-

“I beg leave to inform you, that the schooner ‘Snow’, captured by the Netherlands sloop-of-war, the ‘Kemphaan’, was condemned as prize on the 6th instant. Inclosed I have transmitted an abstraction of her case:

One of the Negro women taken in her died since her arrival, and after she had been landed in this colony: the remaining Slaves, forty-nine in number, have received their certificates of freedom, and have been placed by the Government under the care of that very useful and respectable religious body, the Moravians; to the end that, when sufficiently instructed in the truth of the Christian religion, they may all be baptized; after which, it is the intention of the Governor, to employ them as free laborers.

I am sorry to be under the necessity of informing you that one of the sailors found on board of the slave- schooner, named William Askens, is a British subject. […] I conceived it to be my duty to claim the above- mentioned William Askens of the Governor, for the purpose of having him sent by the earliest opportunity to some British settlement, with a copy of the sentence [---] that he may take his trial under the Act. 51 Geo, III, c, 23, for being engaged in the Slave Trade” (Lance, 1823, extract of a letter to George Canning, British Foreign Secretary, on May 11, 1823).

The letter cited above gives a good idea of the duties imposed on John Henry Lance (1793-1878) (Fig. 1), who in 1822 had been appointed as Judge in the Mixed Court of Justice in Paramaribo for 10 years (1823-1833). On May 1, 1807, after a long campaign by active abolitionists in and outside Parliament (Fig. 2), the British Parliament approved the Abolition Bill, containing a definitive prohibition of slave trading. It was England who, after the final victory over Napoleon, brought the question of slavery to the Congress of Vienna in 1814.

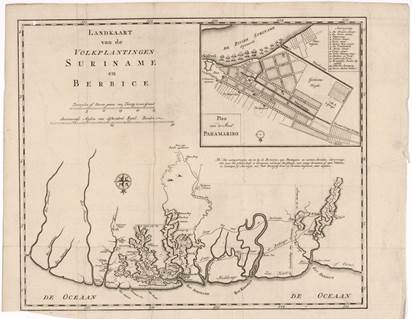

A condition of England’s recognition of the “new” Netherlands was that King Willem I should also prohibit slave trading. Both parties signed an agreement in 1818: [...] for preventing Their respective Subjects from engaging in any Traffic of Slaves... To ensure that the Netherlands would comply with this prohibition, so-called ‘Mixed Courts of Justice’ were established in Sierra Leone, on the West Coast of Africa, and at Paramaribo, Surinam (Fig. 3-4). [...] And it was by the said Treaty further stipulated and agreed, that said Courts should judge the Causes submitted to them according to the terms of said Treaty, without appeal, and according to the Regulations and Instructions annexed to the said Treaty […], and Whereas it was, by the said Regulations annexed to the said Treaty, that the said Mixed Courts of Justice […] should be composed in the following manner, that is to say: that the Two High Contracting Parties should each of them name a Judge and an Arbitrator (Ferrier 1983: 4, 6).

When Thomas Sherard Wale, the first English arbitrator appointed to the Mixed Court of Paramaribo, died suddenly in 1819, J.H. Lance was appointed as his successor.

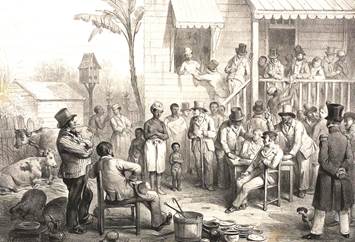

Surinam, like most other European colonies in the Caribbean area, based its economy on the plantation system (mostly sugar cane and coffee), and heavily depended on slave labor (Fig. 5). It is therefore understandable that the Dutch plantation owners tried to circumvent the conditions of the treaty, under which they could not increase the number of slaves through new ‘imports’, and had to employ hired labor instead.

It was under these circumstances that John Henry Lance arrived in Paramaribo on January 7, 1823. Lance was born in 1793 at Netherton, near Andover. His father, a clergyman, took much interest in giving his only male child the best education. Thus, J.H. Lance attended Eton College from 1810 to 1812, and in 1815 was admitted to the Middle Temple, one of the four Inns of Court entitled to call their members to the English Bar as barristers. In 1820 he was appointed to the Degree of the Utter Bar of the Inner Temple. Letters from his tutors and professors underlined his qualities as a talented and hard-working student with an exemplary character (Ferrier 1983: 8).

Figure 2 Am I Not a Man and a Brother? 1787 medallion designed by Josiah Wedgwood for the British anti- slavery campaign.

In Surinam, Lance’s days were filled with opportunities to absorb the values of the planter class. He spent nearly half his time on various estates, “sometimes on business & sometimes not” (Ben-Ur 2016: 6) (Fig. 6). A close friend of James Bateman and John Lindley, Lance shared their passion for plants, especially orchids, and his excursions from one plantation to the other gave him plenty of opportunities to collect orchids, of which he sent a number of new species to the nursery of George Loddiges.

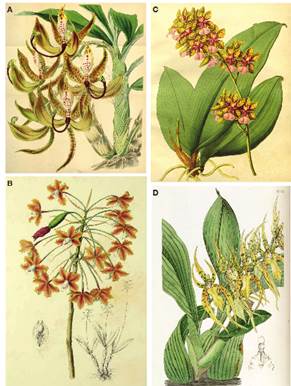

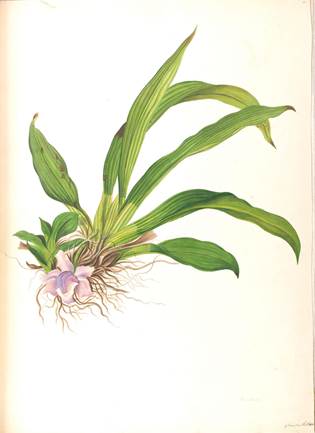

Cycnoches loddigesii Lindl. (Fig. 7A ), Pleurothallis lanceana Lodd., and Schomburgkia marginata Lindl. (Fig.7B) were described amongst Lance’s collections in Surinam.

A few others of his plants were named in his honor: Oncidum Lance anum Lindl. (Fig.7C), and Brassia lanceana Lindl. (Fig.7D).

By the end of his term in Surinam, John Henry Lance had become well adapted to life in the Dutch colony. Notwithstanding his position in the Mixed Court, he had no problem in accepting slavery in society as it was. He envied the proprietors he described, particularly the Dutch. Three quarters of them lived “quietly in Holland…doing nothing but receive their remittances which after all the usual rascality of their agents are still considerable.” In 1829, Lance was still trying to convince his father to become a co-investor. To assuage his “qualms… about being a holder of slaves,” Lance assured him that the slaves were “as happy & contended a race of people in this colony as your parishoners.” (Ben- Ur 2015: 7). When he embarked for his return to England, he had in his company two manumitted female slaves, and it is said that he once cracked a joke about his father acquiring a “Black” daughter- in-law.

Print by Giulio Ferraio.

Figure 4 View of Paramaribo, Surinam (1827) as it appeared during the Dutch colonial period. With ships and the fort Zeelandia on the right.

Oil on canvas by Willem de Klerk, ca. 1825.

Figure 6 View of the plantation Marienbosch at the Taparoepikanaal in Surinam.

Figure 7 A, Cycnoches loddigesii, from Hooker (1846). B, Schomburgkia marginata Lindl., from Lindley (1838). C, Oncidium lanceanum Lindl.from Lindley (1842). D, Brassia lanceana Lindl., from Lindley (1836).

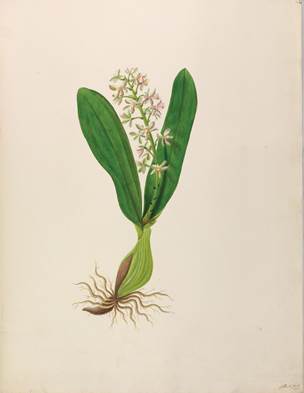

Well-known as a plant collector, Lance’s talent as a botanical illustrator went largely unknown during his time. It was not until Lindley, in 1838, described his Schomburgkia marginata from a plant collected by Lance in Surinam (Fig. 14) that illustrations of orchids by the hand of Lance were mentioned for the first time. “When Schomburgkia crispa was published a few months since in this work, mention was made of a second species of the genus, of which I had received specimens from Mr. Schomburgk. I have since been so fortunate as to find a beautiful coloured drawing of this curious epiphyte, among a valuable collection of figures of Surinam plants, made by direction of my friend John Henry Lance, Esq., during his residence in that colony. From these materials I have been allowed to prepare the accompanying figure, corrected from specimens in my herbarium” (Lindley 1838: under plate XIII). Sixty years later, in 1898, Robert A. Rolfe, in his obituary for James Bateman, mentions these illustrations again. Rolfe mentions a letter which he received in 1892 from Bateman, in which the latter wrote: Mr. Lance (after whom Oncidium Lanceanum is called), and who discovered Cycnoches Loddigesii in Surinam has not been dead many years. […] I remember going to his rooms in the Temple, together with Mr. Huntley (hence the genus Huntleya), who was a friend of his, where we feasted our eyes on a large portfolio of drawings (by Mr. Lance himself) which he brought with him from Surinam. Lindley, in a letter to me, describes his first visit to them in these words: ‘Oh! I have just seen such drawings of such things of Surinam - beautiful beyond description, and nearly all new!! (Rolfe 1898: 56-57).

Lance’s drawings would have remained largely unknown were it not for a fortunate accident. While searching for images about Lance and his plants on the Internet, the author found on the web page of the Lindley Library of the Royal Horticultural Society a beautiful illustration of a specimen of Passiflora laurifolia with the following title: Watercolour on paper of Passiflora laurifolia, by John Henry Lance (c.1793-1878). From volume I of Surinam Orchids Etc. from Nature. The Lindley library was immediately consulted and soon digital images were received of all orchids contained in this portfolio. In addition, two notes in volume II of Lance’s work had been copied. The first of them read:

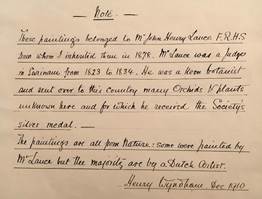

These paintings belonged to Mr. John Henry Lance F.R.H.S. from whom I inherited them in 1878. Mr. Lance was a judge in Surinam from 1823 to 1834. He was a keen botanist and sent over to this country many orchids & plants unknown here and for which he received the Society’s Silver Medal. The paintings were all from Nature: some were painted by Mr. Lance but the majority are by a Dutch Artist.

Henry Windham. Dec. 1910. (Fig. 8)

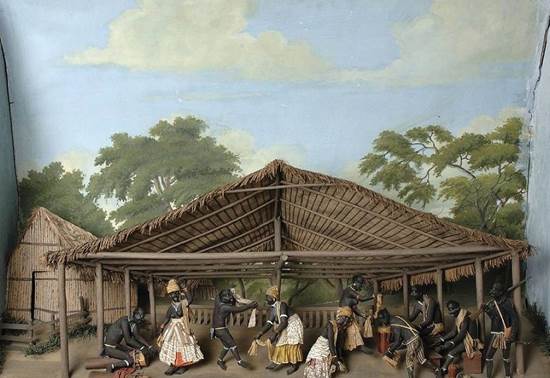

Wyndham’s note reveals an important fact: many of the flowers drawn in Lance’s work were not painted by him, but by a Dutch artist by the name of Gerrit Carl François Schouten (1779-1839). His relationship to Lance is not clear. However it seems probable that Schouten was engaged by Lance to paint plants for him. Schouten, a Surinamese born in Paramaribo and son of a Dutch government clerk and a local black woman, taught himself to paint and had become famous for his painted papier-maché dioramas of Surinamese life. These are flat boxes containing perspective, three-dimensional painted depictions of slave dances and city and plantation views among other themes. These dioramas, preserved today at Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, form a significant source of historical and topographical information about Surinam in the early 19th century (Fig. 9-10).

Courtesy and with permission of the Lindley Library, R.H.S.

Figure 8 Note in volume II of Lance’s Surinam orchids from nature.

An additional note in volume II of Lance’s work reads: These 2 volumes are presented to the R.H.S. by Henry Wyndham, Thornton Heath, Surrey. January 1878.

As to the paintings themselves, a few explanatory notes supplied by Charlotte Brooks, Art Curator of the Lindley Library, are of interest:

Most of the artworks are by Gerrit Carl François Schouten (1779-1839), and as such as signed ‘G Schouten fecit’ in ink, in the lower right or lower left corners.

A few paintings are signed ‘John Henry Lance fecit’, these tend not to be of the same quality as those by Schouten.

There are several paintings that are unsigned, but it may be possible to attribute these to Lance, judging them by the quality of the painting

There are other paintings that feature the initials ‘JHL’ in the lower right or left hand corner, in graphite pencil. This cannot be assumed to be a signature, though, as they appear on works signed by Schouten and unsigned paintings. It is more likely this was just an indication that the artworks belonged to Lance.

A total of 12 watercolors depicting Surinam orchids are preserved at the Lindley Library. Of these, seven were painted by Lance and six by Gerrit Schouten.

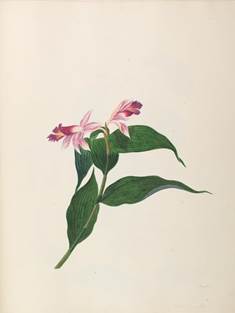

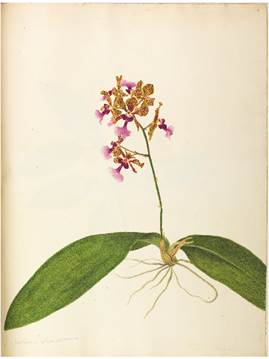

The species painted by John Henry Lance were: Brassavola angustata Lindl., Catasetum macrocarpum Rich. ex Kunth., Cycnoches ventricosum Bateman, Epidendrum schomburgki Lindl., Oncidium lanceanum Lindl., Schomburgkia marginata Lindl., and Sobralia sessilis Lindl. (Fig. 11-17).

By the hand of Gerrit Schouten were the illustrations of Aspasia variegata Lindl, Ionopsis utricularioides (Sw.) Lindl., Pescatoria violacea (Lindl.) Dressler, Prosthechea cf. crassilabia (Poepp. & Endl.) Carnevali & I.Ramírez, Rodriguezia secunda Kunth. and, Stanhopea grandiflora (Lodd.) Lindl. (Fig. 18-23).

A final anecdote: in 1834, Bateman sent a collector to Surinam named Thomas Colley. Several orchid species were published in the Botanical Register from Colley’s expedition. One of them was Oncidium lanceanum, of which John Lindley wrote in his Sertum Orchidaceum: […] John Henry Lance, Esq., upon his return to England from Surinam, where he had been residing several years, brought with him a considerable collection of orchideous epiphytes, which he presented to the society. Among other interesting species was the subject of the following memorandum; a plant than which a more acceptable addition to the hothouses of this country has seldom been made (Lindley 1838: 238). Bateman, full of pride, wrote that Colley had found a tree covered with this species and, knowing that Francis Henchman, another ‘traveler’ working for Low’s nursery was not far behind, stripped the tree of all the orchids. Bateman later said, without regret, that the species was not found before or since. He says rather boastfully, ‘Everyone was prepared to go down on their knees… offering their greatest treasures in exchange.’ This sad commentary reveals the unsustainable way that orchids were collected in Victorian times, even by those who were supposedly educated. (Siegel 2013:19).

With permission and under © of the Lindley Library, R.H.S.

Figure 11 Epidendrum schomburgki Lindl. Plate 101 of Surinam orchids from nature, by J.H. Lance.

With permission and and under © of the Lindley Library, R.H.S.

Figure 12 Cycnoches ventricosum Bateman. Plate 102 of Surinam orchids from nature, by J.H. Lance.

With permission and under © of the Lindley Library, R.H.S.

Figure 13 Sobralia sessilis Lindl. Plate 104 of Surinam orchids from nature, by J.H. Lance.

With permission and under © of the Lindley Library, R.H.S.

Figure 14 Schomburgkia marginata Lindl. Plate 115 of Surinam orchids from nature, by J.H. Lance.

With permission and under © of the Lindley Library, R.H.S.

Figure 15 Oncidium lanceanum Lindl. Plate 125 of Surinam orchids from nature, by J.H. Lancee.

With permission and under © of the Lindley Library, R.H.S.

Figure 16 Catasetum macrocarpum Rich. ex Kunth. Plate 124 of Surinam orchids from nature, by J.H. Lance.

With permission and under © of the Lindley Library, R.H.S.

Figure 17 Brassavola angustata Lindl. Plate 120 of Surinam orchids from nature, by J.H. Lance.

With permission and under © of the Lindley Library, R.H.S.

Figure 18 Aspasia variegata Lindl. Plate 072 of Surinam orchids from nature, by G. Schouten.

With permission and under © of the Lindley Library, R.H.S.

Figure 19 Pescatoria violacea (Lindl.) Dressler. Plate 080 of Surinam orchids from nature, by G. Schouten.

With permission and under © of the Lindley Library, R.H.S.

Figure 20 Ionopsis utricularioides (Sw.) Lindl. Plate 031 of Surinam orchids from nature, by G. Schouten.

With permission and under © of the Lindley Library, R.H.S.

Figure 21 Rodriguezia lanceolata Ruiz & Pav. Plate 049 of Surinam orchids from nature, by G. Schouten.

With permission and under © of the Lindley Library, R.H.S.

Figure 22 Stanhopea grandiflora (Lodd.) Lindl. Plate 055 of Surinam orchids from nature, by G. Schouten.

uBio

uBio