Italian emigration and law in the USA

One of the most important waves of migration in historytook place in Europe at the end of the 1800s and continued wellinto the 20th century. According to Turchetta (2005, p. 4)[1] in Italyalone between 1876 and 1976, 25.8000.000 people had left tosearch for a better life in almost every corner of the planet. Half ofthese people migrated before World War I, thus before any legalrestriction was implemented, such as the Literacy Act[2] enacted bythe United States of America in 1917, which read as follows:

“To exclude aliens over sixteen years of age, physically capableof reading that cannot read the English language orsome other language or dialect, including Hebrew or Yiddish.”

Later another restrictive law was imposed known as the QuotaAct which proposed a quota on the number of new immigrantsequal to the percentage of migrants already living in the country.With these two laws, of course, the number of Italian migrants inthe US decreased onsiderably and in fact increased towards otherareas of the world. Turchetta (2005, p. 4) goes on to explainthat out of 25,000,000 Italians who left Italy, only 7,000,000 maybe considered expatriates because the rest, around 20,000,000, returnedto Italy after some time abroad.

Typology of migrants

According to Bettoni (1993, p. 412)[3] the Italian migrants may beclassified as follows:

Neither the first migrants’ grandchildren nor great-grandchidren.

Not the very last migrants who had departed from Italy in the 50s and 60s.

The first classification has to do with a socio-linguistic factor,whereas the second has to do with a demographic variable. Accordingto Bettoni, language loss is common in third and fourth- generationItalians around the world. Moreover, migration in the 50sand 60s constitutes a more consistent and very different kind fromthe previous groups before the two world wars given the politicaland historical environment during those years in Italy and Europe.It is important to note that the colony of San Vito in Costa Ricawas founded by Italian migrants during these years.

3. Arrival in either highly rural or industrialized regions or countries.

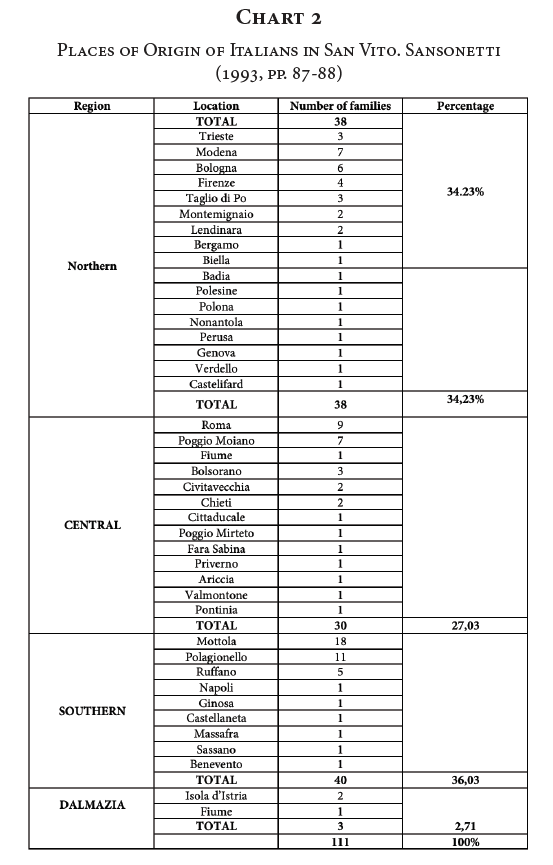

Italian migrants incorporated into societies such as Canadaor USA present different characteristics of assimilation at the linguisticand social level than those incorporated into areas in theprocess of development or with a basic economy, such as Mexicoor Costa Rica. These last Italian migrants into Mexico came aloneand showed more unity; they were mostly from Veneto and thusgave birth to “Chipilo,” a variant of Venetian Dialect spoken todayin the state of Puebla, Mexico. On the other hand, the migrantswho colonized the Valley of San Vito had many different places oforigin on the Italian peninsula and consequently their linguisticrepertoire show important differences as studied later.

4. Those who returned, and those who remained.

5. Arrival in a European or a non-European country.

6. Cultural and economic prestige of Italy in the new country.

7. Language of the new country.

The language of migrants

With regards to the language of migrants and its impact inthe peninsula and abroad Vedovelli states that:

…“150 years have produced profound changes in the linguisticidentity of the Italians. Daily use of the commonlyspoken Italian and immigrant languages input are the mostobvious signs of identity tensions experienced by our society.Linguistic tensions have been carried out by millionsof Italians who, at various times, have left the country to“make a fortune” in America or in Australia, Asia and Africaonce usually dialectophone, illiterate and poor, now, as“brains on the run”, graduates and italophones.What linguistic changes have affected our emigrant communities?What relationships have had with the Italian language?How has it clashed with the languages of the host country?What has been the fate of the Dialects, once away fromtheir territories? What have Italian governments done withthe linguistic identity of Italian communities around theworld? And what to do with today’s “global market of languages?”(Cover, 2005)

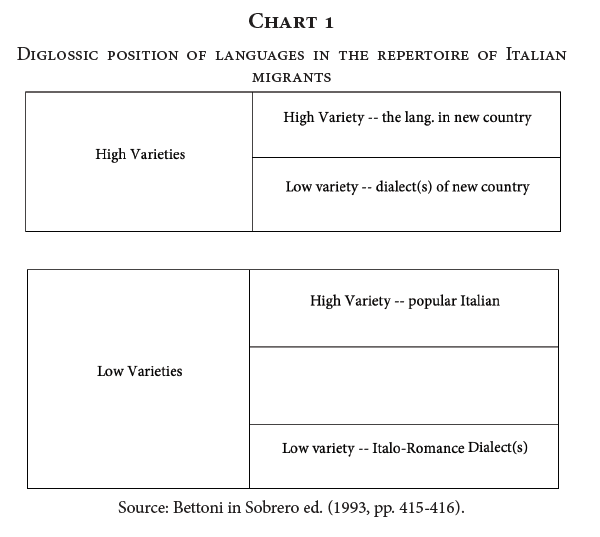

In general terms, and as mentioned by Vedovelli above,migrants are supposed to speak Italo-Romance Dialects as theirfirst language. Moreover, as proposed by Bettoni (1993, p. 415) theItalophony of migrants is considered to be definitively non-standard.In fact, the higher variety constitutes popular Italian variety. According to Turchetta (2005, p. 5) given the historical and politicalissues inside the peninsula in post Unitarian times, two importantcharacteristics of migrants were illiteracy and higher competencetheir regional Dialect. On the other hand, competence in theUnitarian dialect was very low or non-existent during this period.Moreover, we need to take into consideration that majority of thispopulation came from economically depressed areas, as opposedto people already living in more industrialized cities. The process of education then began in the new country, first because it wasnecessary to communicate in a single language with other Italiansfrom different regions, and second because it 10 was necessary tolearn to write in order to keep in contact with families left behind.It is important to say that the new country opens the door for thenew generations to study in order to integrate them into the newculture, society and economy, as well as opening door to acquiringa foreign language. This process of education affected not onlythose who had migrated and remained in the new land, but alsothose who had returned to Italy, because they represented a modelof progress for the non-migrant population especially beforeWorld War II. All these factors of illiteracy and poverty togetherwith the Dialectophone nature of migrants have produced highlypidginized and mixed forms of Italian spoken abroad when confrontedwith the new language and local dialects. On the otherhand, processes of language loss or attrition are evident in the firstgeneration, and consolidated in the second and third generations,mainly because of the very low sociolinguistic value they gave tothe language or languages of origin. How does a language of origin coexist with new language(s) in a different land? How doesthis language of origin combined with local languages contributeto the rise of local varieties? A framework aiming to answer thesequestions will be presented in the following section.

Diglossic position of languages

For Bettoni in Sobrero ed. (1993, pp. 415-416) the diglossic positionof languages in the verbal repertoire of Italians abroad maybe observed in the following chart:

The Italians in Costa Rica

Source: Taken from: http://www.cotobrus.net/el-canton/209-san-vito-de-cotobrus.html[4]

Map 1 Geographic location of San Vito de Coto Brus in Costa Rica

According to Bulgarelli (1989, pp. 4-7)[5] the Genovese presencein Costa Rica can be traced back to 1502, when ChristopherColombus landed on the Caribbean coast of Costa Rica. The firstdocumented arrival of Italian citizens, however, took place onDecember 12, 1887, when seven hundred and sixty-two workers,mostly from Mantova, arrived in Puerto Limon in the Caribbeanzone to work on the construction of the railroad which wouldconnect the capital, San Jose, to the Caribbean port of Limon. Sixmonths later, six hundred and seventy-one Italian men arrivedin the same port. Bulgarelli states that many of them returned toItaly; half of them, however, remained. A second wave of Italianimmigrants in Costa Rica took place after World War I. Accordingto Bariatti (1989, p. 5)[6] one hundred and sixty-two Italians lived inthe capital city by 1927. The sample shows that with regards to theuse of Italian language, only 35% of this second wave spoke standardItalian, mainly because they learned “in loco.” Offspring weresent to study to Italy, which constituted a great honor and pride fortheir parents. Another reason that they speak standard Italian isthat the members of the second generation married other Italians.The rest -- 65% -- of this second generation did not speak standardItalian at all. Among the grandchildren, only 15% of them had studiedin Italy and had learned the language at home.

In Sansonetti (1995)[7] the settlement and foundation of SanVito de Coto Brus is described in detail. This constitutes the thirddocumented arrival of Italians in Costa Rican territory.

Out of 111 families who came to colonize San Vito de CotoBrus, 38 came from different towns in the north of Italy, 30 fromcentral Italy, 40 from southern Italy, and 3 from Dalmatia. Theywere mostly farmers and peasants. Sansonetti, on the other hand,was a soldier and a political science graduate. Married to OliviaTinoco, a Costa Rican woman whom Sansonetti had met in Romeyears before, Vito Sansonetti along with members of his family andother Italians founded SICA, an organization created to promotethis colonization. “San Vito,” the Italian name of the town, is afterthe patron saint of migrants. The rest of the town’s name, “CotoBrus,” dates back to what indigenous people called the place previousto the arrival of Europeans. The origins of these last migrantswill be examined in the following chart.

Given the fact that these families came from different locationsand with different Italo- Romance Dialects, but also taking intoconsideration that it is possible that many of them had some instructionin the National Italian language, the tendency towardsusing Standard Italian more and more among themselves to understand each other at work, in the street, at church and so forthwas probably the rule, as presented in the next section.

The languages of Italian immigrants in San Vito

According to Franceschi (1970, p. 89)[8] the Italians who arrivedin San Vito spoke Italo- Romance Dialect, but also regional Italian.He refers to the interviews as revealing great influence from the regionalItalian, Italo-Romance Dialect, and sometimes from Spanish.At the end of his research, however, he concludes that StandardItalian constituted the most commonly used variety among membersof the first generation, and that the second generation spokeSpanish as their main language. The following example was takenfrom an interview with a young Italian man who shows influenceof middle Italian with clear interference from Sapnish as seen infinca It. Standard: fattoria

“Ho comprato pure una finca, stavamo preparando purele carte, mi son fatto pure io, pure mio fratello, e pure lapaterna.” (Franceschi, 1970, p. 95)

Another example corresponds to a woman with great influencefrom Veneto, Laziale regionale, and Italo-Romance Dialect:

“Cene (-cen’è) ancora, ci stave il dolce, non ci stasanti, non ce stava maniera, un comisariato che ci stave unpo’ di tutto, s’era qua.” In quest’italiano laziale s’intersecaquello véneto: lèto, late, deto, il meljo, e il dialettooriginario: grande (femminile plurale), vedest, let, fat,pers tut. All’abitudine allo spagnolo sarà da riportare lasibilante sorda in case, piaser, mentre piuttosto dall’ italianocentromeridionale verrà il sintagma la spesa nostra. Ladonna passa continuamente dall’ italiano al dialetto,”(Franceschi, 1970, p. 97).

The influence of Spanish

The influence of Spanish on the varieties of Italian may be seenin the following typology (Franceschi, 1970, pp. 226-228).

1. Spanish words in the lexicon with no variation from Italian or borrowings

Examples: Geographical names, names of people, exclamations, adverbial expressions.

2. Spanish words integrated into the Italian system

Examples: traspianta – Spanish – transplanta; due finche – Spanish – dos fincas; due peoni – Spanish – dos peones; I peones or I peoni – Spanish – los peones.

3. Loanwords from Spanish

Pigna – Spanish – piña – Italian– annasso

4. Pragmatic calques

Chiaro! – Spanish – Claro!

5. Syntactic calques

La ho vista facendo; ho continuato seminando

6. Hybrid forms

l’aggua, émo avutto, aviamo écio

7. Use of local expressions in discourse

…y así terminó el problema...

8. Phonology

Reduction of intervocalic stops to fricatives - especially/b/ - aswell as reducing the voiced sibilant to voiceless in the same position,pronouncing /r/ with a marked local accent usually at thebeginning (closer to a rhotic fricative alveolar, the typical CostaRican /r/)

Conclusions found in Franceschi

At the end of the research, Franceschi concludes that in spiteof the multiple Italo- Romance Dialects spoken, and the influencefrom Spanish, Standard Italian is the most widely used variety becauseof the high value given to it, and also because it made communicationsimpler, faster, and evidently more efficient amongpeople with diverse origins and Italo-Romance Dialects. However,in the second generation, an evident stage of erosion is visiblebecause of the influence of Spanish. That is, they prefer to speakSpanish as L1. The use of regional Italian Dialects is restricted tofamily and friends, especially those from the same region or townin Italy. He also concludes that the choice for any of the previouslymentioned languages in the repertoire is conditioned by severalfactors such as education, age, sex, origin in Italy, relationship withthe national Spanish or Costa Rican culture, marital ties with CostaRicans, and so forth. With regards to this topic he states that:

“Nella comunità sanvitegna l’italiano ha tronfato sui dialetti,quale strumento di comunicazione più funzionale, oltreche dotato di maggior prestigio. Nella seconda generazionela lingua a sua volta va regredendo da fronte allo spagnoloche per i giovani non solo è più funzionale, rispetto all’ambientecostarricense in cui ormai si trovano a vivere ma èassai meglio posseduto dell’Italiano (generalmente scarso,o semidialettale, già nei padri) rispetto a cui gode,graziealla scuola,anche del prestigio della lingua di cultura.Gli elementi che hanno causato il vario comportamento linguistico dei coloni sono indubbiamente numerosi; maad alcuni si può attribuire una validitá di ordine generale.Il primo da prendere la considerazione è il posseso dellinguaggio originario: che di norma è un dialetto. Un suopieno posseso appare infatti indispensabile per una buonaconversazione, in rapporto sia in all’italiano sia allo spagnolo.Il ben maggiore possesso che il parlante ha del vernacolorispetto alla lingua spiega il minimo (talora nullo)cedimento del primo all’ influsso del castigliano.” (Franceschi, 1970, pp. 359-361)