Introduction

Nowadays, sports teams use the amount of data available to their advantage. The sports industry uses sports analysis to improve player performance (Redwood-Brown et al., 2019), a team’s quality of play (Castellano & Pic, 2019), and win games (Collet, 2013), among other enhancements.

Football teams basically aim to achieve two major targets: scoring goals and preventing the opposing team from doing so. The repertoire of variables and indicators of both phases of the game, offensive and defensive, helps to describe the variables that can tell the difference between top, bottom, and middle teams (Varley et al., 2017), winners and losers (Collet, 2013; Hughes & Franks, 2005), or between two professional leagues from the same country (Castellano & Casamichana, 2015; Morgans et al., 2015).

Following the football analysis, some indicators (in addition to the goals scored) are used to measure offensive effectiveness, i.e., shots on goal, scoring chances, and final third pitch entries (Tenga et al., 2010). Also, passing and dribbling skills are important in the attack phase. About the 1990 FIFA World Cup, Hughes & Franks (2005) conclude that there are more goals scored from longer passing sequences than from shorter ones. Furthermore, the national teams make substantially more attempts on target per possession for these extended passing sequences, but the proportion of goals from shots is greater for "direct play" than for "possession play.'' In the 2014 FIFA World Cup, successful teams had high ball possession rates (Göral, 2015). In the Spanish League, better performance in technical-tactical actions produced in the offensive phase (shots, center kicks, corner kicks, total passes, and the ratio of successful passes) is found in the top teams (Castellano & Casamichana, 2015). Ball possession is a stronger factor to determinate top teams in the Greek league (Gómez et al., 2018), Spanish league (Castellano & Casamichana, 2015; Lago-Ballesteros et al., 2012), and English league (Morgans et al., 2015). However, Collet (2013) performed an analysis of ball possession and team success in European leagues and international tournaments held between 2007 and 2010, and he determined that in league matches, the effect of larger possession is consistently adverse; in the Champions League, it has nearly no impact; and in national team tournaments, possession fails to reach importance when attack factors are accounted for.

It has been studied the identification of goal-scoring characteristics and successful attacking styles in European leagues by way of comparison. Thus, Mitrotasios et al. (2019) compared, in the top four European football leagues, the goal-scoring opportunities. Their results reported some differences in the four leagues: La Liga was good at the combination of offensive methods; English Premier League showed a high degree of direct play; Italian Serie A showed the shortest offensive sequences; and Bundesliga had the greatest number of counter-attacks. Yi et al. (2019) also suggested Serie A players achieved lower numbers of ball touches, passes, and lower pass accuracy per match than players of the other four leagues in the UEFA Champions League tournament. Regarding Spanish La Liga, compared to other European leagues, Konefał et al. (2015) showed that the full-backs executed the highest number of passes and crosses and ball touches in the third pitch zone. They also performed the lowest number of passes in the midfield and defensive zones.

Because of the above, it would be interesting to know the style of play used by professional football teams in order to design the tasks with greater precision and optimize their performance. Coaches build up favorable contexts for their players, but the tactical options made by each player in a specific game situation can reveal the process of the match performance in football (Gómez et al., 2012). Football players have options whether to perform a penetrative (assist sometimes) or non-penetrative pass each time they win or receive a ball during a match. Deep passes have been found to be more effective than non-deep passes in producing goals and shooting chances regardless of the defensive situations played (Tenga et al., 2010). In this sense, it is also important to keep in mind that the performance analysis of the opponent’s interaction in developing the technical skills is one of the key features of the logic of football (Tenga et al., 2017).

The dominant migrants outside the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) confederation originate from South America and Africa (Littlewood et al., 2011). Nevertheless, most previously mentioned variables have been verified in the most valued domestic European tournaments that have their own tactical conceptions and playing styles. For this reason, more studies are needed to fully assess the impact of tactical and technical variables in the best South American leagues. Only Arruda-Moura et al. (2012) showed Brazilian teams' spread on the pitch while defending and attacking for the purpose of researching the teams' organization in the tackle and shot on target chances.

The impact of cultural features across different continents and tactical elements on football performance has not been extensively researched. Thus, exploring the offensive styles and efficiency in some of the world's most renowned and valued competitions could offer much-needed information for player agents, scouts, referees, and, of course, coaches and scientists to improve team preparation. Furthermore, comprehending how contextual aspects influence performance could enhance the quality of research in match analysis (Mackenzie & Cushion, 2013).

Because of the lack of related studies and the presence of unclear results, the main purpose of the present study is to compare the teams’ styles of attack in European and South American elite football in the two most valued domestic leagues in both continents during the season 2019/2020. More specifically, we hypothesized that an objective provision of data from different leagues would help identify differences and similarities of the offensive process between continents.

Methods

Sample

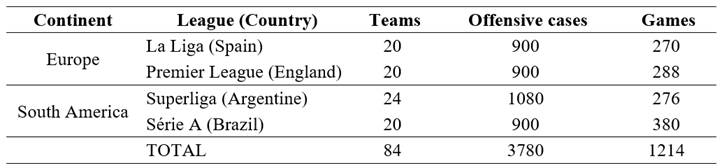

The sample included 3,780 offensive activities from 84 teams participating in 1,214 games during the 2019/2020 season. Demographic data are shown in Table 1. Data were taken until the interruption of the sport competitions due to Covid-19 in March 2020. All teams and the total of the played games in each league were included for comprehensive analysis. This study was not subject to specific authorization by any ethics committee of the institutions involved. There were collected data that did not require any formal approval by any institution. However, the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

According to UEFA (2019), the most scored leagues in Europe are Spanish La Liga and English Premier League, just as Argentinian Superliga and Brazilian Série A are in South America top 3 according to IFFHS ranking (2019).

Procedures

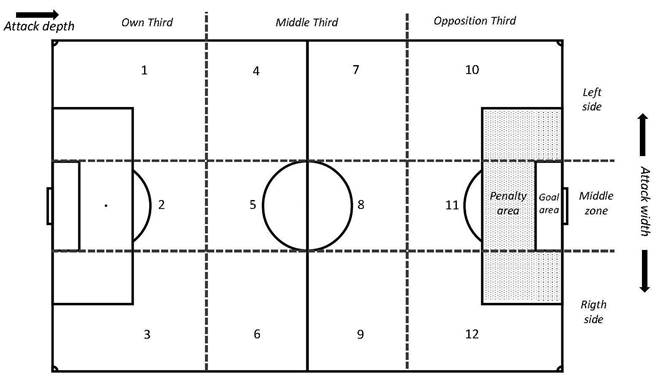

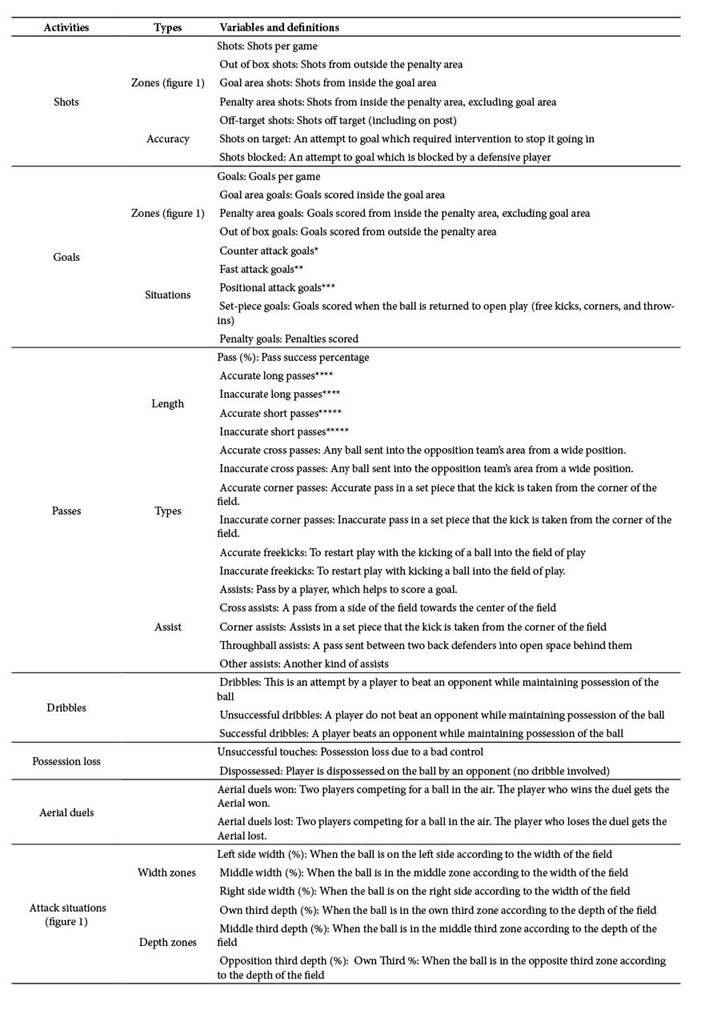

According to Sarmento et al. (2010), data were collected manually using a specific notation system designed to perform the analysis. The observational tool combined launch zones and key offensive activities (Table 2) were subcategorized into (a) shots, (b) goals, (c) passes, (d) dribbles, (e) possession loss, (f) aerial duels, (g) attack situations, and (h) spatial area of the field (Sarmento et al., 2018; Sainz de Baranda et al., 2019) (Figure 1).

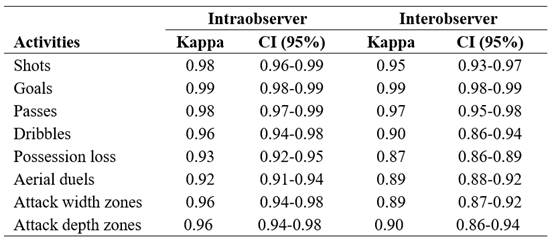

Twelve analysts experienced in match analysis procedures used this specific observational instrument tool to analyze offensive sequences. Each analyst had analyzed >100 football games using this method. Interobserver reliability was estimated using 2 analysts (Sarmento et al., 2018) who both coded 480 offensive cases (corresponding to 12.7% of the sample) randomly selected. Intraobserver reliability was ending using the same offensive cases, but 1 analyst repeated these on one occasion (after a 3-week period). Intraobserver and interobserver agreement (Table 3) was assessed using Cohen’s Kappa (Cohen, 1960): high level of reliability (Kappa values > 0.90).

Table 2 Descriptions of variables and definitions of category. Mean and percentage (%) per game

* Counterattack- transition quickly between defense and attack when a team wins possession, using a degree of imbalance from start to the end of the attack towards the finishing zone (less than 12 s). All types of passes take place more in depth than in width. Reduced number of passes (5 or less) And also the number of players touching the ball directly (usually, 4 or less) (Sarmento et al., 2018).

** Fast attack-short and quick passes are performed both in width and depth. Maximum of 7 passes. The maximum sequence time of the attack is 18 s. A maximum of 6 players have direct intervention in the attack. (Sarmento et al., 2018).

*** Positional attack-when a team wins possession, it progresses without using a degree of imbalance. Passes occur more in width than in depth, mainly with short passes. A large number of passes (8 or more). The duration of the offensive sequence is higher than 18 s. A large number of players touch the ball in the attack (more than 6) (ATenga et al., 2010).

**** Long pass-when a player performs a pass that crosses 2 contiguous zones and is played in a third zone (Figure 1) to one of the teammates.

***** Short pass-when a player performed a pass within the same zone or one of the contiguous zones (Figure 1) to one of the teammates.

Analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed to obtain averages and standard deviations. All analyses were performed using a custom-made spreadsheet (Hopkins, 2007). The data were log-transformed to be analyzed in order to reduce the influence derived from non-uniformity error and then analyzed for practical significance using magnitude-based inferences (Hopkins et al., 2009). Practical significance was assessed by calculating Cohen’s d effect size (Cohen, 1988). Effect sizes (ES) between 0.2, 0.2-0.6, 0.6-1.2, 1.2-2.0, and 2.0-4.0 were considered as trivial, small, moderate, large, and very large, respectively (Hopkins et al., 2009). Probabilities were also calculated to establish whether the true (unknown) differences were lower, similar, or higher than the smallest worthwhile difference or change [using standardized difference (0.2) and its 90% confidence limits (CL), based on Cohen’s effect size principle]. A qualitative assessment of the magnitude of change was also included. Quantitative changes of higher or lower differences were evaluated qualitatively as follows: <1%, almost certainly not; 1-5%, very unlikely; 5-25%, unlikely; 25-75%, possibly/possibly not; 75-95%, likely; 95-99%, very likely; >99%, almost certain. If the 90% confidence limits (CL) overlapped, indicating smaller positive and negative values, the magnitude of the correlation was termed ''unclear''; otherwise, it was deemed as the observed magnitude.

Results

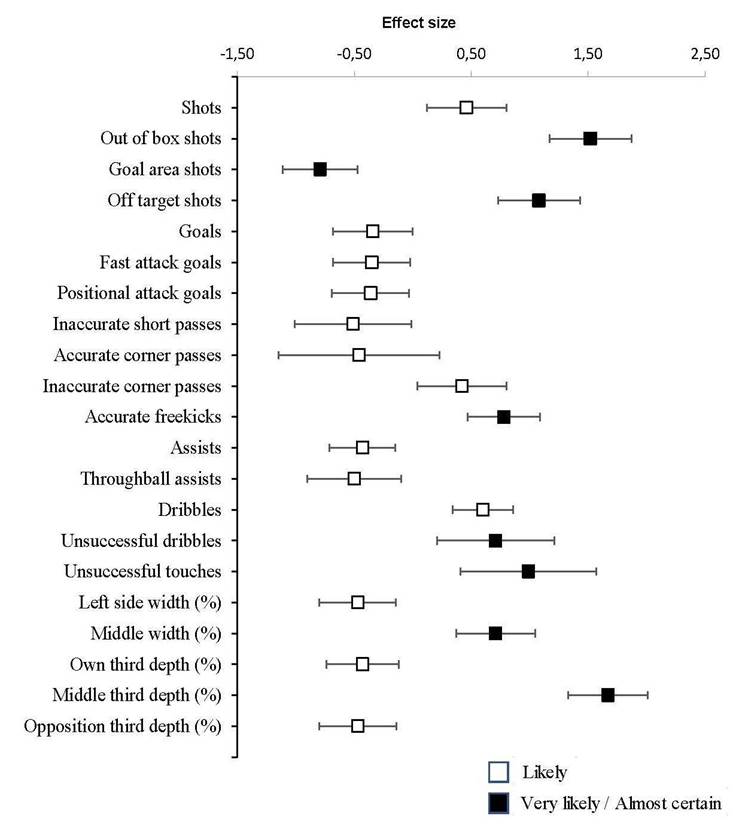

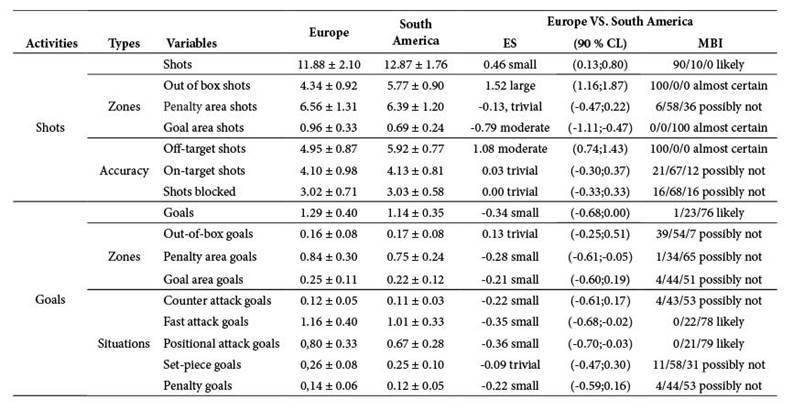

The results presented in Table 4 show a comparison between continents on shots and goals. Data points show significant differences in out-of-box shots and in off-target shots. It is also noteworthy that penalty area shots and on-target shots did not show significant differences between continents. The number of fast attack goals and positional attack goals in European teams was clearly higher than those of South American teams. In addition, there were no clear differences ascertained in goals out of box goals, goal area goals, and in counter-attack goals between the two continents.

Table 4 Differences in continents outcome according to shots per game, shots zone, shots accuracy, and shots body parts (mean ±SD).

ES = effect size; CL = confidence limits; MBI = Magnitude-based Inference

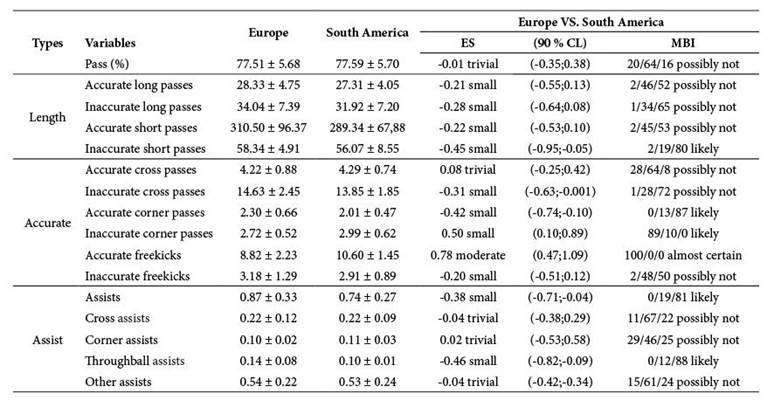

As for the variables related to the type of passes, Table 5 reveals meaningful differences in inaccurate passes, noting that European teams achieved a lower percentage than South American teams. In addition, it was observed that European teams achieved a higher percentage of assists and throughball assists.

Table 5 Differences in leagues outcome according to passes: percentage of possession and success pass, passes length, accurate passes, and assists (mean ±SD).

ES = effect size; CL = confidence limits; MBI = Magnitude-based Inference

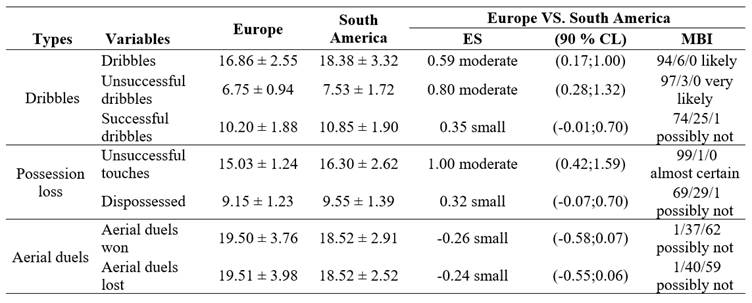

Concerning the variables related to dribbles, possession loss, and aerial duels, Table 6 shows that South American teams performed higher numbers of dribbles and unsuccessful dribbles per game. Teams from South America had a greater number of unsuccessful touches compared to the teams from Europe. Furthermore, no differences were observed in aerial duels.

Table 6 Differences in leagues outcome according to dribbles, possession loss, and aerial duels (mean ±SD).

ES = effect size; CL = confidence limits; MBI = Magnitude-based Inference

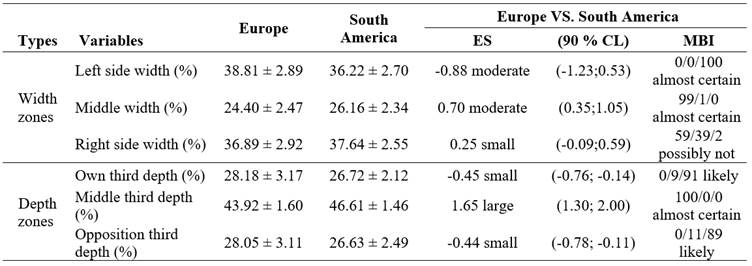

The width and depth action zones presented in Table 7 show substantial differences between continents. On the one hand, European teams’ attacks occur more often in the left side width; while on the other hand, South American teams use the middle of the pitch to do the same. In addition, South American teams spend more time in depth play zones in the middle of the pitch.

Table 7 Differences in leagues outcome according to attack situations: width and depth action zones (mean ±SD).

Focus on those variables that reached the highest significant values, the estimated true effects (effect size ± 90% confidence interval) of differences within pairwise comparisons between continents are shown in Figure 2.

Discussion

The purpose of the current investigation was to compare technical skills and tactical factors in relation to offensive play style in two continents, analyzing the two major European and South American Football leagues. As predicted, the main findings confirm the existence of differences and similarities between continents related to technical performance and attack situations. Differences were mainly focused on the variables related to goals, assists, and attack depth style, whereas differences in variables were related to set-pieces goals (ES = trivial), length passing, and aerial duels were minimal (ES = small). Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that analyzes technical skills and attack situations in football in top leagues from two continents.

Previous research explored some factors in isolation and only investigated a single league (Brito et al., 2019; Lago-Ballesteros et al., 2012; Tenga et al., 2010a; 2010b) or a single continent (Liu et al., 2015; Sarmento et al., 2018; Yi et al., 2019). The findings from this study show a slight contrast with prior research due to the different methods of analysis used (software for video match analysis, statistical analysis, notation systems…) and the data sources (official websites of the leagues or the clubs, free football data, professional platforms for analysis…). Therefore, this study offers some knowledge relevant for coaches, player agents, scouts, and sports scientists, as it enables some comparison and difference to occur and be applied in teams from elite leagues in Europe and South America.

Our research shows that teams from La Liga (Spain) and the Premier League (England) performed comparable match actions, and no considerable differences were observed across technical variables. In this sense, Yi et al. (2019) proved that the differences in technical performance between the top five leagues in Europe were minimal. However, other research (Oberstone, 2011) has suggested that teams from La Liga carried out a more elaborated and skilled playing style, while teams from the Premier League implemented a direct playing style, with moderately more tackles and aerial duels, and they cover larger distances in sprints. In addition, Oberstone (2011) detected relevant differences between La Liga and the Premier League associated with variables in defending and goal scoring. In this context, we have realized that South American leagues would have received relatively less attention in current research and consequently offer a new field of exploration.

There are differences in relation to the profile and mode of acting of coaches on the organization of training tasks (Gamonales et al., 2019). However, it is very usual that coaches instruct their players to organize the positions on the field according to their tactical choices during the training process. Fast attacks are the most effective ones regarding the effectiveness of offensive sequences (Sarmento et al., 2018). Our results show that European teams score a higher number of goals in fast attack situations than South American teams (ES = 0.35; likely MBI). The sequence time in a fast attack takes a maximum of 18 s (Sarmento et al., 2018) so the players should have good technical skills and ball control, dribbling, passing accuracy, assist skill, and other additional tactical skills based on game intelligence.

Our tactical-attack situations findings revealed, in width and in their depth game styles, that La Liga and Premier League teams do not share a similar style with Superliga and Série A teams. In the middle of the pitch and left side attack, the mean obtained is higher in the European teams. In addition, in depth play zones, the mean obtained in the middle of the pitch is higher in South American teams but lower in opposition third depth. The final third or attacking third refers to the area in and around the opposite team's penalty box (the 19-27 meters around the penalty box). This part of the field is the most successful area to score goals (Smith & Lyons, 2017), where most football matches are won or lost. In this zone of the pitch, the density of defenders is higher than any other, the reason why the good technical level of the attacking players is decisive. In this line, a previous study observed how top-ranked teams had a higher number of entry passes in the final third than the bottom teams (Yang et al., 2018).

A pass sent between two back defenders and out of the reach of the goalkeeper and further takes place in the opposite third zone of the pitch is called through-pass in football. It takes a great deal of skill and technical accuracy. Our results showed higher performance in this skill in Europe than in South America teams, thus demonstrating the highest technical performance. In contrast, South American teams played more in the middle of the field, which is associated with greater passing accuracy (Redwood-Brown et al., 2019), but it is not decisive for scoring a goal.

These findings may reveal technical performance differences (i.e., assists and through-ball assists or less unsuccessful dribbles and possession loss by unsuccessful touches) between leagues, probably due to growing levels of the best players and coach’s migration within Europe (Littlewood et al., 2011; Maguire & Pearton, 2000; Sarmento et al., 2013) and from South America to Europe (de Vasconcellos & Dimeo, 2009). Hence, in the top leagues of South America, the teams’ style of play and players’ technical characteristics need to evolve and assimilate (de Vasconcellos & Dimeo, 2009; Maguire & Pearton, 2000). The diversity of tactics and strategies enables teams to find an offensive tactic that could be suitable for their playing style in the attack.

Differences and likenesses have been identified in offensive performance for teams from each continent league. Technical and attack style profiles could be identified to provide a more comprehensive understanding for people involved in talent identification, player development, player recruitment, and coaches. However, limitations of this study should be noted, as it only compared the performance of the teams belonging to the two most valuables leagues played in Europe and South America rather than a greater number of leagues of each continent (for instance, Italian, German, Portuguese or Russian leagues in Europe; or Uruguayan, Colombian or Chilean leagues in South America). Therefore, the leagues teams’ features from a given continent recognized in this study may be relatively small given the general characteristics of that entire continent. Due to the globalization of transfer markets, further studies should account for the sample used and extend it to other leagues and continents. Lastly, it would be advisable to analyze the game models based on the competitive month since, throughout the league, coaches are modifying their styles of play. It may happen that authoritarian coaches tend to use defensive styles compared to coaches with methodology based on offensive styles.

Conclusions

European teams scored more goals per game than teams from South America in fast and positional attacks. In addition, European teams spent more time playing in the opposition third zone of the pitch and performed a higher number of assists and through-ball assists per match than South American teams. No differences were identified in other variables related to set-pieces goals, length passing, and aerial duels.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.