The length-weight relationships (LWR) of fishes are im portant in fisheries biology because they allow the estimation of the average weight of the fish of a given length group by establishing a mathematical relation between the two (Mir, Mir, Patiyal & Kumar, 2014). Like any other morphometric characters, the LWR can be used as a character for the differentiation of taxonomic units and the relationship changes with the various developmental events in life such as metamorphosis, growth and on-set of maturity (Thomas et al., 2003). Besides this, the LWR can also be used in setting yield equations for estimating the number of fish landed and comparing the population in space and time (Beverton & Holt, 1957). LWR parameters (a and b) are useful in fisheries science in many ways: to estimate weight of individual fish from its length, to calculate condition indices, to compare life history and morphology of populations belonging to different regions (Petrakis & Stergiou, 1995) and to study ontogenetic allometric changes (Teixeira de Mello et al., 2006). Furthermore the empirical relationship between the length and weight of the fish enhances the knowledge of the natural history of commercially important fish species, thus making the conservation possible.

The Indian major carp, Labeo rohita (Hamilton, 1822), commonly known as 'Roho labeo' is a geographically widespread species in tropical freshwater of India and adjacent countries with considerable variation in growth parameters (Chondar, 1999). The existence of interpopu-lation differences may indicate local adaptations, either through phenotypic plasticity or genetic variability (Mir, Sarkar, Dwivedi, Gusain & Jena, 2014). Part of this inter-population variation results from differences in local environmental conditions (Begg, Cappo, Cameron, Boyle & Sellin, 1998). This species thrives well in lakes, ponds, rivers (Talwar & Jhingran, 1991), and is reported from brackish-water system also (Riede, 2004). A column feeder herbivore showing rapid growth in terms of flesh, Roho labeo is the most choice and prestigious culturable fishery in India and constitutes a main capture fishery of the Ganga, especially in the upper and lower stretches and tributaries. India is by far the largest producer of Roho labeo and the total global aquaculture production peaked in 2006, at nearly 16,5x105tonnes (FAO, 2006-2012).The major source of Roho labeo seed in India is contributed via the Ganga basin (Chondar, 1999). The fish grows to a maximum total length of 200cm (Frimodt, 1995). Recent studies have shown fall in the catches of Roho labeo across Ganga basin in India (Mir et al., 2014). To thwart this fall the generation of data on the growth condition of this species is an important task.

A number of reports are available on biological aspects of L. rohita from different water bodies (Varghese, 1973; Salam & Janjua, 1991; Sarkar, Negi & Deepak, 2006; Mir, Sarkar, Dwivedi, Gusain & Jena, 2013).The LWR studies on L. rohita are mostly restricted to cultured environments (Khan, 1972; Kamal, 1971; Sarkar, Medda, Ganguly & Basu, 1999). However, the information on LWR of L. rohita is scanty from its wild habitat, especially from the rivers under this study. For the successful management and conservation of wild populations of Roho labeo, it is important to understand the relationship between length and weight of this fish species in its natural environment. Therefore, aim of the present investigation was to provide information on this relationship in Roho labeo from its wild habitat across the Ganga basinin India.

Material & methods

Study area: The Ganges river basin is the fifth largest basin in the world and is located 70-88°30'E and 22°-31N. The length of main channel from the traditional source of the Gangotri Glacier in India is 2 550Km. Annual volume of water discharged by the Ganges is the fifth highest in the world, with a mean discharge rate of 18,7x103m3-sec-1 (Welcomme, 1985). The main sources of water in the basin are direct seasonal rainfall, mainly from the south west and glacial and snowmelt during the summer (Chapman, 1995). The main channel of the Ganges begins at the confluence of Bhagirathi and Alaknanda, which descend from upper Himalayas to Devprayag (520m above sea level) and receives a number of major tributaries (Figura 1). The northern tributaries principally include Ghagra, Gomti, Buri Gandak and Kosi and southern tribu tarles include Yamuna (Ken, Betwa), Son, Chambal, Tons, Kalisindh, Sharda and Damodar. Most of these tributaries are controlled by irrigation barrages and there are two major barrages across the main channel, one at Hardwar which abstracts much of the water at this point to irrigate the Doab region and one at Farakka which diverts water down to Calcutta (Mir et al., 2013). All of these structures modify the flow of the river and may considerably influence fish distribution. Fish and fisheries are both im portant resource and activity in their own right but also provide indicators of the overall impact of anthropogenic changes over the basin.

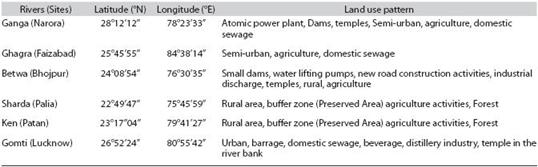

Sample collection: A total of 1 033 specimens of L. rohita were collected during March 2009 to July 2012 from six rivers of the Ganga basin in India (Figura 1). The si tes on selected rivers, GPS coordinates, land use pattern of the selected sites on these rivers are shown in Table 1. The samples were collected from the rivers (upstream, midstream and downstream) in the morning before the sunrise, by using cast nets (9m length, 9m breadth and 1/2cm mesh size) and drag nets (100m length, 20m breadth, 1/2cm mesh size), and also from the 18 landing centers present on these six rivers. Measurements on fish length and weight were taken; besides, fish were dissected and sexes identified at the respective collection si tes. Total length of each fish was taken from the tip of snout (mouth closed) to the extended tip of the caudal fin to the nearest 0,01mm by digital caliper and ruler and weighed to the nearest 0,01g (total weight) (by digital weighing machine, ACCULAB Sartorius Group).

Figura 1: Collection sites of L. rohita from three Indian rivers (Source Khan et al. (2013) with slight modifications).

Length-weight relationships: The relationships between length and weight of fish was analyzed by measuring length and weight of fish specimens collected from the study areas. The statistical relationship between these parameters of fishes was established by using the parabolic equation by Froese (2006).

W = aLb

where, W=weight of fish in grams, L=length of fish in mm, a=constant and b=an exponential expressing relationship between length-weight. The relationship (W = aLb) when converted into the logarithmic form gives a straight line relationship graphically.

Log W = Log a + b Log L

where b represents the slope of the line, Log a is a constant. Additionally, 95% confidence limits of b and the coefficient of determination r2 were estimated.

Results

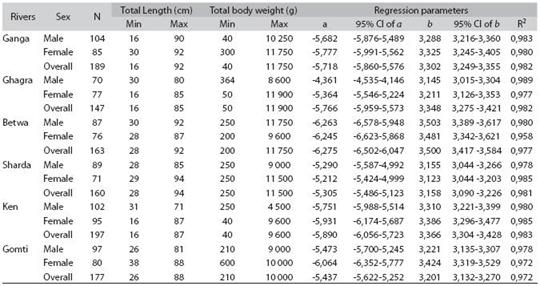

The regression parameters for length-weight relationships, coefficient of determination (r2), 95% confi dence interval of a and b, total length and body weight range in males, females and combined sexes is shown in Table 2. The linear regressions of different populations were highly significant (P<0,001). The regression coeffi cient (b) of LWRs of six rivers for this species was within the normal range of 2, 5-3, 5, as suggested by Froese (2006). A positive allometric growth (b >3) was observed.

Table 2: Total length and weight data, regression parameters and 95% confidence interval for Labeo rohita in different drainages of Ganga river basin in India

The overall value of r2 ranged from 0,958 in females of river Betwa to 0,989 in males of river Ghagra. All the populations exhibited positively allometric growth irrespective of sex (b>3; Figura 2).

Discussion

The growth coefficient (b) of our study was in accordance with the findings of Jhingran (1952), Ahmed and Saha (1996), Sarkar et al. (1999) and Bhat (2011) for Labeo rohita from different manmade water bodies. Jhingran (1952) reported value of regression coefficient (b= 3,0) for L. rohita from a moat and spring; Ahmed and Saha (1996) reported regression coefficient of L. rohita as 3,14 from Kaptai lake, Bangladesh; Sarkar et al. (1999) has observed the b value for bundh and hatchery as 3,30 and 3,12 respectively from Calcutta and Bhat (2011) reported growth coefficient (b) equal to 2,97 and coefficient of de-termination (r2) to be equal to 0,98 from Phuj reservoir, Jhansi. However, Choudhury, Kolekar and Chandra (1982) reported negative allometric growth (b = 2.347) from river Brahmaputra, Assam. According to Le Cren (1951), ecological conditions of the habitats or variation in the physiology of the animals, or both, are responsible for growth rate variations in the same species from different localities. In our study the growth condition is towards a declining trend from river to river. Similar results were obtained by Haniffa, Nagarajan and Gopalakrishnan (2006) in case of Channa punctatus from the rivers of Western Ghats. This provides evidence that the ecosystem might be the causative factor for the growth.

Even though the change in the b value depends primarily on the shape and fatness of the species, various factors may be responsible for the differences in the pa rameters of the length-weight relationships among sea-sons and years. According to Bagenal and Tesch (1978); Ozaydin, Uckun, Akalin, Leblebici and Tosunoglu (2007) and Mir, F.A. et al. (2014) the parameter b unlikely may vary seasonally, and even daily, and between habitats. Thus, the length-weight relationship in fish is affected by a number of factors including feeding, sex, maturity, specimen number, area, seasonal effects, degree of stomach fullness, habitat, health and general fish condition, differences in the observed length ranges of the specimen caught (Tesch, 1971; Khan, Miyan and Khan, 2013), only some of which were taken into account for the present study. Although plenty of work has been done on length-weight relationship of L. rohita from artificial water bodies like, ponds, moats etc., but the information available from the wild populations is scanty, especially for the rivers under this study.

This study is the first attempt to provide information about the growth condition of L. rohita from wild population of different geographical locations of river Ganga and its major tributaries. Our study will enlighten the biologists about the status and growth of this fish in na tural waters and this work will be useful for the fishery biologists and conservation agencies, for successful development, management, production and ultimate conservation of L. rohita.

uBio

uBio