Introduction

The Amazon Rainforest stands out as one of the most important, extensive, and biodiverse biomes in the world (Foley et al., 2007; Mittermeier et al., 2003). This biome encompasses 62 % of Peruvian territory, making it the second largest country in terms of Amazon coverage after Brazil (Charity et al., 2016). Currently, the Amazon Rainforest faces various anthropogenic threats, such as agriculture, hunting, livestock, oil and gas extraction, mining, and infrastructure construction (Charity et al., 2016; Estrada et al., 2017; Francesconi et al., 2018; Gutiérrez-Vélez et al., 2011). These activities threaten the diversity and subsistence of many taxa, such as primates, causing their species to be considered in various categories of threat (Estrada et al., 2017; IUCN, 2023; Shanee et al., 2023). Therefore, the creation of areas dedicated to the conservation of Amazonian forests and the improvement of connectivity between them is essential (Bardales et al., 2023; Shanee et al., 2014; Shanee et al., 2017; Vuohelainen et al., 2012).

One of the prioritised areas for conservation in Peru is the Manu Biosphere Reserve (MBR), containing 19 different ecosystems across 1 881 200 ha, making it the largest reserve of Amazonian forest (UNESCO, 2020). It is considered one of the most biodiverse places in the world, harbouring 222 species of mammals (Patterson et al., 2006), 1 003 birds (Patterson et al., 2006), 132 reptiles (Catenazzi et al., 2013) and 155 amphibians (Catenazzi et al., 2013). Among these taxa, primates have proven to be important for the maintenance of many ecosystems such as those of the MBR (Andresen et al., 2018a; Estrada et al., 2017; Larcher et al., 2019).

The Order Primates is the third largest group of mammals in terms of species richness, surpassed only by the orders Chiroptera and Rodentia (Groves, 2005; IUCN, 2023). Peru is home to 42 of the 178 primate species documented in Central and South America (NPC, 2023; Pacheco, 2021). Half of Peruvian species are critically endangered without an effective framework to ensure their protection (Shanee et al., 2015; Shanee & Shanee, 2021). The decline in primate diversity compromises the ecosystem functions that they perform (Larcher et al., 2019).

The extent of the ecosystem functions, such as forest regeneration through seed dispersal, that a primate community can perform in a certain area depends on its complexity. This complexity is influenced by various factors such as inter and intraspecific competition; the vertical layer of the forests, availability of food resources, presence of suitable resting sites, hunting pressure, degree of disturbance and soil fertility, among others (Arcos et al., 2013; Balbuena de los Ríos, 2023; Chapman, 1995; De La Ossa et al., 2013; Del Águila-Cachique et al., 2020; Gómez & Verdú, 2012; Luna, 2013; Villota-Mogollón, 2023). Understanding the impact of these factors is crucial for devising effective primate conservation strategies in regions of high biodiversity. Therefore, the objectives of the present research were: (i) characterise the community of primates present in three types of forest with different degrees of historical disturbance, (ii) determine their preference in vertical stratification and (iii) estimate their pattern of hourly activity. Additionally, (iv) we discuss their implications as seed dispersers for the maintenance and regeneration of secondary forests in the MBR.

Materials and methods

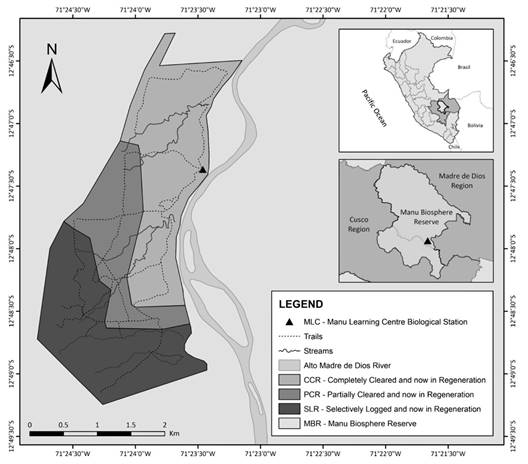

Study area (Fig. 1): The Manu Learning Centre (MLC) Biological Field Station is located within the MBR (12°47’21” S & 71°23’28” W; 470 m.a.s.l.), in the department of Madre de Dios, Peru. The MBR is made up of three parts: the core area, which has the highest level of protection; the buffer zone, with the objectives to protect indigenous groups, conduct scientific research, and develop tourist activities; and the transition zone, which does not have strictly defined limits and allows various anthropic activities such as hunting (Yallico & Suarez de Freitas, 1995). The MLC is in the buffer zone within a regenerating forest that covers 643 ha and has been strictly conserved for 20 years. It has previously been affected by various anthropogenic activities at different scales and is consequently divided into three types of forests based on the degree of historical disturbance.

Fig. 1 Types of forest according to the degree of historical disturbance found at Manu Learning Centre Biological Field Station (CCR, PCR and SLR), located within the Manu Biosphere Reserve in the Madre de Dios Region, Perú.

The most disturbed forest, Completely Cleared and now in Regeneration (CCR), was previously used for intensive agricultural activities (coffee, cocoa, and cotton), livestock grazing, and logging. Currently, this forest is characterised by having dense vegetation, mainly bushy. The maximum height of the trees is up to approximately 20 m, which results in a canopy that allows the passage of sunlight and favours the growth of pioneer species of Urticaceae, Melastomataceae and Rubiaceae.

The medium disturbance forest, Partially Cleared and now in Regeneration (PCR) was historically used for small-scale agricultural activities and selective extraction of timber trees. The trees in this area reach an average height of 30 m, with few open areas that allow limited access to light. The understory is characterised by being dense, with a moderate herbaceous cover. Among the most representative families are Lauraceae, Urticaceae and Arecaceae.

The least disturbed forest, Selectively Logged and now in Regeneration (SLR), previously was subjected to selective logging, and now features trees with an average height of 50 m and a broader canopy that limits the entry of sunlight. Most of the trees have robust trunks. The dominant families in this forest are Fabaceae, Meliaceae and Moraceae.

Data collection and statistical analysis: Two sets of historical data from Crees Foundation for Manu were used in the study, which correspond to incidental data and Terrestrial In-line Transect (TILT) surveys. For the incidental data, all the chance observations of primate species in the different routes made by the research team at different times of the day are recorded. We reduced the bias of a non-systematic methodology by having a varying schedule of fieldwork, between 03:00 and 00:00 h. On the other hand, TILT sampling is a systematic methodology of 1 500 m linear transects carried out in the three types of forest (CCR, PCR, SLR). In each forest, we set up two linear transects that were explored in the morning at 05:00 h and in the afternoon at 16:00 h.

The data set is composed of records from January 2011 to February 2023. Variables recorded in the database include the type of forest, the vertical stratum in which the species was first observed, and the time of recording. For incidental data, the complete database was used. For the analysis of TILT sampling data, due to the difference in the survey numbers, we randomly selected the minimum number (49 for each) to equalise the efforts and compare the three types of forest. To find preferences for a type of disturbed forest, the count of individuals by species was carried out in each forest type. Using this count, rank abundance curves, correspondence analyses, and Williams’ G goodness-of-fit tests were performed following the recommendations of Legendre & Legendre (1983) and McDonald (2014).

The rank abundance curves order the species by their abundance and allow us to see how the structure of the primate community varies between each of the forest types. In order to graphically observe if there is a marked preference towards a certain forest type, a correspondence analysis with type I scaling was carried out (Legendre & Legendre, 1983). Additionally, a Williams’ G goodness-of-fit test was performed, which allows us to compare whether the expected proportions are like the observed proportions (abundance by forest type) (McDonald, 2014). The expected proportions were calculated by equating the records in the three forest types, under the assumption that they would be the same if they did not show a preference for forest type.

For the hourly difference analysis, only the incidental data set was used. The periodic mean (mean angle, mean direction), periodic median (mean direction), fit to the von Mises distribution, Kuiper test, common median test (cm test) and Dunn’s post hoc test were determined following the recommendations of Dunn (1964), Fisher (1993), Zar (2010), Glantz (2012) and Pérez-Bote (2020). The periodic median and periodic mean were calculated to describe the data and were made based on the conversion of hours to radians, since these are the appropriate descriptors for circular data (Fisher, 1993; Pérez-Bote, 2020). The hourly frequencies were plotted in a rose diagram, accompanied by the periodic mean (intermittent line), periodic median (solid line) and von Mises distribution (circumference).

The von Mises distribution is equivalent to the normal distribution in linear statistics (Pérez-Bote, 2020). To see if the data conformed to the von Mises distribution, a Kuiper test was performed, which allows us to check if the data conforms to a theoretical distribution (Pérez-Bote, 2020). The common median analysis (cm test) is useful to see if the periodic medians of two datasets are different in a series of distributions, so it was used to test if there are differences between the activity period of the studied primates (Fisher, 1993). The cm test was carried out with all the species, except for those that had less than ten total records, because the test assumes sample sizes of greater than ten (Fisher, 1993). With the same data, Dunn’s post hoc test was performed with the “holm” adjustment, which allows multiple comparisons of non-parametric data with different sample sizes, and the “holm” adjustment reduces type I error (Dunn, 1964; Glantz, 2012; Zar, 2010). Then, the cm test was repeated with those data that did not present statistical differences in the post hoc test.

To study vertical stratification, four different strata were considered: high (> 12 m), medium (> 3-12 m), low (> 0-3 m) and terrestrial (0 m). A correspondence analysis and Williams’ G goodness-of-fit tests were performed, following the recommendations of McDonald (2014) and Legendre & Legendre (1983). Due to a limited number of records and the biology of the primates studied, we opted not to include the terrestrial stratum in any of our analyses. For data manipulation and statistical analysis, Python 3.11.3 was used with the packages Scipy 1.10.1, pandas 2.0.2, Matplotlib 3.7.1, EcoPy 0.1.2.2, Sklearn, collections, pycircstat (https://github.com/circstat/pycircstat/tree/master) and pycircular (https://github.com/albahnsen/pycircular).

Results

For incidental data: Nine primate species were documented in 5 333 records (Ateles chamek, Sapajus macrocephalus, Saimiri boliviensis, Plecturocebus toppini, Aotus nigriceps, Lagothrix lagothricha, Leontocebus weddelli, Alouatta sara, and Cebus albifrons) (Fig. 2, Table 1). The most frequently recorded species was P. toppini with 1 337 records, followed by S. macrocephalus with 1 136 records. There were more incidental records in CCR (2 904), followed by PCR (1 444) and finally SLR (985).

Table 1 Records of primates through incidental sampling at the Manu Learning Centre Biological Field Station in Manu Biosphere Reserve, Peru.

| Especie | CCR | PCR | SLR | TOT. | G_A | P_A | SH | SM | SL | ST | G_B | P_B | ||||||||||||

| H | M | L | T | S | H | M | L | T | S | H | M | L | T | S | ||||||||||

| A. chamek | 6 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 15 | 30 | 7 | 11 | 1 | 49 | 158 | 44 | 29 | 1 | 232 | 296 | 271.61 | 0.0000 | 194 | 57 | 43 | 2 | 132.34 | 0.0000 |

| S. macrocephalus | 125 | 359 | 115 | 5 | 604 | 126 | 188 | 65 | 1 | 380 | 60 | 67 | 25 | 0 | 152 | 1 136 | 289.22 | 0.0000 | 311 | 614 | 205 | 6 | 231.46 | 0.0000 |

| S. boliviensis | 103 | 393 | 183 | 3 | 682 | 58 | 176 | 85 | 1 | 320 | 22 | 34 | 17 | 2 | 75 | 1 077 | 566.81 | 0.0000 | 183 | 603 | 285 | 6 | 259.19 | 0.0000 |

| P. toppini | 295 | 545 | 314 | 6 | 1 160 | 53 | 64 | 34 | 1 | 152 | 10 | 9 | 5 | 1 | 25 | 1 337 | 1 748.28 | 0.0000 | 358 | 618 | 353 | 8 | 98.62 | 0.0000 |

| L. weddelli | 16 | 90 | 41 | 3 | 150 | 42 | 115 | 41 | 1 | 199 | 14 | 56 | 11 | 0 | 81 | 430 | 51.78 | 0.0000 | 72 | 261 | 93 | 4 | 141.22 | 0.0000 |

| A. nigriceps | 34 | 72 | 27 | 1 | 134 | 13 | 14 | 11 | 0 | 38 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 22 | 194 | 107.42 | 0.0000 | 56 | 94 | 43 | 1 | 21.11 | 0.0000 |

| L. lagothricha | 24 | 17 | 6 | 1 | 48 | 106 | 65 | 26 | 2 | 199 | 192 | 111 | 34 | 1 | 338 | 585 | 245.34 | 0.0000 | 322 | 193 | 66 | 4 | 183.99 | 0.0000 |

| A. sara | 73 | 16 | 17 | 0 | 106 | 67 | 17 | 22 | 1 | 107 | 47 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 58 | 271 | 18.75 | 0.0001 | 187 | 38 | 45 | 1 | 145.59 | 0.0000 |

| C. albifrons | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 7 | 7.00 | 0.0301 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 9.64 | 0.0081 |

Abbreviations: CCR: Completely Cleared in Regeneration, PCR: Partially Cleared in Regeneration, SLR: Selectively Logged and now in Regeneration, H: high stratum, M: middle stratum, L: low stratum, T: terrestrial stratum, S: sum by type of forest, TOT: overall, G_A: goodness-of-fit test statistic for differences in preferences for the degree of disturbance, P_A: level of significance of the goodness-of-fit test in preferences for a degree of disturbance, SH: high stratum sum, SM: middle stratum sum, SL: low stratum sum, ST: terrestrial stratum sum, G_B: goodness-of-fit test statistic for differences between strata, P_B: level of significance for the goodness-of-fit test for stratum preferences.

Fig. 2 Species of primates studied at Manu Learning Centre Biological Field Station. A. Ateles chamek, B. Sapajus macrocephalus, C. Saimiri boliviensis, D. Plecturocebus toppini, E. Aotus nigriceps, F. Lagothrix lagothricha, G. Leontocebus weddelli, H. Alouatta sara.

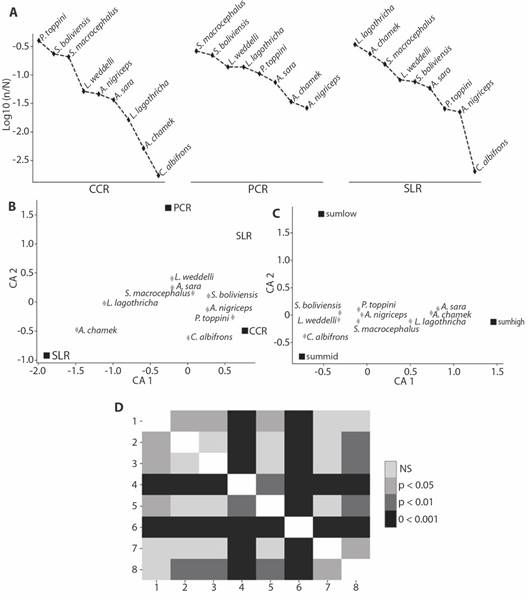

According to the abundance range curves (Fig. 3A) and correspondence analysis (CA1 = 93.61 %, CA2 = 6.38 %) (Fig. 3B), P. toppini has a marked preference for the most disturbed forest, presenting 87 % (1 160) of its records in CCR. S. boliviensis, S. macrocephalus, L. weddelli and A. sara are representative in the three types of forest. A. chamek and L. lagothricha present a high preference for SLR, the least disturbed forest type. These preferences towards a type of forest can be verified with the goodness-of-fit (Table 1), where a statistically significant difference was obtained between what is expected and what is observed (P < 0.01) for all species except C. albifrons, which presents too few records (seven) to make conclusions from the goodness-of-fit.

Fig. 3 Incidental data analysis of species of primates found in Manu Learning Centre Biological Field Station. A. Rank abundance curves of primate species records by forest type. B. Correspondence analysis of the preference of each species for a forest type (CCR, PCR and SLR) C. Correspondence analysis of the preference of each species for a stratum, sumlow (low stratum), summid (middle stratum) and sumhigh (high stratum). D. Dunn’s post hoc test comparing sample sizes of primate species, 1. Ateles chamek, 2. Sapajus macrocephalus, 3. Saimiri boliviensis, 4. Plecturocebus toppini, 5. Leontocebus weddelli, 6. Aotus nigriceps, 7. Lagothrix lagothricha, 8. Alouatta sara.

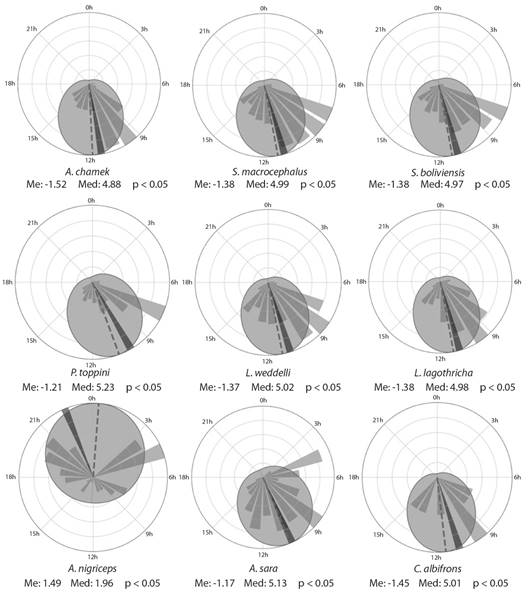

Regarding the hourly frequencies of incidental data (Fig. 4), most species were recorded in the morning from 06:00 to 12:00 h, except for A. nigriceps, which had more records at night between 18:00 and 05:00 h. None of the records present a von Mises distribution (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4), so when comparing their medians, it can be noted that in most species they are between 11:00 and 12:00 h, except for P. toppini, A. sara and A. nigriceps (Fig. 4). To check if there are differences between the medians, we applied the common median test where a CM = 44.33 and P < 0.05 was obtained, indicating that there are differences in the medians of their hourly frequencies. The species that are responsible for these differences are A. chamek, P. toppini, A. sara and A. nigriceps, showing differences in post hoc tests with the rest (Fig. 3B). When performing the common medians test again without these species, a CM = 0.9099 and P = 0.54 > 0.05 was obtained, finding that the rest of the species present equal medians.

Fig. 4 Rose plots of the hourly frequencies of incidental data by species of primates in the 24-time categories (0 to 23 h), showing the periodic median (radians) in intermittent line, the periodic mean (radians) in solid line and the von Mises distribution in circumference.

When comparing the vertical stratification of species, we found that the stratum most frequently used by primates is the middle stratum with 2 484 records, followed by the high stratum with 1 683 encounters and finally the low stratum with 1 134 (Table 1). The most recorded species in all strata was P. toppini (Table 1). When observing the correspondence analysis (Fig. 3C), A. sara, L. lagothricha and A. chamek show a marked preference towards the high stratum, and the rest of the species towards the middle stratum. This can be verified by the goodness-of-fit test, where significant statistical differences were obtained (P < 0.01) (Table 1).

For TILT data: Eight primate species were documented in 295 records (Fig. 2, Table 2). The most frequently recorded species was P. toppini with 116 records, followed by S. macrocephalus with 76 records. The least commonly recorded species was A. nigriceps with four records. More records were obtained in PCR (142), followed by CCR (103) and finally SLR (50).

Table 2 Records of primates through TILT sampling at the Manu Learning Centre Biological Field Station in Manu Biosphere Reserve, Peru.

| Especie | CCR | PCR | SLR | TOT. | G_A | P_A | SH | SM | SL | ST | G_B | P_B | ||||||||||||

| H | M | L | T | S | H | M | L | T | S | H | M | L | T | S | ||||||||||

| P. toppini | 54 | 17 | 2 | 0 | 73 | 34 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 116 | 60.60 | 0.0000 | 96 | 18 | 2 | 0 | 135.226 | 0.0000 |

| A. sara | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 15.88 | 0.0004 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 41.747 | 0.0000 |

| L. weddelli | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 12 | 1.41 | 0.4933 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 19.483 | 0.0001 |

| S. boliviensis | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 26 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 35 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 45 | 38.98 | 0.0000 | 27 | 15 | 3 | 0 | 22.084 | 0.0000 |

| S. macrocephalus | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 30 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 57 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 76 | 57.82 | 0.0000 | 46 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 65.024 | 0.0000 |

| A. nigriceps | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 4.29 | 0.1171 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3.244 | 0.1975 |

| L. lagothricha | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 10 | 15.47 | 0.0004 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21.972 | 0.0000 |

| A. chamek | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 13 | 28.56 | 0.0000 | 7 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 10.619 | 0.0050 |

Abbreviations: CCR: Completely Cleared in Regeneration, PCR: Partially Cleared in Regeneration, SLR: Selectively Logged and now in Regeneration, H: high stratum, M: middle stratum, L: low stratum, T: terrestrial stratum, S: sum by type of forest, TOT: overall, G_A: goodness-of-fit test statistic for differences in preferences for the degree of disturbance, P_A: level of significance of the goodness-of-fit test in preferences for a degree of disturbance, SH: high stratum sum, SM: middle stratum sum, SL: low stratum sum, ST: terrestrial stratum sum, G_B: goodness-of-fit test statistic for differences between strata, P_B: level of significance for the goodness-of-fit test for stratum preferences.

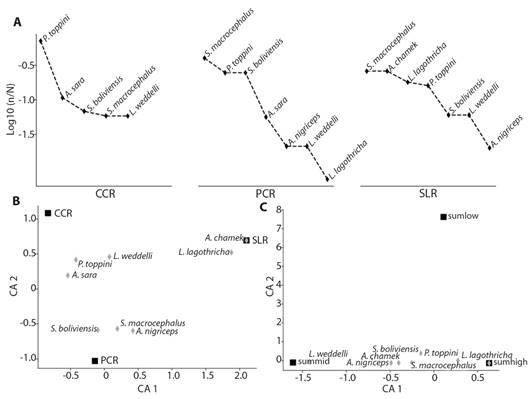

According to the rank abundance curves (Fig. 5A) and correspondence analysis (CA1 = 62.43 %, CA2 = 37.56 %) (Fig. 5B), three species showed a marked preference for CCR: P. toppini, presenting 59 % (62) of its records in this forest type; A. sara with 58 % (11) and L. weddelli with 50 % (six). S. boliviensis, S. macrocephalus and A. nigriceps showed a preference for PCR. Finally, A. chamek and L. lagothricha showed a high preference for SLR. These preferences towards a type of forest can be verified with the goodness-of-fit test (Table 2), which shows that the observed frequencies are different from those expected (P < 0.01) in P. toppini, A. sara, A. chamek, S. boliviensis, S. macrocephalus and L. lagothricha.

Fig. 5 TILT data analysis of species of primates found in Manu Learning Centre Biological Field Station. A. Rank abundance curves of primate species records by forest type. B. Correspondence analysis of the preference of each species for a forest type (CCR, PCR and SLR) C. Correspondence analysis of the preference of each species for a stratum, sumlow (low stratum), summid (middle stratum) and sumhigh (high stratum).

When comparing the vertical distribution, we found that the stratum most frequently used by primates was the high stratum with 208 records, followed by the middle with 82 and finally the low with five (Table 2). The most frequently recorded species in the high stratum was P. toppini (96); in the middle stratum, S. macrocephalus (30); and the low stratum, S. boliviensis (three). In the correspondence analysis (Fig. 5C), P. toppini, A. sara, S. boliviensis, S. macrocephalus and L. lagothricha prefer the high stratum; L. weddelli for the medium, and A. chamek and A. nigriceps for medium and high. This can also be verified by a goodness-of-fit test, where statistical differences were found between the observed and expected frequencies (P < 0.01) for all species except A. nigriceps (Table 2).

Discussion

Preferences for forest type: In the study, the primate community exhibited changes along the disturbance gradient, driven by the preferences of certain species. Specifically, L. lagothricha and A. chamek displayed a preference for SLR, the least disturbed forest type, while P. toppini exhibited a preference for CCR, the most disturbed forest type. The species L. lagothricha and those of the genus Ateles have previously been documented to favour tall primary forests. This preference is attributed to the presence of suitable tree cover for their movement, the abundance of food resources supporting their populations, and the high potential for protection from predators afforded by these forests (Campbell et al., 2005; Di Fiore, 2002; Emmons & Gentry, 1983; Luna, 2013; Marsh et al., 2016; Parry et al., 2007; Ramos-Fernández & Ayala-Orozco, 2003; Rivas-Rojas et al., 2019; Roncancio et al., 2010; Wallace et al., 1998). For this reason, the structure and vegetal composition of SLR allows the subsistence of these species; while the other two forest types, PCR and CCR, only constitute displacement areas.

The preference for more disturbed forests in Plecturocebus, as we observed in P. toppini, has also been reported for other members of the genus, being present in secondary and anthropogenised forests with different levels of disturbance (Defler & Carretero-Pinzón, 2018; DeLuycker, 2006; García et al., 2010; Shanee et al., 2013; van Kuijk et al., 2016). This is because they could modify their behaviour and foraging strategies according to the availability of food (Hodges, 2020; Nagy-Reis & Setz, 2017).

A. sara, S. boliviensis, L. weddelli and S. macrocephalus did not show a clear preference towards a forest type. These species have been reported to present relative tolerance to disturbance, being found in secondary forests and in more conserved forests (Aquino et al., 2013; Buchanan-Smith et al., 2000; Garber et al., 2006; Garber et al., 2015; Göbel & Heymann, 2018; Peres, 1993; Stevenson et al., 2015; Van Belle & Estrada, 2006; Wolfheim, 1983). This relative tolerance may be due to their diet. The diet of species of the genus Alouatta includes mature leaves, flowers, leaf and flower buds, and mature and immature fruits of families such as Apocynaceae, Arecaceae, Moraceae and Melastomataceae, allowing them to find food in any type of forest (Chapman, 1987). The diet of S. boliviensis and L. weddelli consists predominantly of insects, which are also very abundant and varied in any type of forest (Fowler et al., 1993; Soini, 1987). Although species in the genus Sapajus are considered highly adaptable and without a clear preference, it has been reported that some capuchins prefer to roost in areas of mature forest with larger trees, showing a slight preference for more conserved forests (Smith et al., 2018). In contrast, in the MLC they have refuges in the three types of forest, which may be related to the strict protection of the area.

The MLC demonstrates that a forest that has passed through varying degrees of human disturbance, today could constitute a habitat for bioindicator species of healthy ecosystems such as Lagothrix spp. and Ateles spp., and play a pivotal role in providing resources and protection for the primate community (Rivas-Rojas et al., 2019). Its significance in conserving these valuable habitats underscores the pressing need for increased government support and funding to ensure the continued preservation of this vital ecosystem.

Vertical stratification: The use of vertical stratification in primates is closely linked to various factors, including intraspecific competition, foraging strategies, and the potential presence of terrestrial predators (Arcos et al., 2013; De La Ossa et al., 2013). This last aspect influences the occurrence in the lower and terrestrial strata, supporting our results, as the number of recorded instances is significantly lower in these strata.

A relationship between primate size and stratum use has been demonstrated (Arcos et al., 2013; Pozo, 2004). Our findings indicate that larger primates, such as A. chamek, L. lagothricha, and A. sara, exhibit a preference for the upper stratum. This preference is attributed to the opportunities it provides for engaging in locomotor activities, the abundance of phytomass, and the high net production of leaves and fruits, vital resources in the diet of these species. These patterns align with previous research (Pozo & Youlatos, 2005). On the other hand, P. toppini, S. boliviensis and S. macrocephalus were observed in mid to upper strata, which may be associated with adopting a broader field of vision within the forest. This potentially constitutes a strategy to avoid semi-arboreal predators such as ocelots (Leopardus spp.), pumas (Puma concolor), and tayras (Eira barbara) present in the study area or to identify potential competitor groups (Arcos et al., 2013; De La Ossa et al., 2013). The flexibility in foraging strategies could be another reason for their distribution in these strata, as they disperse and use various fruit-bearing trees, consuming in all strata simultaneously or sequentially, adapting to the forest’s production cycles (De La Ossa et al., 2013). These same factors are considered for L. weddelli and A. nigriceps, demonstrating a pronounced inclination towards the middle stratum.

Activity period: Primates exhibit a wide range of temporal activity patterns (Santini et al, 2015; Tattersall, 1987). According to the hourly frequency of each species, seven (L. lagothricha, A. chamek, A. sara, S. macrocephalus, L. weddelli, S. boliviensis and P. toppini) of the eight species studied were recorded during the day, agreeing with the activity patterns described in their ecology (Santini et al, 2015). A. nigriceps was recorded mostly during the night, agreeing with previous reports of the species (Santini et al, 2015; Wright, 1978; Wright, 1989; Wright, 1996). The few records during the day of A. nigriceps may be since they show cathemerality, during certain times of the year (Khimji & Donati, 2014).

Sympatry in primates is possible due to a differentiated use of habitat, food resources, vertical stratification, foraging techniques, and temporal activity segregation, avoiding competition (De La Ossa et al., 2013; Peres, 1993; Pozo & Youlatos, 2005; Stevenson et al., 2000). Our results show no significant difference between the temporal activity of four sympatric species (L. lagothricha, S. macrocephalus, L. weddelli, S. boliviensis). Consequently, it is imperative to direct our subsequent efforts toward comprehending the strategies employed by these species to mitigate competition.

Implications of primates as seed dispersers: The ecological importance of primates is due to the great variety of preferences that species present to different factors (disturbances, vertical strata, and activity time), being able to develop different functions in the ecosystem such as seed dispersal. The ability to disperse seeds by primates is highly related to the use of the forest and the size of the individual (Bufalo et al., 2016; Fuzessy et al., 2017; Peres & van Roosmalen, 2002; Sales et al., 2020). In our study, the presence of large frugivorous species such as A. chamek and L. lagothricha in the less disturbed forest makes them the main seed dispersers in this type of forest and to a lesser extent in those with greater disturbance. These species are considered unique dispersers due to their ability to move easily through the forest, and to handle and consume large quantities of fruits (Luna, 2013; Peres & van Roosmalen, 2002; Stevenson et al., 2002). Unlike these two species, the seed dispersal capacity of another large species, A. sara, is reduced by its difficulty in handling fruits and its more flexible diet, being able to consume leaves and branches (Crockett, 1998; Peres & van Roosmalen, 2002).

In more disturbed forests, seed dispersal occurs mainly through species of medium (S. macrocephalus) and small size (S. boliviensis, L. weddelli, A. nigriceps and P. toppini) because they can withstand disturbance at greater levels. Medium-sized species require greater connectivity and consume fruits with almost no type of restriction (de A. Moura & McConkey, 2007; Wehncke & Domínguez, 2007; Wehncke et al., 2003). Contrastingly, the smaller ones do not require extensive areas of forest and are able to move between patches with small trees, even using the terrestrial stratum (Milton & May, 1976). Due to their ability to move in small trees, smaller primates play a role in the recovery of connectivity and maintenance of the diversity of the Amazon Rainforest in places impacted by humans (Andresen et al., 2018b; Chagas & Ferrari, 2010; Culot et al., 2010; Gestich et al., 2019; Helenbrook et al., 2020; Knogge & Heymann, 2003; Luna et al., 2016; Müller 1996; Oliveira-Silva et al., 2018; Paim et al., 2017; Stone, 2007).

The ability to survive in secondary forests is an important factor for the conservation of these species and it provides a unique opportunity to study their ecology and adaptability to different degrees of disturbance. Studies related to primates and their tolerance to secondary forests are still scarce. The MLC Biological Field Station is home to threatened species (A. chamek and L. lagothricha), so this work is important because it provides information on the requirements of these species for their subsistence. We hope that the results presented are complemented by more detailed studies on the use and preference of habitat in secondary forests and their importance in the regeneration process, since this knowledge is essential for the design of conservation strategies and identification of priority sites for the protection of species.

Ethical statement: the authors declare that they all agree with this publication and made significant contributions; that there is no conflict of interest of any kind; and that we followed all pertinent ethical and legal procedures and requirements. All financial sources are fully and clearly stated in the acknowledgments section. A signed document has been filed in the journal archives.

uBio

uBio