Introduction and objectives

English, despite not being the most spoken language in the world, is acknowledged as lingua franca, that is to say, it is used by several groups of people in order to communicate. Millions of people around the world are learning English, and Chile is not an exception. According to a study published in 2013 by EF EPI (Education First, English Proficiency Index), Chile is placed in the 41st position, classified as a low level of English country. Different governments and educational establishments have put their efforts on the teaching of this language. However, teachers in Chile encounter plenty of issues at the moment of teaching such as: crammed classrooms, lack of students’ motivation, and lack of planning time. Moreover, English language itself has difficulties when being taught; grammar, pronunciation, vocabulary, all of them have their own learning challenges. Among all these different issues, learning vocabulary is no doubt one of the most important. Vocabulary is as important as the main language skills of reading, writing, listening and speaking, since without the ability to recognize or produce a word of any kind, these language skills are virtually useless (Schmitt, 2000; Mehring, 2005).

In Chilean classrooms, vocabulary is not given the real importance that it should have, and this is shown by studies that revealed that 82% of Chilean students cannot understand English (Ramirez, 2013). Experts argue that Chile will never be bilingual if the 92% of students keep on attending public schools, which only offer 3 hours of English per week (De Améstica, 2013). Besides, EFL trainee teachers at universities start from a low level of English; consequently, to learn this language is a challenging task. Furthermore, most pre-service teachers tend to think that English has to mostly deal with Phonetics and Grammar; therefore, at the moment they start teaching English at schools, they end up focusing on grammar instead of teaching English as a means of communication (ChileGlobal, 2014).

This intervention consisted of applying a teaching approach that considers the use of comics as an authentic first source of language for learning new words. In this study, students from two different types of schools (public and semi-public) participated in a series of comic-based sessions called Vocabulary Through Comics, where key vocabulary was taught to students, then they read a comic, and finally, practiced by creating a comic strip using the words seen in the lesson. The main focus was that students, by using comics, could encounter new vocabulary in a communicative context. This paper is part of the research study FONDECYT 1150889 Las dimensiones cognitivas, afectivas y sociales del proceso de planificación de aula y su relación con los desempeños pedagógicos en estudiantes de práctica profesional y profesores nóveles de pedagogía en Inglés.

Theoretical framework

The concept of vocabulary

When talking about vocabulary, what firstly comes to our minds is words. They are an important part of language as they are used to understand others' ideas and express our thoughts. However, there are different perceptions about what vocabulary really is. According to Cambridge Dictionaries (2014), vocabulary is all the words that exist in a particular language. According to Hatch & Brown (1995), the term vocabulary refers to a list or set of words for a particular language or a list of words that individual language speakers use. Consequently, for the purpose of this research we would define vocabulary as all the words that exist in language, which are used by individual speakers in order to communicate.

Vocabulary acquisition

We already know the importance of vocabulary when learning a foreign language; however, how can we learn a word? Both students and teachers report that vocabulary acquisition is an essential part of first and second language learning (Duppenthaler, 2002); yet according to several authors (Folse, 2004; Walters, 2004; Hunt & Beglar, 2005), there has not been significant research conducted in this field. However, in the mid-1990s, there was a mini-explosion of research on this area, regarding second language vocabulary issues such as students’ needs, teaching techniques, learner strategies, and incidental learning (Folse, 2004).

Vocabulary acquisition depends on pedagogical actions in order for it to occur. By this we mean that teachers need to pay attention to different factors at the moment of teaching students new words. However, which aspects should teachers take into account when selecting strategies to teach vocabulary in the classroom? Coady (1997) proposes four main approaches to L2 vocabulary instruction: Context Alone, Strategy Instruction, Development plus Explicit Instruction, and Classroom Activities.

Context Alone "proposes that there is actually no need or even justification for direct vocabulary instruction" (Coady, 1997, p. 275).

Strategy Instruction "proposes the teaching of vocabulary learning strategies as an essential component of acquiring vocabulary" (Coady, 1997, p. 277).

Development plus Explicit Instruction "argues for explicit teaching of certain types of vocabulary using a large number of techniques and even direct memorization of certain highly frequent items" (Coady, 1997, pp. 278-9).

Classroom Activities, "advocates the teaching of vocabulary words along very traditional lines, these are best exemplified by a number of practical handbooks for teachers which contain generic activities for vocabulary learning to teachers" (Coady, 1997, pp.280-81).

These four approaches provide a useful tool for teachers who want students to learn vocabulary through direct acquisition. On the other hand, there are teachers who believe in indirect acquisition, which relies on the assumption that spelling and vocabulary are developed in second languages as they are in the first language (Krashen, 1989). This kind of vocabulary acquisition makes reading comprehension play the main role. However, in some languages in which the L1 is completely different from the L2 (Chinese, for example), it is a serious challenge for students to acquire vocabulary, and consequently, the target language (Haynes, 1990). Nonetheless, there is evidence in recent studies that affirm that a combined approach is superior to both direct and indirect alone (Zimmerman, 1994; Paribakth & Wesche, 1997). That is to say, vocabulary acquisition can happen in three ways: indirectly as a natural process when reading; directly, when students are taught the words they are going to learn; and combined, when students undergo both types of instructions, indirect and direct.

There are different strategies through which students are supposed to acquire vocabulary, for example, incidental and direct instruction; there are also certain characteristics that we cannot avoid when studying vocabulary and different situations that need to be undergone in order to acquire words. Many state that students need multiple high quality, contextualized and engaging examples of the words in use (Stahl & Fairbanks, 1986, Beck, Mckeown & Kucan 2002; Graves & Watts-Taffe, 2002; Mckeown & Beck, 2004). That is to say, students need to read and listen as much as they can when trying to acquire words as in receptive knowledge. Others (Watts-Taffe, Blachowicz & Fisher, 2009; Padak, Newton, Rasinki & Newton, 2008), during 20 years of research, add the importance of the active engagement of students. By the active engagement of students they mean the importance of exposure and exercises that foster an understanding of words and ways to learn them. As every student is different, each learner needs a different way of acquiring vocabulary. The quality of these different sources of new words may also come from varied contexts such as formal and informal texts.

There is an issue in which many authors agree, that is, repetition of words. It is an important process that students need to undergo in order to acquire vocabulary (Nation, 1990; Rott, 1999, Ghadirian, 2002). It has been stated that in order to remember a word, a learner needs among 5 to 16 repetitions and encounters for learning to occur (Salling, 1959; Saragi, Nation & Meister, 1978; Nation, 1990). Sökmen (1997) also agrees on the importance of repetition when acquiring a word; however, he adds that this repetition or retrieval is important for a word to be active, that is to say, it is not only necessary to recognize a word when reading or listening to it over and over but even more important is when students use it in writing or speaking.

Word knowledge

When talking about vocabulary we may refer to different aspects of word knowledge. However, what do we understand by word knowledge? We could simply define it as the knowledge of words. What does it mean to know a word? Here we approach different definitions or ideas proposed by important vocabulary researchers. According to Nation (2001) "in order to know a word, one needs to know the word's form (spoken form, written form, and word parts), meaning (meaning(s), concepts, associations), and use (grammatical function, collocations, constraints)" (p.27). That is to say, the learner needs to know everything about a word; however, this idea might refer to a language expert rather than a common person who wants to communicate through language. Some authors (Baumann, Kame'enui & Ash, 2003) define knowledge of words as depth of knowledge. Another definition we can talk about is vocabulary size, which refers to the number of words that a person knows (Read, 2000). An equivalent name suggested by a recent study for the previous definition is breadth of knowledge (Baumann, Kame'enui & Ash, 2003).

Other types of vocabulary knowledge classifications are the ones in which vocabulary is divided into receptive and productive (Nation, 2001). Receptive knowledge refers to words that learners recognize and understand when they occur in a context. It is a passive process because students receive ideas from others and make associations when reading or listening. As for, productive knowledge, it refers to words which learners understand, pronounce correctly and use constructively in speaking and writing. Therefore, productive vocabulary is an active process, because learners produce words to express their thoughts to others (Rodgers, 1987; Schmitt & McCharty, 1997; Nation, 2001).

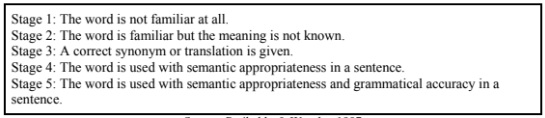

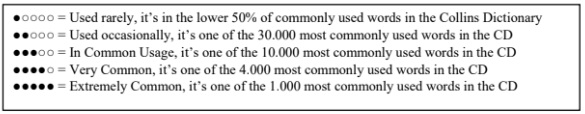

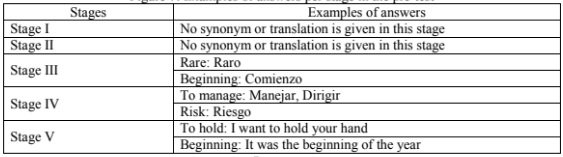

Considering the criteria given above, a vocabulary knowledge scale (VKS) was developed by Paribakht & Wesche (1997). It describes five stages in which vocabulary acquisition may occur.

This vocabulary knowledge scale might combine the characteristics of receptive and productive knowledge as in some stages students might recognize words in context but might not know how to use them, or recognize a word and know how to use it appropriately showing that they know its meaning, form and use. Despite some authors do not support vocabulary knowledge as something developed in different stages because it requires deep knowledge of words (Schmitt, 1998), there are others who tend to define vocabulary knowledge by using the developmental and dimensional approach (Read, 1997). Both approaches describe the acquisition and mastery of words through stages or levels associated with the word knowledge scale (Laufer, 1997; Nation, 2001). However, the developmental approach attempts to measure how vocabulary develops over time, and the dimensional approach measures which word knowledge types are known.

Visual influence

It is known that a word conveys more than a simple definition, but represents also an image. Therefore, presenting words accompanied by images could help learners to better understand the meaning of that word. “As far as vocabulary learning is concerned, pictorial cues will help learners make associations between pictures and words, and learning will be facilitated accordingly. Information would be, therefore, better remembered when it is dually rather than singly coded, because when one memory trace is lost, the other is accessible” (Sadeghi & Farzizadef, 2013, p. 4). Pictures are easily remembered by people, in comparison to words, as they activate the image-to-word referential connection. Hence, words are better remembered when associated with pictures (Milton, 2009). And, to make the visual influence on learning vocabulary clearer, Raimes (1983) states that pictures are not only helpful for learners, but also for teachers. Consequently, there will be a double benefit for teaching and learning vocabulary through the usage of images.

Reading influence

Reading is another important factor when acquiring vocabulary. There have been several investigations throughout past decades that support the belief about reading and indirect vocabulary learning (Saragi, Nation & Meister, 1978; Nagy, Anderson & Herman, 1987; Krashen, 2004). These studies found evidence that shows that children could learn vocabulary indirectly in context while reading. Krashen (1989) extends this claim to second language learning, explaining that reading will result in vocabulary acquisition. Krashen bases his claim on the input hypothesis. The input hypothesis affirms that second and foreign language is acquired by a focus on the message and not on the form of the message. Krashen (2004), in a recent study, explains that vocabulary is best developed through real encounters with the words in context, over time, and in small doses. That is to say, students need contextualized examples, which can make them feel part of a story, and not being taught words in isolation (Blachowicz & Fisher, 2009). Research not only suggests that reading is good for improving vocabulary, but also that reading stimulates the desire and ability to do self-selected reading (Wang & Lee, 2007).

Criteria for selecting vocabulary

Choosing words to teach is not simply a matter of assigning words. Evidence suggests that students need explicit instruction in word meanings, repeated exposure to words, opportunities for wide reading, and experiences using the words in the presence of their peers (Graves, 2006; Fisher, Blachowicz & Watts-Taffe, 2011). There are defined categories for words, which have become part of the lexicon for vocabulary researchers and teachers. These categories have guided teachers in the selection of words and facilitated an understanding of the value in learning different kinds of words. They are presented below.

Three tiers of words

Beck, McKeown & Kucan (2002) outlined a useful model for conceptualizing categories of words that readers encounter in texts and for understanding the instructional and learning challenges that words in each category present. They describe three levels, or tiers, of words in terms of the words’ frequency and applicability.

Tier 1: Common, known words: words are basic, and do not necessarily need instruction. These words are part of most children's vocabulary instruction. Example: book, girl, dog, orange.

Tier 2: High-frequency words: words include frequently occurring words that appear in various contexts and topics and play an important role in a variety of different content areas. Example: masterpiece, fortunate, measure.

Tier 3: Low-frequency, domain-specific words: words are domain specific vocabulary. Words in this category are low frequency, specialized words that appear in specific fields or content areas. Example: isotope, asphalt, crepe.

Considerations for selecting vocabulary words

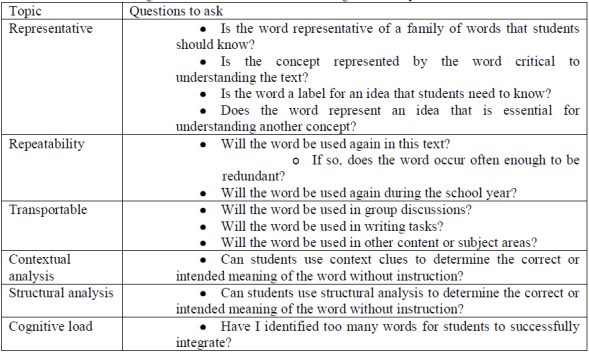

Fisher & Frey (2008) outlined different questions that need to be answered at the moment of selecting vocabulary so that teachers know if these words are worthy of being taught. This information is described in Figure 2.

Comics

Eisner (1985) put comic books under the concept of sequential art. Nevertheless, McCloud (1993) gave the most accurate definition for comics: they are juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer.

This sequential art has been present in mankind history. For example, the Rosetta Stone, a granodiorite stele which helped to understand Ancient Egyptian literature and civilization. The Codex Zouche-Nutall: a pre-Columbian picture manuscript1, which told the story of the great military and political hero Ocelot’s Claw and the Bayeux Tapestry, an embroidered cloth that depicts with images and words the events of the Norman conquest of England

From ancient cultures to the present, the use of images in a sequencing order to convey meaning and message has been present, evolving in a more sophisticated way including the use of words and graphic elements.

Comics in education

Nonetheless, one question arises when talking about this topic: can comics be used in education? The answer can only be positive, and history proves us that they have been used before. Comics are:

Adaptable: they can be used to teach literature, as in classic comics and its adaption of Robinson Crusoe (Sones, 1994).

Exciting and motivating: comics can excite and motivate reluctant readers, ESL students, and gifted students (Smiths & Wilhelm, 2002; Krashen 2004; Cary, 2004; Carter, 2007)

Beneficial: texts using visual scaffolds are beneficial for ESL students and struggling readers.

Comics can only bring us positive aspects when talking about vocabulary acquisition and as Cary (2004, p. 101) states "comics are an ideal vehicle for word study". Studies of the brain suggest that when verbal and visual information are presented together, more of the brain is activated than when it shows information only in one mode or another (Fisher & Frey, 2008). Comics cover a different range of topics, from humour to history, they also cover different kinds of vocabulary. Consequently, the present research on vocabulary acquisition proposes an intervention in which students learn vocabulary through intervention sessions based on comics so that they can acquire words in context and with the help of pictures.

Empirical studies on comics and vocabulary

According to a research study conducted by Wijaksana (2008) in Indonesia in order to encourage a group of students' motivation in improving their ability to speak English, it was shown that using comics through peer work as a teaching strategy, students increased their average scores and consequently, they improved their vocabulary ability significantly.

A research project conducted by Khoiriyah (2010) in Indonesia to two groups (Experimental and Control group) to learn English vocabulary, showed that there was a difference in the vocabulary score of students using comic stories and those who were taught using non-comic stories, being the experimental group the one with the highest average score. Besides, according to a research study conducted by Aziza (2012) in Indonesia to 65 students of a seventh grade divided into two groups (Experimental group and Control group), it was found that teaching vocabulary by using comics as media for increasing vocabulary mastery was significantly more effective than the one used in the Control group.

Sri Wilujeng (2014) in Indonesia to three groups used three different kinds of instructions (Collaborative learning, Comics, and Direct instruction) to learn Mandarin Chinese, the means between pre and post-tests were higher in the Collaborative learning group, followed by the Comic group, and at the end the Direct instruction group. Kurniyanti (2008) in Indonesia used Oliver Twist Comic Book as alternative material in teaching extensive reading, it was found that comic books as alternative material can bring some positive results, such as enriching vocabulary and grammar, developing new language and information about different cultures and stimulating creativity.

Furthermore, according to a research project conducted by Jones (2010) in Japan, the use of comic books and the participants' response to them support that contextual illustrations and context help to enable participants’ schema formation and general comprehension of text. This results in less reliance on distracting dictionary use and hence less split attention effect. Besides, the participants indicated that they enjoyed the experience of reading the comic books and were more motivated to read more comic books in English.

Research methodology

Type of study

This study follows action research, a type of methodology in which knowledge is built through practice (Sandín, 2003). Creswell (2005, p. 552) highlights the importance of this type of methodology as “it allows researchers to study local practices (community or group), it is centered on the participants' development and learning, and it implements an action plan in order to solve a problem, introduce an improvement, or make changes”.

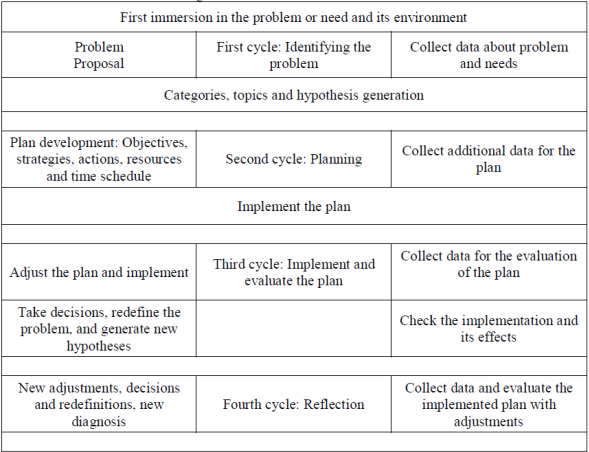

The action research model we follow is the one proposed by Sandin (2003) who explains it through cycles. These are:

Detecting the problem of the research, clarify and diagnose it (it can be a social problem, a need for a change, an improvement).

Planning the action in order to solve the problem or introduce the change.

Implementing the plan and evaluate results.

Reflect in order to give a new diagnosis.

This model can be illustrated in Figure 3:

Research objective

To determine 11th and 12th school students’ vocabulary performance before and after a didactic sequence based on comics.

Research hypothesis

There is statistically significant progress between the pre-test and post-test.

Research settings and participants

This research was carried out in two educational establishments, a semi-public school (Research group 1) in Talcahuano, Chile and a public school (Research group 2) in Concepción, Chile. The participants were eleventh and twelfth graders in both schools. Students attended as volunteers to an after-class workshop in which they were informed they were going to learn vocabulary through comics.

In the semi-public school, the class group consisted of seventeen students, four boys and thirteen girls. These students have had English lessons from pre-kindergarten, and have approximately had 1008 hours of English so far. In the public school, the class group consisted of ten students, all of them were girls. These students have had English lessons from fifth grade, and have approximately had 624 hours of English so far. Since this is a qualitative intervention-based study, the number of participants and their corresponding background knowledge in English do not affect the reliability of the findings. They are just characteristics of the context where this study was conducted. This is clearly not an quantitative experimental study.

Instrument

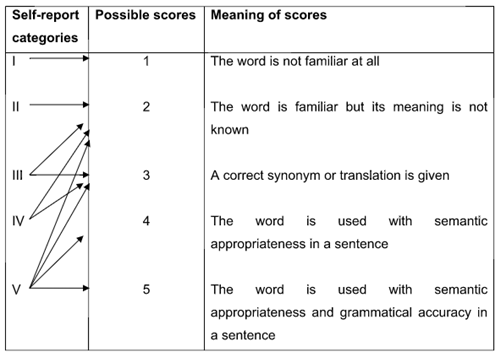

In order to gather the information needed for this study, we adapted the vocabulary knowledge scale proposed by Paribakht and Wesche (1993) as pre-test and post-test to identify students' knowledge of the words taught. Each word/question considers five scales as possible answers. Each answer has its own score, as shown in Figure 4:

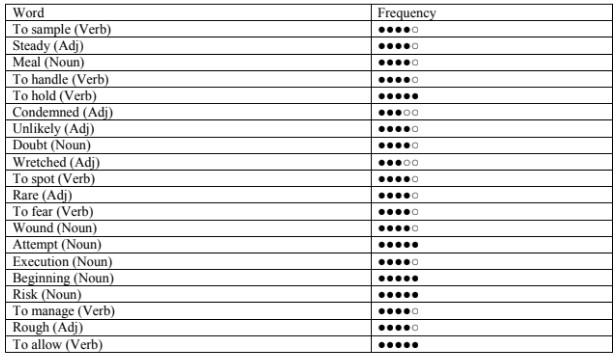

Throughout the intervention, forty words were taught; all of them were content words (nouns, verbs and adjectives). For the selection of words, we used different criteria, which were based on the three tiers previously explained (Beck, McKeown & Kucan, 2002), and the considerations for selecting vocabulary words proposed by Fisher & Frey (2008). Nevertheless, the pre-test and post-test considered twenty words for being evaluated. All of the words in both tests belonged to the tier 2, as they were high frequency words. In order to check the frequency of these words, the researchers looked the words up in Collins Dictionaries (2014), which base their data on the Collins Corpus and the Bank of English™. Regarding these sources, the frequency of words in Collins Dictionary is divided in five categories. This can be seen in Figure 5.

The list of words evaluated in pre-test and post-test can be seen in Figure 6, with their frequency respectively.

Intervention procedure

In this study, the research practitioners conducted five intervention sessions, in which students were taught vocabulary using comic-based instruction following the Presentation, Practice and Production approach to language teaching. In the first stage, words were introduced by showing students slideshow presentations which contained the word, a picture that portrayed the word, and a sentence related to the word so that students could see it in context. Afterwards, the comic was read out loud and students listened and paid attention to its written form and the pictures that showed the comic. Then, students read the comic in silence and asked teachers in case of any question regarding the vocabulary. In the second stage, students were given worksheets to work individually on the words presented and do commonly used classroom exercises such as multiple choice questions, matching, fill in the gaps, and sequencing. Besides, students collaboratively practiced the words in context through different games such as mimics and charades so as to see the words learned during the lesson more than six times. Finally, in the last stage, students in groups had to produce a short comic strip retelling the comic story or creating a new one using the words learned during each lesson through dialogues, conversation or descriptions of the different scenes

Data analysis techniques

To analyze the effectiveness of the teaching and learning process, the researchers conducted tests at the beginning and end of the research cycle. After conducting the tests, the researchers compared the student's vocabulary achievement in the pre-test and post-test in each school in order to identify whether there was or not improvement of students' vocabulary. Once the results were obtained, the researchers used the Wilcoxon test, which measured the students’ achievements between the pre and post-tests. The Wilcoxon test is a non-parametric statistical hypothesis test used to compare two related samples on a single sample to assess if their population mean ranks differ.

Results

Research group 1 (semi-public school)

In the pre-test in the research group I, answers were mainly found in Stage I or II, with a few exceptions in Stages III and V. These stages are the ones already mentioned in the vocabulary knowledge scale proposed by Paribakht and Wesche (1993). The results in the pre-test were according to what was expected, since students had not yet been exposed to the comic-based instruction, therefore, their body of knowledge of certain words was not sufficient to pass Stage II or higher. In the pre-test, researchers expected that students’ answers would be mainly found in Stages I and II, considering that a high percentage of words, if not all of them, are not included in the English national curriculum and, therefore, they are not taught at schools during the lessons. Some of the answers obtained in the pre-test in each stage can be seen in Figure 7.

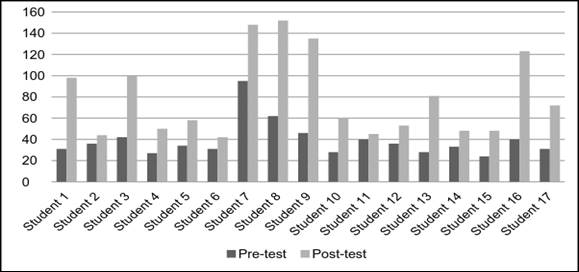

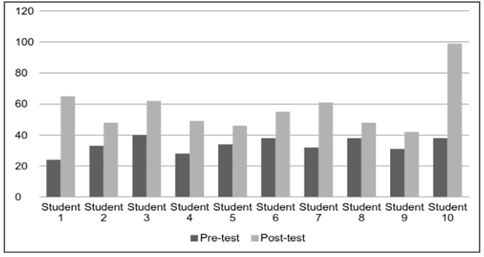

The results in the post-test in research group 1 were very dissimilar in comparison to the ones in the pre-test. Many of the taught words showed a remarkable improvement as most of them were placed in stages III and V. Consequently, the average scores showed also an improvement individually as well as in the group average. Individual scores can be seen in Figure 8:

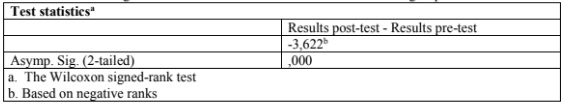

As can be seen, students achieved better scores during the post-test. Nonetheless, to prove if there was a statistically significant progress, we had to use the Wilcoxon test, which measures two related samples and aims to prove if there is progress in a vocabulary test given to a group of students from a semi-public school before and after a comic-based intervention. The progress was measured on a scale from 20 to 160 points. The research hypothesis for this specific objective is that students’ test scores improved after the comic-based intervention in comparison to the scores achieved in the pre-test.

In order to know if the students' progress was statistically significant, we have to observe the test statistics (Figure 8) and see if the Asymptotic significance (Asymp. Sig.) is lower than 0.05.

As Figure 9 shows, the Asymptotic Significance is equal to 0,000 (p < 0,05), therefore, we reject the null hypothesis; that is to say, there are differences between before and after the intervention. Then the students’ scores in the pre post tests are different and statistically significant.

Research group 2 (public school)

For the pre test in the research group 2, answers were mainly found in Stage I or II, with one exception in Stage III. Pre-testing results were the expected ones, considering that the pre-test was somehow a diagnostic test and students had not been exposed to the words before. The results in the post-test in research group 2 again showed an improvement, and most words were found in stages II, III and V, which proves that students were familiar with the words taught, and that they also knew their translations or how to use them in a sentence appropriately.

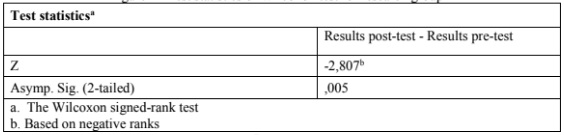

Although students from research group 2 did not get high scores as the other research group did, numerical evidence shows that at least there is progress. There is a slight progress if we compare the highest score from the pre-test and the lowest one from the post-test. However, to prove if there was a statistically significant progress, we had to use the Wilcoxon test, as was done with research group 1’s results, which tests two related samples. The research hypothesis for this research group is that the students' scores improve after the comic-based intervention in comparison to the scores achieved in the pre-test. In other words, there is a significant progress between the pre and post-test. In order to know if the students' progress was statistically significant, we have to observe if the Asymptotic significance (Asymp. Sig.) is lower than 0.05.

As Figure 11 shows, the Asymptotic Significance is equal to 0,005 (p < 0,05), therefore, the null hypothesis is rejected; that is to say, there are differences between before and after the comic-based intervention. It must be concluded that students’ scores in the pre and post tests are different and statistically significant.

Conclusions

The aim of this research was to establish students’ performance before and after a didactic sequence based on comics to learn vocabulary. According to the results of the pre and post tests, both research groups, 1 and 2, show a statistically significant progress on the knowledge of the words taught. Research group 1 (semi-public school) show the most remarkable improvement as they doubled their score (39,1*2= 78,2; 78,2 < 79,8) between the pre and post tests, but research group 2 (public school) was also close to double their scores. Nonetheless, the difference between the two groups and their final performance in the post tests may be due to the exposure to English they have had throughout the years (1008 in comparison to 685 hours). Although a comparison between the groups was not one of the objectives of the study, it is indeed an element to have it in mind for further research.

Therefore, we can conclude that our comic-based intervention was successful in teaching new vocabulary in two different contexts. The students’ progress, and the scores achieved maybe be due to various reasons. First of all, their exposure to the comic-based instruction was an appealing way to learn vocabulary. The intervention sessions based on the Presentation, Practice and Production approach to language teaching had multiple high quality, contextualized and engaging examples of the words in use, which helped students learn the vocabulary and, consequently, as shown, results were successful. This approach supported all the theory and strategies explained to acquire vocabulary. Students started seeing the words in isolation, with a visual cue, in a sentence, and, afterwards, they would read it in the comics, and later on during the individual and group activities. The visual influence played an important role in the results and learning. It was easier for students to remember words when they were associated with images or pictures (Milton, 2008). The sessions started with students looking at the visual representation of a word that was going to be learned. This helped students predict what was going to happen in the reading, and therefore, they were more engaged to participate as they already knew some vocabulary before reading. Another factor to be explained as an important tool for learning was the use of comics. If used as a reading resource, comics are a helpful and appealing tool to put the words in a real communicative context, when vocabulary is best developed (Krashen, 2004). Students not only knew some words before reading the comic, but also when reading it, they immediately had the opportunity to associate the word with another picture in an authentic context, in which they felt excited and motivated. As theory says, this is beneficial for ESL students and struggling readers. However, and talking about our contexts, this could also apply for EFL students in Chile thanks to comics’ adaptability.

Another important part of the lesson that played an important role was the activities done during the practice stage of the lesson. According to theory, students also need an active engagement during activities. Students were exposed to different kinds of input during the lessons, they not only worked with worksheets, but also played mimics, charades, and created their own comics so as to acquire the words during each lesson. These activities encouraged participation among students and, also, different ways to learn the vocabulary. This, according to theory, is very important to foster an understanding of the words.

Finally, the sequence of these lessons leads to another important factor for learning words: Repetition. Theory states that in order to remember a word people have to encounter it from five to sixteen times (Salling, 1959; Saragi, Nation & Meister, 1978; Nation, 1990). Consequently, as the Presentation, Practice and Production approach to language teaching supports this repetition because of the clear sequence of activities, students could see the words in different contexts, in isolation, with a visual cue, in sentences, in worksheets, during speaking activities (mimics, charades) and, finally, when creating the comics. Students did see the words more than five times, and, therefore, this helped them recall all the vocabulary, and consequently the results showed how students doubled their scores in general.

Further research

In this research, it was acknowledged the improvement of acquiring vocabulary through comics in two schools: a public and a semi-public. There is plenty of practical applications of this study. Future works can include the teaching of grammatical structures through this methodology. We already know that acquiring vocabulary through this method may be useful, but comics as a source of colorful heroes and heroines have a tremendous capacity to engage and motivate students, fire the imagination and bring additional fun elements to lessons. As this sequential art provides visual cues for readers, they can foster bringing stories alive and guiding them through narrative using different grammatical structures. We discovered that one of the most enjoyable and rewarding comic-related activities is for students to create their own comics, so making them create a comic strip using the grammatical structures learnt can be beneficial for them. Besides, making students write the comic strips of a story, and role-play them could foster their speaking skills. In a socio educational context such as the Chilean one, in which comics have barely been used inside the classroom, the inclusion of them as an educational resource allows teachers for an enriching innovation not only for English classes, but also for Literature and History lessons. When thinking about an inter-curriculum plan, the use of comic books brings the opportunity of connecting English with other subjects, making the language more realistic and real-life connected to the students’ environment.

Nota

1An accordion-folded pre-Columbian document of Mixtec pictography.

Ver Appendix