Botany in Brazil at the turn of the 20th century

The development of a national botanical science in Brazil began with the foundation of the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden (JBRJ), created after the Portuguese Royal Family established itself in Brazil. It opened its doors to the public in 1808.

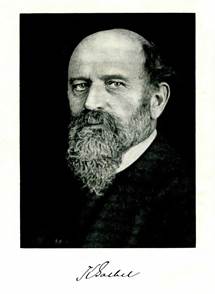

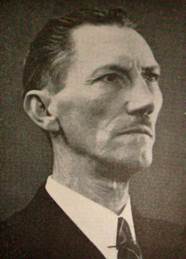

After periods of growth and others of complete neglect, botanical science in Brazil was given a renewed impulse by the new government after the military coup of 1889 overthrew the Empire of Brazil and established the first Brazilian Republic. Fundamental to this development was João Barbosa Rodrigues (1842- 1909), who took over as Director of the Garden in 1890, a position he held until his death (Fig. 1).

During his term of almost 20 years, Barbosa Rodrigues propelled scientific research of the institu- tion and he created the herbarium and the library, while also reorganizing the greenhouse, the nurseries and the Botanical Museum. Special attention was paid to the study of the Brazilian flora in its natural habitat. To this end, he created the position of naturalista viajante (‘travelling naturalist’) and improved the exchange with other scientific institutions. At the same time, and because of Barbosa Rodrigues’ predilection for the Orchidaceae, the Botanical Garden of Rio de Janeiro became the most important orchid research center in tropical America. The main avenue of the garden, lined with rows of royal palms that in some cases date back to King Dom João in 1808, was restored under Barbosa Rodrigues’ direction and is today one of the garden’s main attractions (Fig. 2).

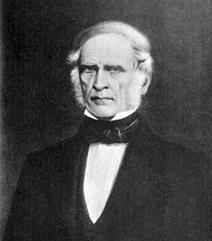

Dr. Antonio Pacheco Leâo (1872-1931) (Fig. 3) succeded Barbosa Rodriguez and directed the Botanical Garden of Rio from 1912 until his death in 1931: this was during the better part of Rudolf Schlechter’s involvement with Brazilian orchids (Alves Machado 1964: 133).

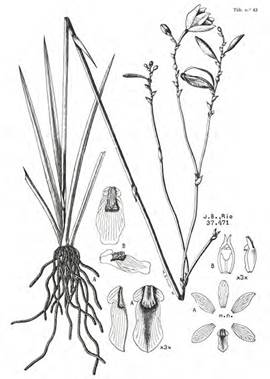

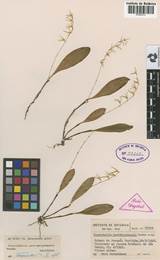

Paulo Campos Porto and Rudolf Schlechter named the new orchid genus Leaoa in his honor, transferring Hexadesmia monophylla Rodr. and proposing the new combination Leaoa monophylla (Rodr.) Schlechter & Campos Porto [= Scaphyglottis livida (Lindl.) Schltr.] (Fig. 4).

Other botanists who would play an important role in the history of Brazilian orchidology began their careers through a direct or indirect relationship with the Garden. Paulo Campos Porto (1889-1961), grandson of Barbosa Rodrigues, and one of the main actors in our story, became a traveler naturalist of the Garden in 1914. Years later, in the periods between 1933 and 1938, and 1951 to 1958, he would occupy the same position as his grandfather: Director of the Botanical Garden.

Figure 1 Bust of João Barbosa Rodrigues by Halley Pacheco de Oliveira, at the Botanical Garden in Rio de Janeiro.

Frederico Carlos Hoehne (1882-1959), a Brazilian botanist and ecologist of German origin, dedicated his life to the protection of nature in his country. In 1907 he became head gardener of the National Museum of Rio de Janeiro and from 1908 took part in several botanical expeditions through the interior of Brazil. Hoehne moved to São Paulo in 1917, where he became director of the Botanical Section of the Instituto Butantan. Established in 1901 in the district of Butantã, the Institute soon became one of the main scientific centers in Brazil (Fig. 5).

Although perhaps better known for its fundamental contributions to the development of antivenoms and medicines against many diseases, the botanical section of the Institute published a large number of new Brazilian orchid species in the Anexos das Memórias do Instituto de Butantan. Hoehne and Schlechter named Habenaria butantanensis (=Habenaria balansae Cogn.) (Fig. 6) and Pleurothallis butantanensis [=Acianthera saundersiana (Rchb.f.) Pridgeon & M.W. Chase] (Fig. 7) in honor of the Institute.

Finally, Alexander Curt Brade (1881-1971) moved from Costa Rica to Brazil in 1910. Because of his great interest in Brazilian orchids, he moved to Rio de Janeiro after World War I, where he worked at the Botanical Garden. He was appointed Acting Superintendent in 1934 and ultimately became Head of the Systemic Botany Department.

At the same time a number of private and public initiatives resulted in botanical expeditions to explore Brazil’s immense territory. Knowledge about the flora of Brazil, including the Orchidaceae, grew rapidly. Worthy of note are the ethnographic expedition of Dr. Hermann Meyer to Mattogrosso, with the participation of Robert Pilger (1876-1953) as leading botanist, and the collecting journeys of the Swede Per Karl Haljmar Dusén (1855-1926) in Rio de Janeiro and its environs (1901-1904) and in the province of Paraná (1908-1916). Other contributors to Brazilian orchidology were private collectors and European nurseries who imported plants from Brazil. Many of these palnts were sent to the Botanical Garden and Museum in Berlin for determination.

When Schlechter was engaged by Robert Pilger to determine his first Brazilian orchids, collected during the Meyer expedition to Mattogrosso, he probably was already aware of the immense richness of the Brazilian orchid flora. But even in his most optimistic moments he could not have dreamed that he would - over the next 25 years - describe a total of 13 new genera and over 350 new species.

In the following pages, as well as in future chapters referring to other South American countries, we will present short biographical notes of the most important botanists, plant collectors and orchid growers, a ‘network’ that over the years supplied Rudolf Schlechter with the material from which he made his most important discoveries. Some plant collectors have been left out, either because their contributions were of minor importance or because there is little information about their lives and work. Among the orchid growers, only those will be presented who not only imported plants from Brazil but actually visited the country.

It should not surprise us that the majority of these botanists and collectors were German or of German origin. After the foundation of the Second German Reich in 1861 under Emperor Wilhelm I and his Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, imperial ambitions arose in Germany. The Reich acquired a group of colonies in Africa and the Pacific. The new colonies in Africa were German South West Africa (Namibia and parts of Botswana), German West Africa (Kamerun and Togo) and German East Africa (Tanganyika, Ruanda- Urundi and parts of Kenya and Mozambique). In Asia the Empire acquired the colonies that received the names of German New Guinea and German Samoa. German botanists - among them Rudolf Schlechter - took advantage of this situation and took part in scientific expeditions that were organized to explore the richness of the new lands.

On the other side of the Atlantic, a number of German colonies had been founded in Brazil in the second half of the 19th century. Worthy of mention are,Nova Friburgo, the earliest (established in 1824 in the state of Rio de Janeiro) (Fig 8A), Blumenau (establ. 1850 on the River Atajaí-Açu, state of Sta. Catharina) (Fig. 8B), Doña Franzisca (establ. 1851, state of Sta. Catharina), and Brusque (establ. in 1867 as Colônia Itajahy, state of Sta. Catharina). Lepanthes blumenavii Barb.Rodr. (Fig. 9A) and Stenorrhynchos novofriburgensis (Barb.Rodr.) Barb.Rodr. (Fig. 9B) were dedicated to the two former colonies. Neu- Württemberg (Fig. 10) was founded in 1899 by the German Hermann Meyer in the state of Rio Grande do Sul and directed between 1903 and 1907 by his cousin Alfred Julius Bornmüller.

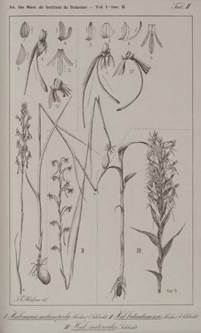

Figure 9 A. Stenorrhynchos novofriburgensis Rchb.f. (as S. hypnophylum). B. Lepanthes blumenavii In Martius, Eichler & Urban, Flora brasiliensis, 1896, 3(4), plates 37 and 103, respectively.

These colonies often became the destination of German botanists and plant collectors and are frequently named as localities of collection for numerous orchid species. It is therefore easy to understand -if for no other reason than national affinity- that during the first decades of the 20th century, Rudolf Schlechter received from German botanists visiting Brazil or residents of the country of German origin the largest collections of specimens of Orchidaceae to be determined. In addition, it must be repeated that after Schlechter’s return from his long expeditions to Africa and South East Asia he had already earned a reputation as one of the world’s leading orchidologists.

For the purposes of this chapter, we have divided the immense Brazilian territory into three large regions, corresponding approximately to the basin of the Rio de la Plata, the Amazon River basin, and the so-called Northeast region (territories along the Atlantic coast, between the state of Espirito Santo and the mouth of the Amazon). The first two of these were explored by an important number of naturalists; the third, however, was largely neglected.

The La Plata River basin

Draining approximately 17 percent of the surface area of the South American continent,-comprising almost all the southern part of Brazil, the south-eastern part of Bolivia, a large part of Uruguay, the whole of Paraguay and an extensive part of northern Argentina- into the South-western Atlantic Ocean, the la Plata River system (Fig. 11) is one of the most important river basins of the world.

The La Plata basin rivals the better-known Amazon River system in terms of its biological and habitat diversity and is formed by three large river systems: the Paraná, the Paraguay and the Uruguay.

In its Brazilian portion, the La Plata Basin extends through the states of Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catharina, Parana, Sâo Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Espirito Santo, the southern regions of Minas Gerais, Goias and Matto Grosso, and Matto Grosso do Sul.

A dozen - mostly German, or German-Brazilian - explorers began arriving in the southern states of Brazil in the 1880s. They would become the most important source of new orchids that would be described some years later by R. Schlechter. The Swede Per Karl Halmar Dusen and the Brazilians Paulo Campos Porto and João Dutra would be the only non-Germans (from origin or language) in Schlechter’s Brazilian network.

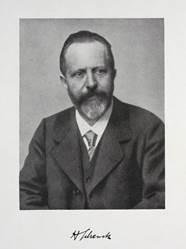

Johann Heinrich Rudolf Schenck (1860-1927; collected 1886-1887)

A German botanist, native of the city of Siegen, Johann Heinrich Rudolf Schenck (Fig. 12) was a brother of the well-known geographer Adolf Schenck. He began studying natural sciences at the University of Bonn and then continued his studies in Berlin under August Wilhelm Eichler and Simon Schwendener. He would later return to Bonn as a student of Eduard Strasburger, receiving his doctorate in 1884. In 1886-87 he accompanied Andreas Franz Wilhelm Schimper (1856-1901) on a scientific expedition to Brazil. After his return to Germany, he became a lecturer in Bonn, before being appointed director of the botanical garden at the Polytechnic Institute of Darmstadt in 1896. A few years later, between 1908 and 1909, he traveled to Mexico making important botanical collections. With George Karsten (1863-1937), he was co- author of the botanical journal Vegetationsbilder (Images of nature) (Karsten & Schenck 1904).

On their excursion to the tropics, Schimper and Schenck could not at first decide wether to go to Brazil or Cameroon. Considering the dangers of the expedition, Schimper - citing Grisebach - wrote to Schenck in 1885: “How general the perniciousness of climate may be follows from the fact that by far most scientific travellers in the most diverse landscapes become carried away with the experience, but in the tropical lands, almost without exception, well-known scientists are happy to return home. To die for science is, to be sure, no less ‘dulce et decorum’ than ‘pro patria mori’, but I wish not merely by my death, but also by my work, to earn a name for myself in the history of science” (Cittadino 1990: 104) . One understands that a decision was made to travel to Brazil.

The day before their departure, Schimper wrote to Daniel Coit Gilman, President of Johns Hopkins University: “I shall leave Bonn tomorrow for a short trip to Brazil. My leave of absence being a short one, I shall not be able to spent more than three or four months in the great South American Empire, the richest country in the world for a botanist” (Cittadino 1990: 105) .

Schimper and Schenck left for Brazil in August 1886, arriving in September at the house of Fritz Müller in the German colony of Blumenau in the state of Santa Catharina, on Brazil’s southeastern coast. Müller, an expatriate naturalist, had been living in Brazil since 1852 and was one of the earliest German proponents of Darwinism. Schimper returned to Germany in mid- December, but Schenck stayed behind and visited a number of sites in Brazil before he too returned in July of 1887. It was Schenck’s first and only excursion to the humid tropics.

In the Flora Brasiliensis of Martius, Engler and Urban (1896), Cogniaux mentions dozens of specimens of Orchidaceae collected by Schenck during his excursions with Schimper.From Schenck’s collections in Brazil, Cogniaux described and named in his honor Habenaria schenckii (Fig. 13), Pogoniopsis schenckii (Fig. 14) and Cryptophoranthus schenckii Cogn. [= Zootrophion atropurpureum (Lindl.) Luer]. In addition, Schlechter described and dedicated to him Stelis schenckii Schltr. (Fig. 15).

Schenck was known for his co-authorship, together with Ludwig Jost and Georg Karsten, of Eduard Strasbruger’s Lehrbuch der Botanik für Hochschulen (Text Book of Botany for High Schools), published in1894, that was used until the second half of the 20th century. When Schenck died in 1927 the book was in its 16th edition. One of its illustrations was of Vanilla planifolia (Fig. 16).

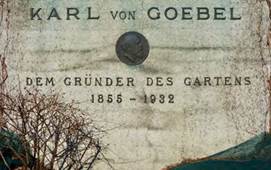

Karl Immanuel Eberhard Ritter Voon Goebel (1855-1932; collected 1890-91, 1913)

A German botanist whose main fields of study were comparative functional anatomy, morphology, and the developmental physiology of plants, Karl Immanuel Eberhard Ritter von Goebel (Fig. 17) began in 1873 studies of theology and philosophy at the University of Tübingen. It was the start of a brilliant career, which brought him to Strasbourg in 1876 to work with Anton de Bary. He took his Ph.D. from the university there in 1877. After three years of lecturing at the University of Würzburg, Goebel returned to Strasbourg in 1881 and went to Rostock in 1882, where he founded the botanical garden and a botanical institute. He moved again, this time to the University of Marburg as professor (1887-1891). He finally settled in Munich, where he would spend the rest of his life (Bower 1933).

While at the University of Munich, Goebel founded the Botanical Garden in Münich-Nymphenburg and served as its first director (Fig. 18).

Goebel was editor of Flora - the scientific botanical journal with the longest uninterrupted publication sequence (since 1818) - from 1889 onwards. In 1892 he became a member, and was later elected President, of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences; he was also elected a member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, the Royal Society of London and the Accademia Nazional dei Lincei in Rome. In 1931 he was awarded the Linnean Medal of the Linnean Society of London.

Karl von Goebel undertook his first research trip to Ceylon and Java in 1885-1886, before going to South America for the first time in 1890-1891, where he explored Venezuela and then British Guiana. Years later, in 1913, he went on a holiday to Brazil in the company of his fellow botanist Wilhelm Benecke. There, over several months, he explored the surroundings of Rio de Janeiro and the Organ Mountains. The orchids collected during these excursions were sent for determination to Schlechter, who described amongst them a new species, Epidendrum goebeli Schltr. (Fig. 15). Another specimen of Orchidaceae collected by Goebel was described by Kupper and Kraenzlin as Laelia goebeliana (Renner 1955) (Fig. 19).

The plant family, Goebeliellaceae Verd., and the genus Goebeliella Steph. were named in Goebel’s honor.

Karl Ritter von Goebel was a determined follower of the principles of organography, a scientific study that considered the parts of plants as “organs” and began to consider the relationship between different organs and different functions. His major work was published between 1898 and 1901 under the title of Organographie der Pflanzen (Organography of plants); it became an important reference work during the following decades. In it Goebel took some distance from the Darwinian theory of evolution. In a supplement to his work he wrote: “Two extreme aspects of biological science may be distinguished, and they are often pursued with but slight relation one to the other, viz., the morphological which concentrates upon the form of the object studied, and the physiological which concentrates on function. Neither of these can attain full success without the other. The best results follow from some middle position“ (Goebel 1924: 35-35).

In relation to orchids, and in the same work, he stated: “[…] all the wonderful adaptations of orchid flowers are no more effective than countless much simpler devices. We find the intricate facilities of many orchid flowers, e. g. Catasetum with its technique for the ejection of the pollinia, Coryanthes with its lip bath for the flower visitors, as a work of art wonderful. But from a flat usefulness point of view, all this is “luxury adaptation”, which is understandable to us if, for the forms they exhibit, it was one that was determined and given throughout their entire organization. Then it is not a [superfluos] luxury but a purposeful one for an o r c h i d (i.e. taking into account only what has been a c h i e v e d). Selection theory rejects such a design, which takes place through internal causes in a definite direction, but it is neither sufficient to explain the “origin of the species” nor to convey to us an understanding of the diversity of adaptations: just because it removes the “logos” from morphology and wants to dissolve them into a mixture of directionless variations“ (letter spacing by von Goebel) (Goebel 1924: 35).

Francis E. Lloyd, who was well acquainted with Goebel’s work, described the latter’s point of view as follows: “Though he was little given to speculation, his wide and intimate knowledge of plant form led him to a modification of the Darwinian selection theory. He was convinced that the variety of plant form was much greater than the variety of the conditions under which they grow and saw in these various products many structures which could not be regarded as directly adaptive, but rather indifferent, being neither harmful nor useful. They can arise or disappear without being subject to selection, or they can group themselves and combine to produce members which may enable the plant to become adapted to quite other conditions than the primary ones, and the principle here implied was one of his chief guides in reflecting on the form relations of the plant” (Lloyd 1935: 206).

The Regnellian Herbarium

A Swedish physician and botanist, Anders Fredrik Regnell (1807-1884) (Fig. 20) studied in Uppsala and received his medical doctorate in 1837. He served for several years at the Serafimer Hospital in Stockholm and took part in an expedition to the Mediterranean Sea during 1839-1840 on board of HMS Jarramas.

Regnell was of poor health and suffered from a serious lung disease. Thus, looking for a warmer climate, he left Sweden for Brazil in 1840 and settled in Caldas in the province of Minas Gerais, where he spent the rest of his life. During his years in Brazil Regnell acquired a substantial fortune earned through his successful practice as a physician.

Regnell made substantial collections of plants, which he supplemented with those of G.A. Lindberg, S.E. Henschen, H. Mosén and J.F. Widgren. His collection was later bought by the Swedish government, to be divided between the Natural History Museum in Stockholm (NRM) and other institutions. The Regnellian Herbarium at NRM is today one of the largest collections of South American plants. In the last years of his life, Regnell endowed the Stockholm herbarium, established the Regnell Trust for the Medical Faculty in Uppsala, donated large sums to various Swedish scientific institutions and supported financially several European botanists. A travel grant he established in 1872 stated under its conditions that the chosen scholar was to collect plants in “Brazil, or another inter-tropical country” during a period of two years. The first of the so-called “Regnellian Expeditions”, financed through Regnell’s legacy, was in 1892- 1894 to Brazil, Paraguay and Argentina, led by C. A. M. Lindman and G. A. Malme. Over 20 other expeditions have taken place since then.

The orchid genus Regnellia, typified by Regnellia purpurea (=Bletia catenulata Ruiz & Pav.) (Fig. 21) was named in his honor by João Barbosa Rodrigues.

Carl Axel Magnus Lindman (1856-1928; collected 1892-1894)

Born in Halmstadt (southern Sweden), Carl Axel Magnus Lindman (Fig. 22) studied Botany and Zoology from 1874 at the University of Uppsala, where he was appointed Professor of Botany, receiving his Ph.D. in 1886. His early inclination for an artistic career became evident when he began producing magnificent botanical illustrations. He came as amanuensis to the Swedish Natural History Museum in Stockholm in 1887, and in 1892 received the first Regnellian grant. This financed a botanical expedition to South America in the company of Oskar Andersson Gustav Malme.

In July of 1892 the two botanists arrived in Rio de Janeiro and until September they explored the surroundings of the city and undertook excursions as far as Minas Gerais and San João d’el Rey. In September they embarked for Rio Grande do Sul and botanized near Porto Alegre, the German colony of Santo Angelo, the Italian colony of Silveira Martins and the colony of Ijuhy. After nine months in southern Brazil, Lindman and Malme embarked for Montevideo and Buenos Aires. From there they went by paddle steamer along the Parana River to Asuncion, the capital of Paraguay, and thence to the Gran Chaco region along the Pilcomayo and Apa rivers, until in November 1893 they again reached the province of Matto Grosso in Brazil. After nine months in the Matto Grosso, Lindman and Malme sailed to Argentina in August of 1894 and from there, via Santos and Bahia, to Europe, where they arrived at the end of October 1894.

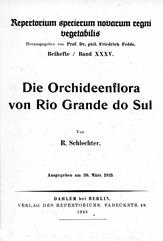

In 1925, Schlechter published his magnificent Die Orchideenflora von Rio Grande do Sul (Fig. 23). He described in this work some 30 orchid species collected by Lindmann, and an additional 9 collected by Malme. In the foreword, Schlechter wrote: The collections by Prof. Lindman and Dr, Malme will undoubtedly remain as fundamental for our knowledge of the flora of Rio Grande do Sul.

Schlechter named after him Lepanthes lindmaniana Schltr., while Kraenzlin named for Lindman the following orchids: Bifrenaria lindmanniana Kraenzl., Dipteranthus lindmanii Kraenzl. (Fig. 24A), Habenaria lindmaniana Kraenzl., Pelexia lindmanii Kraenzl., Rodriguezia lindmanii Kraenzl., Spiranthes lindmaniana Kraenzl. Stenorrhynchos lindmanianum Kraenzl. (Fig. 24B), and Vanilla lindmaniana Kraenzl.

Figure 24 A. Dipteranthus lindmanii (=Zygostates alleniana Kraenzl.). B. Stenorrhynchos lindmanianum [=Pelexia laxa (Poepp. & Endl.) Lindl. )]

In 1896 Carl M. Lindman became the tutor of the Swedish Crown Princes (among them the later King Gustav V), a position he held until 1900. He was elected to the Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1905 (Anonymous 1949). When a position for a Professor of Botany opened at the Swedish Natural History Museum, both Malme and Lindman applied. The position was given to Lindman, who held it until his retirement in 1923.

In 1900 Lindman published an interesting work entitled Vegetationen i Rio Grande do Sul (Sydbrasilien) [The vegetation of Rio Grande do Sul (Southern Brazil)]. However, the work for which he is best remembered is Bilder ur nordens flora (Illustrations of the flora of the North) One of its illustrations was the terrestrial Ophrys muscifera Hook. (Fig. 25).

The genus Lindmania Mez (Bromeliaceae) was named in Carl M. Lindman’s honor.

Gustav Oskar Andersson Malme (1864-1937; collected 1892-1894, 1901-1903)

Lindman’s travel companion, Gustav Oskar Andersson Malme (Fig. 26) was born in Soedermanland. He began bis studies in Stockholm before moving to Uppsala, where he received his Ph.D. in Botany and Zoology in 1892.

Gustav Malme’s itinerary during the 1892-1894 expedition has already been described since Lindman and Malme travelled always together. However, Malme’s harvest of Orchidaceae was much smaller than Lindman’s, at least according to Schlechter in his Orchideenflora von Rio Grande do Sul. This becomes evident if we examine the holdings of the herbarium of the Swedish Natural History Museum in Stockholm: a total of 333 orchid specimens collected by Lindman against 45 collected by Malme.

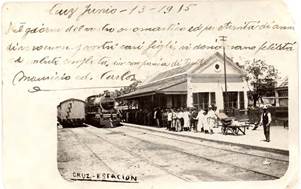

In 1901 Malme went on a new expedition to South America, on a second Regnellian grant. He arrived in Buenos Aires in October 1901 and travelled immediately to Porto Alegre, the capital of Rio Grande do Sul. There he had to stay for almost six months, and had to postpone his planned expedition to Aconcagua, on the border between Argentina and Chile, because war was threatening following several years of territorial disputes between the two countries. Matto Grosso was also out of the question, because of the civil war that was raging in the region. The unexpected stay was used to make botanical excursions to Cachoeira and Cruz Alta (Fig. 27). The latter became one of his favorite collection areas.

Finally, in March 1902, Malme decided to travel to Matto Grosso, intending to sail to Buenos Aires and from there take the steamboat along the Parana and Paraguay rivers to the village of Cuíaba. But because of an outbreak of plague he was held in quarantine for five days on the island of Flores, in Uruguay and arrived in Buenos Aires after the boat had already sailed. Malme then decided to take a freight boat to Corumbá (near the borders of Brazil, Bolivia and Paraguay), where he arrived in June. He went further on to Cuíaba and Santa Anna da Chapada (July through August). In his travel log Malme described Santa Anna as an “inexhaustible field for a botanist”. His plant collections grew so rapidly that he had to return to Cuíaba to sort and pack his specimens.

Finally, in January of 1903 Gustav Malme was able to begin his long-planned journey to Aconcagua, where he made further botanical collections at 3,000 meters above sea level. After another short visit to Matto Grosso, Gustav Malme finally embarked in Buenos Aires for his return to Europe in September 1903. Over the previous two years he had made a collection of over 2,600 plant specimens.

Kraenzlin described Physurus malmei Kraenzl. (Fig. 28) in Malme’s honor, while João Dutra named Pleurothallis malmeana after him.

A total of six plant genera have been named in honor of Gustav Malme, among them: Malmella and Malmia (lichens), Malmeomyces (fungi), Malmea (Annonaceae), and Malmeanthus (Asteraceae).

Eduard Martin Reineck (1869-1931; collected 1896-1899)

A German gardener from the city of Arnstadt, Eduard Martin Reineck (1869-1931) went to Brazil in 1896 accompanied by his assistant, Joseph Czermak, a merchant from Kassel. Together they botanized in the surroundings of Porto Alegre (Fig. 29), in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, until 1899. Their collections amounted to over 8,000 specimens, among them over 800 Phanerogamae which went for determination to John Isaac Bricquet, director of the Conservatoire Botanique at Geneva.

In a number of articles published in German botanical journals, Reineck described his excursions around Porto Alegre and to the Mountains around Belem Vélho. Orchids are frequently mentioned in his narrations. In his Riograndenser Orchideen, Cacteen und Baumbewohner (Orchids, Cacti and inhabitants of trees from Rio Grande do Sul), published in 1903, Reineck mentions a number of orchids, which he calls “flowers of fairy tales”, among them Oncidium barbatum Lindl., Oncidium sp., Spiranthes bracteosa Lindl., Epidendrum variegatum Jacq., Isochilus linearis (Jacq.) R. Br., Habenaria sartor Lindl., Cattleya guttata Lindl., Octomeria pusilla Lindl. Octomeria sp., Brassavola cordata Lindl., Cattleya intermedia Graham, Epidendrum elongatum Jacq., Habenaria parviflora Lindl., and Miltonia flavescens Lindl. Reineck mentioned that when he wrote this article (February 1899), his orchid collection comprised 25 different species (Reineck 1899, 2003).

Most of these species are listed by Schlechter in his Die Orchideenflora von Rio Grande do Sul (1925) . In this work Schlechter alss mentions, amongst Reineck and Czermak’s collections, specimens of Stenorhynchus paraguayensis (Rchb.f.) Cogn., Pleurothallis ruscifolia R. Br., Epidendrum mosenii Rchb.f., and Brassavola perrinii Lindl.

However, many of Reineck’s specimens of Orchidaceae could not be studied in detail since he split his collections and sold them to different herbaria. According to Schlechter, a complete collection of Reineck and Czermak’s specimens cannot be found.

The herbarium of the Natural History Museum in Paris holds several specimens of Orchidaceae collected by Reineck in Brazil: Cyclopogon apricus (Lindl.) Schltr., Oncidium flexuosum Sims (Fig. 30), and Miltonia flavescens Lindl. Another specimen, this of Brachystele bracteosa (Lindl.) Schltr., is kept at the Botanical Garden in Meise (Belgium).

Reineck paid a short visit to the area around Bahia Blanca, Argentina, in October 1899. However, he does not mention any orchids in his account of this excursion.

Eduard Reineck returned to Germany with his plant collections in 1899. These constituted the core of his commercial activities, which he began in 1901 and continued over the next 25 years. The years spent in Brazil gave Reineck a leading position among his contemporaries and in 1902 he was named editor of the Deutsche Botanische Monatsschrift, a position he kept until 1912. Reineck used this journal, as well as the Allgemeine Botanische Monatsschrift to advertise his collections of herbarium specimens (Fig. 31). The sale of these specimens would be Reineck’s main source of income for the rest of his life.

Also It is also worth mentioning that - as a supplement to his commercial activities - Reineck took active part in the Internationaler Botanischer Tauschverein (International Botanical Exchange Association), established in 1907, of which he was one of the founding members. Reineck’s activity becomes evident if we consider the number of public and private institutions with which he traded. We can find his plants in differrent European herbaria (BC, BM, BP, DBN, E, G, GH, GOET, HBG, K, L, M, MANCH, O, P, SAM, W), in America (AMES, MVM, SI, US), Asia (CAL) and even in South Africa (NH, SAM) (Benedí & Sáez, 1996:571). In total, over 8,000 specimens, proceeding from all continents, were offered and sold by Reineck.

Figure 31 Reineck’s advertisement for his Herbarium specimens, among them “South-European and foreign Orchids”.

Unfortunately, Reineck will not be remembered for his contributions to botany in general and orchidology (which in Schlechter´s words were unsatisfactory) in particular, but for his dubious business practices. It has been determined without doubt that Reineck, at least in the last 20 years of his commercial activity, falsified specimens, exchanged labels and disguised localities, all to add value to plants he was selling commercially.

We will not extend ourselves on this subject; enough has been written about Reineck’s false plants, as Benedí called them. Standley (1927), Benedí (1987) and Benedí & Sáez (1996) went into detailed research work and demonstrated that Reineck, when it came to selling herbarium specimens, was capable of anything. Paul C. Standley, in his article of 1927, shows how far Reineck could go in order to sell his false plants. Regarding Reineck’s falsification of Brother G. Arsène’s Mexican collections, Standley wrote: “The distributor of these plants was not content with ascribing specimens wrongly to Brother Arsène, but his ingenuity was equal to the creation of a new and fictitious collector, Herrera. This is a common Spanish family name, but I have no hesitation in asserting that this particular Herrera never existed. The name selected is not above criticism; Munchausen would have been a better choice. “Herrera’s” collections were manufactured from those of Pringle. In many instances the type collections of Pringle’s new species were thus divided. Here, too, only the name of the species was invariably retained. The date of collection is sometimes earlier and sometimes later than Pringle’s. The locality is usually the same, but often the altitude (given in feet on Pringle’s labels and in meters on those of “Herrera”) has been altered” (Standley 1927: 132).

Per Karl Haljmar Dusén (1855-1926; collected 1901-1916)

“Southern Brazil especially ranks amongst the better explored floristic regions, and Swedish botanists have contributed more than all others to the richness of our collections and our knowledge”. With these words Friedrich Kraenzlin introduced his Orchidaceae Dusenianae novae (1921) , in which he described the orchid collections of Per Karl Haljmar Dusén (Fig. 32) in the Brazilian states of Paraná and Santa Catharina. A few years earlier, Kraenzlin had already described new orchid species based on collections by Dusén in his Beiträge zur Orchideenflora Südamerikas (1911). Rudolf Schlechter would follow with the publication of new species by Dusén in his Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Orchidaceenflora von Paraná (only terrestrial orchids), and in 1925 with Die Orchideenflora von Rio Grande do Sul.

Per Karl Haljmar Dusén (1855-1926) was born in Vimmerby (province of Småland) in Sweden, where his father was director of a primary school. After studying at the Superior Technical High School of Stockholm, he graduated as a mechanical engineer. However, he only worked in this profession until 1880, when he accepted a position as professor at the Popular School for Natural Sciences and Mathematics, a post he held until 1898, when he was employed as an assistant at the Swedish Museum of Natural History. In his interest for Botany he was strongly influenced by his cousin, K. F. Dusén, of Kalmar, who was a renowned bryologist. Mosses were Dusén’s main interest during these initial years and he would dedícate considerable efforts to their study during the rest of his life. His first publication was about the flora and geology of the región of Omberg, in Oestergoetland.

Dusén travelled extensively and went on botanical expeditions to a large number of foreign countries: Tropical Africa (Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Liberia); North America (Greenland and Mexico): West Indies (Haiti); and South America (Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Brazil). But Brazil would be his favorite collecting ground. The expeditions there began in 1903-1904 -during which Dusén dedicated himself extensively to the study of the flora of the state of Paraná- and continued from 1908 to 1912 and from 1913 to 1916 (Hoehne 1930).

Dusén’s first encounter with the South American flora took place in 1895, when he participated in the expedition commanded by Otto Nordenskjoeld to study the natural history of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. Dusen collected three species of the terrestrial genus Chloraea during the expediton. We will come back to this part of Dusen’s life in future chapters concerning Chile and Argentina. Dusén returned to Sweden, but very soon, in September 1901, he was back in America, this time in Brazil. From 1901 to 1904 he held the position of assistant to the Botanical Section of the Natural History Museum in Rio de Janeiro, with a brief interlude in the city of Curitiba (state of Parana), his first Brazilian expedition, from November 1903 to May 1904.

Per Dusén’s life was adventurous. In 1905, in recognition of his knowledge of southern South America, he went again to Patagonia with a new expedition, this time led by Arthur Thessler, which started from Buenos Aires to study the possibilities of establishing a Finnish colony in Patagonia. During a severe snow storm, he almost lost his life. He extended his stay and in 1906 was contracted by the Chilean government as part of another expedition, this time for the exploration of the Aysén River and the topographical delimitation of the border between Chile and Argentina.

In 1908 Dusén was surprised by an invitation from the State Government of Paraná, to undertake the botanical exploration of the state. Dusén spent four years in Paraná, during which time he collected over 40,000 specimens of phanerogams and 800 specimens of mosses. After his return to Sweden, he received the third invitation from Paraná and spent the next three years (1913-1916) in the country.

It was not by chance that Dusén collected the vast majority of his plants in Paraná. Besides the exuberant flora of Paraná and the great number of undescribed plants in the region, an important factor was his friendship with C. J. F. Westerman, the railways director of Paraná state. Westerman provided him with a specially modified railway wagon, furnished as a dormitory and working place, with room enough for a laboratory for collections and research. Dusén thus travelled the region in his own railway carriage. After collecting in a particular area, his living quarters were coupled to a locomotive and taken to a new unexplored place. The researcher remained there during a further period, moving along once again when he finished his exploration. This is why most of the new species discovered by Dusén were collected along the route of the railways, ranging from São Paulo to Paraná and the borders of the state of Santa Catarina (Fig. 33).

The outbreak of WWI left Dusén in difficult financial circumstances and he was forced to return to Sweden again. In precarious conditions, he subsisted for a time on the income from the sale of his herbarium specimens. However, friends and relatives obtained a pension for him from the Swedish government in the amount of 3,000 crowns. On this modest sum he lived the remaining years of his life, dedicating himself to the study of his botanical material.

His legacy as a plant collector amounts to more than 70,000 vascular plants and 1,000 mosses (Fig. 34). Most of his collections are kept at the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm, but a large number can also be found in Brazilian herbaria in Rio de Janeiro and Curitiba. The Swedish Natural History Museum keeps a total of 1,593 orchid specimens collected by Per Karl Dusén, among them 64 types of plants new to science (Raulino Reitz 1949) (Fig. 35).

Figure 33 One of Duséns many collection areas: the railway station of Morretes, province of Paraná, ca. 1884.

Rudolf Schlechter described a large number of new orchid species from Dusen’s excursions in Parana in his Beiträge zur Orchidaceenflora von Paraná (1920). He wrote in the foreword: “Dr. Dusén gave me in the year 1918 the terrestrial orchids collected by him in the years of 1913-1916, for their determination. He also requested to review the determinations made by Prof. Kraenzlin from his earlier excursions. The collection has showed that we have to expect a large number of new species, even from regions in Brazil that were considered as well explored. The epiphytic orchids will be determined by Dr. Dusén himself” (Schlechter 1920).

Kraenzlin, on his side, published a number of new orchid species collected by Dusén in his Orchidaceae Dusenianae novae (1921).

Among the new orchid species collected by Dusén, 17 were dedicated to him by his contemporaries: 6 by Rudolf Schlechter (Cryptophoranthus dusenii, Cyclopogon dusenii, Cyrtopodium dusenii, Habenaria dusenii, Octomeria dusenii, Promenaea dusenii), one by Frederico C. Hoehne [Pleurothallis per-dusenii (Fig. 36)], 10 by Friedrich Kränzlin [Amblostoma dusenii, Bulbophyllum dusenii, Eulophia dusenii, Gomesa duseniana, Ornithocephalus dusenianus (Fig. 37), Polystachya dusenii, Psilochilus dusenianus Kraenzl. ex Garay & Dunst., Quekettia duseniana, Stenorrhynchos dusenianum, and Xylobium dusenii], and one by Alberto José de Sampaio [Restrepia dusenii (Fig. 38)].

Dusén was honored in the name of over 160 plants through epithets such as “dusenii”, “duseniella”, “dusenianus”, etc. In addition, a new genus, Dusenia O.Hoffm. in the Asteraceae, was dedicated to him. was dedicated to him. On his part, Dusen dedicated a new orchid species to Rudolf Schlechter: Pleurothallis schlechteriana Dusén (ined.) (Fig. 35).

The herbarium Per Karl Dusén in Curitiba (PKDC) was named in his honor.

Frederico Carlos Hoehne (1882-1959; collected 1908-1959)

As one of the eight children of German immigrants, who had arrived (themselves children) in Brazil in 1858, Frederico Carlos Hoehne (Fig. 39) was born in Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais. Hoehne’s father, a farmer, had a small orchid collection that became an attraction for visitors, and many of the plants were sold to contribute to the family’s economy. At just eight years of age, Hoehne started his own orquidário and he later wrote that his interest in botany had begun at that time.

Having finished his high school studies in 1899, and without the means to finance an academic career, Hoehne had to educate himself while he continued with the observation of plants, living in part from the sale of orchids.

Specialized books were brought from Rio de Janeiro and the orchid collection, which he learned to determine and classify, was expanded, now also from exchange with other growers. His ambition was now to discover new species. Young Hoehne’s orchid collection soon replaced that of his father and became locally famous. By 1907, at the age of 25, Hoehne had turned into an expert, consulted by orchidophiles and orchidologists. It was in that year that his career took a dramatic turn: with the help of the President of the Municipal Council of Juiz de Fora, Hoehne - without a formal scientific education - was appointed chief-gardener of the National Museum of Rio de Janeiro, at that time the largest scientific institution in the country. The museum, founded in 1818, was moved, in May of 1900, from its original location to the former Palácio Imperial de São Cristóvão, also known as Quinta da Boa Vista (Fig. 40).

One year later, in 1908, Frederico C. Hoehne was called to form part of the first of the famous expeditions led by Colonel Cândido Mariano da Silva Rondon (1865-1958) (Fig. 41). Rondon was well known for his lifelong support of the indigenous Brazilian tribes. He became later the first director of the Indian Protection Service and supported the creation of the Xingu National Park. The Brazilian state of Rondônia is named after him.

Rondon led three major expeditions into the Matto Grosso, surveying the lands between Matto Grosso and the Amazon (1908-1909), laying telegraph lines between Brazil and Bolivia in 1910 and finally, in 1913-1914, leading the Roosevelt-Rondon Scientific expedition to the Rio da Dúvida (“River of Doubt”), afterwards named Rio Roosevelt or sometimes Rio Teodoro.

The expedition, led by former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt and Cândido Rondon (Fig. 42), sought to determine where and by which course the river flowed into the Amazon. Roosevelt, together with his son Kermit, undertook this adventure after failing to retain his office in the elections of 1912. A fervent lover of nature, Roosevelt had used his authority to protect wildlife and public lands by creating the United States Forest Service and establishing 150 national forests, 51 federal bird reserves, 4 national game preserves, 5 national parks, and 18 national monuments.

Hoehne was chosen as the botanist of these expeditions (during the second he had the company of his brothers-in-law Hermano and Geraldo Kuhlman) and later made significant contributions to the expeditions’ reports (published between 1910 and 1923), detailing their botanical findings. In some of these reports (Hoehne 1914, 1916, 1916a) he described and illustrated a large number of orchid species. Among them, he dedicated to Rondon and Roosevelt Sobralia rondonii and Catasetum rooseveltianum respectively (Fig. 43).

In the course of Rondon’s expeditions, Hoehne and his collaborators collected over 10,000 plant specimens, corresponding to at least 4,000 different species, of which 200 had not previously been described. Thus, Hoehne finally realized the dream of his youth of discovering plants new to science. In addition, dozens of plants of the native Brazilian flora where named in his honor, as homage from his colleagues, assistants and admirers. Frederico C. Hoehne was honored by numerous institutions, among them the American Orchid Society made him an honorary member and the University of Göttingen, Germany conferred the title of Doctor Honoris Causa, on him in 1929.

It was in the city of São Paulo (where he moved in 1917) that Hoehne reached the high point of his scientific career and followed a systematic pursuit both in the study and the protection of nature. His career was intimately related to the foundation of the Instituto de Botânica do Estado de São Paulo, where in 1917 he was given the task of organizing a botanical garden for the cultivation and acclimation of medicinal plants. At the same time, he dedicated himself to a larger project, the establishment of a Botanical Section at the Instituto Butantã, on the outskirts of São Paulo.

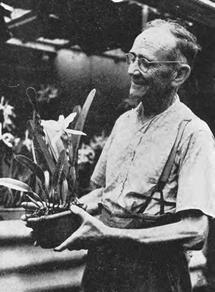

Figure 44 Fernando Costa (left) and Frederico Hoehne with the first orchids that arrived at the Botanical Garden of São Paulo in 1928.

Hoehne’s research related to the Brazilian orchid flora had the support of Rudolf Schlechter, botanist from the Botanical Museum of Berlin-Dahlem. The scientific exchange of knowledge and natural history material proved to be, throughout the 19th century, the most efficient form of gathering collections of universal character. This idea has persisted until the present. Hoehne and Schlechter corresponded from 1919; the latter became an avid collaborator of those studying the orchid flora of Brazil and was, among German botanists, the first to recognize the scientific merits of Barbosa Rodrigues.

In 1928 Hoehne was called by Fernando Costa, Secretary of Agriculture of the state of São Paulo to make plans form the organization of a botanical garden, that would grow and exhibit the most interesting ornamental plants of the indigenous flora (Hoehne 1941:14). The Botanical Garden of São Paulo was established in an area that had been preserved since 1893 because of the natural springs that existed in the area which provided water to the eastern suburbs of São Paulo. The springs were abandoned in 1928 due to falling water levels and the land was assigned to the new botanical garden. Roadsand two hothouses were built. The Orquidário was formally inaugurated in 1930 although the first orchids had already arrived at the garden in 1928 (Fig. 44).

The garden gained more autonomy when it was subordinated to the Secretary of Agriculture, Industry and Commerce and in 1942 became the Department of Botany, a status it holds until the present day. Hoehne worked in the garden until 1952, when he had to go into compulsory retirement because of his age.

Figure 45 A. Itaculumia ulaei. B. Yolanda restrepioides (left). C. Rudolfiella auantiaca. D. Prescottia schlechteri (as P. colorans Lindl.).

Frederico C. Hoehne published his Contribuções ao Conhecimento das Orchidáceas do Brasil in 1922. Part I was published in collaboration with Rudolf Schlechter; parts II and III in co-authorship with the German botanist Kurt Krause, a former collaborator of Schlechter’s. But Hoehne’s major work was the Flora Brasilica, begun in 1940 and carried on after his death by Acides Ribeiro Texeira. Twelve fascicles were issued up to 1968. His last major publication was Iconografia de Orchidaceas do Brasil (1949) (Silva 2013).

The São Paulo journal Hoehnea (1971-) is named after him, as are the genera Hoehnea Epling (Lamiaceae), Hoehnella A.Ruschi (Orchidaceae) and Hoehnephytum A.L.Cabrera (Asteraceae).

Between 1908 and 1948 Frederico C. Hoehne described over 1,000 new species of plants of which some 450 were orchids. Among his discoveries, he published four new orchid genera: Itaculumia (Fig. 45A), Loefgrenianthus, Yolanda (Fig. 45B) and Rudolfiella (Fig. 45C). A total of seven orchids named by Hoehne after Rudolf Schlechter are proof of the life-long friendship and collaboration between the two botanists: Epidendrum rudolfianum, Habenaria rudolfi- schlechteri, Maxillaria rudolfii, Habenaria rudolfi- schlechteri, Physurus schlechterianus, Prescottia schlechteri (Fig. 45D), and Theodorea schlechteri.

A large number of species of Orchidaceae were named after Hoehne by different authors. Rudolf Schlechter dedicated to Hoehne Acacallis hoehnei, Cryptophoranthus hoehnei, Habenaria hoehnei, Maxillaria hoehnei (Fig. 46), Octomeria hoehnei, Pleurothallis hoehnei, and additionally Cleistes hoehneana Schltr. ex Mansf. and Oncidium hoehneanum Schltr. ex Mansf. In a similar way, Kraenzlin described Polystachya hoehneana. Guido Pabst followed with Brachystele hoehnei and Camaridium hoehnei. And finally, a number of authors dedicated orchids to him, so Bulbophyllum hoehnei E.C.Smidt & Borba, Catasetum hoehnei Mansf., Cattleya hoehnei Van den Berg (Fig. 47), Epidendrum hoehnei A.D.Hawkes, Eurystyles hoehnei Szlach., Lankesterella hoehnei Leite, Maxillaria hoehneana P.F.Hunt, and Mormodes hoehnei F.E.L.Miranda & K.G.Lacerda.

João Gerlado Kuhlmann (1882-1958; collected 1910-1943)

In December of 1910 Frederico C. Hoehne returned to the Matto Grosso on his second expedition led by Cándido Rondon again in charge of the botanical work. Unable to find skilled assistants in the region, Hoehne was permitted to bring this brothers- in-law Hermano and João Geraldo Kuhlmann (Fig. 48) from Rio (Hoehne had married Clara Eduarda Frieda Kuhlmann in 1907).

Over the next 19 months, Hoehne and the Kuhlmann brothers explored the forests and fields, collecting botanical specimens along the Juruena and the Tapajós rivers. They finally reached Santarém and continued from there to Belém, repeating - 83 years later - the route of Baron von Langsdorff’s expedition in 1828 (after Sá et al. 2008).

Born from German parents in the German colony of Blumenau, in the southern state of Sta. Catharina, Kuhlmann was a largely self-taught botanist (as was his brother-in-law F.C. Hoehne). His formal education never went further than Blumenau´s primary school (Fig. 49)], but over the years he would become one of Brazil’s leading botanists.

Invited by director Antonio Pacheco Leão, Kuhlmann joined the Botanical Garden of Rio in 1919, where he was put in charge of the Botanical Section and at the same time taught at the Superior School of Agriculture and Veterinary Science of Viçosa. Finally, in 1944 he was named by the Secretary of Agriculture Director of the Botanical Garden in Rio de Janeiro, a post he held until 1951. Under his administration, scientific research flourished at the garden, especially since Kuhlmann could count on brilliant collaborators, such as Adolpho Ducke and Alexander Curt Brade.

Kuhlmann and his family lived on the garden premises, in a house called Casa dos Pilões (Fig. 50), the Pestle House, built as a production unit of the Royal Gunpowder Factory at Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon, where the Botanical Garden of Rio had been founded by King João VI in 1808. In 1960, after Kuhlmann’s death, the Federal Government established the “Museu Botânico Kuhlmann” in this house (Reitz 1972).

João Geraldo Kuhlmann was Honorary President of the International Botanical Congresses at Tucumán, Argentina (1940), Stockholm (1955) and Paris (1954). The Herbário Rondoniense João Geraldo Kuhlmann was established in 2009 at the Federal University of the state of Rondônia.

During his early expeditions with Hoehne and later, until his nomination as Director of the Botanical Garden in Rio, Kuhlmann was an avid collector. Among his specimens we find a small group af orchids at the Oakes Ames Orchid Herbarium of Harvard University: Epistephium parviflorum Lindl., Epistephium subrepens Hoehne, Habenaria amazonica Schltr., Habenaria depressiflora Hoehne, Habenaria duckeana Schltr., Habenaria leaoana Schltr., Habenaria marupaana Schltr., Habenaria platydactyla Kraenzl., and Habenaria trifida Kunth. Many of them were described by Schlechter in his Orchidaceae kuhlmannianae (1926).

The following orchid species were named in Kuhlmann’s honor: Campylocentrum kuhlmannii Brade, Centrogenium kuhlmannianum Hoehne (Fig. 51A), Epidendrum kuhlmannii Hoehne, Neobartlettia kuhlmannii Schltr.(Fig. 51B), Habenaria kuhlmannii Schltr. (Fig. 51C), Epidendrum geraldoi Porto & Brade, and Zygostates kuhlmannii Brade.

Alexander Curt Brade (1881-1971; collected 1910-1971)

In 1923 Rudolf Schlechter described a new orchid species collected in Costa Rica, which he named Liparis fratrum (Fig. 51D). Few know that fratrum is a Latin genitive that translates literally as “belonging to the brothers”. Schlechter had chosen this name in honor of two German brothers who had made important orchid collections in Costa Rica: Alfred Brade and his younger brother Alexander Curt Brade (Fig. 52).

Alfred Brade (1867-1955) had arrived at Puerto Limón in 1893 and after two years of work in the banana plantations of the Atlantic region found a position in the nurseries of Julian Carmiol in San José. With Carmiol he shared his enthusiasm for Botany and he dedicated himself for years to explore all accessible regions in the country. After several years he made himself independent from Carmiol and founded the Brade Nurseries. With the years he dedicated himself more and more to horticulture and finally abandoned botanical exploration completely (Ossenbach 2009: 151). Alexander Curt Brade, by profession a civil engineer, was the driving force behind those collections. Alexander Curt came to Costa Rica in 1908 invited by his brother but stayed only for a short time, traveling in August of 1910 to Brazil, where he reached glory as one of South America’s greatest orchidologists. Rudolf Schlechter, in his Additamenta ad Orchideologiam Costaricensem (1923) dedicated an entire chapter to the collections that he had received from the Brade brothers: Orchidaceae Bradeanae Costaricensis. He was very specific to use this title because he later published Orchidaceae Bradeanae Paulensis to distinguish the Brazilian from the Costa Rican Brade collections (Ossenbach, 2009: 151).

Schlechter praised the great quality and excellent preparation of the Brade’s herbarium specimens and called the collection “a milestone in the botanical exploration of the country”(Markgraf 1973: 4).

Alexander’s intention to return to Germany was postponed after receiving an invitation from his nephew, the surveyor Walter Petry, to visit him in southern Brazil. He sailed via New York to Santos. A few days were spent in Rio de Janeiro, where Brade climbed Corcovado and Tijuca Peak, without guessing that years later he would develop his most important scientific activity here. The journey went on to Santos and then Iguapé along the Pariquera Mirim River (Fig. 53). Here again Brade found a neo-tropical flora, which was, however, quite different from the Central American flora he had studied in Costa Rica.

Alexander Brade worked in São Paulo as engineer in charge of a new building for the local brewery and at the same time as a surveyor with his nephew. He spent his free time exploring the dry vegetation of the ‘Campos’ and in the luxuriant forests of the Serra do Mar. His living seemed secured and in 1916 he found in Hanna Kähler a companion for his life. World War I had begun in Europe but Brazil seemed far away and Brade felt no danger. It was not until 1917, when Brazil declared war on Germany, that Brade -like all other German employees- lost his job at the brewery. He had to find a new way of earning a living and -again with his nephew- bought a neglected ‘Fazenda’, Morro de San Pedro, on the banks of the Peroupava River. Slowly he brought the farm into the production of rice and sugar cane. After 10 years he was again in a comfortable position only to lose, in 1928, all his possessions to a terrible flood. Brade and his family barely escaped with their lives.

It was destiny that showed Brade a way out of this desperate situation. During his years as fazendero he had not wasted time but kept collecting plants. His herbarium had already over 10,000 specimens and he sent most of them for determination to the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro. The Director of the Botany Department, Professor Sampaio, offered him a position as free-lance botanist (botanico contratado). Brade would live the rest of his life on Botany.

He gave up the idea of returning to Germany. Later, after 1945, a return to his homeland became totally impossible: the family possessions were destroyed, and most of his relatives had died during the war. In 1933 Brade adopted Brazilian citizenship and could thereafter take a full-time position as botanist at the Botanical Garden in Rio - at the time under the directorship of Paulo Campos Porto - until he was named Director of the Section of Systematic Botany (Chefe da Seccão de Botanica Sistemática). In this position he travelled extensively in the states of Rio de Janeiro, Espirito Santo and Minas Gerais until in 1952 he was forced to retire, having reached the mandatory retirement age of 70. His passion for botany continued however to his last days.

Alexander Curt Brade published a large number of articles on the flora of Brazil. Two among them - which he published in co-authorship with Campos Porto - are of special importance for us: INDEX ORCHIDACEARUM in Brasília inter MDCCCCVI et MDCCCCXXXII explorata sunt (1935) and Orchidaceæ Novæ Brasilienses I-VIII (1935-1958).

Brade’s botanical work was enormous. Orchidaceae was one of his favorite plant families, and he established close relationships with all the important orchidologists of his time: Paulo Campos Porto, Rudolf Schlechter, Frederico C. Hoehne, Guido Pabst, and Friedrich Kraenzlin. He described a number of new orchid genera and dozens of new orchid species.

Among the orchid genera described by Brade or by Brade & Campos Porto, we find: Pygmaeorchis Brade, Duckeella Porto & Brade (Fig. 54), Eunannos Porto & Brade, Pleurothallopsis Porto & Brade, and Pseudolaelia Porto & Brade.

TABLE 1 Orchid species described by Alexander Curt Brade.

| Bifrenaria caparaoensis Brade Bifrenaria villosula Brade Bulbophyllum adiamantinum Brade Bulbophyllum campos-portoi Brade Bulbophyllum vaughanii Brade Campylocentrum iglesiasii Brade Campylocentrum kuhlmannii Brade Capanemia duseniana Brade Centroglossa castellensis Brade Cirrhaea nasuta Brade Cryptarrhena brasiliensis Brade Cryptophoranthus jordanensis Brade Cycnoches espiritosantense Brade Cyrtopodium intermedium Brade Dichaea mattogrossensis Brade Dipteranthus ovatipetalus Brade Encyclia advena Brade Encyclia albopurpurea Brade Encyclia bicornuta Brade Encyclia conspicua Brade Encyclia euosma Brade Encyclia gallopavina Brade Encyclia jenischiana Brade Encyclia megalantha Brade Encyclia pauciflora Brade Encyclia purpurachyla Brade Encyclia randii Brade Encyclia xipheroides Brade Encyclia yauaperyensis Brade Epidendrum geraldii Brade Epidendrum geraldoi Brade Epithecia mattogrossensis Brade Lepanthopsis congestiflora Brade Lepanthopsis unilateralis Brade Maxillaria caparaoensis Brade Maxillaria matogrossensis Brade Maxillaria modesta Brade Mormodes amazonica Brade Mormodes amazonica Brade Notylia trullulifera Brade Platystele brasiliensis Brade Pleurothallis adamantinensis Brade Pleurothallis adirii Brade Pleurothallis bocainensis Porto & Brade Pleurothallis caparaoensis Brade Pleurothallis carrisii Brade Pleurothallis castellensis Brade Pleurothallis gracilisepala Brade Pleurothallis guimaraensii Brade Pleurothallis imbeana Brade Pleurothallis mathildae Brade Polystachya rupicola Brade Pygmaeorchis brasiliensis Brade Saundersia paniculata Brade Scaphyglottis matogrossensis Brade Stenocoryne caparaoensis Brade Stenocoryne villosula Brade Theodorea paniculata Brade Theodorea paniculata Brade Thysanoglossa organensis Brade Trichopilia santos-limae Brade Trichopilia santoslimae Brade Zygostates kuhlmannii Brade |

The list of new orchids described by Brade finds no end (Table 1). A great part of these species was described in Schlechter’s Orchidaceae Bradeanae Paulensis (1925a).

Campos Porto and Brade described an important number of new orchid species: Capanemia adelaidae, Centrogenium janeirense, Centrogenium schlechterianum, Centroglossa nunes-limae, Constan- tia cipoensis, Duckeella adolphii (Fig. 54), Encyclia squamata, Epidendrum duckei, Epidendrum janeiren- se, Epidendrummagdalenense, Epidendrummantique- ranum, Hapalorchis pauciflora, Octomeria anceps, Octomeria cucullata, Phymatidium limae, Pleuro- thallis bocainensis, Pleurothallis lichenophila, Pleurothallis limae, Pleurothallis radialis, Pseudo- laelia corcovadensis, Thysanoglossa jordanensis, and Zygostates octavioreisii.

Aditionally, a number of new orchids was described by Hoehne & Brade: Cladobium spannagelianum and Pleurothallis peroupavae; and by Brade & Pabst: Erythrodes fissirostris, Erythrodes mendoncae, Habenaria mello-barretoi, Octomeria itatiaiae, and Pelexia magdalenensist.

Before Brade’s botanical knowledge had grown to the point of allowing him to make his own determinations, his orchid specimens were determined by others. The largest number were described by Rudolf Schlechter: Cranichis bradei, Cyclopogon bradei, Cyrtopodium bradei Schltr. ex Hoehne, Dipteranthus bradei, Habenaria bradei, Maxillaria bradei, Pelexia bradei Schltr. & Mansf., Physosiphon bradei, Pleurothallis bradei, Polystachya bradei Schltr. ex Mansf., Pseudostelis bradei, Spiranthes bradei, Stenorrhynchos bradei, and Vanilla bradei Schltr. ex Mansf.

Hoehne described from Brade’s collections Habenaria curti-bradei Hoehne, Cyrtopodium bradei Schltr. ex Hoehne, and Masdevallia bradei Schltr. ex Hoehne. Finally, Kraenzlin described Epidendrum bradeanum, Habenaria bradeana and Pogonia bradeana, and Guido Pabst Laelia bradei (Fig. 55), and Pleurothallis curti-bradei.

The herbarium of the Botanical Garden in Rio de Janeiro and its scientific journal were named in Brade’s honor Herbarium Bradeanum and Bradea, respectively (Scheliga 2003) (Fig. 56).

Paulo Campos Porto (1889-1968; collected 1917-1936)

As the grandson of Brazil’s greatest orchidologists of the 19th century, João Barbosa Rodrigues, it can be said that Paulo Campos Porto (Fig. 57) was born with orchids in his blood.

Campos Porto occupied important positions in botanical institutions during his life, and together with Hoehne, Brade, Pabst, Kuhlmann and a few others formed the nucleus of Brazilian orchidology during the first seven decades of the 20th century. In 1914, with a position as naturalista viajante, he became part of the staff of the Botanical Garden of Rio de Janeiro, an institution he would serve as Director during the periods of 1933-1938 and 1951-1958. He was also Director of the Institute of Plant Biology and Director of the Audit Council for the Brazilian Scientific and Artistic Expeditions. He occupied the position of Secretary of State for Agriculture of Bahia, where he was involved in the creation of the Monte Pascoal National Park (1951).

An important milestone in Campos Porto’s life was his participation in the Federal Forest Council and in the Organizatory Committee for the creation of the Itatiaia National Park (Fig. 58). His activity in this Committee was fundamental to the constitution of the Itatiaia Forest Reserve. It had been already decided that the reserve would be managed as a dependency of the garden in Rio (1914). The first land had been bought in 1908, and the first steps leading to the constitution of the reserve were undertaken after Antônio Pacheco Leão took over as Director of the Botanical Garden in Rio, in 1915. The creation of the Itatiaia Biological Station (1929) led to the subsequent formal creation of the Itatiaia National Park, the first national park in Brazil (1937) (Fonseca Casazza 2014).

Aside from his involvement in the purchase of the land where the Biological Station was later established under his direction, Campos Porto began a systematic exploration of the region in 1915, organizing constant botanical excursions to the Serra de Itatiaia. In several of these excursions he was accompanied by Maria do Carmo Vaughan Bandeira (1902-1992), a young botanist who was the first woman to hold a position as researcher at the Botanical Garden in Rio (Fig. 59). Maria Bandeira, for reasons still unknown, abandoned her promising career in 1931 and went into a convent in Rio where she lived for the rest of her life as a cloistered nun (Bediaga et al. 2016).

Figure 59 Maria Bandeira and Campos Porto in front of the Biological Station of the Itatiaia Forest Reserve (now Itatiaia National Park).

The activities of Campos Porto in the study and protection of Brazil’s natural heritage was, however, not limited to Itatiaia. The 1930s were marked by the revolution of 1930, which brought to power Getúlio Dornelles Vargas, who in November of that year was named President of the Provisional Government. Among other aspects of the Vargas Government (who remained in power until 1945) was the idea of establishing measures for the protection of natural areas. In this process, botany played an important role. A series of protectionist laws were approved during this period, among them the National Codes for Forestry, Hunting and Fishing, Water and Mines, and the establishment of the Audit Council for the Brazilian Scientific and Artistic Expeditions, of which Paulo Campos Porto became Director. This council was created in 1932, with the purpose of establishing rules and codes for private national and foreign expeditions across the country.

In addition to these official duties, Campos Porto took part in other scientific and environmentalist activities. He was member of the Technical Council in the First Brazilian Conference for the Protection of Nature in 1934 and in 1938 organized the First South American Botanical Conference. All this, together with the positions of Director of the Institute of Plant Biology and the Botanical Garden of Rio de Janeiro, converted Campos Porto into a cornerstone of nature conservation policies during the first years of the Vargas government.

The conservation of Brazil’s natural heritage in the light of science, the appreciation of its beauty and the research into its economic possibilities is not a novel ideal but already a deep concern of a group of scientists in the first decades of the 20th century.

Campos Porto described only one orchid by himself: Cattleya itatiayae Porto. Many others were described by him in co-authorship with Alexander Curt Brade (see previous chapter). Together with Schlechter he described the genus Leaoa Schltr. & Porto with its type species Leaoa monophylla Schltr. & Porto (Fig. 4). Finally, based on collections by Loefgren he described Maxillaria barbosae Loefgr. ex Porto and Pleurothallis glandulifera Loefgr. ex Porto.

The following species of Orchidaceae were named in his honor: Bulbophyllum campos-portoi Brade (Fig. 60), Encyclia campos-portoi Pabst, Epidendrum campos-portoi Barberena, Habenaria campos-portoi Schltr., Octomeria campos-portoi Schltr., and Stelis campos-portoi Garay (Fig. 61).

Albino Hatschbach Sobrinho (1874-1973; collected 1915-1925)

In his Orchidaceae HatschbachianaeSchlechter (1926a) wrote: “I received since the years of 1920 in regular intervals from Mr. Albino Hatschbach in Curytiba, Parana, small packets of orchids for determination […] Our knowledge about the orchid flora of Parana and the distributuion of the species is, after receiving this collection, now much more complete. It is, after the collections of Dr. Peter Dusen, undoubtedly the most important ever gathered in Parana” (Schlechter 1926a: 32). With these words, Schlechter introduced one of the most important and successfull plant collectors who worked in Paraná, Brazil’s southernmost state, during the first decades of the 20th century, Albino Hatschbach Sobrinho (Fig. 62), the son of an Austrian father and a Brazilian mother.

The orchid colllection described by Schlechter in his above quoted work comprised a total of over 140 specimens, mostly epiphytes; for Schlechter a welcome supplement to the orchids of Per Dusen, who had sent to Berlin mostly terrestrial plants.

At the age of nine Hatschbach was sent to Germany to complete his studies. He spent a total of nine years there, during which time he became familiar with the work of Rudolf Schlechter; this awoke in him the passion for orchids. Albino Hatschbach returned to Curitiba in 1908 to work in his grandfather’s shoe factory.

His love for orchids received a new impulse from one of his neighbors, Bruno Rudolf Lange (see below), one of the first orchid collectors in Paraná. Together with Lange, Hatschbach made long excursions to the Atlantic forests and collected large numbers of orchids, which he sent occasionally to Schlechter in Berlin for determination. Schlechter published Hatschbach’s specimens in his Beitraege zur Kenntnis der Orchidaceenflora von Parana II, Orchidaceae Hatschbachianae (1926a). He described them as so extraordinarily well prepared that in most cases a determination could be easily made.

Hatschbach established also a working relationship with Per H. Dusén, who collected in Parana during his time.

Orchids became his main pastime and Albino Hatschbach became a pioneer or orchid culture in Curitiba. He was one of the founders of the Sociedade Paranaense de Orquidófilos and its president for several periods.

In 1925 he returned to Germany; he had been invited by Schlechter to visit him in Berlin. However, on his arrival in Lisbon he received from Dr. Mansfeld the sad news that Schechter had passed away just a few weeks before. Nevertheless, he continued his journey and soon arrived in Dahlem, the suburb of Berlin where the Botanical Museum had been established. He wanted to revere in loco the memory of the great botanist. After wandering through the workrooms and admiring the collection of over 5,000 drawings of orchid species, all made by Schlechter himself, he met Dr. Mansfeld, who at that time was already an authority on orchids. Several years later, in an interview with Edmundo Gardolinski, Hatschbach remembered Mansfeld’s words: “Schlechter’s knowledge of orchids was at a level that nobody would reach without working at least 10 years at it”. Hatschbach left Berlin, “this paradise of the world of orchidology”, as he said, “with deep sadness and much sorrow” (Gardolinski 1960: 141).

Hatschbach then began corresponding with Frederico Carlos Hoehne, who already had a excellent reputation in the orchid world. Years later he corresponded also with Guido Pabst, a rising star in Brazilian orchidology. Pabst asked him in one of his letters to collect for him specimens of Oncidium albinoi (Fig. 63A), which he had never seen. Hatschbach regretted to answer: “in the place where I found these plants there are today only houses” (Anonymous 1974: 258).

Figure 63 A. Oncidium albinoi [as Baptistonia albinoi (Schltr.) Chiron & V.P. Castro]. B. Pleurothallis hatschbachii [as Pleurobohryum hatschbachii (Schltr.) Hoehne]. C. Maxillaria hatschbachii (as M. madida Lindl.). D. Octomeria hatschbachii.

It was with good reason that Schlechter wrote, after the end of World War I: “Since in today’s Germany no one is in the condition to pay for these [Hatschbach´s] collections, we do but only one thing, to erect a symbolic monument by giving his name to the new species” (Gardolinski 1960: 140). Thus, Schlechter dedicated to Hatschbach the following new orchid species: Capanemia hatschbachii, Cyclopogon hatschbachii, Oncidium albinoi (Fig. 63B), Pleurothallis hatschbachii (Fig. 63A), Maxillaria hatschbachii (Fig. 63C), Epidendrum hatschbachi, Octomeria hatschbachii (Fig. 63D), and Oncidium hatschbachii.

Albino Hatschbach died in 1973. He left two sons, Erin Hatschbach and Gert Hatschbach (1923-2013) The latter, Gert, following in his father’s footsteps, studied botany; in 1966 he founded the Botanical Museum of the city of Curitiba.

The orchids collected by Gert Hatschbach were described mainly by Frederico Carlos Hoehne. The Orchid Herbarium of Oakes Ames, at Harvard University, holds the following specimens collected by G. Hatschbach: Brachystele hatschbachii Pabst, Epidendrum avicula Lindl., Pleurothallis bacillaris Pabst, Pleurothallis bleyensis Pabst, Pleurothallis gonzalezii Pabst, and Pleurothallis piraquarensis Hoehne.

Dedicated to Gert Hatschbach were: Pleurothallis gert-hatschbachii Hoehne (Fig. 64), Cleistes gert-hatschbachiana Hoehne, Brachystele hatschbachii Pabst, Cyrtopodium hatschbachii Pabst, Psilochilus hatschbachii Kolan., Habenaria hatschbachii Pabst, and Bulbophyllum hatschbachianum E.C.Smidt & Borba.

A word must be said about the fundamental role that the Parana Railway played in the botanical exploration of the state. Roads were limited to urban areas and their surroundings, and only the railway was able to transport botanists and plant collectors into promising plant collection areas. This was the case - as we have seen - for Per Dusén, but it was no different for Hatschbach, nor - as we will see - for Bruno Rudolf Lange.

The main part of this railway network was the line from the Atlantic port of Paranaguá to Curitiba, which was constructed between 1880 and 1884 (Fig. 65). The work was divided into three parts: Paranaguá−Morretes, Morretes−Roça Nova, and Roça Nova−Curitiba. If we look at the collecting localities mentioned by Schlechter in his works about the orchid flora of Parana, we will find that over half of them, are close to the train stations on this route.

Bruno Rudolf Lange (1860-1922; collectd 1890-1935)

Born in Leipzig, Germany, Bruno Rudolf Lange (Fig. 66) arrived in Curitiba, the capital of the state of Parana, in 1883 as a result of the Brazilian Government’s program of recruiting European engineers for the construction of the southern railroads.

As already mentioned, Lange was the first to induce Hatschbach into collecting orchids. Additionally, as engineer in charge of the railway, he was instrumental in securing both Dusén and Hatschbach safe, fast transportation to the most remote collecting areas along the Paranaguá-Curitiba line. Along this line, one of the stations was built at a point named Volta Grande and inaugurated around 1904. In 1925 this station was renamed in Lange’s honor as Estaçao Engenheiro Lange, and still exists (Fig. 67). Bruno R. Lange was also responsible for other important projects, such as the reform of the Curitiba Train Station, and those of Paranaguá and Antonina.

Lange’s descendants played important roles in the artistic and scientific life of Parana. His son Frederico Augusto Lange was a famous painter and a researcher in malacology; his grandson Rudolf Bruno Lange became one of the most famous naturalists of Parana, a specialist in entomology, matozoology and orniothology, and Director of the Paraná Museum in Curitiba while teaching at the Catholic University of the state.

Lange made a small collection of orchids, among which we find Pelexia hysterantha (Rodr.) Schltr. and Cyclopogon chloroleucus (Rodr.) Schltr., as well as two new species that were dedicated to him: Cyclopogon langei Schltr. (Fig. 68) and Pleurothallis langeana Kraenzl.

At the end of this chapter we want to mention a few collectors who made smaller, albeit important contributions to the knowledge of the orchid flora of Rio Grande do Sul. Little is known about their lives, the biographical information publicly available is too scarce. However, their orchid collections brought to light a number of new orchid species, all of them described by Schlechter in 1925 in his Orchideenflora von Rio Grande do Sul.

Francisco D’Aquino (?-?) and L. Burger (?-?); both collected 1910-1925

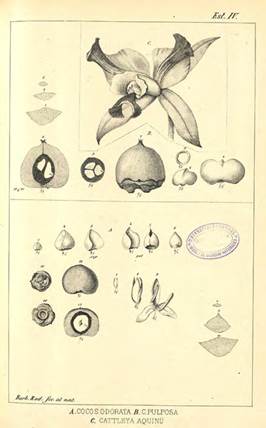

In 1942, Urbano Kley published an article in Orquidea, under the title Cattleya aquinii Barb. Rodr. In a free translation, here is what he had to say about the history of this plant: “as a friend and disciple of the late Francisco d’Aquino, and knowing the history of this plant, I have dared to write this brief historical sketch, wishing to contribute to the knowledge of the circumstances leading to the discovery of this botanical treasure. Around the years 1874 to 1875, Mr. Antonio J. da Silva Valadares, from the capital of Rio Grande do Sul, received from different locations a great number of tree trunks covered with Cattleya intermedia, among which a plant stood out, different from the others because of its color and form of the flowers. This Cattleya called the attention of Francisco d’Aquino, a good friend of Mr. Valadares and one of the most important orchidophils of his time. Seeing Aquino’s interest in this plant, Valadares presented it to him. Aquino cultivated it for eight years and some time later made several divisions of it, distributing them among his fellow orchid collectors. As can be seen, the few existing specimens are descendants of this first plant. Being Aquino a collaborator of the great Brazilian scientist, Dr. Barbosa Rodrigues, at the time Director of the Botanical Garden in Rio de Janeiro, he gave him one of the divisions, which was recognized by Barbosa Rodrigues as a new species from the state of Rio Grande do Sul and described and illustrated by him in his work Plantas novas cultivadas no Jardim Botanico do Rio de Janeiro” (Kley 1942:120) (Fig. 69).

These lines were written in 1891. Some 30 years later, Schlechter began preparing his orchid flora of Rio Grande do Sul. He wrote then: “to achieve my goal, I made contact with various orchid lovers in Porto Alegre. Through their collaboration I was able to start corresponding with a few collectors. Above all, I must thank Mrs. L. Burger and Francisco Aquino, for the eagerness with which they promoted my interests”.

Aquino sent an important number of orchid specimens to Schlechter, of which many were proven as new to science. With his own specimens, Aquino sent a number of orchids collected by Burger - of whom we could only retrieve the initial and family name - which are all labeled Burger [xxx] in collectionis Aquino. Curiously the specimens collected by Burger outnumber those of Aquino by at least 7:1. This means that the main collector was undoubtedly L. Burger.

Only 2 orchid specimens collected by Aquino and described by Schlechter were new to science: Pleurothallis aquinoi (Aquino IV) and Polystachya micrantha (Aquino XXII).