Gobies (Gobiformes: Gobiidae) constitute one of the largest families of marine fishes in the world. Currently, they comprise about 1866 species grouped in more than 280 genera and five subfamilies (Eschmeyer, Fricke, & van der Laan, 2017). Gobies are usually small fishes (less than 10cm) with elongated and robust bodies, and most species are characterized by having fully fused disc-shaped pelvic fins (Miller, Minckley, & Norris, 2009; Robertson & Van Tassell, 2015). Gobies are native to subtropical and tropical regions, inhabiting marine, brackish and freshwater ecosystems (Nelson, Grande, & Wilson, 2016).

The genus Gobionellus, comprising seven valid species, is distributed in the eastern Pacific from northern Peru to Baja California, Mexico, and in the western Atlantic from southern Brazil to North Carolina, USA, as well as the Gulf of Guinea in the eastern Atlantic (Pezold, 2004; Robertson & Van Tassell, 2015). To date, only Gobionellus microdon Gilbert, 1892 and Gobionellus oceanicus Pallas, 1770 have been recorded in Costa Rican waters. Gobionellus microdon, a species of marine origin that also may occur in freshwaters (Angulo, Garita-Alvarado, Bussing, & López, 2013) has been recorded in the Pacific slope, while G. oceanicus has been recorded only in marine ecosystems on the Atlantic slope (Robertson & Van Tassell, 2015). In this contribution we document the first occurrence of G. oceanicus in Costa Rican freshwaters.

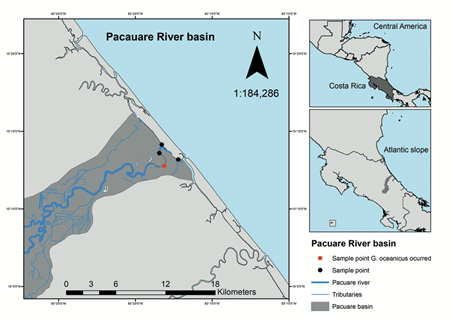

Fieldwork was carried out in February 2016 in four localities on the main channel of the Pacuare River in the province of Limón, Costa Rica on the Atlantic coast (Figure 1). Sampling gear included cast-nets and seine-nets. Water physicochemical variables were measured at each sampled locality with Hanna HI 9194 and Hanna HI 9813-5 multiparameters. Average width and the depth were measured at each sampled locality using a Nikon Prostaff 3 rangefinder and tape measure. The types of vegetation and substrate were characterized by direct observation. Specimens captured were identified in the field following Bussing (2002) and Robertson and Van Tassell (2015). Representative specimens were photographed, preserved and retained as vouchers. Remaining specimens were released after identification. Specimens were fixed in 10% formalin and preserved in 70% ethanol. Preserved specimens were deposited in the fish collection of the Museo de Zoología of the Universidad de Costa Rica (UCR). The identification of preserved specimens was corroborated in the laboratory; counts and measurements were carried out following Hubbs and Lagler (1970).

During fieldwork a single specimen of G. oceanicus (UCR 3211-001, see below) was collected. The specimen measured 139mm in standard length (SL, mm), 195mm in total length (TL, mm) and weighted 42g. The specimen was collected on the main channel of the Pacuare River (10°12'45" N; 83°18'6" W) at an elevation of 10masl and approximately 7km from the coast (Figure 1). The collection point was characterized by low water velocity with a depth of 3m and approximately 12m of river width. Substrate was composed mainly of rocks, silt and sand. Both ends of the river contained submerged vegetation, some emergent plants and typical species of riparian forest. The water temperature was 27°C, pH was 7, 8, dissolved oxygen was 3,0 (mg/L), conductivity was 233 (uS/cm) and salinity was 0,028ppt. Additional species collected at this locality were: Agonostomus monticola (Bancroft, 1834), Astyanax nicaraguensis Eigenmann & Ogle, 1907 (a primary freshwater fish species), Atherinella hubbsi (Bussing, 1979), Caranx latus Agassiz, 1831, the non-native Hypostomus aspidolepis (Günther, 1867; another primary freshwater fish species) and Mugil curema Valenciennes, 1836.

Identification of the specimen as G. oceanicus was based on the diagnosis of the species and descriptions made by Robertson and Van Tassell (2015). Diagnostic and distinctive characters include: body elongated and compressed, snout pointed and rounded; eyes large and located on the top of head, teeth conical in both jaws, dorsal-fin elements VI + I, 13, anal-fin elements I, 14; pectoral-fin elements 18; pelvic fins fused in a complete disc with I, 5 elements; caudal fin long and pointed; body completely scaled; nape scaled but rest of head scale less; scales rough with 67 small scales in lateral series; and lateral line absent. Additional meristic and some morphometric measurements of the specimen are provided in Table 1. Coloration in gobies is also important for identification. The general coloration pattern of the live specimen (Figure 2) included a light brown body colour, darker at the top of the head and along the bases of the dorsal fins, silvery ventrally, with several oblique thin bars directed downwards and backwards; buccal region yellow-green with blue dots (Figure 3); cheeks silver-green and a triangular silver patch on the gill cover and black spot on the trunk (more conspicuous in preservation); a dark spot at the base of the pectoral fin; and a dark spot at the base of the caudal fin.

Table 1: Morphometric data for Gobionellus oceanicus (UCR 3211-001) collected in the Pacuare River, Atlantic slope, Costa Rica

| Measurement | mm | %SL | %HL |

|---|---|---|---|

| TL | 195,0 | - | - |

| SL | 139,0 | - | - |

| Body depth | 23,5 | 16,9 | - |

| Body width | 19,2 | 13,8 | - |

| Head length (HL) | 28,0 | 20,2 | - |

| Head width | 18,0 | 13,0 | 64,4 |

| Snout length | 10,2 | 7,3 | 36,2 |

| Maxillary length | 10,2 | 7,4 | 36,5 |

| Eye diameter | 5,2 | 3,7 | 18,5 |

| Interorbital width | 3,7 | 2,7 | 13,3 |

| Pre-dorsal length | 39,2 | 28,2 | - |

| Pre-pectoral length | 29,4 | 21,2 | - |

| Pre-pelvic length | 28,9 | 20,8 | - |

| Pre-anal length | 73,1 | 52,6 | - |

| Dorsal-fin I height | 37,7 | 27,1 | - |

| Dorsal-fin II height | 18,3 | 13,1 | - |

| Pectoral-fin length | 25,5 | 18,3 | - |

| Pelvic-fin length | 23,6 | 17,0 | - |

| Anal-fin height | 13,9 | 10,0 | - |

| Caudal peduncle length | 13,4 | 9,7 | - |

| Caudal peduncle height | 12,7 | 9,2 | - |

| Caudal fin length | 56,0 | 40,3 | - |

Figure 2 Gobionellus oceanicus (UCR 3211-001) collected in the Pacuare River, Atlantic slope, Costa Rica; 139mm SL; photograph of fish immersed in water.

Figure 3 Detail of the head of G. oceanicus (UCR 3211-001), frontal view, showing the coloration pattern of the buccal region.

Generally, fish species of marine origin are usually dominant in inland coastal environments, constituting some of the most prominent components of freshwater fish faunas of many Central American countries (Álvarez, Matamoros, & Chicas, 2017; Greenfield & Thomerson, 1997; Matamoros, Schaefer, & Kreiser, 2009; McMahan et al., 2013). Costa Rica is no exception to this pattern given that 63,3% of species listed in the country are of marine origin that can be found in freshwater ecosystems (Angulo et al., 2013). In the most recent list of freshwater fish species in Costa Rica (Angulo et al., 2013), G. oceanicus was not listed; therefore, the present record increases to the number of native fish species in the freshwater ecosystems of Costa Rica to 253.

Reports of G. oceanicus in freshwater ecosystems are relatively scarce (Matamoros et al., 2009; Patzner, Van Tassell, Kovacic, & Kapoor, 2011), and the majority of records of this species are in brackish or marine ecosystems (Bolzan, Andrades, Spach, & Hostim-Silva, 2018; Díaz-Ruiz, Aguirre-León, Mendoza-Sánchez, & Lara-Domínguez, 2018; Pezold, 2004; Robertson & Van Tassell, 2015). Some authors suggest that G. oceanicus uses both marine and brackish ecosystems in different stages throughout its life cycle (de Andrade Tubino, Ribeiro, & Vianna, 2008; Gomes, Campos, & Bonecker, 2014), however frequency or abundance of G. oceanicus in freshwater systems is not very clear. To date, it is well known that some gobies use freshwater ecosystems for reproductive purposes (Keith & Lord, 2011); however, there is not enough evidence about this phenomenon in G. oceanicus, although it is possible that this species colonizes freshwater ecosystems in search of food or shelter.

At present there has been little information published about the biology of G. oceanicus. Information exists regarding some aspects of preferred habitat structure in areas where G. oceanicus occurs (Pezold, 2004; Robertson & Van Tassell, 2015). There are additionally some studies describing the behaviour of this species at early stages of development (Gomes et al., 2014; Wyanski & Targett, 2000) and basic aspects of diet (de Medeiros, de Amorim Xavier, & de Lucena Rosa, 2017). The present record of G. oceanicus in Costa Rican freshwaters reaffirms the capacity of this species to inhabit environments with low or no salinity. Additional studies are necessary to better understand the biological explanations for the occurrence of this species in freshwater ecosystems. We hope that this information will be the starting point for future research on G. oceanicus, as well other peripheral species using freshwater ecosystems, in Costa Rica and throughout Central America.

uBio

uBio