Introduction

Organic products are broadly used by the global populationfor essential healthcare (Plantlife International, 2004; Grand View Research, 2018). In 2017 the market of personal-care products reached $12.19-billion, and further growth is foreseen (Grand view research, 2018). Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (MAPs) are a natural source of chemical substances that provide diverse biological properties (Bouyahya, Guaouguaou, Dakka, & Bakri, 2017). That is why countries several countries (i.e. the United States, Brazil, India, Colombia, and Cuba) support scientific research that let the discussion of the biological properties of MAPs and support better uses focused on bio-prospection (Tofiño-Rivera, Ortega-Cuadros, Melo-Ríos, & Mier-Giraldo, 2017).

Colombia has an outstanding floristic wealth, among which are included several promising MAPs of interest for science, such as Lippia alba (Mill.) N.E. Br, an aromatic species belonging to the Verbenaceae family, whose essential oils have been used in the cosmetic, food, and biomedical industries (Tofiño-Rivera et al., 2017; Linde, Colauto, Albertó, & Gazim, 2016) due to its biological properties. However, these properties are derived from the plant’s phytochemical composition. The presence and concentration of secondary metabolites is influenced by agro-economic management applied to the production of biomass, the phenological cycle of the material harvested, edaphoclimatic conditions, extraction method of the essential oil (Olivero-Verbel, González-Cervera, Güette-Fernandez, Jaramillo-Colorado, & Stashenko, 2010; Linde et al., 2016), and the evaluation technique employed in some cases (Ramírez & Castaño, 2009). This scoping review was conducted to identify the perspectives of the biotechnological application of essential oils (EO) of Lippia alba (Mill.) N.E. Br.

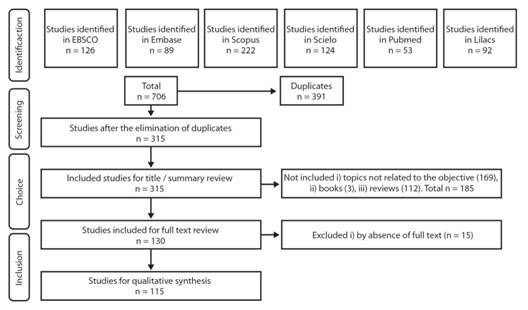

A scoping review (Armstrong, Hall, Doyle, & Waters, 2011) was carried out on the scientific literature that describes the biological activity of L. alba EO. Likewise, a search equation was elaborated by using the terms “Lippia alba andessential oil”, which was used to access published articles deposited in EBSCO, Embase, Pubmed, Scopus, SciELO, and Lilacs, since the beginning of time for each database, until October 8th, 2018. The registries recovered were filtered to eliminate duplicates using Zotero. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. A select group of documents was obtained to which a detailed analysis was applied (Fig. 1). The variables of interest (year, country, author, title, institution, EO extraction technique, biological activity evaluated, evaluation method, object of study, and result obtained) were extracted and compiled in a database using Microsoft Excel2016. IBM SPSS 23.0was used to conduct the statistical analyses.Application of the research protocol was conducted independently by two researchers to guarantee reproducibility of the work, and the discrepancies observed were solved through a third-party concept.

Bibliometric analysis: The search recovered 706 registries, from which 115 documents were analyzed (Fig. 1). It was identified that L. alba EO and their respective biological activity have been topics of interest in the scientific community since 1990. The publication of scientific articles has not been continuous. Countries with higher rate of published articles related with the subject are Brazil with 70 (60.5 %), Colombia with 29 (25.2 %), and India with 7 (6.2 %).The institutions that have led these investigations are Universidad Federal de Santa María with 18 (15.6 % publications), Universidad Industrial de Santander with 8 (6.9 % publications), Universidad de Cartagena with 6 (5.2 % publications), Universidade Regional do Cariri with 6 (5.2 % publications), and Universidade Federal da Bahía with 3 (2.6 % publications).

Fig. 1 Summary of the protocol of the exploratory systematic review applied and the respective results. Source: elaborated by the authors.

Biological activity ofL. albaessential oils: This exploratory review evidences the interest by the scientific community in progressing on the knowledge of the safe use of the derivates of these aromatic species. L. alba essential oils are antigenotoxic (Vera, Olivero, Jaramillo, & Stashenko, 2010; López, Stashenko, & Fuentes, 2011; Neira, Mantilla, Stashenko, & Escobar, 2018), but are toxic for Artemia franciscana, on which DL 6.17-24.87 μg/ml were presented (Olivero-Verbel, Güette-Fernandez, & Stashenko, 2009) and DL 50.4-21.05 µg/ml (Olivero-Verbel, González-Cervera et al., 2010). In mice, oral administration with dosages of 2 000 mg/kg is lethal; 900-1 500 mg/kg is life compatible but causes signs and symptoms of neurological damage and moderate to severe motor impairment as ataxia, lethargy, salivation, and transitory convulsions (Aular, Villamizar, Pérez, & Pérez, 2016). Intraperitoneal administration of dosages ≥ 1 500 mg/kg causes neurological damage, and dosages of 1 000 mg/kg cause slight hepatic damage (Olivero-Verbel, Guerrero-Castilla, & Stashenko 2010). On CHO cells, the oils did not inhibit cell proliferation at concentrations of 0.01-1 µg/ml (Tofiño-Rivera et al., 2016), with reports for VERO CC50 cells of 25.3-200 μg/ml (Meneses, Ocazionez, Martínez, & Stashenko, 2009; Escobar, Leal, Herrera, Martinez, & Stashenko, 2010; Moreno, Leal, Stashenko, & García, 2018; Zapata, Betancur-Galvis, Duran, & Stashenko, 2013), A549 CI50 47.80 μg/ml (Gomide et al., 2013), THP-1 CC50 16.8-43.17 µg/ml (Escobar et al., 2010; Neira et al., 2018), Jurkat CI50 16.6-31.6 μg/ml, HepG2 CI50 21.5-200 μg/ml (Zapata et al., 2013), and HeLa CI50 5-80.5 μg/ml (Agudelo-Gómez, Gómez, Durán, Stashenko, & Betancur-Galvis, 2010; Zapata et al., 2013).

L. alba is a species cultivated in different tropical, subtropical, and temperate zones throughout the world (Linde et al., 2016);its essential oils are promising due to their chemical diversity (Linde et al., 2016; Tofiño-Rivera et al., 2017). However, this chemical composition is sensibly dependent on the geographic location and the phenology of the plant material harvested (Durán, Monsalve, Martínez, & Stashenko, 2007), which has categorized L. alba in seven chemotypes (Table 1; Linde et al., 2016). Essential oils from chemotypes I and III plants present antispasmodic (Viana, Vale, Silva, & Matos, 2000; Blanco et al., 2013; Sousa et al., 2015; Silva et al., 2018; Carvalho et al., 2018),anticonvulsive (Fauth, Campos, Silveira, & Rao, 2002; Maynard et al., 2011), anxiolytic (Hatano, Torricelli, Giassi, Coslope, & Viana, 2012; Junior et al., 2018), and anti-inflammatory effects (Sepúlveda-Arias, Veloza, Escobar, Orozco, & Lopera, 2013). On contact with the skin, they are not irritating nor alter the histopathology (Neira et al., 2018), and are sleep enhancers (Fauth et al., 2002), anesthetic, and sedative (Salbego et al., 2017a). They also have antioxidant activity, although in this property the collection site is quite determining, given that chemotype I was a good antioxidant, while other chemotype III specimens had moderate and absent effect (Stashenko, Jaramillo, & Martínez, 2004; Olivero-Verbel, González-Cervera et al., 2010).

TABLE 1 L. alba chemotypes

| Chemotype | Description of the essential oil composition (principal constituent components) |

| I | Citral, linalool, β-Caryophylene (four subtypes within this chemotype) |

| II | Tagetenone |

| III | Limonene in large amounts and a variable amount of carvone or monoterpenic ketones instead of carvone |

| IV | Myrcene |

| V | γ-terpinen |

| VI | Canfora-1,8-cineole |

| VII | Estragole |

Source: elaborated by the authors.

Insecticide activity has been reported for chemotypes I and III; it was reported on Rhipicephalus microplus, RP50 0.47-5.07 mg/cm2 (Lima et al., 2016) and CL50 8.8-27 mg/ml (Peixoto et al., 2015b; Chagas et al., 2016), on Tribolium castaneum, RP 34-96 % in concentrations of 0.00002-0.2 μL/cm2 (Caballero-Gallardo, Olivero-Verbel, & Stashenko, 2011) and CL50 19.7-107.8 μL/ml, and on Sitophilus zeamais, CL50 15.2-70.8 μL/ml (Peixoto et al., 2015a). Chemotype III presents dissuasion > 80 % in oviposition of Aedes aegypti at concentrations of 0.005-0.2 µg/ml (Castillo, Stashenko, & Duque, 2017), and it also has larvicidal activity at variable concentrations: Vera et al. (2014) reported CI50 0.042-0.044 µg/ml and IC95 0.089-0.099 µg/ml; Muñoz, Stashenko and Ocampo (2014), CL50 0.11 µg/ml and CL99 0.211 µg/ml; Ríos, Stashenko and Duque (2017), CL50 63.61 - 72.34 µg/ml CL95 98.91-110.84 µg/ml; and Aldana and Cruz (2017), CL50 of 84-367 µg/ml and CL95 of 118-506 µg/ml.

Antiviral activity was not evidenced for chemotype I (Agudelo-Gómez et al., 2010), but chemotype III had preventive effect on cells infected with dengue virus (serotypes DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, DENV-4) (Ocazionez, Meneses, Torres, & Stashenko, 2010). The concentration of 11.1 μg/ml reduced the viral titers of the agent causing yellow fever (VFA) (Meneses et al., 2009), and concentrations of 125 and 250 µg/ml, at 24 and 48 h, respectively, reduced 101.5 log units the viral load of an HSV-1 isolate sensitive to Acyclovir (Agudelo-Gómez et al., 2010).

The amoebicidal activity of chemotype III was reported on Acanthamoeba polyphaga trophozoites with IC50 31.79 μg/ml (Santos et al., 2016b); leishmanicide activity on Leishmania braziliensis (promastigote CE50 8.88 µg/ml and amastigote CE50 9.19 µg/ml) and Leishmania chagasi (promastigote CI50 18.9 - 100 µg/ml) (Neira et al., 2018; Escobar et al., 2010). The trypanocidal effect is variable because for Trypanosoma cruzi,Moreno et al. (2018) determined that chemotype I had IC50 14.22 and 74 μg/ml on epimastigote, trypomastigote, and amastigote, while chemotype III had IC50 88.45 and > 150 μg/ml for the same parasite forms. For chemotype I, Escobar et al., (2010) obtained bio-activity on epimastigotes IC50 5.5-8.8 µg/ml, and amastigote IC50 12.2 - 17.47 µg/ml; and for chemotype III, epimastigote IC50 8.8 µg/ml and amastigote IC50 17.47 µg/ml. Additionally, Baldissera, Souza, Mourão, Silva, and Monteiro (2017) reported that under in-vitro conditions, concentrations of 0.5, 1, and 2 % of chemotype I had direct correlation with the efficacy in controlling Trypanosoma evansi, but under in-vivo conditions in mice; treatment with 1.5 ml Kg-1 did not show curative efficacy. Nematicidal activity of chemotypes I and III was reported on Meloidogyne incognita at concentrations from 0.1-2.5 ml/L, which had mean mortality percentages from 22 to 100 %, in dependent dosage; and diminished eclosion rate from 47 to 9 % (Moreira, Santos, & Innecco, 2009).

Antimicrobial and antifungal activity has been reported on periodontal-pathogenic microorganisms (Juiz et al., 2015; Bersan et al., 2014), cariogenic organisms (Bersan et al., 2014), enterobacteria (Pino, Ortega, Rosado, Rodríguez, & Baluja, 1996; Machado, Nogueira, Pereira, Sousa, & Batista, 2014), dermatophytes (Costa et al., 2014; Tangarife-Castaño et al., 2012), phytopathogens (Mena-Rodríguez, Ortega-Cuadros, Merini, Melo-Ríos, & Tofiño-Rivera, 2018; Anaruma et al., 2010), sulfate reductase (Souza et al., 2017a), important pathogens in aquiculture (Souza et al., 2017b; Majolo, Rocha, Chagas, Chaves, & Bizzo, 2017; Sutili et al., 2015), Candida albicans (Mesa-Arango et al., 2010; Santos et al., 2016a; Mesa-Arango et al., 2009), aspergillosis (Mesa-Arango et al., 2010; Glamočlija, Soković, Tešević, Linde, & Colauto, 2011; Mesa-Arango, et al., 2009), Cryptococcosis (Santos et al., 2016a); gastrointestinal, cutaneous, and nosocomial infections (Pino et al., 1996; Machado et al., 2014; Porfírio et al., 2017); under the MIC interval between 4.0-9 370 µg/ml and MBC 6.5-2 500 µg/ml for bacteria (Table 2), and MIC 31.25-2 000 and MBC/MFC 500-1 250 µg/ml for fungus (Table 3).

TABLE 2 Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericide concentration (MBC) of chemotypes I and III essential oils on bacterial species

| Microorganism | Strain/isolate | MIC (µg/ml) | MBC (µg/ml) | Chemotype | Reference |

| Aeromonas spp. | Isolates, ATCC 7966 | 2862 - 5.000 | 781.3 - 6.000 | I | (Sutili et al., 2015; Majolo et al., 2017; Souza, Costa et al., 2017) |

| Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans | ATCC 43717 | >3 200 | >3 200 | III | (Juiz et al., 2015) |

| Bacillus subtilis | ATCC 7001 | 630 | 1.250 | III | (Pino et al., 1996) |

| Bacteroides fragilis | ATCC 25285 | 400 - 1 600 | 400 -1 600 | III | (Juiz et al., 2015) |

| Desulfovibrio alaskensis | NCIMB 13491 | 78 - 2 500 | I | (Souza, Goulart et al., 2017) | |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | ATCC 13088 | 2 500 | 2 500 | III | (Pino et al., 1996) |

| Enterococcus faecalis | ATCC 19433 | 630 - 4 000 | 1 250 | I and III | (Pino et al., 1996; Santos et al., 2016a) |

| Escherichia coli | ATCC 25922, 201389, 10536, Isolates | 400 - 4 000 | 2 500 - 1 170 | I and III | (Pino et al., 1996; Duarte et al., 2007; Machado et al., 2014; Santos et al., 2016a) |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | ATCC 25586 | 125 | 125 | I | (Bersan et al., 2014) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | ATCC 13883 | 2 500 | 2 500 | III | (Pino et al., 1996) |

| Listeria innocua | ATCC 19115 | 580 - 1 330 | 1 330 - 1 170 | I | (Machado et al., 2014) |

| Listeria monocytogenes | ATCC 33090 | 580 - 1 330 | 580 - 1 330 | I | (Machado et al., 2014) |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | ATCC 33277 | 6.5 - 250 | 6.5 - 250 | I and III | (Bersan et al., 2014; Juiz et al., 2015) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ATCC 9027 | 5 340 - 9 370 | 5 340 - 9 370 | I | (Machado et al., 2014) |

| Salmonella choleraesuis | ATCC 10708 | 5 340 - 9 370 | 5 340 - 9 370 | I | (Machado et al., 2014) |

| Serratia marcescens | ATCC 8100, MBCAI 469 | 630 -4 000 | 1 250 | I and III | (Pino et al., 1996; Santos et al., 2016a) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | ATCC 6538, ATCC 25923 | 290 -1 000 | 290 -2 000 | I and III | (Pino et al., 1996; Machado et al., 2014; Porfírio et al., 2017) |

| Streptococcus mitis | ATCC 903 | 250 | - | I | (Bersan et al., 2014) |

| Streptococcus sanguis | ATCC 10556 | 250 | 100 000 | I | (Bersan et al., 2014) |

Source: elaborated by the authors.

TABLE 3 Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum fungicide concentration (MFC), of chemotypes I and III essential oils on fungal species

| Microorganism | Strain/isolate | MIC (µg/ml) | MFC (µg/ml) | Chemotype | Reference |

| Aspergillus flavus | ATCC 204304 | 180 - 1 600 | - | I and III | (Mesa-Arango et al., 2009; Mesa-Arango et al., 2010) |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | ATCC 204305, ATCC9142 | 35 - 570 | 1250 | I and III | (Mesa-Arango et al., 2009; Mesa-Arango et al., 2010; Glamočlija et al., 2011) |

| Aspergillus niger | ATCC6275 | 600 | 600 | I | (Glamočlija et al., 2011) |

| Aspergillus ochraceus | ATCC12066 | 300 | 600 | I | (Glamočlija et al., 2011) |

| Aspergillus versicolor | ATCC11730 | 300 | 600 | I | (Glamočlija et al., 2011) |

| Candida albicans | MBCAI 560, ATCC 10231, CBS 562 | 250 - 2 000 | 500 | I | (Duarte, Figueira, Sartoratto, Rehder, & Delarmelina, 2005; Bersan et al., 2014; Santos et al., 2016a) |

| Candida dubliniensis | ATCC 7978 | 500 | - | I | (Santos et al., 2016a) |

| Candida glabrata | ATCC 90030 | 2 000 | - | I | (Santos, 2016a) |

| Candida krusei | ATCC 6258, clinical isolate | 140 - 2 000 | - | I and III | (Mesa-Arango et al., 2009; Mesa-Arango et al., 2010; Santos et al., 2016a) |

| Candida parapsilosis | ATCC 22019, clinical isolate | 280 - 2 000 | - | I and III | (Mesa-Arango et al., 2009; Mesa-Arango et al., 2010; Santos, 2016a) |

| Candida tropicalis | ATCC 13803 | 2 000 | - | I | (Santos et al., 2016a) |

| Colletotrichum gloeosporioides | Isolates | 300 - 900 | - | I | (Anaruma et al., 2010; Mena-Rodríguez et al., 2018) |

| Cryptococcus gattii | ATCC MYA-4560, MYA-4563, ATCC 208821 | 1 000 - 2 000 | - | I | (Santos et al., 2016a) |

| Cryptococcus grubii | ATCC 208821 | 1 000 | - | I | (Santos et al., 2016a) |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | ATCC MYA-4560 | 1 000 | - | I | (Santos et al., 2016a) |

| Fusarium oxysporum | ATCC 48112 | >500 | - | I and III | (Tangarife-Castaño et al., 2012) |

| Macrophomina phaseolina | Isolates | 800 - 1 200 | - | I | (Mena-Rodríguez et al., 2018) |

| Microsporum gypseum | Human isolates | 156 | - | I | (Costa et al., 2014) |

| Penicillium funiculosum | ATCC10509 | 1 250 | 1 250 | I | (Glamočlija et al., 2011) |

| Penicillium ochrochloron | ATCC9112 | 600 | 1 250 | I | (Glamočlija et al., 2011) |

| Phytophthora capsici | Isolates | 50 - 150 | - | I | (Mena-Rodríguez et al., 2018) |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | ATCC MYA-4567 | 2 000 | - | I | (Santos et al., 2016a) |

| Trichoderma viride | ATCC5061 | 600 | 1 250 | I | (Glamočlija et al., 2011) |

| Trichophyton mentagrophytes | ATCC 24198 | 125 - 500 | - | I and III | (Tangarife-Castaño et al., 2012) |

| Trichophyton rubrum | ATCC 28188, human isolates | 31.25 - 354.98 | - | I and III | (Tangarife-Castaño et al., 2012; Costa et al., 2014) |

Source: elaborated by the authors.

Final considerations: L. alba is promising plant in Latin America (Tofiño-Rivera et al., 2017), which is included in the Colombian Vademecum of Medicinal Plants (Ministry of Health and Social Protection [MinSalud], 2008), and is approved for over-the-counter sale as antiseptic for external use and adjuvant in the treatment of anxiety of nervous origin in humans (INVIMA, 2018). According to the records found, L. alba essential oils are bio-inputs of interest, given their possibility of bio-prospection. In biomedical sciences, research has provided effective tools to solve problems related with amoebic infections (Santos et al., 2016b), herpetic infections (Agudelo-Gómez et al., 2010), tropical diseases e.g. like dengue (Ocazionez et al., 2010), leishmaniasis (Escobar et al., 2010; Neira et al., 2018), trypanosomiasis (Escobar et al., 2010; Baldissera et al. 2017; Moreno et al., 2018), and yellow fever (Meneses et al., 2009), control of vectors, like Aedes aegypti (Vera et al., 2014; Castillo et al., 2017; Ríos et al., 2017; Aldana & Cruz, 2017), mycosis (Mesa-Arango et al., 2010; Santos et al., 2016a; Glamočlija et al., 2011), in-hospital diseases (Santos et al., 2016a; Pino et al., 1996; Machado et al., 2014), and diseases related with the oral cavity (Juiz et al., 2015; Bersan et al., 2014).

In addition, the agroindustrial sector has focused on the use of L. Alba EO to control efficiently parasites that affect vegetable production (Moreira et al., 2009), improve grain conservation (Caballero-Gallardo et al., 2011; Peixoto et al., 2015a; Shukla, Kumar, Singh, & Dubey, 2009), improve the quality of products derived from livestock (Peixoto et al., 2015b; Lima et al., 2016; Chagas et al., 2016), as well as diminish damage during transport of ornamental aquatic species, like Hippocampus reidi (Cunha et al., 2011); anesthetics for model organisms, like Hypsiboas geographicus (Salbego et al., 2017a); sedatives, anesthetics, and preservatives in hedgehogs (Simões et al., 2017) and shrimp (Parodi et al., 2012), and fish of economic importance (Sena et al., 2016; Hohlenwerger et al., 2017; Cunha et al., 2010).

In aquiculture, for L. alba essential oils, chemotype I has reported promising results, given their sedative effect on Rhamdia quelen (20-40 μL/L) (Salbego et al., 2017b; Veeck et al., 2018); anesthetic effect on Litopenaeus vannamei (> 30 μL/L) (Parodi et al., 2012), Colossoma macropomum (62,5-375 μL/L) (Batista et al., 2018), Echinometra lucunter (150 μL/L) (Simões et al., 2017), Rhamdia quelen (20 and 150-450 μL/L) (Cunha et al., 2010; Toni et al., 2014; Veit et al., 2017; Salbego et al., 2017b), Argyrosomus regius (200 μL/L) (Cárdenas et al., 2016), Serrasalmus rombeus (50-200 μL/L) (Almeida, Heinzmann, Val, & Baldisserotto, 2018), Sparus aurata (100-300 μL/L) (Toni et al., 2015); and reduce stress in Rhamdia quelen (10 - 40 μL/L) (Azambuja et al., 2011; Veeck et al., 2013), Oreochromis niloticus (20 μL/L) (Hohlenwerger et al., 2017), Litopenaeus vannamei (> 30 μL/L) (Parodi et al., 2012), Echinometra lucunter (150 μL/L) (Simões et al., 2017), and tambacu hybrids (Piaractus mesopotamicus × Colossoma macropomum) (200 μL/L) (Sena et al., 2016).

Chemotype I EO can be used to enhance aquaculture techniques because they maintain the freshness of fish stored in ice (Veeck et al., 2018), do not modify the organoleptic characteristics (Cunha et al., 2010; Toni et al., 2014; Hohlenwerger et al., 2017), or affect fish quality (Sena et al., 2016). However, further studies are needed, given that Veeck et al. (2018) reported that concentrations from 30-40 µl/L do not represent antimicrobial activity against mesophiles and psychrophiles, and Veit et al. (2017) obtained that 375 ml/L do not prevent physico-chemical changes produced by the electric stunning or hypothermia in fillets of Rhamdia quelen during frozen storage. Some important recommendations have been considered: 1) to transport live fish, 15 μL/L of essential oil for Argyrosomus regius, or 100-300 μL/L for Sparus aurata, or 62.5-375 μL/L for Colossoma macropomum are not recommended because these do not prevent the response to stress (Toni et al., 2015; Cárdenas et al., 2016; Batista et al., 2018); 2) prior sedation is not recommended with 200 µL/L during three minutes with L. alba E Oto reduce initial agitation, nor is treatment recommended with 30-40 µL/L EO for transport because it does not avoid oxidative stress in liver (Salbego et al., 2014); for Argyrosomus regius, 15 μL/L is not recommended to transport live fish, given that it does not inhibit stress (Cárdenas et al., 2016); 3) concentrations of 1 600 and 3 200 μL/L of chemotype III oils are effective against Anacanthorus spathulatus, Notozothecium janauachensis, and Mymarothecium boegeri, natural parasites of Colossoma macropomum; but these dosages are toxic to fish gills, therefore, there is a need to propose strategies to take advantage of the antihelmintic effect of these products without affecting the host organism, using cutting-edge biotechnological techniques, like nanotechnology (Soares et al., 2016).

Chemotypes I and III seem to be the most common. Chemotype I has more reports on the biological effect; however, it must be considered that the cell and molecular characteristics of each microorganism or organism also interfere with the EO spectrum, given that on Tribolium castaneum and Sitophilus zeamais parasites, chemotype III was more effective than chemotype I (Peixoton et al., 2015a), but on Candida krusei and Aspergillus fumigatus, chemotype I was more effective (Mesa-Arango, et al., 2009). Additionally, chemotype I had anesthetic effect on Hypsiboas geographicus (Salbego et al., 2017a), but not on Neohelice granulata (Souza et al., 2018), and chemotype III was anti-inflammatory in the RAW 264.7 murine cell line (Sepúlveda-Arias et al., 2013), but this effect was not registered on Oreochromis niloticus (Rodrigues-Soares et al., 2018).

One of the critical variables associated with energizing an industry through L. alba EO corresponds to the phytochemical characterization of the plant material from which it is extracted, given that the availability of raw material with standardized conditions constitutes a critical point for the bio-industry (BIOinTropic, Universidad EAFIT, & Silo, 2018). We can highlight the lack of a comprehensive productive model for the agroindustrial use of L. alba because only specific studies are identified on a single management practice and for a specific area of the country (Zambrano, Buitrago, Durán, Sánchez, & Bonilla, 2013).

Regarding this work, it was found that 18.3 % of the articles did not relate the biological activity of the EO with its composition, given that no indication is provided of the chemotype or majority components. In this sense, under a general vision of the registries recovered, exploratory or preliminary works were observed without the continuity of the evaluation, according to the Colombian technical standards and norms by the WHO to advance in the formulation of bio-products (WorWHO, 2004; ICONTEC, 2011), which is reflected in the lack of patents registered or pending, although research groups exist in Colombia that include L. alba as study model (Tofiño-Rivera et al., 2017). A vector and confluent effort as a country is needed here through strategies defined within the National Agricultural Innovation System (SNIA, for the term in Spanish) to encourage development based on bio-economy and, thus, take advantage of the diversity of L. alba chemotypes registered throughout the country -citral in Bolívar and Cesar, limonene in Arauca, and carvone in Cundinamarca, Tolima, Boyacá, Valle del Cauca, Santander, Antioquia, Quindío, and Cesar (Durán et al., 2007; Mesa-Arango et al., 2009; Olivero-Verbel, Guerrero-Castilla et al., 2010; Tofiño-Rivera et al., 2016)-, considering the specific uses referred by the scientific literature and which have been systematized in this document.

Unlike synthetic substances (Célis, 2018) and other natural standardized substances in which the concentration used over the same or different organisms will permit a meta-analysis for a finer verification of the biological effect of the substance in context (Valero et al., 2011), this possibility would not be rigorous in the case of the set of documents recovered in this research on the biological activity of L. alba EO because although many of the investigations refer to the chemotype or the majority component, the same concentration of EO, or the same chemotype, may have large variations in the concentrations of its majority or minority components. This variation is dependent on the equation that explains the phenotypic expression of an attribute F = G + A + GXA: chemotype -genetics G-, bioclimatic offer of the plantation -A-, and the genotype x environment interaction -GXA-, which are conditioners of the plant’s physiological response over the secondary metabolism, upon the bioclimatic offer, agro-economic management, and harvest time (Palacio-López & Rodríguez-López, 2008). In addition to this heterogeneity exhibited by the raw material, the extraction method also affects the final composition of the EO, which hinders the possibility for a meta-analysis for the bioactivity of L. alba from a set of studies with high variability in the concentrations of the bioactive components of the EO (Durán et al., 2007; García-Perdomo, 2015; Barrientos, Reina, & Chacón, 2012; Delgado, Sánchez, & Bonilla, 2016). It would, then, be important to have a set of studies with detailed phyto-chemistry of the EO and which use the individual standardized bioactive components as controls (Ortega-Cuadros, Tofiño-Rivera, Merini, & Martinez-Pabón, 2018). Other exploratory revision works have registered the variable biological activity of the L. alba EO, specifically in the results of microbial control, dependent on the extraction technique used and the quality of biomass harvested. This work also highlighted high heterogeneity in assessment techniques of the biological activity of the L. alba EO used by the scientific community (Ortega-Cuadros & Tofiño-Rivera, 2019).

It is concluded that L. alba EO is a substance of broad spectrum of use, which is why industrial development is feasible based on this raw material. Nevertheless, it is necessary to establish within the SNIA research programs that prioritize the most consistent effects registered in this review, in accordance with national and global demands. Besides, progress is necessary on preliminary tests at pilot scale established by the Colombian norms to advance in the generation of commercial formulations. One of the first steps in this respect corresponds to the methodological harmonization, given that in some studies there was no appropriate control of the variables interfering on the biological quality of the L. alba EO, no detailed phyto-chemical analyses were presented, nor were adequate controls involved to facilitate a subsequent meta-analysis that guides the prioritizing of investment resources in the most consistent application lines. Another significant element is the generation of strategic alliances to elaborate protocols to standardize agro-economic management conditions of the plants in production zones, as well as articulation with the industry for scaling of the protocols formulated.

Ethical statement: authors declare that they all agree with this publication and made significant contributions; that there is no conflict of interest of any kind; and that we followed all pertinent ethical and legal procedures and requirements. All financial sources are fully and clearly stated in the acknowledgements section. A signed document has been filed in the journal archives.

Supplementary material

Acronym definition: MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration; MBC: minimum bactericide concentration; LD50: lethal dosage 50; LD or LC: lethal dosage or lethal concentration; IC50: minimum inhibition concentration 50; CC50: cytotoxic concentration 50; EC50: effective concentration 50; RP50: repellency 50; RP: repellency percentage; CHO: Chinese hamster ovary cells; VERO: African green monkey kidney; A549: human lung carcinoma cell line; THP-1: human leukemic monocyte cells; Jurkat: T-cell lymphocytes with acute lymphoid leukemia; HepG2: hepatocellular liver cells; HeLa: human cervical epithelial carcinoma.

uBio

uBio