Introduction

Throughout history, language contact has always existed and, due to globalisation, this contact between languages is becoming more prevalent thereby producing a greater impact on speakers. This impact, in turn, led to different kind of linguistic phenomena such as interference, language shift, language loss or attrition.

Studies on the maintenance or loss of languages and cultures have been well documented. Just to mention a few, Huffines (1980) indicated that a relative isolation of Germans in Pennsylvania was taking place; De Bot & Fase (1991) also studied the position of the first-generation migrant worker groups in Western Europe. In a similar vein, Guardado (2002) reflected on the loss and maintenance of first language in Hispanic families in Vancouver and, besides that, literature on attrition is extensive (cf. Ben-Rafael & Schmid, 2007; Hansen, 2001; Köpke & Schmid, 2004; Köpke et al., 2007; Lambert & Freed, 1982; Schmid & Dusseldorp, 2010; Yilmaz & Schmid, 2012).

Albeit attrition itself is not the main purpose of this article, it seems necessary to draw attention to it in order to understand correctly this research. Relying on the definitions explained by different authors through the times (Ammerlaan, 1996; Andersen, 1982; Kaufman, 1991; Köpke & Schmid, 2004; Pavlenko, 2000; Olshtain & Barzilay, 1991; Schmid, 2008 y 2011; Schmid & Dusseldorp, 2010; Schmid & Köpke, 2009), we would define attrition as a sociolinguistic phenomenon which consists of the loss of a portion of mother tongue, the deterioration of mother tongue in migrants or just the perception of it.

Immigration in Spain is not on the same signal path as the previously mentioned countries (Canada or United States) since for Spain, immigration represented a new emerging reality to cope with. Spain has moved recently from being a country of emigration to being a country of immigration and its situation regarding migration has drastically changed. Around two million Spanish left the country from 1960 to 1975; nevertheless, during 1980s, a strong economic growth made Spain to be chosen by many immigrants. In 2000 and without taking into account the undocumented, around one million immigrants were registered (Kreienbrik, 2008).

Immigrants have always been branded as minorities living isolated from the rest of the population, gathering together, and following their customs and language. However, Blanken et al. (1993) posited that when an immigrant moves to another country, he has a “passive knowledge” of his mother tongue. If he or she spends little time without using it the activation threshold will be low whereas the most time without speaking, the most activation needed in order for the language to be activated. In the same line, according to Köpke (2004), knowledge is kept in the long-term memory (LTM) and if this information is not activated frequently, it could be forgotten.

This would lead us to wonder if a possible relationship may result between vocabulary and the language use, thus this article will center on the vocabulary performance of immigrants in Spain. Vocabulary and attrition are believed to be closely intertwined since lexical access and fluency are identified as the most vulnerable areas in attrition, more than syntax (Gürel, 2004; Köpke, 2002; Montrul, 2002). That is the reason, the article will conclude with a simple but fundamental approach of the attrition presented by immigrants.

In the Spanish context, consideration could be given to several cities although in this research Madrid has been chosen not only because it is the capital of Spain but, most importantly, due to the fact that it is where the biggest rates of immigration occur. Faced with the impossibility of reaching all the minorities reflected on the report on the population of registered foreign nationals2, Romanians will be our focus as they represent the highest percentage of immigrants living in Madrid (23.78 % of the total foreign population percentage, that is, 205 033 citizens).

The paper is organized as follows: this first section has introduced a brief review of the Spanish migratory situation as well as the objective and structure of this article. Section 2 focuses on the capital of Spain, that is Madrid, as the study will be based on this city. This section will be devoted to develop an exhaustive idea of the Romanian community in Madrid as well as the most relevant years for this immigration. The third part presents the participants of this research the way to recruit. Section four will develop the methodology employed in order to achieve our goals. Section five will discuss the results concerning the main goal of this study and the possible relationship between language use and vocabulary. The last section will conclude the paper by giving some ideas about attrition and the conclusions and guidelines for a possible future research.

Romanian community in Madrid

Before diving in our issue at stake, that is, the Romanian community living in Madrid, a brief note about the foreign population living in this city should be given. According to the report3 published in January 2016, the foreign population stood at 862 085, that is, 13.15 % of the total population in Madrid whereas 86.85 % (5 693 162) represents the Spanish population.

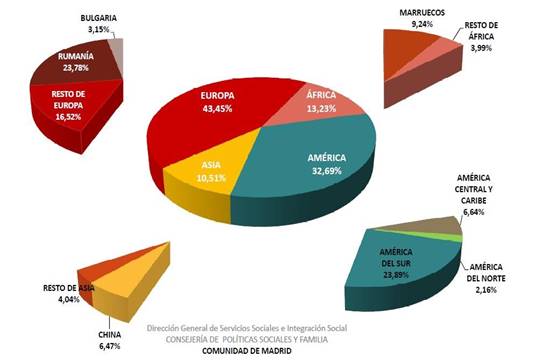

The previous report provides a similar insight that sets forth the foreign population by continents (Figure 1). These data stress the percentage of foreign population divided by continents and by most important countries within each continent.

On the face of it, the highest rates of immigrants come from Europe. The same report also provides an overview of the nationalities with a higher percentage in the Community of Madrid (Figure 2). The three nationalities with the highest percentage of migrants are Romanian (205 033 people), Moroccan (79 639) and Chinese (55 784), that is the reason why the analysis of this study will focus on the Romanian community and will try to yield tangible explanatory findings about this nationality.

According to the World Bank of 2015, Romanian population stands at around 19.83 million and the immigrant share of the Romanian population in Spain has fluctuated over time. Data will be revealed further below.

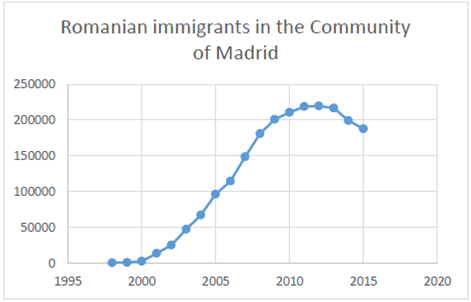

Conforming to Viruela Martínez (2006), in 2002 Romania joined the Schengen area and this fact permitted immigrants came to a greater extent due to the lifting of the Visa requirement. Before the Schengen agreement, Romania had to comply with certain conditions aimed at creating a better legislative framework for the control of Romanian migration but once the Visa was suppressed, immigrants began to migrate. This is confirmed by the number of new arrivals in 2002. In 2001, figures disclosed 13 961 Romanians and with the abolition of internal borders in 2002, Romanians were allowed to enter as visitors in Spain. Hence, a substantial increase of 25 563 Romanians settled in Madrid.

The next important year to be mentioned is 2007 because it is the year when Romania joined the European Union so an intense movement took place (Marcu, 2011). In this year, there were 148 906 Romanians and 2008 brought that figure up to 181 251. In this year, Romanians stood for 31.6 % of European immigrants making them the European nationality with the highest percentage in Spain. They were 14 % of the total foreign population in Spain (Kreienbrink, 2008). This is why some of the Romanian participants in our research had been in Spain less than ten years.

On the whole, from 1998 year in which the number of Romanians was situated in 906, the numbers have gone up to 187 914 Romanians in 2015. In the light of data, the main peak time corresponds to 2007, year in which Romania joined the European Union and year in which 34 350 immigrants arrived to Madrid. Despite this, the crisis facing the country led to a sharp drop in new arrivals from 2013 and the number of immigrants started to drop (Figure 3).

Participants

Having followed a qualitative approach as methodology, twenty-four personal interviews were conducted since June 2015 until March 2016. The participants are middle class first generation migrants who were at least twelve years old when they left their country so their mother tongue was already fully acquired. They have spent from seven to twenty years in Spain, with an average of thirteen years.

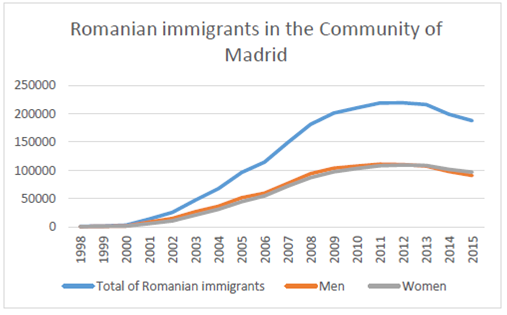

Regarding participants’ gender, no genuine look has been taken on this question, the reason being that the rate for women is higher than for men so no comparable data could be embraced. Following the General Statistics Office (Figure 4), the quantity of men in Romanian migration in Madrid has always been higher to that of women until 2013, year in which women’s quantity starts to be higher than men’s. Despite this widely recognized, the group is composed by nine men (37.5 %) and fifteen women (62.5 %) aged 27 to 45.

Initially, it was sought to recruit participants through networks, clubs, organizations, advertisements but none of these possibilities offered us any participant. A message was directed to the Embassy of Romania to present our thesis and to get the name of associations, radios or newspapers to whom we could address. E-mails were also sent to associations or cultural centers. Unfortunately, the number of answers were inferior to a 5 % (out of more than thirty e-mails, only one answer was received). They offered us help if money was provided. Despite this recognized, access to subjects was gained via personal contacts.

Methodology

The possible relationship between language use and vocabulary is to be clarified and as Schmid (2007) posited in her article “The role of L1 use for attrition”, language use should not be simplified since it is a far more complex issue where several variables interfere. In order to elucidate a possible relationship, the following features should be taken into account.

On the one hand, different variables could affect the fact of using more a language so the first section will analyze all these possible variables before to conclude with the participants’ thought about the quantity of language use that they believe to present in both languages. On the other hand, a specific linguistic task (the Verbal Fluency Task) that has been accomplished by participants will be elucidated with the objective of establishing a possible relationship with the language use and vocabulary.

A semi-structured autobiographical interview was carried out with participants who were provided with clear explanations about the research itself and the tasks that they were asked to accomplish. As participants lived in the same community (Madrid) as the interviewer, locations were suggested by the participants. Therefore, the interviews were conducted in informal settings such as the subjects’ homes, work places, bars, parks, etc. and they were arranged to easily enable participants to attend.

The idea was to elicit a speech as natural and spontaneous as possible within the confines of an interview. A warm-up period of some minutes was used to break the ice and explain deeply the purpose of the interview. This warm-up was followed by the interview itself that finished with the performance of the Verbal Fluency Task. Interviews’ duration depended on the availability of the participant and the desire of sharing knowledge with us. Most of them lasted between an hour and a half and two hours. The interviews were recorded with the participants’ permission except those who refused. That notwithstanding, the same guidelines were followed with them.

Variables that could affect the language use

Taking as a premise the following words: “the native speaker not only needs evidence for developing an L1 system but also needs evidence to maintain his or her L1” (Smith & Buren, 1991, p. 23), situations such as the friends that attriters have, marital status, the neighborhood in which they live, the job that they have and the number of times that they travelled to their origin countries could make attriters maintain their L1 or it could help attrition occur. In order to shed more light on this issue, each one of these situations will be explained.

Regarding their contact with friends, participants indicated that the number of Spanish friends is superior (64 %) to that of Romanian friends (21 %). Therefore, their L1 input includes complete absence or rare input although the main input will come from Spanish friends.

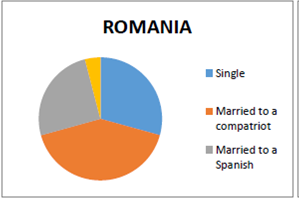

Another situation draws attention to the fact of those participants who have as a partner a person with the same language. If the language used with the partner is different from the mother tongue, it could help attrition to occur. Figures indicate 25 % of Romanians who are in a relationship with Spanish and 41% who are in a relationship with compatriots (Figure 5).

Moving forward the next situation, that is, neighborhoods where migrants usually live, Jaes Falicov (2001) indicated the different losses that migrants must face at when deciding to leave their countries. For her, the recreation of ethnic and social spaces exists in order to restore ties and the fact of living in the same neighborhood will make the new country a more familiar space to live in. In this line, Feraoun (1954) stated that ancestors were in groups by need because, having suffered the isolation, they knew the advantages of living with others.

At the onset of migration, the immigrant will go where his friends or relatives are so he will not feel as a foreigner (Memmi, 2004). To live in the same neighborhood will make him listen to their mother tongue or music, feeling the same cooking smells, in the end, to make the new country a more familiar space to live in. The markets which are found in many countries with specific products from their home countries are a proof of what it has been indicated before. It will be like a psychological return even if they are using the money of the new country and using both languages (Jaes Falicov, 2001).

They choose this settlement as other immigrants from their same nationalities live, thus meaning that the type of contact is always with other migrants who are in the same circumstances than our participants, with the same sociolinguistic environment. Köpke (2007) in her article “Language attrition at the crossroads of brain, mind, and society” posited that those migrants who live in a community in the new country will have an input that will vary a lot as they will be receiving information from other attriters who are in contact with the new society.

In the same line, Clyne (1986) covered this issue by affirming that the input received by an immigrant which is isolated is not the same than the one received by an immigrant who is in a community of immigrants. The first one will only receive input from family so the input will be more uniform but the others will be constantly receiving input from different kinds of people with differences in their language. This is the reason why we cannot refer to migrants and their language use without taking into account the social context in which they live. Erikson affirmed that “individual and society are intricately woven, dynamically related in continual change” (1959, p.114).

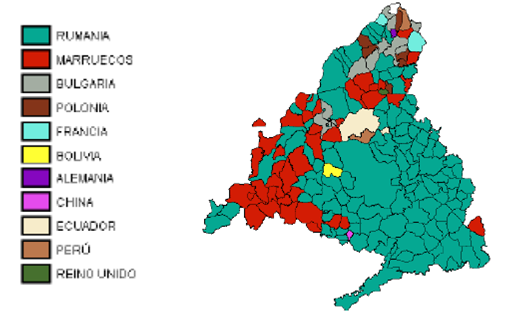

For us, this is a pivotal aspect since the immigrants are thought to live isolated, living in communities and following their customs and language. Madrid will be deeply analyzed in order to see the neighborhoods in which the highest rates of immigration are located. With the goal of being situated, a map of the districts in the Community of Madrid shall be included (Figure 6).

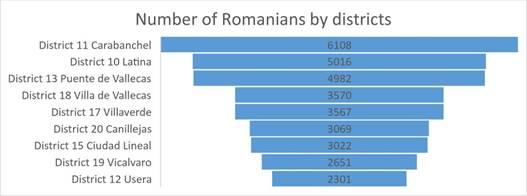

Madrid is divided in twenty-one districts (Figure 6) and the assumption of immigrants living together could be confirmed. Romanians are located mainly in district 11, called Ciudad Lineal, (6 108), in district 10, that is, Tetuán, (5 016) and district 13, Hortaleza (4 982). A more exhaustive outline of the districts with largest concentration of Romanian population will be displayed (Figure 7).

Following Penny (2000), in these situations, a new dialect will be created as the immigrants will go through different processes regarding language. Language use among bilinguals will always entail the bilingual mode to be active, making both languages be active too so the codeswitching usually manifests (Weinreich, 1963; Valdés, 2005). Muhvic-Dimanovski defined this concept as “the alternate use of more than one linguistic system (code) by a bilingual individual within a single conversation” (2005, p. 56). The individual usually takes words or expressions that have not been assimilated from one language as part of speech in the other language.

We concur with the notion proposed by Pavlenko (2004) in which bilinguals make use of L2 words. In this regard, 85 % of Romanians codeswitch when talking in Spanish and following Valdés (2005) or Marcu (2011) it is a normal process.

We will move forward to the following situation which could affect the language use of attriters, that is, jobs. In consonance with Schmid (2007), the use for professional purposes has been shown to be important for maintaining the L1. However, following Yilmaz & Schmid (2012), it does not have a great impact on language performance as the professional use is restricted. The main jobs of Romanian participants are receptionists, doormen, public relationships, construction, cleaning staff, taking care of children, teachers, writers or nurses.

It is our belief that the kind of job is not as crucial as the use of their mother tongues in these jobs. Some jobs are usually carried out by immigrants so they can still use their mother tongues at work although according to participants, when surrounded by Spanish speakers, Spanish will not be used. As they are living in Spain, this is a strong probability.

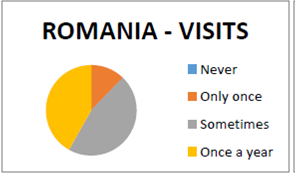

Visits to their origin countries could be recognized as a source of the mother tongue input in light of the increased likelihood of using the language. Given the geographical proximity of Romania, all the participants have at least been once in Romania (12 %). The percentage of those who go every year and those who do not travel every year but have visited the country several times reaches the 40 % (Figure 8).

According to the previous variables, a higher percentage of the use of Spanish language is visible among friends and in the workplace. The quantity of those participants in a relationship with a compatriot is superior than those with a Spanish person but, as mentioned earlier, the codeswitch is so present in the daily life that a full use of the mother tongue is never guaranteed. Albeit participants visit their origin countries in a significant extent, the length spent there would not be appreciable enough to guarantee a complete use of Romanian. From these results, it may be gleaned that Spanish is the main language used among Romanians.

One may hypothesize that language contact or language use is very difficult to measure and research has mainly studied the quantitative aspects of this use or the amount of contact or frequency with the L1 use (Schmid, 2002). In consonance with Schmid (2007) the methodology followed by different researchers has not been the same so we limited ourselves to seek participants’ opinion about their use of languages. They were asked the percentage of their L1 use and their Spanish use that they think to present with the objective of verifying the assertion previously explained, that is, Spanish as the main language used.

The analysis of the results led to the conclusion that Romanians use mainly Spanish on a daily basis (95 % claimed that) so this gives more power to the assertion of the variables displayed. This is in line with the article “Emotions on the move: belonging, sense of place and feelings identities among young Romanian immigrants in Spain” by Marcu (2011) who affirmed that Spanish was the language that participants used more. In 1995, Flege et al. already saw this phenomenon as quite common although they underlined that those who arrived in early childhood would use the new language more than those who arrived later.

Verbal Fluency Task

Schmid & Köpke defined lexicon as “a network of items which are far less densely connected and interdependent than, for example, the phonological inventory” (2009, p. 211) and it is said to be the most vulnerable area in attrition. This is the reason why lexicon has been studied by different authors.

Cook (2002), for example, supported the idea of a L2 speaker with interconnected vocabulary but separate syntax; Köpke (2002) confirmed that bilinguals had problems when retrieving words; Montrul (2004) and Köpke & Schmid (2004) confirmed that the lexicon and semantics are more vulnerable than the syntax or grammar; Schmid & Köpke (2009) also found problems when bilinguals had to retrieve words; Schmid (2011) believed that bilinguals use poor vocabulary and the list goes on and on. With the context laid out above, we are witnessing an area that has been studied much and it is fairly reasonable because the lexicon is the first that springs to the speaker’s mind in the language processing. This is the reason why a Verbal Fluency Task (VFT) was chosen to be accomplished by participants.

The Verbal Fluency Task (VFT) measures the rate of lexical retrieval. In this task, participants are allotted sixty seconds in order to name as many items within a certain category as they can remember (Köpke et al., 2007). This is called semantic verbal fluency as all the words must belong to a specific category (Roberts & Le Dorze, 1997; Yagmur, 1997). We followed the procedure of Waas (1996), Yagmur (1997) and Schmid (2011) so two different stimuli, that is, ‘animals’ and ‘fruit and vegetables’ were needed to be accomplish.

One new feature in this research is that participants were asked to accomplish the task in both languages, Spanish and Romanian as this would allow us to know the language in which they needed less time to retrieve words. All the repetitions were eliminated from the overall count (Spreen & Strauss, 1988) and only a stopwatch and a recorder were needed for this task.

Findings revealed that, on the one hand, the average of fruits and vegetables that Romanians expressed in their mother tongues is 12 whereas the average regarding animals, is 10.8. On the other hand, the average of fruits and vegetables in Spanish is 10.3 whereas concerning animals, the average is 9.2. The average is always superior in participants’ mother tongue, that is, in Romanian.

Regarding the language in which participants accomplished a better performance, the following results were obtained. In the field of fruits and vegetables, 21 % of participants achieved better results in Spanish that in Romanian. Moving into the animal section, 17 % performed better in Spanish than in their mother tongues. These findings suggest that a significant majority continue having a better performance in Romanian than in Spanish. Even those participants with a Spanish partner executed better in their mother tongues, what makes us agree with the study accomplished by Jaspaert & Kroon (1989) in which migrants (Italians in the Netherlands) with a partner from a different language than them (that is, not the Italian) did a better performance in their mother tongue (Italian) than those whose partners were from the same nationality.

Having explained the variables that could affect and the Verbal Fluency Task together with the results obtained, the next section will analyze the possible relationship between language use and vocabulary.

5. Relationship between language use and vocabulary and between language use and attrition

The results substantiate the argument that Spanish would be the most spoken language among Romanians and this assertion is underpinned by 95 % of participants who claimed to present a higher use of the Spanish language in a daily basis.

Regarding the Verbal Fluency Task, findings illustrate that the quantity of terms mentioned in Romanian is superior than the quantity in Spanish. The percentage of participants who performed better in Spanish is substantially inferior to the same in Romanian.

When putting all findings from this study together, it does not ensure to establish a connection between language use and vocabulary. Romanians need more time to retrieve words in Spanish whereas the terms in their mother tongue come to their mind easily and quickly. Would be too narrow as approach the possible relationship between language use and vocabulary, therefore the possible relationship between attrition and language use will be also examined.

The possible relationship between both parameters has always been an ambivalent topic due to the different approaches. Paradis (2004, 2007) stated that language use is considered to be the most important factor for language attrition. However, some researchers expect that attrition will be more perceived in those who use their L1 less frequently whereas other studies show a negative correlation.

Among those who concur with the relationship, Köpke (2007) thinks that language use has always been in a relationship with activation and inhibition. Andersen (1982), Green (1986), de Bot et al. (1991), Paradis (1985, 1993, 2004, 2007), Ammerlaan (1996), Hulsen (2000) and Köpke (1999, 2007) also pointed out that those items which are not used a lot, they are more vulnerable to attrition. Paradis (2004, 2007) suggested as well that the lack of use of the mother tongue together with a frequent use of the L2 will reduce accessibility of lexical knowledge.

On the contrary, some studies show a negative correlation between language use and attrition. For example, Gürel (2002) believed that a limited use or a non-use of the L1 will would not always lead to a strong attrition. Schmid (2007) certifies that the level of attrition and the frequency of the first language use do not have any relationship and if it does exist, it is a very small correlation.

As from this baseline and bearing in mind that language use and vocabulary do not seem to trigger a relationship, we esteem that language contact or use is not a decisive factor in attrition either; consequently, language use will not be necessary in order to maintain the mother tongue.

As reported by Köpke (2004), we believe in the importance of not only one variable but many of them in the attrition process so it is our belief that this relationship should not be either simplified due to the numerous factors that might appear in attrition and that could be the reason for maintaining or losing a language. Of greatest interest perhaps is the belief that all these variables happening at the same time are the cause for attrition. Some of these possible features will be discussed to conclude with those which may help attrition to occur.

Starting with those factors which have been found to correlate with the maintenance of the mother tongue, we should mention emigration motivations such as ideological or political and new aspirations. Ben Rafael & Schmid (2007) confirmed this assumption in their research about immigrants in Israel in which Francophone immigrants maintained their language much more than Russian immigrants who were in Israel on account of economic reasons. Participants in our research seem to be within an economic migration type together with a better welfare.

The analyses by Christian (1977) also yielded tangible explanatory findings in this maintenance or attrition of mother tongue. For him, the fact of being able to read in the mother tongue creates on the speakers a feeling of prestige which makes them to be more motivated to maintain their L1. All the participants in this research expressed their ability to read in their mother tongues. It must be born in mind that migrants were older than twelve when moved to Spain which means that all of them had completely acquired their mother tongue before the onset of attrition.

Romanian is the language at stake and considering that Romanian language stems from Latin as does Spanish, it is therefore reasonable to find similarities in both languages. Romanians should not encounter as many problems as other migrants with languages completely different to Spanish.

According to Penfield & Roberts (1959), the brain plasticity in adults will not allow them to adapt very quickly to new situations as this plasticity has changed because of the age; hence, participants will have more problems when adapting to new languages.

Respecting the loss of the mother tongue, Gardner & Lambert (1972) and Pavlenko (2002) saw the attitude, motivation and other emotive factors towards the second language as crucial for the attrition to occur. More specifically, Ben-Rafael & Schmid (2007) and Schmid (2002) estimated that a positive attitude will enable the L1 maintenance and a negative attitude will lead a quicker attrition. Nearly all participants expressed their desire and good predisposition toward the new language and seemed being well disposed to become part of the new society.

In the same line and though not present at this research, other emotional features could be of utmost importance. Schmid (2002) stated that exception settings such as persecution might confirm that emotional factors are the most significant extralinguistic factors in attrition. Others settings as international adoption could be as well a variable for L1 attrition.

In the same way as the possible relationship between language use and vocabulary has its supporters and critics, the possible relationship between language use and attrition presents the same scenario. In 2007, Paradis observed that a positive emotional attitude will enable a better acquisition of the second language, hence there will be an impact on attrition. Nevertheless, Schmid (2007) and years later, Yilmaz & Schmid (2012) did not see any relationship between these parameters. As highlighted previously, our belief reaffirms that language use and attrition are not directly interwoven.

On the whole, some variables could make Romanians to maintain their mother tongue. Participants are able to read in their mother tongues; their brain plasticity will not enable them to adapt quickly to the new language and Romanian language stems from the same language as Spanish does. However, features such as the willingness to have a better life and their attitude could help attrition to occur.

As reported by Yilmaz & Schmid (2012), these factors are extremely difficult to measure because they are not objective and notwithstanding that measuring the amount of attrition is an impossible task (Köpke, 2004), participants were inquired about two different aspects. On the one hand, they were asked about the importance accorded by them to the maintenance of their mother tongue. On the other, it was extremely important to know their opinion about the possibility of losing completely the mother tongue and the percentage of their mother tongue that they thought to have lost.

In relation to the maintenance of their mother tongue and although Waas (1996) asserted that attitude influenced self-perception but not proficiency, it is relevant to note that for most of them (70 % of participants) believe that it is definitely valuable to maintain it. Therefore, first generation is sensitive regarding the fact of preserving the mother tongue as a medium of communication. The same applies to the research made by Yilmaz & Schmid (2012) in which mother tongue was considered to be the language used at home with children.

Concerning the loss of language, 22 % of participants estimated not having lost anything whereas 40 % of them think to have lost among 1 % and 20 %. Only one person claims to have lost more than 50 %.

Based on this finding, Romanians seem to stress the importance to their mother tongue and the way to stress it is by maintaining it. Their perception towards having loss their mother tongue is not high. This together with the fact of using more Spanish in a daily basis leads us not to establish a straightforward relationship between both variables, that is, language use and attrition. Even though, this research provides some suggestions for future research that could intend to result in more accurate results.

Conclusion

Findings from the Verbal Fluency Task have revealed that the performance among Romanians is still better in Romanian than in Spanish. Despite the fact that Spanish is the language most used in a daily basis, Romanians seem to need more time to retrieve words in Spanish whereas the terms in their mother tongue come to their mind easily and quickly.

Having this is mind and when putting all findings from this study together, they lead us to infer that a relationship between vocabulary and the language use is not perceived and if it exists, it is not a deep relationship.

In line with Yilmaz & Schmid (2012), no relationship was found among language use and attrition, hence, this relationship should be considered as unsuitable as a reference point. The investigations demonstrate that the big majority of participants think to have lost something of their mother tongue but not in a big quantity. Even though, it is important to mention that, according to Weltens (1988), self-evaluation would not be a valid measure in order to establish if a participant is suffering attrition or not. For him, attriters tend to enlarge their linguistic loss and results do not show the same than they expressed.

With this complexity in mind, a possible relationship between language use and vocabulary and language use and attrition is not clearly identified.