Revista de Biología Tropical

versión On-line ISSN 0034-7744versión impresa ISSN 0034-7744

Rev. biol. trop vol.56 no.1 San José mar. 2008

Jonathan Herrera-Vásquez1, William Bussing1 & Federico Villalobos2

1 Museo de Zoología, Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica; jonnabio@gmail.com; jonnathan@biologia.ucr.ac.cr; wbussing@biologia.ucr.ac.cr

2 Instituto de Investigaciones Científicas y Tecnológicas, San José, Costa Rica; fvillalo@gmail.com

Abstract: Track analysis and Parsimony analysis of endemicity (PAE) were performed to analyze the distribution pattern of Costa Rican freshwater fishes. A basic matrix (presence/absence) was prepared using the distribution of 77 freshwater fish. The data were analyzed with CLIQUE software in order to find generalized tracks (cliques). Data also were analyzed with the software NONA and Winclada version 1.00.08 in order to perform the Parsimony Analysis of Endemicity (PAE). Fourteen equally probable cliques were found with 31 species in each and the intersection of the amount was selected as a generalized track dividing the country in two main zones: Atlantic slope from Matina to Lake Nicaragua and Pacific slope from the Coto River to the basin of the Tempisque River connected with some branches oriented to the central part of the country. PAE analysis found ten cladogram areas (72 steps, CI=0.45, RI=0.64), using the "strict consensus option" two grouping zones were identified: Atlantic slope and Pacific slope. Both PAE and Track Analysis show the division of the two slopes and the orientation of the generalized track suggests new biogeographical evidence on the influence of both old and new southern elements to explain the migrations of freshwater fish into Central America during two different geological events. Rev. Biol. Trop. 56 (1): 165-170. Epub 2008 March 31.

Key words: freshwater fishes, biogeography, PAE, Track Analysis, panbiogeography, Costa Rica.

Costa Rica, whose territory comprises 52 100 km2 (0.03 % of the total surface of the planet), possesses about 5 % of the total diversity described thus far in the world. This diversity includes 135 freshwater fish species (19 endemic) of 350 reported for Mesoamerica, which extends from Tehuantepec isthmus in the south of Mexico as far as northern Colombia. Moreover three of the four ichthyic Mesoamerican provinces converge in Costa Rica: Chiapas-Nicaragua and Isthmian in the Pacific slope and San Juan in the Atlantic slope (Bussing 1976, 1985, 2002).

Costa Ricas continental ichthyofauna possesses a geographical distribution influenced by both northern continent and principally the southern continent. Bussing (1985) and Briggs (1994) argue that the colonization of the Central American families Characidae, Pimelodidae, Poecilidae and Cichlidae, occurred during the Cretaceous/Paleocene, 60 million years ago, a period in which the existence of the old connection permitted the dispersion of the South American species. This connection disappeared during the Tertiary, Central Americas separation from South America permitted the development of endemic lineages (Bussing 1976). Finally a new connection appeared by the Pliocene (Pitman et al. 1993), allowing a new dispersion through Central America.

Few studies have been made on the distribution, systematics and biogeography of middle American Cichlids (Bussing 1985, Bussing 2002, Roe et al. 1997, Martin and Birmingham 1998). The capacity of track analysis to find relationships among ancestral biota given a panbiogeographical approach that emphasizes the spatial and geographical dimension of biodiversity is an important tool in order to begin the identification of evolutionary processes. Roe et al. (1997), and Martin and Birmingham (1998) contributed with molecular and ecological information, which is a good initiative in order to comprise the biogeography and evolutionary history of Mesoamerican freshwater fish. Given the necessity for knowledge in this area and on features in Costa Rica, we consider it useful to contribute new biogeographical evidence utilizing Track Analysis and Parsimony Analysis of Endemicity (PAE) evaluate the distribution of the Costa Rican freshwater fish.

Materials and methods

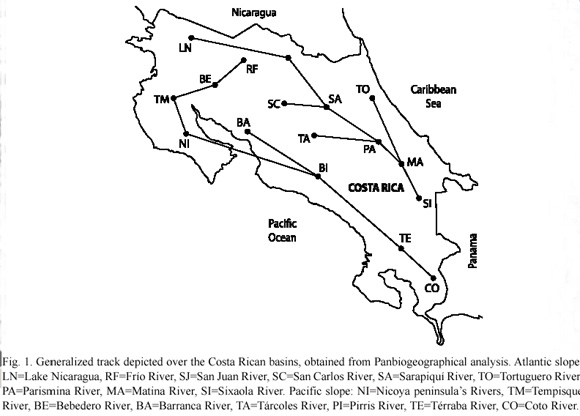

In order to make the analyses, information about distribution of 77 freshwater fishes species was extracted from a data base available in the Zoological Museum of the University of Costa Rica (Table 1). The information utilized corresponds to six more diverse families: Cichlidae (24 sp.), Poecilidae (20 sp.) Characidae (17 sp.), Eleotridae (9 sp.), Pimelodidae (5 sp.) and Ariidae (2 sp.). Area was defined according to 17 basins established by Bussing (2002) (Fig. 1): Atlantic slope: LN=Lago de Nicaragua, RF=Río Frío, SJ=Río San Juan, SC=Río San Carlos, SA=Río Sarapiquí, TO=Río Tortuguero, PA=Río Parismina, MA=Río Matina, SI=Río Sixaola. Pacific slope: NI=Rivers on the Península de Nicoya, TM=Río Tempisque, BE=Río Bebedero, BA=Río Barranca, TA=Río Tárcoles, PI=Río Pirris, TE=Río Grande de Térraba, CO=Río Coto. Of 19 endemic species reported to Costa Rica 15 were utilized in the analysis (Table 1).

In order to perform the Track Analysis (Craw 1989) a basic matrix of taxa/area was constructed (presence coded "1" and absence coded "0") (Table 2) and analyzed using the Clique-compatibility software (Felsenstein 1986). The total number of cliques (tracks) was determined and the longest was established as a generalized track and drawn by using a minimal spanning tree method.

Parsimony Analysis of Endemicity was performed according to Morrone (1994), utilizing the basins previously established as geographical operators. A hypothetical ancestral area coded with zero to all characters was included to root the tree. The matrix was analyzed using the software NONA (Goloboff 1993) and Winclada version 1.00. 08 (Nixon 1999).

Results

A total of 14 equally probable cliques containing 31 species were obtained. The intersection of the amount resulting the species was selected as generalized track: Aequidens coeruleopunctatus, Amphilophus lyonsi, Archocentrus myrnae, A. sajica, A. septemfasciatus, Astatheros altifrons, A. bussingi, A. diquis, A. rhytisma, Brachyrhaphis olomina, Pallichthys quadripunctatus, P. tico, Pallichthys amates, Poecilia gillii, P. mexicana, Poeciliopsis paucinmaculata, P. turrubarensis, Priapichthys annectens, P. panamensis, Pseudocheirodon terrabae, Bramocharax bransfordii, Pterobrycon myrnae, Astyanax nasutus, A. aeneus, Brycon guatemalensis, Bryconamericus terrabensis, Hyphesobrycon panamensis, Pimelodella chagresi, Dormitator latifrons, Dormitator maculatus and Eleotris amblyopsis. Fig. 1 depicts two regions of spatial homology, one in the Atlantic slope from the southern part of the country to Lake Nicaragua and the other on the Pacific slope from the basin of Coto River to Tempisque River basin, which is connected with Frío River basin and some bifurcations toward the central region of the country.

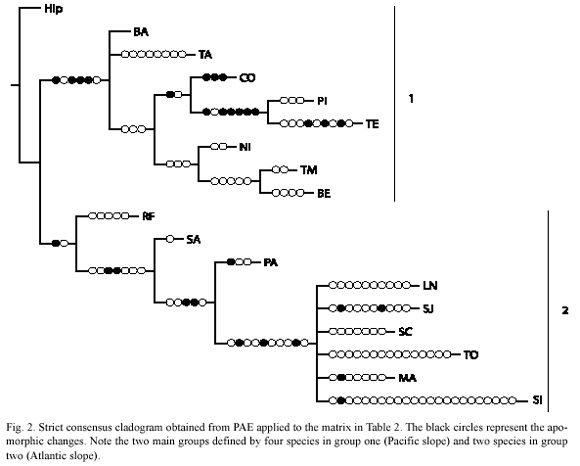

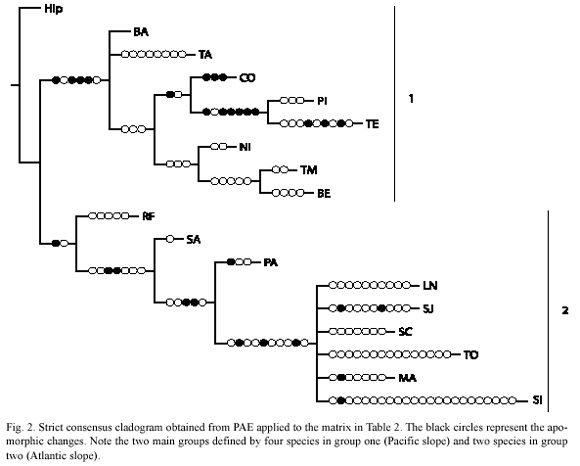

PAE put forward a total of ten area cladograms, strict consensus obtained with 72 steps, CI=0.45 and RI=0.64 (Fig. 2). Two main groups were identified one of them containing four species: Theraps sieboldii, Poeciliopsis turrubarensis, Arius seemanni and Dormitator latifrons, and including the basins BA, TA, CO, PI, TE, BE, TM, NI. The second group was defined by two species Theraps underwoodi and Brachyrhaphis holdridgei, including the basins SA, PA, SI, MA, TO, SJ, LN, and SC (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Empirical observations of the current distribution of the Central American freshwater fish showed two main groups with distinct spatial and temporal origins (Bussing 1976, 1985). The old northern element presents a major quantity of species in the Atlantic slope and some representatives in the Pacific slope (e.g. Astyanax, Poecilia, Priapichthys, Neoheterandria, Amphilophus, Archocentrus, and Astatheros). In contrast, the new southern element has a major quantity of species in the Pacific slope (e.g. Pterobrycon, Nannorhamdia, Brycon, Roeboides, Pseudocheirodon) which is reflected in the track analysis with two main tracks, one in the Pacific and other in the Atlantic slope, separated at the south of the country by the Talamanca mountain range.

With PAE the separation of two slopes was also observed (Fig. 2), and seven of fifteen endemic species utilized were found in the Isthmian province. Therefore the influence of a new southern element after Pliocene with regard to genera composition and distribution (Bussing 1985) was corroborated in light of our analysis. In fact, the Terraba and Pirris basins form an endemic area within the Isthmian province due to the number of endemic species (Fig. 2).

Lundberg (1993) reported fossil cichlids (located in the old genus Cichlasoma) found in the Antilleans and dated to the early Miocene when the Caribbean islands were possibly formed from Central America. Given the physiological characteristics of this family, tolerant to salinity (secondary type), it is presumed that cichlids were among the first inmigrants from the southern continent as revealed in the appearance of the old southern element. Later vicariant events and the reestablishment of the isthmus (Bussing 1985), originate different lineages of the new southern element.

In conclusion, both PAE and track analysis illustrate the separation of two slopes. The orientation of the generalized track suggests new biogeographical evidence about the influence of both old and new southern elements, and the aggregation pattern found with PAE suggests inmigration associated with different geological periods. More detailed analyses are needed in order to solve cladistic biogeography problems related to Costa Rica and Central Americas freshwater fishes.

Resumen

Con el objetivo de analizar el patrón de distribución de peces de agua dulce de Costa Rica se aplicó un análisis de trazos y de parsimonía de endemismos (PAE). Se construyó una matriz básica utilizando la distribución de 77 especies. Se utilizó el programa CLIQUE con la intención de encontrar los trazos generalizados y NONA y Winclada, versión 1.00.08, con el fin de llevar a cabo el PAE. Se encontró un total de 14 cliques igualmente probables con 31 especies. De esta cantidad se construyó un trazo generalizado que constituye la intersección del total, dividiendo el país en dos zonas: Atlántico, desde Matina hasta el Lago de Nicaragua y Pacífico desde el río Coto hasta el río Tempisque conectado con la región central del país. El PAE encontró diez cladogramas de áreas (72 pasos, CI=0.45, RI=0.64), cuyo consenso estricto identificó dos zonas de agrupamiento: Atlántico y Pacífico. Ambos análisis muestran la división entre las dos vertientes y la orientación de los trazos generalizados sugiere nueva evidencia de la influencia biogeográfica de los denominados elementos de migración antiguo y nuevo del sur, los cuales se habían sugerido empíricamente en el pasado para explicar las migraciones hacia Centroamérica en dos periodos geológicos diferentes.

Palabras clave: peces de agua dulce, biogeografía, PAE, análisis de trazos, Panbiogeografía, Costa Rica.

References

Bussing, W.A. 1976. Geographic distribution of the San Juan ichthyofauna of Central America with remarks on its origin and ecology, p. 103. In T.B. Thorson (ed.). Investigations of the ichthyofauna of Nicaraguan lakes. University of Nebraska, Nebraska, USA. [ Links ]

Bussing, W.A. 1985. Patterns of distribution of the Central American ichthyofauna, p. 453-473. In F.G. Stheli & S.D. Webb. The great American interchange. Plenum, New York, USA. [ Links ]

Bussing, W.A. 2002. Freshwater fishes of Costa Rica. Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica. [ Links ]

Briggs, J. 1994. The genesis of Central America: biology versus geophysics. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 4: 169-172. [ Links ]

Craw, R.C. 1988. Continuing the synthesis between panbiogeography, phylogenetic systematics and geology as illustrated by empirical studies on the biogeography of the New Zealand and the Chatham Islands. Syst. Zool. 37: 291-310. [ Links ]

Felsenstein, J. 1986. Clique compatibility program, PHYLIP. University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA. [ Links ]

Goloboff, P.A. 1993. NONA v. 1.1. Inst. Miguel Lillo, Tucumán, Argentina. [ Links ]

Lundberg, J.G. 1993. African-South American freshwater fish Clades and continental drift: problems with a paradigm, p. 156-199 In P. Goldblatt (ed.). The biotic relationships between Africa and South America. Yale, New York, USA. [ Links ]

Martin, A.P. & E. Birmingham. 1998. Systematics and evolution of lower Central American Cichlids inferred from analysis of cytochrome b gene sequences. Mol. Phy. Evol. 9: 192-203. [ Links ]

Morrone, J.J. 1994. On the identification of areas of endemism. Syst. Biol. 43: 438-441. [ Links ]

Nixon, K.C. 1999. Winclada v.0.9.99 v. beta. University of Ithaca, New York, USA. [ Links ]

Pitman, W.C., S. Cande, J. LaBrecque & J. Pindell. 1993. Fragmentation of Gondwana: the separation of Africa and South America, p. 15-34. In P. Goldblatt (ed.). Biological relationships between Africa and South America, Yale, New York, USA. [ Links ]

Roe, J.K., D. Conkel & C. Lydeard. 1997. Molecular systematics of Middle American cichlid fishes and the evolution of trophic-types in Cichlasoma (Amphilophus) and C. (Thorichthys). Mol. Phy. Evol. 7: 366-376. [ Links ]

uBio

uBio