Family conceptualization and dynamics within the family context have changed in the last decades. Social, cultural and economic transformations lead to new family structures and trends in men’s and women’s roles in society and in the family. Parental roles in the new family structures have become a topic of inquiry for many scholars in current family studies.

However, literature on family relations during the past decades has focused on the mother as the main parental figure. This emphasis is probably related to the traditional assumptions associated to the nuclear family structure; in some societies the “ideal family” is a type of family with two parents (a mother and a father) and their children.

Parents within these families play specific and well-defined roles. Under this type of family men usually play the role of economic providers, with little or no involvement in other aspects of family life or children’s development.

Women in this family structure are in charge of most family activities and play the role of the main caregiver for children; they are considered the main source of socialization and the active agent in children’s lives (Parke, 2013). The negligence regarding paternal figures in family literature was outlined during the 80’s by researchers such as Lamb (1975, 2010), Daniels & Weingarten, (1988), and Pleck (1997), among others. This was due in part to psychological theories on parenting that dominated at that time (i.e. biological theories and psychoanalytic theories). Researchers called for a more comprehensive conceptualization of the family in which all its members play an active role and influence each other’s development and well-being (Parke, 2002, 2004; Rohner &V eneziano, 2001).

Latin American countries have witnessed numerous social, cultural and economic transformations during the last four decades; these changes have impacted the conceptualization of family, the characteristics of family dynamics, and the social representations of fathers and mothers in this social unit. During the 20th century familias in Colombia followed a patriarchal model, which is characterized by a traditional division of gender roles in which women are responsible for housework and child care (private sphere), and men have the main responsibility outside the house, in the workplace, and social context (public sphere) (Moreno, 2013; Pachón, 2007; Viveros, 2002, 2007).

In the last decades several studies show evidence of some social and cultural changes that have transformed the roles of men and women in the families. Despite those changes, there are still strong pressures imposed on men and women regarding their roles both within the family and in social contexts, which make maternity and paternity a difficult task at the present time. Some questions may emerge from these changes: What is the impact of these transformations on fathers’ roles in the family and with their children in this country? Are the changes evident at a macro systems’ level (in social and cultural values, norms, gender and generation stereotypes)? Do they influence mothers’ and fathers’ attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors within the family, and in their involvement with their children?

In recent years, results from studies on the role of the paternal figure in the family micro- system show that the quality of the relationship with the father influences children’s quality of relationships with their siblings, and children’s psychological adjustment (Ripoll, Carrillo, & Castro, 2009). Additionally, positive relations with the father have unique and significant effects on the quality of life of male and female adolescents and young adults (Carrillo, Ripoll-Núñez, Cabrera, & Bastidas, 2009). Lastly, findings from studies comparing the effects of children’s relationship quality with fathers and mothers on their functioning indicated that positive characteristics of the father-child relationship such as affective security and positive involvement have a significant effect on children’s quality of life in biological and stepfamilies (Carrillo, Ripoll, & Schvaneveldt, 2012). However, findings regarding the characteristics of fathers’ roles, the specific dimensions of their involvement with their children’s lives, and the implications of fathers’ involvement on children’s development in Latin America and in Colombia, are still limited.

The purpose of the current qualitative study was to explore fathers’ perceptions about their role in the family and the characteristics of fathers’ involvement in their children’s lives in the Colombian context. Specifically, the study addressed the following research questions: What are fathers’ beliefs about current maternal and paternal roles in the family? What are fathers’ perceptions of their role in the family and with their children? How do Mathers perceive their involvement in their children’s lives?

Family: Conceptualization and Social Transformations

In Latin America, the nuclear family was the dominant structure in the 19th century and a large part of the 20th century; this family type was characterized by a patriarchal structure where men had a central and leading role within the family group (Therborn, 2007). In the second half of the 20th century a number of social, cultural and economic transformations took place, which had a decisive influence on the conception of family, its functions and role in society, and on the relationship dynamics generated in the different subsystems that integrate it. Some of the changes families in Colombia have experienced in the last decades include: A delay in age at marriage, as well as in the age people become parents; an increase in women’s access to higher levels of education, and in their involvement in the workforce; a reduction in family size; a significant increase in separation and divorce rates; a major move towards urbanization; and secularization of religious beliefs regulating individuals’ private lives. These changes have resulted in important transformations in men’s and women’s roles in the family context and maternity and paternity (Carrillo, Ripoll & Schvaneveldt, 2012; Gutiérrez de Pineda, 1983; Puyana & Mosquera, 2005).

In different social contexts, the roles of men and women in the family changed as the result of those transformations and new forms of organization emerged, which imposed a variety of family structures on society. The traditional portrait of fathers as economic providers and authority figures began to alter to economic providers and supportive figures that express affection to their children (Greven cited by Day & Lamb, 2004). Although nuclear families remain as the most common type of families, other structures emerged and assumed an important place in society (Parke, 2013). Particularly in Colombia, data from a study on the evolution of family typologies in the last two decades, indicate that the percentage of nuclear families decreased from 65.5 % en 1993 to 60.7 % in 2014.

Additionally the rate of two-parent households headed by women increased from 4.1% en 1993 to 12% in 2014; this change indicates a change in women’s role in social and economic, as well as in family contexts (Departamento Nacional de Planeación [DNP], 2014).

Although research on fathers in Latin America is scarce, in the last decades there have been some studies exploring the meaning of fatherhood in different cultural contexts. For example, Puyana and Mosquera (2005) examined the impact of social changes on the meaning of parenthood for men and women in Colombia. They identified three main trends in family types in Colombia: First, a traditional type in which the father is depicted as a provider whose essential task is to obtain financial resources for his family, while the mother’s focus is on childcare. The second trend was called families in transition; where men began to question the social representation assigned to them as economic providers, and intended to build a fatherhood based on a close emotional relationship with their children. Women, on the other hand, do not conceive motherhood as their unique developmental task, and include professional and personal goals as developmental alternatives. This trend involves the coexistence of traditional and innovative beliefs and social representations, and a search for greater gender equality, more loving and close father-child relationships, and more democratic authority (Puyana & Mosquera, 2005). In the last tendency, called the “rupture trend”, men are moving toward new customs of fatherhood in which they actively participate in raising their children. The term rupture refers to an opposed attitude to the child-rearing models they underwent in their families of origin, and their desire to build innovative relationships in their current families.

Puyana (2003) also examined the prevalence of these trends in different regions in Colombia; she found that “parents in transition” was the most common category observed in big cities where urbanization and economic development has shown an accelerated growth in the last decades. In small cities as well as in rural areas the traditional type of families was more frequent. Moreover, the transitional and rupture trends were common in families with middle and upper-middle socioeconomic status (SES), whereas the traditional type was common in families with low SES; higher SES families showed both the transitional and traditional trends (Puyana & Mosquera, 2005).

Studies in other Latin American countries suggest similar typologies of families regarding gender roles and parental tendencies (Torres-Velázquez, 2004; Valdés, 2009).

The determinants of fatherhood: Beliefs and Father Involvement

The determinants of parenting have been well described in the literature of family studies by recognized researchers. The quality of parenting varies, depending on a complex set of individual, relational and contextual variables.

Individuals’ beliefs about their role as parents and about the way they get involved in the family, constitutes one of the important determinants of parenting. These beliefs are part of the cognitive aspects of parenting and are closely related to the way parents are involved in the family and with their children (that is in parental behaviors and child-rearing practices) (Belsky & Vondra, 1989; Parke, 2002).

Beliefs about parental roles. According to Social Cognitive Theory, beliefs and expectations influence the degree of success in achieving a specific behavior (Bandura, 1997). Fathers’ beliefs are a set of ideas they have about their role in the upbringing and development of their children. These beliefs may be influenced by individual factors

such as personality traits, personal rearing history, and characteristics of interactions with own parents; but they may also be affected by social and cultural variables (Turiano, 2001). Some researchers point out the importance of beliefs in the study of fathers’ roles in the family; they emphasize the need to understand the cognitive processes that are involved in fathers’ behavior and how these processes may affect the development of their children (Belsky, 1984; Parke, 2000).

The meaning parents assign to their roles as fathers or mothers derives from cultural expectations, values and ideas imposed by society regarding gender relations; therefore, men construct their masculinity and fathering according to those expectations and beliefs (Puyana, & Mosquera, 2005). Findings from a qualitative study with Colombian parents conducted by these authors showed that parents with traditional beliefs highlighted the importance of responsibility and protection in fatherhood, and tended to assume the provider role in their families.

Additionally, beliefs about good interactions with their children were considered essential to fatherhood for highly educated fathers; this group of fathers reported the need to express positive emotions and to establish close relationships with their children within their central beliefs of fathering. Finally, fathers with more egalitarian gender role beliefs tended to divide household tasks with their partner in an equivalent manner and provided more emotional support to their couples during pregnancy, furthermore, they participated more in child raising activities. In similar studies, researchers have found that most fathers believed their main responsibilities were to educate, care for, and provide basic needs for their children, and maintain good, loving and supporting relationships with them (Olavarría, 2003, 2014; Pachón, 2007; Solís-Cámara & Díaz, 2007; Torres, Garrido, Reyes, & Ortega, 2008).

Men’s beliefs and ideas about parenting crucially affect the role they assume within the family, the type of relationship they seek to establish with their children, the way tasks are divided at home, and the responsibilities they tend to assume in the upbringing of children.

Father involvement. In the mid-seventies and early eighties developmental psychologists and other researchers drew attention to new family dynamics; different investigators drew attention to the importance of the role of the father in the family, men’s involvement in child-care activities, and the influence of fahters’ family participation on child development (Lamb, Pleck, Charnov & Levine, 1985).

Fathers’ involvement was initially conceptualized as a uni-dimensional construct and it was assessed through single measures such as the number of hours they spend in family or children’s activities. Studies focused on comparisons between mothers’ and fathers’ activities with the children (Jacob, Moser, Windle, Loeber, & Stouthamer- Loeber, 2000). Some of the first studies that include father figures concentrated on the negative consequences of father-absence on children (Lamb, 2010). Evidence of changes on fathers’ involvement in the family motivated new lines of research that explore issues such as child development differentials depending on family structures, and direct

influences of fathers’ characteristics and involvement on children’s cognitive, social and emotional development (Lamb, 2010; Leidy, Schofield, & Parke, 2010; Mosely & Thompson, 1995; Tamis-Lemonda, Baumwell & Cabrera, 2010). These studies broadened the conceptualization of fatherhood and paternal figures in the family and emphasized different ways in which a father could get involved in the care and raising of his children (Roggman, Fitzgerald, Bradley, & Raikes, 2002).

As research on fathers unfolds, a new conceptualization of father involvement emerged. Lamb, Pleck, Charnov, and Levine (1985) proposed a multidimensional view of this construct with 3 specific components: interaction, availability, and responsibility. Interaction referred to the direct contact between father and children through specific care and play activities; availability was related to the skills fathers used in their interaction with them; and responsibility refers to the organization of resources and activities to ensure adequate childcare (i.e. asking for medical attention, seeking sites for childcare or being aware of the physical resources needed).

Pleck (2010) revised the construct and suggested it comprises five dimensions: involvement in positive activities, warmth and responsiveness, control, indirect care, and responsibility process. It is important to highlight that recent literature on fatherhood goes beyond the components of father involvement to more ecological analysis of fathers’ participation in the family, which includes individual, relational and contextual variables. Aside from the specific dimensions of his involvement, scholars evaluate fathers’ roles associated to other variables such as motivation, skills and self-efficacy, perception of social support, and family and institutional barriers related to this involvement (Pleck, 2012; Roggman, Bradley, & Raikes, 2010).

Method

Sample and procedures

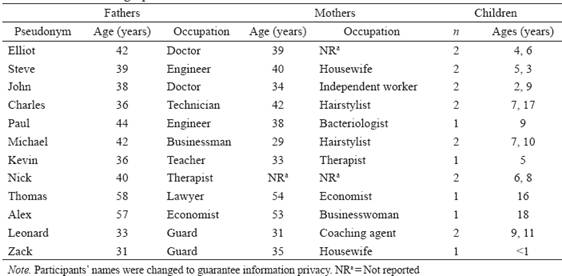

Initially, 18 Colombian fathers living in Bogotá were invited to participate in the study. The final sample comprised 12 of them because they met the selection criteria and they were available for the interviews. Fathers filled out a consent form to participate in the study. Participants’ ages ranged between 31 and 58 years; their wives’ ages ranged between 29 and 53 years. Sixty-six percent of the fathers had college degrees, 8% were technicians and 25% had high school diplomas. Regarding the wives, 16% were housewives and 66% worked outside their homes. Description of participants’ socio-demographic information appears in Table 1. Participants were recruited through different methods: brochures in daycare and preschool centers, invitations through students, and snowball strategies. In order to participate in the study fathers had to meet the following criteria: 1) Fathers should be at least 26 years old to avoid having adolescent or young adult fathers in the sample. 2) Fathers should have a marital relationship and be living with their couples. 3) Families should have between 1 and 3 chlidren. 4) Children’s age should be 18 years or less .

The present study followed the ethical standards defined in Resolution # 008430 (1993) from the Colombian Ministry of Health. Fathers filled out a consent form to participate in the study. The form included a presentation, as well as, the ethical concerns of the study. Specifically, they were informed about the confidentiality of the information, the voluntary character of their participation, and the need for their permission to audiotape the interviews.

Participants were contacted by telephone to schedule a convenient time for the interview. Two students visited each home and conducted the interview. Students and research assistants who participated in the data collection phase were previously trained on in-depth interview techniques. The training consisted of two role-play sessions in which students familiarized themselves with the instrument and had the opportunity to practice interview skills. Interviews were conducted at participants’ homes or workplaces and lasted between 45 and 60 minutes; they were audiotaped with participants’ consent to facilitate the transcription process and the analysis phase. Interviews were transcribed verbatim.

Instrument

Depth-interview. Information was gathered through an in depth-interview designed by our research group at the Psychology Department (Los Andes University - Bogota). Undergraduate and graduate students participated in the different phases of the study. The interview had two sections:

Socio-demographic information. This section involved aspects related to participants’ age, occupation, marital status, number of children, and children’s ages. Socioeconomic status was obtained through the location of the family’s residence.

Fathering themes. This section included questions regarding beliefs about fatherhood, the roles of fathers and mothers in the family, and the father’s involvement in their children’s lives. For instance: how would you describe yourself as a father? How much time do you spend with your children throughout the week, and what kind of activities do you enjoy together? What characteristics should a good father have? What is the role of a father with their children? The included themes were based on interview topics to study fathering trajectories, suggested by Marsiglio (2004).

Data analysis

Grounded Theory was used to analyze the interview data. This theory was developed by Strauss and Corbin (1994) to carry out qualitative analysis in order to identify possible relationships among different concepts embedded in the data. By using the assumptions of Grounded Theory, researchers aim to discover processes and patterns of interactions that characterize individuals’ narratives of a particular research subject and to construct new theoretical concepts that explain deep relations reflected in the data collected during the study (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). Data saturation was achieved by: a) codifying each interview line by line, and identifying all information into all the possible emergent categories; and b) applying the constant comparison method, which consists of simultaneous data coding and analysis in order to find similarities and diferences among the categories (Corbin & Strauss, 2015).

It is important to clarify that the codification process includes an inductive analysis and three specific steps: Open codification, axial open codification, and axial and selective codification. First, a detailed analysis of the interview transcripts through the open coding procedure was conducted; it led to the identification of social codes.

This process was followed by axial coding, which is used to explore relationships between categories and their specific subcategories. Once those categories were obtained we continued with the selective coding procedure, which involved inter-subject comparisons and identification of similarities and differences among the categories. The NVIVO 10 (http://www.qsrinternational.com) software for qualitative and mixed-methods analysis was used to analyze the information gathered in this study.

Trustworthiness

The methodology proposed by Grounded Theory includes a process to enhance the quality of the analysis and to increase the credibility of the information obtained in the study; this process is called trustworthiness (Cho & Lee, 2014). Researchers suggest different strategies to ensure trustworthiness; in this study we used thick description, tacit knowledge, multivocality triangulation, partiality and bias avoidance (Creswell, 2009; Tracy, 2010). First, during the data gathering process researchers used different questions to delve deeper into the information provided by participants on each of the topics included in the interview; additionally, a detailed analysis of each part of a participant’s interview resulted in thick descriptions of the concepts reflected in participants’ answers to those questions. Researchers considered the beliefs, values and personal experiences of each participant regarding the studied concepts during the information analysis process to ensure tacit knowledge. Emotions and thoughts generated in the participants by fatherhood, as well as the various ways in which they understand and exhibit their family involvement, were also taken into consideration during the analysis. These aspects also contributed to the multivocality strategy in the analysis process. Lastly, triangulation strategy was achieved through a constant discussion between the researchers regarding each phase of the analysis process, as well as the codes and categories identified in the interviews.

Results

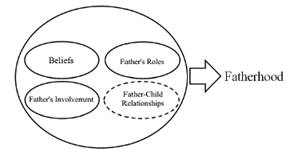

Researchers interested in the study of family dynamics have identified different aspects as the main determinants of parenting; those aspects are influenced by specific characteristics and relationships parents establish in the different contexts in which they are embedded. Parental beliefs are one of the factors that play an important role in the way parenting is reflected in the family (Belsky, & Volling, 1986; Parke, 2000). Three main categories were identified from the analysis of participant interviews: paternal beliefs, fathers’ roles and fathers’ involvement (see Figure 1). However, a fourth category - father-child relationships - emerged from the inductive analysis of the information, and participants highlighted it as one of the important dimensions of fatherhood.

Paternal beliefs about mother’s and father’s roles in the family

The category of paternal beliefs refers to the set of ideas fathers have regarding the features of motherhood and fatherhood in their social and cultural context. These characteristics seem to be influenced by particular aspects of the specific contexts in which they are embedded.

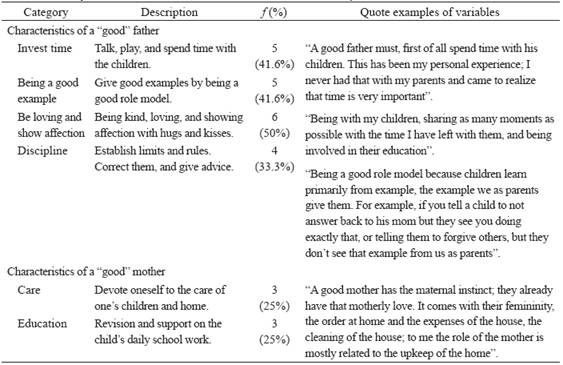

Table 2 summarizes the results included in this category. Fathers indicated that spending time with the family, and dedicating time to their children were crucial aspects of being a good parent. Some fathers also pointed out the importance of academic and personal education of children; the main way to contribute to this education was through good example or being role models. Having a good marital relationship was also indicated as important for good parenting.

Participants agreed on four primary characteristics that a good father must have. A primary role was given to the importance of being affectionate with the children and to show this affection with verbal and physical expressions (i.e. compliments, hugs, kisses). Being understanding, and establishing good communications with the children were central features of good fathering. Five fathers indicated that time is essential and “time lost cannot be retrieved”; spending time with the children is a way of showing them love and endearment. Four fathers identified the importance of a good academic education for the children (i.e. providing them with the best educational opportunities), and a good personal education in the family (i.e. setting limits and correcting them with dialog and reasons, when necessary). Five fathers highlighted the importance of being “good examples”, teaching them respect, endearment, and forgiveness. Concerning fathers’ beliefs about the characteristics of a “good mother”, the focus was put on tasks such as the care of the children as well as giving them academic support, and household upkeep.

Fathers’ perceptions of their parental roles in the family

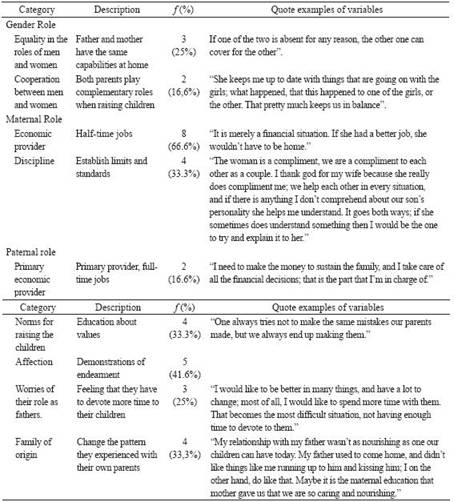

Results regarding the way fathers perceived their current role and the role of their wives in the family and with their children were coded into the category of Parental Roles (See Table 3). This category also included their view of the roles of their own parents in the family when they were growing up. Fathers referred to gender role differences in raising their children. Results showed that 3 fathers indicated that the capability of men and women to perform parental roles was similar; two fathers consider the roles of mothers and fathers as complementary, especially in relation to their children’s daily life activities.

Fathers indicated that mothers share the role of disciplining their children and establishing norms and limits with them. In most of the cases in this study mothers contribute economically to the family (66% of them work outside the home), although their income was lower than that of the fathers (part-time job). Fathers reported that their partners have a very important role in caring for their children, but they share some aspects of the fathers’ role that were previously associated mostly with men. Some fathers described themselves as the authority figure at home, but they said this role was shared with their wives. Within this authority role they emphasized the need of establishing norms, and agreements with their spouses in order to deal with problems or complicated situations at home. At the same time, they described themselves as affective fathers, emphasizing the importance of supporting their children and having a good communication with them. They also indicated they were involved in various aspects of their children’s lives, such as in their academic activities, supporting them with self-esteem issues, and teaching them to care for themselves. However, they pointed out as a negative aspect not having enough time to devote to their family and to share moments with their children; job demands were identified as the main reason for this limitation.

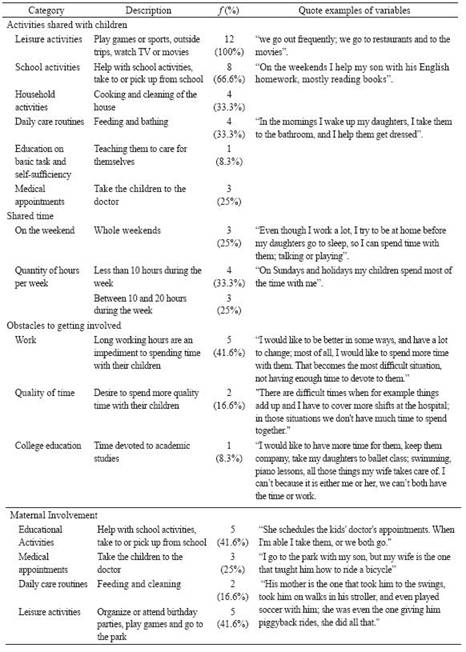

Fathers’ perceptions of their involvement in the family

Fathers indicated that they are usually involved in ludic activities with their children such as playing games or sports, doing outside activities, and watching TV (See Table 4). Most of them reported being involved in school activities such as helping with homework and taking the children to school. Fathers indicated they participated to a lesser extent in household activities, scheduling medical appointments or care activities with the children. Regarding spending time with their children, results showed that fathers tend to spend more time with their children during weekends and they argued that this is because of their job schedules. On average, they spend between 10 and 20 hours with their children during the week. Most of the fathers (66%) expressed that they would like to spend more time with their children and they recognized an important conflict between work and family as one of the main barriers to achieve that goal.

Some fathers pointed out that mothers showed higher involvement in rearing practices; for example, 5 fathers indicated that their spouses were in charge of most of the school activities; also, five fathers indicated that the mothers were the main responsible for children’s medical issues.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to explore Colombian fathers’ perceptions about parental roles in the family. Fathers were interviewed about their beliefs regarding fatherhood, the roles of fathers and mothers in the family, and fathers’ involvement in their children’s lives. Colombian’ society has experienced important social, cultural and economic transformations in the last decades; these changes have significantly influenced family dynamics and gender roles. These cultural changes have led to question whether the beliefs and perceptions of paternal and maternal roles have changed in respect to prior times, and at the same time, if these characteristics allow a new description of paternal involvement.

Four specific categories emerged from the participants’ interviews as the main aspects of fatherhood; these are paternal beliefs, fathers’ roles and fathers’ involvement, and father-child relationships. Specifically, findings showed that participants still have traditional beliefs about what should be a father and a mother, but at the same time, they are incorporating more innovative perceptions regarding their own and their wives’ participation in childcare.

Additionally, fathers believed their role in the family focuses on providing for basic needs and education. These perceptions are linked with the traditional male role within the family, in which the father represents the authority figure and economic provider. However, fathers also described themselves as affective fathers, who have a close relationship with their children. This relationship is expressed in emotional closeness and affective physical contact.

These results are consistent with some findings from previous studies that suggest that the father’s role within the family is showing some change, such as being more affective and involved in childcare, a task that was traditionally associated to the mother’s role in the family (Day & Lamb, 2004; Puyana & Mosquera, 2005).

Additionally, most fathers reported that both parents have similar parenting skills. That means that if one of them is absent, the other can assume his or her role. Many of the fathers perceive the role of mothers and fathers as complimentary. They perceive the care of their children as a shared task that concerns both fathers and mothers, and in which they can be emotionally involved. Likewise, they perceive gender roles in a more equitable manner, but still retain some gender stereotypes. It has been suggested that the perception of gender equity will allow an equitable distribution of childcare tasks within the family (Torres et al., 2008). Although the provider role still remains associated with a father’s responsibilities in Colombia, it can be said that the fathers in this study have a new and more “liberal” way to get involved with their children. Thus, the role of Colombian fathers in their families departs to some extent from the traditional pattern attributed to nuclear families. This departure places fathers in the category Puyana & Mosquera (2005) identified as “in transition”, which includes perceptions of more equitable parental roles within the family and a combination of features of other typologies of fatherhood proposed in the literature.

Fathers from the sample highlighted the importance of being available and to participate in their children’s activities, which corresponds to the main dimensions of a father’s involvement proposed by Lamb, Pleck, Charnov and Levine (1985). Specifically, they reported being involved in ludic (playing, sports, outside activities) and school activities (homework). Fathers also indicated that these activities took place mostly on weekends. Even though they shared activities with their children, they also identified some obstacles for their involvement with the family (i.e. time constrains due to job or educational requirements). This suggests a work-family conflict, where fathers perceive work as an impediment to spending quality time with their children.

Findings from this study contribute to broaden knowledge in the family research area by increasing information about fathers’ role in the family and with their children. A better understanding of fathers’ perceptions and involvement in the family would contribute to the development of family programs and policies that respond to the characteristics of Colombian families today. In Colombia, family structures and fathers’ participation in the family have changed over the last decades. Family policies in Colombia focus mainly on children and their mothers. There is also a need for programs to support fathers’ roles in the family.

The following are some of the limitations of the present study. First, this is an exploratory investigation whose main purpose was to approach, in a general way, fathers’ roles in the family in the Colombian context. Second, the sample size of the study was small; the results were not intended to be generalized. Third, there were some relevant contextual variables such as socio-economic status that can influence fathers’ role in the family, which were not considered in this study. Although the results provided some insights about the topic, further research is needed to examine specific questions regarding fathers’ roles and involvement in the family and with their children. For instance, the influence of different socio-demographic variables (SES, parents’ educational level, number of children in the family, family structure, etc.) on paternal roles and on fathers’ involvement, quality characteristics of father-child relationships, working conditions and their influence on fathers’ involvement, and the impact of social policies on family dynamics, specifically on the father’s role within the family