Galls are neoformed plant organs (Shorthouse, Wool, & Raman, 2005) developed from host-plant tissues as a result of cell multiplication and re-differentiation (sensuLev-Yadun, 2003) after induction by gall-inducing organisms (Raman, Cruz, Muniappan, & Reddy, 2007; Oliveira et al., 2016). These neoformed plant organs possesses cells with new fates and rapid cell cycles (Carneiro & Isaias, 2015), which can provide nutrition and protection against environment stressors and natural enemies for the gall-inducing organism (Price, Fernandes, & Warring, 1987; Stone & Schönrogge, 2003; Formiga, Gonçalves, Soares, & Isaias, 2009; Formiga, Soares, & Isaias, 2011). Insects generally induce well-defined galls, which are considered the most specialized because they encompass a great diversity of morphotypes (Roskam, 1992; Raman, Schaefer, & Withers, 2005; Isaias, Carneiro, Oliveira, & Santos, 2013). In the Neotropics, galls are induced mostly by species of the family Cecidomyiidae (Gagné, 1994; Fernandes & Santos, 2014). The species Eugeniamyia disparMaia, Mendonça, & Romanowski 1996 (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae), for example, induces pale green galls on the adaxial surface of young leaves of Eugenia uniflora L. (Myrtaceae). In this system new galls are being induced, developing and going through senescence throughout the year (Mendonça & Romanowski, 2002).

The feeding of gall-inducing insects induces stress in host-plant cells, which can be detected by the presence of hydrogen peroxide, a reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Isaias, Coelho, & Carneiro, 2011; Oliveira, Isaias, Moreira, Magalhães, & Lemos-Filho, 2011b; Isaias, Oliveira, Moreira, Soares, & Carneiro, 2015; Oliveira et al., 2016). These molecules were initially recognized as unhealthy for plant cells since they are able to cause damage to a variety of cellular structures (Petrov & Van Breusegem, 2012). However, they can also play an important role in molecular signaling during plant organ development (Del Río & Puppo, 2009), and consequently in gall morphogenesis and physiology (Isaias et al., 2015; Oliveira et al., 2016). Among the changes caused by the feeding activity of gall-inducing insects is the accumulation of primary metabolites (Bronner, 1992). Cecidomyiid galls, for example, possess a histochemical gradient associated with a large accumulation of certain primary metabolites near the larval chamber, thereby forming nutritive tissue, while others (such as starch) accumulate more distant from the larval chamber and are known as reserve tissues (Bronner, 1992; Ferreira, Álvarez, Avritzer, & Isaias, 2017). In addition to nutritive tissue formation, structural and physiological alterations, such as decreases in the amount of chlorophyllous tissues, pigment content, gas exchange, and photosynthetic rates, have been detected in gall tissues (Florentine, Raman, & Dhileepan, 2005; Oliveira et al., 2011b; Oliveira, Moreira, Isaias, Martini, & Rezende, 2017). Nonetheless, green galls should maintain their photosynthetic activity in spite of the oxidative stress and structural changes caused by the gall-inducing organism. This maintenance of photosynthetic activity would have interesting implications for the oxygen and carbon dioxide cycle of galls by reducing hypoxia and hypercarbia (Castro, Oliveira, Moreira, Lemos-Filho, & Isaias, 2012; Haiden, Hoffmann, & Cramer, 2012; Oliveira et al., 2017).

Herein, we assess the structural, histochemical and physiological profiles of galls induced by E. dispar (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) on leaves of E. uniflora (Myrtaceae). We address the following questions: (i) How does this gall-inducing insect changes the structural and histochemical profiles of the host-plant organ? (ii) Despite structural changes, can gall tissues maintain photosynthetic activity?

Materials and methods

Study area and plant material: Nongalled leaves and galls of E. dispar - E. uniflora were sampled from vegetation on the campus of the Universidade Federal de Uberlândia (18°53”7.8’ S - 48°15”36’ W, Uberlândia), Minas Gerais, Brazil. The sampled plants (n = 5) were pruned to provoke periodical new leaf flushes, and thus maintain gall populations throughout the year. The samples were collected between January and April 2015.

Anatomical and histochemical analyses: Anatomical and histochemical analyses were performed with non-galled leaves (n = 10) and mature galls (n = 10), both from the third node. Galls were considered as mature from the formation of a distinguishable larval chamber until the exit of the insect. For structural analysis, samples were fixed in FAA (formalin, acetic acid, 50 % ethanol, 1:1:18 v/v/v) for 48 hours (Johansen, 1940), dehydrated in an ethanol series, embedded in 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (Historesin, Leica Instruments, Germany), and sectioned using a rotary microtome (YD-315 model, China) at a thickness of 4-5 μm. The sections were stained with 1 % toluidine blue at pH 4.0 (O’Brien, Feder, & McCully, 1964) and mounted with Entellan®.

Histochemical analyses were performed on samples embedded in polyethylenoglycol (PEG 6000) (Ferreira, Teixeira, & Isaias, 2014) and sectioned in a rotary microtome at a thickness of 25 µm, or on free-hand sections (using razor blades) obtained from recently collected non-galled and galled samples. Lugol’s test was used for detection of starch (Johansen, 1940); bromophenol blue for total protein (Baker, 1958); Sudan Red B for total lipids (Brundett, Kendrick, & Peterson, 1991); Fehling’s reagent for reducing sugars (Sass, 1951); and the DAB test “0.5 % 3,3’diaminobenzidine” (DAB Sigma®) for hydrogen peroxide (Rossetti & Bonnatti, 2001). Control tests were conducted as recommended for each of the histochemical tests, while comparisons were also made using non-stained sections.

All samples were analyzed and photographed with a Leica® DM500 photomicroscope coupled to a Leica® ICC50HD camera. The area occupied by the chlorophyllous tissues was measured using the software Image Pro-Plus (version 4.1 for Windows®, Media Cybernetics).

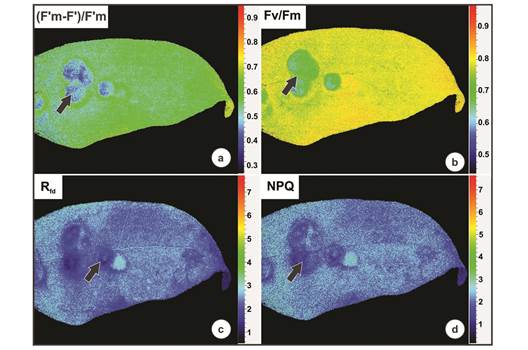

Photosynthetic performance and content of photosynthetic pigments: Photosynthetic performance of non-galled leaves (n = 6) and mature galls (n = 6), both from the third node, was evaluated by chlorophyll a fluorescence using a Handy FluorCam-PSI (Photon Systems Instruments). The samples were covered for 30 minutes (dark adaptation) prior to evaluation in the laboratory, and the photosynthetic parameters reported according Genty, Briantais and Baker (1989) and Oxborough (2004). The following photosynthetic parameters were evaluated using Fluorcam7 software (protocol Quenching): F0 = minimal fluorescence in dark-adapted state; Fm = maximum fluorescence in dark-adapted state; Fv/Fm = maximum quantum yield; NPQ = non-photochemical quenching during light adaptation; Rfd = fluorescence decline ratio in steady-state (an empirical parameter used to assess plant vitality); and (F’m-F’)/F’m = PSII operating efficiency (where F’m is the fluorescence signal when all PSII centers are closed in the light-adapted state, and F’ is the measurement of the light-adapted fluorescence signal).

Photosynthetic pigment content was determined for 0.8-cm2 disks taken from non-galled leaves (n = 30, six leaves per plant, five plants) and mature galls (n = 30). The samples were weighed and immersed in 5 ml of 80 % acetone for 48 hours, macerated and centrifuged at 3 000 rpm[G] for three minutes. The extracts were analyzed in a UV- VIS spectrophotometer (SP-220 model, Biospectro, Brazil) at wavelengths of 470, 646 and 663 nm. Chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoid levels were measured following Lichtenthaler and Wellburn (1983).

Statistical analyses: Physiological analyses of galls and non-galled leaves were compared using means and standard deviations calculated using JMP® 4 software (SAS Institute).

Results

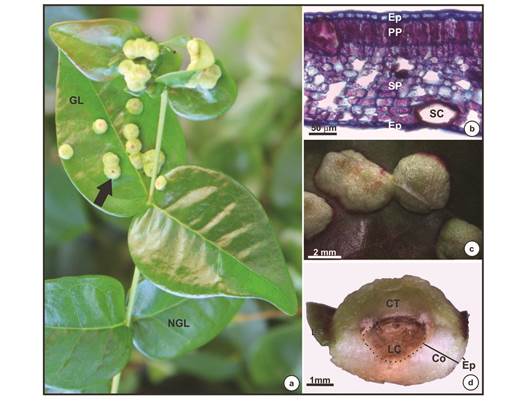

Morphological and anatomical features: The leaves of E. uniflora are simple, glabrous, oblong-lanceolate with entire margins and opposite phyllotaxy (Fig. 1a). In cross section, they are hypostomatic, with a uniseriate epidermis and mesophyll comprising two layers of palisade parenchyma and about nine layers of spongy parenchyma. Secretory canals occur in the mesophyll (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1 Morphological and anatomical characteristics of non-galled leaves and galls induced by Eugeniamyia dispar on Eugenia uniflora leaves. a- Branch with non-galled leaves and galls. Arrow indicates a gall; b- anatomical detail of nongalled leaf in cross section; c- macroscopic view of galls; d- cross section of gall. Abbreviation: GL- galled leaf; NGL- nongalled leaf; Ep- epidermis; PP- palisade parenchyma; SP- spongy parenchyma; SC- secretory cavity; CT- chlorophyllous tissue; LC- larval chamber; Co- cortex; Le- leaf.

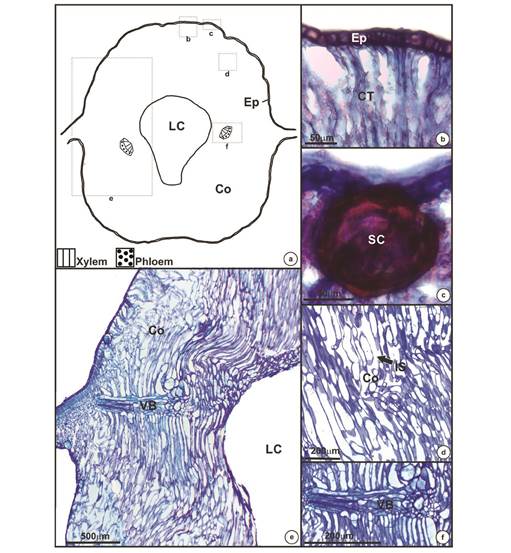

The E. dispar - E. uniflora galls possess a globular shape and occur singly or in clusters (Fig. 1a, Fig. 1b and Fig. 1c). They are intralaminar, projecting on both leaf surfaces, and contain a single larval chamber occupied by one gall-inducing insect larva when the gall occurs singly (Fig. 1d). The galls possess chlorophyllous tissue particularly in the adaxial surface (Fig. 1d). Structural analysis of the galls revealed an uniseriate epidermis (Fig. 2a, Fig. 2b y Fig. 2c) with secretory canals below (Fig. 2c). The cells of the cortex are anticlinally elongated (Fig. 2d, Fig. 2e), with large intercellular spaces mainly among the outer layers (Fig. 2d). Around the larval chamber the tissue is compact and without any intercellular spaces (Fig. 2e). Vascular bundles are distributed around the larval chamber and ramify laterally (Fig. 2a, Fig. 2e, Fig. 2f). At maturity, most of the nutritive tissue of the galls is partially or totally absent.

Fig. 2 Anatomic structure of mature galls of Eugenia uniflora induced by Eugeniamyia dispar. a- Schematic representing gall shape and regions where the anatomy is highlighted; b- uniseriate epidermis; c- secretory cavity; d- outer layers of the cortex; e- one side of the gall, from the epidermis to the larval chamber; f- vascular bundle. Abbreviation: Ep- epidermis; Co- cortex; LC- larval chamber; CT- chlorophyllous tissue; SC- secretory cavity; IS- intercellular space; VB- vascular bundle.

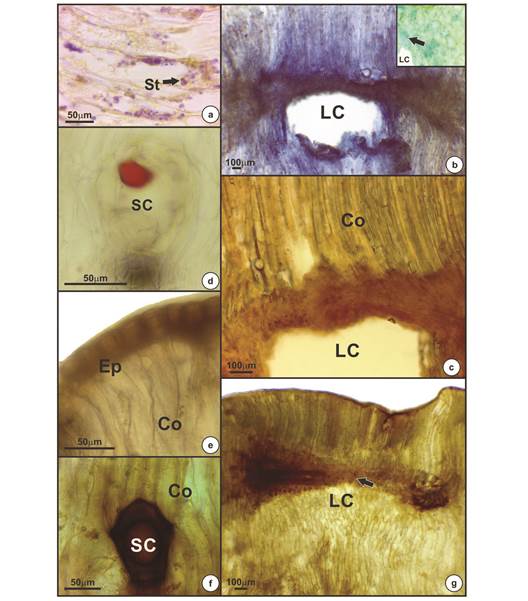

Histochemical profile: Starch grains (Fig. 3a), proteins (Fig. 3b) and reducing sugars (Fig. 3c) were detected in the galls but only around the larval chamber, while lipid substances were detected in the secretory canals (Fig. 3d). The DAB test for oxidative stress revealed the presence of hydrogen peroxide (a ROS molecule) especially in the epidermis (Fig. 3e), secretory canals (Fig. 3f) and vascular bundles around the larval chamber (Fig. 3g).

Fig. 3 Positive histochemical results for mature galls of Eugenia uniflora induced by Eugeniamyia dispar. a- Starch occurring near the larval chamber; b- proteins around the larval chamber; c- reducing sugar near the larval chamber; d- lipid compound detected in secretory cavity; e, f, g- oxidative stress occurs predominantly in the epidermis (e), secretory cavities (f) and in the vascular bundles near the larval chamber (g). Abbreviation: St- starch; LC- larval chamber; Co- cortex; SC- secretory cavity; Ep- epidermis.

Pigment content and chlorophyll a fluorescence: Total chlorophyll and carotenoids were higher in non-galled leaves (Average AV = 2.7 ± Standard Error SE = 0.2 and AV = 0.3 ± SE = 0.02 mg g-2 of fresh mass, respectively) than in galls (AV = 1.3 ± SE = 0.1 and AV = 0.2 ± SE = 0.03 mg g-2 of fresh mass, respectively); however, the ratio of chlorophyll a/b was similar (AV = 1.7 ± SE = 0.2 and AV = 2.1 ± SE = 0.1 for non-galled leaves and galls, respectively). The chlorophyll/carotenoids ratio was higher in non-galled than galled tissues (AV = 9.6 ± SE = 1.2 and AV = 6.3 ± SE = 0.4, respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1 Means and standard errors of photosynthetic pigments (mg g-2 of fresh mass) in non-galled leaves and galls induced by Eugeniamyia dispar on Eugenia uniflora leaves

| - | - | Parameters | - | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples | Total chlorophyll | Carotenoids | Chlorophyll a/b | Chlorophyll/carotenoids | |

| Non-galled leaves | 2.72 ± 0.19a | 0.31 ± 0.024a | 1.73 ± 0.15a | 9.55 ± 1.16a | |

| Galls | 1.28 ± 0.12b | 0.22 ± 0.029b | 2.13 ± 0.14a | 6.27 ± 0.38b | |

*Means followed by different letters differ statistically within the same parameter (P ˂ 0.05).

Galls exhibited different values for the chlorophyll fluorescence parameters when compared with non-galled leaves (Table 2). The galled tissues had a higher minimal fluorescence of PSII in the dark-adapted state (F0) than the non-galled tissues (AV = 389.5 ± SE = 20.9 and AV = 313.9 ± SE = 12.7, respectively). The maximum fluorescence of PSII in the dark-adapted state (Fm), the PSII operating efficiency [(F’m-F’) / F’m], the maximum quantum yield (Fv/Fm), and the fluorescence decline ratio in steady-state (Rfd) were all higher in non-galled leaves than galled tissues (Fig. 4a, Fig 4b y Fig. 4c; Table 2). Energy dissipation through non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) did not differ between non-galled and galled tissues (Fig. 4d; Table 2).

Table 2 Means and standard errors of chlorophyll a fluorescence performed on non-galled leaves and galls induced by Eugeniamyia dispar on Eugenia uniflora leaves

| - | - | - | Parameters | - | - | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples | F0 | Fm | (F’ m -F’)/F’ m | Fv/Fm | Rfd | NPQ | ||

| Non-galled leaves | 313.9 ± 12.7b | 1 480.84 ± 55.1a | 0.77 ± 0.06a | 0.79 ± 0.14a | 2.41 ± 0.19a | 1.98 ± 0.21a | ||

| Galls | 389.53 ± 20.9a | 1 259.45 ± 61.8b | 0.60 ± 0.08b | 0.69 ± 0.08b | 1.55 ± 0.05b | 1.92 ± 0.19a | ||

*Means followed by different letters differ statistically within the same parameter (P ˂ 0.05).

F0: minimal fluorescence in dark-adapted state; Fm: maximum fluorescence in dark-adapted state; (F’m-F’)/F’m: PSII operating efficiency; Fv/Fm: maximum quantum yield; Rfd: fluorescence decline ratio in steady-state; NPQ: nonphotochemical quenching during light adaptation.

Fig. 4 Chlorophyll a fluorescence performed on galls induced by Eugeniamyia dispar on Eugenia uniflora leaves. a- PSII operating efficiency ((F’m-F’)/F’m); b- the maximum quantum yield (Fv/Fm); c- fluorescence decline ratio in steady-state (Rfd); d- energy dissipation through non-photochemical quenching (NPQ).

Discussion

Eugeniamyia dispar manipulates the tissues of E. uniflora to develop leaf galls. Proteins and reducing sugars were detected mainly in the cells surrounding the larval chamber, which is a typical induced nutritional gradient for galls (Bronner, 1992). Although uncommon, starch was also detected in cells around the larval chamber. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) were detected around the larval chamber in association with primary metabolites, especially proteins, which is indicative of biotic stress (Schönrogge, Harper, & Lichtenstein, 2000). Stress was also detected in gall tissues by chlorophyll a fluorescence, which demonstrates that galls retain a low-level photosynthetic capacity, as observed in other Neotropical gall systems (Castro Oliveira, Moreira, Lemos-Filho, & Isaias, 2012; Oliveira et al., 2017). Associated with low photosynthetic activity, many intercellular spaces may facilitate gas diffusion, as has been previously proposed for other gall systems (Pincebourde & Casas, 2016).

Cell hypertrophy is the most important and convergent morphological feature induced by gall-inducing insects in their host-plants (Mani, 1964; Shorthouse & Rohfritsch, 1992; Isaias, Oliveira, Carneiro, & Kraus, 2014; Magalhães, Oliveira, Suzuki, & Isaias, 2014; Oliveira et al., 2016; Carneiro, Isaias, Moreira, & Oliveira, 2017). This process frequently leads to the formation of compact tissues, as observed in the horn-shaped galls and midrib galls induced by cecidomyiids on leaves of Copaifera langsdorffii Desf. (Fabaceae) (Oliveira & Isaias, 2010a; Castro et al., 2012), in the intralaminar galls induced by sucking insects on Aspidosperma australe Müll.Arg (Apocynaceae) (Oliveira & Isaias, 2010b), and in several other systems (Mani, 1964). The development of compact tissue is associated with a decrease of intercellular spaces and, consequently, a reduction of water loss (Heldt & Piechulla, 2010; Castro et al., 2012) and a deceleration of gas diffusion in gall tissues (Pincebourde & Casas, 2016). Despite the formation of compact tissues in different gall systems, the galls induced by E. dispar on leaves of E. uniflora have large intercellular spaces in the outer layers. These intercellular spaces may help to maintain gas diffusion and, consequently, avoid hypoxia and hypercarbia in gall tissues (Pincebourde & Casas, 2016; Oliveira et al., 2017).

Galls induced by cecidomyiids commonly develop nutritive tissues around the larval chamber (Bronner, 1992; Ferreira et al., 2017). These nutritive tissues usually store proteins and reducing sugars that may be used as food by the gall-inducing insect larva (Bronner, 1992; Oliveira, Carneiro, Magalhaes, & Isaias, 2011a; Ferreira & Isaias, 2013, 2014; Vecchi, Menezes, Oliveira, Ferreira, & Isaias, 2013; Ferreira et al., 2017). In galls induced by species of Cecidomyiidae on leaves of Aspidosperma spruceanum Benth ex Müll.

Arg. (Apocynaceae) and Piper arboreum Aubl. (Piperaceae), such proteins are associated with the high metabolism and oxidative stress caused by the gall-inducing insect (Schönrogge et al., 2000; Oliveira et al., 2011b; Bragança, Oliveira, & Isaias, 2017), which also occurs with galls induced by E. dispar on E. uniflora. The starch and reducing sugars detected in the cells around the larval chamber of galls induced by E. dispar may function as energetic resources for both gall-inducing insect nutrition and maintenance of the cell machinery of the gall, as proposed for other systems (Oliveira et al., 2011a; Ferreira & Isaias, 2013; Isaias et al., 2014; Oliveira et al., 2016; Bragança et al., 2017; Ferreira et al., 2017). Although uncommon in the nutritive tissue, starch grains have been detected in galls induced by cecidomyiids (Oliveira et al., 2011a). Lipids have been reported from galls produced by species of Cynipidae and Lepidoptera (Bronner, 1992; Vechi et al., 2013), and have also been detected in galls induced by species of Cecidomyiidae on A. spruceanum (Oliveira, Magalhães, Carneiro, Alvim, & Isaias 2010), C. langsdorffii (Oliveira et al., 2011a), Marcetia taxifolia (A.St.-Hil.) DC. (Ferreira & Isaias, 2014) and Lantana camara L. (Moura, Soares, & Isaias, 2008). Although lipids are commonly produced by the intrinsic metabolism of leaves of E. uniflora (Victoria et al., 2012), these substances were not detected in the compact cortex of their galls and occur only in the secretory canals. These findings clearly indicate how insects can manipulate, and even block, some of the substances produced by the metabolism of the host-plant.

Even though the galls induced by E. dispar on leaves of E. uniflora retain chlorophyllous tissue in the outer layers of the gall cortex, the photosynthetic activity of this new organ is reduced. This reduction is likely due to an increase in oxidative stress induced by the gall-inducing insect, and a reduction in pigment content (Oliveira et al., 2011b; Isaias et al., 2015). The reduction in pigment content may be a consequence of cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia, which increases gall volume (Oliveira et al., 2017). The reduced area of chlorophyllous tissue in galls, compared to non-galled leaves, found in the present study may contribute to the decreased photosynthetic rate, as reported for other gall systems (Carneiro Castro, & Isaias, 2014). A reduction in photosynthetic pigment content has also been reported for horn-shaped galls induced by species of Cecidomyiidae on leaflets of C. langsdorffii (Castro et al., 2012), and intralaminar galls on leaves of A. spruceanum (Oliveira et al., 2011b). This reduction also negatively affects the photosynthetic rates of the gall tissues. Carotenoids and NPQ are responsible for energy dissipation during the xanthophyll cycle and, consequently, prevent damage to the photosynthetic apparatus during stress (Demmig-Adams & Adams, 1996). Contrary to expectations, there was a decrease in carotenoid content in gall tissues compared to non-galled leaves of E. uniflora, an indication that the gall tissue may invest in different mechanisms for stress dissipation and maintenance of tissue homeostasis (Isaias et al., 2015; Oliveira et al., 2017); we also detected a decrease of NPQ levels in galls induced by E. dispar on leaves of E. uniflora.

Studies of photosynthetic performance have shown that gall development may not alter photosynthetic rates in relation to nongalled organs (Fernandes et al., 2010; Oliveira et al., 2010, 2011b) or may even increase it (Bagatto, Paquette, & Shorthouse, 1996). The maximum quantum efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm) and PSII operating efficiency [(F’m-F’)/F’m] are important parameters for evaluating photosynthetic performance (Maxwell & Johnson, 2000; Oxborough, 2004), and which decreased in gall tissues of E. uniflora. These results are similar to those found for galls induced by Bystracoccus mataybae on leaflets of Matayba guianensis (Oliveira et al., 2017), galls induced by aphids (Larson, 1998), and galls of Epiblema strenuana induced on Parthenium hysterophorus (Florentine et al., 2005).

A useful parameter for detecting biotic stress on the photosynthetic apparatus is the initial fluorescence level (F0), which may increase when the reaction center of PSII is damaged, or if the transfer of excitation energy from the antenna complex is impaired (Bolhar-Nordenkampf et al., 1989). The high value of F0 in the galls of E. uniflora supports the idea of damage to the photosynthetic apparatus therein, probably due to oxidative stress induced by the gall-inducing insect. In addition, an important symptom of stress is a decrease in Rfd (fluorescence decline ratio in steady-state), an empirical parameter used to assess plant vitality and a diagnostic parameter for plant stress (Lichtenthaler & Miehé, 1997). The galls of E. uniflora experienced a decrease of Rfd compared to non-galled leaves. Thus, Rfd can be used as an efficient parameter for measuring the biotic stress induced by gallinducing insects (Oliveira et al., 2017).

The galls of E. uniflora induced by E. dispar exhibited specific anatomical features, such as cell hypertrophy, hyperplasia, large intercellular spaces in the outer cell layers of the gall cortex, and nutritive tissue around the larval chamber. In this tissue, reserve compounds, especially proteins, were detected. The structural changes provoked by gall-induction deviate from the normal ontogenetical functions of the host leaves, although one of the primary functions of the leaves, photosynthesis, remains at low levels in this new organ, the gall.

uBio

uBio