Introduction

The genus Corallorhiza Gagnebin (gr. κοράλλι, coral; ρίζα, root, referring to rhizomes that resemble coral structures) belongs to the subtribe Calypsoinae of the subfamily Epidendroideae (Chase et al. 2015). It is a genus of terrestrial orchids comprising 12 species (Freudenstein & Barret 2014, Pridgeon et al. 2005) restricted to North and Central America, except for C. trifida Châtel. (Freudenstein 1997, 1999, Magrath & Freudenstein 2002), which is circumboreal, and the recently described C. sinensis G.W.Hu & Q.F.Wang (Yang et al. 2021), an endemic taxon of China. Seven species are present in Mexico (Soto-Arenas et al. 2007), three of them with four infraspecies (Solano Gómez et al. 2020); all of them present in the Estado de México (Martínez de la Cruz et al. 2018, Szeszko 2011); five are Mexican endemics and C. bulbosa A.Rich. & Galeotti is restricted to Megaméxico 2 sensu Rzedowski (1991) (Espejo Serna 2012). Corallorhiza lack leaves and are mycoheterotrophic (Shefferson et al. 2010).

It is well known Orchidaceae has a very diverse array of pollination syndromes, the most common involves bees (melitophilia) and flies (myophilia) (Ackerman et al. 2023, Nidup et al. 2023, van der Cingel 2001); it is estimated that 15-30% of the whole family is pollinated by flies (Ackerman et al. 2023, van der Pijl & Dodson 1966). Nevertheless, for most orchid species pollinators are still unknown, especially for the more than 200 species of mycoheterotrophic orchids (Merckx et al. 2013), the only available studies are from Asia (Suetsugu 2013, Sugiura 1996, 2016, Zhou et al. 2012), Europe (Claessens & Kleynen 2014, 2018), and Oceania (Lehnebach et al. 2005). Pollinators for just three species of Corallorhiza have been identified (Claessens & Kleynen 2018, Freudenstein 1997, Kipping 1971).

Dressler (1981) suggested that Syrphidae flies pollinate Corallorhiza species, although the taxonomic identity of these visitors is known only for C. trifida (Kipping 1971); additionally, there are reports of selfpollination in some members of the genus. There exist few published data on floral visitors and pollinators for C. maculata (Raf.) Raf. var. mexicana (Lindl.) Freudenst., C. striata Lindl. var. striata, C. odontorhiza (Willd.) Poir. var. odontorhiza, C. odontorhiza var. pringlei (Greenm.) Freudenst., C. bentleyi Freudenst., and C. trifida (Argue 2012, Claessens & Kleynen 2018, Freudenstein 1997).

In Mexico, the genus Corallorhiza has been little studied, even on the reproductive biology of its species, so as a first approach to this subject, the purpose of this study was to document photographically and identify at the best possible taxonomic rank all the arthropods that rest or perch on Corallorhiza flowers for three species present in Monte Tláloc, Estado de México.

Material and methods

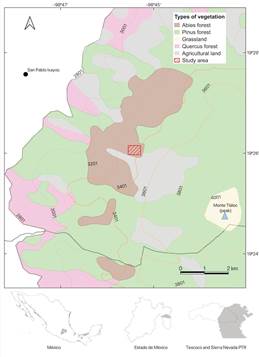

The study area is located on the west slopes of Monte Tláloc, municipality of Texcoco, Estado de México, it is part of the TransMexican Volcanic Belt and the Sierra Nevada (Priority Terrestrial Region) (Arriaga et al. 2000) (Fig. 1). The three Corallorhiza species habitat are coniferous forests of Abies religiosa (Kunth) Schltdl. & Cham., known locally as bosque de oyamel (Fig. 2). This vegetation type is present in ravines and lower slopes of mountains, between 3100 and 3500 m of elevation, with steep slopes greater than 40% (Sánchez-González & López-Mata 2003). The climate is humid-temperate, with an annual precipitation of 900 to 1000 mm, and an average annual temperature of 10 to 12°C (Ortiz Solorio & Cuanalo de la Cerda 1977). The type of soil is dark, deep, rich in organic matter, with medium texture (crumbs or loam), and pH values from 5.5 to 7.1 (Sánchez-González & López-Mata 2003).

Map by I. N. Gomez-Escamilla.

Figure 1 Study area, indicating vegetation types and territorial lines.

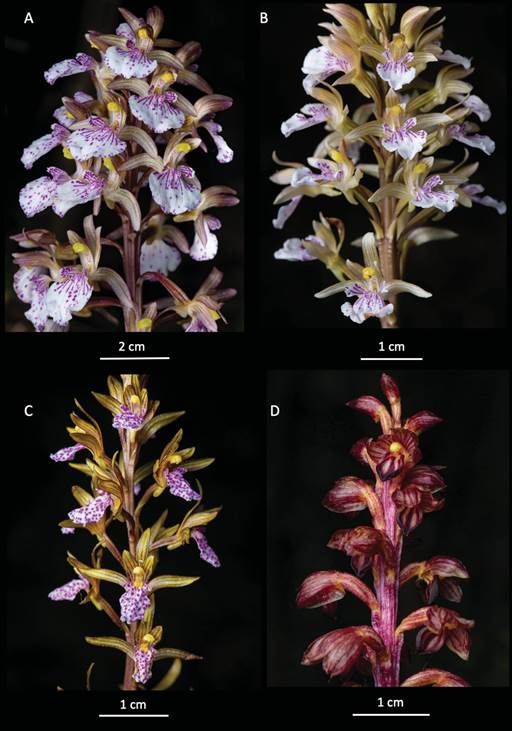

A. C. macrantha × C. maculata.

B. C. maculata. C. C. striata.

Photographs by B. Téllez-Baños.

Figure 2 Corallorhiza species growing sympatrically in the Abies forest in Monte Tláloc

A bibliographic revision of all literature regarding the genus Corallorhiza was undertaken (Freudenstein 1999, Lukasiewicz 1999). In addition, various digital repositories and databases were consulted to find the most complete background information on Corallorhiza's floral visitors. Moreover, to compare and identify the studied species (in situ), herbarium specimens of the genus were consulted and studied at the herbaria: CHAPA, MEXU, and UAMIZ (herbarium acronyms according to Index Herbariorum, Thiers continuously updated). The vouchers of this work are housed at UAMIZ. In the study area, Corallorhiza species are sympatric and in co-flowering, the plants generally are grouped in patches of up to eight individuals per species. To document the flower visitors, random walks were made between patches, when a visitor was detected, the observer approached with camera in hand to record the event. Observations were made from 8:00 am to 5:00 pm. during May 2018, 2019, and 2023. The photographs were taken with three digital cameras (Nikon model D800, Canon models Rebel T3 and SX50 HS), equipped with a macrophotography lens (Tokina atx-i 100mm, f/2.8 AF) and flashes with light diffusers. The species names for the insects were determined using identification guides (Triplehorn & Johnson 2005, Vockeroth & Thompson 1987).

To evaluate whether the species studied offer nectar as a reward, extractions were carried out on twelve flowers (three flowers per species, including the hybrid) using microcapillary tubes of 1 μl; for each sample the sugar concentration (°Brix) was recorded using a field refractometer (Mod. HRT32, range: 0-32% Brix, precision: 0.2%; A. Krüss Optronic, Germany). Extractions were carried out between 10 and 11 am.

Results

Literature and herbaria review.- Two species of Corallorhiza were previously reported from the studied area: C. macrantha Schltr. and C. striata var. involuta (Greenm.) Freudenst. (Sánchez-González et al. 2006), and we observed two more taxa: C. maculata var. mexicana (Lindl.) Freudenst. (I. N. Gomez-Escamilla & B. E. Tellez-Baños 222 (UAMIZ 85400)), and the hybrid C. macrantha × C. maculata (I. N. Gomez-Escamilla & B. E. Tellez-Baños 220 (UAMIZ 85398, UAMIZ 85397)) (Fig. 3), all growing sympatrically in the ravines Abies forest in Monte Tláloc.

Photographs by B. Téllez-Baños.

Scale bars are indicated.

Figure 3 Flowers of A. Corallorhiza macrantha. B. C. macrantha × C. maculata. C. C. maculata. D. C. striata.

All species of Corallorhiza grow on a moss substrate with abundant litter; their flowering period begins in late April ending in early June, while the fruiting season from July to December. The populations of C. macrantha were registered and collected for the first time in 1976, according with the specimens data (E. García Moya s. n. (CHAPA), Stephen D. Koch 76104 (CHAPA, MEXU)) and 45 years later, populations are still present in the area. The first specimen of C. striata var. involuta was collected in 1978 (José García P. 636 (MEXU), 637 (CHAPA, MEXU)).

Floral visitors.- Individuals belonging to five orders, eight families, four genera, and two species of insects were observed (Table 1, Fig. 4, 5, 6). The hybrid C. macrantha × C. maculata was visited by seven different insects, C. maculata var. mexicana by five, C. macrantha by three and C. striata var. involuta only by one. The total duration of observations for all species was 54 hours.

Nectar extractions.- For Corallorhiza macrantha a nectar volume of 0.8 μl, with a sugar concentration of 15°Brix was recorded while for C. maculata and the hybrid a volume of 0.6 and 0.4 μl respectively were obtained, which were insufficient to measure their sugar concentration. For C. striata no nectar was obtained.

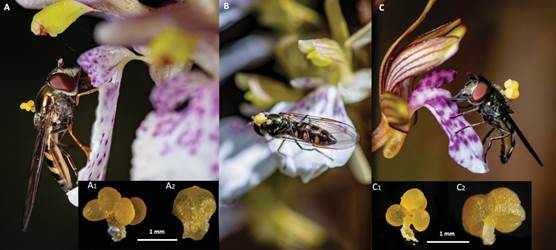

Potential pollinators.- Two species of syrphids were recorded transporting and depositing pollinia: Ocyptamus coeruleus (Williston 1891) on flowers of Corallorhiza macrantha, C. maculata and C. macrantha × C. maculata, and Platycheirus (Lepeletier & Serville 1828) on flowers of C. macrantha and C. macrantha × C. maculata (Table 1, Fig. 6). In addition, these insects made the highest number of visits (46) to the flowers (Table 1); most of them were recorded between 11:00 and 14:00 hrs.

Table 1 Comparative data of the species of Corallorhiza and their floral visitors in the study area.

| Species | Floral visitors | Number of visits | Carried pollinia | |||

| Order | Family | Genus | Species | |||

| Corallorhiza macrantha × Corallorhiza maculata | Coleoptera | Cantharidae | 1 | No | ||

| Curculionidae | 4 | No | ||||

| Hemiptera | Miridae | 1 | No | |||

| Hymenoptera | Apidae | Bombus | huntii | 8 | No | |

| Diptera | Syrphidae | Ocyptamus | coeruleus | 7 | No | |

| Platycheirus | sp. | 9 | Yes | |||

| Tachinidae | 4 | No | ||||

| Corallorhiza maculata var. mexicana | Araneae | Theridiidae | Theridion | sp. | 1 | No |

| Hemiptera | Cicadellidae | 2 | No | |||

| Diptera | Syrphidae | Ocyptamus | coeruleus | 15 | Yes | |

| Platycheirus | sp. | 4 | No | |||

| Tachinidae | 3 | No | ||||

| Corallorhiza macrantha | Diptera | Syrphidae | Ocyptamus | coeruleus | 4 | No |

| Platycheirus | sp. | 7 | Yes | |||

| Tachinidae | 5 | No | ||||

| Corallorhiza striata var. involuta | Coleoptera | Cantharidae | 1 | No | ||

Photographs by B. Téllez-Baños.

Figure 4 A. Bombus huntii (Apidae, Hymenoptera). B. Hymenoptera. C. Cantharidae (Coleoptera). D. Curculionidae (Coleoptera). E. Miridae (Hemiptera), visiting Corallorhiza macrantha × C. maculata. F. Cicadellidae (Hemiptera) visiting C. maculata.

Photographs by B. Téllez-Baños.

Figure 5 A. Platycheirus sp. visiting Corallorhiza macrantha × C. maculata B. Ocyptamus coeruleus (Syrphidae, Diptera) visiting and transporting pollinia from C. macrantha C. Platycheirus sp. visiting C. macrantha × C. maculata D. Ocyptamus coeruleus (Syrphidae, Diptera) visiting and transporting pollinia from C. maculata E. Tachinidae (Diptera), visiting C. macrantha × C. maculata. F. Theridion (Araneae: Theridiidae) visiting C. maculata.

Photographs by B. Téllez-Baños.

Scale bars are indicated.

Figure 6 A. Platycheirus sp. visiting Corallorhiza macrantha A1. Pollinia of C. macrantha A2. Anther of C. macrantha B. Platycheirus sp. visiting C. macrantha × C. maculata C. Ocyptamus coeruleus visiting C. maculata C1. Pollinia of C. maculata C2. Pollinia with anther of C. maculata.

The insects usually visit more than one flower of the same inflorescence and more than one individual in a floral patch. They fly in front of the flower for 2-8 seconds before landing on the labellum apex which is tilted downwards due to the weight of the insect, once it moves towards the base of the labellum in search of nectar guided by the purplish spots and lines, the labellum returns to its original position, pushing the syrphids against the column. With this mechanism, the thorax of the insect is positioned below the viscidium so that when the syrphid finishes drinking the nectar and move back to leave the flower, it makes contact with the viscidium and the pollinarium adheres, on some occasions with the anther, to the dorsal thorax (scutum) of the syrphid. Subsequently, when the insect visits another receptive flower, the pollinia carried on its thorax touch the stigmatic surface and adhere to it along with the insect’s body, so to free itself, the syrphid must struggle by holding and pushing the labellum with its legs, taking to 20 seconds to do so (Fig. 7).

A. Syrphid landing on the labellum with pollinia attached to its thorax.

B. Entering the flower in search of nectar.

C. Contact of the pollinaria with the stigma.

D. The pollinaria along with thorax of the insect remain attached to the stigma.

E-F. The insect struggles, holding the labellum and forcing it backwards with its legs to free itself from the pollinaria.

Figure 7 Photographic sequence showing the mechanism of pollinia deposition by Ocyptamus coeruleus (Williston 1891) in Corallorhiza macrantha flower.

Discussion

Suggested pollinators for the Calypsoinae subtribe are bumblebees, hover flies, empididae flies, mosquitoes, and bees (Valencia-Nieto et al. 2018). However, in this tribe the only genera with mycoheterotrophic members are Cremastra Lindl., Corallorhiza and Yoania Maxim. The information about their floral visitors and pollinators is very scarce (Claessens & Kleynen 2018, Freudenstein 1997, Kipping 1971, Sugiura 1996).

Bumblebees, unlike other insects, require a surface area to allow them to roost before starting to suck nectar from a flower, it has been reported that they pollinate flowers with large petals and lips (Blionis & Vokou 2001, Ortega-Olivencia et al. 2012). We found Bombus huntii (Greene 1860), as the floral visitor of Corallorhiza macrantha × C. maculata, a hybrid that has a large lip enough to support the landing of this insect, however the insect cannot fully access the flower due to its stout body, so by staying away from reproductive structures it is unlikely to remove or deposit a pollinia, limiting its pollinating role.

The syrphids were the only insects that made legitimate visits to the flowers of Corallorhiza (in terms of transporting and depositing pollinias), and they also made the highest number of visits. Therefore, we agree with Dressler (1981), that syrphids are the most likely pollinators of these orchids, in addition they may also be responsible for their hybridization. The evidence presented here, strongly suggest that Corallorhiza might be a group with a myophylic pollination syndrome. Previous works have documented the visit of a syrphid species in C. trifida (Claessens & Kleynen 2018), and for C. maculata var. maculata, the pollinators were identified as members of the genus Empis L. (Linnaeus 1758) (Diptera) (Kipping 1971). In other genera of mycoheterotrophic orchids such as Epipogium aphyllum Sw. (Jakubska-Busse et al. 2014) and Cremastra appendiculata (D. Don) Makino var. variabilis (Blume) I.D.Lund (Sugiura 1996) syrphids are also floral visitors.

The Hymenopteran Pimpla pedalis Cresson (1865) has been identified as a pollinator (Freudenstein 1997) of C. striata var. striata, while Freudenstein (1999) suggest the existence of autogamy for Corallorhiza striata var. involuta, hence we think that it is necessary to make more detailed observations in the populations of the orchid species to detect the presence of its pollinators. We would like to highlight the importance of the use of photography in this type of studies (Suetsugu & Hayamizu 2014, Suetsugu et al. 2017), since it allows the registration and taxonomic identification of the floral visitors, as well as the observation of the pollinia on their bodies.

Corallorhiza includes a group of orchids very vulnerable to environmental alterations to its habitat. The species require soils rich in organic matter and places with high humidity; therefore, it is important to preserve sites with the right conditions for the species thrive, including its dependency on its ectomycorrhizal fungi (Lee Taylor & Bruns 1999, Barrett et al. 2020). Currently, C. macrantha is cataloged as subject to special protection (Pr) in accordance with the NOM059-SEMARNAT-2010 (SEMARNAT 2019). It is a species is an orchid that cannot be cultivated, therefore in situ conservation is the only viable strategy to preserving it safely (Soto-Arenas & Solano-Gómez 2007).

Future studies should include more pollination observations and experimental manipulation of breeding systems, especially since 71 % of mycoheterotrophic orchids are likely autogamous (Ackerman et al. 2023); furthermore, of ca. 200 mycoheterotrophic species, only for 38 (17.67%) have studies been carried out regarding floral biology and/or floral visitors. It is important therefore to carry out studies in other mycoheterotrophic orchids to better understand the evolution of pollination strategies in this group of orchids that grow in temperate, temperate-tropical, and temperate subtropical areas.

uBio

uBio