Introduction

In coastal lagoons, the physical and chemical variables are influenced by tidal currents, upwellings, and seasonal cycles, as well as by the effect of topography, sediment, type of vegetation, river discharge, the effect of wind-induced mixing, and the system morphology itself (Kjerfve & Magill, 1989; Millán et al., 1982). This condition plays an essential role in modifying the population structure of phytoplankton, which groups the microscopic photosynthesizing organisms that live suspended in the photic zone. As we know, phytoplankton is a vital component of marine ecosystems since it produces approximately half of the global net primary production (Contreras & Warner, 2004).

Additionally, phytoplankton species are good bioindicators of hydro-climatic and anthropogenic changes, and some species can produce Harmful Algal Bloom (HAB) under certain environmental conditions. It causes deleterious impacts on organisms coexisting with them and human health, with negative consequences on the socio-economic activities of coastal communities (Cortés-Altamirano et al., 2019). In Veracruz, the HAB date from 1984 when a contingency occurred in the Alvarado, Tamiahua, Sontecomapan, and Port of Veracruz due to B. quinquecornis (=Peridinium quinquecorne), Ceratium furca var. hircus, Cyclotella spp., Chaetoceros holsaticus, Karenia brevis, Peridinium quinquecorne var. trispiniferum, Pyrodinium bahamense var. bahamense, Prorocentrum cordatum, Skeletonema spp., and T. furca (=Ceratium furca) (Aké-Castillo & Vázquez-Hurtado, 2008; Aké-Castillo & Vázquez-Hurtado, 2011; Gómez-Aguirre & Licea, 1998; Guerra-Martínez & Lara-Villa, 1996; Licea et al., 2004).

In the coastal lagoons of the Gulf of Mexico, various studies have been carried out focusing on listing and understanding the phytoplankton ecology. In Lagartos Lagoon, Quintana Roo, 67 taxa were registered. The highest abundance corresponded to Cyanobacteria, with about 80 % (Nava-Ruíz & Valadez, 2012). Furthermore, in Terminos Lagoon, Campeche, Muciño-Márquez et al. (2014) tested the composition and abundance of the phytoplankton and its relationship with some physical and chemical variables in the Pom-Atasta and Palizada del Este Lagoon systems, registering 263 and 348 taxa, with a predominance of diatoms and dinoflagellates, respectively. In different coastal lagoons of Veracruz, 14 genera of Cyanobacteria have been registered (Okolodkov & Blanco, 2011). The Bacillariophyta exhibit high species richness in Coscinodiscus, Chaetoceros, Nitzschia, Rhizosolenia, and Thalassiosira (Krayesky et al., 2009). In the meantime, 32 species of Chlorophyta have been registered in mixohaline coastal lagoons. Although they are not very abundant, the Euglenophyta indicates contamination. In Alvarado’s Lagoon, 18 taxa marine or mesohaline taxa were investigated in phytoplankton (Margalef, 1975). In the Tamiahua Lagoon, 39 Dinoflagellata have been recorded; it is known that Chlorophyta, Euglenophyta, and Chrysophyta are euryhaline common, while eutrophic estuaries are characterized by a high diversity of Cyanobacteria (Figueroa-Torres & Weiss-Martínez, 1999). Instead, in the Sontecomapan Lagoon, the morphology and distribution of the genus Skeletonema were analyzed (Aké-Castillo et al., 1995). For Mandinga Lagoon, Contreras-Espinosa et al. (1994) have recognized it as a eutrophic lagoon. Barón-Campis et al. (2005) reported the genera Lioloma, Navicula, Pleurosigma, Pseudo-nitzschia, and Thalassionema. Also, Salcedo-Garduño et al. (2019) studied the influence of physicochemical parameters on the distribution of 47 phytoplankton species. The Mandinga Lagoon is a vital ecosystem for its diversity and environmental services that benefit human use. However, knowledge about phytoplankton in this ecosystem must be improved to understand its real impact. Thus, the objective was to relate the phytoplankton diversity of Mandinga Lagoon with the physical and chemical conditions during the dry and wet seasons of 2017-2018, respectively.

Materials and methods

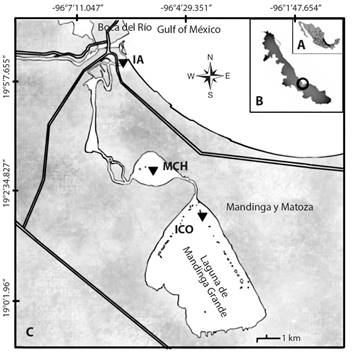

Study area: Mandinga’s Lagoon, Veracruz is located between (18º 59’-19º 05’ N & 96º 02’-96º 07’ W), has an approximate length of 20 km and is composed of six interconnected bodies of water: Estero del Conchal, Laguna Larga, Estero de Horcones, Laguna de Mandinga Chica or Laguna Redonda, Estero de Mandinga, and Laguna de Mandinga Grande (Fig. 1). It is a tropical environment with a temperature of 23.6-29 °C, the salinity of 18-31 PSU, and pH of 7.2. The dissolved oxygen concentration varies from 1.7 to 9.4 mg/L; NO3 and PO4 between 0.15- 0.6 mg/L and 0.082 to 0.153 mg/L, respectively. In addition to chlorophyll-a of 0.12 to 0.17 mg/L (Salcedo-Garduño et al., 2016). Concerning rainfall, the highest annual average was in September (2018) with 270 mm, and the lowest was in April (2017) with 17 mm during the dry season (Weather Spark, s.f.). Also, in the lagoon, there are various fishing resources of great economic value; it is one of the primary Crassostrea virginica oyster producers in the Gulf of Mexico, as well as Crystal shrimp (Penaeus sp.) and crab (Callinectes similis). Such products constitute an essential income source for the surrounding settlements (Lango et al., 2013).

Fig. 1 A. Map of Mexico, B. Veracruz state, C. Study area, location of the sampling sites in the Mandinga Lagoon: IA, Isla del Amor; MCH, Mandinga Chica, and ICO, Isla Conchas.

Collection of biological material: The samples of biological material were collected in the wet (September 2017 and 2018) and dry (March 2018) seasons in three stations: Isla Conchas (ICO), Mandinga Chica (MCH), and Isla del Amor (IA), respectively (Fig. 1). At each station, horizontal trawling was performed for five minutes using a net with a mesh size of 20 µm. This material was divided into two equal fractions: the first was kept in vivo at a temperature of 4 °C, and the other was preserved with formaldehyde at a final concentration of 4 % with sodium borate (Tomas, 1997). Additionally, two 500 ml samples were taken in the first 20 cm of the water column; one of them was preserved with Lugol acetate for quantification by the Utermöhl method (Edler & Elbrächter, 2010), and the second was used to determine the limnological variables (APHA et al., 2005).

Limnological variables: In each study station, registrations were made in situ for the following variables. A Brannan thermometer was used for water temperature; pH was measured using a Cole Parmer potentiometer and Digi-sense model; the transparency and depth were measured using Secchi Disc and Speedtech USA, respectively. Dissolved oxygen concentration and total alkalinity were measured using the Winkler technique and methyl orange titration. The salinity and electrical conductivity were recorded using an Atago PAL-03S Japan refractometer and a Hanna HI98312. Finally, a Hach spectrophotometer model DR2800 was used, and the test package for orthophosphates using the molybdovanadate method 8114 and nitrates cadmium-reduction method 8153 (APHA et al., 2005). Chlorophyll-a quantification (mg/m³): A 50 ml water sample was collected using the Strickland & Parsons (1972) technique.

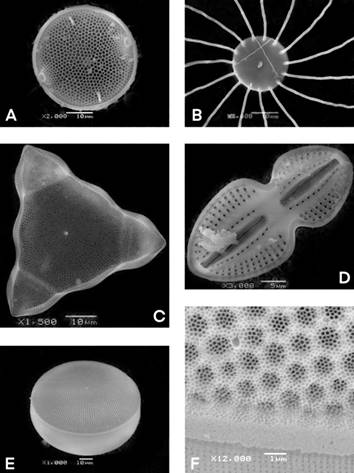

Processing of biological material: The phytoplankton samples were analyzed using a Leica light microscope. In order to study the thecal plates of dinoflagellates, 0.2 % trypan blue (Taylor, 1978). For clean diatoms, the oxidative method was used Hasle & Fryxell (1970) and was subsequently observed with a scanning electron microscope (SEM JEOL model JSM6380LV) according to Ferrario et al. (1995). The works of Tomas (1997), Komárek & Anagnostidis (1999), Komárek & Anagnostidis (2002), and Okolodkov (2008) were used for taxonomic determination based on the classification indicated in the algae database (Guiry & Guiry, 2024). Finally, the new registrations for the Gulf of Mexico coasts were based on Krayesky et al. (2009), León-Tejera et al. (2009), Steidinger et al. (2009), and Salcedo-Garduño et al. (2019). The material was placed in the herbarium IZTA 1910-1914 (Thiers, 2020).

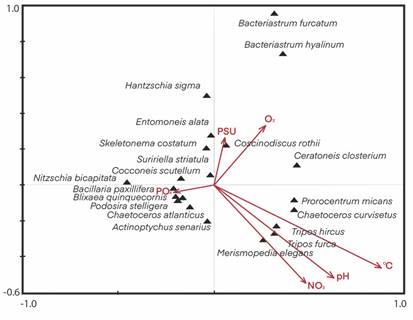

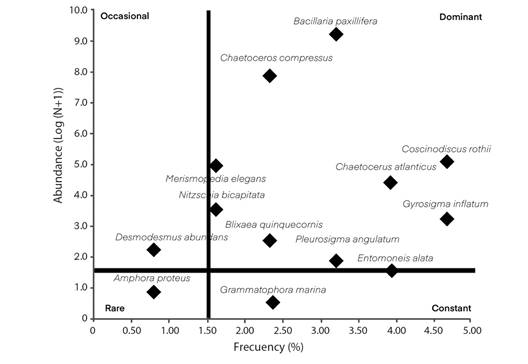

Statistical analysis: The Shannon-Wiener Diversity Index and the Olmstead-Tukey analysis were also carried out (Sokal & Rohlf, 1981). Also, to know the relationship between the dominant and constant species with limnological variables, a CCA was performed using the Monte Carlo permutation test (9999 permutations, α = 0.05) in the CANOCO software for Windows 4.5 (Ter-Braak & Smilauer, 2009).

Results

Physical, chemical, nutrient, and chlorophyll-a variable: Water temperature ranged from 21 to 29 °C and salinity from 0 to 32 PSU. Water pH was slightly alkaline with 8.0-8.8, and a well-oxygenated environment valued at 6.0-12 mg L-1. Chlorophyll-a, transparency and depth were higher in the wet season (Table 1).

Table 1 Values of environmental variables registered during dry and wet seasons at the sampled sites in the Mandinga Lagoon.

| Sites of sampling | Station 1-ICO | Station 2-MCH | Station 3-IA | Interval | |||

| Seasons | Dry | Wet | Dry | Wet | Dry | Wet | |

| Environmental variables | |||||||

| 1. Water temperature (°C) | 29 | 22 | 27 | 21 | 28 | 21 | 21-29 |

| 2. Ionization potential (pH) | 8.4 | 8.1 | 8.8 | 8.0 | 8.5 | 8.1 | 8.0-8.8 |

| 3. Dissolved oxigen (mg/L) | 6.8 | 9.2 | 8.4 | 12 | 6 | 3.6 | 6-12 |

| 4. Alcalinity (mg/L CaCO3) | 89 | 220 | 20 | 230 | 80 | 225 | 20-230 |

| 5. Conductivity (µS/cm) | 31 | 36 | 40 | 37 | 20 | 45 | 31-45 |

| 6. Salinity (PSU) | 0 | 0 | 32 | 32 | 25 | 25 | 0-32 |

| 7. Nitrate (mg/L) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0-1 |

| 8. Phosphate (mg/L) | 1 | 2.2 | 1 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0-2.2 |

| 9. Chlorophyll-a (mg/m³) | 3.2 | 11 | 3 | 9.0 | 3 | 8.1 | 3-11 |

| 10. Transparency (cm) | 43 | 80 | 28 | 100 | 60 | 200 | 28-200 |

| 11. Depth (cm) | 52 | 98 | 28 | 126 | 100 | 420 | 28-420 |

Station1-ICO: Station 1-Isla Conchas; Station 2-MCH: Station 2-Mandinga Chica and Station 3-IA: Station 3-Isla del Amor.

Phytoplankton of composition: Table 2 shows the specific richness of phytoplankton in the study area exhibited 40 species of euryhaline and 96 of stenohaline. The distribution was different in each of the stations: 53 species were recorded at ICO; in the MCH, there were 64 species, and finally, in IA, 79 species were recognized.

Table 2 List of Taxa registered at the sampled sites in the Mandinga Lagoon.

| Sites of sampling | S1-ICO | S2-MCH | S3-IA |

| Salinity (PSU) mean values | 0 PSU | 32 PSU | 25 PSU |

| Cyanobacteria | |||

| Anabaena sp. | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Johannespbatistia sp. | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Leptolyngbya gracilis (Lindstedt)Anagnostidis & Komárek | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Lyngbya sp. | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| *Merismopedia elegans A. Braun ex Kützing | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Merismopedia insignis Skorbatow (Shkorbatow) | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Microcystis wesenbergii (Komárek) Komárek ex Komárek | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| *Spirulina robusta H. Welsh | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Chlorophyta | |||

| Desmodesmus abundans (Kirchmer) E. H. Hegewald | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Monactinus simplex (Meyen) Corda | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Pseudopediastrum boryanum (Turpin) E. Hegewald | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Euglenophyta | |||

| Lepocinclis acus (O. F. Müller) B. Marin & Melkonian | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Heterokontophyta (Bacillariophytina) | |||

| Actinocyclus circellus T. P. Watkins | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| *Actinoptychus senarius (Ehrenberg) Ehrenberg | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Actinoptychus splendens (Shadbolt) Ralfs | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Alveus marinus (Grunow) Kaczmarska & Fryxell | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Amphora proteus W. Gregory | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| *Asterionellopsis glacialis (Castracane) Round | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Aulacoseira granulata (Ehrenberg) Simonsen | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Azpeitia nodulifera (A. W. F. Schmidt) G. A. Fryxell & P. A. Sims | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| *Bacillaria paxillifera (O. F. Müller) T. Marsson | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Bacteriastrum elongatum Cleve | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Bacteriastrum furcatum Shadbolt | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Bacteriastrum hyalinum Lauder | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sites of sampling | S1-ICO | S2-MCH | S3-IA |

| Salinity (PSU) mean values | 0 PSU | 32 PSU | 25 PSU |

| *Bellerochea malleus (Brightwell) Van Heurck | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Biddulphia biddulphiana (J. E. Smith) Boyer | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Biddulphia tridens (Ehrenberg) Ehrenberg | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| *Caloneis permagna (Bailey) Cleve | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Campylodiscus braziliensis J. M. Deby | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Cerataulus smithii Ralfs | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Ceratoneis closterium Ehrenberg | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Chaetoceros affinis Lauder | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Chaetoceros brevis F. Schütt | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Chaetoceros atlanticus Cleve | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| *Chaetoceros compressus Lauder | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Chaetoceros curvisetus Cleve | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Chaetoceros decipiens Cleve | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Chaetoceros lorenzianus Grunow | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Chaetoceros messanensis Castracane | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Chaetoceros protuberans Lauder | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Chaetoceros radicans F. Schütt | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Chaetoceros rostratus Ralfs | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| *Cocconeis scutellum Ehrenberg | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Coscinodiscus granii L. F. Gough | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| *Coscinodiscus radiatus Ehrenberg | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Coscinodiscus rothii (Ehrenberg) Grunow | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Coscinodiscus wailesii Gran & Angst | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| *Cyclotella stylorum Brightwell | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| *Cymbella tumida (Brébisson) Van Heurck | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Detonula pumila (Castracane) Gran | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| *Diploneis bombus (Ehrenberg) Ehrenberg | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Diploneis splendida Cleve | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ditylum brightwellii (T. West) Grunow | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sites of sampling | S1-ICO | S2-MCH | S3-IA |

| Salinity (PSU) mean values | 0 PSU | 32 PSU | 25 PSU |

| *Entomoneis alata (Ehrenberg) Ehrenberg | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Fragilaria sp. | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| *Grammatophora sp. | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Grammatophora marina (Lyngbye) Kützing | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| *Guinardia delicatula (Cleve) Hasle | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Guinardia flaccida (Castracane) H. Peragallo | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| *Gyrosigma inflatum Ricard | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| *Hantzschia pseudomarina Husted | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Hantzschia sigma Hustedt | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Haslea wawrikae (Husedt) Simonsen | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Helicotheca tamesis (Shrubsole) M. Ricard | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Hobaniella longicruris (Greville) P. A. Sims & D. M. Williams | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| *Hemiaulus sinensis Greville | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Lauderia annulata Cleve | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| *Licmophora sp. | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| *Lithodesmium undulatum Ehrenberg | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Lyrella lyra (Ehrenberg) Karajeva | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Navicula sp. | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Navicula gastrum (Ehrenberg) Kützing | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Navicula lanceolata Ehrenberg | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Navicula pennata A. W. F. Schmidt | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Neidium sp. | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| *Nitzschia bicapitata Cleve | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Nitzschia braarudii Hasle | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Nitzschia granulata Grunow | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| *Nitzschia longissima (Brébisson ex Kützing) Grunow | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Nitzschia sicula (Castracane) Hustedt | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| *Nitzschia sigma (Kützing) W. Smith | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Nitzschia spathulata Brébisson ex W. Smith | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sites of sampling | S1-ICO | S2-MCH | S3-IA |

| Salinity (PSU) mean values | 0 PSU | 32 PSU | 25 PSU |

| Odontella aurita (Lyngbye) C. Agardh | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Palmerina hardmaniana (Greville) G. R. Hasle | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Petrodictyon gemma (Ehrenberg) D. G. Mann | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Petroneis granulata D. G. Mann | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| *Pleurosigma angulatum (J. T. Quekett) W. Smith | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| *Pleurosigma diversestriatum F. Meister | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| *Podosira stelligera (Bailey) A. Mann | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Proboscia alata (Brightwell) Sundström | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Pseudo-nitzschia cf. pungens (Grunow ex Cleve) Hasle | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Pseudo-nitzschia cf. pseudodelicatissima (Hasle) Hasle | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Rhizosolenia setigera Brightwell | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Rhopalodia sp. | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Skeletonema sp. | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Skeletonema costatum (Greville) Cleve | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Stephanopyxis sp. | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| *Surirella recedens A.W. F. Schmidt | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| *Surirella striatula Turpin | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| *Thalassionema bacillare (Heiden) Kolbe | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Thalassionema nitzschioides (Grunow) Mereschkowsky | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Thalassiosira lineoides Herzig & Fryxell | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Thalassiosira delicatula Ostenfel | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Thalassiothrix longissima Cleve & Grunow | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Trieres mobiliensis (Bailey) Ashworth & E.C. Theriot | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Dinoflagellata | |||

| Azadinium cf. spinosum Elbrächter & Tillmann | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| *Blixaea quinquecornis (T. H. Abé) Gottschling | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Cochlodinium sp. | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Cochlodinium sp. 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| *Dinophysis fortii Pavillard | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Sites of sampling | S1-ICO | S2-MCH | S3-IA |

| Salinity (PSU) mean values | 0 PSU | 32 PSU | 25 PSU |

| Diplopsalis sp. | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Gonyaulax polygramma F. Stein | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Gonyaulax spinifera (Claparède & Lachmann) Diesing | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Gonyaulax spirale Diesing | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Gonyaulax sp. | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Gyrodinium sp. | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| *Karenia mikimotoi (Miyake & Kominami ex Oda) Gert Hansen & Moestrup | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Lingulodinium sp. | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Peridinium quinquecorne var. trispiniferum Aké-Castillo & G. Vázquez | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Protoperidinium abei (Paulsen) Balech | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| *Protoperidinium conicum (Gran) Balech | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Protoperidium oceanicum (Vanhöffen) Balech | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Protoperidium oviforme (P.J.L. Dangeard) Balech | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Protoperidium ovum (J. Schiller) Balech | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Protoperidinum pellucidum Bergh | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Protoperidium pyriforme (Paulsen) Balech | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Protoperidinium quarnerense (B. Schröder) Balech | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Protoperidium subinerme (Paulsen) A. R. Loeblich III | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| *Prorocentrum gracile F. Schütt | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| *Prorocentrum micans Eh | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| *Tripos furca (Ehrenberg) F. Gómez | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tripos furca var. eugrammus (Ehrenberg) F. Gómez | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| *Tripos hircus (Schröder) F. Gómez | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Scrippsiella trochoidea (F. Stein) A. R. Loeblich III | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Scrippsiella spinifera G. Honsell & M. Cabrini | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Warnowia sp. | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| ∑ | 53 | 64 | 79 |

S1-ICO: Station 1-Isla Conchas; S2-MCH: Station 2-Mandinga Chica, and S3-IA: Station 3-Isla del Amor. Practical Salinity Unit (PSU): mean values, 1: Presence and 0: Absence. *Euryhaline taxa, and names of species in bold are new registers in the area study

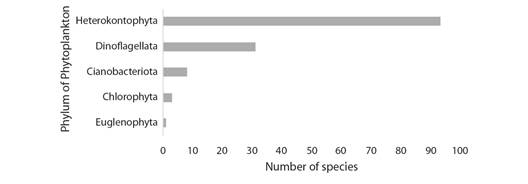

Phytoplankton composition: A total of 136 taxa distributed in five Phylum were registered, 68.4 % (93) to Heterokontophyta (Bacillariophytina), 22.8 % (31) to Dinoflagellata, 5.9 % (8) of which correspond to Cyanobacteria, 2.2 %, (3) to Chlorophyta, and 0.7 % (1) to Euglenophyta (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3).

Fig. 2 Number of species by Phylum Heterokontophyta (Bacillariophytina), Dinoflagellata, Cyanobacteriota, Chlorophyta and Euglenophyta registered in the Mandinga Lagoon.

Fig. 3 SEM A. Cerataulus smithii , external view showing ocelli and spines. B. Bacteriastrum hyalinum , Internal valve view showing terminal setae. C. Lithodesmium undulatum , Valval view triangular, showing the central spine, each side having a median inflation. D. Diploneis bombus , inside view cell showing rafe and striae. E. Azpeitia nodulifera , valve face with radial rows of areolate. F. A. nodulifera, areolae occluded by criba and external aperture of rimoportula (arrow). Scale bars F = 1 µm, D = 5 µm; A, B, C, E = 10 µm.

Abundance phytoplankton: Heterokontophyta species rank eight places out of the first 10 in abundance: B. paxillifera, C. compressus, C. rothii, C. atlanticus, N. bicapitata, S. costatum, G. inflatum, and N. pennata. To complete the list one Cyanobacteria: M. elegans, and one Dinoflagellata: B. quinquecornis. Regarding the stations and seasons studied, the highest abundance was 307 x 103 cells/ml during the dry season in the ICO station in 2018; instead, the lowest abundance was observed in the MCH station during the wet season in 2018 with 76 x 103 cells/ml (Table 3).

Table 3 Dominant species registered both in wet and dry seasons in the Mandinga Lagoon (2017-2018).

| Taxa | ICOW17 | MCHW17 | ICOD18 | MCHD18 | IAD18 | ICOW18 | MCHW18 | IAW18 | Total |

| Bacillaria paxillifera | 0 | 41 | 165 | 0 | 10 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 238 |

| Chaetoceros compressus | 0 | 0 | 42 | 19 | 147 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 208 |

| Coscinodiscus rothii | 0 | 0 | 29 | 7 | 20 | 24 | 22 | 29 | 132 |

| Chaetoceros atlanticus | 0 | 0 | 30 | 17 | 23 | 20 | 37 | 0 | 127 |

| Merismopedia elegans | 10 | 0 | 0 | 98 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 108 |

| Nitzschia bicapitata | 72 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Skeletonema costatum | 0 | 39 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 49 | 99 |

| Gyrosigma inflatum | 0 | 24 | 6 | 15 | 5 | 18 | 17 | 0 | 85 |

| Blixaea quinquecornis | 54 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 80 |

| Navicula pennata | 53 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 69 |

| ∑ | 188 | 132 | 307 | 163 | 214 | 83 | 76 | 79 |

Data expressed in 103 cells/ml. ICOW17: Isla Conchas Wet 2017; MCHW17: Mandinga Chica Wet 2017; ICOD18: Isla Conchas Dry 2018; MCHD18: Mandinga Chica Dry 2018; IA18: Isla del Amor Dry 2018; ICOW: Isla Conchas Wet/Rainfall 2018; MCHW: Mandinga Chica Wet 2018 and IAW18: Isla del Amor Wet 2018.

Diversity Index and species dominance: The Shannon index showed a maximum value of 1.31 bits/ind. at ICO in the dry season (2018), the minimum value was 0.70 bits/ind. in IA during the wet season (2018).

According to the Olmstead-Tukey diagram, the dominant groups were Heterokontophyta and Dinoflagellata; 48 % of the phycoflora were rare species, followed by 29 % dominants, 20 % constant, and 3 % occasional-some examples of the dominant: B. paxillifera, C. compressus, C. rothii, and C. atlanticus. In contrast, the constant was G. marina. Moreover, the occasional was D. abundans. Lastly, A. proteus was rare (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Olmstead-Tukey diagram showing the importance of species: dominant, occasional, constant and rare from Mandinga Lagoon.

Analysis of phytoplankton and limnological variables: Our results show that quadrant I was related to salinity and dissolved oxygen with C. rothii and C. closterium (Heterokontophyta). The quadrant III was associated with phosphates, whose taxa were represented by B. paxillifera, C. atlanticus, P. stelligera, A. senarius, and B. quinquecornis (Dinoflagellata). The quadrant IV was related to pH, nitrates and temperature; the highest water temperature values, 27-29 °C, with T. furca, T. hircus, P. micans, C. curvisetus, and M. elegans (Cyanobacteria). At the same time, the species of quadrant II did not show a relation with limnological variables, e.g. S. costatum, C. scutellum, and N. bicapitata (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Limnological variables: The variables showed the following based on the data obtained during 2017-2018 (Table 1). The surface temperature of the water ranged from 27-29 °C in the dry season, while in the wet season, it ranged from 21-22 °C. For this reason, during the dry season, water temperature falls into the classification of tropical environments, according to Lara-Domínguez et al. (2011) for several lagoons in Veracruz.

In contrast, data from 1975 by Arreguín-Sánchez (1982) indicated temperatures from 16 to 32 °C, with the lowest temperatures during January and February. Also, Salcedo-Garduño et al. (2016) and Salcedo-Garduño et al. (2019) showed temperature registrations from 20.8 to 29.9 °C, as well as temperatures from 28 to 31 °C in the dry season and rains in the same lagoon by González-Vázquez et al. (2019). There also similar temperature registrations from 23 to 33 °C for the Alvarado Lagoon (Rivera-Guzmán et al., 2014) and from 22.8 to 26.2 °C in Sontecomapan (Muciño-Márquez et al., 2012).

For the study area, the average pH value was 8.3 ± 0.26, while the minimum was 8 in the wet season; these are slightly basic chemical conditions due to the influence of seawater intrusion into the coastal lagoons. For other habitats of Veracruz, such as the Tapamachoco Lagoon, Contreras & Warner (2004) indicate a pH of 8.0-8.2. While for the winters, the registered pH was 7.1-7.8, which can be explained by the degradation of organic matter or by removing sediment due to the effects of the current, causing remineralization (López-Ortega et al., 2012). Also, for the La Mancha Lagoon, the pH in the dry season is 7.8 and rainy is 8.1 respectively (Rivera-Guzmán et al., 2014). At Sotecomapan Lagoon value was near neutral, 7.3-7.8 (Muciño-Márquez et al., 2012).

The salinity in this study ranged between 0 to 32 PSU, which is why it is considered an euryhaline environment. Therefore, it is not confirmed as polyhaline (10-20 PSU) as indicated by Lara-Domínguez et al. (2011), Salcedo-Garduño et al. (2016) and Salcedo-Garduño et al. (2019), whose values ranged between 21-31 PSU. Likewise, Arreguín-Sánchez (1982) and González-Vázquez et al. (2019) recorded in Mandinga Lagoon values of 0.5 to 33 PSU during dry and wet seasons. These data should not be forgotten that they can be very dynamic due to the change of tides, such as that recorded in the Sontecomapan Lagoon, Veracruz, during the nyctemeral cycle in the rainy season where the change of tides explains the values 3 to 6 PSU in the morning while 30.5 PSU later at 5:00 P.M. (Muciño-Márquez et al., 2012).

The values for dissolved oxygen ranged from 6.7 to 9.3 mg/L, which is why this environment is recognized as well-oxygenated (Salcedo-Garduño et al., 2016). These data confirm what was stated by Lara-Domínguez et al. (2011) for the coastal lagoons of the Gulf of Mexico, where the efficient pattern of water circulation and renewal, as well as an intense activity of primary producers, allow a dynamic of this limnological condition in a well-oxygenated coastal environment.

Our nitrate and phosphate values for Mandinga Lagoon ranged from 0 to 1 mg/L and 0 to 2.2 mg/L, respectively. The highest values were initially recorded in the wet season, explained by the nutrient incorporation and dragging into the basin. Instead, Salcedo-Garduño et al. (2016) indicated concentrations of nitrates from 0.15 to 0.6 mg/L and phosphates from 0.08 to 0.15 mg/L from 2011 to 2012. For its part, Contreras-Espinosa et al. (1994) indicated that nitrates from 33 Mexican coastal lagoons ranged from 0.049 to 0.070 mg/L and supported the idea that these nutrients are generally higher in the wet season. These values do not correspond to the nutrient ranges found in the coastal lagoons of Veracruz, where the number of nitrates ranged from 0.05 to 0.14 mg/L and the number of phosphates from 0 to 0.15 mg/L (Lara-Domínguez et al., 2011). Vázquez et al. (2007) mainly report nitrate amounts of 1.6, 1.1, and 1.4 mg/L and phosphorus amounts of 0.9, 1.5, and 1.8 mg/L for eutrophic lakes Chalchoapan, Verde, and Mogo, Veracruz, respectively.

During the study period in Mandinga Lagoon, the chlorophyll-a levels ranged from 3 to 11 mg/m3, implying low primary productivity in the system. Contreras-Espinosa et al. (1994) and Lara-Domínguez et al. (2011) recorded values from 30 to 40 mg/m³ during the same seasons, which indicates that the registration was higher at another season. Also, Salcedo-Garduño et al. (2019) indicated values from 8 to 15 mg/m3 in the same climatic seasons. On the other hand, in Tampamachoco Lagoon, values from 10 to 20 mg/m³ were recorded in 1980; a decade later, the records were 20 to 30 mg/m³, which indicates that there are changes in limnological dynamics over time, associated with the abundance of photosynthetic organisms that, in turn, are responsible for the dissolved oxygen concentrations reached in the water column. During the wet season, the maximum concentration of chlorophyll-a, Secchi transparency, and lower phytoplankton abundance was observed compared to the dry season (Table 1). These differences in chlorophyll-a and abundances could be because, in this work, the picoplankton photosynthetics were not quantified in both periods, whose lighting and mixing variables in the water column contributed to these differences.

Phytoplankton composition: In this study, 136 taxa were found, 68.4 % Heterokontophyta, followed by 22.8 % Dinoflagellata (Table 2); such composition is typical of euryhaline environments. That is, diatom and dinoflagellate dominance are similar to that registered in brackish aquatic Dzilam, Tamiahua and Mandinga Lagoons from Yucatan and Veracruz, Mexico (Figueroa-Torres & Weiss-Martínez, 1999; Herrera-Silveira et al., 1999; Salcedo-Garduño et al., 2019).

Of the total phycoflora, the following Phylum are cited for the first time: Cyanobacteria, Euglenophyta, and Chlorophyta; in the last Phylum, the Pseudopediastrum can grow in an oligohaline habitat whose salinity intervals range from 0 to 10 PSU. This genus is one of the typical phytoplankton components of a polyhaline environment such as Tamiahua Lagoon, where salinities are from 18 to 30 PSU (Figueroa-Torres & Weiss-Martínez, 1999). Otherwise, from the composition of the diatoms indicated by Barón-Campis et al. (2005), the presence of six genera Chaetoceros, Navicula, Pleurosigma, Pseudo-nitzschia, Skeletonema, and Thalassionema was confirmed, during the study, while the genus Lioloma was not recorded in this work.

The specific phytoplankton richness registered in Mandinga Lagoon can be rated as high, as opposed to what was indicated for other coastal lagoons in the Gulf of Mexico, such as Tamiahua with 39 species of Dinoflagellata (Figueroa-Torres & Weiss-Martínez, 1999), Alvarado with 18 species (Margalef, 1975), and Lagartos with 67 species (Nava-Ruíz & Valadez, 2012). We recognized 93 species of diatoms, of which the genera with the highest species richness were Chaetoceros with eleven and Nitzschia with seven. Krayesky et al. (2009) indicate similar data for the Southwestern Gulf of Mexico, where both genera present the highest richness with 27 and 16 species, respectively.

Pseudo-nitzschia species in the study area can warn about the need for surveillance as they are HAB-causing agents (Salcedo-Garduño et al., 2019). Regarding the Dinoflagellata, the studied stations registered 31 species, corresponding to 12 % of that indicated for the Southwest of the Gulf of Mexico (Steidinger et al., 2009), where the genus with the highest number of species was Protoperidinium with nine species. This taxon was mainly associated with the IA station, the closest area to the system’s mouth. Therefore, many of its components are typically marine, where 25 PSU were registered, conditions consistent with the high diversity of species defined by Okolodkov (2008) for the marine coasts of Veracruz, where 46 species of that genus were found. In three stations studied, B. quinquecornis was found in low 80 x 103 cells/ml concentrations. This species has been associated with HAB in the port of Veracruz (Barón-Campis et al., 2005), for which it is highly recommended to monitor the dynamics of this population to prevent future environmental contingencies in the study area.

For the Cyanobacteria, eight species were found only at the ICO and MCH stations, and M. elegans, M. insignis, and M. wesenbergii were registered for the first time. These taxa correspond to 18 % of those listed for the Southwest of the Gulf of Mexico (León-Tejera et al., 2009).

Abundance phytoplankton: Out of the ten abundant species in the study area, the maximum quantification corresponded to the 2018 period in the ICO station, with 307 x 103 cells/ml in the dry season. In contrast, the minimum concentration was 76 x 103 cells/ml in the MCH station in the wet season (Table 3). High amounts of productivity, if we compare them with the records of 4 x 103 cells/ml in the rainy and windy seasons at Alvarado’s Lagoon indicated by Margalef (1975). Therefore, both lagoons record minimum phytoplankton concentrations in the rainy season. This suggests a variation in the quantification of phytoplankton, which showed a higher record in the dry season when the depth of the Secchi disk was 43 cm, where the picoplankton could be essential components of chlorophyll production in the system. The support mentioned above was indicated by Kjerfve & Magill (1989); they say that, during the wet seasons, cyclone, hurricane, tropical storm, and waterspout seasons are associated, which produce changes in the ecosystem and its components, e.g., salinity, nutrients, winds, and the deposition of freshwater by the tributaries. For that reason, the phytoplankton cannot grow appropriately.

Instead, during the dry season, where conditions remain similar, some components of the phytoplankton can grow exponentially. The species with the highest abundance in the study area was B. paxillifera.

According to Jahn & Schmid (2007), this diatom, a ubiquitous taxon, has been recorded worldwide in freshwater, brackish, and marine habitats. Despite the changes in limnological conditions, these species do not experience growth limitations. Likewise, this species has also been indicated as an abundant component of 39 x 103 cells/L from Sontecomapan Lagoon, Veracruz (Muciño-Márquez et al., 2012).

Species dominance: Our results showed a phytoplankton composition mainly made up of diatoms and dinoflagellates in 91.6 %. This is consistent with some authors’ statements that Bacillariophyta and Dinoflagellata account for approximately 80 % of the eukaryotic species of marine phytoplankton (Licea et al., 2004; Licea et al., 2011; Muciño-Márquez et al., 2014). As well as the presence of Alveus marinus, Chaetoceros atlanticus, C. lorenzianus, D. bombus, N. pennata, N. granulata, N. longissima, S. costatum, Gonyaulax spinifera, Dinophysis fortii, Pseudo-nitzschia cf. pseudelicatissima, and P. cf. pungens, among others. This indicates seawater intrusion into the lagoon by tidal currents or wind, consistent with what was stated in studies for different coastal lagoons. As opposed to Lagartos Lagoon, Quintana Roo, more than 80 % of its phytoplankton comprises Cyanobacteria, which suggests that the system is eutrophicated (Nava-Ruíz & Valadez, 2012).

The highest Shannon-Wiener index in this study was 1.31 bits/ind., indicating some species’ high dominance and low equity. These results are lower than the one cited for the Palizada del Este Lagoon, Campeche-Mexico; there was an index of 3.2 bits/ind. (Muciño-Márquez et al., 2014). Also, in a marine region near Punta Limón, Veracruz, the data were from 1.9 to 4.1 bits/ind. (Santoyo & Signoret, 1988).

Relationship between phytoplankton and limnological variables: Some species of the abundant genera in this study, including Chaetoceros, Grammatophora, Gyrosigma, and Nitzschia (Table 2 and Table 3), have been used as indicators of salinity in previous studies and are associated with wide temperature ranges, which gives them the category of salinity eurythermal and euryhaline (Rivera-Guzmán et al., 2014).

Phosphates and salinity (zero) explain the presence of Chlorophyta species in the wet season at ICO (Table 2). This would be relevant for the variables indicated, as well as for the environmental conditions recorded, for example, some species of Pediastrum sensu lato for Central Europe and Mexico (Lenarczyk, 2015; Garduño et al., 2016).

On the other hand, nitrates, water temperature, and pH explain the presence of dinoflagellates in the dry season in ICO and IA. These results have also been recorded in the Celestun Lagoon, Yucatan, where dinoflagellates withstand wide temperature ranges (Herrera-Silveira et al., 1999). This group shows a correlation between temperature and abundance, which is consistent with the results obtained in this study. However, it should be noted that some species of the genera Ceratium, Prorocentrum, and Gyrodinium can tolerate salinities from 10 to 70 PSU (Taylor, 1978). In general, the limnological variable and the phytoplankton diversity show temporality, which reflects variations in the environment and the activities of human populations that depend directly or indirectly on the lagoon water, precipitation and deposition of the tributaries mainly. Salcedo-Garduño et al. (2019) indicated a shallow environment for Mandinga Lagoon with the influence of marine and continental water from the Jamapa River. They also report a more significant variability in the phytoplankton abundance during the wet season.

Ethical statement: the authors declare that they all agree with this publication and made significant contributions; that there is no conflict of interest of any kind; and that we followed all pertinent ethical and legal procedures and requirements. All financial sources are fully and clearly stated in the acknowledgments section. A signed document has been filed in the journal archives.

uBio

uBio