Introduction

Marine reptiles such as sea snakes play an important trophic role in marine ecosystems (Brischoux & Lillywhite, 2013; Voris, 1972) and their distribution encompasses mainly tropical waters (Tu, 1988). The yellow-bellied sea snake, Hydrophis platurus (previously: Pelamis platurus), is the most widely distributed hydrophiid snake in the world (Hernández-Camacho et al., 2005; Lomonte et al., 2014; Quiñones et al., 2014) and is the only pelagic species (Brischoux & Lillywhite, 2011; Heatwole, 1999; Sheehy et al., 2012). The presence of this species has been confirmed in the Eastern Tropical Pacific, from the coasts of Mexico to northern Peru (Brischoux & Lillywhite, 2011; Graham, Rubinoff, & Hecht, 1971; Quiñones et al., 2014).

The movement patterns of H. platurus remain largely unknown. Marine currents (Kropach, 1971) and sea surface temperature (SST) (Quiñones et al., 2014) are environmental parameters related to their distribution patterns, with ocean currents playing an important role in the the movement of H. platurus (Brichoux et al., 2016). Slicks are formed when surface currents converge and snakes passively drift within these slicks (Kropach, 1971). The abundance of snakes on a slick can be influenced by the quantity of flotsam found within the slick (Brischoux & Lillywhite, 2011). The yellow-bellied sea snake is a ‘passive surface drifter’ and is often transported by currents to locations where it is not considered resident (Dunson & Ehlert, 1971).

As an ectotherm, sea surface temperature (SST) limits the species’ distribution to a minimum of 18 °C, since locomotor abilities and feeding are inhibited or cease at lower SSTs (Heatwole, Grech, Monahan, King, & Marsh, 2012); and to a maximum of 33 °C (Dunson & Ehlert, 1971). These SST ranges prevent the species from colonising regions such as the Atlantic Ocean ( Lillywhite et al., 2018; Quiñones et al., 2014) and the Pacific coast of South America, where strong upwelling of cold water limits their distribution (Dunson & Ehlert, 1971). Waters off Central America represent optimal thermal conditions for the yellow-bellied sea snake, since mean monthly temperatures of > 25 °C are the minimum required for feeding (Hecht, Kropach, & Hecht, 1974). Although H. platurus has a natural preference for offshore waters, the species has been also recorded in shallow coastal waters (Heatwole, 1999; Hecht et al., 1974). Its dependence on freshwater to avoid water deficits due to dehydration during dry season may explain their coastal distribution in Costa Rica (Lillywhite et al., 2010), but its still controversed (Lillywhite et al., 2014; Lillywhite et al., 2019).

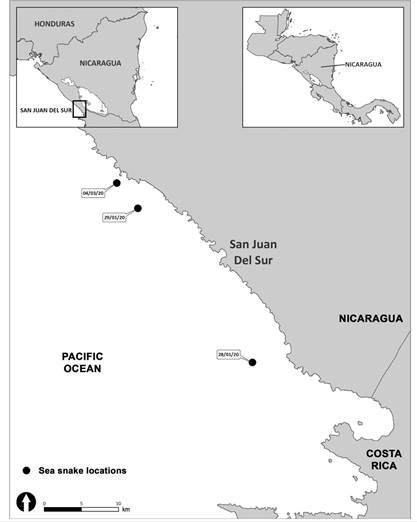

Daylight is a determining factor in the surfacing behavior of H. platurus; it shows a preference for high light levels (Brischoux & Lillywhite, 2011) and is not often observed at the sea surface at night (Brischoux & Lillywhite, 2011); however the latter needs further investigation due to a lack of samples. In Central America, H. platurus has been reported in the Gulf of Fonseca, Honduras (McCranie & Gutsche, 2016; Solis et al., 2014), the Pacific coast of Costa Rica (Bolaños et al., 1974; Tu, 1976; Tu & Salafranca, 1974), the Pacific coast of El Salvador (Hidalgo, 1980) and the Gulf of Panama (Guinea et al., 2017; Kropach, 1971; Vallarino & Weldon, 1996). Yellow-bellied sea snakes have been frequently reported in the Pacific coast of Nicaragua between the Gulf of Fonseca (Chinandega) and San Juan del Sur (Rivas), however, observations are limited to beach strandings and no data is available on the marine occurrence of this species. To date, no marine records have been published on the presence of the yellow-bellied sea snake in Nicaragua. Here, we report, for the first time, the presence of H. platurus in the southwestern Pacific waters of Nicaragua, offering additional insights into distribution and behavioral patterns of this marine snake in the Eastern Tropical Pacific.

Materials and methods

Data were gathered during systematic boat-based surveys from January to mid-March 2020. Surveys were conducted using a 6 m length fiberglass boat, between 0800 and 1700 h daily. When the yellow-bellied sea snake was found, the following data were collected: date, time, Global Positioning System location, sea surface temperature (SST, Hecht thermometer), sea state (using the Beaufort scale), and swell categorized as either Low (L), less than one meter; Medium (M) 1-2 m; and High (H) more than two meters (Table 1). Photographs were taken using a DSLR camera with a 55-300 mm lens, and were used for specimen identification based upon standard morphological characteristics (see below). Maps indicating sighting locations were generated with ArcGIS. Distance from the nearest point on the coast was measured for each sighting location using the line tool in ArcGIS.

Table 1 Overview of field records of the yellow-bellied sea snake (Hydrophis platurus) off the South-West Pacific coast of Nicaragua, including sighting date and time, latitude and longitude, SST, Beaufort scale and swell, and distance from the coast

| Date | Time | Latitude | Longitude | SST (°C) | Picture | Sex | Beaufort | Swell | Distance from coast (km) |

| 28 Jan 2020 | 12:04 | 11°7’21.698” N | 85°50’29.198” W | 27 | No | Uk | 1 | L | 4.6 |

| 29 Jan 2020 | 16:24 | 11°18’39.802” N | 85°58’54.199” W | 28 | Fig. 1a | Uk | 1 | L | 3.8 |

| 04 Mar 2020 | 16:05 | 11°20’30.699” N | 85°00’27.698” W | 25 | Fig. 1b | Uk | 4 | L | 1.4 |

SST = Sea Surface Temperature, Uk = unknown.

Results

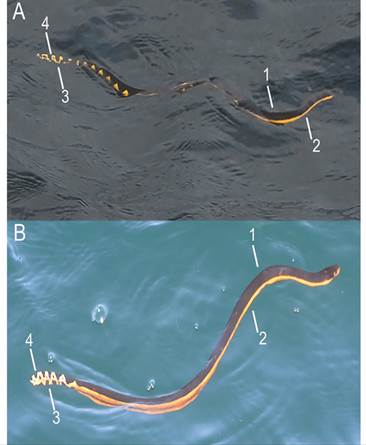

Three field observations of yellow-bellied sea snakes were made on 28 and 29 January 2020 (photographed) and 04 March 2020 (photographed) (Fig. 1). Based on photographic observations, the following morphological features confirmed the identification of the species: 1) Black dorsal side extending from the head to the tail with variations in the dorsal band pattern; 2) Yellow ventral side extending from the head to the tail; 3) Dark spots on the tail; 4) Paddle-shaped tail. Both photographed individuals were bi-colored and displayed two distinct color patterns (Fig. 2). Sex and size could not be inferred or measured from the photographs. On the three occasions, the yellow-bellied sea snake was swimming alone at the surface and moved southwards. Each individual dived after traveling at the surface for a few minutes. Sightings occurred in a range of 30 km from each other and 3.3 km from the coast. The average SST was 26.6 °C (± 1.25 SD, N = 3) (Table 1). Swell was low on all occasions and the Beaufort sea state ranged between 1 and 4 (Table 1).

Discussion

Our observations confirm the presence of yellow-bellied sea snakes in shallow coastal waters off the southwestern coast of Nicaragua. Extensive variation in color patterns of this species has been documented, with almost completely black and entirely yellow specimens represented at each end of the spectrum (Solórzano, 2011). In addition, the patterns of the black dorsal band vary from straight to completely curved, and spots may be completely absent (Tu, 1976). All three of our sighted individuals were bi-colored, as also observed in other Central American regions (Hidalgo, 1980; Tu, 1976).

The bi-color pattern is commonly observed in juvenile yellow-bellied sea snakes, which develop the tri-color pattern during ontogeny (Tu & Salafranca, 1974). The observation made on the 28 January 2020 (Fig. 2A) displayed a saw-edged dorsal band which matches specimens found in El Salvador and Costa Rica (Hidalgo, 1980; Tu, 1976), while the observation made on the 04 March 2020 (Fig. 2B) did not display the dorsal pattern which is consistent with juvenile descriptions of specimens found in Costa Rica (Tu, 1976).

Fig. 2 Morphological features for identification of the yellow-bellied sea snake include: 1) Black dorsal side 2) yellow ventral side 3) Dark tail spots 4) Paddle-shaped tail. A) Individual photographed on 29 January 2020 with a partially straight dorsal band; B) Individual photographed on 04 March 2020 with a straight dorsal band with the exception of subcaudal portion. Color pattern as described by Tu (1976).

The mean measured SST of 26.6 °C falls within the range of optimal feeding temperatures (Hecht et al., 1974). Although our observations of solitary snakes were made in such conditions, the snakes were probably not involved in feeding behaviors, due to the absence of slicks with which they tend to associate for feeding (Dunson & Ehlert, 1971; Kropach, 1971). The observation of solitary snakes not associated with slicks is commonly observed in Panama (Kropach, 1971) and Costa Rica (Brischoux & Lillywhite, 2011).

Our sightings of yellow-bellied sea snakes occurred within 5 km of the coast which coincides with other records in neighboring countries (Solòrzano, 2004; Tu, 1976). The underlying factors for the coastal occurrence of this offshore species remains largely unclear, even if it was suggested that their reliance on freshwater could be responsible for the coastal distribution (Lillywhite et al., 2010) recent studies did not support this hypothesis (Lillywhite, 2019). All our field observations were made in the afternoon, which contrasts with findings in the Papagayo Gulf, Costa Rica, where snakes were not observed in the afternoon (Tu, 1976).

Even though yellow-bellied sea snakes are frequently reported on the beaches of San Juan del Sur and surrounds, no previous report on their marine distribution has been made. The present paper presents, to the best of our knowledge, the first marine report of this species in the Pacific waters of Nicaragua. The presence of non-feeding, lone, bi-colored individuals in coastal areas can help researchers understand the ecology and movement patterns of the species off Central America in the Eastern Tropical Pacific. Additional research is needed to understand the correlation between environmental parameters, such as oceanic currents, and the distribution patterns of the yellow-bellied sea snake in Nicaragua.

Ethical statement: authors declare that they all agree with this publication and made significant contributions; that there is no conflict of interest of any kind; and that we followed all pertinent ethical and legal procedures and requirements. All financial sources are fully and clearly stated in the acknowledgements section. A signed document has been filed in the journal archives.

uBio

uBio