Introduction

Galway Kinnell is a major contemporary poet who may be unknown to many and whose masterpiece, The book of nightmares, parades humanity’s endless life cycles. This poet’s literary piece unveils a journey of self-discovery for which the acceptance and experience of death through a life cycle, in which living involves death and death living is not only necessary but essential. Most human beings have been taught to have living as the center of their interests and fear death. Though, for Kinnell the latter starts at the moment of birth; it is a paradox that when an individual starts living in the world s/he also launches its death. In other words, “living life” is accepting death as our companion; besides, according to Kinnell’s vision of the world, both are part of a necessary cycle to become one with nature. Furthermore, that this cycle is life’s relentless continuum. Octavio Paz (1995) confirms this revelation when he states that

¿Quizás nacer sea morir y morir nacer? Nada sabemos, todo nuestro ser aspira a escapar de esos contrarios que nos desgarran, pues si todo (conciencia de sí mismo, tiempo, razón, costumbres, hábitos) tiende a ser de nosotros los expulsados de la vida, todo también nos empuja a volver, a descender al seno creador de donde fuimos arrancados. Y le pedimos al amor - que, siendo deseo es hambre de comunión, hambre de caer y morir tanto como de renacer - que nos dé un pedazo de vida verdadera, de muerte verdadera. No le pedimos la felicidad, ni el reposo, sino un instante, sólo un instante, de vida plena, en la que se fundan los contrarios y vida y muerte, tiempo y eternidad pacten. Oscuramente sabemos que vida y muerte no son sino dos movimientos, antagónicos pero complementarios, de una misma realidad. Creación y destrucción se funden en el acto amoroso; y durante una fracción de segundo el hombre entrevé un estado más perfecto (p. 343). 1

Like Paz, through his poetry, it can be asserted that Kinnell believes that humanity denies itself the deepest experience of real life: there must be a reconciliation of binary oppositions2 in this unremitting experience that individuals have defined as life.

Rites and myth, within their symbolic nature, have permeated human life for ages; however, reasoning has displaced their significance. It has become easier to belittle significant moments of life so that life may seem less complex to live; nevertheless, it becomes more unintelligible for time cannot be stopped and aging is the inherited path of humanity. Consequently, people cannot avoid experiencing rites but acknowledging them; Kinnell, on the contrary, discusses these rituals and the wisdom they may bring to the reader in his book-length poem. This poetic text presents an awakening of the need of going back to a more ritualistic life experience in which symbols may guide the individual to achieve plenitude in life and in death for “si nuestra muerte carece de sentido, tampoco lo tuvo nuestra vida3” (Paz 1995, p. 189), both moments in life are vital in the cycles of the world. Moreover, concerning myth, Campbell (1991) states that

Mythologies teaches you what’s behind literature and the arts, it teaches you about your own life… Mythology has a great deal to do with the stages of life, the initiation ceremonies as you move from childhood to adult responsibilities … all those rituals are mythological rites. They have to do with your recognition of the new role that you’re in, the process of throwing off the old one and coming out in the new (p. 14).

Taking into consideration Campbell’s statement, human beings experience myth and ritual every day of their lives; and it is through the “personal or communal mythology” that they undergo, that people ascribe meaning to their existence. Life becomes more than an act of being alive but of making sense of what is lived. Regarding the function of ritual, Campbell (1972) affirms that:

As I understand it, is to give form to human life, not in the way a mere surface arrangement, but in depth. In ancient times, most social occasions were ritually structured, and the sense of depth was rendered through the maintenance of a religious tone. Today, on the other hand, the religious tone is reserved for exceptional, very special, “sacred” occasions. And yet even in the patterns of our secular life, ritual survives. It can be recognized, for example, not only in the decorum of courts and regulations of military life, but also in the manners of people sitting down to table together (p. 44).

As Barthes (1999) also emphasizes, myth abolishes the complexity of human acts, it gives them the simplicity of essences, and it disregards all dialectics, with any going back beyond what is immediately visible and it organizes a world which is without contradictions. Things appear to mean something by themselves (p. 124). Thus, as this research focuses on the how ritual is still part of humankind, this study will concentrate on how the hero of the poem moves forward in his journey for learning to finally acquire knowledge that will best serve him in life. As Campbell (2004) affirms, “the hero has died as a modern man; but as eternal man - perfected, unspecific, universal man - he has been reborn” (p. 15).

Methodology

This research focuses on the analysis of Kinnell’s poetic work The book of nightmares taking as a basis Campbell’s archetype of the monomyth, the hero’s journey. Considering the reading of The book of nightmares through an archetypical approach, myth is essential. Thus, from the many differing theoretical approaches to myth and archetypes, those of Carl Gustav Jung and Joseph Campbell are favorable for this study since these scholars work with the mythical and archetypal position. Furthermore, contributions from the Mexican scholar Octavio Paz and his position on the binary opposition4 life and death will be included. Consequently, these theoretical frames will offer the approach for reading the book-length poem aiming to converge on the relation between the content and context of the text with the theories chosen for the analysis. Accordingly, the theories of Jung and Campbell will be interrelated in that they develop a critical basis for discussing the concept of myth and the archetype of the hero’s journey.

Jung (2006), in The undiscovered self, indicates that an archetype “when represented to the mind, appears as an image which expresses the nature of the instinctive impulse visually and concretely, like a picture” (p. 81). It is through the reading of The book of nightmares from a mythical and archetypal stance that the function of the hero’s journey will be analyzed, alerting readers to specific and precise constructions of the journey to attain the resolution of binary oppositions (life-death) when “one/ and zero/ walk off together” (Kinnell 1971, p. 73). In Kinnell’s The book of nightmares, the three main phases of the monomyth will be analyzed as follows:

Separation or departure: a classic situation in which the hero faces his call and needs to enter the dark forest, find the great tree and the chatting brook besides underestimating the façade of the carrier of the power of fate. These elements can be found in poems I, II, and III.

Trials and victories of initiation: this second traditional phase in the monomyth represents the movement forward into a hazardous journey that may be physical or psychological, premeditated, or accidental. And so, it happens in The book of nightmares. Poems IV to VIII lead the persona into an unknown world where he listens and sees symbolic elements of life and death and when he feels trapped in the face of life as a fly may feel trapped in a spider’s web, feeling alone for he “has no one to turn to because God is my enemy. He gave me lust and joy and cut off my hands” (Kinnell 1971, p. 30).

Return and reintegration with society: after undertaking different ordeals and learning his lesson, the hero needs to bring back to society the knowledge acquired throughout the journey. In poems IX and X, the hero returns, positioning himself “On the path winding/ upward, toward the high valley” (Kinnell 1971, p. 65).

The archetype of the hero’s journey

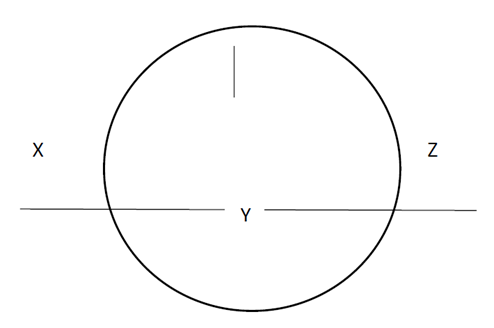

When a person agrees on deciding, s/he is usually positioned at an active role, to choose from more than one option, and when picking there will be a trail to follow and consequences are hard to avoid. The routes that a person may opt for in life can reflect specific situations and emotions that guide them into the selection made. Many times, these same situations have been undergone by others and it is these previous experiences the ones that could enrich life as the persona who will commence his journey in “Under the Maud moon” on the path where he lights “a small fire in the rain.” According to Campbell (2004) “The standard path of the mythological adventure of the hero is a magnification of the formula represented in the rites of passage: separation - initiation - return: which might be named the nuclear unit of the monomyth” (p. 23):

Figure 1 Description of the standard path of the adventure of the hero according to Campbell (2004).

The Monomyth or the archetype of the hero’s journey

While there have been different approaches to reading Kinnell’s book-length poem, their primary concern is Kinnell’s work in relation to other poets of his generation rather than the analysis of the book-length poem as a unity in which archetypes and myth intersect. Hence, there are very few works that analyze the poem from an archetypal stance and the aim is to contribute to scholarship with this research. Therefore, for the purpose of this study, the Jungian archetypal approach will be assumed as well as Campbell’s pattern of journey of the hero.

A. Separation or departure

The moment of separation for the hero, in Campbell’s motif, represents the moment of releasing the unknown within himself and, as the scholar affirms “A blunder - apparently the merest chance - reveals an unsuspected world, and the individual is drawn into a relationship with forces that are not rightly understood” (Campbell 2004, p. 42) but that awakens a strong fascination in the hero. In the first poem of The book of nightmares, “Under the Maud moon,” the persona faces the path where people have failed to get warm and be saved as they have “unhousel[ed] themselves on cursed bread, / failing to get warm at a twigfire.” It is then when, unexpectedly, the persona realizes that “the deathwatches inside /begin running out of time;” he must start his journey for

The raindrops trying

to put the fire out

fall into it and are

changed: the oath broken,

the oath sworn between earth and water, flesh and spirit, broken,

to be sworn again,

over and over, in the clouds, and to be broken again

over and over, on earth (p. 4).

It is in this moment when the persona receives the call of the tramp to start the journey seeking to give “you a line to connect with that mystery which you are; and all of these wonderful poetic images of mythology are referring to something in you” (Campbell 1991, p. 91). The speaker is waiting to commence his walk on the path with the challenge of a chaotic moment that can only offer a feeble promise of harmony. The imagery of rain falling on fire reveals a common binary opposition; in this case, rain and fire become one. Moreover, it is in this instant when the hero sits

a moment

by the fire, in the rain, speak

a few words into its warmth -

stone saint smooth stone - and sing

one of the songs I used to croak

for my daughter, in her nightmares (p. 4).

It is this “moment, of spiritual passage, which, when complete, amounts to a dying and a birth. The familiar life horizon has been outgrown; the old concepts, ideals, and emotional patterns no longer fit; the time for the passing of a threshold is at hand” (Campbell 2004, p. 43). This is the beginning of the symbolic death, that moment when individuals realize that a cycle is over and it needs to restart. Nevertheless, it is mandatory to “croak” and to “howl” when “the one / held note / remains - a love note / twisting under my tongue, like a coyote’s bark / curving off, into a / howl” (p. 4), a cry of desperation that cannot be understood. It is this moment of departure the one that unlocks the mystery of life with the prenatal existence of each human being and the subsequent birth of a baby:

It is all over,

little one, the flipping

and overleaping, the watery

somersaulting alone in the oneness

under the hill, under

the old, lonely bellybutton

pushing forth again

in remembrance,

the drifting there furled in the dark,

pressing a knee or elbow

along a slippery wall, sculpting

the world with each thrash - the stream

of omphalos blood humming all about you (p. 5).

Prenatal life is a struggle just as life is, the fetus is alone and “under / the old, lonely bellybutton” until the moment of birth when “the grip of departure, the slow / agonized clenches making / the last molds of her life in the dark,” until “she dies / a moment, turns blue as coal” (p. 6); or as Paz (1995) asserts that “vida y muerte son inseparables5” (p. 194). However, the persona in the poem is not aware of this fact and he is suffering and afraid that even nature is involved in a never-ending cycle that embraces death and it is then when he is summoned:

Listen, Kinnell,

dumped alive

and dying into the old sway bed,

layer of crushed feathers all that there is

between you

and the long shaft of darkness shaped as you,

let go.

Even this haunted room

all its materials photographed with tragedy,

even the tiny crucifix drifting face down at the center of the earth,

even these feathers freed from their wings forever

are afraid (pp. 14-15).

The persona feels lost and terrified when facing the reality of dying for without knowing he has been discarded; therefore, “the subject loses the power of significant affirmative action and becomes a victim to be saved” (Campbell 2004, p. 49). However, it is then in “The shoes of wandering” that the persona encounters the tramp’s shoes and he discovers “the eldershoes of [his] feet / as their first feet, clinging down to the least knuckle and corn” and he “walk[s] out in dead shoes, in the new light” to understand that “the first step, the Crone / who scried the crystal said, shall be / to lose the way” (p. 19). In this sense the hero meets an individual who “provides the adventurer with amulets against the dragon forces he is about to pass” (Campbell 2004, p. 57). Hence, the charm given to the persona is humanity’s knowledge and the shoes for “the old / footsmells in the shoes, touched / back to life by my footsweats, as by / a child’s kisses, rise” to start the crossing of the first threshold as the path opens completely and a road witnessed by trees that burn “a last time” (p. 21), an allusion to the Bible’s burning trees as bearers of a truth, open his way to “the road,” his path to knowledge, but “the road / trembles as it starts across swampland streaked with shined water” (p. 21). However, this “water” will be accompanied by “a lethe- / wind of chill air” (p. 21) that will stroke him “all over [his] body” (p. 21), trying to make him cast his memories to oblivion as he crosses his own Hades6. In this abstraction, the persona’s symbolic journey to death

certain brain cells crackle like softwood in a great fire

or die,

each step a shock,

a shattering underfoot mirrors sick of the itch

of our face-bones under their skins,

as memory reaches out

and lays bloody hands on the future (p. 21).

As the hero enters this path, his rational being loses as much strength as he gains experience, it becomes a give-take promenade that leads him into anxiety and fear as the relentless memories on which he strolls makes him see that beyond flesh there is nothing but bones. The trail quivers and as he walks, he is confronted with a reflection in which the face echoes life and the bones death, an unresolved binary that troubles him. Subsequently, these recollections taint his walk as “the haunted / shoes rising and falling / through the dust, wings of dust / lifting around them, as they flap / down the brainwaves of the temporal road” (p. 21). He realizes that the shoes, the symbolic element that represents him, his walking and humankind, as they are haunted, cannot fly and take him away of pain and grief. The shoes are “haunted” because in each shoe there is a little of every individual on earth, and all human beings will one day wander “the temporal road” (p. 21) of the life-death continuum. As Campbell (2004) asserts “The idea that the passage of the magical threshold is a transit into a sphere of rebirth is symbolized in the worldwide womb image of the belly of the whale. The hero, instead of conquering or conciliating the power of the threshold, is swallowed into the unknown, and would appear to have died” (p. 74). Indeed, it is in this moment when the persona feels that there is no escape from death and pain; moreover, he may ponder about his demise.

Consequently, the persona will start his journey, deliberately, into the darkness, to start learning about who he is and who he may become. After taking off the shoes and started descending into his path, in his dream, the path opens as the route becomes darker. He is now in the belly of the whale7 as he wanders

On this road

on which I do not know how to ask for bread,

on which I do not know how to ask for water,

this path

inventing itself

through jungles of burnt flesh, ground of ground

bones, crossing itself

at the odor of blood, and stumbling on (p. 22).

As Campbell (2004) affirms, for those who start the quest and find themselves in the belly of the whale “emphasis is to the lesson that that passage of the threshold is a form of self-annihilation. The disappearance corresponds to the passing of a worshiper into the temple - where he is to be quickened by the recollection of who and what he is, namely dust and ashes unless immortal” (p. 77). So does the quester feels this agony of walking on this graveyard that seems to take him nowhere as it “cross[es] itself,” humankind’s path is never straight as it opposes “itself / at the odor of blood” (p. 22). However, it is in this moment when he, as in a shrine, “long[s] for the mantle / of the great wanderers, who lighted / their steps by the lamp of pure hunger and pure thirst,” (p. 22), knowing that “whichever way they lurched was the way” (p. 22), for the metaphor of the way is open to the different people that walk the path. For example, for each person, there may be a different path to walk because humanity seems to long for redemption and which is only accomplished individually. It would be unrealistic to believe that the trail the hero walks will be the same for other people; indeed, everyone must walk his/her path in order to acquire that knowledge that s/he lacks.

The persona seems to be desolate and adrift looking for the cloak of those who have traveled this path before; the hero wants to feel protected with this symbolic mantle, a cloak that has been worn by those that already walked and lighted the path and like them know that “whichever way they lurched was the way” (p. 22). However, he feels lost and his feeling of despair is enhanced when “(…) the Crone / held up [his] crystal skull to the moon” (p. 22). It is then when the quester encounters “the Goddess,” the Crone; hence, as Campbell (2004) affirms “the ‘bad’ mother too persists in the hidden land of the adult’s infant recollection and is sometimes even the greater form” (p. 92). This woman grabbed his “crystal skull” and as she hold it to the moon, the hero was positioned “across the Aquarian stars,” symbolic element that denotes the union of two opposing forces or of two halves, as he is part of two realms, the spiritual and the mortal, as well as belonging to the contrasting realms: life and death. The Crone then declares

poor fool,

poor forked branch

of Applewood, you will feel all your bones

break

over the holy waters you will never drink (p. 23).

She refers to the Christian symbol of the apple: temptation and knowledge simultaneously. He is a “forked branch,” he has walked away from humanity’s path, and that is the reason why he will grieve as his “bones / break” while looking for wisdom. His encounter with his anima did not become what was expected and his experience makes him see that the nature of existence is grieving and that there is only longing for redemption. It is at this stage in the journey that he comes to meet Virginia, a female presence. Indeed, Campbell (2004) states that “not even the remoteness of the desert, can defend against the female presences; for as long as the hermit’s flesh clings to his bones and pulses warm, the images of life are alert to storm his mind” (p. 104). The quester receives two letters from Virginia (his Dear stranger) that takes him to different places, from a church to Virginia’s room, to the countryside, to a kitchen, and to a riverbank. At this point, the quest moves towards the stage of the “trials and victories of initiation” (Campbell 2004, p. 28).

B. Trials and victories of initiation

After the hero survives this test, he is faced with a series of challenges that will comprise the major weight of the journey. The first task is presented when “[o]nce having traversed the threshold, the hero moves in a dream landscape of curiously fluid, ambiguous forms, where he must survive a succession of trials” (Campbell 2004, p. 81). It is also, at this point when the quester “can hear the chime/ of the Old Tower, tinny sacring-bell drifting out / over the city” (p. 27). It is the town’s church bells resonating announcing a new day’s beginning; however, they may also signal death as they toll. The quester is still astray, and he is looking for guidance in this uncertain journey in which life and death are part of one continuum. Furthermore, the persona experiences a transformative experience as the chime becomes the “chyme / of our loves / the peristalsis of the will to love forever / drives down, grain / after grain, into the last / coldest room, which is memory” (p. 27). The chime has morphed into the chyme, semidigested food; in this transformation, the eternal, depicted in the metaphor of the temple and its bells is contrasted with the chyme, a physical reality that gives room to “the maggots/ inhabiting beds old men have died in/ to crawl out” (p. 27).

Subsequently, from this image of the city and the metamorphosis of the “sacring-bell” the hero seems to be taken towards big steps from one place to another, wandering the path; and the first site to visit is Virginia’s room where she is found in fear. She seems to have been possessed by a supernatural being that forces her to draw symbolic elements of wholeness and infinity; however, the horror emerges from understanding that in a road of trials, the persona must recognize that “he and his opposite are not of differing species, but one flesh” (Campbell 2004, p. 89). Virginia cannot accept that what pushes outwards from the inside is part of her nature; perhaps, this is what horrifies her, not accepting her shadow to be able to attain her own self. It is then when she tells the quester:

Dear Galway,

It began late one April night when I couldn't sleep. It was the

dark of the moon. My hand felt numb, the pencil went over the page

drawn on its way by I don't know what. It drew circles and figure-

eights and mandalas. I cried. I had to drop the pencil. I was shak-

ing. I went to bed and tried to pray. At last I relaxed. Then I felt

my mouth open. My tongue moved, my breath wasn't my own. The

whisper which forced itself through my teeth said, Virginia, your

eyes shine back to me from my own world. O God, I thought. My

breath came short, my heart opened. O God I thought, now I have

a demon lover.

Yours, faithless to this life,

Virginia (p. 28).

Virgina fears her own solitude and eternity. Symbolically, she draws “circles and figure eights and mandalas” (pp. 28-29), illustrations that represent the cycle, the infinite8. According to Edinger (1992), the

Self is the ordering and unifying center of the total psyche (conscious and unconscious) … Jung has demonstrated that the Self has a characteristic phenomenology. It is expressed by certain typical symbolic images called mandalas. All images emphasize a circle with a center and usually with the additional feature of a square, a cross, or some other representation of quaternity, fall into this category. There is also several other associated themes and images that refer to the Self. Such themes as wholeness, totality, the union of opposites, the central generative point where God and man meet, the point where transpersonal energies flow into personal life, eternity as opposed to the temporal flux, incorruptibility, the inorganic united paradoxically with the organic, protective structures capable of bringing order out of chaos, the transformation of energy, the elixir of life - all refer to the Self, the central source of life energy, the fountain of our being which is most simply described as God. Indeed, the richest sources for the phenomenological study of the Self are in the innumerable representations that man has made of the deity (pp. 3-4).

Jung considers that the various representation of deities, from the different religions or beliefs, from past and present cultures, were symbolic manifestations of the Self archetype.

This cycle that Virginia envisions unequivocally denotes the cosmic and psychic order that concerns the hero and that may serve as a guide to the journey ahead. However, Virginia seems anguished as many individuals who face moments of solitude for it is not until she “relaxed” and her “heart opened” that she understood that there is a veiled self in every person that needs to be acknowledged to live life at its fullest. Consequently, the hero continues with his path, and after this encounter, he is taken along a river, descending to a place “At dusk, by the blue Juniata” where he is faced with the reality of the destruction of nature and once again his feelings of grief emerge for “a rural America,” the magazine said, / “now vanished, but extant in memory, / a primal garden lost forever…” (p. 28). The natural world as he knew it is gone. It has disappeared. He is confronted with a massive alteration of what he expected; as a result, more difficulties for him to deal with materialize on his path to self-knowledge. As Campbell stresses (2004) “The specific psychological difficulties of the dreamer [in this case the quester] frequently are revealed with touching simplicity and force” (p. 85). Hence, for the persona, the integrity of nature, has been violated as

the root-hunters

go out into the woods, pull up

love-roots from the virginal glades, bend

the stalks over shovel-handles

and lever them up, the huge,

bass, final

thrump

as each root unclutches from its spot.

The roots that live within the soil have been pulled so hard that there is a rumbling sound, like artillery, that echoes in the woods. This is a grieving image of how humanity, in this case the persona, witnesses the devastation of what has given life to him; moreover, it becomes a foreshadowing of his own death unless it is stopped. After experiencing this desolate former paradise in the evening, the persona resumes his journey and he is taken to a room where a concoction is being prepared and the recipe for remaking humankind is being given. Throughout this section, the persona asks for guidance on the uncertainty of his journey and finds the recipe of a potion, by a mystic, that may restore him and humanity to a more primitive state; nevertheless, the only door that seems to unlock for the quester is unconsciousness as this diviner states:

Take kettle

of blue water.

Boil over twigfire

of ash wood. Grind root.

Throw in. Let macerate. Reheat

over ash ashes. Bottle.

Stopper with thumb

of dead man. Ripen

forty days in horse dung

in the wilderness. Drink.

Sleep.

In this section of the poem, the hero is given a recipe for a potion to gain strength. The water should be blue, imagery that is associated with the ocean and consequently with eternity; moreover, the metonymy of the wood, as a representation of the ash tree that has been connected to strength, power and rebirth galvanizes the image as the water boils. Consequently, the water, while boiling, will morph as it will later alter again as it macerates and becomes softer. The stopper of the bottle will be a thumb, illustration that represents humankind’s characteristic that makes him/her different from other species; however, this finger is part of a corpse. Additionally, the recipe alludes to the Bible, the forty days spent by Jesus Christ in the desert; however, in this case, this liquid will ripe for these forty days in excrement, that of a horse. And as bizarre as it may seem, this concoction might look like the last opportunity to gain knowledge, the fragments of intuition that as the quester affirms “(…) mortality/ could not grind down into his meal of blood and laughter” (p. 29). Regarding this moment the persona spends with the sibyl, Campbell (2004) asserts that “It is in this ordeal that the hero may derive hope and assurance from the helpful female figure, by whose magic (pollen charms or power of intercession) he is protected through all the frightening experiences of the father’s ego-shattering initiation” (110). However, the last instruction: “sleep” (p. 29) guides the quester into a state of oblivion, for there seems to be no hope for humankind. Likewise, as he journeys forward his path, the persona is also cautioned and conditioned for

… when you rise -

if you do rise - it will be in the Sothic year

made of the raised salvages

of the fragments all unaccomplished

of years past, scraps

and jettisons of time mortality

could not grind down into his meal of blood and laughter (p. 29).

The persona is notified that after the sleep originated by the potion and only if he rises, it will be when the “fragments” of life lived come to signify a unity and “mortality” would not engulf them in its celebration for these “scraps” would have become a whole. Therefore, “if there is one more love / to be known, one more poem / to be opened into life / [he] will find it here / or nowhere” (p. 29). This is the quester’s time to learn and to gain experience. He will realize the route to follow as he is guided for his “hand will move / on its own / down the curving path” (p. 29) until

a face materializes into your hands,

on the absolute whiteness of the pages

a poem writes itself out: its title - the dream

of all poems and the text

of all loves - “Tenderness toward Existence” (p. 29).

Suddenly, the persona’s object is a poem whose title is “Tenderness toward Existence;” the hero is then provoked to understand life as kindheartedness stirring of the imagination and emotions where he “too, [has] eaten / the meals of the dark shore. In time’s / own mattress” (pp. 29-30). He has experienced grief and loneliness; however, he then wonders if “it can be true - / all bodies, one body, one light / made of everyone’s darkness together? (p. 30). His final enquiry circumscribes each individual on earth. Would it be true that people face different journeys with the same objective? Learning about who they are? Can all these experiences come together and become one? Can people understand the transmutation of the darkness into the metaphor of light?

As the poem develops, the quester will find answers to these and other questions; for example, when wondering about the possibility of others taking this archetypical journey, he hero addresses the future older self of the daughter, because he knows she will be in need of counseling:

And in the days

when you find yourself orphaned

emptied

of all wind singing, of light,

the pieces of cursed bread on your tongue,

may there come back to you

a voice,

spectral, calling you

sister!

from everything that dies (p. 8)

And as he moves forward, he tells her to “learn no reach deeper / into the sorrows / to come” (p. 52). Moreover, in the last section of the book-length poem, he acknowledges the fact that all experiences in life are represented in the symbolism of numbers one and zero: “walk off together/ walk off the end of these pages together, / one creature / walking away side by side with the emptiness” (p. 73), with death. Because humankind should admit that death is part of life, they are one. Since “Lastness / is brightness. It is the brightness / gathered up of all that went before. It lasts” (pp. 73-74).

And then, the quester receives a new missive from Virginia in which she affirms to have been deceived by God as she “[has] no one to turn to because God is my enemy. He gave me / lust and joy and cut off [her] hands” (p. 39). Moreover, she complains about the paradoxes faced in life as she has been endowed with a body but she cannot enjoy it; she should love it but she dreads it; it is alive but also dead, it is a casket; it is spirit and vipers. She abruptly realizes that she is made up of binary oppositions. However, she has not been able to take her journey of self-discovery. Her body has been given to her but somehow, it seems, she has not been able to enjoy it “naturally,” but that is has been conditioned by the institution of religion. This is the reason why she considers a foe her deity. And even when she can communicate her frustration, she cannot understand her reality and requests understanding, for which she would have to embark on her own future journey of self-discovery.

But before answering those former questions, the hero of the poem focuses on himself and answers and replies to the “stranger,” himself, and her reader:

Dear stranger

extant in memory by the blue Juniata

these letters

across space I guess

will be all we will know of one another.

Experience is summarized in the moments lived and gathered in Jung’s concept of humanity’s collective unconscious. And after this epiphany, the quester faces a personal confrontation between the tramp and himself (for he wears the shoes of the tramp) when “the fly /ceases to struggle, his wings / flutter out the music blooming with failure / of one who gets ready to die” (p. 35). In this realm of his world, brightness is absent and there is no struggle when facing death.

For the quester, there will be no more letters between Virginia (the virgin) and him. Virginia’s darkness becomes one with his (the stranger’s); he has been descending through this path and she accompanies him as he wonders if all people’s darkness could conform one light. As the persona proceeds on his passage, there seems to be no movement forward, no solution; and as “the fly / ceases to struggle, his wings / flutter out the music blooming with failure / of one who gets ready to die” (p. 35). Likewise, for him, humankind is trapped in the capitalist fantasy of contemporary life. For the hero, there are individuals who lack caring feelings for others and what people tend to find is “an empty embrace.” Consequently, his experience is desolate and

In the light

left behind by the little

spiders of blood who garbled

their memoirs across his shoulders

and chest, the room

echoes with the tiny thrumps

of crotch hairs plucking themselves

from their spots; on the stripped skin

the love-sick crab lice

struggle to unstick themselves and sprint from the doomed

position -

and stop,

heads buried

for one last taste of the love-flesh (pp. 35-36).

The quester enters a scenario where diseased sexuality is staged and where “love” has no dwelling. The light has been “left behind” and the uncaring sexual encounters are depicted in the verses in the metaphors of the “spiders” and the metonymy of the “crotch hair” the reference to the “love-sick crab lice.” The spiders may very well stand for the veins and arteries system as they resemble these arthropods; the “crotch hair” may represent the unhappy sexual relations women might have experienced in that hotel of “lost light;” while the “crab lice” emphasizes a diseased sexuality that damages individuals. In sum, these images assembled through the metaphors of very little light, the insects that promenade through the scene, the spiders and lice that reflect decay and hence, death, generate in him more anguish on his journey.

The Tramp’s paradoxes are reinforced in the choice of setting, Hotel of Lost Light and when the persona is addressed to take action “If the deskman knocks, griping again / about the sweet, excremental / odor of opened cadaver creeping out / from under the door” (p.37). At this moment of the journey, the hero starts understanding that death is part of two different realities that paradoxically become one. And this awareness is strengthened with the choice of two words that present the same letter but different phonemes: leave, a symbol for dying; and live. Hence, the action requested to be taken is to “tell him, 'Friend, To Live / has a poor cousin, / who calls tonight, who pronounces the family name / To Leave, she / changes each visit the flesh-rags on her bones" (p.37). This double-faced truth, that life and death are intertwined, is explicitly paraded as with life that may come any moment so does death.

In this moment, the persona acknowledges death to be an ever-present reality that seems to mock humanity for when attained it urges to a commencement, just as “the sweet, excremental / odor of opened cadaver” so “Violet bruises come out / all over his flesh, as invisible / fists start beating him a last time; the whine / of omphalos blood starts up again” (p. 37). Death, in the “violet bruises” is echoed at Maud’s birth when “she skids out on her face into light …glowing / with the astral violet / of the underlife” (p. 6); and as in the moment of coming into the world “the stream of omphalos blood humming all about you” (p. 5), it is in the last moment of the person who died that blood stirs and “starts up again” (p. 37). Afterward, “the puffed / bellybutton explodes, the carnal / nightmare soars back to the beginning” (p. 37). The description of the corpse as a distressing image is presented as the blood has stopped circulating through the body; consequently, the latter decomposes and circles to “the beginning:” the “darkness” experienced at the moment of being born. The same sense of loss when coming into the world is undergone when dying for as “they cut / her tie to the darkness / she dies a moment / turns blue as coal / the limbs shaking /as the memories rush out of them” (p. 6).

It is in this gloomy and execrable tone in the poem that the persona encounters a last memory of humanity: the act of speaking and writing. As he asserts, “these words scattered into the future - / posterity / is one invented too deep in its past / to hear them” (p. 37). The hero decides to ponder on the word in which the past and the future are inscribed: “posterity.” Once more, in his quest, two realms mirror life and death so, in this last moment, before leaving the hotel, the speaker affirms to have suffered from “war and madness” in a decaying world without light but has also seen how after death, the bones “tossed into the aceldama” will “re-arise / in the pear tree, in spring” (p. 37) . However, he has found no harmony in the paradox of life and death; and “The foregoing scribed down / in March, of the year Seventy, / on my sixteen-thousandth night of war and madness,/ in the Hotel of Lost Light, under the freeway / which roams out into the dark / of the moon, in the absolute spell / of departure” (p. 37), exactly as he is, facing an oxymoron “and by the light / from the joined hemispheres of the spider’s eyes” (p. 37). The reference to the eyes of the latter instinct are a clue to understand his state of being as the spider’s eyes are an example of transparent hemispheres behind which there is a dark hole without end, exactly as the hero may perceive his life on earth. The persona’s quest for finding meaning in the dichotomy life-death is the perceived contradiction that hunts him. As a result, this becomes the hero’s rationale to continue his descent into the abyss until he finds that “A piece of flesh give[ing] off/ smoke in the field” (p. 41) where “This corpse will not stop burning!” (p. 41). The quester is confronted with his past and humanity’s former pugnacious acts. His recollections of an excruciating past come back as the flashback of a combat episode becomes real as he recollects:

I’d already started, burst

after burst, little black pajamas jumping

and falling… and remember that pilot

who’d bailed out over the North

how I shredded him down to catgut on his strings?

one of his slant eyes, a piece

of his smile, sail past me

every night right after the sleeping pill … (p. 41).

In this flashback, the persona cannot hide the consequences that the experience of war has had on him. The metaphor of “the little black pajamas jumping and falling” echoes the dead of Asians during the Vietnam war; and the horror of memories is discovered when the synecdoche of “his slant eye” and “a piece of his smile” represents the life of thousands of dead soldiers and civilians. As the persona acknowledges, he needs to take pills to sleep, for he continuously remembers the deaths he caused and how he grew accustomed to killing, how he cherished the sound of the firearms and the feeling of power he had as “It was only / that I loved the sound / of them, I guess I just loved / the feel of them sparkin’ off my hands…” (p. 42). The industry of war is presented as a mechanical action that makes people ill. Capitalist society has seen in war a manufacturing business that besides creating jobs for people increases economic growth of nations without considering the destruction and pain it can produce in the world. As a matter of fact, in this section of the poem, human beings are depicted as merciless individuals who end up cherishing the execution of others and the annihilation of themselves.

To continue his journey, the quester is directed to an old memory with his daughter in her room. It is then when he recalls his visits to her room when she “scream[s], waking from a nightmare” and he “sleepwalk[s] / into [her] room, and pick[s] [her] up” to voice what he believes she thinks:

Children, as his daughter, live with death as it were one with life; they do not yet understand, as many old adults, that life encompasses death and death life. But he knows and affirms that he thinks he “exude[s] / to [her] the permanence of smoke or stars” (p. 49), only for a little time “even as / [his] broken arms heal themselves around [her]” (p. 49). His embrace has been torn but his daughter’s presence and life build him stronger. Yet, concern regarding how his daughter may face life and all it represents is depicted in the following verses:

I have heard you tell

the sun, don’t go down, I have stood by

as you told the flower, don’t grow old,

don’t die. Little Maud (p. 49).

The transmutation of the little girl towards different elements of nature, the sun and the flower, worries the persona for he would do anything to keep her alive. It is then when he realizes the origin of this distress: “being forever / in the pre-trembling of a house that falls” (p. 50). The house is a metaphor of the human body and the “pre-trembling” is the life-death continuum that all individuals experience. Life is ephemeral, people can die any moment, at any age, in any place; however, even when a life is terminated, it seems to be restored in the new generations exactly as the persona “can see in [her] eyes / the hand that waved once / in [his] father’s eyes, a tiny kite / wobbling far up in the twilight of his last look: / and the angel / of all mortal things lets go the string” (p. 52). In her eyes the quester can gaze at his father’s life, his, and his daughters; the past, the present, and future together in one final look. And as he places the child, he held up “in the moonlight” (p. 49), “into [her] crib” (p. 52), he now knows that as his father came back in her gaze so will he:

Little sleep’s-head sprouting hair in the moonlight,

when I come back

we will go out together,

we will walk out together among

the then thousand things,

each scratched too late with such knowledge, the wages

of dying is love (p. 53).

For the quester, his perception of the life-death cycle has changed, and it becomes much more than the moment of being born or of dying. His understanding of being on earth has turned into a more optimistic view that will allow him to continue his journey to learn to live a more substantial life and die a more cognizant death for as he states at the end of poem VII what an individual gains with death is love not oblivion or decay.

C. Return or reintegration with (to) society

For this last stage, it is not until the hero has returned to his kin that he will have achieved the challenge and his cycle will have been completed, making him ready to start a new journey. Campbell (2004) affirms that “When the hero-quest has been accomplished…the adventurer still must return with his life-transmuting trophy. The full round, the norm of the monomyth, requires that the hero shall now begin the labor of bringing the runes of wisdom…back into the kingdom of community…But the responsibility has been frequently refused” (p. 167). The quester must be willing to share his knowledge with his community; in the case of the poem, with the readers who have experienced his journey. Thus, to continue with his course and reach his ultimate purpose, the persona moves on and, in the poem “The Call across the Valley of Not-Knowing” is given assistance when “In the red house sinking down / into ground rot, a lamp / at one window, the smarled ashes letting / a single flame go free / a shoe of dreaming iron nailed to the wall” (p. 57). The hero finds a dwelling that seems to be in decay; however, there is light coming out from one window; even if the house may be “sinking down” there is a flame that is released, mirroring a hopeful return.

Moreover, the persona is presented with a setting with “two mismatched halfnesses lying side by side in the darkness” (p. 57). He is resting next to that “mismatched” other who contradictorily matches him and offers him a new being that as the flame in the window provides a promise; as Paz (1995) asserts that “[e]l hombre es el único ser que se siente solo y el único que es búsqueda de otro… el hombre es nostalgia y búsqueda de comunión. Por eso cada vez que se siente a sí mismo se siente como carencia de otro, como soledad9” (p. 341). Paz’s depiction of the hero’s stage is enhanced as the latter caresses his partner, both “in the darkness,” as well as the new being that is coming to help him return and he “can feel with [his] hand / the foetus rouse himself / with a huge, fishy thrash, and re-settle in his darkness” (p. 57). Besides the light at the window there is a new life coming into the world, and the mother figure, an archetype, in the poem takes a leading role in his understanding of the binary opposition life-death.

According to Jung (1970) this psychic pattern is often “associated with things and places standing for fertility and fruitfulness: cornucopia, a ploughed field, a garden… Hollow objects such as ovens and cooking vessels are associated with the mother archetype, and, of course, the uterus, yoni, and anything of a like shape” (p. 15). Fundamentally, this model will exalt growth and fertility; moreover, Jung emphasizes that the qualities associated with it are maternal kindness and understanding, warmth, tenderness, and peace as the hero’s “mismatched halfness” as

Her hair glowing in the firelight,

her breasts full,

her belly swollen,

a sunset of firelight

wavering all down one side, my wife sleeps on,

happy,

far away, in some other,

newly opened room of the world (p. 57).

The blissful image of the woman offers the “mismatched” persona hope in his journey. The moments of fear and despair have morphed into “harmony.” The woman is “happy” and fully aware of the transformations on her body as it gets ready for a fresh commencement in a “newly opened room of the world” (p. 57). However, the route to his return is not deployed of more obstacles for, in order to succeed and achieve his objective, as Campbell (2004) affirms, he has “to pass back and forth across the world division…not contaminating the principles of the one with those of the other, yet permitting the mind to know the one by virtue of the other - is the result of the master. The Cosmic Dancer…does not rest heavily in one spot, but…lightly turns and leaps from one position to another” (p. 196). Unexpectedly, the delight previously experienced with the persona’s “mismatched halfness” is juxtaposed to the irony of life as “Sweat breaking from his temples, / Aristophanes ran off” (p. 57) and made him evoke “that each of us / is a torn half / whose lost other we keep seeking across time / until we die, or give up - or actually find her / as I myself” (pp. 57 - 58). As he continues reminiscing, one day he came across that idealized other, that person that individuals may have dreamed about: the one with the “perfect” smile, or body, or hair, or attitude; but, “for reasons - cowardice, / loyalties, all which goes by the name ‘necessity’ - / left her …” (p. 58).

However, as the persona ponders on this past instant, he realizes that in life there are moments in which time stops to ironically experience it at its fullest. For the quester, the answer to this paradox “must be the wound, the wound itself, / which lets us know and love, / which forces us to reach out to our misfit” (p. 58); it is sorrow that forces individuals into meeting others “and by a kind of poetry of the soul, accomplish / for a moment, the wholeness the drunk Greek / extrapolated from his high / or flagellated out of an empty heart” (p. 59). At his moment of his journey, wholeness is briefly experienced either from the ecstasy of pleasure or through pain until the misfits attain “that purest,/ most tragic concumbence, strangers / clasped into one, a moment of their moment on earth” (p. 58). For the persona, it is after sexual intercourse that an intimate relation may mature. It is not until the sexual act has been completed through penetration, when the two individuals are “clasped into one, a moment of their moment on earth” (p. 58); thus, momentarily, they become one. Afterwards, this transient instant that may have been experienced with the “torn half,” the quester witnesses his “mismatched halfness” as

She who lies halved

beside me - she and I once

watched the bees, dreamers not yet

dipped into the acids

of the craving for anything, not yet burned down into flies, sucking

the blossom-dust

from the pear-tree in spring (p. 58).

There was a moment in the lives of these two individuals when, together, they experienced life and love at its purest form (dreamers) without interacting in a capitalist economy of the Western world: they did not crave for anything material nor did they want to take advantage of others. Experiencing life became their ultimate aim. At this memory, his “mismatched halfness” becomes a beacon as they “lay out together / under the tree, on earth, beside our empty clothes, / our bodies opened to the sky, / and the blossoms glittering in the sky / floated down” (p. 59). They are in communion with nature with nothing to hide for now he knows who they truly are “and the bees glittered in the blossoms / and the bodies of our hearts / opened / under the knowledge / of tree, on the grass of the knowledge / of graves, and among the flowers of the flowers” (p. 59). Being at this setting, under the shadow of this tree, “the mythological world axis, at the point where time and eternity, movement and rest, are one” (Campbell 1991, p. 172), and with this understanding, he is now “explicitly commissioned to return to the world with some elixir for the restoration of society, the final stage of his adventure is supported by all the powers of his supernatural patron” (Campbell 2004, p. 170).

Indeed, the persona finds himself in a natural environment that mirrors the paradox of humanity and so he affirms:

I come to a field

glittering with the thousand sloughed skins

of arrowheads, stones

which shuddered and leapt forth

to give themselves into the broken hearts

of the living,

who gave themselves back, broken, to the stone (p. 65).

In this section of the poem, he finds himself in a setting that shimmers with dead peels, a place where “arrowheads” have cast off their skins, dying to the past but simultaneously living in their descendants who are also broken. As the persona moves forward, he “close[s] [his] eyes” (p. 65) and is situated, as in a dream, “on the heat-rippled beaches / where the hills came down to the sea / the luminous / beach dust pounded out of funeral shells” (p. 65). He is positioned in the boundary of two symbolic realms, the land and the sea where he can see the “funeral shells / them living without me, dying, / without me, the wing / and egg / shaped stones” (pp. 65-66). Stones, inanimate objects representing the sublime and the terrestrial, that belong to the sphere of “that wafer stone / which skipped ten times across / the water, suddenly starting to run as it went under” (p. 66). Particularly significant is the cyclical movement of the water and its representation of “zeroes,” where you find the beginning and the end of the infinite, the life and death continuum as “the zeroes it left, / that met / and passed into each other, they themselves / smoothing themselves from the water…” (p. 66). It is then when the persona confirms the knowledge acquired when he affirms

I walk out from myself

among the stones of the field,

each sending up its ghost-bloom

into the starlight, to float out

over the trees, seeking to be one

with the unearthly fires kindling and dying

in space - and falling back, knowing

the sadness of the wish

to alight

back among the glitter of bruised ground,

the stones holding between pasture and field,

the great, granite nuclei,

glimmering, even they, with ancient inklings of madness and war (pp. 66-67).

In this passage of the poem the hero seems to leave his body and become a spirit because he “walk[s] out form [him]self” encountering the “ghost-bloom” that the stones project. As he keeps walking to reach his destination, the stones cast shadows of death that intersect with the action of blossoming in the sky and touching the earth through the trees. In this moment of the journey, he wishes to vanish with the lights in the sky; however, the quester realizes that he must not evade the path to be taken even when humanity has not evolved regarding “madness and war.” The scenario may have not been what he expected but it is what it must be. The persona needs to complete his journey and for this he must enter hell, action that is taken when the ground that is sore offers a path that “opens / at [his] feet” (p. 67), and not being confused anymore, he “go[es] down / the night-lighted mule-steps into the earth. The persona continues his descend to be able to, later, reach higher to complete his learning.

However, this dive into the trail seems not to be done in complete darkness or solitude as “the night-lighted mule-steps into the earth/ the footprints behind me / filling already with pre-sacrificial trills / of canaries” (p. 67). Remarkably, he is led into the path that is dark and concurrently lighted and mule steps precede him while the tracks left behind are filled with the song of birds that “go down / into the unbreathable goaf / of everything [he] ever craved and lost” (p. 67). The hero realizes that the tracks he leaves behind are immediately filled with warbles; as he states, he is now aware of his advancement and there are moments when he feels unable to breathe when thinking about his desire for acquiring material objects. This same motif has been felt in a previous section of the book-poem when he ponders on his former desire for consuming goods, deed that caused him more grief than joy as they (he and his spouse) were “dipped into the acids / of the craving for anything.” Kinnell, in this section, meditates on how society and its machinery of progress have made humankind believe that acquiring goods will make them happy; however, there will be a moment of awareness when the poem’s hero realizes that what these material objects are impractical in the quest for self-knowledge.

Moreover, the image of decomposition succeeds in letting the persona and the reader reconsider and reflect on the futility of mass consumption. This idea is also examined when ironizing many of the social conventions accepted to inflict pain on others through the machinery of war and consumerism in section VI of the poem. In section IX, he encounters “An old man, a stone / lamp at his forehead” (p. 67) who “stirs into his pot” and “salts / it all down with sand / stolen from the upper bells of hourglasses” (p. 67). At this moment, when he acknowledges that as he has moved on, there seems to be “Nothing. / Always nothing. Ordinary blood / boiling away in the glare of the brow lamp” (p. 67); nevertheless, as he ponders on his experience, he asserts: “And yet, no, / perhaps not nothing. Perhaps / not ever nothing” (p. 67). He confirms that even when an individual may experience loneliness, it may not be so because that instant may transform into an gate to “find myself alive / in the whorled / archway of the fingerprint of all things, / skeleton groaning, / blood-strings wailing the wail of all things” (p. 68). The metaphor of the “whorled archway” to indicate the axis of movement, towards death or life, prompts the speaker to consider his inner structure as “The witness trees” that “blaze themselves a last time” (p. 21) are transmuted into those that “heal / their scars at the flesh fire” (p. 68) and

the flame

rises off the bones,

the hunger

to be new lifts off

my soul, an eerie blue light blooms

on all the ridges of the world. somewhere

in the legends of blood sacrifice

the fatted calf

takes the bonfire into his arms, and he

burns it (p. 68).

The persona in the poem has conquered his weaknesses and learned throughout his journey. In this moment, the fire that has been present as a consuming element “rises off the bones” and an uncanny light shines around the world. This blue light is reminiscent of “the blue / flower opens” (p. 4) when baby Maud is born and once “she dies / a moment” (p. 6) as she is being delivered; moreover, it is reminiscent of the blue water of the Juniata that has witnessed life as well as death and of the blue spittle from which he regains strength to “crawl up” (p. 68). Likewise, it foreshadows the “blued flesh,” in the last poem, that reminds the hero of the juxtaposition of the life-death opposites and their beauty and horror. Regarding the attainment of this insight, Paz (1995) affirms that “[r]egresar a la muerte original será volver a la vida de antes de la vida, a la vida de antes de la muerte: al limbo, a la entraña materna10” (p. 199).

Unquestionably, it is after this moment when the persona completes the journey as he finds the bear scratching “the four-footed / circle into the earth” (p.71): being born, growing up, reproducing, and dying. Unexpectedly, the persona recognizes that he is a creature, like any other in the world but in a different position, “He sniffs the sweat / in the breeze, he understands / a creature, a death-creature / watches from the fringe of the trees” (p. 71). The bear then “get[s] up, eat[s] a few flowers, trudge[s] away, /all his fur glistening / in the rain,” (p. 72) giving the hero room to embrace the birth of Fergus as “he came wholly forth / I took him up in my hands and bent / over and smelled / the black, glistening fur / of his head” (p. 72). Unequivocally, Kinnell’s use of natural imagery enriches the hero’s path as the reflection of the son on the bear and the metaphor on how the “empty space / must have bent / over the newborn planet / and smelled the grasslands and the ferns” (p. 72) leads him into a fresh beginning of a new life on earth. The quester seems to move backwards to the birth of his daughter Maud but if this movement were to be real, there is a distinction: now he is aware that “[L]iving brings you to death, there is no other road” (p. 73) and viceversa; or as Paz (1995) declares “La muerte es intransferible, como la vida11” (p. 189). Moreover, this same scholar asserts that

Para los antiguos mexicanos la oposición entre muerte y vida no era tan absoluta como para nosotros. La vida se prolonga en la muerte. Y a la inversa. La muerte no era el fin natural de la vida, sino fase de un ciclo infinito. Vida, muerte y resurrección eran estadios de un proceso cósmico, que se repetía insaciable. La vida no tenía función más alta que desembocar en la muerte, su contrario y complemento; y la muerte, a su vez, no era un fin en sí; el hombre alimentaba con su muerte la voracidad de la vida, siempre insatisfecha.12 (Paz, 1995, p. 190).

As Paz discusses, the quester understands that for life to be, there has to death; paradoxically, even when being opposites, they are also shares of a whole. He recognizes that this journey has been his own and that its purpose has been to learn to live in a seemingly paradoxical world that is not. Individuals are often perplexed at the discovery that one ends leads to a beginning or as T.S. Eliot, in his poem “East Coker13” said “[i]n my end is my beginning” (p. 14). This endless continuum is present in people’s lives and when the polarities are both accepted as one, as the hero realizes, the experience on earth changes positively. After this realization, the quester understands that this journey of self-discovery has made him embrace the emptiness that scared him when starting it. Furthermore, he realizes that “Lastness / is brightness. It is the brightness / gathered up of all that went before,” and this dichotomy in which humankind dwells (as Sancho the classical fool and Fergus an Irish heroic mythical figure) has to be accepted to live a more fulfilling life so “Sancho Fergus! Don’t cry! / Or else, cry” (p. 75).

Conclusion (s)

This study analyzed the monomyth and its different phases; as a result, the quest took the persona from the first stage, the separation or departure, to that of trials and victories of initiation to the final stage of the return and reintegration with society which is of uttermost importance to achieve knowledge. As the quester moves forward in his journey, he doubts, fears, questions, and learns that the binary oppositions life and death are part of the same continuum and that they walk hand in hand. For the persona, the journey was not an easy process because coming to this understanding involved the negation of what had been previously learned. Thus, accepting this fact produced, in the first stages, grief and fear in the quester. However, in the final stage, he learns that sooner or later death will reach his life and that he is a sibling of “everything that dies” (p. 8). For the hero, the moment of death transmutes into life and viceversa.

The major influential studies on Galway Kinnell’s The book of nightmares discuss the leading idea of the book-poem as well as its symbols and images in general. Scholars and critics have predominantly questioned and discussed this poet’s “obsession” with life cycles and death as well as the use of nature and natural imagery in his work. Nonetheless, though vastly associated to these arguments, previous studies have vaguely considered the reading of The book of nightmares from both, a mythical and archetypal stance. Therefore, this study intends to fill this theoretical gap, consequently, enriching the analysis of the text and offering a fresh reading of and through, mainly, Jung and Campbell’s theoretical frameworks.

For Campbell (2004) “The effect of the successful adventure of the hero is the unlocking and release again of the flow of life into the body of the world” (p. 32), act that is achieved in the poem with the release of new force represented in the birth of a baby. This new being is a new “flow of life” that becomes part of this world to keep life’s continuum and with it a new individual who will, one day, start his own quest. Regarding this archetypical task that most people go through literally or metaphorically, Jung (1956) affirms that

The finest of all symbols of the libido is the human figure, conceived as a demon or hero. Here the symbolism leaves the objective, material realm of astral and meteorological images and takes on human form, changing into a figure who passes from joy to sorrow, from sorrow to joy, and, like the sun, now stands high at the zenith and now is plunged into the darkest night, only to rise again in a new splendor (p. 171).

In these words, Jung describes the fluctuating essence of humankind, and the quester in the poem is no different. He moves from pain to bliss and spends dark moments in hell to finally encounter a pleasing “skinny waterfalls, footpaths / wandering out of heaven” (p. 71). In sum, in this research paper, it has been demonstrated how the persona completed the mythological voyage of the hero and for this task he faced its three macro stages: separation, initiation and return. Consequently, at the end of the journey he is among his peers a “different” man for he has accomplished his task.