Introduction

The fishes of the Order Pleuronectifornes, commonly known as flatfish, are characterized by a laterally compressed body and the adults have both eyes on one side of the head. They live on the bottom sediments lying on one side of the body. Flatfish (flounders, tonguefish, soles) are benthic predators and some species can bury themselves in the sediments to avoid predators and search for prey. Because of their benthic habitat they are frequently captured incidentally as by-catch by trawl nets used by shrimp fishing vessels. Most of the adult tropical flatfish captured are of small size, with total lengths of less than 40 cm and only larger specimens are usually saved for local comsuption or for sale at fish markets. The number of pleuronectiform species worldwide has been estimated to be 1 042 (Nair & Gopalakrishnan, 2014).

There appears to be more species of flatfish in the tropics than in temperate regions, being tropical species relatively smaller than temperate ones (Pauly, 1994). Local factors such as depth, sediment type and oxygen concentration may influence their local diversity and distribution (Gibson, 1994). Tropical flatfish studies usually provide scarce information on species identifications, depth and sediment types. For the Pacific coast of lower Central America, a total of 37 species of flatfish have been reported belonging to the families Achiridae, Bothidae, Cynoglossidae, and Paralichthyidae (Bussing & López, 2015).

The Gulf of Nicoya estuary on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica has been its main fishing ground since the middle of the 20th century. Because of its commercial importance an ecological evaluation of its benthic fauna was conducted 40 years ago by the R.V. Skimmer using an otter trawl net at depths from 8 to 60 m and a list of species was published by Bartels, Price, López & Bussing (1983), Bartels, Price, López & Bussing (1984). More than a decade later during the R.V. Victor Hensen (hereinafter V. Hensen) expedition (1993-1994) the benthic fauna of the Gulf of Nicoya was sampled again with otter and beam trawl nets at depths from 10 to 228 m. The resulting fish list was published by Bussing & López (1996) and the ecological distributions were described by Wolff (1996). An updated list of the fish species collected in the Gulf of Nicoya by both vessels was published by, Vargas-Zamora, López-Sánchez and Ramírez-Coghi (2019) and yielded 32 species of flatfish (12 % of a total of 268 fish species) belonging to 13 genera (Achirus, Ancylopsetta, Cyclopsetta, Citharichthys, Engyophrys, Etropus, Hypoglossina, Monolene, Paralichthys, Perissias, Syacium, Symphurus and Trinectes). The richest genus was Symphurus, with 12 species.

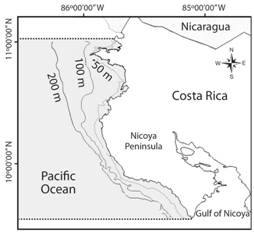

The fish fauna of the deep Golfo Dulce embayment on the Southern Pacific coast of Costa Rica was also sampled as part of the V. Hensen expedition and included the nearby Coronado Bay. The list of fish species from both areas and their distributions were published by Bussing & López (1996) and Wolff (1996), respectively. The fish fauna of the Northern waters of Costa Rica off the Nicoya Peninsula was sampled by the Nishin Maru shrimp trawler in 1987-1988 using an otter trawl and voucher specimens were deposited in the collection of the Museum of Zoology of the University of Costa Rica.

There are no reports focusing on the diversity and depth distribution of flatfish species along the Pacific coast of Central America. Updated information of the species diversity, depth distribution, and lengths of the species captured is important as a baseline for future studies aiming at the evaluation of the impact of local, regional and global stressors. Thus, the objective of this study is to provide complementary information on the presence, depth distribution and lengths of flatfish species collected by trawl nets in four coastal areas along the Pacific coast of Costa Rica.

Materials and methods

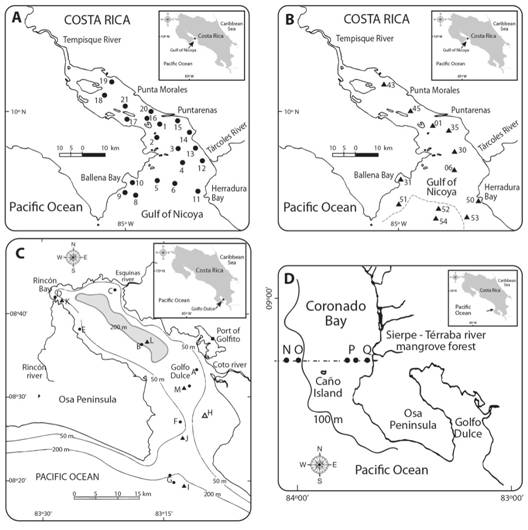

Most of the inner portion of the Gulf of Nicoya estuary is shallow (less than 50 m) and depth drops rapidly at the mouth. In contrast, the inner portion of the Golfo Dulce embayment is relatively deep (200 m) and has a sill (60 m) at the entrance. The Gulf of Nicoya is an estuary and its water dynamics have been described by Voorhis, Epifanio, Maurer, Dittel, and Vargas (1983). Golfo Dulce water circulation is more restricted, with hypoxic and anoxic waters below 100 m (Svendsen, Rosland, Myking, Vargas, Lizano, & Alfaro, 2006). The two adjacent areas to the Gulf of Nicoya and to Golfo Dulce are, respectively, those off the Nicoya Peninsula and the bay of Coronado and both are coastal platforms open to the Pacific Ocean. The stations sampled in the Gulf of Nicoya (Vessels Skimmer and V. Hensen), Golfo Dulce and Coronado Bay (V. Hensen) are illustrated in Fig. 1. The area off the Nicoya Peninsula sampled by the Nishin Maru shrimp trawler is illustrated in Fig. 2.

In order to assemble a list of flatfish species collected by the research vessels Skimmer and V. Hensen the publications by Bartels et al. (1983) and Bussing & López (1996) were consulted. In addition, we also consulted the updated list by Vargas-Zamora, et al. (2019) of fish species from the Gulf of Nicoya collected by both vessels. Station data from both vessels were found in Price, Bussing, Bussing, Maurer, and Bartels (1980) for the Skimmer, and in Wolff & Vargas (1994) for the V. Hensen survey.

Fig. 1 Trawl sampling stations. Pacific coast of Costa Rica. A. Gulf of Nicoya, R.V. Skimmer (1979-1980, 20 stations, 8 to 60 m deep). B. Gulf of Nicoya, R.V. Victor Hensen (1993-1994, 12 stations, 10 to 228 m), dashed line indicates the 100 m depth contour. C. Golfo Dulce, R. V. Victor Hensen (1993-1994, 13 stations, 20 to 235 m) The shaded area includes depths over 200 m. D. Coronado Bay, R.V. Victor Hensen (1993-1994, 5 stations, 21 to 187 m).

Fig. 2 Shaded area: sampling zone (56-359 m) of the Nishin Maru shrimp trawler 1987-1988 For station positions see Table 4, Pacific coast of Costa Rica.

Data on the species collected and depth distribution from the Nishin Maru survey off the Nicoya Peninsula were obtained from the Museum of Zoology, University of Costa Rica (MZUCR) catalogue cards. We also accessed the catalogue cards and flatfish specimens from the research vessels Skimmer and V. Hensen deposited in the collection of the Museum of Zoology. The names of several flatfish species were updated based on the web page World Register of Marine Species - WoRMS (http://www.marinespecies.org/). Data on length and depth distribution of the species from the Gulf of Nicoya, Coronado Bay, and Golfo Dulce were obtained from the cruise reports by Price et al. (1980) and Wolff & Vargas (1994). We also consulted information on depth available at the Shore Fishes of the Eastern Pacific: online Information Systemweb page(Robertson & Allen, 2015). Presence-absence data matrices of species per station were assembled for the Gulf of Nicoya and Golfo Dulce based on the report of the V. Hensen cruise (Wolff& Vargas, 1994). Cluster analyses were performed to display the similary of stations based on the species composition. The Gulf of Nicoya matrix was made of 31 species x 12 stations, while the matrix for Golfo Dulce was based on 19 species x 13 stations. The matrices were analyzed with the program PAST (Hammer, Harper, & Ryan, 2001) using the Sorensen similarity index.

Limited information was available from the National Institute of Fisheries and Aquaculture of Costa Rica (INCOPESCA) on landings of shrimp and by-catch (including flatfish) by the semi-industrial fleet operating on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica. The available data does not include species identifications. Total landings (kilograms of shrimp and bycatch including flatfish) from the semi-industrial fleet (vessels 17.3-27.6 m long) were available for the period 2000-2016. We visited (December 10, 2019) the fish counters at the Municipal Market of the port city of Puntarenas (Gulf of Nicoya) to verify if flatfish were offered there for sale.

Results

The total number of species of flatfish found at the four sites on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica was 36. There were 35 species collected by the Skimmer and V. Hensen (Table 1) while the 36th species (Monolene danae)was collected by the Nishin Maru shrimp trawler off the Nicoya Peninsula at depths from 107 to 250 m. The family Paralichthyidae included 13 species of the genera Ancylopsetta (1), Citharichthys (2), Cyclopsetta (2), Etropus (2), Hippoglossina (2), Paralichthys (1) and Syacium (3). The Cynoglossidae was represented by 12 species of the genus Symphurus. The Achiridae had six species of the genera Achirus (3) and Trinectes (3).The Bothidae included five species of the genera Engyophrys (1),Monolene (3) and Perissias (1). Specimens of the family Pleuronectidae were not found in the four sites sampled. The most speciose genus was Symphurus with 12 species.

TABLE 1 List of species of flatfish collected by the R.V. Skimmer (1979-1980, Gulf of Nicoya) and R.V. Victor Hensen (1993-1994, Gulf of Nicoya and Golfo Dulce). Pacific. Costa Rica

| No. | Species | A | B | C | D | E |

| 01. | Achirus klunzingeri (Steindachner, 1880) | * | 19 | 15 - 64 | 40 | |

| 02. | Achirus mazatlanus (Steindachner, 1869) | * | * | 30 | 8 - 64 | 60 |

| 03. | Achirus scutum (Günther, 1862) | * | * | 14 | 8 - 50 | 46 |

| 04. | Ancylopsetta dendritica Gilbert, 1890 + | * | 35 | 22 - 60 | 100 | |

| 05. | Citharichthys gilberti Jenkins & Evermann, 1889 | * | * | 16 | 8 - 228 | 48 |

| 06. | Citharichthys platophrys Gilbert, 1891 + | * | * | 12 | 8 - 228 | 145 |

| 07. | Cyclopsetta panamensis (Steindachner, 1876) + | * | * | 37 | 15-235 | 114 |

| 08. | Cyclopsetta querna (Jordan & Bollman, 1890) + | * | 43 | 8 - 65 | 92 | |

| 09. | Engyophrys sanctilaurentii Jordan & Bollman, 1890 | * | * | 16 | 15-235 | 235 |

| 10. | Etropus crossotus Jordan & Gilbert, 1882 + | * | 17 | 8 - 45 | 65 | |

| 11. | Etropus peruvianus Hildebrand, 1946 + | * | * | 13 | 15 - 65 | 45 |

| 12. | Hippoglossina bollmani Gilbert, 1890 + | * | N | 22 - 84 | 191 | |

| 13. | Hippoglossina tetropthalma (Gilbert, 1890) + | * | 31 | 22 - 65 | 233 | |

| 14. | Monolene asaedae Clark, 1936 | * | 11 | 187 - 200 | 209 | |

| 15. | Monolene maculipinna Garman, 1899 | * | * | 11 | 22 - 235 | 385 |

| 16. | Paralichthys woolmani Jordan & Williams, 1897 + | * | 25 | 22 - 84 | 91 | |

| 17. | Perissias taeniopterus (Gilbert, 1890) | * | N | 61 | 160 | |

| 18. | Syacium cf longidorsale Murakami & Amaoka, 1992 | * | * | 8 | 22 - 200 | 40 |

| 19. | Syacium latifrons (Jordan & Gilbert, 1882) + | * | * | 24 | 17 - 74 | 95 |

| 20. | Syacium ovale (Günter, 1864) + | * | * | 50 | 19 - 74 | 90 |

| 21. | Symphurus atramentatus Jordan & Bollman, 1890 | * | * | 15 | 35 - 228 | 120 |

| 22. | Symphurus callopterus Munroe & Mahadeva, 1989 | * | 40 | 30 - 235 | 320 | |

| 23. | Symphurus chabanaudi Mahadeva & Munroe, 1990 | * | 20 | 8 - 45 | 60 | |

| 24. | Symphurus elongatus (Günter, 1868) | * | * | 13 | 10 - 192 | 100 |

| 25. | Symphurus fasciolaris Gilbert, 1892 | * | N | 35 - 65 | 150 | |

| 26. | Symphurus gorgonae Chabanaud, 1948 | * | * | 10 | 19 - 228 | 120 |

| 27. | Symphurus leei Jordan & Bollman, 1890 | * | * | 9 | 15 - 228 | 115 |

| 28. | Symphurus melanurus Clark, 1936 | * | 22 | 8 - 65 | 35 | |

| 29. | Symphurus melasmatotheca Munroe & Nizinski, 1890 | * | * | 10 | 30 - 228 | 110 |

| 30. | Symphurus oligomerus Mahadeva & Munroe, 1990 | * | * | 12 | 32 - 200 | 300 |

| 31. | Symphurus undecimplerus Munroe & Nizinski, 1990 | * | N | 22 | 55 | |

| 32. | Symphurus williamsi Jordan & Cuvier, 1895 | * | N | 16 - 118 | 55 | |

| 33. | Trinectes fimbriatus (Günter, 1862) | * | 9 | 8 - 50 | 40 | |

| 34. | Trinectes fonsecensis (Günter, 1862) | * | 20 | 8 - 28 | 107 | |

| 35. | Trinectes xanthurus Walker & Bollinger, 2001 | * | 8 | 8 - 60 | 25 | |

| 36. | Monolene danae Bruun, 1937 | It was found only by the research vessel Nishin Maru at depths between 107 and 250 m |

A. Gulf of Nicoya, B. Golfo Dulce. C. Maximum total lenght (cm) of fish captured in both estuaries (N = no data). D. Depth (m) or depth range where captured. E. Maximum depth reported for the species by Robertson & Allen (2015).

List of flatfish species based on data from Bartels et al. (1983), Bussing & López (1996), Wolff (1996) and on specimens catalogued in the fish collection of the Museum of Zoology (MZUCR).Length data (C) from Price et al. (1980), and Wolff and Vargas (1994). + Species listed by Fischer et al. (1995) as commercially exploited in the Tropical Eastern Pacific.

The Gulf of Nicoya estuary yielded 27 species during the Skimmer expedition over a depth range of 8 to 60 m, while 31 species were found there during the V. Hensen survey at depths from 10 to 228 m. In the Gulf of Nicoya, the richest locality was station 31 (45 m depth) with 16 species captured by the Skimmer and 13 by the V. Hensen (22 m). The V. Hensen survey in Golfo Dulce yielded 19 species (Table 1) at depths from 23 to 235 m. The most diverse stations there were E (7 species, 40 m depth) and G (7 species, 200 m).

The maximum total lengths (TL) of the 30 species measured from both the Gulf of Nicoya and Golfo Dulce are included in Table 1 and ranged between 8 cm (Syacium cf longidorsale, Trinectes xanthurus) and 50 cm (S. ovale). Only 12 species were found with lengths over 20 cm. The mean maximum total length of the 30 species was 20 cm. Thirty-five species were collected over a depth range of 10 to 235 m in the Gulf of Nicoya and Golfo Dulce. Sixteen species were found there at greater depths than those reported in the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute web page (Robertson & Allen, 2015): Citharichthys gilberti, C. platophrys, Cyclopsetta panamensis, Etropus peruvianus, Paralichthys woolmani, Syacium cf longidorsale, Symphurus atramentatus, S. elongatus, S. gorgonae, S. leei, S. melasmatotheca, S. melanurus, S. undecimplerus, S. williamsi, Trinectes fimbriatus and T. xanthurus (Table 1).

The most frequently captured species in the Gulf of Nicoya, during the V. Hensen expedition, were Symphurus chabanaudi and S. elongatus (6 stations each, Table 2) while eight species were found at one station each (Table 2). The most frequently captured species in Golfo Dulce was Symphurus leei (5 stations). Six species were found at one station each (Table 2).

TABLE 2 R.V. Victor Hensen survey. Species present in four or more of the stations in the Gulf of Nicoya (12 stations) and Golfo Dulce (13 stations) and species found in one station only

| Species | Total | Station codes | |

| A. Gulf of Nicoya | |||

| Symphurus chabanaudi | 6 | 01 30 31 35 43 45 | |

| Symphurus elongatus | 6 | 01 06 30 35 43 53 | |

| Citharichthys platophrys | 5 | 01 06 52 53 54 | |

| Achirus mazatlanus | 4 | 31 35 31 51 | |

| Cyclopsetta querna | 4 | 06 30 35 45 | |

| Syacium ovale | 4 | 06 35 50 51 | |

| Symphurus gorgonae | 4 | 01 35 53 54 | |

| Symphurus oligomerus | 4 | 06 50 52 53 | |

| Symphurus williamsi | 4 | 01 31 35 52 | |

| Achirus scutum | 1 | 45 | |

| Ancylopsetta dendritica | 1 | 31 | |

| Etropus crossotus | 1 | 35 | |

| Perissias taeniopterus | 1 | 51 | |

| Symphurus melasmatotheca | 1 | 54 | |

| Symphurus undecimplerus | 1 | 31 | |

| Trinectes fonsecensis | 1 | 45 | |

| Trinectes xanthurus | 1 | 45 | |

| B. Golfo Dulce | |||

| Symphurus leei | 5 | A B C E G | |

| Cyclopsetta panamensis | 4 | D E H I | |

| Syacium latifrons | 4 | C E F H | |

| Symphurus callopterus | 4 | D G I M | |

| Monolene maculipinna | 3 | G M I | |

| Achirus scutum | 1 | H | |

| Etropus peruvianus | 1 | E | |

| Monolene danae | 1 | G | |

| Syacium cf longidorsale | 1 | G | |

| Symphurus elongatus | 1 | B | |

| Symphurus oligomerus | 1 | G | |

| Location | Station | Number of species | |

| C. Total number of species found at each station. Pacific coast, Costa Rica. | |||

| Gulf of Nicoya | 01 | 7 | |

| 06 | 6 | ||

| 30 | 4 | ||

| 31 | 13 | ||

| 35 | 12 | ||

| 43 | 2 | ||

| 45 | 10 | ||

| 50 | 2 | ||

| 51 | 9 | ||

| 52 | 6 | ||

| 53 | 9 | ||

| 54 | 6 | ||

| Golfo Dulce | A | 1 | |

| B | 3 | ||

| C | 3 | ||

| D | 6 | ||

| E | 7 | ||

| F | 5 | ||

| G | 7 | ||

| H | 3 | ||

| I | 4 | ||

| J | 0 | ||

| K | 0 | ||

| L | 0 | ||

| M | 3 | ||

Data from Bussing & López (1996), Wolff & Vargas (1994), Wolff (1996) and specimens catalogued in the collection of Museum of Zoology (MZUCR).

The V. Hensen survey in Coronado Bay yielded 17 species in depths from 21 to 187 m (Table 3). Based on the collections deposited in the Museum of Zoology, a total of 13 species were collected off the Nicoya Peninsula by the Nishin Maru shrimp trawler over a depth range of 56 to 359 m (Table 4). When the four areas sampled are considered together, a total of 21 species (58 %) were found at depths greater than 100 m. Monolene asaedae was collected at the deepest water range(254-359 m) off the Nicoya Peninsula (Table 4 and Table 5).

TABLE 3 List of species of flatfish from a transect (21 to 187 m deep) in front of the Térraba-Sierpe river mouth (Coronado Bay, Southeast Pacific coast of Costa Rica) collected by the R.V. Victor Hensen

| Species | Stations | Geographic Position | Depth (m) |

| Achirus mazatlanus | Q | 08o47’ - 84o41’ | 21 |

| Ancylopsetta dendritica | Q | 08o47’ - 84o41’ | 21 |

| Citharichthys gilberti | Q | 08o47’ - 84o41’ | 21 |

| Citharichthys platophrys | O, P | 08o47’ - 84o00’ & 08o46’ - 83o46’ | 103 & 48 |

| Cyclopsetta panamensis | P, Q | 08o46’ - 83o46’ & 08o47’ - 84o41’ | 48 & 21 |

| Cyclopsetta querna | P | 48 | |

| Engyophrys sanctilaurentii | O, P | 08o47’ - 84o00’ & 08o46’ - 83o46’ | 103 & 48 |

| Hippoglossina bollmani | N | 08o47’ - 84o03’ | 187 |

| Monolene asaedae | N | 08o47’ - 84o03’ | 187 |

| Monolene maculipinna | N, O | 08o47’ - 84o03’ & 08o47’ - 84o00’ | 187 & 103 |

| Symphurus callopterus | N, O | 08o47’ - 84o03’ & 08o47’ - 84o00’ | 187 & 103 |

| Symphurus elongatus | Q | 08o47’ - 84o41’ | 21 |

| Symphurus gorgonae | N, O | 08o47’ - 84o03’ & 08o47’ - 84o00’ | 187 & 103 |

| Symphurus leei | P | 08o46’ - 83o46’ | 48 |

| Symphurus oligomerus | N | 08o47’ - 84o03’ | 187 |

| Syacium latifrons | N | 08o47’ - 84o03’ | 187 |

| Syacium ovale | P | 48 |

Data from Bussing & López (1996), Wolff & Vargas (1994), Wolff (1996) and specimens catalogued in the collection of the Museum of Zoology (MZUCR)

TABLE 4 List of species of flatfish based on specimens collected by a shrimp trawler (Nishin Maru, 1987-1988) in coastal areas (56 to 350 m deep) on the Northwest Pacific (off Nicoya Peninsula) of Costa Rica and deposited in the collection of the Museum of Zoology (MZUCR)

| Species | Latitude N - Longitude W | Depth range, m |

| Engyophrys sanctilaurentii | 09o37’ - 85o30’ 10o19’ - 85o52’ | 65 - 85 111 |

| Hippoglossina bollmani | 10o44’ - 86o09’ | 189 - 193 |

| Hippoglossina tetropthalma | 10o40’ - 85o50’ 10o30’ - 86o02’ 10o42’ - 85o54’ | 165 102 56 - 72 |

| Monolene asaedae | 10o58’- 86o31’ 10o52’ - 86o33’ 10o45’ - 86o18’ 09o45’ - 85o27’ 10o34’ - 86o16’ 11o00’ - 86o32’ 10o25’ - 85o55’ 10o06’ - 85o58’ 10o47’ - 86o14’ 10o45’ - 86o15’ 10o47’ - 86o18’ 11o00’ - 86o17’ | 168 - 179 188 - 205 207 85 255 - 258 159 - 180 68 - 72 107 - 250 203 - 206 206 - 215 245 - 359 159 - 164 |

| Monolene danae | 10o06’ - 85o58’ | 107 - 250 |

| Monolene maculipinna | 10o52’ - 86o33’ 10o07’ - 85o51’ 10o04’ - 85o52’ 10o33’ - 86o 02’ 10o23’ - 85o55’ 10o34’ - 86o10’ 10o34’ - 86o14’ | 188 - 205 71 - 82 65 - 170 102 - 178 67 - 70 156 - 182 215 - 225 |

| Syacium ovale | 09o41’ - 85o21’ | 220 |

| Symphurus atramentatus | 10o44’ - 85o49’ | 61 - 82 |

| Symphurus callopterus | 10o04’ - 85o52’ 10o54’ - 86o22’ 10o08’ - 85o52’ 10o32’ - 85o53’ 11o00’ - 86o32’ 10o42’ - 85o54’ 10o37’ - 85o55’ 10o07’ - 85o50’ 10o55’ - 86o03’ 10o37’ - 86o05’ | 65 - 170 191 - 192 67 - 106 80 - 85 159 - 180 56 - 72 91 - 93 72 - 89 116 - 144 134 - 139 |

| Symphurus chabanaudi | 10o34’ - 86o10’ | 156 - 182 |

| Symphurus gorgonae | 10o33’ - 86o02’ | 102 - 178 |

| Symphurus leei | 10o46’ - 85o51’ 11o01’ - 86o00” | 63 - 78 102 - 103 |

| Symphurus oligomerus | 10o45’ - 86o18’ | 207 |

TABLE 5 List of 21 species of flatfish found at depths deeper than 100 m in the four areas sampled on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica

| Species | Maximum depth (m) |

| Citharichthys gilberti | 228 |

| Citharichthys platophrys | 228 |

| Cyclopsetta panamensis | 235 |

| Engyophrys sanctilaurentii | 235 |

| Hippoglossina bollmani | 193 |

| Hippoglossina tetropthalma | 165 |

| Monolene asaedae | 359 |

| Monolene danae | 250 |

| Monolene maculipinna | 235 |

| Syacium ovale | 220 |

| Syacium latifrons | 187 |

| Syacium cf longidorsale | 200 |

| Symphurus atramentatus | 228 |

| Symphurus callopterus | 235 |

| Symphurus chabanaudi | 182 |

| Symphurus elongatus | 192 |

| Symphurus gorgonae | 228 |

| Symphurus leei | 228 |

| Symphurus melasmatotheca | 228 |

| Symphurus oligomerus | 207 |

| Symphurus williamsi | 118 |

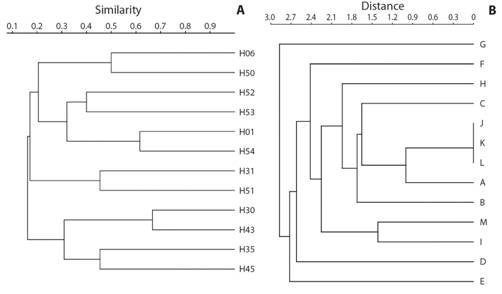

Cluster analysis from the V. Hensen data grouped the stations based on the similarity of the presence or absence of species at the stations (Fig. 3).The cluster for the Gulf of Nicoya may be interpreted as composed by three main groups (Fig. 3A). Group 1 has three subgroups of which the first includes stations 06 (6 spp 43 m deep) and 50 (2 spp, 32 m). The two species present in station 50 (Symphurus oligomerus and Syacium ovale) were also present in station 06.The second subgroup has two deep stations at the mouth of the estuary: station 52 (6 spp, 118 m) and 53 (9 spp, 84 m). The third subroup is composed by two distant stations 01 (7 spp, 35 m) and 54 (6 spp, 228 m), which have four species in common. Group 2 includes stations near Ballena Bay: station 31 (13 spp, 22 m) and 51 (9 spp, 64 m). Group 3 encloses two subgroups, the first is made by two distant stations: 30 (4 spp, 30 m, ) and 43 (2 spp, 10 m) which have two species in common (Symphurus chabanaudi and S. elongatus). The second subgroup comprises stations 35 (12 spp, 19 m) and 45 (10 spp, 15 m). Two pairs of stations (52-53, 31-51) that are closer geographically were grouped.

The cluster analysis for the V. Hensen Golfo Dulce data have no geographically closer stations grouped together and may comprise six main groups (Fig. 3B). Group 1 includes station G (7 species, 200 m deep). Group 2 comprise station E (7 spp, 40 m). Stations G and E have only two species in common: Symphurus leei and S. gorgonae. Group 3 is only composed by station D (6 spp, 30 m). Group 4 comprise station F (5 spp, 74 m). Group 5 is made of two stations: I (4 spp, 235 m) and M (3 spp, 82 m). Stations M and I have two species in common: S. callopterus and Monolene maculipinna. Group 6 includes seven stations in four subgroups: one made by station B (3 spp, 192 m) and another by station H (3 species, 23 m). A third subgroup is represented by station C (3 spp, 45 m). Stations B and C have S. leei in common, while C and H have Syacium latifrons in common. The fourth subgroup is represented by station A (107 m) with only S. leei captured, and three stations (J, 52 m; K, 54 m; L, 194 m) with no species found. No clear trends were found with depth.

Data obtained directly from INCOPESCA for the period 2000-2016 is included in Fig. 4. A minimum of 365.5 kg of flatfish was discharged in 2001 representing 0.03 % of the total 1 289 951.5 kg of shrimp and bycatch landed. A peak of 2 825 707 kg of shrimp and bycatch, of which 13 414 kg (0.47 %) were flatfish was reported for the year 2013 followed by a decline. A total of 694 287 kg of shrimp and bycatch was discharged in 2016 of which flatfish were represented by 1 126 kg (0.16 %). The relative percentage of flatfish in the total captures over the period 2000-2016 was small (mean 0.19 %) with a maximum of 0.57 % (8 113 kg) for the year 2004 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3 R.V. Victor Hensen (1993-1994). Dendogram resulting from cluster analysis (Sorensen index). A. Gulf of Nicoya (31 species x 12 stations). B. Golfo Dulce (19 species x 13 stations). No species were found at stations J, K & L. Pacific coast of Costa Rica.

Fig. 4 Total landings (kg) by the semi-industrial fishing fleet (vessels of 17.3 to 27.6 m long) for the period 2000-2016. A. Total landings (shrimp and bycatch including fish, kg x 106). B. Total landings of flatfish, kg x 103. C. Percentage (%) of the total landings represented by flatfish. Pacific coast of Costa Rica.

During our visit to the Municipal Market we found only one store selling a few flatfish (Possibly Etropus crossotus). The longest (estimated at 40 cm) headless and evisceratedspecimen had a weight of 950 gr.

Discussion

Data on the species richness and depth distribution of flatfishes from the Eastern Tropical Pacific are scarce. However, the number of flatfish species of the Pacific coast of Costa Rica appears comparable to that found in other tropical regions such as that reported for the Kerala coast (8o N) of India where 34 species and 17 genera were present in bycatch collections (Bijukumar & Deepthi, 2009). In contrast, a study in a Guinea-Bissau estuary (11o N, Africa) collected eight flatfish species using a beam trawl net (Van der Veer et al., 1995). Other factors such as depth, environmental parameters, sampling effort and gear type may influence the local number of species of this group of fishes as discussed by Gibson (1994). A relatively high number of species of flatfish was also found in a temperate embayment (35o N, Wakasa Bay, Japan) where 41 species were captured between 60 to 260 m (Minami & Tanaka,1992). In contrast, studies in other temperate regions indicate lower numbers particularly in shallow embayments: A beam trawl study of the Sado estuary (38o N, 10 m deep, Portugal) yielded 12 species and seven genera (Nogueira-Cabral, 2000). A beam trawl survey of the shallow Barataria Bay estuary (29o N, 2 m deep, U.S.A,) captured only seven species (Allen & Baltz, 1997). Moreover, the Guanabara Bay estuary in Brazil (22.5o S, 1 to 30 m deep) yielded 16 species (Silva-Junior, Santos, Chagas-Macedo, Numan, & Vianna, 2019), while the nearby Sepetiba Bay (23o S, less than 5 m deep) was characterized by five species (Guedes & Araujo, 2008). For the Eastern Tropical Pacific region Minami &Tanaka (1992) reported 92 species of flatfish. On this region a study on the Gulf of California (25o N, Mexico) 15 species of five families were reported there at depths from 10 to 64 m by Rábago-Quiróz, López-Martínez, Herrera-Valdivia. Nevárez-Martínez, & Rodríguez-Romero (2008). Most of the above-mentioned studies were conducted in shallow waters. The relatively high number of species found by trawling in Costa Rica was probably related to the wide water depth range (8 to 359 m) covered by the three survey vessels, the numerous stations, and the use of otter and beam trawl nets during de V. Hensen survey.

This greater range also allowed sampling over a variety of sediment types ranging from sand to mud and mixtures of both. Flatfish live on bottom sediments whose composition may influence fish habitat preferences, as the study by Stoner and Abookire (2002) indicates for the Alaskan Hippoglossus stenolepis. There are some data on the sediment composition found in the Gulf of Nicoya by the Skimmer expedition (Vargas, Dean, Maurer, & Orellana, 1985) and in Golfo Dulce by the V. Hensen survey (León-Morales & Vargas, 1998) indicating a wide range of patchy sediment types, from very soft muds to compact mixtures. However, sedimentary sampling stations differ from those of the fish surveys and a clear association of fish distribution with sediment types based on those reports is difficult to assess.

The results of the cluster analyses probably reflect habitat preferences among the flatfish species inhabiting the Gulf of Nicoya and Golfo Dulce. The fact that over 30 species can coexist is important in the particular context of the various species of Symphurus found in both embayments. The benthic invertebrate fauna of both ecosystems includes a variety of possible food items with a patchy distribution over different mixtures of sediments (Maurer & Vargas, 1984; Vargas et al, 1985; León-Morales & Vargas, 1998) that may influence habitat partitioning by flatfish. In addition, both systems include many other species of fish (Vargas-Zamora et al2019) as potential prey items. Habitat partitioning by five species of flatfish based on different prey items has been reported by Guedes and Araujo (2008) for a tropical bay in Brazil. Accoring to Cabral, Lopes and Loeper (2002) members of the family Bothidae are day active predators while those of the familiy Soleidae are mostly night feeders. This different behaviours may serve to facilitate coexistence of the assemblages of flatfish species in the four areas sampled on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica.

The size range of flatfish reported by Rábago-Quiróz et al. (2008) for the Gulf of California was from 2 to 38 cm, with only a few individuals of the genera Paralichthys longer than 25 cm. They also reported maximum size ranges found in the literature for several species which are also found in the Pacific coast of Costa Rica, like: Achirus mazatlanus (21 cm), Citharichthys gilberti (27 cm), Etropus crossotus (20), Paralichthys woolmani (80 cm), Symphurus chabanaudi (25 cm) and Syacium ovale (23 cm). Of the species collected in Costa Rica, A. mazatlanus (30 cm) and S. ovale (50 cm) appear to be length records for the region. Thus, the range of maximum total lengths for the 36 species found in this study (8-50 cm) appears as expected for the region, with several exceptions.

Rábago-Quiróz, López-Martínez, Nevárez-Martínez, & Morales-Bojorquez (2015) also suggested that flatfishes of less than 13.7 cm were recruits. If we accept this length, a total of 14 species found in this study were problably recruits. This fact emphasizes the negative impact of benthic trawling gear on the marine benthos (Campos, Burgos & Gamboa, 1984; Jones, 1992).

On the Pacific coast of Costa Rica at least 21 species (58 % of total) were found in waters deeper than 100 m and thus probably exposed to low oxygen concentrations characteristic of hypoxia. The results of the V. Hensen expedition indicate that low oxygen concentrations were found in waters deeper than 100 m at the mouths of both the Gulf of Nicoya and Golfo Dulce (Wolff & Vargas, 1994; Vargas-Zamora et al 2019). These low oxygen concentrations were close or below 2 mg O2 / L, an accepted indicator of hypoxia (Hofmann, Peltzer, Waltz, & Brewer, 2011). Oxygen concentrations as low as 0.2 mg / L were found at a 200 m deep station in the inner portion of Golfo Dulce (Acuña-González, Vargas-Zamora, & Córdoba-Muñoz 2006). However, information on the tolerance of tropical flatfish to low oxygen concentrations is scarce. The report by Switzer, Chesney, and Baltz (2009) who studied the distribution of seven species from the Northern Gulf of Mexico found that hypoxic environments were generally avoided by flatfishes leading to large areas unsuitable for many species.

The expeditions of the research vessels Skimmer, V. Hensen and Nishin Maru took place in 1979-1980, 1987-1988 and 1993-1994, respectively. During those years a relatively large fleet of shrimp trawlers was operating on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica. Fisheries statistical data for the period 1987-2005 are available in Araya, Vásquez, Marín, Palacios, Soto, Mejía, Shimazu, and Hiramatsu (2007) but their study focused on other commercially important fish species and shrimp rather than on flatfish. However, they included photographs of 12 local species of flatfish. The number of trawlers has been drastically reduced recently and the remaining trawl fishing licences expired in 2018. A few flatfish are presently captured by other types of gear and are occasionally offered for sale at local markets.

The data gathered by the National Fisheries Institute (INCOPESCA) from 2000-2016 includes the total captures of flatfish (not identified to species level) by the semi-industrial fleet. The relative importance of these captures is below 1 %. This percentage is lower than that reported by Rábago-Quiróz et al. (2015) for the Gulf of California where flatfishes represented between 5 to 10 % of the total by-catch. According to Nair and Gopalakrishnan (2014) flatfish landing data around the world generally do not include species identifications and 54-80 % of landings of tropical flatfish are of unidentified species. Thus, scientific survey data like the presented in this study are a key to address biodiversity and management issues.

Despite the relatively low percentage of flatfish in commercial landings, their importance on the functioning of the benthic-pelagic ecosystems is crucial. This role has been evaluated for both the Gulf of Nicoya and Golfo Dulce by means of trophic models that estimated the impact on the system of the removal or addition of the biomass of groups or organisms or of detritus (Wolff, Hartmann, & Koch. 1996; Wolff, Chavarría, Koch, & Vargas, 1998; Alms & Wolff, 2019; Sánchez-Jiménez, Fujitani, MacMillan,Schluter, & Wolff, 2019). The historical data presented in this study, together with the recent reduction in fishing pressure and bottom damage, provide a unique framework for a future evaluation of the status of flatfish populations on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica. Of relevance is the updating of the trophic models in view of the increasing impact of both coastal development and other environmental tensors.

Ethical statement: authors declare that they all agree with this publication and made significant contributions; that there is no conflict of interest of any kind; and that we followed all pertinent ethical and legal procedures and requirements. All financial sources are fully and clearly stated in the acknowledgements section. A signed document has been filed in the journal archives.

uBio

uBio