. 5H, Fig. 5I). Tridentate pedicellariae on apical and oral side, three-valved, shovel-shaped valves with widen and finely serrated distal part separated from triangular base by elongated, narrow, and straight tubular part (Fig. 5J, Fig. 5K). Triphyllous pedicellariae smallest, with minute base, and large and wide blade with finely serrated edge (Fig. 5L). Sphaeridiae swollen in shape, irregularly rugose (Fig. 5F), on short stalks, numerous along posterior ambulacral areas on oral side. Test colour brown-brownish with whitish spines in ethanol; denuded test white.

Fig. 2 Corparva lyrida gen. et sp. nov. (Holotype MACN-In 43280), complete specimen. A. Aboral view. B. Oral view. C. Posterior view. D. Anterior view. E. Side view (anterior to the left).

Fig. 3 Corparva lyrida gen. et sp. nov. (Holotype MACN-In 43280), specimen partially cleaned. A. Aboral view. B. Oral view. C. Posterior view. D. Anterior view. E. Side view (anterior to the left).

Fig. 4 Morphological details and drawings of Corparva lyrida gen. et sp. nov. A. Apical system. B. Primary tubercle. C. Peristome. D. Hemilytic (semi-ethmolytic) apical system plating drawing. E. Primary tubercle diagram. F. Peristome and plastron plating drawing. References: D. 1-4 genital plates (2 also madreporite), and I-V ocular plates; E. a areole, c crenulated platform, and m perforated mamelon; and F. p peristome, L labrum, S 2 sternal plates, I and V ambulacra, and 5 posterior interambulacrum.

Fig. 5 SEM images of appendages of Corparva lyrida gen. et sp. nov. A-C. Primary spines from the plastron. D. Ambulacrum spine from the oral side. E. View of the inner cylinder of a primary spine. F. Spheridium. G. Skeletal rod from an oral penicillate podium. H-I. Valve of globiferous pedicellaria with three and four terminal teeth, respectively. J. Valve of a tridentate pedicellaria. K. Tridentate pedicellaria. L. Valve of a triphyllous pedicellaria.

Etymology: lyrida refers to the April Lyrids, the meteor shower that occurs each year in the constellation Lyra. The specific name is a noun in apposition (feminine).

Examined material: Holotype MACN-In 43280 (one half denuded specimen in ethanol 70 %, and external appendages mounted on three SEM stubs) (Table 1).

TABLE 1 Collection data of the specimens studied

| MACN-In | Expedition - Station - Site | Lat. (S) | Long. (W) | Depth (m) | Date (yy-mm-dd) | Spms. | Fishing gear |

| 43269 | M II - 7 | 38°46’34” | 55°50’38” | 92 | 2009-09-11 | 1 | towed dredge |

| 43270 | M II - 10 | 39°05’49” | 58°02’09” | 74 | 2009-09-12 | 3 | towed dredge |

| 43271 | M II - 11 | 39°01’23” | 58°10’02” | 55 | 2009-09-12 | 3 | towed dredge |

| 43272 | TC I - 2 | 37°57’11” | 55°11’03” | 291 | 2012-08-10 | 1 | towed dredge |

| 43273 | TC I - 3 | 37°59’39” | 55°13’03” | 250 | 2012-08-10 | 16 | bottom trawl net |

| 43274 | TC I - 5 | 37°58’39” | 55°09’06” | 528 | 2012-08-10 | 1 | bottom traw1 net |

| 43275 | TC I - 14 | 38°00’59” | 54°30’19” | 1 006 | 2012-08-11 | 2 | bottom trawl net |

| 43276 | TC I - 32 | 37°59’48” | 55°12’29” | 319 | 2012-08-17 | 1 | towed dredge |

| 43277 | TC I - 33 | 37°58’42” | 55°11’54” | 308 | 2012-08-17 | 2 | bottom trawl net |

| 43278 | TC II - 43 | 37°53’50” | 54°30’27’’ | 998 | 2013-05-26 | 1 | bottom traw1 net |

| 43279 | TC II - 44 | 37°53’33” | 54°42’56” | 780 | 2013-05-26 | 3 | bottom trawl net |

| 43280 | TC III - 47 | 38°06’34” | 53°42’50” | 2 950 | 2013-09-06 | 1 | bottom trawl net |

| 43281 | TC III - 51 | 38°01’23” | 53°51’00” | 2 212 | 2013-09-07 | 1 | bottom traw1 net |

| 43282 | TC III - 53 | 37°52’37” | 53°54’15” | 1 763 | 2013-09-08 | 12 | bottom trawl net |

| 43283 | TC III - 55 | 37°52’09” | 53°51’35” | 1 712 | 2013-09-08 | 9 | bottom trawl net |

| 43284 | TC III - 59 | 37°49’41” | 54°5’14” | 1 398 | 2013-09-10 | 1 | bottom trawl net |

| 43285 | AMP-N/BB-2016 - 5 - 126 | 55°02’17” | 65°46’07’’ | 118 | 2016-04-06 | 1 | towed dredge |

| 43286 | AMP-N/BB-2016 - 5 - 127 | 55°02’15” | 65°48’24” | 114 | 2016-04-06 | 1 | bottom traw1 net |

| 43287 | AMP-N/BB-2016 - 11 - 338 | 54°30’06” | 64°12’06” | 107 | 2016-04-22 | 1 | bottom trawl net |

| 43288 | AMP-N/BB-2016 - 23 - 226 | 54°45’34” | 59°52’08” | 182 | 2016-04-13 | 1 | bottom trawl net |

| 43289 | AMP-N/BB-2016 - 26 - 24 | 54°24’13” | 58°28’17” | 135 | 2016-03-29 | 1 | towed dredge |

| 43290 | AMP-N/BB-2016 - 26 - 27 | 54°24’57” | 58°30’55” | 137 | 2016-03-29 | 1 | bottom trawl net |

| 43291 | AMP-N/BB-2016 - 28 - 50 | 54°28’50” | 59°11’40” | 122 | 2016-03-30 | 1 | towed dredge |

| 43292 | AMP-N/BB-2016 - 30 - 185 | 54°16’40” | 59°57’47” | 96 | 2016-04-10 | 1 | towed dredge |

| 43293 | AMP-N/BB-2016 - 31 - 197 | 54°29’58” | 59°51’32” | 109 | 2016-04-10 | 3 | bottom trawl net |

| 43294 | AMP-N/BB-2016 - 32 - 77 | 54°32’36” | 60°01’17” | 98 | 2016-03-30 | 1 | bottom traw1 net |

| 43295 | AMP-N/BB-2016 - 33 - 159 | 54°25’46” | 60°38’52” | 101 | 2016-04-08 | 5 | bottom trawl net |

| 43296 | AMP-N/BB-2016 - 34 - 156 | 54°27’15” | 60°58’49” | 100 | 2016-04-07 | 15 | bottom trawl net |

| 43297 | AMP-N/BB-2016 - 39 - 141 | 54°50’41” | 63°59’54” | 183 | 2016-04-06 | 1 | bottom traw1 net |

| 43298 | AMP-N/BB-2016 - 39 - 141 | 54°50’41” | 63°59’54” | 183 | 2016-04-06 | 2 | bottom trawl net |

| 43299 | AMP-N/BB-2016 - 41 - 350 | 54°19’55” | 64°14’15” | 122 | 2016-04-22 | 1 | bottom trawl net |

| 43300 | AMP-N/BB-2016 - 41 - 350 | 54°19’55” | 64°14’15” | 122 | 2016-04-22 | 5 | bottom trawl net |

| 43301 | AMP-N/BB-2017 - 5- 10 | 53°07’41” | 65°47’08” | 294 | 2017-04-23 | 2 | towed dredge |

| 43302 | AMP-N/BB-2017 - 9 - 49 | 54°52’34” | 64°17’46” | 146 | 2017-04-24 | 1 | towed dredge |

| 43303 | AMP-N/BB-2017 - 23 - 173 | 54°26’06” | 59°30’15” | 91 | 2017-05-01 | 1 | bottom trawl net |

| 43304 | AMP-N/BB-2017 - 24 - 184 | 54°19’57” | 59°53’45” | 97 | 2017-05-01 | 1 | bottom traw1 net |

| 43305 | AMP-N/BB-2017 - 25 - 304 | 54°20’46” | 60°20’46” | 104 | 2017-05-09 | 1 | bottom trawl net |

| 43306 | AMP-N/BB-2017 - 27 - 326 | 54°06’27” | 60°52’46” | 128 | 2017-05-09 | 1 | bottom trawl net |

| 43307 | AMP-N/BB-2017 - 27 - 326 | 54°06’27” | 60°52’46” | 128 | 2017-05-09 | 1 | bottom trawl net |

| 43308 | AMP-N/BB-2017 - 27 - 327 | 54°06’27” | 60°52’46” | 132 | 2017-05-09 | 2 | towed dredge |

| 43309 | AMP-N/BB-2017 - 31 - 269 | 53°40’21” | 61°38’15” | 642 | 2017-05-07 | 38 | bottom traw1 net |

| 43310 | GSJ 2017 - 3 - ID 55 | 43°43’12” | 64°31’48” | 65 | 2017-10-29 | 1 | bottom trawl net |

| 43311 | GSJ 2017 - 11 - ID 42 | 44°53’24” | 65°08’24” | 84 | 2017-10-31 | 4 | bottom trawl net |

| 43312 | GSJ 2017 -12 - ID 41 | 45°08’24” | 64°50’60” | 83 | 2017-10-31 | 1 | bottom traw1 net |

| 43313 | GSJ 2017 - 13 - ID 39 | 45°14’24” | 65°09’00” | 91 | 2017-10-31 | 1 | bottom trawl net |

| 43314 | GSJ 2017 - 17 - ID 36 | 45°13’12 “ | 66°13’48” | 78 | 2017-11-01 | 1 | bottom trawl net |

| 43315 | GSJ 2017 - 23 - ID 32 | 45°34’48” | 66°11’24” | 94 | 2017-11-02 | 38 | bottom trawl net |

| 43316 | GSJ 2017 - 24 - ID 31 | 45°32’24” | 65°48 ‘36” | 98 | 2017-11-02 | 2 | bottom trawl net |

| 43317 | GSJ 2017 - 26 - ID 29 | 45°34’48” | 66°07’48” | 83 | 2017-11-02 | 1 | bottom traw1 net |

| 43318 | GSJ 2017 - 29 - ID 26 | 45°55’12” | 65°50’24” | 99 | 2017-11-03 | 1 | bottom trawl net |

| 43319 | GSJ 2017 - 31 - ID 24 | 45°53’60” | 66°35’24” | 96 | 2017-11-03 | 47 | bottom traw1 net |

| 43320 | GSJ 2017 - 33 - ID 22 | 45°54’36” | 67°18’36” | 72 | 2017-11-03 | 1 | bottom trawl net |

| 43321 | GSJ 2017 - 37 - ID 19 | 46°13’48” | 66°33’36” | 99 | 2017-11-04 | 4 | bottom trawl net |

| 43322 | GSJ 2017 - 39 - ID 17 | 46°14’24” | 65°49’12” | 98 | 2017-11-04 | 26 | bottom trawl net |

| 43323 | GSJ 2017 - 42 - ID 14 | 46°34’48” | 65°08’24” | 106 | 2017-11-05 | 1 | bottom trawl net |

| 43324 | GSJ 2017 - 42 - ID 14 | 46°34’48” | 65°08’24” | 106 | 2017-11-05 | 1 | bottom traw1 net |

| 43325 | GSJ 2017 - 54 - ID 68 | 46°54’36” | 66°42’36” | 57 | 2017-11-06 | 1 | bottom trawl net |

| 43326 | GSJ 2017 - 55 - ID 69 | 46°45’36” | 66°54’36” | 74 | 2017-11-07 | 1 | bottom trawl net |

| 43327 | GSJ 2017 - 56 - ID 8 | 46°32’24” | 67°19’48” | 74 | 2017-11-07 | 5 | bottom traw1 net |

| 43328 | GSJ 2017 - 59 - ID 10 | 46°33’36” | 66°36’36” | 95 | 2017-11-07 | 11 | bottom trawl net |

| 43329 | AMP-N/BB-2018 - 1 - 157 | 54°53’00” | 67°48’36” | 140 | 2018-09-01 | 3 | bottom trawl net |

| 43330 | AMP-N/BB-2018 - 25- 120 | 54°30’48” | 60°25’35” | 100 | 2018-08-28 | 1 | bottom trawl net |

References: M II “Mejillon II” expedition; TC I “Talud Continental I” expedition; TC II “Talud Continental II” expedition; TC III “Talud Continental III” expedition; AMP-N/BB-2016 “Area Marina Protegida Namuncurá - Banco Burdwood” expedition; AMP-N/BB-2017 “PD BB ABR 17” expedition; AMP-N/BB-2018 “AMP Namuncurá/Banco Burdwood: Ingenieros Ecosistémicos” expedition; GSJ 2017 “Pampa Azul Golfo San Jorge-BO/PD-GSJ-02-2017” expedition; and Spms. number of specimens.

Type locality: Mar del Plata Canyon (38°06’34’’ S & 53°42’50’’ W), Argentine continental slope (Fig. 1B).

Depth: 2 950 m.

Distribution: Only know from the type locality (Fig. 1B).

Zoobank ID: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:9B936F7D-860D-4138-A991-673821C3AF48

Remarks: C. lyrida sp. nov. is based on a single complete specimen (holotype MACN-In 43280). Its test is fragile and small (18.2 mm long, 14.8 mm wide, and 6.0 mm high), despite this we consider that the specimen studied is an adult, due to the presence of open gonopores. Of course, this supposition is not conclusive but it is in accordance with the characteristic small form of adult specimens among the family Palaeotropidae (Lovén 1871; Koehler, 1914; Mortensen, 1950; Allison, Duncan & Mintz, 1967; Baker & Rowe, 1990; Mironov, 2006). Mortensen (1950) report the presence of mature gonads containing a few ripe eggs in a specimen of Palaeotropus josephinae of 14 mm length.

In some spatangoids, fascioles may be present during all stage of development, in others they are present in juveniles and then maybe secondarily lost in adults, and in some taxa there is no evidence that fascioles were developed during ontogeny (Smith & Stockley, 2005; Stockley et al., 2005). Due to the holotype of C. lyrida sp. nov. does not present any trace of fascioles, and it is the only specimen that we have, we assumed that fascioles are absent at least in adults. Additional specimens in different stages of development are needed to test if fascioles develop during ontogeny or it is completely lost in C. lyrida sp. nov.

Corparva lyrida sp. nov. shows various secondary morphological simplifications that suggest an epibenthic lifestyle. As is observed in many others deep-sea spatangoids (Larrain, 1985; Stockley et al. 2005; Saitoh & Kanazawa, 2012), C. lyrida sp. nov. has features related with the building and maintenance of sanitary funnels poorly developed (absence of fascioles and distinctive tufts of spines on the aboral side or at the posterior end of the test, and the inframarginal position of the anus). Besides, others ecological traits present in deep-sea taxa and C. lyrida are the test thinner than shallow waters spatangoids, and the poorly developed (or completely lost in some groups) of petals and specialized tube feet, due to in the deep-sea the respiratory demanding is less than in shallow waters (Stockley et al., 2005).

Family Schizasteridae Lambert, 1905

Genus TripylusPhilippi, 1845

Tripylus excavatus (Philippi, 1845)

(Fig. 6A)

Examined material: MACN-In 43270 (Table 1).

Distribution: Tripylus excavatus occurs northward in the SWAO at 39° S (this study), and southward occurs along the Strait of Magellan, Tierra del Fuego, Isla de los Estados, and Cape Horn (Fig. 1C) (Fabri-Ruiz et al., 2017). Also recorded at South Georgia Islands (Saucède et al., 2020).

Depth: From the littoral to 110 m depth (Saucède et al., 2020).

Fig. 6 Images of specimens discussed in the present study. A. Aboral view of Tripylus excavatus (Philippi, 1845) (MACN-In 43270, specimen partially cleaned). B. Aboral view of Abatus cavernosus (Philippi, 1845) (MACN-In 43314). C. Aboral view of Abatus philippiiLovén, 1871 (MACN-In 43273). D. Aboral view of Abatus agassiziiMortensen, 1910 (MACN-In 43304). E. Aboral view of Brisaster moseleyi (A. Agassiz, 1881) (MACN-In 43309), specimen partially cleaned). F. Aboral view of Tripylaster philippii (Gray, 1851) (MACN-In 43316).

Remarks: Here we report the northernmost record for T. excavatus at 39°05’49’’ S & 58°02’09’’ W at 74 m depth (Table 1, Fig. 1C), resulting in a great extension in its range of distribution. Despite its broad wide range, T. excavatus seems to be an unusual species. Among 299 spatangoids collected we found only three specimens, this peculiarity also was highlighted by Bernasconi (1953), Bernasconi (1966). In this line, is to be expected that the disjunct distribution shown in figure 1C became continuous as the sampling increasing in both effort and quality for this area.

Tripylus reductus (Koehler, 1912)

Examined material: MACN-In 43285, MACN-In 43286, MACN-In 43297, MACN-In 43299 (Table 1).

Distribution: T. reductus is restricted to the southern region of the SWAO (Tierra del Fuego, Isla de los Estados) (Fig. 1D), and the northern part of the Antarctic Peninsula, also South Shetland Islands, and South Orkney Islands (Saucède et al., 2020).

Depth: From 50 to 761 m depth (Saucède et al., 2020).

Tripylus sp.

Examined material: MACN-In 43302 (Table 1).

Distribution: Isla de los Estados.

Depth: 146 m.

Remarks: Test fragment identified at the generic level due to the lack of diagnostic characters.

Genus AbatusTroschel, 1851

Abatus cavernosus (Philippi, 1845)

(Fig. 6B)

Examined material: MACN-In 43314 (Table 1).

Distribution: Wide distribution along the SWAO from 35° S to 55° S, including the Straits of Magellan, and Malvinas Islands (Fig. 1E) (Brogger et al., 2013). Also, along the Antarctic Peninsula, South Orkney Islands, South Georgia Islands, South Shetland Islands, and Bouvet Islands (David, Saucède, Chenuil, Steimetz & De Ridder, 2016; Saucède et al., 2020).

Depth: From 10 to 1 000 m depth (Saucède et al., 2020). Abatus cavernosus is commonly found in shallow waters southward of 44° S, while northward off Buenos Aires it occurs from 100 to 1 000 m depth (Brogger et al., 2013; Saucède et al., 2020).

Abatus philippiiLovén, 1871

(Fig. 6C)

Examined material: MACN-In 43269, MACN-In 43272, MACN-In 43273, MACN-In 43276, MACN-In 43277, MACN-In 43287, MACN-In 43288, MACN-In 43290, MACN-In 43291, MACN-In 43292, MACN-In 43294, MACN-In 43295, MACN-In 43298, MACN-In 43301, MACN-In 43305, MACN-In 43306, MACN-In 43308, MACN-In 43323 (Table 1).

Distribution: Widely distributed along the SWAO from 35° S to 55° S, including the Strait of Magellan, Isla de los Estados, Malvinas Islands (Bernasconi, 1964; Bernasconi,1966; Fabri-Ruiz et al., 2017), and the MPA-N/BB (this study). In the southeastern Pacific Ocean at 52° S latitude. In the Southern Ocean recorded at South Georgia Islands, South Shetland Islands, South Orkney Island, Sabrina Coast, and Ross Sea (Saucède et al., 2020).

Depth: From 25 to 800 m depth (Saucède et al., 2020).

Remarks: Here we report the first record for A. philippi at the MPA-N/BB (Table 1). Due to the occurrence of the species in surrounding areas, its presence in the AMP-N/BB was expected (Fig. 1F).

Abatus agassiziiMortensen, 1910

(Fig. 6D)

Examined material: MACN-In 43293, MACN-In 43296, MACN-In 43300, MACN-In 43303, MACN-In 43304, MACN-In 43307 (Table 1).

Distribution: A. agassizii occurs in the southern region of the SWAO, including Tierra del Fuego, Isla de los Estados, Malvinas Islands (Bernasconi, 1964; Saucéde et al., 2020), and the AMP-N/BB (this study) (Fig. 1G). Also recorded in the Southern Ocean at South Georgia Islands, South Shetland Island, the northern end of the Antarctic Peninsula, and in the eastern Weddell Sea (Saucède et al., 2020).

Depth: From the littoral to 600 m depth (Saucède et al., 2020).

Remarks: Here we report the first record for A. agassizii at the MPA-N/BB (Table). The range of distribution known for A. agassizii seems to have a north limit at Malvinas Islands. These new records for the AMP-N/BB are in accord with the distribution area known for the species (Fig. 1G).

Abatus sp.

Examined material: MACN-In 43289, MACN-In 43330 (Table 1).

Distribution: MPA-N/BB.

Depth: MACN-In 43289 at 135 m depth, and MACN-In 43330 at 100 m depth

Remarks: Two test fragments identified at the generic level due to the lack of diagnostic characters.

Genus BrisasterGray, 1855

Brisaster moseleyi (A. Agassiz, 1881)

(Fig. 6E)

Examined material: MACN-In 43274, MACN-In 43275, MACN-In 43278, MACN-In 43279, MACN-In 43281, MACN-In 43282, MACN-In 43283, MACN-In 43284, MACN-In 43309 (Table 1).

Distribution: B. moseleyi is recorded on both side of South America, in the southeastern Pacific Ocean off Chile from 45° S to 54° S, the Straits of Magellan, and in the SWAO recorded at Malvinas Islands (Saucède et al., 2020). We report the first record of B. moseleyi at both the northwest slope surrounding the MPA-N/BB, and the Mar del Plata Canyon (Fig. 1H). In the Southern Ocean recorded at South Orkney Islands (Saucède et al., 2020).

Depth: From 400 m (Saucède et al., 2020) to 2 212 m depth (this study) (Table 1).

Remarks: According to Saucède et al. (2020) the known geographic and bathymetric limit for B. moseleyi was the Malvinas (Falkland) Islands in the SWAO and 1 400 m depth, respectively. Here we report the northernmost, as well as the deepest distribution for B. moseleyi so far known. The former is the Mar del Plata Canyon on the Argentine continental slope (38°01’23’’ S & 53°51’00’’ W), and the second 2 212 m depth (MACN-In 43281) (Table 1). In addition, we report its occurrence at the northwest slope of the MPA-N/BB at 642 m depth (MACN-In 43309) (Fig. 1H). While B. moseleyi is a typical deep-sea species, it should be mentioned that also was found in the shallow waters from the Strait of Magellan by Larraín et al. (1999). Thus, the records here presented confirm for the first time the presence of B. moseleyi in deep waters off Argentina, an extraordinary extension to its geographic and bathymetric range.

Hood and Mooi (1998) pointed out that examined specimens labelled as B. moseleyi from Chile (southeastern Pacific Ocean) were distinct from other B. moseleyi from the Malvinas Islands and Patagonia (SWAO) and considered them as two distinct taxa termed “B. moseleyi (north)” and “B. moseleyi (south)” respectively. Also, their phylogenetic analysis based in morphological characters revealed that B. moseleyi (north) is more closely related to those species of Brisaster from the west coast of the Americas, while B. moseleyi (south) is a sister taxon of B. antarcticus (Döderlein, 1906). Brisaster moseleyi (south) and B. antarcticus differ from B. moseleyi (north) by possessing narrow petals IV and V, and long and narrow plastron (Hood & Mooi, 1998), these features were also present in the specimens treated in this study (Fig. 6E). Besides, following the identification key provided by Saucède et al. (2020) the specimens collected match well with their B. moseleyi entity, differing from B. antarcticus by having the apical system slightly displaced posteriorly, and the posterior petals short, slightly more than 1/3 the length of the anterior paired petals (Fig. 6E). Due to the uncertainty in taxonomic distinctiveness and to avoid possible futures nomenclature troubles, the specimens treated in this study are provisionally assigned to B. moseleyi. Genetic studies could help reveal the specific validation of the north/south groups and possible synonyms, enriched through the inclusion of samples from the northernmost population of B. moseleyi found at the Mar del Plata Canyon on the Argentine continental slope SWAO, and to reconstruct phylogenetic relationships among Brisaster species.

Genus TripylasterMortensen, 1907

Tripylaster philippii (Gray, 1851)

(Fig. 6F)

Examined material: MACN-In 43271, MACN-In 43310, MACN-In 43311, MACN-In 43312, MACN-In 43313, MACN-In 43315, MACN-In 43316, MACN-In 43317, MACN-In 43318, MACN-In 43319, MACN-In 43320, MACN-In 43321, MACN-In 43322, MACN-In 43324, MACN-In 43325, MACN-In 43326, MACN-In 43327, MACN-In 43328, MACN-In 43329 (Table 1).

Distribution: T. philippii occurs at the SWAO from 35° S up to the southeastern Pacific Ocean at 41° S, including the Strait of Magellan, Tierra del Fuego, Isla de los Estados, and Malvinas Islands (Fig. 1I) (Bernasconi, 1964; Fabri-Ruiz et al., 2017). Also recorded at the South Georgia Islands, and close to Prince Edward Island (Saucède et al., 2020).

Depth: From the littoral to 600 m depth (Saucède et al., 2020).

Discussion

The family Palaeotropidae comprises six genera including the new genus here described. Comparing structural features and shape of the test, development of petals, the shape of peristome, and aboral tuberculation, Corparva gen. nov. conform within the Palaetropidae. Besides, Corparva gen. nov. can be differentiated from the rest Palaeotropidae by its apical system semi-ethmolytic and its labral plate reaching to rear part of second adjacent ambulacral plate. C. lyrida sp. nov. is known only from abyssal depths at the Mar del Plata Canyon on the Argentine continental slope, and it is sympatric with others spatangoids herein treated. This new genus and species represent the first report on the family Palaeotropidae from Argentina.

Many authors have pointed out the high incidence of benthic marine invertebrates with non-pelagic development and high rates of parental care in the SWAO and the Southern Ocean (Poulin & Féral, 1996, 1998; Pearse, Mooi, Lockhart & Brandt, 2009), and echinoids are not an exception. Although species of the genera Brisaster, and Tripylaster are broadcast spawners with indirect development through planktotrophic larvae, members of the genera Abatus, Tripylus, Parapneustes and Delopatagus are brooders and present a lecithotrophic development (Mortensen, 1951; Pearse & Cameron, 1991; Poulin & Féral, 1996; Gil, Zaixso & Tolosano, 2009). Also, the distinction between sexes in echinoids is frequently expressed by sexual dimorphism, such as the form of genital papillae and the size of genital pores (among others). Mostly in brooding spatangoids, the females present extreme secondary sexual features associated with this reproduction strategy, such as the modification of the aboral region of the test into marsupial brood pouches that give protection for the development of embryos and juveniles (David & Mooi, 1990; Gil, Zaixso & Tolosano, 2020). The depressed ambulacra as an aboral brooding system were widely described for different spatangoids taxa (Mortensen, 1951; Philip & Foster, 1971; Schinner & McClintock, 1993). Corparva lyrida sp. nov presents large gonopores and the paired ambulacra are deeply depressed forming rounded pouches. A lecithotrophic developmental mode for the species can be suspected, due to large gonopores is associated with the production of large yolky eggs (Pearse & Cameron, 1991). The apical system of C. lyrida sp. nov is sunken with respect to the extreme of the interambulacral areas and the ambulacral pouches are slightly deeper than the apical system as well, forming a wide sunken cruciform area (Fig. 3A). This area is cover by long primary spines that emerge leaned over towards the center of the animal body from the upper external edges of the ambulacral plates and surrounding interambulacral plates, and by pedicellariae (Fig. 2A), resulting in a protected chamber. Although no embryos, nor juveniles were found into the chamber, the morphological features previously mentioned suggesting that the specimen could be a female with marsupial brood chamber

Although is necessary to increase the sampling effort and use a proper experimental design to conclude on biogeographical issues, from this study some exploratory trends can be observed in the distribution of the spatangoids here studied (Fig. 1). The species composition in the SWAO has sub-Antarctic and Antarctic affinities. This could be explained in part by the presence of water masses formed in these regions of the world and they are carried to the SWAO by the MC, which could be acting as a dispersal vector of propagules and larvae. Recently studies about biogeographical patterns and benthic eco regionalization based on echinoids from the Southern Ocean, highlights the strongly faunal affinities between South America and sub-Antarctic islands, possibly due to the connectivity by the flow of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (Pierrat, Saucède, Brayard & David, 2013; Fabri-Ruiz, Danis, Navarro, Koubbi, Laffont & Saucède, 2020). However, is interesting to highlight that C. lyrida sp. nov. was found at 2 950 m depth at the Mar del Plata Canyon on the Argentine continental slope, and in this region between 2000 to 3000 m there is present the North Atlantic Deep Water (Voigt et al., 2013), which is originated at the North Atlantic Ocean, and flush southward along the continental slope of the American continent (Piola & Matano, 2001)

The present work brings novel and updated data about the diversity and distribution of spatangoid sea urchins from the SWAO, including the description of C. lyrida a new genus and species from abyssal waters off Argentina, new records, and occurrence of species previously reported. This reveals that there is still much to know about the diversity and distribution of heart urchins in the SWAO, especially from the deep-sea. Moreover, the knowledge in these aspects will contribute to clarify the matted phylogenetic and evolutionary relations among the Spatangoida taxa.

Ethical statement: authors declare that they all agree with this publication and made significant contributions; that there is no conflict of interest of any kind; and that we followed all pertinent ethical and legal procedures and requirements. All financial sources are fully and clearly stated in the acknowledgements section. A signed document has been filed in the journal archives.

uBio

uBio