Introduction

As coral reefs worldwide are declining, active solutions have been developed over the last few decades in order to reverse this alarming trend and restore the function of these ecosystems (Hughes et al., 2019; Lirman & Schopmeyer, 2016; Unsworth et al., 2020). Coral gardening is a popular technique to reestablish coral populations and increase coral cover (Ladd et al., 2019; Rinkevich, 1995); this strategy uses fragments from wild donor colonies and grows them in nurseries, followed by their outplanting to a degraded reef (Rinkevich, 2014). Even though the nursery stage of coral restoration and propagation methodologies are well-established, outplanting success can vary, with an average survival of 66 % of the outplanted corals (Boström-Einarsson et al., 2020), but with some projects reporting a higher survival of up to 89 % (Ware et al., 2020). However, the time frame considered to monitor outplant survival is often short, as most projects do so during a 12-month period (Boström-Einarsson et al., 2020). Coral outplants can undergo rapid mortality due to several stressors, both abiotic and biotic, such as temperature, disease, predation, and presence of competitor species (Cano et al., 2021; Foo & Asner, 2020; Hughes et al., 2017; Koval et al., 2020; Miller et al., 2014; van Woesik et al., 2017; Ware et al., 2020). Hence, there is increasing interest in developing techniques that could improve the efficiency and long-term success of such efforts (Lohr et al., 2020).

Several techniques exist for outplanting coral colonies or fragments onto either suitable natural reef substrate or artificial structures (Ferse et al., 2021). Most restoration practitioners use marine epoxy, cable ties, steel cables or nails to attach corals onto the substrate (Boström-Einarsson et al., 2020; Goergen & Gilliam, 2018; Omori, 2019). Which technique is the most appropriate is highly site-specific, depending on the type of substrate, currents, wave action, herbivore presence, and even colony size and density (Goergen & Gilliam, 2018; van Woesik et al., 2017). Thus, these considerations should be taken into account for the outplanting design before scaling up outplanting efforts.

Therefore, the success of the outplanting stage will also be inevitably affected by the appropriate selection of the outplanting site, which must gather conditions that promote coral survival and growth (see Kleypas et al., 1999). These include environmental factors such as seawater temperature (Coles & Jokiel, 1978; Foo & Asner, 2020), pH (Kleypas & Yates, 2009), nutrients, salinity (D’Angelo & Wiedenmann, 2014; Faxneld et al., 2010; Wiedenmann et al., 2013), and light (Coles & Jokiel, 1978; Foo & Asner, 2021); and biological factors like the presence of associated organisms such as fish, invertebrates, and other benthic groups (Cano et al., 2021; Rivas et al., 2021). Furthermore, intrinsic factors such as the coral species, life history, acclimation to local conditions, and genotype have an equally important role in shaping restoration outcomes (Baums et al., 2019; Goergen & Gilliam, 2018; Lirman et al., 2014).

Once transplanted, monitoring coral outplants is key for measuring outplanting success and thus, evaluating restoration efforts (Edwards, 2010; Foo & Asner, 2020). Despite the lack of standardised monitoring guidelines, outplant survival and growth rate are some of the most widely used assessments for this purpose (Hein et al., 2017; Edmunds & Putnam, 2020).

In the Eastern Tropical Pacific (ETP), coral restoration experiences are limited compared to other regions such as the Indo-Pacific and Caribbean region (Bayraktarov et al., 2020). In recent years, however, restoration initiatives in the ETP are rapidly increasing, and most of them focus on the branching coral genus Pocillopora (Chomitz, 2021; Combillet et al., 2022; Ishida-Castañeda et al., 2020; Liñán-Cabello et al., 2011; Tortolero-Langarica et al., 2014; Tortolero-Langarica et al., 2019). Direct transplantation in the Central Mexican Pacific showed a survival rate between 89-95.5 % over 270 days (Liñán-Cabello et al., 2011), which go in concordance with results in Colombia, which show 100 % survival after 5-months using nursery-reared Pocillopora fragments (Ishida-Castañeda et al. 2020), with higher growth rates than direct transplants. Outplanting using micro-fragmentation has only been implemented once in the ETP (Tortolero-Langarica et al., 2020), but never in Costa Rica, where only two studies have focused on Pocilloporaspp. outplanting success; Guzmán (1991) reported a 79-83 % survival in Caño Island, while Chomitz (2021) reports 83 % survival and an average 68 % growth in area along eight months of study in Golfo Dulce, both in the South Pacific of the country. However, this data cannot be extrapolated as environmental conditions between areas of the Pacific coast of Costa Rica are different, as are reef dynamics and the main coral reef-building species, mainly due to the presence of a seasonal upwelling and lower precipitation in the North Pacific of the country (Cortés et al., 2010).

This study represents the assessment of the first restoration project in the area, in order to evaluate the outplanting success of the first nursery-reared corals outplanted onto a degraded reef, therefore we aimed to (1) monitor the health and survival of outplanted colony fragments of the branching Pocillopora spp. and massive Pavona gigantea (Verrill, 1869), Pavona clavus (Dana, 1846) and Porites lobata (Dana, 1846) corals in Bahía Culebra, North Pacific of Costa Rica, (2) quantify the growth rate of outplanted corals in terms of area and diameter and (3) determine whether the origin (donor colonies sites) of the coral fragment and presence of upwelling have an effect on coral growth for Pocillopora spp. colonies, one year post-outplanting.

Materials & methods

Study area: Bahía Culebra (10°37’N - 85°39’W) is a semi-enclosed bay in the Gulf of Papagayo, North Pacific of Costa Rica (Fig. 1). The bay extends for more than 20 km2, and reaches its maximum depth at about 42 m (Rodríguez-Sáenz & Rodríguez-Fonseca, 2004). It is influenced by seasonal upwelling from December to April, causing a decrease in seawater temperature up to 10 ºC from the annual mean (27 ± 0.1 ºC) (Jiménez, 2001; Jiménez et al., 2010), and bringing up more acidic (pH 7.8) nutrient-rich waters (Rixen et al., 2012; Sánchez-Noguera et al., 2018b; Stuhldreier et al., 2015).

Fig. 1 Location of Güiri-Güiri outplanting site (yellow square), Jícaro nursery site (red star), and donor colonies sites (blue dot) in Bahía Culebra, North Pacific of Costa Rica.

Bahía Culebra once harboured some of the most extensive coral reefs on the Pacific coast of the country, mainly built by the branching coral Pocillopora, with high live coral cover (44.0 ± 0.3 %) (Jiménez 2001; Cortés & Jiménez, 2003). However, in the last two decades, coral reefs in the bay experienced intense coral bleaching and mass coral mortality (Sánchez-Noguera, 2012) caused by El Niño Southern-Oscillations (ENSO) events, increase in anthropic eutrophication and frequent harmful algal blooms (Fernández, 2007; Jiménez, 2007; Sánchez-Noguera, 2012), resulting in an abrupt loss of coral cover. This situation favoured the recruitment and proliferation of macroalgae (Alvarado et al., 2018; Fernández-García et al., 2012), and a cascading effect on high densities of the sea urchin Diadema mexicanum (A. Agassiz, 1863). As a consequence of sea urchin bioerosion, the coral framework weakened and was undermined (Alvarado et al., 2012; Alvarado et al., 2016). In order to mitigate the damage, a coral restoration project was initiated in Bahía Culebra in September 2019, by using coral gardening techniques and a subsequent transplant to nearby sites in the bay (Fabregat-Malé et al., in prep.).

Experimental design: The species of corals used in this study were the branching Pocillopora genus, and the massive P. gigantea, P. clavus, and P. lobata. Here, we worked with Pocillopora damicornis (Linnaeus, 1758) and Pocillopora elegans (Dana, 1846). To visually distinguish these species based on their morphology is equivocal (Pinzón et al., 2013); thus, considering their functional and genetic similarities (Pinzón & LaJeunesse, 2011; Pinzón et al., 2013), they were grouped and further referred as “Pocillopora spp.”. Coral fragments had been previously obtained from donor colonies on different reefs and coral communities around Bahía Culebra (Fig. 1). Donor colonies were randomly selected at depths between 2-7 m, growing at least 5 m from each other so as to maximize chances of sampling distinct genets. For Pocillopora spp., five fragments of about 2-5 cm were originally extracted from each donor colony, while for massive species (P. clavus, P. gigantea and P. lobata), microfragments of around 1.5-2 cm2 were obtained, using a diamond band saw (Model C-40, Gryphon, USA) (Fabregat-Malé et al., in prep.).

Nursery-reared coral colonies were outplanted in September 2020 to Güiri-Güiri reef (10° 36’ 49.7” N, 85° 41’ 24.1” W), in Bahía Culebra (Fig. 1), after a one-year cultivation in the nurseries. The reef formation in Güiri-Güiri is mainly built by dead Pavona framework, and some sparse Pocillopora, P. gigantea and P. clavus colonies (Jiménez, 1997; Jiménez, 2007). Coral colonies were outplanted at 5 m depth and on dead coral substrate, comprising an area of approximately 100 m2 on the back-reef area.

A total of 30 Pocillopora spp. colonies were tagged and outplanted onto the dead coral substrate using steel nails and cable ties (Fig. 2A), with a minimum distance of 50 cm from each other. Nursery-reared Pocillopora spp. colonies originally came from six different donor sites on the bay (Fig. 1): Matapalo (n = 11), Sombrero (n = 7), Esmeralda (n = 4), Jícaro (n = 4), Güiri-Güiri (n = 3), Palmitas (n = 1). For the massive coral species, an underwater drill (Nemo V2, NemoPowerTools, USA) was used to outplant 31 fragments (n = 18 P. gigantea fragments, n = 8 P. clavus, and n = 5 P. lobata), which were then fixed to the substrate using marine epoxy glue (Marine-Tex, USA) (Fig. 2B). The small sample sizes of massive species used during outplanting are due to their low survival in the nursery stage (Fabregat-Malé et al., in prep.). Massive fragments from the same species and genotype (i.e., donor colony) were outplanted together (2 cm apart) so as to promote fusion when growing (Forsman et al., 2015).

Fig. 2 A. Outplanting technique for nursery-reared Pocillopora spp. colonies and B. for massive species (Porites lobata, Pavona gigantea and Pavona clavus) fragments, in Güiri-Güiri reef, Costa Rica.

Monitoring occurred monthly post-outplanting for 12 months, from September 2020 to September 2021. The survival of each individual colony and fragment (alive, pale/bleached, dead or lost) was recorded, as well as partial tissue mortality. Coral growth was also recorded monthly, establishing a photoquadrat around each colony using a polyvinyl chloride (PVC) frame (30x30 cm) that held the camera above the substrate and the coral colonies. Photographs were taken from the same angle and direction, with a scaling object, using a Nikon COOLPIX W300 underwater camera. Each image was analysed using the photo-analysis software PhotoQuad (Trygonis & Sini, 2012), in order to calculate the area of outplanted coral colonies (cm2) and colony diameter (cm), evaluating lateral growth of colonies. Additionally, sea urchin D. mexicanum density was also censed, using belt-transects 10 x 2 m (20 m2) along the outplanting area, and used as an indicator of bioerosion and potential population controller of other groups (i.e., macroalgae and turf) through herbivory (Alvarado et al., 2012).

To determine the environmental conditions to which coral outplants were subject, seawater temperature at site was recorded every 30 min using HOBO® data loggers. Six water samples were collected in situ monthly to determine salinity (PSU) and nutrient concentration (NO3 -, NO2 -, PO4 3-, NH4 +, and SiO4), using a plastic syringe with a 1 µm glass microfiber filter, and were later processed using a field refractometer (PCE-0100, PCE Instruments, Germany) and a continuous flow autoanalyzer (QuikChem 8500, Lachat Instruments, USA), respectively.

Data analysis: Survival curves between species were compared using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test. Lost fragments were considered as “dead” for calculating survival rates. Differences in outplant size from initial to final month were analysed using a Student’s t-test. Growth rate of coral outplants was calculated over the first year after transplantation; the area (cm2) and diameter (cm) of each Pocillopora spp. colony and massive fragment were subtracted from the measurement of the following month. Growth rate results from colonies and fragments that had survived throughout monitoring period. Pocillopora spp. growth rates (cm mo-1) between upwelling and non-upwelling season were compared using a Student’s t-test. Differences in Pocillopora growth rate (cm2 mo-1) between sites of origin of donor colonies were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey HSD post-hoc tests. Palmitas was excluded as a donor site from this analysis as only one colony from this site was outplanted. Growth rates between massive species were also compared using a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test. Data were tested for normality and equality of variances using the Shapiro-Wilk test and Bartlett test, respectively, to ensure they met model assumptions. Statistical analyses were performed using R (R Core Team, 2021).

Results

Outplant survival: Exactly one year after their transplantation to the Güiri-Güiri reef, 100 % of the Pocillopora spp. outplants survived, none were lost, and no bleaching occurred. When grouping massive species together, overall survival by the end of the first year was 48.4 % (P. clavus = 71.4 %, P. gigantea = 47.5 %, and P. lobata = 20.0 %) (Fig. 3). Decrease in massive species survival was a result of the loss of fragments during monitoring period, not their death. This decline in survival in massive species was most pronounced in August 2021. Survival curves significantly differed only between P. clavus and P. lobata (D = 0.727, P < 0.05). Partial mortality and predation marks were only observed in outplants of massive species, with 22 fragments (71 %) having experienced partial tissue loss at least once during monitoring period (Fig. 4). Paleness in P. lobata fragments was observed in December 2020, but fragments recovered their coloration the following month.

Fig. 3 Cumulative survivorship (%) of massive coral fragments (Pavona clavus n = 8, in red; Pavona gigantea n = 18, in yellow; and Porites lobata n = 5, in blue) in the outplanting site of Güiri-Güiri, Costa Rica, through monitoring period (September 2020-September 2021).

Fig. 4 Percentage (%) of outplanted fragments of massive species (Pavona clavus, in red; Pavona gigantea, in yellow; and Porites lobata, in blue) exhibiting partial tissue loss through monitoring period (September 2020 to September 2021) in Güiri-Güiri reef, Costa Rica.

Outplant growth: Pocillopora spp. colonies were initially 63.24 ± 36.48 cm2 (8.66 ± 2.38 cm in diameter). One year after outplanting, colonies significantly grew to 273.91 ± 105.81 cm2 and 18.64 ± 3.46 cm in diameter (F 1,58 = 106.3, P < 0.005) (Fig. 5). This represents a 333.1 % increase in area, and a 115.2 % increase in diameter from initial size. The rate of change in area of the Pocillopora spp. outplants was calculated to be 17.56 ± 6.28 cm2 mo-1 (9.98 ± 1.69 cm yr-1) (Table 1).

Table 1 Initial and final sizes (mean area and diameter ± SD), and mean growth rate (± SD) of outplanted species to Güiri-Güiri restoration site, Costa Rica.

| Species | Initial size | Final size | Growth rate (cm2 yr-1) | ||

| Area (cm2) | Diameter (cm) | Area (cm2) | Diameter (cm) | ||

| Pocillopora spp. | 63.24 ± 36.48 | 8.66 ± 2.38 | 273.91 ± 105.81 | 18.64 ± 3.46 | 210.67 ± 75.41 |

| Pavona gigantea | 5.29 ± 1.25 | 2.24 ± 0.28 | 13.61 ± 2.87 | 4.11 ± 0.35 | 8.18 ± 2.29 |

| Pavona clavus | 4.37 ± 0.91 | 2.37 ± 0.49 | 11.43 ± 1.43 | 3.80 ± 0.20 | 6.69 ± 1.63 |

| Porites lobata | 4.60 ± 1.25 | 2.40 ± 0.35 | 7.84 | 3.16 | 2.77 |

Fig. 5 A. Increase of Pocillopora spp. colony area (cm2) from September 2020 to September 2021, B. and growth of the same Pocillopora spp. outplant at the start of monitoring period (left), after six months (middle), and after one year (right), in the outplanting site in Güiri-Güiri reef, Costa Rica.

Despite the loss, massive species significantly increased their area from initial size in 157.3 % for P. gigantea fragments (R 2 = 0.6421, F 1,147 = 266.6, P < 0.005), 161.6 % for P. clavus (R 2 = 0.7496, F 1,76 = 231.5, P < 0.005), and 70.4 % in P. lobata (R 2 = 0.5452, F 1,25 = 32.17, P < 0.005). Growth rates for massive species were 1.35 ± 0.24 cm yr-1 for P. clavus, 1.48 ± 0.21 cm yr-1 for P. gigantea and 0.61 cm yr-1 for P. lobata (Fig. 6, Table 1). Growth rates between massive species did not differ statistically (F 2,220 = 2.934, P = 0.0553).

Fig. 6 Changes in area (cm2) of outplanted fragments of massive fragments (Pavona clavus, in red; Pavona gigantea, in yellow; and Porites lobata, in blue) over monitoring period (September 2020-September 2021) in Güiri-Güiri reef, Costa Rica.

Monthly average growth rate of Pocillopora spp. outplants showed statistical differences through time, with a post-hoc Tukey test revealing lower growth rates in October 2020 (P = 0.0941).

Outplant growth and environmental conditions: Mean seawater temperature in the outplanting site was 27.75 ± 1.90 ºC, with a minimum of 19.08 ºC and a maximum of 30.52 ºC (Appendix 1). Significant differences in temperature between upwelling (26.47 ± 1.87 ºC) and non-upwelling season (29.00 ± 0.76 ºC) were detected (t 11437 = 117.08, P < 0.0005). Mean seawater salinity was 33.18 ± 1.05 PSU, and was significantly higher during dry season (33.72 ± 0.81 PSU) than during rainy season (32.71 ± 0.72 PSU) (t 369.47 = -12.906, P < 0.005) (Appendix 2). Nutrient concentration was highly variable and did not show any pattern (Appendix 3). Nitrate was the only nutrient whose concentration differed between upwelling and non-upwelling season, with higher concentrations during the non-upwelling rainy season (F 1,11 = 6.667, P < 0.05, Table 2). Despite the observed environmental differences between upwelling and non-upwelling season, Pocillopora spp. growth rate was not affected (F 1,358 = 2.955, P = 0.0865).

Table 2 Nutrient concentration (µM) in outplanting site Güiri-Güiri, Costa Rica, from September 2020 to September 2021.

| Nutrient | Mean (± SD) | Maximum | Minimum | Upwelling season (mean ± SD) | Non-upwelling season (mean ± SD) |

| Nitrate (NO3 -) | 3.82 ± 2.06 | 7.23 | 1.30 | 2.51 ± 0.33* | 4.95 ± 2.28* |

| Nitrite (NO2 -) | 3.03 ± 0.38 | 3.79 | 2.48 | 2.85 ± 0.22 | 3.19 ± 0.43 |

| Phosphate (PO4 3-) | 0.13 ± 0.13 | 0.34 | UDL | 0.16 ± 0.17 | 0.11 ± 0.09 |

| Ammonium (NH4 +) | 4.76 ± 1.17 | 6.71 | 2.93 | 5.18 ± 1.26 | 4.40 ± 1.04 |

| Silicate (SiO4) | 1.97 ± 2.83 | 7.93 | UDL | 2.02 ± 3.34 | 1.93 ± 2.59 |

Upwelling season: November to April; Non-upwelling season: May to October. UDL = under detection limit (0.48 µM). * = P < 0.05.

Finally, mean density of Diadema mexicanum in the outplanting area was 21.71 ± 1.48 ind m-2.

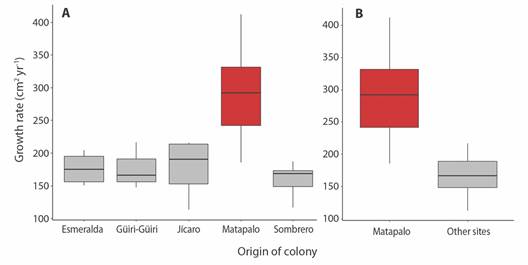

Influence of sites of origin on Pocillopora spp. outplant growth: Growth rate of Pocillopora spp. coral colonies differs by site of origin (F 5,354 = 10.13, P < 0.005) (Fig. 7A), as Matapalo outplants presented a higher growth rate (23.81 ± 17.56 cm2 mo-1, or 285.66 ± 69.82 cm2 yr-1) than the rest of the donor sites (overall mean = 13.94 ± 9.10 cm2 mo-1, or 167.25 ± 32.02 cm2 yr-1) (P < 0.05) (Fig. 7B).

Discussion

Identifying the causes of low survivorship in coral outplants is crucial to improve restoration techniques and their long-term effectiveness (Liñán-Cabello et al., 2011; Ware et al., 2020). In order for coral outplants to become a resource for other organisms, reproduce through fragmentation or sexual mechanisms, and contribute to reef complexity until no further transplantation and/or individual monitoring of the colonies is needed, it is important that they survive during the first year after transplantation and keep growing (Goergen & Gilliam, 2018). While all the outplanted Pocillopora spp. colonies survived during the first year after transplantation, over 50 % of the massive outplants were lost and 67.7 % of the remaining fragments experienced partial mortality and tissue loss, which is common for species with massive growth (Rivas et al., 2021) Different factors could explain the low survivorship in our results: (i) the process of microfragmentation may damage healthy tissue, in addition to their smaller sizes, which increase their vulnerability to other stressors (Arnold et al., 2010; Forsman et al., 2015), and may result into partial tissue mortality. Nonetheless, microfragments grow at a faster rate than larger corals (Page et al., 2018) and isogenic fusion of fragments may be used for colonies to reach a larger size in a shorter period of time (Forsman et al., 2015); and (ii) the technique implemented, due to the ceramic disk being mechanically dislodged by currents or the interaction of other reef species (Shafir & Rinkevich, 2013; van Woesik et al., 2017), including the presence of herbivores or predators. Large and dense patches of the sea urchin D. mexicanum (up to 28.5 ind m-2) were recorded during monitoring, covering the areas where massive corals had been outplanted. Their bioerosive activity may have promoted partial tissue mortality and interrupted the calcification process, which is essential for coral attachment to the natural substrate (Herrera-Escalante et al., 2005; Omori, 2019). In addition, fragments were damaged by fish bites. Predation by reef fish is one of the main drivers of mortality for small coral recruits or, in this case, outplants of sizes ≤ 5 cm2 (Ishida-Castañeda et al., 2020; Page et al., 2018; Palacios et al., 2014; Rivas et al., 2021), which decreases dramatically when fragments reach ≥ 25 cm2 and attach to the substrate by tissue spreading (Tortolero-Langarica et al., 2020). Physical protection against coral predators increases survival and reduces predation effects (Hughes et al., 2007; Rivas et al., 2021), therefore it can be a potential tool to decrease mortality during the first growth phase, until outplants surpass a size that makes them less susceptible to predation and so increase their chances of long-term survival.

The lowest survivorship corresponds to P. lobata, which presents low dominance in the area, in contrast to coral reefs in the Central and South Pacific of Costa Rica (Cortés & Jiménez, 2003; Cortés et al., 2010; Jiménez, 2001). This might potentially indicate that local conditions at the restoration site are non-optimal for this species to prevail as a dominant reef-building coral. This situation contrasts with the high survivorship of Pocillopora spp. outplants, which used to be considered a highly sensitive genus to natural stressors (Glynn & Ault, 2000). However, they have recently proven to have the ability to acclimate to extreme conditions, especially thermal anomalies (Cruz-García et al., 2020; Romero-Torres et al., 2020) and upwelling conditions (Combillet et al., 2022). Due to their life history, it is expected that, in the short-term, Pocillopora spp. outplant survival will remain high, as colony size increases and competition for space and resources with other benthic fast-growing groups (e.g., macroalgae, turf) is reduced (Kodera et al., 2020; Lizcano-Sandoval et al., 2018; van Woesik et al., 2017).

Coral outplants in this study significantly increased their size in one year after their transplantation. Pocillopora spp. outplants experienced a 4-fold increase from their initial area in one year, while massive species showed a much slower growth: P. clavus and P. gigantea increased their initial area over 150 %, while P. lobata fragments did not even double their initial size. These differences between coral species respond to differences in their growth form, life history, local acclimatization, and reproduction strategies (Lirman & Schopmeyer, 2016; Page et al., 2018; Rinkevich, 2014). Pocillopora is a fast-growing genus, with growth rates over 5 cm yr-1 (Tortolero-Langarica et al., 2017), and its branching morphology exponentially increases the three-dimensionality of the colony, which translates to a high contribution to coral cover and reef complexity (Kodera et al., 2020; Tortolero-Langarica et al., 2019). In contrast, slow growth rates of massive species result in a short-term low contribution to coral cover and reef heterogeneity (Forsman et al., 2015; Page et al., 2018; Rivas et al., 2021). Pocillopora outplants showed a high growth rate of 9.98 ± 1.69 cm yr-1, in contrast to massive outplants, which not only showed low growth rates (0.61-1.48 cm yr-1), but also experienced partial tissue mortality during monitoring period. The high effectiveness observed using Pocillopora fragments has been key for it to be the most widely used genus for restoration efforts throughout the ETP (Combillet et al., 2022; Ishida-Castañeda et al., 2020; Liñán-Cabello et al., 2011; Lizcano-Sandoval et al., 2018). Nonetheless, in order to achieve ecological rehabilitation, it is important to consider not only structural complexity but the calcification rate and calcium carbonate production, which is mostly provided by massive species (Tortolero-Langarica et al., 2022). Therefore, efforts should be focused on new approaches and protocols that would allow to increase the survival of the so-far challenging massive corals, and hence scale and maximize restoration efforts.

Although the rapid growth of Pocillopora is the result of its life history, and even more so in the study area, where growth rates are naturally higher than in other localities in the ETP (Jiménez & Cortés, 2003), other factors that promote the survival and success of this genus should be considered. Coral growth is influenced by local and site-specific conditions (Foo & Asner, 2020; Foo & Asner, 2021; Kodera et al., 2020). Bahía Culebra is influenced by seasonal upwelling, with sudden drops in seawater temperature down to 19 °C, which may elicit coral bleaching (Cupul-Magaña & Calderón-Aguilera, 2008; Lirman et al., 2011), and compromise growth and reproduction due to lack of energy available, but generally cause low mortality (Rodríguez-Troncoso et al., 2014). The ability of corals to maintain their costly physiological processes like growth and reproduction under such conditions is an acclimatization response (Gerstle, 2020; Rodríguez-Troncoso et al., 2010; Rodríguez-Troncoso et al., 2014 ; Rodríguez-Troncoso et al., 2016), as is the differential effect of abnormal high and low-temperature bleaching. Heat-induced bleaching causes an expulsion of the symbiont -its main energy supplier-, but also damages the polyp, while in abnormally low temperature conditions, bleaching results from photoinhibition of the symbiont (Lough & van Oppen, 2018; van Oppen & Blackall, 2019). However, the coral maintains its physiological processes by obtaining heterotrophic energy, and thus may help compensate its diminished autotrophic capacities (Jiménez & Cortés, 2003; Ziegler et al., 2014), which may cause a decrease but not inhibition of growth. Therefore, corals in Bahía Culebra must have the ability to acclimate to intense and sudden decreases in temperatures occurring during upwelling season. Moreover, unlike for massive corals, the presence of herbivores is beneficial, as D. mexicanum acts as a biological controller for the main coral competitors such as macroalgae and turf (Alvarado et al., 2012, Alvarado et al., 2016), thus decreasing competition pressure and also, generating space for possible sexual recruits (Cano et al., 2021; Graham et al., 2015; Roth et al., 2018).

The lower growth rate exhibited by Pocillopora outplants in the first month after their outplanting could be a result of what has been previously described as “transplantation shock”. During this period, outplants undergo handling stress caused by the transplantation process (Precht, 2006), and acclimate to the environmental conditions of the new site; hence, their growth may be reduced (Afiq-Rosli et al., 2017; Forrester et al., 2012; Forrester et al., 2014; Lirman et al., 2010).

Our results show an influence of site of the donor colony on Pocillopora outplant growth. Differences in growth can be attributed to different genotypes and life history, even when outplanted to the same site (Drury et al., 2017; Goergen & Gilliam, 2018; Lirman et al., 2014; van Oppen et al., 2015). We do not possess information on every individual Pocillopora genotype outplanted to the reef; however, we hypothesize that the site of the donor colony could here be used as a proxy for different environmental tolerances, as fragments were originally collected from small areas in each donor site, and branching species reproduce mainly through fragmentation in the ETP (Bezy, 2009; Glynn et al., 2017; Sánchez-Noguera et al.; 2018b). Coral colonies from Matapalo site exhibited higher growth rates. Interestingly, this is the only site located outside the bay, is the most distant site from all others, and has relatively stable carbonate chemistry conditions (Sánchez-Noguera, 2019). Hence, the detected differences between donor sites when being subject to the same environmental conditions in the outplanting site could be a result of their life history and acclimation to the conditions of the donor site (Baums et al., 2019). Identifying growth differences between colonies and donor sites is relevant, even though trade-offs between growth, survival, resistance to disease, thermal tolerance and reproductive capacity may exist (Ware et al., 2020). Therefore, it is important to still outplant colonies with different life histories and responses to stress to the same restoration area, as this will maximize chances of survival in the face of changing conditions. Moreover, once outplants are sexually mature and reproduce among themselves, their offspring will likely receive considerable adaptive benefits (Baums et al., 2019), and hence ensure long-term success of restoration efforts.

As coral restoration is becoming a common strategy to recover and rehabilitate degraded coral reefs, it is essential to determine the best practices to ensure outplant survival and growth. These practices and techniques need to adapt to the local site-specific conditions for each area and outplanting site. Our results highlight the relevance of considering ecological processes such as herbivory and predation to maximize the success of restoration (Cano et al., 2021; Dang et al., 2020; Schopmeyer & Lirman, 2015) and how corals with different morphologies and life strategies may respond to the same environmental conditions. While Pocillopora spp. outplants had a positive response to outplanting technique and site conditions, fragments of massive species did experience partial tissue loss and dislodgement. Nevertheless, it is still important to restore coral reefs using a multi-species approach, since different coral species have different responses to disturbances (Lirman et al., 2011; Lustic et al., 2020). In the face of future changing conditions, promoting species richness and thus ecosystem resilience is key to ensure long-term recovery of coral reefs. Moreover, although monitoring individual outplants in the first year is vital to evaluate the feasibility of transplantation, there is a need to increase monitoring timeframes and develop appropriate ecological indicators in order to evaluate restoration effectiveness (Hein et al., 2017). These results could inform future practices and improve success of restoration efforts in the ETP.

Ethical statement: the authors declare that they all agree with this publication and made significant contributions; that there is no conflict of interest of any kind; and that we followed all pertinent ethical and legal procedures and requirements. All financial sources are fully and clearly stated in the acknowledgements section. A signed document has been filed in the journal archives.

uBio

uBio