Introduction

Commercial sea urchin aquaculture is a growing industry in different parts of the world. One of the main needs of an aquaculture company is to establish the optimal parameters of the recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) to maintain the farmed animals healthy, preventing disease outbreaks and overuse of antibiotics in order to have a successful business. The sea urchins are constantly exposed to high concentrations of bacteria, some of which are harmful, in addition to the microbiota derived via food. However, this microbiota also might be crucial for the host’s biocontrol, keeping it free of disease (Laport et al., 2018). Regular monitoring in a recirculation system can help identify changes in microbial composition and abundance that may indicate the presence of harmful bacteria or an imbalance in the ecosystem (de Bruijn et al., 2018; Hovanec & DeLong, 1996). Bacterial safety thresholds need to be established by determining a baseline of bacterial composition and abundance. If such threshold is reached, measures can be taken to prevent the outbreak of diseases, such as adjusting water quality parameters, increasing water change rates, or adjusting feed regimes (Dahle et al., 2023). Since several Vibrio bacterial species are known to infect numerous aquatic species, including fish, shrimp, and oysters, it is vital to monitor them in aquaculture (Dahle et al., 2023). Vibrio species are ubiquitous in marine environments and can be introduced into aquaculture systems through water, food, or other sources (Austin & Zhang, 2006; Thompson et al., 2004). The thresholds for Vibrio bacteria in different aquaculture species vary depending on the species being raised, the environmental conditions, and the management practices used in the system (Almeida et al., 2021; Rajeev et al., 2021; Dahle et al., 2023). In general, the thresholds for Vibrio bacteria in aquaculture systems are established based on the level of risk associated with the particular Vibrio species present, the environmental conditions, and the susceptibility of the species being raised (Arunkumar et al., 2020; Culot et al., 2021; Joshi et al., 2014; Prado et al., 2020). Until today, there has been no study focused on bacterial counts and Vibrio counts in sea urchin aquaculture to establish a threshold for management.

Regular monitoring can also help producers identify patterns in bacterial communities over time, and adjust management practices to maintain optimal bacterial composition and abundance (Dahle et al., 2023). Studies have shown that the composition and abundance of bacterial communities in recirculating aquaculture systems can vary over time, and can be influenced by a range of factors. These factors include water quality parameters, management practices, and the presence of aquatic species (Dahle et al., 2023). Studies have shown that the abundance of Vibrio bacteria in recirculating aquaculture systems can fluctuate over time, with peaks in abundance coinciding with increasing temperature or lowering pH. By maintaining a healthy and diverse bacterial community, it is possible to reduce the risk of disease outbreaks and minimize the need for antibiotics (Elston et al., 2008; Purgar et al., 2022). Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the bacterial counts in the seawater of A. dufresnii RAS to establish bacterial patterns, the main factors affecting those patterns, and safety thresholds.

Materials and methods

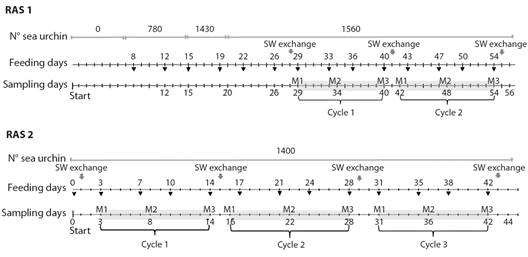

Aquaculture system design: Two RAS for commercial A. dufresnii sea urchin aquaculture were used in this study (Start Up ERISEA SA, a technology-based company located in Puerto Madryn, Chubut, Argentina). Each RAS consisted of one rectangular 3 000 l tank with a surface of 2 m2 and a depth of 70 cm, mechanical filters, one dark biofilter tank (1 000 l), a UV light, a chiller, and a water pump. Of the 3 000 l of seawater present in each RAS, 15 % was changed every 10-14 days. RAS were maintained at 15 °C and reared on an 8 h light/16 h dark cycle. RAS 1 was considered an immature system since it started without sea urchins and individuals were incorporated gradually from day 7 after launching the study (Fig. 1), while RAS 2 was a mature system, since it had a stable adult sea urchin population of 1 400 individuals (test diameter 35-40 mm) for at least 6 months prior to the study (Fig. 1). Animals were fed 400 mg of formulated feed twice a week, according to Rubilar et al. (2016). The farm’s staff performed daily visual inspections to assess the health of the sea urchins.

Fig. 1 Experimental setup of the sea urchin culture in recirculating aquaculture system. Light-grey shading shows each cycle. The different sampling moments are indicated: (M1) moment 1; (M1) moment 2 and (M3) moment 3.

Analyses of the RAS seawater microbiota: 500 ml water samples of each RAS were collected at three different points within each 3 000 l tank (at the ends and the middle) using sterile glass bottles and stored at 4 °C for 60 minutes until microbiological analyses were performed. The interval between one water exchange and the next was referred to as a “cycle”. Three moments were identified for each cycle: (M1) the moment after the exchange of seawater, (M2) six days after the seawater exchange, and (M3) the moment before the fresh exchange. Seawater samples were collected at those three times; when it coincided with the feeding day, the sample was taken before feeding.

The quantification of colony-forming units (CFU) was carried out by the serial dilution method, followed by plating on agar medium. Serial dilutions of such suspensions were prepared and plated on Tryptone Soya agar (TSA, Britania) to determine total aerobic heterotrophic populations, MRS agar for LAB, Violet Red Bile Dextrose Agar (VRB dextrose-agar, Biokar, France) for viable enterobacteriaceae, and Thiosulfate Citrate Bile Salt Sucrose agar (TCBS, Biokar, France) for genus Vibrio, using the spread plate method. All culture media were supplemented with 2.0 % (w/v) NaCl. Incubation was performed at 18 °C for 48-96 h. The counts were expressed as CFU ml-1 seawater.

Assessment of seawater quality parameters: Ammonium (NH4 + mg l-1), nitrites (NO2ˉ mg l-1), nitrates (NO3ˉ mg l-1) and pH were measured in collected seawater samples using a multiparameter equipment (Hanna® HI8323), temperature (T °C) and salinity (Vernier).

Data analysis: Test results were expressed as the mean ± SE. We performed a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test to compare median values of total bacteria and Vibrio spp. counts. Statistical analyses were carried out with the SPSS 25 package (Norusis, 1997).

As a first step, a graphical exploration, based on the scatter and residual plots of the data, was performed to understand the relationship between the bacterial counts, physicochemical parameters, as well as to explain the explanatory variables (RAS, seawater exchange, number of animals, and type of bacteria). To analyze the effect of seawater exchanges, number of animals, type of bacteria, and RAS system (mature and immature) on bacterial count, a Generalized Linear Model (GLM) was applied. Different replicates were included in the model analysis to evaluate method error and to analyze whether the replicates presented similar values. Different models, starting with a null model (a simpler model without any explanatory variable), were proposed, and their complexity resulted in a complex triple interaction model between the explanatory variables referred to as RAS, seawater exchange, number of animals, and type of bacteria. The best model was selected based on the Akaike criterion, considering the residual analysis, the explained variance (deviation), and the principle of parsimony or normality (Hurvich et al., 1998). All GLM analyses were performed with the free software R Studio version 3.5.1 (R Core Team, 2021).

Animals and welfare of animals: sea urchin aquaculture welfare protocol was applied during the entire experiment according to Crespi-Abril and Rubilar (2023).

Results

RAS seawater microbiota: Throughout the study, no enterobacteria or lactic acid bacteria were detected in any of the rearing seawater samples from both RAS. Instead, different counts of total bacteria and Vibrio spp. were recorded.

GLM analysis can be interpreted as that the number of animals had an important effect on the observed difference (DIF) in the count of total bacteria and Vibrio spp. in both RAS (Table 1). The analysis shows that the number of animals is important regardless of the interactive or additive effects; in fact, models 7 (RAS + N° Anim) and 8 (RAS * N° Anim) have the lowest AKAIKE values. In addition, model 4 presented slight differences in AKAIKE value, however, it is a simpler model, where only the number of individuals is the important factor for the bacterial count response. Considering the parsimony principle, model 4 is the best explanation for this analysis.

Table 1 Generalized Linear Model analysis for the bacterial count of the RAS1 and RAS2.

| Model for bacterial count | DIF | Akaike |

| 1. Null model | 1.82 | 3 586.35 |

| 2. RAS | 1.36 | 3 585.89 |

| 3. Bac | 2.75 | 3 587.28 |

| 4. N° Anim | 0.12 | 3 584.65 |

| 5. RAS + Bac | 2.27 | 3 586.80 |

| 6. RAS * Bac | 4.27 | 3 588.80 |

| 7. RAS + N° Anim | 0.00 | 3 584.53 |

| 8. RAS * N° Anim | 0.00 | 3 584.53 |

| 9. Bac + N° Anim | 1.03 | 3 585.55 |

| 10. Bac * N° Anim | 2.95 | 3 587.48 |

| 11. RAS + N° Anim + Bac | 0.88 | 3 585.41 |

| 12. RAS * N° Anim * Bac | 4.80 | 3 589.33 |

In bold, the model with the best fit according to the Akaike information criterion (AIC). Factors were RAS, number of animals (N° Anim), and type of bacteria (Bac).

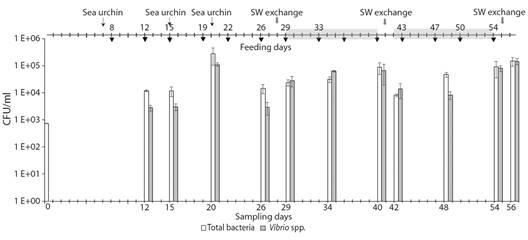

Immature RAS: In RAS 1, at the beginning of the sampled period without sea urchins, the total bacterial count in rearing seawater was 7.3 x 102 ± 2.1 x 101 CFU ml-1 of seawater, and no count was detected for Vibrio spp. (Fig. 2). GLM analyses can be interpreted as that the increase observed in the total bacteria count (1.2 x 104 ± 6.5 x 102 UFC ml-1) and the presence of Vibrio spp. (2.8 x 103 ± 6.6 x 102 UFC ml-1) was due to the incorporation of sea urchin into the system (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Table 2). During the experiment, the maximum counts of total bacteria and Vibrio spp. were 2.8 x 105± 1.7 x 105 and 1.45 x 105± 3.6 x 104 UFC ml-1, respectively (Fig. 2). On day 26, a decrease in the total bacteria and the counts of Vibrio spp. were observed without having performed a water exchange, which could be related to the decrease in organic matter since there was no feeding for 4 days.

Table 2 Generalized Linear Model analysis for the bacterial count of the RAS 1.

| Model for bacterial count | DIF | Akaike |

| 1. Null model | 2.893578 | 1 846.372 |

| 2. SW Exchange | 4.473507 | 1 847.952 |

| 3. Bac | 4.038361 | 1 847.517 |

| 4. N° Anim | 0.000000 | 1 843.478 |

| 5. SW Exchange + Bac | 5.786445 | 1 849.265 |

| 6. SW Exchange + N° Anim+ Bac | 1.889112 | 1 845.367 |

| 7. SW Exchange * N° Anim * Bac | 7.325407 | 1 850.804 |

In bold, the model with the best fit according to the Akaike information criterion (AIC). Factors were seawater exchange (SW Exchange), Type of bacteria (Bac) and number of animals (N° Anim).

Fig. 2 Total bacteria (white bars) and Vibrio spp. (grey bars) counts through time in the RAS 1. The data are presented as the mean of three repeated measures. Error bars indicate standard errors. The grey arrow indicates seawater exchange. Black arrow indicates the time of feeding and the thin arrow with the name “sea urchin” shows the date of the introduction of animals. Light-grey shading shows each cycle.

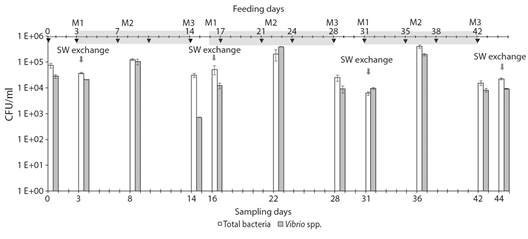

Mature RAS: RAS 2 had 1 400 sea urchins during the entire experiment. At the same period, the concentration of total bacteria and Vibrio spp. exhibited repetitive behavior over time. However, the bacterial counts within a seawater exchange cycle showed significant differences at all moments (M1, M2, and M3) of each cycle (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Bacterial counts through time in the RAS 2 seawater. Total bacteria (white bars) and Vibrio spp. (grey bars) counts. Data are presented as the mean of three repeated measures. Error bars indicate standard errors. The grey arrow indicates seawater exchange. Black Arrow indicates the date of feeding. Light-grey shading shows each cycle.

In the cycle 1 (C1), the total bacterial count for M1 (moment immediately after seawater change) was 3.73 x 104 ± 2.2 x 103 UFC ml-1 (Fig. 3, Table 3), for M2 the count was significantly higher at 1.26 x 105 ± 9.74 x 103 UFC ml-1 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3, Table 3), and at the end, immediately before the median of next water change (M3), it was lower (3.13 x 104 ± 6.06 x 103 UFC ml-1) respect to M2 ( KW p < 0.05) (Fig. 3, Table 3). Similarly, the Vibrio spp. counts were 2.1 x 104 ± 5.35 x 102 UFC ml-1 for M1, 1.04 x 105 ± 2.6 x 104 UFC ml-1 halfway through (M2), and 7.2 x 102 ± 1.15 x 101 UFC ml-1 for M3. These significant differences in the counts for the different moments of C1 were also observed for the following cycles (C2 and C3) (Fig. 3, Table 3). Throughout the evaluation period, the bacterial count showed a pattern that was repeated cycle by cycle. Feeding had a significant effect on the total bacteria and Vibrio count, this is evidenced in the count that was carried out the day after feeding (M2), since the count increased with respect to the previous one (M1) (Table 3). However, when sampling was performed on M3 at each cycle, the bacterial count decreased with respect to the previous count (M2).

Table 3 Bacterial count of the RAS 2 at different moments of the cycle.

| Cycle | Cycle time | ||

| M1 | M2 | M3 | |

| Total bacteria count CFU ml-1 | |||

| C1 | 3.73 x 104 ± 2.20 x 103a | 1.26 x 105 ± 9.74 x 103b | 3.13 x 104 ± 6.06 x 103a |

| C2 | 5.20 x 104 ± 1.92 x 104a | 2.03 x 105 ± 9.30 x 104b | 2.48 x 104 ± 6.40 x 103a |

| C3 | 6.20 x 103 ± 1.01 x 103a | 3.97 x 105 ± 5.24 x 104b | 1.54 x 104 ± 3.20 x 103a |

| Average value | 3.18 x 104 ± 8.74 x 103a | 2.42 x 105 ± 5.10 x 104b | 2.38 x 104 ± 3.50 x 103a |

| Vibrio spp. count CFU ml-1 | |||

| C1 | 2.10 x 104 ± 5.55 x 102b | 1.04 x 105 ± 2.60 x 104c | 7.20 x 102 ± 1.15 x 101a |

| C2 | 1.22 x 104 ± 3.10 x 103a | 3.93 x 105 ± 1.20 x 104b | 9.20 x 103 ± 2.75 x 103a |

| C3 | 9.63 x 104 ± 8.25 x 102a | 1.95 x 105 ± 2.30 x 104b | 8.23 x 103 ± 1.30 x 103a |

| Average value | 1.40 x 104 ± 1.96 x 103a | 2.31 x 105 ± 4.40 x 104b | 6.04 x 103 ± 1.60 x 103a |

The data are presented as the mean of three repeated measures. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between the mean values of the bacterial counts among the 3 moments of each cycle.

An average value for the total bacteria count (3.18 x 104 ± 8.74 x 103 UFC ml-1) and another for the Vibrio spp. count (1.40 x 104 ± 1.96 x 103 UFC ml-1) were obtained for M1, and were taken as basic reference values for this cycle moment. In the same way, average values were obtained for M2 (2.42 x 105 ± 5.1 x 104 and 2.31 x 105 ± 4.4 x 104 UFC ml-1, for total bacteria and Vibrio spp., respectively) and M3 (2.38 x 104 ± 3.5 x 103 and 6.04 x 103 ± 1.6 x 103 UFC ml-1; respectively).

GLM analysis showed that the null model presented a lower AKAIKE value, however, water exchange also presented a low value, indicating that it may not be the main factor but that it influences the bacterial count (Table 4).

Table 4 Generalized Linear Model analysis for bacterial count in the RAS 2.

| Model for bacterial count | DIF | Akaike |

| 1. Null model | 0.00 | 1 734.66 |

| 2. Bac | 1.63 | 1 736.29 |

| 3. SW Exchange | 0.86 | 1 735.52 |

| 4. SW Exchange + Bac | 2.48 | 1 737.15 |

| 5. SW Exchange * Bac | 2.60 | 1 737.26 |

In bold, the model with the best fit according to the Akaike information criterion (AIC). Factors Types of bacteria (Bac) and seawater exchange (SW Exchange).

Seawater quality parameters: Physicochemical parameters in the seawater affected the bacterial count in both RAS. GLM results showed that in RAS 1, the interaction between water exchange and ammonium and nitrite were the most important parameters that explained the bacterial count (Table 5). Instead, in RAS 2, water exchange along with nitrate were the most important parameters that explained the bacterial count; however, it is not clear if the effects are additive or if there is an interaction between them (Table 6).

Throughout the present study no changes in the behavior or general condition of the sea urchins were observed. There was no evidence of disease or mortality.

Discussion

This is the first study conducted on sea urchin aquaculture, measuring bacteria and their fluctuation in recirculation systems. Sea urchin aquaculture is a growing industry, and as a relatively new industry (Rubilar & Cardozo, 2021), it is important to establish effective and sustainable management plans from the beginning. In this regard, measuring bacteria and their fluctuation in recirculation systems can provide valuable information for the development of management plans that allow animal health and welfare while avoiding the use of chemical treatments and antibiotics in sea urchin production. While there are studies on disease treatments in sea urchins (Wang et al., 2013), these include formalin baths, benzalkonium chloride, and oxytetracycline; with the use of oxytetracycline being the most effective in controlling the disease. However, it is important to mention that the use of antibiotics and other chemical treatments in aquaculture can increase bacterial resistance and produce negative effects on the intestinal microbiota, which in turn can have negative consequences on their health and growth, the environment, and human health. Therefore, it is best to take preventive actions (Aly & Albutti., 2014; Chen et al., 2020; Vignesh et al. 2011; Watts et al., 2017).

According to our study, the presence of Vibrio spp. and other bacteria in water recirculation systems is related to the number of animals. In RAS 1, before the individuals were introduced, no bacteria of the genus Vibrio were detected in the culture water, this would indicate that the seawater treatment using UV light and filters (biological and physical ) that is carried out before introducing them to the RAS is effective and that the vibrio spp. are associated with sea urchins. This finding is in line with previous studies that have shown that the introduction of aquatic organisms in recirculation systems increased the presence of bacteria in the water (Blancheton et al., 2013; Rurangwa & Verdegem, 2015; Sharrer et al., 2005). Laport et al. (2018) isolated bacteria belonging to genus Vibrio from the gastrointestinal tracts of the sea urchins. In addition, Hakim et al. (2015) showed that the gut digesta and egested fecal pellets of sea urchins had a high abundance of class Gammaproteobacteria, of which Vibrio was found to be the primary genus. Furthermore, the production of biofilm by Vibrio spp. may actually be a survival tactic (Grimes, 2020; Wai et al., 1999) because cells can utilize nutrients absorbed into the biofilm matrix more effectively (Sampaio et al., 2022).

Although different culture conditions can yield varied bacterial counts (Haditomo et al., 2021), our findings demonstrate that the implemented water exchanges effectively maintained bacterial counts at levels that did not adversely impact the A. dufresnii sea urchin. These counts were comparable to those achieved in non-recirculating systems that require daily water exchanges. Importantly, our study has the advantage of being conducted without the use of antibiotics, distinguishing it from the research by Dang, Song et al. (2006) and Dang, Zhang et al. (2006).

The water exchanges in RAS 1 and 2 helped limit bacterial growth in the recirculation systems with established bacterial cycles. The nutrients that are available to bacteria could be diluted by these water exchanges, which would restrict their ability to proliferate. These results are consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated that water exchanges can influence the composition and abundance of the bacterial community in recirculation systems (Blancheton et al., 2013; Cardona et al., 2016; Eck et al., 2019).

Considering that the bacterial count increased the day following feeding compared to the prior counts, the feed clearly had an impact on the bacterial count. Additionally, the opposite result was observed when feeding was done four days prior to the count, which was reduced in comparison to the preceding counts. This is in accordance with preview works showing that the number of bacteria can be affected by a number of factors, such as the organic matter load of food (Alfiansah et al., 2018; García-Mendoza et al., 2019; Heenatigala & Fernando, 2016; Leonard et al., 2002; Qin et al., 2016; Vasile et al., 2017)

Sea urchins are known to be susceptible to poor water quality, especially when ammonia levels are high (Basuyaux & Mathieu, 1999; Lawrence et al., 2003; Rubilar & Crespi-Abril, 2017; Siikavuopio et al., 2004). Although some of the physicochemical parameters in this investigation were higher, it did not affect the welfare of the animals. In addition, it must be taken into account that they were commercial crops on a large scale and not small volumes like the aforementioned farming systems.

Despite fluctuations in the number of bacteria present in the recirculation systems, we did not find values indicating a significant risk of disease in the animal densities raised in our study. This result suggests that the bacterial count levels recorded in this study can be used as a threshold or safety limit for Arbacia dufresnii aquaculture. By monitoring bacteria levels within the ranges obtained in this study, it will be feasible to prevent the occurrence of diseases without resorting to antibiotics.

In conclusion, this study highlights the importance of measuring bacteria and their fluctuation in sea urchin aquaculture recirculation systems to establish effective and sustainable management plans. In addition, it would also allow designing strategies to maximize recirculation and plan the rate of water exchange. By monitoring bacteria levels and physicochemical parameters, it is possible to maintain the sea urchin culture in healthy conditions to prevent diseases without resorting to antibiotics and other chemical treatments. This approach can lead to a more responsible and environmentally friendly sea urchin aquaculture industry, and can also provide valuable insights for the development of aquaculture in other species.

Ethical statement: the authors declare that they all agree with this publication and made significant contributions; that there is no conflict of interest of any kind; and that we followed all pertinent ethical and legal procedures and requirements. All financial sources are fully and clearly stated in the acknowledgments section. A signed document has been filed in the journal archives.

uBio

uBio