1. Introduction

Both family structures and work environments have undergone deep transformations in recent years. For instance, a stronger participation of women in the labor market has modified traditional family models by increasing the number of dual-earner and single-parent households, and by restructuring the distribution of family roles (Munn & Chaudhuri, 2016). Furthermore, the appearance of more complex and demanding jobs has posed increasing demands on employees, resulting in higher levels of distress and burnout (Mauno et al., 2019). Finally, the emergence of new information and communication technologies has forced workers to 'stay connected' at all times and from any place, blurring the lines between work and personal life (Ninaus et al., 2021). Changes like these have certainly created additional challenges for employees in terms of managing work and non-work demands, thus increasing scholarly and managerial interest in work-life interaction as a field of study and intervention (Powell et al., 2017).

Although work-life interaction can have both positive and negative effects on individuals' well-being (Friedman & Greenhaus, 2000), most studies within this research stream have been conducted from a conflict perspective, that is, they have mostly focused on the interference that occurs when the demands of a role or domain make it difficult for the individual to fulfill the expectations and responsibilities of another role or domain (Allen et al., 2000; Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). In this sense, work-life conflict (hereafter, WLC) has been described as a highly stressful, exhausting experience that tends to consume the economic, psychological and physical resources of individuals, which is likely to affect their performance levels and quality of life in both work and non-work domains (Lu & Kao, 2013). It is not surprising, then, that numerous studies have reported that WLC tend to result in negative outcomes, including, for instance, lower levels of job satisfaction (Benligiray & Sönmez, 2012), family satisfaction (Kalliath et al., 2017) and life satisfaction (Rupert et al., 2012).

Despite the fact that WLC is usually perceived as a consuming and exhausting experience, there is evidence that work-life interaction is also beneficial for individuals as it may improve their performance and positive effect in both work and non-work domains (Frone, 2003; Wayne et al., 2007). Indeed, numerous studies have reported that work-life interaction may promote positive dynamics between work and personal life (Carlson et al., 2006). In this regard, Greenhaus and Powell (2006) used the term work-life enrichment (hereafter, WLE) to describe the extent to which individuals' experiences in a particular domain contribute to increase their quality of life in another domain. Thus, since WLE facilitates the accumulation of resources that ultimately improve role performance in both work and non-work domains, it has been associated with many beneficial outcomes, including, for instance, higher levels of job satisfaction (McNall et al., 2009), family satisfaction (Carlson et al., 2006) and life satisfaction (Yasir et al., 2019).

It should be noted that while WLC and WLE have been mostly studied independently, there is evidence that individuals often experience both phenomena simultaneously (Bansal & Agarwal, 2020). Given that none of these processes in isolation provide a complete understanding of the dynamics underlying work-life interaction (Bansal & Agarwal, 2020), it is necessary to understand which factors and processes are most effective at managing WLC and WLE. In this regard and following a demand-resources perspective (Demerouti et al., 2001), individuals may have at least two mechanisms to improve work-life interaction. On the one hand, employees may possess certain personal characteristics (e.g., self-efficacy) or skills (e.g., networking abilities) that could be used as personal resources to facilitate the idiosyncratic negotiation of special working conditions (e.g., flexible hours) with their employers (Marino et al., 2022) and, thus, improve work-life interaction (Bal & Rousseau, 2016). However, since not all individuals are in the same position to negotiate idiosyncratic employment conditions, organizations provide their employees with a complementary and standardized set of resources that are often available to many employees, frequently known as work-life policies or organizational work-life initiatives (hereafter, OWLI). In this context, OWLI refer to specific terms, arrangements, working conditions or benefits that organizations grant to their employees to improve work-life interaction by allowing them to engage in both work and non-work domains and to manage their roles, interests and responsibilities in life (Morris et al., 2011; Ollier-Malaterre, 2009; Poelmans & Beham, 2008).

Despite the large body of research that has examined the impact of these initiatives on employees' outcomes (Ali et al., 2015; Moen et al., 2016, Gutiérrez et al., 2022), there is still limited evidence of how they simultaneously contribute to mitigate WLC and promote WLE (Kelly et al., 2008; Wayne et al., 2020). Therefore, this study responds to this call by examining the role of OWLI in work-life interaction in a sample of Argentinian employees from different industries. To address the effects of WLC and WLE the study focuses on job satisfaction, defined as an affective response towards the job as a whole (for an in-depth discussion, see Pujol-Cols and Dabos, 2020). In this context, job satisfaction remains one of the most widely studied constructs in organizational behavior (for a review, see Pujol-Cols & Dabos, 2018) and has been shown to be affected by work-life dynamics (Benligerty & Sönmez, 2012; Gutiérrez- et al., 2022; McNall et al., 2009). More specifically and drawing on the propositions of the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989), the article posits that OWLI will buffer the negative effects of WLC by preventing resource loss and will foster the positive effects of WLE by facilitating resource accumulation. This research, then, contributes to the literature on work-life interaction by providing empirical evidence of the role of OWLI in individuals' responses to work-life interaction. Furthermore, the findings of this study are fundamental to understand how OWLI improve employees' job attitudes by simultaneously mitigating WLC and promoting WLE.

2. Theoretical background and hypothesis development

2.1 Work-life interaction and job satisfaction

Work-life interaction is a field of study that examines the mechanisms through which the experiences in the domains of work and personal life interact with each other and influence individuals' attitudes, behavior and well-being (Aryee et al., 1999). Traditionally, work and family domains have received the most attention in literature, as these were thought to be the roles in which individuals invested most of their time and resources (Powell et al., 2019). It should be noted that this assumption was later challenged by more recent evidence showing that the nature of the interactions between work and personal life are much more complex as people may face additional problems and difficulties that are not exclusively related to, for instance, the family domain (Kelliher et al., 2018). Consequently, researchers began to use the term work-life (or work-nonwork) interaction to reflect the dynamics underlying the multiple activities that individuals can engage in outside the family domain. The present study follows this approach in an effort to contemplate the different realities of modern societies (e.g., single parent or dual-earner households, assembled families, families without children or caregiving responsibilities, and so forth) and the various domains (e.g., leisure, community, church, sports, self-actualization, or volunteer activities) involved in the work-life interaction construct (Casper et al., 2018; Wilson & Baumann, 2015).

Moreover, extant research has acknowledged that work-life interaction can occur in two directions (Carlson & Frone, 2003), that is, work experiences may be affected by workers' personal lives (i.e., life-to-work direction) and individuals' personal lives may be affected by their work experiences (i.e., work-to-life direction). To provide an example, work distress may prevent individuals to fulfill their family roles effectively and, at the same time, happy experiences at home may lead to more positive mood states and, thus, improve performance levels at work. That being said, and despite the fact that work-life interaction is indeed a bidirectional phenomenon, this study in particular focuses on the work-to-life direction because past literature has shown that work-related outcomes, such as job satisfaction, are more likely to be influenced by organizational initiatives (Grzywacz & Butler, 2005; Wayne et al., 2013).

Furthermore, studies on work-life interaction initially drew on the assumption that work and personal life were two separate, incompatible domains that competed for individuals' resources. In this context, the term WLC was introduced to reflect a situation that arises when the demands of one role or domain make it difficult for the individual to meet the expectations and responsibilities of another role or domain (Dierdorff & Ellington, 2008; Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). In this regard, it is worth mentioning that many studies have shown that WLC is usually perceived as a highly demanding and exhausting experience that tends to drain individuals' economic, psychological, and physical resources over time, which is likely to lead to feelings of distress and, as a consequence, to negatively affect their performance levels and quality of life in both work and non-work domains (e.g., Allen et al., 2000; Lu & Kao, 2013).

It should be noted that the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989) provides a useful framework to understand the effects of WLC on individuals' job attitudes. In the context of this theory, a resource is conceptualized as an asset that can be used when necessary to solve a problem or face a challenging situation (e.g., time available, social support, professional skills) (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). The COR theory argues that individuals have a limited amount of resources to perform various roles, thus being motivated to seek, obtain and protect those resources that are highly valued by them (ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). From this perspective, the process of facing a demanding situation is usually viewed as an unpleasant and destabilizing experience, caused by the fear of a potential loss of resources or by the actual loss of them (Demerouti et al., 2004). When individuals struggle with the demands from multiple roles and domains that either threaten or drain a scarce, valuable set of resources, they tend to experience psychological distress, which is likely to lead to negative attitudes, including lower levels of satisfaction towards the job (Zhao et al., 2018). Based on this evidence, the following hypothesis is established:

H1: WLC will be negatively related to job satisfaction

Despite the fact that studies within this research stream have consistently demonstrated that WLC is likely to damage individuals' well-being, numerous scholars have started to call for a more positive approach to the study of work-life interaction as a way to capture the synergic effects that may also occur between both domains. In this sense, though work-life interaction may often cause WLC, some studies have suggested that it may also create many benefits for individuals. In this regard, WLE is perhaps the most widely used concept to describe positive work-life interactions, reflecting the extent to which workers' experiences in one domain improve their performance in another domain (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006; McNall et al., 2009). The concept of WLE is based on an expansionist way of viewing life roles (Marks, 1977) that proposes that individuals' participation in multiple domains (work or otherwise) provide them with additional resources, such as a higher self-esteem, an increasing income, new skills, or many other benefits, that ultimately enhance their experiences, quality of life or performance levels in other spheres of life (Friedman & Greenhaus, 2000).

The COR theory also proposes that, when performing specific roles, individuals not only are required to invest some of their resources, but also can accumulate new ones through positive gain spirals or resource caravans. The idea behind the concept of caravan is that resources tend to 'travel together', which means that the process of obtaining certain resources increases individuals' current stock of them and, at the same time, places them in a better position to obtain new resources in the future (ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). From this perspective, the concept of enrichment suggests that the resources accumulated while performing a role in a particular domain can be used by the individual to enhance their experiences or performance levels in other domains of life (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). To provide an example, participation in the work domain often provides individuals with many opportunities to develop problem-solving skills that can be applied to boost their performance levels on the job and also to enhance their quality of life in, for instance, the family domain (Rothbard, 2001). In this sense, by engaging in work roles, individuals are more likely to increase their repertoire of competencies, which may not only reduce the negative effects of WLC, but also improve their overall performance of other roles in non-work domains. Further, such process may help individuals to feel personally fulfilled, which may lead to better mood states and more positive attitudes towards the job (Ruderman et al., 2002).

Based on the rationale discussed above, this paper proposes that individuals' participation in a particular domain (e.g., work) will enhance their experiences in other domains of life (e.g., family) by fostering resource accumulation through positive gain spirals. Although WLE has received considerably less attention than WLC in the empirical literature, as discussed previously in this paper, there is some evidence that WLE often leads to more positive outcomes, such as increasing levels of job satisfaction (Tang et al., 2014). Drawing on the theoretical propositions explained above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: WLE will be positively related to job satisfaction

2.2 OWLI and their impact on work-life interaction

The successful management of work-life interaction has become a top priority for many organizations around the world given its strong implications for individuals' job attitudes, performance, and well-being (Murphy & Zagorski, 2013). Although some aspects of work-life interaction are usually regulated by the labor legislation of each country (e.g., maternity leaves), organizations have begun to implement a complementary set of policies, practices or interventions intended to help their employees to successfully balance the demands from both work and personal life. These practices are usually known as organizational work-life initiatives and consist of specific terms, arrangements, working conditions or benefits that organizations grant to their employees to allow them to engage in work and non-work domains and to manage their roles, interests and responsibilities in life (Morris et al., 2011; Ollier-Malaterre, 2009; Poelmans & Beham, 2008). In general, most OWLI include aspects related to job flexibility (e.g., time flexibility, location flexibility, flexible employment contracts) or many other benefits (monetary, health-related or otherwise) that organizations provide to their employees to improve work-life interaction (Ali et al., 2015).

Most OWLI are designed to reduce the distress experienced by employees in response to WLC. However, it should be noted that some of these practices can also promote WLE (Baral & Bhargava, 2010). For instance, flexibility-based initiatives, which involve redesigning various aspects of the job by providing individuals with greater autonomy and by encouraging them to apply a wider variety of skills, can surely be a source of satisfaction, sense of identity, and personal fulfillment (Flynn & Tannenbum, 1993). In addition to these motivational effects, flexibility-based practices may create additional opportunities for employees to increase their repertoire of competencies (e.g., time-management skills, self-confidence) and improve their performance and positive affect in the work domain (Friedman & Greenhaus, 2000). Some of these competencies may be even transferred by the individual to facilitate their performance in other non-work domains and thus enhance their experiences of WLE (Baral & Bhargava, 2010).

The impact of OWLI on work-life interaction can be explained through the lenses of the Job Demands-Resources theory. This theory posits that job resources affect employees' job attitudes in two ways. On the one hand, they buffer the negative impact of job demands by providing individuals with the time, knowledge, information, tools or emotional support needed to respond to the exhausting and stressful situations they face inside and outside the organization. On the other hand, job resources can also lead to positive experiences as they are functional to reaching goals, are associated with positive mood states, and stimulate personal growth. Based on these arguments, this paper proposes that OWLI are indeed a set of job resources with high potential to improve work-life interaction and, as a result, employees' work attitudes (Kossek & Ozeki, 1998; Premeaux et al., 2007).

It should be noted that previous research has examined the effects, mainly direct, of these practices on work-life interaction. For instance, some studies have reported negative relationships between work-life policies and WLC (Allen, 2001) and positive relationships between these initiatives and WLE (Hill et al., 2004). Nevertheless, it should be noted that various studies have also obtained mixed or inconsistent results (Brough et al., 2005) or have failed to trace statistically significant relationships between these phenomena (Batt & Valcour, 2003). It follows that research that provides empirical evidence of the role of OWLI in work-life dynamics and their effects on individuals is thus fundamental to better understand which initiatives in particular are most effective at mitigating WLC and/or promoting WLE.

Then, the present study responds to this research call and proposes that OWLI will contribute to buffer the relationship between WLC and job satisfaction, so that the effects of WLC on job satisfaction will be less negative for those individuals who use OWLI on a regular basis. Likewise, this study argues that OWLI will amplify the relationship between WLE and job satisfaction, so that the positive effects of WLE on job satisfaction will be greater for those individuals who use these practices more frequently. Although no research to date has empirically examined the relationships proposed in this paper, the COR theory provides a useful framework to understand these mechanisms. For starters, OWLI, such as flexible schedules or location flexibility, make it easier for employees to balance the demands from work and, for example, family, being less prone to experiencing the exhaustion and strain caused by the sustained investment of physical and psychological resources (Allen et al., 2013). In this sense, by reducing the interferences between both sets of domains and by making the experience of conflict to be lived as less stressful, it is plausible that OWLI buffer the negative effects of WLC on job satisfaction. Moreover, since OWLI allow employees to engage in other non-work roles, such as training and social activities, and that this participation often leads to a resource accumulation (Hobfoll, 1989), it is highly likely that these initiatives also contribute to foster the positive effects of WLE on job satisfaction trough positive gain spirals.

Drawing on the theoretical rationale presented above, it is expected that the extent to which employees make use of these job resources, namely OWLI, will contribute to buffer WLC and foster WLE by: (a) reducing resource loss and/or (b) amplifying resource accumulation. Thus, the following hypotheses are established:

H3: The use of OWLI will mitigate the negative effects of WLC on job satisfaction.

H4: The use of OWLI will amplify the positive effects of WLE on job satisfaction.

Figure 1: Proposed relationships among the study variables.

3. Method

3.1 Participants

Data were collected in a non-random sample of 362 individuals who worked in organizations from different industries in a metropolitan area of Buenos Aires, Argentina (see Table 1). The age of the participants ranged from 20 to 68 years, with a mean of 36.48 and a standard deviation of 8.22. Nearly 51% were male. Moreover, 41.71% of the participants reported having at least one family member under their care (96.64% of these family dependents were children). Moreover, 58.29% of the participants were married or living with a life partner, 35.64% were separated or divorced, 5.25% were single and the remaining 0.83% were widowed. Regarding their educational level, 16.57% had a high school diploma, 9.94% had post-secondary education, 43.09% were college graduates, and 30.39% had a postgraduate degree. Participants' tenure in the organization varied between 6 months and 46 years, with a mean of 7.48 and a standard deviation of 7.46. Finally, 41.44% of the individuals who participated in the study reported working in a hybrid model, 40.88% of them worked in an office-based job, and the remaining 17.68% worked remotely from home.

Table 1: Characteristics of the participants

| M | DE | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 36.48 | 8.22 | |

| Tenure in the current organization | 7.48 | 7.46 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 50.55 | ||

| Female | 49.45 | ||

| Relationship status | |||

| Married or living with a life partner | 58.29 | ||

| Separated or divorced | 35.64 | ||

| Single | 5.25 | ||

| Widowed | 0.83 | ||

| Educational level | |||

| High school diploma | 16.57 | ||

| Post-secondary education | 9.94 | ||

| Undergraduate degree | 43.09 | ||

| Postgraduate degree | 30.39 | ||

| Working system | |||

| Office-based model | 40.88 | ||

| Hybrid model | 41.44 | ||

| Fully remote model | 17.68 |

3.2 Procedure

Participants were contacted using a networking approach (Heckathorn & Cameron, 2017). This sampling strategy represents a standard procedure in organizational behavior research as it offers many benefits including, for instance, higher response rates due to an increase in individuals' willingness and motivation to participate in the study (Pujol-Cols, 2021). The data reported here were collected from August to October, 2022. The procedure began by recruiting a group of individuals who were graduates or active students of a part-time Master of Business Administration (MBA) program. Eligible participants were required to work under a formal employment relationship and to report a minimum tenure of six months so that they had the chance to use some of the OWLI that were available to them in the organization. In addition to completing a digital survey, they were asked to share the online invitation with some of their colleagues who might be interested in participating in the study. In compliance with international ethical standards, the participants had access to the aims of the study and were guaranteed that their responses to the survey would be held confidential. Likewise, the participants were reminded that participation was voluntary and that a signed consent form was required to participate in the study.

3.3 Variables and instruments

Unless otherwise indicated, the responses to the survey were anchored in a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Work-life conflict. This variable was measured using an adaptation of a scale developed by Pujol-Cols (2021), which is a Spanish version of Carlson et al's (2000) Work-Family Conflict Scale. Specifically, only the 9 items measuring the work-to-life conflict direction were considered. To ensure that the scale indeed examined WLC, instead of work-family conflict, we proceeded to replace those terms reflecting conflict experiences in, specifically, the family domain (e.g., "family responsibilities", "family activities") with phrases reflecting participants' experiences in a wider, life domain (e.g., "personal responsibilities", "personal activities"). An example item is "My work keeps me from my personal activities more than I would like". This scale reported a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.87.

Work-life enrichment. An adapted version of the work-to-life enrichment subscale validated by Omar et al (2015) was used. It should be noted that this instrument is a Spanish version of Carlson et al's (2006) Work-Family Enrichment Scale. To ensure that the scale indeed examined WLE, instead of work-family enrichment, we proceeded to replace those terms reflecting enrichment experiences in, specifically, the family domain (e.g., "family responsibilities", "family activities") with phrases reflecting participants' experiences in a wider, life domain (e.g., "personal responsibilities", "personal activities"). An example item is "My involvement in my work puts me in a good mood and this helps me to be better in other roles of my personal life". The internal consistency of this scale was 0.93 in this study.

Job satisfaction. Although some previous studies have measured job satisfaction by focusing on its cognitive aspects (i.e., cognitive job satisfaction), this paper followed an affective point of view by defining job satisfaction as an emotional response towards the job as a whole (i.e. affective job satisfaction; see Fisher, 2000). In this sense, job satisfaction was measured with a Spanish version of the Brief Index of Affective Job Satisfaction (Thompson & Phua, 2012) developed by Pujol-Cols and Dabos (2020). It consisted of 4 items (e.g., "I find real enjoyment in my job") and reported a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.87.

OWLI. An ad-hoc scale was designed to assess these practices appropriately in the Argentinian socio-cultural context. As a preliminary step, a theoretical and methodological review was conducted to identify the set of OWLI used most frequently by organizations to improve work-life interaction. The scale included three major types of OWLI that have been widely considered in the work-family literature (Perry-Smith, & Blum, 2000; Poelmans et al., 2003): flexibility policies (e.g., "Flex time, being able to adapt my working schedule to my personal needs"), family-friendly policies (e.g., "Extended leaves and additional vacation time, that exceed those established in current laws and regulations") and benefit-based policies (e.g., "Training and education programs that increase my personal competencies"). The final scale comprised 13 items that measured how frequently the participants used a particular initiative. Moreover, and drawing on a previous study by Pasamar (2015) that suggested the possible existence of gaps between the availability of work-life benefits and the actual use of them by individuals, a "not available" option was included to identify those situations in which the participants had no chance to use a particular initiative only because it was not available in the organization. The internal consistency was .76 for the subscale of flexibility policies, .69 for the subscale of family-friendly policies, and .85 for the subscale of benefit-based policies.

Control variables. The findings were controlled for a number of variables that have influenced work-life interaction in previous research (Allen et al., 2013; Grzywacz & Butler, 2005), such as gender, age, education, marital status, number of children, dominant working system and level of seniority.

3.4 Data analysis

The hypotheses of the study were tested using multiple regression analysis. As a preliminary step, a series of tests were conducted to ensure that the data complied with the basic assumptions of multiple regression analysis (e.g., homoscedasticity). Moreover, to rule out the possibility that the results were affected by common method bias, Harman's one factor test was performed following the procedure described in Podsakoff et al (2003). The findings showed that the first factor explained only 25.29% of the total variance (which is lower than the conventional level of acceptance of 50%), suggesting that the results were not significantly affected by common method bias.

4. Results

4.1 Preliminary psychometric analysis

Since the OWLI scale (see Appendix) was developed for the purposes of the study, we proceeded to examine its dimensionality by conducting an exploratory factor analysis with a varimax, orthogonal rotation (KMO = 0.83, Bartlett's test of sphericity was statistically significant at the p < 0.001 level). This process, along with a sensitivity analysis of Cronbach's alpha coefficients, allowed us to reduce the original scale from 15 to 13 items. As shown in Table 2, the results of the exploratory factor analysis of the 13 items (KMO = 0.87, Bartlett's test of sphericity was statistically significant at the p < 0.001 level) revealed that the OWLI scale exhibited a three-dimensional structure: flexibility policies (e.g., "Flex time, being able to adapt my working schedule to my personal needs"), family-friendly policies (e.g., "Extended leaves and additional vacation time, that exceed those established in current laws and regulations") and benefit-based policies (e.g., "Training and education programs that increase my personal competencies"). The factor loadings of most items were greater than 0.70 and the three core dimensions showed average variance extracted values that exceeded 0.60, which indicated appropriate levels of convergent validity (Hair et al., 2010).

Table 2: Dimensionality of the OWLI scale (rotated factor solution)

Note. KMO = 0.87. Bartlett's test of sphericity, X 2 (78) = 1839.30, p < 001

4.2 Descriptive analysis, reliability and correlations among variables

Means, standard deviations, reliability coefficients and correlations among the variables of study are presented in Table 3. Firstly, the participants reported experiencing moderate to high levels of WLE (M = 3.74, SD = 0.76) and, to a comparatively lesser extent, moderate levels of WLC (M = 2.87, SD = 0.86). The results also showed moderate to high levels of job satisfaction in the sample (M = 3.55, SD = 0.86). Moreover, the correlations among the study variables were found to be moderate in most cases and none of them exceeded the standard value of 0.70, indicating that the discriminant validity of the study was not compromised.

Table 3: Means, standard deviations and correlations between variables.

Note. N = 362. * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01. Scale reliabilities (alpha coefficients) are on the main diagonal in bold.

4.3 Hypothesis testing

The hypotheses were tested through multiple regression analysis (see Table 4). As a preliminary step, both the independent variables (WLC and WLE) and the moderator (OWLI) were mean-centered (Cohen et al., 2003) and interaction terms were created between each independent variable and the moderator. Furthermore, a set of dummy variables were created to measure employees' working system, in which having an office-based job was the base group.

As shown in Table 4, the model explained about 48% of the variance in job satisfaction. None of the control variables showed a significant effect on the dependent variable. The first hypothesis proposed that there would be a negative relationship between WLC and job satisfaction. The results revealed that, though the effects of WLC were indeed negative, they were not statistically significant, not supporting Hi. Regarding the second hypothesis, which argued that those individuals who experienced higher levels of WLE would be more satisfied with their job, the results showed that WLE was indeed found to be positively and significantly related to job satisfaction (ß = 0.74, p < 0.01), supporting H2. Moreover, none of the OWLI displayed a direct and significant effect on job satisfaction.

In addition to the direct effects of work-life interaction, this study proposed that OWLI would exert a moderating effect on the relationship between WLC and WLE, and job satisfaction. In other words, it was argued that these initiatives would mitigate the negative effects of WLC and foster the positive effects of WLE on satisfaction. In this regard, the study was able to trace a moderating effect of only one out of three types of initiatives. In this sense, the findings indicated that flexibility initiatives indeed moderated the WLC-job satisfaction relationship (ß = 0.07, p < 0.10) and the WLE-job satisfaction relationship (ß = 0.08, p < 0.10), but no moderating effects were found in the case of family-friendly policies and benefit-based policies.

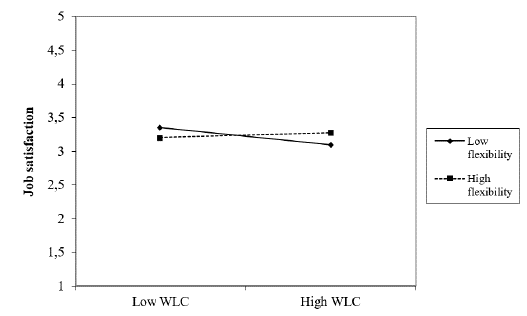

To evaluate whether the significant interactions provided support to H3 and H4, simple slope tests were performed and the slopes were plotted at one standard deviation below and above the mean (Cohen et al., 2003). The results showed that the negative effect of WLC on job satisfaction was only significant when the use of flexibility initiatives was low (ß = -0.15, t = -2.44, p < 0.05), thus providing partial support to H3. Moreover, as shown in Figure 2, the negative effect of WLC on job satisfaction was greater when the use of flexibility initiatives was low, demonstrating that such initiatives play a relevant role in reducing the detrimental consequences of WLC on employees.

Figure 2: Interactive effects of flexibility initiatives in the relationship between work-life conflict and job satisfaction

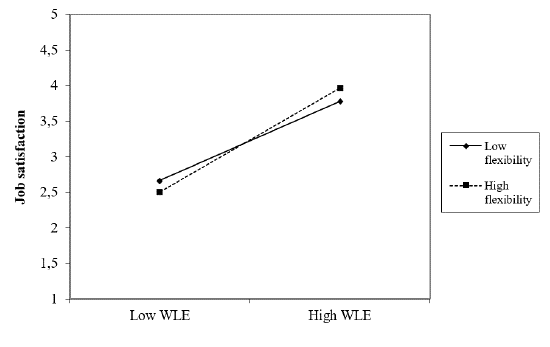

Regarding WLE, the results of the simple slope tests indicated that the positive effects on job satisfaction were statistically significant at both levels of the moderating variable. In other words, the effects of WLE on job satisfaction were significant not only when the use of flexibility initiatives was low (ß = 0.62, t = 8.07, p < 0.01) but also when its use was high (ß = 0.85, t = 9.79, p < 0.01). As depicted in Figure 3, the results revealed that the positive effects of WLE on job satisfaction were stronger when employees reported a high use of flexibility initiatives, demonstrating the fostering role of such initiatives in individuals' positive responses to WLE and supporting H4.

Figure 3: Interactive effects of flexibility initiatives in the relationship between work-life enrichment and job satisfaction

Table 4: Multiple Regression Results

| Dependent variable: Job Satisfaction | Model | |

|---|---|---|

| Predictors | ß | RSE |

| 1. Control variables | ||

| Age | .01 | .00 |

| Female | .13 | .07 |

| Family dependents | -.03 | .08 |

| Lives with life partner | .07 | .09 |

| Hybrid work mode | .10 | .08 |

| Remote work mode | .01 | .14 |

| 2. Mean Effects | ||

| Work-life conflict | -.06 | .04 |

| Work-life enrichment | 74*** | .06 |

| Flexibility | .01 | .05 |

| Family support | .01 | .05 |

| Benefits | .03 | .04 |

| 3. Interactions | ||

| Conflict x Flexibility | .07* | .04 |

| Conflict x Family support | -.02 | .05 |

| Conflict x Benefits | .02 | .04 |

| Enrichment x Flexibility | .08* | .04 |

| Enrichment x Family support | -.02 | .08 |

| Enrichment x Benefits | -.02 | .06 |

| Intercept | 3.23*** | .17 |

| R2 | 48*** | |

Note. N = 362. * p < 0.10 ** p < 0.05 *** p < .01. Since the Breusch-Pagan test for heteroskedasticity was statistically significant, which indicates that some level of heteroskedasticity were detected, robust standard errors (RSE) were calculated, x 2 (1) = 21.83, p < 0.01

5. Discussion

With the purpose of advancing scholarly understanding of the dynamics underlying employees' responses to work-life interaction, the present study examined the role of OWLI in the relationship between work-life interaction and job satisfaction. In doing so, the findings responded to recent calls to further investigate both WFC and WFE simultaneously and to adopt a more comprehensive approach that is not exclusively limited to the interactions between work and family domains.

To begin with, WLC did not show a significant direct effect on job satisfaction. Although previous research has found evidence indicating that WFC, particularly the work-to-life direction, tends to be negatively related to job satisfaction (Lu & Kao, 2013), some other studies have gone one step further and highlighted the fact that these effects mostly occur in individuals with high levels of role segmentation, that is, people who set very clear boundaries between work and personal life (Zhao et al., 2018). With this consideration in mind, it is possible that the preferences for segmentation/integration of the participants may explain why a direct, negative relationship between WLC and job satisfaction was not found in this research. It is also important to emphasize the fact that the data used in this paper were collected a few months after the Covid-19 pandemic, which exposed individuals to high levels of work-life integration and somehow forced them to adjust their work-life management strategies as home working became the most dominant working system around the world (Allen et al., 2021; Koetsier, 2020). This explanation is consistent with the evidence found in this paper, as the majority of the employees who participated in the study (59.12%) worked either remotely or under a hybrid model.

Additionally, the findings of this study revealed a positive and significant relationship between WLE and job satisfaction. Although the evidence regarding the effects of WLE is much more limited when compared to that focused on WLC, the results are consistent with studies reporting that those individuals who experience higher levels of WLE tend to feel more satisfied with their job (Tang et al., 2014). Furthermore, they are in line with previous research indicating that the processes involved in WLE are more closely related to job satisfaction than those involved in WLC. Indeed, managerial interventions intending to improve work-life interaction by expanding the skills and competencies of employees seem to lead to increasing feelings of personal fulfillment and self-confidence, and, therefore, to more positive job attitudes, such as job satisfaction (Martinez-Sanchez et al., 2018).

In addition, this research demonstrated that the effects of work-life interaction on job satisfaction are different depending on the extent to which employees take advantage of the OWLI available to them. Thus, it was found that these initiatives exerted a moderating effect on the relationship between work-life interaction and job satisfaction. More specifically, the findings showed that flexibility-based initiatives indeed contributed to buffering the negative effects of WLC and to fostering the positive effects of WLE on job satisfaction. These results not only are consistent with previous research suggesting that those initiatives promoting job flexibility are more effective at achieving positive outcomes (McNall et al., 2009) than those involving granting leaves (Breaugh & Frye, 2008) or monetary rewards (Ko, 2022), but also provide further evidence of the organizational mechanisms underlying the pattern of effects of work-life interaction.

In this regard, it is worth mentioning that no statistical correlations were observed between the gender of the participants, WLC and WLE. Since gender has been shown to play a relevant role in individuals' experiences and responses to work-life dynamics, we cannot help but wonder whether our results can be considered an indicator of gender equality. In this sense, and though we believe that organizations still have a long way to go before this goal can actually be achieved in practice, the promising findings of this study could reflect the multiple initiatives that modern organizations are implementing more and more frequently to reduce gender gaps, as well as the differential exposure of female employees to psychosocial risks (Nayak & Pandey, 2022). That being said, when assessing the results of the present study, it is important to take into consideration the characteristics of the sample in which it was conducted. Indeed, the majority of the individuals surveyed here reported having post-secondary education and various years of professional experience in their fields, and this could have easily affected the relationship between gender and work-life experiences, as gender gaps are expected to be smaller in professional contexts (Pujol-Cols et al., 2024).

All in all, this research demonstrated that flexibility-based initiatives seem to affect the pattern of effects of both WLC and WLE on job satisfaction. Regarding WLC in particular, the results showed that its effects are negative and significant for those employees reporting an infrequent use of flexibility initiatives. This is in line with studies indicating that those employees who make use of OWLI tend to experience lower levels of WLC and are more prone to being satisfied with their job (Breaugh & Frye, 2008). Conversely, the positive impact of WLE on job satisfaction was found to be significant for those individuals reporting both a high and a low use of flexibility initiatives, although this positive effect was stronger when flexibility initiatives were used more frequently (i.e., the use of these initiatives seems to foster or amplify the positive effects of WLE). In this sense, the findings of the present research extended the propositions of the COR theory by showing that OWLI protect employees from resource loss and facilitate resource accumulation, which contributes to not only mitigate the detrimental impact of WLC but also promote the synergistic effects of WLE.

In addition to the theoretical contributions of this paper, the results have implications for professional practice, not only for organizations that are currently implementing OWLI but also for those planning to implement those initiatives as part of their repertoire of human resource management policies. Indeed, as one of the greatest challenges for today's organizations is to attract, develop, and retain their most qualified employees (Cappelli, 2008), an understanding of the specific roles, effects and effectiveness of OWLI certainly become essential. In this sense, and considering the results of the present study, organizations seeking to enhance job satisfaction among employees should prioritize offering them greater flexibility (e.g., time flexibility) over other types of benefits (e.g., monetary incentives) as part of their OWLI. Moreover, as this study showed, the impact of OWLI and, particularly, flexibility initiatives extends beyond their usefulness to simply 'manage' work and non-work demands, which is often associated with their mitigating role in WLC. These practices can also promote WLE by developing employees' skills, increasing their positive affect, and helping them to feel better at work. With this consideration in mind, we agree with Martinez-Sanchez et al (2018) on the fact that managers should be aware of the importance of developing a positive work environment that supports employees through practices that encourage greater enrichment between work and personal life.

6. Conclusions

This study reveals that organizational work-life initiatives, particularly those related to job flexibility, are essential in mitigating work-life conflict and promoting work-life enrichment. These findings offer a more comprehensive understanding of how organizational work-life initiatives influence employees' affective responses to work-life interaction. However, this study is not without limitations. To begin with, as one anonymous reviewer noted, the characteristics of the context in which this research was conducted could have affected some of the results, as collectivist countries may experience work-life interaction differently from individualistic countries. For example, as theorized by Allen et al (2015), people in Latin America tend to place 'familism' at the core of their cultural value system, leading them to develop strong family ties and prioritize family needs over self-interest. The presence of collectivist versus individualistic values may also influence employees' preferences for integrating or segmenting life domains. Additionally, the socio-cultural context in which this study was conducted may have shaped the availability of certain organizational initiatives, as these practices are often heavily regulated by collective labor agreements in Argentina. Although these contextual dynamics may have influenced our findings, it is worth noting that recent meta-analytic research has shown that "macro-level factors have little relationship to individual reports of work-family conflict and therefore the field may be better served by directing research efforts at individual, organizational, and/or community factors" (Allen et al., 2015, p. 98). Nonetheless, future studies could address this issue more directly by incorporating measures that reflect contextual specificities or by comparing findings across industries, countries, or regions with varying levels of trade union influence.

Furthermore, the study reported here was conducted using cross-sectional data, which means that all data were collected in a single time period and using the same instrument. Since there is evidence that most variables included in the study are not stable over time (Powell et al., 2017), future longitudinal research on this topic is very much needed. Studies using such designs would be able to account for individuals' changes in their work-life balance needs, their preferences for certain OWLI, and the impact of these dynamics on their job satisfaction levels as their family structure changes over time (Bennett et al., 2017). Moreover, and although the sample of this research included employees of different ages, the study did not examine, for instance, how generational characteristics influence employees' management of work-life interaction and their use of OWLI (Chung et al., 2018). Though the effects of age were found to be non-significant in the present research, a thorough consideration of these effects may be relevant in future studies, as employees from different generations may have distinctive expectations and needs regarding work-life interaction (Ehrhart et al., 2012). Thus, future research should continue to deepen the understanding of the role of OWLI in individuals' responses to work-life interaction by testing more complex models and by using larger samples and more sophisticated techniques (e.g., panel data analysis in the case of longitudinal studies). Finally, the present study relied exclusively on self-report data from a single survey, which may cause common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Although the results from Harman's one-factor test were satisfactory, future research may reduce common method bias by also measuring WLC and WLE through, for instance, significant others' perceptions of both phenomena (Breaugh & Frye, 2008).

Appendix

Escala de Iniciativas Organizacionales de Conciliación Trabajo-Vida

Indique con qué frecuencia utiliza los siguientes beneficios otorgados por su organización con el propósito de ayudarlo a conciliar el trabajo con la vida personal, utilizando una escala de 1 a 5, donde 1 significa "nunca la utilizo" y 5 "siempre la utilizo". En caso de no estar presente el beneficio en su organización por favor marcar "no disponible".

1. Horario de trabajo flexible, donde puedo, por ejemplo, gestionar el tiempo de trabajo según las necesidades que tenga en cada día variando los horarios de entrada y salida.

2. Acumulación de horas, donde puedo, por ejemplo, realizar horas extras durante la semana para tomar luego días libres.

3. Trabajo a tiempo parcial, donde la jornada laboral es menor a las 8 horas convencionales (ítem eliminado).

4. Licencia extendida, donde puedo, por ejemplo, ampliar los días de la licencia por maternidad/paternidad o los días de vacaciones por sobre los establecidos en la legislación laboral.

5. Trabajo desde la casa, donde puedo trabajar a distancia fuera de las oficinas cuando así lo requiero.

6. Apoyos económicos para el cuidado de niños dependientes, como, por ejemplo, para el pago de la cuota del colegio/ guardería/jardín o la reserva de plazas en establecimientos educativos.

7. Guardería de niños en el lugar de trabajo.

8. Apoyos económicos para el cuidado de adultos dependientes, por ejemplo, para el pago de la cuota del geriátrico.

9. Descuentos en distintos locales, como por ejemplo de venta de alimentos o restaurantes

10. Servicio de desayuno, almuerzo o merienda en las oficinas, o la provisión de servicios como el transporte (ítem eliminado).

11. Capacitaciones, como, por ejemplo, en gestión del tiempo, en idiomas, etc.

12. Beneficios médicos y de salud, como, por ejemplo, controles médicos anuales o la consulta médica con distintos profesionales disponibles en las oficinas de la organización.

13. Apoyos económicos para la realización de actividades físicas, como, por ejemplo, descuentos en gimnasios.

14. Asistencia a eventos y actividades recreativas de la organización, como, por ejemplo, after office o actividades al aire libre.

15. Asistencia a actividades de relajación organizadas por la organización, como clases de yoga o stretching.

Work-Life Balance Organizational Initiatives Scale1

1. Please indicate how often you use the following benefits provided by your organization to help you balance work and personal life, using a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 means "I never use it" and 5 means "I always use it." If the benefit is not available in your organization, please mark "not available."

2. Flexible work schedule, where I can, for example, manage my work hours according to daily needs by adjusting the start and end times.

3. Build-up time, where I can, for example, work overtime during the week to take days off later.

4. Part-time work, where the workday is shorter than the conventional 8 hours (item removed).

5. Extended leave, where I can, for example, extend maternity/paternity leave or vacation time beyond the period established by labor legislation.

6. Work from home, where I can work remotely outside the office when needed.

7. Financial support for dependent child care, such as paying school/daycare/kindergarten fees or reserving places in educational institutions.

8. Child daycare at the workplace.

9. Financial support for dependent adult care, such as paying nursing home fees.

10. Discounts at various stores, such as food or restaurants.

11. Breakfast, lunch, or snack service at the workplace, or provision of complimentary services such as transportation (item removed).

12. Training programs, such as time management, language proficiency, etc.

13. Medical and health benefits, such as annual check-ups or consultations with health professionals available at the workplace.

14. Financial support to promote physical activities, such as discounts for gym and fitness programs.

15. Organizational social events and recreational activities, such as happy hours or outdoor activities.

16. Stress relief activities for employees, such as yoga or stretching classes.