1. Introduction

Contemporary organisational studies increasingly recognize the imperative of embracing diverse and transformative methodologies, particularly within the evolving landscape of feminist organisational theory and change (Wajcman, 1991). This paper delineates a comprehensive exploration of a Feminist Action Research project conducted within the realm of organisational change processes, aiming to shed light on its distinctive contributions vis-à-vis more conventional approaches. Situating itself at the nexus of feminist epistemologies, participatory methodologies, and organisational change theories, this research project unfolds as an endeavour to bridge the gap between the theoretical underpinnings of feminist organisations and the practical implementation of transformative processes, in line with Acker (1990) .

This study explores the use of Feminist Action Research as a methodology in the context of Solidarity Economy in the Valencian Community. The research focuses on an organisation operating under the principles of the solidarity economy, aiming to contribute to the strengthening of its practices and the achievement of its social objectives. Through this approach, the study seeks not only to analyse the internal dynamics of the organisation but also to provide tools and strategies that can be used to enhance its impact on the community.

The study originates from a collaboration between academia and a Solidarity Economy organisation, initiated in 2019 to begin an organisational reflection based on the principles of Feminist Economics. This organisational reflection was conducted through the facilitation of the researcher over the course of a year, utilizing various workshops complemented by interviews. The outcome of these activities was an Action Plan through which the organisation, XEAS País Valencià, established strategic lines of work aimed at developing organisational transformation. This transformation seeks to create a more habitable, decommodified, and depatriarchalized organisation.

The main objective of this work is to expose the experiences derived from a research initiative conducted within the framework of Feminist Action Research. It seeks to unveil the distinctive contributions of this methodology when juxtaposed with more hermeneutic or interpretative approaches. Additionally, the study aims to investigate and disseminate the methodology of organisational change processes, analysing its contributions to the theories of ‘women in management’ and its relevance to the existing literature and methodologies of organisational change.

The importance of this work lies in the need to understand and support solidarity economy organisations, which represent an alternative to the traditional economic model. These organisations aim to promote values of equity, solidarity, and sustainability, and their strengthening is crucial for building a fairer society. In this context, Feminist Action Research emerges as a powerful tool, as it not only allows for a deep understanding of social dynamics but also facilitates the active participation of those involved in the research process.

This study is part of a doctoral thesis that aimed to contribute to ongoing social processes. The choice and development of the Feminist Action Research methodology were not random but stem from a clear political stance of the researchers. From this perspective, research is understood as another tool for social change, where the knowledge generated not only describes reality but seeks to transform it. The commitment to this methodology reflects the dedication to participatory, inclusive, and action-oriented research.

The main contribution of this article lies in its demonstration of how Feminist Action Research can be effectively applied to facilitate organisational transformation within a solidarity economy context. By detailing the process and outcomes of the collaboration between academia and the XEAS País Valencià organisation, the study provides valuable insights and practical strategies for creating more equitable, sustainable, and inclusive organisational structures. This contribution underscores the potential of feminist methodologies to drive meaningful social change and enhance the effectiveness of solidarity economy initiatives.

The initial section of this introduction highlights the contextual imperatives prompting a departure from conventional management paradigms. In recognition of the escalating significance of qualitative research methods (Creswell, 2017) in struggling with the complexities of distinct organisational and social landscapes, we assert their growing indispensability. Thus, this paper positions itself within a broader intellectual framework, advocating for qualitative research methods, as essential instruments for navigating the proposals of feminist organisational change (Powell, 1999). Section 2 introduces the main theories of feminist organisations, while section 3 reviews the primary contributions made through the lens of feminist action research methodologies. Section 4 presents the methodological underpinnings of the article and outlines the steps taken in the study. Section 5 reports the results. The discussion of results is presented in section 6. Lastly, section 7 concludes with several lessons learned that can be applied in similar settings.

2. Traditional vs critical approaches on gender in organisations: a literature review

Approaches to ‘gender in organisations’ are diverse and stem from various fields and ideological frameworks (Arias-Cascante & León-Jiménez, 2013). The term ‘organisation’ is broad and can refer to businesses, institutions, social organisations, organised civil society, associations, and so forth (Calás et al., 2014). First, we will review the literature in organisational studies, specifically Feminist Theories of Organisation (FTO, hereafter). This body of literature primarily focuses its analysis on business organisations, especially those in the global North.

The literature review of Feminist Theories of Organisation has been instrumental in contextualizing the evolution and development of feminist theories within the realm of organisational studies. Scholars such as Marta B. Calás, Linda Smircich, and Elvina Holvino have played a central role in this effort, providing a synthesis of the trajectories and currents in literature through articles like ‘Theorizing Gender-and-Organisation: Changing times…changing theories’ (2014) and ‘Feminist Theories of Organisation’ (2016).

Feminist Theories of Organisation are diverse, stemming from different paradigms and approaches (Calás et al., 2014), much like feminisms (hence the plural). Nevertheless, various distinguishable currents, although not explicitly classified as such, emerge from the studies of FTO.

2.1 Gender in organisations

The literature on ‘gender in organisations’ is more naturalistic in approach and focuses on individuality, understanding the sex-gender system but placing the emphasis on individuality (Calás et al., 2014). On one hand, there are works that have focused on observing gender-based differences within the organisation, conceived as a gender-neutral space (Acker, 1990; Calás & Smircich, 2016). Understanding organisations as gender-neutral is a perspective that contends that organisations, in themselves, do not reproduce inequalities in their forms and dynamics, but rather, these inequalities arise among individuals based on their gender. This approach of viewing the organisation as gender-neutral overlooks mechanisms that reproduce patriarchal social structures, acting not only as barriers to equal job opportunities but also generating spaces of inequality, discrimination, and violence as seen at the societal level.

These studies have focused on highlighting glass ceilings, sticky floors, and differences in management practices between men and women, shedding light on the discriminations and barriers to access and career advancement for women (Calás & Smircich, 2016). Many of these studies align with the premises and practices of liberal feminisms, which pursue equality under the promotion of individual freedoms as a personal empowerment exercise. They focus on conducting gender-disaggregated analyses of various organisational spaces and practices (Calás & Smircich, 2016). They have had a significant influence on U.S. management studies and are relatively scarce in schools and universities. Part of this current includes studies influenced by psychoanalytic theories from the 1970s that aimed to explore the ‘differences’ and ‘advantages’ of women’s leadership and management, with the mission of extracting greater effectiveness, competitiveness, and productivity by incorporating women into work teams (Calás & Smircich, 2016). Many authors refer to these studies as ‘gender in organisations’ to emphasize their approach to gender as a variable or characteristic of organisational reality. In general, in most journals, books, and publications, these studies are referred to and classified as ‘women in management.’

As stated by Marta Calás and Linda Smircich, these arguments completely depoliticized feminist claims but allowed these studies to find a place in academia and the popular press (2016, p. 3). Despite being the pioneering studies of Feminist Theories of Organisation, this current continues to have a significant impact on management studies and has been introduced into a large number of scientific journals in the field. However, as Paloma Càceres emphasizes, ‘the evidence generated in this line was not and is not enough’ (2019, p.11) . Therefore, they propose to go beyond and question the causes and structures that generate these inequalities in organisations, aiming to articulate strategies to subvert them.

2.2 Gendering organisations

On the other hand, research and theories have been developed that broaden this perspective and align with socialist feminisms and critical theory (Acker, 1990). They explore the ways in which organisations, through strategies, their own structure, spaces, communication, and activities, reflect and reproduce patriarchal dynamics that are not ‘gender-neutral’ but perpetuate roles, stereotypes, and ultimately generate spaces of discrimination and inequality.

Among the pioneers in this line of studies was the American sociologist Joan Acker (1990) , who introduced the term ‘gendered organisations’ into organisational studies literature, meaning organisations that reproduce gender systems and norms. Thus, organisations are understood as ‘regimes of inequality that interconnect organisational processes and practices that produce and maintain class, racialized, and gender relationships’ (Calás & Smircich, 2016, p. 4). These studies, which had more impact in the sociology school than in North American business schools (Calás & Smircich, 2016), represented a clear critique of ‘women in management’ studies.

Joan Acker defined these inequality regimes as those ‘interrelated practices, processes, actions, and meanings that produce and maintain inequalities of class, gender, and race within organisations’ (Acker, 2006, p.443). These regimes are diverse and operate in different ways. They are dynamic and changing, tending to reproduce inequalities from the social, historical, political, and cultural context in which each organisation is situated (Acker, 2006). The author has delved into various works on the characteristics and ways in which inequality operates.

According to Joan Acker, these processes were simultaneously traversed by the presence of class-based social relations, as she emphasized in Acker (1988) and later developed in a significant portion of her literature (Acker, 2006, 2011). Thus, stating that an organisation is ‘gendered’ means that ‘advantage and disadvantage, exploitation and control, action and emotion, meaning and identity are shaped through and in terms of a distinction between masculine and feminine’ (1990, p.146). Therefore, gender is conceived as an integral part of processes that are not gender-neutral and cannot be understood without appropriate gender analysis (Connell 1987; West & Zimmerman 1987, cited in Acker, 1990).

Acker (1990) highlights that these gendered processes, within which organisations are situated, encompass not only the division of labour, permissible and expected attitudes, and workplace spaces but also all the images and symbols that reproduce these differences and inequalities. Furthermore, she points out that these processes include all patterns that endorse dominance and submission in relationships between individuals in the organisation. Additionally, these processes generate the production of individual identities that internalize patterns and reproduce gendering mechanisms (Reskin & Roos 1987).

Distinguishing itself from the literature on ‘women in management’ and ‘gender and organisation,’ authors adopting a feminist sociology perspective with a constructionist analysis of social processes referred to the concept of ‘gendering organisations.’ ‘Gendering’ encompasses practices, images, ideologies, and power distribution contributing to the production and reproduction of social and organisational processes (Calás et al., 2014). Instead of viewing gender as an attribute or variable among individuals within organisations, these authors considered ‘gendering’ as an outcome of organisational processes. Furthermore, rather than placing individuals at the centre of the issue and assuming binary notions, they conceptualize gender as a social institution (Calás et al., 2014).

Natalia Navarro (2007) argues that gendering processes refer to ‘how the feminine and masculine are articulated and endowed with meaning, and how everything comes to be considered as belonging to one or the other, so that the associated value, opportunities, and limitations are different and hierarchized’ (p.22). Thus, she emphasizes the importance of identifying patterns of differentiation between the feminine and masculine as configured in organisational hierarchies (through practices, relationships, attitudes, etc.). From these premises, organisations are understood as a ‘gendered and gendering product simultaneously’ (Navarro, 2017, p. 10).

In conclusion, there is a significant contrast between different currents, as seen in other knowledge areas, as well as a difference in their contribution to reducing inequalities. Some of these positions have ended up repeating and documenting things we already know under the mantra of ‘objectivity’ (Calás et al., 2014). On the other hand, feminist research in the organisational realm has raised questions about whether literature and academia can do more than merely documenting these facts to bring about structural and daily changes in the realities of organisations.

3. Feminist organisational change processes. An Action Research methodology

The historical journey and review of the literature on Feminist Theories of Organisation help us place feminist organisational change within a certain genealogy, positioning the reflections and demands of feminist activists in these knowledge areas as those that, in a way, drove the need to undertake these processes. It is a fact that the rapid economic, social, and environmental transformations occurring in our society and planet are influencing new forms of business organisation, labour relations, and the risks faced by the working population (Askunze-Elizaga, 2023).

This research aligns theoretically with the approach to organisational change that assumes organisations are ‘gendered’ and ‘gendering.’ This perspective recognizes organisations as spaces where power relations are reproduced and produced, intersected by many more realities. It understands gender from an intersectional perspective, much broader than solely focusing on the binary reality of what happens to men and women in the organisation (Navarro, 2011). In fact, significantly transformative processes of feminist organisational change are those that not only address the reality of what ‘happens’ or is visible but also delve into the causes of why this happens and, in some way, organise to combat them. In other words, the goal is not just to have a board of directors composed of women as a norm after the organisational change process but to explore the barriers that prevent those who are not men, cisgender, white, heterosexual, etc., from occupying those spaces comfortably and meaningfully. As stated by Pérez (2020, p. 5) if our structures-although more horizontal and less hierarchical-are not transformed to eliminate heteropatriarchal relationships, and if we do not address the private sphere by acknowledging the shared responsibility of men and women in sustaining life, all this potential may become a trap for women.

The processes of feminist organisational change focus on organisations, implying a paradigm shift in how we ‘do gender’ and work with feminisms in social organisations. This is where connections are established with what was pointed out several decades ago from the Feminist Theories of Organisations. The COPEG processes aim to go beyond ‘counting bodies’ (Navarro, 2017) based on men and women in the organisation. This processes not only seek to adapt the organisation to the emerging realities but also, within the framework of alternative and transformative economies, to propose new forms of organisation and work planning, placing the sustainability of life at the centre of organisational identity and practice (Askunze-Elizaga, 2023).

Natalia Navarro defined feminist organisational change processes (or organisational change for gender equity) as ‘initiatives for organisational transformation that, with the aim of detecting and understanding how gender inequalities occur in organisations, propose to those who integrate them to review both the different aspects of their functioning and their experiences’ (Navarro, 2007, p. 7). The author uses the expression ‘hold up the mirror’ to illustrate the objective of these processes: to conduct an internal review of the organisation, of who holds the mirror, but also an external reflection.

The development of organisational change processes for gender equity (Navarro 2007, Decreto 40/2018) or the creation of liveable organisations (REAS Euskadi 2024, Piris et al., 2020) has become a central element of action in the Social and Solidarity Economy Network (REAS). In various regions and with different scopes, organisations are driving transformation processes to reveal how to build economies that serve life rather than capital and profit, or how to place life at the centre of our practices and organisations.

Initiating a process of organisational change for gender equity involves reclaiming the political dimension of gender analysis, which requires going beyond disaggregating data and using gender planning methodologies (Navarro, 2007), based on the premise that organisations are gendered and gendering (Acker, 1990). When discussing organisational change processes aimed at promoting gender equity, Piris et al. (2020) suggests adopting an integral, multi-level perspective. This approach implies that transformations should encompass various aspects of functioning, presence, and identity within the organisation, ensuring that changes are holistic and interconnected across all dimensions. The entities of social and solidarity economy have found in these processes of change a powerful tool to build new ways of being and doing business, more in line with their alternative proposals in the economic and social spheres (Askunze-Elizaga, 2023).

3.1. Expected changes applying Feminist Action Research approaches

Natalia Navarro proposes three aspects that, in general, all organisations fulfil regarding the gender perspective: the connection between personal and work life, the relationships established to achieve objectives (work model), and how power(s) is manifested, and participation occurs (Navarro, 2017). While the proposal generates a very interesting analytical framework, it is also true that organisational culture will shape the reality of organisations at a very concrete level, but it can always be observed through these three aspects.

Based on the work of Gender at Work (2024), Mugarik Gabe (2019), with the assistance of Natalia Navarro, refers to some aspects analysed and aimed to be changed in these processes:

Awareness of gender inequalities: The processes partly raise awareness among individuals in the organisation about the structural causes of inequality, its reproduction, and possible paths to eliminate it.

Resources: These processes propose initiatives aimed at redistributing and controlling resources (training, responsibilities, participation, information, budget, time...).

Organisational culture: This is clearly questioned with proposals for new values, symbols, or shared beliefs.

Institutionalization: So that the proposed changes persist, becoming institutionalized in the organisation: procedures, structure, decisions...

3.2. Guiding Action Research: some methodological premises

The methodology of organisational change processes could be classified as a kind of Action Research (Navarro, 2007), focused on reviewing organisational functioning and identifying aspects to change to transition towards more equitable and just organisations. The term ‘action research’ was introduced by Lewin (1946) to refer to a pioneering approach toward social research, which combined the generation of theory with changing the social system through the researcher’s active involvement in or interaction with the social system (Susman & Evered, 1978). While initially developed in the field of psychology, action research has become increasingly relevant in business and management contexts, as noted by Erro-Garcés and Alfaro-Tanco (2020) .

Therefore, organisational change processes share methodological similarities with Participatory Action Research (PAR) processes (an approach of AR focused on the participation of different communities along the research process), as they both focus on fostering a collective learning process and planning a series of actions aimed at transforming the reality they seek to address. Pajares (2019, p.12) emphasizes ‘the use of participatory methodologies based on the premises of action research and popular education to ensure a pedagogical as well as transformative approach’ as a key aspect of the process. Additionally, as highlighted by Lewin (1946) , the workshops conducted jointly by practitioners and scientists serve a triple function of action, research, and training (Lewin, 1946, cited in Susman & Evered, 1978).

PAR (Participatory Action Research) tackles real issues to generate knowledge and action, with a focus on empowering marginalized populations. This approach bases its legitimacy as science on philosophical traditions different from those that legitimize positivist science (Susman & Evered, 1978). Moreover, it promotes a form of knowledge that challenges hegemonic views of knowledge as an instrument of power and control (Boni & Frediani, 2020). On the other hand, PAR encourages action, as it aims to transform the initial situation of the group, organisation, or community (Greenwood & Levin 2007). It is characterized by participation, requiring social researchers to act as facilitators and members of local organisations and communities, with each taking certain responsibilities in the process, where all individuals are co-producers of knowledge. Finally, PAR has a significant cyclical component, promoting cycles of analysis-reflection and action, with great potential to generate emancipatory knowledge for all participants through a process of self-questioning and analysis of their own reality, making PAR an empowering methodology (Gaventa & Cornwall, 2008).

Moreover, PAR is conceptualized from a dialectical methodological perspective (Jara, 2017), which aims to establish criteria and methodological principles that allow articulating the particular with the general, the concrete with the abstract, and linking practice with theory. In this way, it understands reality and enhances the capacity to transform it. This dialectical methodological conception sees reality as a historical process in which ‘transforming reality’ means, therefore, transforming ourselves as well (Jara, 2017).

Feminist organisational change processes begin with an initial diagnostic phase (or self-diagnosis, in many cases) where the goal is to identify practices, operations, and/or beliefs that reproduce inequalities. After detecting these ‘stones’ or ‘pains’ in the organisation, work is done to design and plan actions (changes) at all levels with the aim of eliminating these inequalities (Navarro, 2007) and making organisations more ‘liveable’ (REAS Euskadi, 2019). Simultaneously, PAR follows a series of general stages and phases, which are very similar: project development, diagnosis, action plan construction, and, finally, implementation.

Some authors, such as Natalia Navarro, have employed the Tichy Framework, implemented in business development and management. This framework provides a ‘snapshot,’ an image of ‘how the organisation is,’ in this case, in terms of gender inequality. It considers three basic aspects: values, structure, and individuals within the organisation. These three elements are analysed from technical, political, and cultural perspectives, creating intersections and resulting in a matrix with nine cells. As mentioned on previous occasions, these processes, in themselves, never truly conclude. If the organisation is genuinely committed to feminist change and transformation, the need to review practices and operations will arise periodically.

Below, we will outline the methodology developed in the case of the organisational change process of XEAS País Valencià (XEAS PV hereafter), which was part of a broader research process within the framework of a doctoral thesis that implemented a Feminist Action Research methodology.

As mentioned earlier, this study aims to analyse the impact of the feminist action research methodology on processes of organisational change, based on the firsthand experience developed in Valencia, Spain, with the Alternative and Solidarity Economy Network of the Valencian Country (XEAS País Valencià, using its Catalan acronym).

4. Methodology

This section holds particular significance in this study, where a reflection is undertaken on the qualitative Feminist Action Research methodology that was employed to carry out the feminist organisational change process with XEAS País Valencià. The purpose of this section is to detail the phases and techniques implemented for the design of the process, with the aim of being replicated and analysed later. It is important to clarify that the process, which took place between September 2019 and December 2022, was framed within the context of the doctoral thesis of one of the authors of this work, who had a previous relationship and knowledge of the organisation before proposing the process. In this section, we will first explain what ‘XEAS’ is, and then proceed to detail the methodology and techniques employed in the process.

In order to recall the research objectives, this work aims to share the experiences of a Feminist Action Research project, highlighting its unique contributions compared to interpretative approaches. Furthermore, it explores how the methodology of organisational change processes contributes to the theories of ‘women in management’ and to the literature and methodologies of organisational change.

4.1. Research setting and context

The ‘Xarxa d’Economia Solidària i Alternativa del País Valencià’ is a second-level organisation that brings together entities from the Social and Solidarity Economy throughout the Valencian territory. XEAS PV primarily focuses on three main axes of action. Firstly, it serves as a tool for social and political impact through dialogue with political groups and administrations, promoting responsible public procurement, and building alliances with other organisations. Additionally, XEAS PV emphasizes strengthening network collaboration, fostering cooperation among entities in the Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE), disseminating SSE values, and driving territorial and sectoral development from an SSE perspective. Lastly, the network aims to consolidate SSE instruments such as ethical and alternative finances, encourage cooperation networks, and raise awareness of the values of SSE businesses.

XEAS País Valencià was a relatively young organisation, established in 2014, consisting of about 25 to 30 small entities. It operated with a weak organisational structure and limited financial resources to sustain various projects initiated by the network. In 2019, XEAS PV did not have a prior trajectory of specifically feminist work. To carry out the feminist organisational change process, the organisation lacked financial resources to support the self-diagnosis stage and the action plan.

The initial conversations with the organisation were facilitated, in part, by our prior connections with some individuals from XEAS País Valencià through previous work and activism, establishing a pre-existing trust. Therefore, in the initial meetings, we considered it appropriate to carry out an organisational review process for XEAS País Valencià as a whole (rather than focusing on one or two organisations within the network). XEAS felt they were at a crucial moment for diagnosing and proposing changes in the organisation and approaching it from a feminist economic perspective added an incentive. Thus, the process was designed and named ‘Towards a Sustainable and Caring XEAS PV.’

Since the beginning of the process (during the co-design phase), researchers from academia and some members of XEAS PV worked together on a steering group. The steering group functioned in a coordinated manner and convened every 15 days, utilizing an existing structure within the organisation (the cohesion commission) to allocate a specific agenda item for discussing the process.

The dual objectives of this FAR (Feminist Action Research) process were delineated from the outset during its proposal and the initial drafting phase, involving collaboration with the steering group before its presentation and acceptance by the organisation during the general assembly. From an academic standpoint, the endeavour was particularly compelling as it sought to investigate the potential contributions of Feminist Economics practices to Solidarity Economy organisations, identifying both theoretical synergies and practical gaps. Concurrently, for the organisation, the primary goal of the process was to create a forum for evaluating its identity, structure, and participatory dynamics.

4.2. Designing Feminist Action Research

In this work, we reflect on the research methodology employed in the investigation process conducted with XEAS País Valencià. In this section, we detail the methodology and techniques used, aligning with Feminist Action Research. We adopt a feminist paradigm, engaging in a dialogue with constructivist, participatory, and critical paradigms. Our epistemological stance is rooted in feminist principles, rejecting the dualities, rationalities, universalities, and objectivities often associated with knowledge. We advocate situated knowledge, recognizing it as partial, experiential, and practical in its construction. Thus, all individuals are acknowledged as subjects of investigation. This underscores the significant impact of researchers throughout the research process and emphasizes the importance of defining and situating our perspective from which we observe and actively participate in research processes. Hence, we position ourselves as researcher-facilitators and activists, embracing a perspective deeply committed to social transformation. We recognize research as an inseparable component of the social process, intricately woven with power dynamics and conflict. Therefore, we advocate for a dialectical and dialogical research approach, emphasizing participation, collective reflection, and dialogue. From an intersectional feminist perspective, we highlight the importance of critically addressing participation and dialogue, acknowledging that all spaces, including those for knowledge creation, are influenced by power structures that often reproduce inequalities.

Qualitative social research is highly diverse, allowing us to focus on the process of analysing and interpreting discourses and deeper meanings of reality (Ibáñez, 1994), employing a profound approach to data. According to Denzin and Lincoln (2018, p. 46) , qualitative research ‘constitutes a field of inquiry that crosses disciplines, areas, and objects of study’, understanding it as a ‘situated activity that positions the observing person in the world (...) consisting of a series of material and interpretative practices that make the world visible and transform it’ (Denizip.48). However, the authors emphasize the diversity of qualitative research, supporting numerous practices and covering multiple disciplinary histories, methods, and approaches.

The Action-Research (AR) encompasses a wide range of approaches and methods that emphasize the practical dimension of knowledge and the involvement of participants in its production (Martí, 2017). Thus, the ultimate purpose of AR is to build performative knowledge and promote locally relevant change. Therefore, AR does not end with new findings and perceptions but continues through engagement in action (Park, 2006 in Martí, 2017). Within the AR approaches, Participatory Action Research (PAR) is found, which, as indicated by Kemmis and McTaggart (2005) , has distinctive characteristics, primarily being relational and participatory. According to Rodríguez et al. (2000), PAR is a ‘method of study and action that seeks to obtain reliable and useful results to improve collective situations, based on the participation of the collectives under investigation’ (p.47).

Although action research (AR) has been developed more extensively in social science fields as sociology, social work, and local development, Erro-Garcés and Alfaro-Tanco (2020) underlined AR as a meta-methodology that has been and can be developed in the management field as well. The authors argue that AR is an umbrella process that is flexible and helps to incorporate different methods in the corresponding faces.

Expanding on this conception of PAR, Marta Luxán and Jokin Azpiazu, in their manual ‘Feminist Research Methodologies’, define Feminist Participatory Action Research (FPAR) as a form of research where the four letters that make up the concept problematize the research process itself (Luxán & Azpiazu, 2016). According to them, in FPAR, research objectives are not limited to knowledge production; instead, a certain level of action and change in reality is sought through the research approach, going beyond any collateral impact of the research. FPAR provides a profound critique of the extractivist dynamics of academia concerning communities and social groups and draws inspiration, among other sources, from popular education. Therefore, it is considered that ‘people have a right to participate in the production of knowledge, which is a disciplined process of personal and social transformation’ (Freire, 1997, p.487), and this process is articulated as a dialogue with co-researchers and co-subjects of research. It proposes research ‘with,’ so the results and actions respond to the desires and needs of the involved groups and individuals, considering needs from the perspective of social change.

Continuing with the proposal of Luxán and Azpiazu (2016) , we will refer to a feminist methodology as one that embraces and integrates critiques from feminist epistemologies, contributing a methodological perspective to feminist theories. This methodology recognizes and values aspects such as the subversion of the subject-object relationship, the breakdown of the public-private dichotomy, highlights the interdependence between theory and practice, acknowledges the existence of power relations, and seeks to transform them or advocates for the collective production of knowledge, among other considerations.

4.3. Applying Feminist Action Research

As mentioned earlier, this work aims to analyse the methodology carried out following the proposals of a Feminist Action Research methodology. Although neither the participants nor the researchers initially recognized it as such, during the process’s evolution and the search for theoretical and methodological references, the methodology took shape following these principles. The work with XEAS País Valencià as part of this research process was born with a clear orientation towards action, understanding research as one more tool for social transformation, and also with a feminist approach in terms of understanding, conducting, and experiencing research. In this case, participatory and more hermeneutical techniques are articulated: participatory workshops, participant observation, interviews, and documentary review.

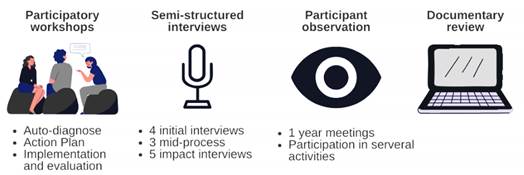

In the analysis process, semi-structured and in-depth interviews, participant observation (using the researcher’s log instrument), facilitation of participatory workshops (diagnosis and development of an action plan), and documentary review were articulated. In total, 12 interviews were conducted, and three moments were established to carry them out. Thus, four initial interviews were developed to contextualize and better understand the organisational reality before starting the process, three interviews mid-process to learn about the initial reactions, feelings, and changes, and five interviews one year after completing the workshop stages to assess the impact of the process on the organisation.

Additionally, some researchers facilitated the process through a series of participatory workshops for the development of the initial phases (diagnosis and action plan development) and conducted thorough participant observation. The facilitation of the participatory process with XEAS País Valencià took place over a year, with a series of working sessions lasting 2 or 3 sessions (3-4 hours each) on weekends in Valencia. The exhaustive documentary review has been a technique used in the design and diagnostic stages of the organisational change process. The Figure 1 represents the combined techniques conducted during the Feminist Action Research process.

The analysis of all collected information, gathered through various techniques, took place at different stages, with the main phase concentrated over two months during the summer of 2022. The interview transcripts, stored only in audio recordings, were conducted using the online software O’Transcribe by one of the researchers with the assistance of a colleague. These interviews have been stored in a cloud accessible exclusively to the researchers and then transferred to NVIVO. The transcription has not been shared with the interviewees as none suggested or required it.

The primary data analysis was conducted using NVIVO software, which facilitating qualitative analysis by organising documents, creating labels, data categories, and interviewee profiles, among other functions. This tool proved instrumental in coding and initially categorising diverse materials, including workshop materials, transcribed interviews, field notes, and internal and public documents from organisations.

An ETIC-EMIC analysis was employed, with predetermined analysis codes established at the outset based on the research questions. These codes focused on organisational changes resulting from organisational change processes and factors influencing or constraining their transformative capacity. Initially proposed codes were introduced into NVIVO software for the first round of coding across all analysis materials. Subsequently, some sub-coding and recoding occurred as new ideas emerged, although the initial proposal remained largely unchanged. The codes utilized in this study reference a broader research process, as this study is part of a doctoral thesis process with broader research objectives. These objectives encompass not only the contributions of the methodology but also an analysis of organisational changes. This is the reason why we considered avoid its inclusion to this paper.

After the initial coding in NVIVO, the results were categorised and analysed. This analysis was carried out individually, mainly due to time constraints associated with a doctoral thesis. However, a session for the socialisation and collective review of research findings with XEAS País Valencià, aiming to facilitate sharing and discussion of these results.

It is important to clarify that the analysis process was based on transcribed interview data, as well as workshop materials, research logs, and participant observation experiences, in addition to reviewing documentation from both organisations.

5. Results

In this section, we present the outcomes obtained throughout the research process, detailing the observed transformations within the organisation XEAS País Valencià. These results reflect the tangible and intangible consequences stemming from the implementation of the Feminist Action Research (FAR) methodology. Through a thorough analysis, we examine the different areas of impact, from changes in organisational culture to political and technical transformations. These findings not only provide a profound understanding of the evolution of XEAS but also contribute to the growth of knowledge in the field of feminist research and organisational change processes. We integrate our analysis of the results with primary data obtained mainly from the interviews. To offer a comprehensive overview of the interviewees, the Table 1 summarises their codes and profiles.

5.1. Transformation of XEAS País Valencià with Feminist Action Research

The primary outcome of the study was the initiation of a feminist organisational change process, facilitated through collaboration among various stakeholders within the organisation (XEAS PV) and academia. The research spanned a period of three years, with a more intensive collaboration with XEAS PV occurring over one year. Despite the formal conclusion of the research, ongoing collaboration and engagement persist, and the organisational process has continued, significantly impacting the reality of XEAS PV.

The process facilitated with XEAS País Valencià aligns with the methodology of feminist organisational change processes, as outlined in the introduction of this article. The sessions (workshops) within the process typically lasted between 3 to 4 hours and were conducted over several weekends in the city of Valencia.

In the case of the ‘Towards a Sustainable and Caring XEAS PV’ process, a steering group was established to define objectives, determine locations, and maintain close communication to tailor the work sessions accordingly. This group included three women experts in feminisms and participatory processes, an activist from the network, and a longstanding participant in XEAS, working collaboratively with the researchers. The group held bi-weekly, in-person meetings in Valencia on Thursdays, where the process took precedence as the first agenda item. During these meetings, we engaged in discussions, planning, and evaluations of the participatory process. The steering group also served as the communication link within the network and acted as the contact point with the governance group. Additionally, during these meetings, the group made methodological decisions, such as defining the ‘Responsible Adherence Pact to the process’ and proposing dates, duration, and locations for the sessions.

Table 1: Interviewees coding and profile

| Initial | EI1 | Member of an entity (specialised in feminisms) with less than 1 year in XEAS. Female, aged 25-35. |

| EI2 | Volunteer (unaffiliated to any entity) with less than 2 years in XEAS. Male, aged 25-35 | |

| EI3 | Technical secretary and affiliated to XEAS for more than 2 years in the Alicante group. Female, aged 25-35. | |

| EI4 | Member of founding entity. Organisational veteran, board member, and governance member. Male, aged 45-55. | |

| Midway | EM1 | XEAS member for more than 3 years, with various affiliations (member, volunteer, etc.). Female, aged 25-35. |

| EM2 | Member of entity for more than 3 years in XEAS. Recent president and part of governance. Male, aged 45-55. | |

| EM3 | Volunteer and member of a former XEAS-affiliated entity. Longstanding involvement in the organisation. Female, aged 35-45. | |

| Final | EF1 | Member of an entity with less than 2 years in the network. Participant throughout the process. Female, aged 25-35. |

| EF2 | Member of an entity with less than 5 years in the network. Participant in a significant portion of the process. Male, aged 25-35. | |

| EF3 | Member of an entity recently incorporated into the network. Participant in the execution phase of the process. Male, aged 25-35. | |

| EF4 | Member with a leadership position, involved throughout the process. Male, aged 45-55. | |

| EF5 | Member of an entity not participating in the process but holding a position in the technical secretariat. Female. 35-45 |

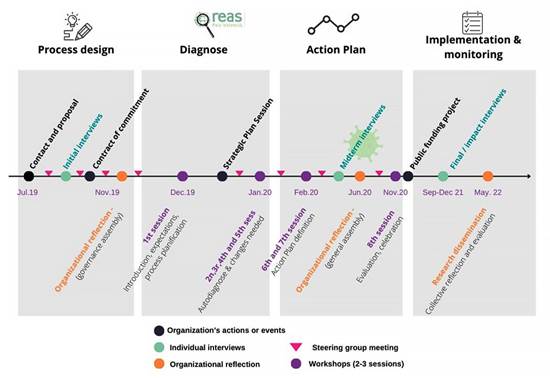

The research process unfolded across distinct phases. In the initial introduction and design phase, preliminary interviews and meetings were conducted to strategize the process, establish timelines, schedules, and delineate objectives. This phase played a pivotal role in disseminating information throughout the organisation, elucidating the impending course of action, and extending invitations to member organisations for participation. The self-diagnosis stage encompassed three workshop sessions, supplemented by preliminary interviews. Identification of key areas earmarked for transformation within XEAS PV’s organisational structure led to two sessions dedicated to designing an action plan that would usher in the requisite changes. However, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic prompted a prolonged hiatus of five months before workshop activities could recommence. Fortuitously, during this interlude, the organisation concentrated efforts on securing financial support. A project undertaken during this period facilitated the implementation of select actions outlined in the Action Plan. Concurrently, online interviews were conducted, constituting the sole instance of virtual engagement.

The Action Plan focused on four priority action lines and two cross-cutting actions that XEAS PV deemed essential to build a more liveable, more feminist organisation. The primary action line focuses on fortifying the network’s identity and internal capacity through specific initiatives, including training sessions encompassing the principles of the solidarity economy, networking, decision-making processes, horizontal organisational management, and the distribution of roles and responsibilities within groups. The second line of action concentrates on delineating the structure and functionality of XEAS PV in alignment with its foundational principles, with a particular emphasis on ensuring sustainability. This involves the formulation of a strategic plan, the dissemination of the feminist and strategic plan process across the entire network, and the establishment of an internal operational framework.

The third action line is dedicated to instituting inclusive and equitable forms of participation and decision-making, addressing power dynamics responsibly. Activities within this domain encompass the retrieval of pertinent documents and tools from other organisations, the creation of nurturing spaces during meetings, advocacy for collaborative work in small groups, definition of participation modalities, integration of roles in meetings, and the provision of training to entities regarding organisational structures and decision-making processes.

The fourth action line aims to enhance network cohesion by incorporating emotional elements, including historical reflections within the organisation, organising celebratory events during various productive network meetings, implementing protocols for welcoming and departing members, and formalizing emotional sharing sessions. As transversal strategies, the proposal suggests developing mechanisms for territorial rotation and formulating funding strategies for the network.

Subsequently, a concluding session marking the termination of the process and an evaluation of the initial ‘journey’ year transpired, revealing nascent transformations. Post this closure, the organisation sustained its commitment to the process, interspersing training sessions, additional working sessions, and forums led by subject matter experts. A year later, interviews were conducted to appraise the impact of the process, culminating in a feedback session on the analyses conducted by the research team. Figure 2 encapsulates the entirety of the process, exemplifying a sophisticated amalgamation of diverse techniques underpinned by collective elaboration and design, emphasizing a resolute commitment to actionable outcomes.

5.2. Unveiling the main transformative changes through Action Research

While not the primary focus of this study, it is deemed crucial to provide a detailed account of the transformations instigated by the organisational change process. This endeavor is pivotal for a nuanced comprehension of the process’s impact. As acknowledged earlier, such transformative processes, when executed with due diligence, lack a definitively demarcated terminus, posing challenges for immediate impact assessment. Nevertheless, to discern specific alterations and facilitate comprehensive dissemination, we have systematically classified them into three tiers: political, technical, and cultural shifts, aligning with the taxonomy introduced by Natalia Navarro (2007) .

We observed that the technical changes were more visible and could be rapidly implemented. The most outstanding technical changes of the analysed experiences are the mobilization of resources to boost the actions of the process and feminist projects, the change in the structure and redistribution of tasks and responsibilities, and the creation or renewal of internal protocols and procedures. At first it seemed that there were working commissions and then it turns out that they were small nuclei with enthusiasm, but without a real force behind them and without really knowing who they will count on. What’s more, the bands had a certain life, but usually there was no continuity and that was very frustrating. EF4

It has been proven that political changes could be developed in the short and medium term, but it will depend on the evolution of the process and the depth of the reflections and political will of the organisation. In general, we see how feminisms gain a greater presence in the projects and activities and become part of the organisational identity more consciously. Thus, feminisms and the changes proposed have greater legitimacy after going through these processes. One of the most key things that I see, is that we have learned to take care of ourselves and to see this perspective that we are working on and the entities that are not there nothing happens. In other words, we grant ourselves legitimacy. EF4. In addition, the organisation becomes a benchmark for others, what enables the opportunity of multiplying its scope. These political changes may be easily carried out if there are not quite explicit resistances, but it is a challenge to not remain on a discursive level and to become part of the organisation’s identity. It has been a priority in the past few months and now it is something else that we talk about and have incorporated, but it is in danger of being a little... that is, to be the most important thing again. Although some dynamics and paradigm shifts remain ‘yes or yes’. EF2

When it comes to cultural changes, they are the most burdensome to identify in the short and medium term because culture, beliefs and attitudes depend not only on collective changes, but also on the individual processes. Regarding the cultural changes observed, there is evidence of greater importance and recognition of emotions and reproductive tasks, the deconstruction and questioning of productivity ideas and the ‘heroic militancy’. If I see it from the outside and I see the work and the evolution then I think it has been very important. Seeing people who were really burned out, who didn’t know how to loose, who were doing things wrong and then being able to recognize all that... Well, it’s valued. EF3. Responsible leaderships and different levels of participation started to be developed or tried to be. Another important feature to highlight is that thanks to the process and formative actions, the gender perspective is expanded and problematized together with other systems of oppression, paving the way to a work of euro-white, heteronormative deconstruction. The organisation has learnt to relate to change as a process itself, breaking with the vision focused only on tangible results. Then to continue the process I don’t know how we are going to do it, but somehow we were always there with the issue and discussing it. EF4

At the level of individual consciousness, cultural changes are also extensive in these processes. People who participate experience multiple learnings that stimulate processes of reflection and transformation of their attitudes and beliefs. The issue of heteropatriarchy and hidden sexism and all that, and the same recognition that some of us made of our inability to sometimes not even be aware of it, right? EM2. Some personal changes experienced in these processes are: the identification of power in the organisation, the recognition of the potential of conflict and not as a threat, the identification and rejection of patriarchal attitudes and practices and the vision of feminism as the path to transformation.

5.3. Transformative effects through the lens of Feminist Action Research

This process embraced participatory methodologies during the collective workshops it conducted. This methodological choice is not arbitrary and, indeed, emerges as a catalyst for organisational changes at both personal and collective levels within the processes. Departing from the conventional assembly dynamics of organisations has led all participants to position themselves differently within the group, instigating manifold transformations and ushering in novel ways and opportunities to express opinions and emotions. As stated one participant: I think that kind of dynamic put us somewhere else and made things come out that maybe wouldn’t have come out otherwise. EM1

These dynamics not only serve the achievement of objectives such as organisational reflection and revision but also prioritize play, humour, and movement as expressions of thought. Thus, in a way, they signify a departure from more conventional, productivity-oriented, and commercialized goals typically associated with classical organisational change processes.

Furthermore, this methodological proposal draws inspiration from feminist epistemologies, popular education, and participatory techniques. Its influence extends beyond the overall process to characterize each of the collective work sessions conducted during the diagnostic phase and the drafting of the action plan, earning commendations from numerous participants. You used audiovisual media, group dynamics, cohesion dynamics that made it easier to get to know each other. The fact also that after a session we stayed to eat, because it makes you suddenly feel next to someone and start to know what that person does. They were spaces to know us that it was a space that we needed and that also needs a lot of REAS, spaces of cohesion, of getting to know each other, of having nothing else to do but be together and chat. I think it’s key for something to work and in this whole process it could be done and it was super cool. EF1

6. Discussion

The work aimed to share insights from a Feminist Action Research project, highlighting its unique contributions compared to interpretative approaches. Additionally, it explored how the methodology of organisational change processes contributes to ‘women in management’ theories and organisational change literature and methodologies.

In the current landscape of organisational research, the importance of qualitative research methods has become increasingly pronounced, particularly for delving into the nuances of context-specific organisational and social realities (Braun & Clarke, 2013; Contreras-Pacheco et at., 2024; Denzin & Lincoln, 2018; Garcia & Gluesing, 2013; Yin, 2014). The call for greater orientation towards qualitative approaches aligns with the ethos of Action Research methodologies, emphasizing an in-depth understanding of the lived experiences and complex dynamics within organisations.

This emphasis on qualitative methods resonates with recent discussions in specialized literature regarding their acceptance and prominence within leading journals in business management (Bluhm et al., 2011; Üsdiken, 2014). The inquiry into whether qualitative methodologies have gained more recognition underscores a broader shift towards appreciating the richness and depth that qualitative research can bring to the understanding of management and organisational phenomena.

Against this backdrop, the findings of our study reinforce the value of embracing Feminist Action Research within the domain of organisational management. The participatory and reflexive nature of this methodology aligns seamlessly with the calls for qualitative approaches, offering a robust framework for exploring the intricate interplay of power, gender, and organisational dynamics. By integrating Feminist Action Research into the discourse, we contribute to the ongoing dialogue surrounding the evolving landscape of research methodologies in management studies.

Moreover, the contributions of this methodology extend beyond the realms of academia, resonating deeply with the imperative for organisational and societal change. By situating itself within the framework of ‘gendering organisations,’ (Acker, 1990; 2006, Calàs & Smircich 2016) the methodology aligns with broader discussions on organisational inequalities and the reproduction of gender within institutional structures. Through its emphasis on reflexivity and inclusivity, Feminist Action Research offers a nuanced approach to organisational change, one that acknowledges and confronts existing power differentials while striving for more equitable outcomes.

Furthermore, the insights gleaned from this study shed light on the transformative potential of organisational change processes guided by feminist principles. By foregrounding issues of power, privilege, and gender dynamics, these processes challenge traditional notions of organisational hierarchy and offer pathways towards more egalitarian structures. By engaging in critical reflection and collective action, organisations can begin to dismantle entrenched systems of oppression and embrace more inclusive models of governance and decision-making.

This research underscores the importance of adopting a feminist lens in organisational change processes, highlighting the need for more inclusive and equitable approaches to management. By centering the experiences and perspectives of marginalized voices, organisations can cultivate environments that promote diversity, equity, and social justice, ultimately fostering more sustainable and resilient organisational cultures.

7. Final considerations and learnings

The impact of participatory feminist methodologies in this research process stands out significantly when compared to more conventional consulting approaches, where diagnoses and actions are often conducted externally. This distinction is important as it underscores the transformative potential of methodologies that actively involve the organisation’s members, allowing for a more profound engagement with the change process.

Unlike traditional externalized approaches, participatory feminist methodologies facilitate a more inclusive and empowering organisational change experience. By involving the members in the diagnosis and action planning, these methodologies foster a sense of ownership and agency among the organisational stakeholders. This participatory engagement not only enhances the relevance and specificity of the proposed actions but also contributes to the long-term sustainability of the organisational changes.

Moreover, the success of feminist organisational change processes is contingent upon the adoption of a feminist and participatory methodological approach. This approach challenges the conventional top-down consulting models by prioritizing collaboration, reflexivity, and the co-creation of knowledge. In doing so, it not only addresses immediate organisational challenges but also lays the groundwork for a more egalitarian and resilient organisational culture.

This methodology points out directly to the rational, objective and neutral forms of exploration of other organisational change processes made, for instance, by consultants without the members of the organisation. Thus, these processes recognize and value the epistemology of emotions, developing a dialogue and encouraging a reflection beyond words, showing that this methodological commitment is also political. It is no coincidence that the methodological strategy of this thesis also aligns with feminist epistemology and research, rather an effort to give coherence to this work, following the objectives of both research and action.

For future research, it would be interesting to promote feminist organisational change processes in other types of organisations, such as associations, social movements, or companies. It would also be a challenge to propose a feminist organisational change process in a (conventional) company that has no prior feminist work. Along these lines, we consider that the results of this research can be beneficial for a wide variety of organisations and groups. Similar change processes can be adapted in terms of time, methodologies and strategy to generate consistent actions considering the reality of each collective. Thus, although in this work we have analyzed second-level organisations, we think that the reflections can also be extrapolated to first-level organisations.

This research not only underscores the transformative potential of Action Research methodologies within management but also speaks to the broader methodological shifts in the field, advocating for a more nuanced, context-specific, and qualitative understanding of organisational realities.