Introduction

Everyone may agree that teaching English as a foreign language (EFL) to a homogenous population has several strengths. However, the opposite case occurs while meeting the needs, wants, and lacks of a highly heterogeneous group of thirty learners. The reasons for this challenge may involve: registering a course as a mere academic requisite, not being interested in the target language, having received negative comments towards the course in the past, lacking the basic skills to start a high intermediate reading course, or even not passing the diagnostic or the proficiency standardized tests, thus, taking it in a regular semester. On top of these factors, having at least thirty students from various university majors certainly represents a challenge as many students take the course either at the beginning or at the end of their majors. Thus, some are used to reading academic publications in the target language; others hardly read in English or are not even interested.

Although it is not appropriate to generalize, this is part of the teaching context that surrounds the course LM-1030 Reading Comprehension Strategies at the University of Costa Rica, based on the writer’s experience. All these factors aforementioned correspond to a challenge, especially to novice instructors. This situation may worsen when many students belong to majors in which they hardly ever interact or work in groups during class time. Integration is not easy as most students prefer to work individually. So, this study aims at observing the implementation of group work in a reading strategies course to foster cooperative learning and participation. Given the fact that this group of students is highly heterogeneous, the researcher implemented three instruments to gather his students’ perceptions in regard to intensive exposure to group work throughout the entire semester. According to the course syllabus, the level of this reading strategies course is high intermediate.

Review of Literature

The Notions of Group and Group Work

Individuals function better in constant interaction and cooperation within others; this is also constructive in second language education. Students with limited knowledge in the target language certainly benefit from the assistance of their peers, especially in a reading strategies course where some learners lack high-intermediate vocabulary, for example. In order to achieve this, implementing intensive group work with a highly heterogeneous population is valuable, helpful, and functional. Before explaining what group work consists of, it is important to define the concept of group per se. Brown (as cited in Dörnyei, 2003) pointed out that “a group exists when two or more people define themselves as members of it and when its existence is recognized by at least one another” (p. 12). Thus, these individuals may bring valuable background knowledge, interests, expectations, or professional experiences to the classroom setting. To achieve this in an EFL context, language instructors “need to encourage in their own classrooms a sense of belonging to a team or community, which has implications both for the learning group, and also for the school as a whole” (Williams and Burden, 1997, p. 79).

To some extent, many language learners may experiment some difficulties in adapting to a new learning environment. Thus, a certain level of anxiety may arise if they do not possess basic knowledge in the target language compared to their peers’ as they probably come from bilingual or private schools. In regard to this, (Dörnyei and Murphey) have listed some of the most essential individuals’ feelings while encountering a new group:

“general anxiety,

uncertainty about being accepted,

uncertainty about their own competence,

general lack of competence,

inferiority,

restricted identity and freedom,

awkwardness,

anxiety about using the L2,

and anxiety about not knowing what to do (comprehending)” (2003, p. 15).

So, what can instructors do to minimize their students’ level of anxiety and uncertainty? Indeed, the constant implementation of group work may foster learners’ cooperation in order to function better during class exercises, tasks, and even evaluations (quizzes or final project presentations). In relation to those classes or courses where students have dissimilar skills and proficiency levels, Stevens (as cited in Harmer, 2015) explained that “in its simple form, is where teachers adapt their approach for different students so that the entire class have the chance to perform to the best of their ability” (p. 143).

In order for a group to be successful, there is a series of qualities that should be present. For instance, Hadfield (as cited in Williams and Burden, 1997) mentions some principles of effective groups of individuals in cooperative settings:

“Members have a definite sense of themselves as a group.

There is a positive, supportive atmosphere: members have a positive self-image which is reinforced by the group […].

Members of the group listen to each other and take turns.

The group is tolerant of all its members; members feel secure and accepted.

Members co-operate in the performance of tasks and are able to work together productively.

The members of the group trust each other.

Group members are able to emphasize with each other and understand each other’s points of view even if they do not share them” (p.195).

Group work involves a students’ form of participation and cooperation to carry out a given activity (controlled and semi-controlled exercises as well as tasks or interactive games) successfully in an appropriate amount of time; this should be followed by teacher’s positive feedback or follow-up corrections. In terms of group work and the completion of tasks, Carter and Nunan (2001) clarified that

[t]he types of tasks in which learners engage and the number of participants in a task also affect learners’ participation. Studies have been conducted on learners’ participation involving pair work, group work and the whole class. It was found that compared to teacher-fronted interaction in whole class work, both pair work and group work provide more opportunities for learners to initiate and control interaction, to promote a much larger variety of speech acts and to engage in the negotiation of meaning (p.122).

So, some of the key features of group work will include the level of negotiation of meaning/content in which students are involved in. This takes place, for example, with information-gap activities as well as WebQuests to share or complement information and complete the task at hand. Compared to pair work, for example, there are benefits and weaknesses of group work, especially in heterogeneous classes. For instance, Harmer (2015) has summarized some of them in the chart below:

Table 1 Advantages and Disadvantages of Group Work

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

| 1. "It dramatically increases the talking opportunities for individual students. | 1. It is likely to be noisy. |

| 2. There is also greater chance of different opinions and varied contributions | 2. [Some students] prefer to be the of the teachers attention. |

| 3. It encourages broader skills of cooperation and negotiaition than pair work | 4. Students find themselves in uncongenial groups. |

| 4. It promoter learner automony by allowing the students to make their own decisiones. | 5. [Some students] are ássiva whereas others many dominate. |

| 5. Students choose their level of participation more readily. | 5. Groups can take longer to organize than pairs".(p.182) |

Source: (Hammer, 2015, p.182)

Motivation and Foreign Language Learning

Undoubtedly, motivation is an aspect that fosters second and foreign language acquisition. Although many students take a language course to meet their academic needs, linguistic lacks, and individual wants, being motivated is a key factor that facilitates this teaching-learning process. To define this term, Williams and Burden (1997) view motivation from a cognitive and constructivist perspective as the “state of cognitive and emotional arousal, which leads to a conscious decision to act, and which gives rise to a period of sustained intellectual and/or physical effort in order to attain a previously set goal” (p. 120). However, in this cognitive and intellectual path, there are several elements that intermingle and influence the level of success at the moment of acquiring a second language; some of these may be internal depending on the learners’ cognitive and affective factors (i.e., learning styles, the affective filter, anxiety, and so on) or external in terms of the benefit from receiving formal instruction or the educational and methodological essentials (i.e., teaching methods or course materials).

Defining motivation is not easy as it is composed by other elements that influence language acquisition. In general, Gardner (1985, cited in Williams and Burden, 1997) defines motivation as “a combination of effort plus desire to achieve the goal of learning the language plus favourable attitudes towards learning the language. Other factors, such as attitude towards the learning situation and integrativeness can influence these attributes” (p. 116). Indeed, there are internal (i.e., learning styles and anxiety) and external elements (i.e., studying in a foreign country where the target language is spoken) that will eventually determine the level of success at the moment of acquiring a second language.

These elements are also related to intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in language learning. In the case of intrinsic motivation, “the reason for performing the activity lies within the activity itself” while extrinsic motivation deals with external benefit that derives from performing that activity (Csikszentmihalyi and Nakamura, 1989, cited in Williams and Burden, p.123). On the other hand, a study conducted by Mora, Trejo, and Roux (2010) illustrates the concept of extrinsic motivation; in this case, the researchers studied the motivational factors of a group of ESL students and determined that that some of the participants “chose to study it for a variety of reasons from meeting the imagined demands of potential employers to having access to what they believe are reliable and updated sources of knowledge” (p. 13). So, to distinguish between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, Harter (1981, cited in Williams and Burden, p. 124) listed various features at the end of a continuum that summarize the different dimensions of motivation:

Table 2 Characteristics of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation in Language Learning

| Instrinsic | - | Extrinsic |

| 1.Preference for challenge | - | Prefeence for easy work |

| 2. Curiosity /interest | - | Pleasing teacher / getting grades |

| 3. Independent mastery | versus | Dependence on teachers judegmente about what to do |

| 4. Independent judgment | - | Reliance on teachers judgment about what to do |

| 5. Internal criteria for success | - | External criteria for success |

Source: Harter (1981, cited in Williams and Burden, p. 124).

In relation to the elements mentioned before, one can conclude that to motivate language learners is always a challenge. They all have individual differences in terms of their proficiency level, background knowledge, expectations towards the course, and personal interests. Davies and Pearse (2000), for example, classify English learners into three categories: (1) highly motivated students who love the language and its culture; (2) reluctant students who do not want to study the language but know it will be eventually useful, though; and finally, (3) those who lack motivation to learn and use the language and feel they are taking a given language course because it is an obligation (p.14).

Despite having different levels of motivation or the type of learner, the instructor’s challenge is always to implement appealing materials to maintain and increase learners’ motivation throughout the course and raise awareness on the practical use of the target language in real contexts. Regarding additional factors that influence motivation, the same source (Davies and Pearse, 2000) makes a distinction between tangible (environmental and material aspects) and intangible conditions (class participation and motivation towards the language) in language learning; although both are important constraints, language teachers should be aware that the intangible aspects have a bigger impact on second language acquisition at the moment of motivating students.

Dörnyei (2001) highlighted the importance of group work to encourage learners’ motivation in the EFL classroom:

“Cooperation fosters class group cohesiveness: despite all the members’ dissimilarities, there should be a sense of unity and rapport.

Group work fosters an expectancy of success: all the group members strive hardly to succeed at completing the task at hand. However, this sense of competition is argued as it contrasts with the sense of cooperation in the classroom, though.

Cooperative team work achieves a rare synthesis of ʻacademicʼ and ʻsocialʼ goals: as these two types of goals intermingle, there is a clear-cut purpose of implementing group work.

In cooperative situations there is a sense of obligation and moral responsibility to the fellow-cooperators. Learners are all responsible for completing the task even though their motivation may not be high.

Cooperation occurs as a means of each individual’s unique contribution.

Cooperation involves a positive emotional tone. Thus, working in groups may be less stressful than other teaching formats.

Cooperative teams are autonomous: as the instructor is not able to work with every single group, learner autonomy is fostered.

Success leads to group satisfaction.

Cooperative situations increase the significance of effort (p.100-101).”

Learning Strategies

There has been a major interest in knowing how successful learners acquire a second language. To accomplish this, good language learners make use of a series of techniques or strategies to facilitate the acquisition and use of a second language. Stern (cited in Griffiths, 2015) explains that a good language learner employs specific strategies such as “experimenting, planning, developing the new language into an ordered system, revising progressively, searching for meaning, practicing, using the language in real communication, self monitoring, developing the target language into a separate reference system, and learning to think in the target language” (p.426).

Although there is a vast number of definitions and classifications of learning strategies, these techniques share some basic characteristics. Wenden (cited in Alderson, 2000) indicates that language-learning strategies have the following features:

“They refer to specific actions or techniques

Some of them are observable.

They are problem-oriented.

They contribute directly and indirectly to language learning.

They may be consciously deployed or remain below the level of consciousness.

They are amenable to change” (p.308).

Other experts classify language-learning strategies in terms of cognition, communication, and socialization. For example, Rubin (Oxford, cited in Alderson, 2000) indicates that there are cognitive strategies (those that emphasize on how the language is used by means of classroom tasks) as well as meta-cognitive strategies which deal with the reflection of the learning process itself; in addition, there are also communication and social strategies (p. 308). Regarding this classification, the Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (Griffiths, 2015, p. 427) has listed and exemplified learning strategies as follows:

Table 3 Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL)

| Strategy | Definition | Example |

| 1.Memory | How learners recall languaje | Using mnemonic devices |

| 2. Congnitive | How to use lenguaje material | Paraphrasing |

| 3. Compensation | How to make up limited content | Guessing meaning |

| 4. Meta-cognitive | How to manage the learning process | Peflecting on mistakes |

| 5. Affective | How to lower the affective filter | Trying to relax |

| 6. Social | How to interact with other peers | Clarifying doubts |

Source: Griffiths, 2015.

Methodology

The Target Population

The target group consisted of thirty students who registered the course LM-1030 Reading Strategies I at the University of Costa Rica. They attend two lessons each week (6 hours, 3 hours each). A virtual classroom is used to reinforce the material seen each week.

3.2 Course Packet and Course Materials

This group used two types of course materials: the main textbook was Longman Academic Reading Series 4: Reading Skills for College (2014). As time is an important constrain, all the groups covered eight chapters (Chapters 1-5 and 7-9). Additionally, there was a supplementary booklet which contains the theoretical foundations behind each reading strategy. Students also use a monolingual or bilingual dictionary in its digital or printed edition, being the printed one mandatory during evaluations.

In relation to this, this is the content of the supplementary course packet: an overview of the reading process, background knowledge (formal, linguistic, and content), definitions of reading strategies (Chapter 1), a summary on verb tenses (Chapter 2), the passive voice (Chapter 3), morphology (Chapter 4), parts of speech (Chapter 5), word functions: nominal, adjectival, verbal, and adverbial (Chapter 6), topic, topic sentence, main idea, and supporting details (Chapter 7), typographical clues and punctuation marks (Chapter 8), rhetorical patters (Chapter 9), implicit and explicit information (Chapter 10), facts and opinions (Chapter 11), and writer’s tone and purpose (Chapter 12).

3.3 Brief Description of the Course and its Methodology

LM-1030 Reading Strategies does not have any academic requisites or co-requisites. The main purpose behind this course is to provide students with the necessary reading strategies in order to comprehend various types of texts and genres, being the case of authentic newspaper articles or academic readings. Although the main focus of the course is strategy training, there is a general review of grammatical structures during the first five weeks of classes depending on how each instructor prepares his or her tentative timetable. A grammar component is necessary as this facilitates reading comprehension, especially with low-beginners.

The main objective of this course indicates that “by the end of the course, the students will be able to interact actively with texts of different contents and rhetorical patterns applying the appropriate reading skills to understand, analyze the content of the texts and also to take a position about the author’s perspective” (taken from the Course Syllabus, 2018). The table below includes both the course specific objectives and all the reading strategies seen throughout the semester:

Table 4 LM-1030 Specific Objectives and Reading Strategies

| Specific objetives | Reading Strategies |

| 1. Apply the cultural and formal patters to identify is genre. | Apply the scanning and skimming techniques using typographical keys. |

| 2. Make predictions its genre. | Discriminate the lexical forms from the non lexical. |

| 3. Guess the meaning of unknown words by their context. | Guess the meaning of unknown words by context. |

| 4. Recognize when and how to use the dictionary | Incorporate (internalize) new vocabulary. |

| 5. Identify rhetorical patterns. | Use the dictionary efficiently. |

| 6. Discriminate main ideas from minor details. | Ignore structures to get the main idea. |

| 7. Respond critically to a text thorough: | Discriminate the secondary ideas/details from de main idea. |

| - | 8. Identify thw synoyms and antonyms that help the reader understand a main idea. |

| a. an evaluation of the authors perpective. | 9. Identify rhetorical patterms. |

| b. inferences fromt explicit and implicit infromation. | 10. Apply the detail technique. |

| c. recognition of ideas (main and secondary) | 11. Organize the content information in conceptual maps. |

| d. recognition of ideas. | 12. Summarize and paraphrase the text |

| e. Judgments about the information read. | 13. Identify the authors purpose in the text. |

| - | 14. Determine the authors tone in the text. |

Source: List of objteives and strategies taken from the Course Syllabus.

With reference to the methodology of LM-1030, this course follows an intensive approach to reading comprehension. Unlike other reading comprehension courses, this does not focus on extensive reading as students are not asked to read novels or large texts. Regarding the concept of intensive reading, Nuttall (2000) fully explained the concept of intensive reading:

Intensive reading involves approaching the text under the guidance of a teacher […] or a task which forces the student to focus on the text. The aim is to arrive at an understanding, not only of what the text means, but of how the meaning is produced. The ʻhowʼ is as important as the ʻwhatʼ, for the intensive lesson is intended primarily to train strategies which the student can go on to use with other texts. […] With in intensive reading, a further distinction can be made between skills-based and text-based teaching. In a skill-based lesson, the intention is to focus on a particular skill, eg inference from context. In order to develop this, a number of texts may be used, each offering opportunities to practice the skill. […] A text-based lesson, on the other hand, is what we usually have in mind when referring to an intense reading lesson: the text itself is the lesson focus, and students try to understand it as fully as necessary, using all the skills they have acquired (p. 38).

LM-1030 focuses primarily on skill-based lessons. By doing so, each reading strategy should be practiced with a reading text taken from the course textbook. There is a correlation between the supplementary booklet with the topics of the reading textbook. So, instructors explain and exemplify all the reading strategies listed in the supplementary course packet with a wide range of classroom dynamics and tasks. Then, students carry out the exercises from the course textbook. Additional reading texts should be authentic and updated, especially at the moment of preparing both reading comprehension exams. According to the course methodology, “the dynamics of the class includes activities focused on the exposition, the exemplification, the practice, the theoretical evaluation, the use of essential skills and strategies to the process of reading through the projects” (taken from the Course Syllabus, 2018).

The Target Course and the Practicality of Group Work

For group work to be successful, there are several aspects that instructors should bear in mind while planning their lessons: (1) preparing the activity, (2) grouping techniques, (3) seating arrangement, (4) setting the task, and (5) giving positive feedback. To begin, professors should determine whether or not group work is pertinent and feasible for a given task, i.e., an information-gap activity or a WebQuest (when mobile devices and computer-lab are available). Should students carry out a task individually, in pairs, or in small or large groups? In the case of completing short or controlled exercises, it is not relevant to implement team work as the professor will revise its answers with the whole class. On the other hand, one should also plan how students will distribute around the class and form groups with their peers. Ramírez (2005) suggests to divide the entire class based on random patterns such as students’ birth dates, scrambled pieces of a few puzzles, categories of objects (pictures or even pieces of candy) or topics, synonyms or antonyms, phonetic sounds, scrambled sections of proverbs, or words with several definitions. By doing so, students will always form groups and join people they have never worked with before. A possible disadvantage of this is that low-beginners may end up working together.

Then, the next step is to place students in a way that seating arrangement would facilitate learners’ and the teacher’s circulation to monitor or check students’ progress. Since most classrooms contain separable tables, it is the teacher’s decision to move them in a particular way. Even though students may prefer to work in small groups (three or four members each), one must consider that “the students may not want to be stuck with the same three or four students forever” (Harmer, 2015, p. 180). In a large class such as LM-1030, the writer has had a positive experience splitting the desks in two big parts. Each part has two rows of sixteen desks overall; one desk will be placed in front of the other to form four groups of four.

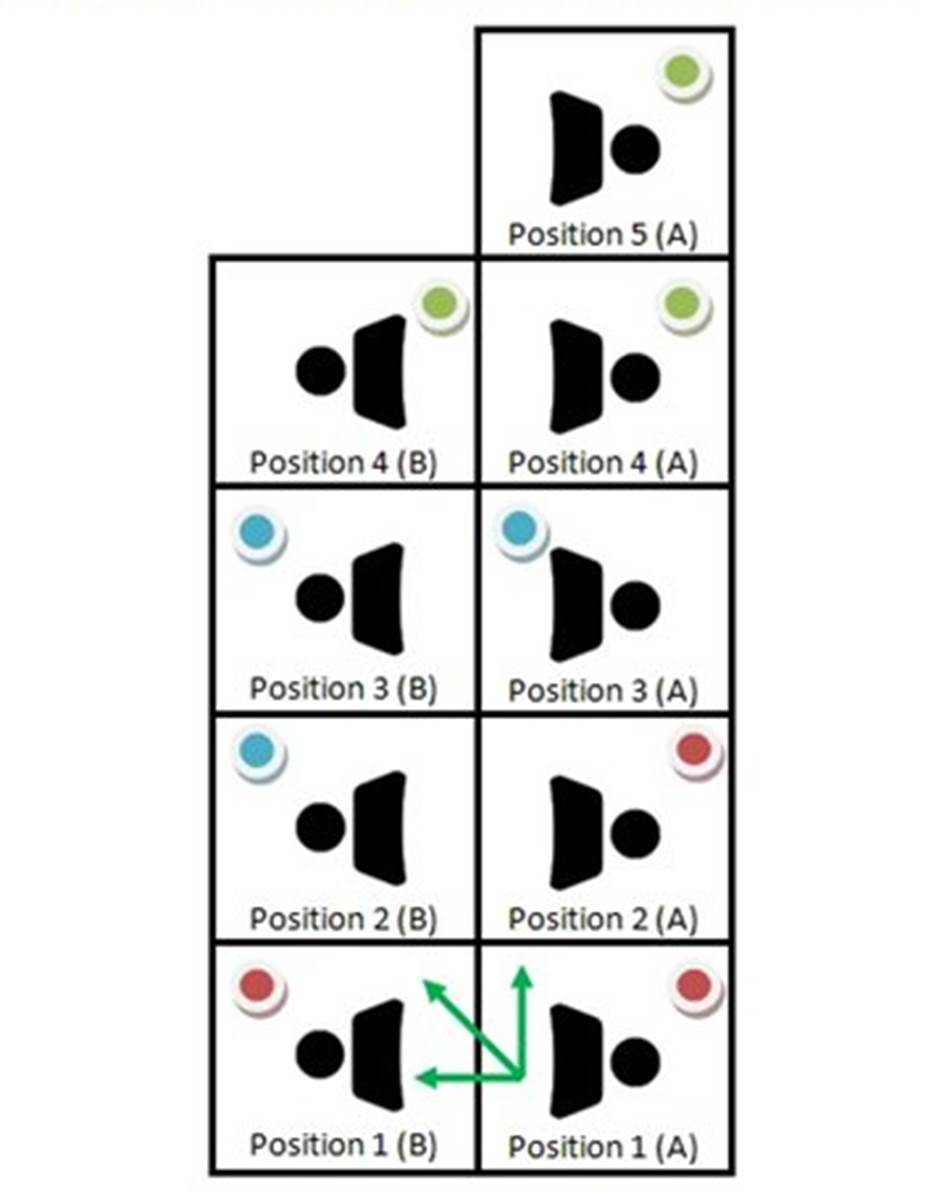

In this way, students may work with different people without dragging the tables regularly (see Figure 1). The figure shows only one section of the entire class and how students can easily work in pairs (either with the person in front / next to), in trios (the colored dots indicate this distribution), or in groups of four. By following this seating arrangement, there is a time-saving consideration as the teacher can arrange the desks a few minutes before the class starts. In terms of grouping, the teacher may randomly indicate where they have to sit; thus, they will work with different classmates. This is a practical form of seating arrangement in such large groups.

There is a wide variety of reading-comprehension activities that can be easily adapted to be carried out in small groups, thus, encouraging cooperation and even competition. Approaches to language teaching promote collaboration, but there are cases in which competition may increase motivation. Dörney and Murphey (2003) explained that “competition can be a kind of collaboration when people unite in an effort to win;” in other words, “intergroup competition” is a desirable goal instead of individual competition (p.25). One example of this is the use of students’ mobile phones as a voting tool in reading activities. Students may take advantage of Kahoot or Socrative as game-based tools in small groups.

Concerning the reading strategies covered in this course, the table below illustrates a series of group activities that correlate with the reading strategies for the first part of the course:

Table 5 List of Activities for the Cource LM-1030

| Reading Process | Reading Strategies | Type of activity |

| Pre-reading | Scanning | Students scan details from a seris of classified ads is small groups. |

| - | Skimming | • Three students look for specific details in a jigsaw task (sections A,B, ad C). |

| - | Guessing meaning in context | • By using the cell phone as a voting decive, students select the correct definition. |

| - | Typographical clues | • An impromptu presentation in groups |

| - | Morphology | • Learners play a board gema to form new words based on root words and affixes. |

| While-reading strategies | Parts of speech | • A. Students play mad libs in groups. Then, they read the phrsal template words stories ouy loud. |

| - | - | • B. Students solve a rebus with the correct parts od speech. |

| - | - | • C. Fous students stand in lin as a member reads a text posted in the wall and looks for a given word to fit the context. |

| - | Pronoun referents and expletives | • In groups, learners complete a corssword puzzle with pronoun antecedents. |

| - | Word Funtion | • As students circulate around the class, they read a series od cards and determine the function of target words and phrases. |

Source: Own work.

To give clear instructions is essential. If necessary, the instructor may model or exemplify a desired type of outcome. Then, there is an opportunity to assign specific roles to group members. Regarding this, Dörney and Murphey (2003) distinguish between task roles versus maintenance roles during group work; while the former will facilitate the process of completing the task (e.g., coordinator, evaluator, secretary or recorder), the latter may deal with the affective component (e.g., encourager, harmonizer, feeling expresser) of the process (p.114-115). Finally, after having carried out the task, it is the instructor’s role to revise the given outcome and provide immediate and positive feedback on it. Additional teacher’s roles include facilitator or motivator as well.

3.5 Sample Group Activity: Designing a Short-Term WebQuest

A WebQuest is a research-based group activity that illustrates how such population may implement the reading strategies seen so far in an interactive, meaningful, and collaborative form. This section includes a short-term WebQuest because it can be completed in two different lessons, as opposed to long-term WebQuests that take several lessons or even weeks. By doing so, learners investigate and focus on content while conducting this inquiry-oriented task. Learners will implement various reading strategies such as skimming, scanning, summarizing, paraphrasing, guessing meaning in context, among others. With this group activity, students work in groups of four members so that each person investigates on one specific aspect related to one major topic. This idea is to later complement the information with data collected by the rest of the members. Students may use the computer laboratory or explore websites with their cell phones, but this is not very practical, though. Thus, the following is a sample WebQuest used in this course. This WebQuest includes the five main sections of a WebQuest framework listed by Thombs, Gillis, and Canestrari (2009, 27-30):

Basic Components of the WebQuest Framework

a. Introduction: For a WebQuest to be successful, instructions must contextualize the activity with one of the course units. In this case, the WebQuest covers one of the themes on the second unit of the textbook, which is about The Robber Barons. The main WebQuest task for the course LM-1030 has the following format (the outcome is boldfaced):

“You and your three classmates are interested in learning about the life of John D. Rockefeller (1837-1937), who was one of the most prominent philanthropists of American history. Paradoxically, he was known as a robber baron. Your task is to look for information on (1) his biographical details (birth, early years, family, adult life, and major events), (2) Standard Oil, (3) reasons why he is known as a robber baron, and (4) philanthropy and his final years. After this, your group has to explain the most relevant aspects of his life and explain why John D. Rockefeller is still considered a robber baron although he was a great philanthropist. Be ready to answer questions from the rest of the class.”

b. Setting the task: The group members need to know specifically what to look for. Individually, each person does research on ONE aspect and then share his or her findings with the other three members. Sample instructions are these:

Step 1: You need to work in groups of four classmates in order to look for the following information:

Student 1: Rockefeller’s biographical details

Student 2: Rockefeller and Standard Oil

Student 3: Rockefeller as a robber baron

Student 4: philanthropy and his final years

Step 2: As a group, prepare a short oral report to share your findings with the class.

Step 3: Explain the reasons why John D. Rockefeller is knows as a robber baron.

c. Process: In regard to this section, this explains how learners will carry out the WebQuest. It consists of giving clear instructions related to the time allotted, number of group members, the websites to be consulted, and the role of each student. If necessary, a group leader could be chosen.

It is important to explain that the previous information is an example of one WebQuest to be carried out by only one group with four students. In larger classes, the instructor may design more topics so the information is broadened depending on the number of learners. For example, the following section includes four additional topics in order to work with twenty students.

d. Resources: If the class was divided into five sub-groups, each one will investigate on one robber baron, which is the topic of the lesson and the reading textbook. So, the instructor has to assign reliable websites to each group to cover various topics. In this case, these are the five groups and their online resources (this includes twenty students):

Group 1: John D. Rockefeller (www.history.com)

Group 2: Andrew Carnegie (www.wikipedia.com)

Group 3: J. P. Morgan (www.britannica.com)

Group 4: Cornelius Vanderbilt (www.biography.com)

Group 5: Charles Yerkes (www.theamerican.co.uk)

It is worth noting that online resources must be trustworthy and academic. This is a time-consuming process as instructors have to select reliable websites for each topic.

e. Evaluation: This type of research-based activity has to include clear outcomes; this may be an oral report or a short written text, for example. If necessary, a set of rubrics may be used to evaluate students’ outcomes, especially if this is used as an evaluated assignment or quiz. The role of the instructor is to be a facilitator throughout the activity, for example, at the moment of encountering unknown words.

f. Conclusion of the WebQuest: Once all the five groups have presented, the instructor then makes a final comment to summarize, for instance, some of the similarities that those robber barons have. He or she may ask about possible problems while reading the articles online or the level of difficulty of topic-related words. This can also be followed by homework or reading exercises from the reading course textbook.

Procedure

The writer implemented three different survey questionnaires to assess students’ perception of various motivational and academic factors, being the most important the perception towards the type of group work activities they would like to carry out. This first instrument has eleven questions and was implemented on the first class (day 1). Seven weeks later, a second instrument was implemented to compare or expand on the results and opinions in relation to the first questionnaire.

There is a third instrument to collect students’ opinions regarding the types of activities, and how they have perceived the constant use of group work in every class since the first class. The instruments also intended to observe students’ perception towards the final group project. This was conducted one week before the final reading exam. The Appendixes contain the three instruments. They were prepared in Spanish since most students do not possess the level to write comments or complete ideas in English.

5. Data Collected

5.1 Results Gathered from Instrument A

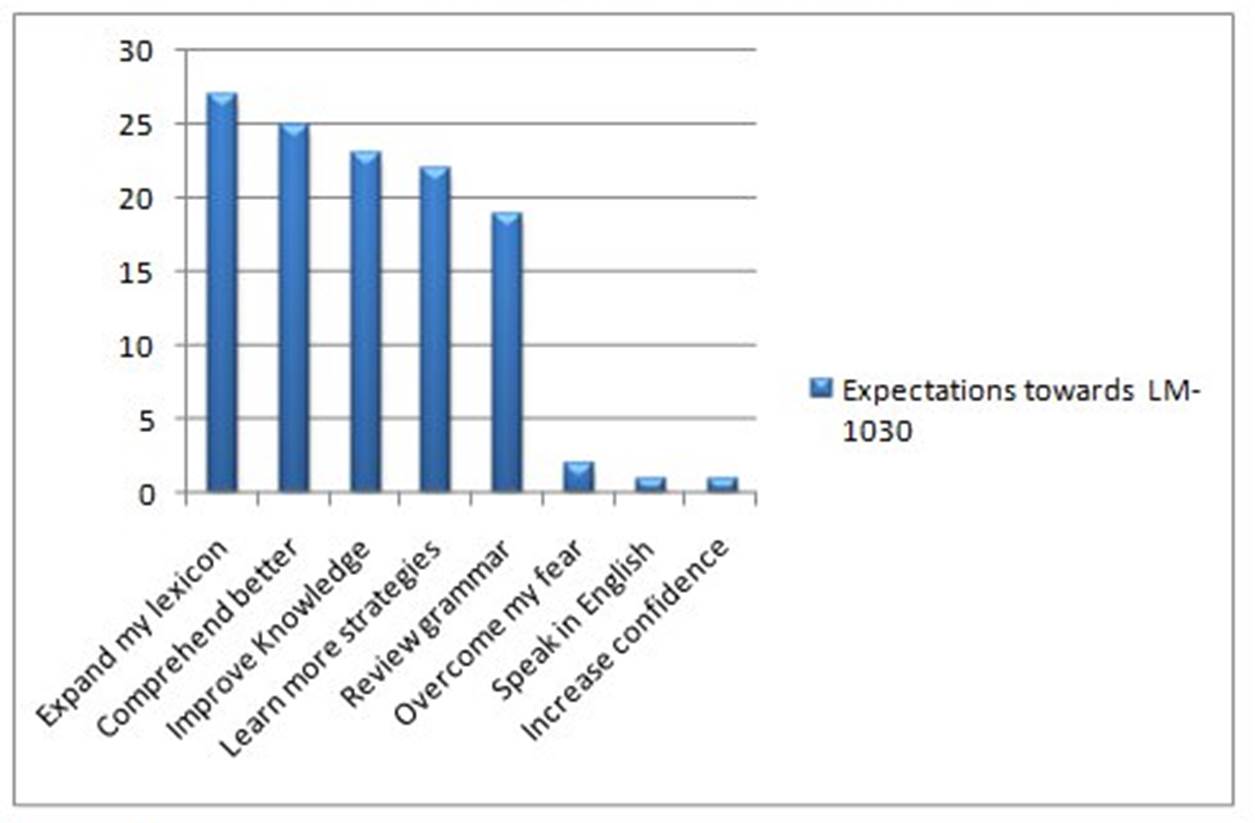

These are the data gathered with the first questionnaire (see Appendix A). Students range in age from 17 to 25. The 27 learners who filled out this instrument studied the following majors at the University of Costa Rica: Architecture, Accounting, Psychology, Political Science, Computer Engineering, Medicine, Social Work, Mass Communications, Chemical Engineering, Library and Information Science, Physical Therapy, Physics, Primary Education, Preschool Education, Nursing, History, Law, and Geography. In addition, a relevant aspect is that 10 students were taking first-year courses; 10 were taking second-year courses; 5 belonged to their fourth year of the majors, and only 2 took third year courses. The chart below summarizes the students’ expectations towards the course LM-1030 Reading Strategies I. Students had the possibility of marking more than one option if necessary.

The following question aimed at knowing whether or not students would take this reading course if it would not have been mandatory. In this case, 18 students said they would register it and only 9 that they would not. Among the ones who marked Yes, they expressed they would take it for three main reasons: being a slow reader, lacking reading skills to encounter academic articles for investigation projects, or being interested in learning languages. Some would not take it because this course is time consuming or difficult, especially if they focused on French courses in high school and had basic English instruction. Two people expressed they are not motivated.

Regarding question #6, 17 students indicated they had heard either positive or negative comments about the course, being social networks the primary sources of these comments. Among the comments, some people expressed they heard the course is boring, time consuming, or even pertinent if one lacks the necessary strategies to read; 4 students indicated it is relevant if one has to look for references while working on a graduation project.

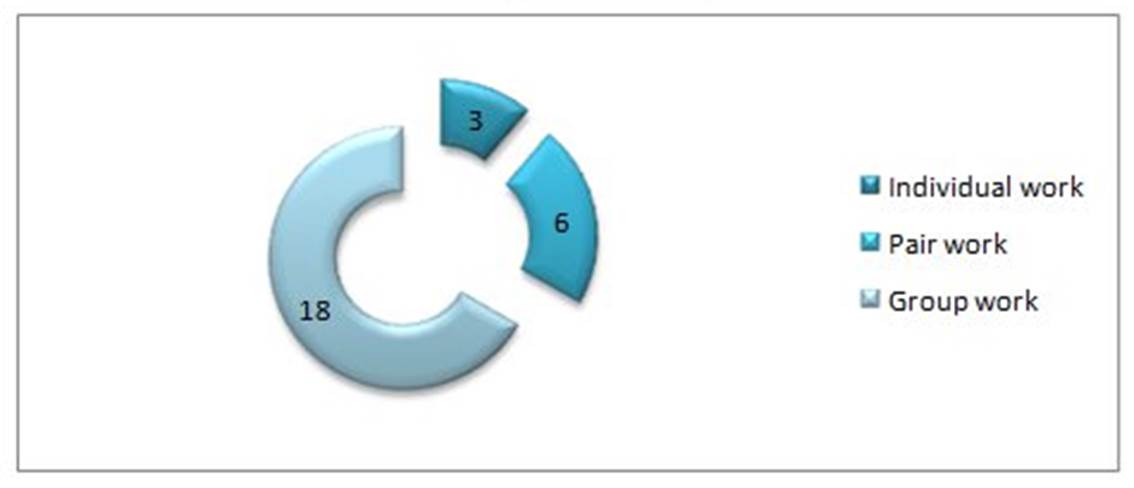

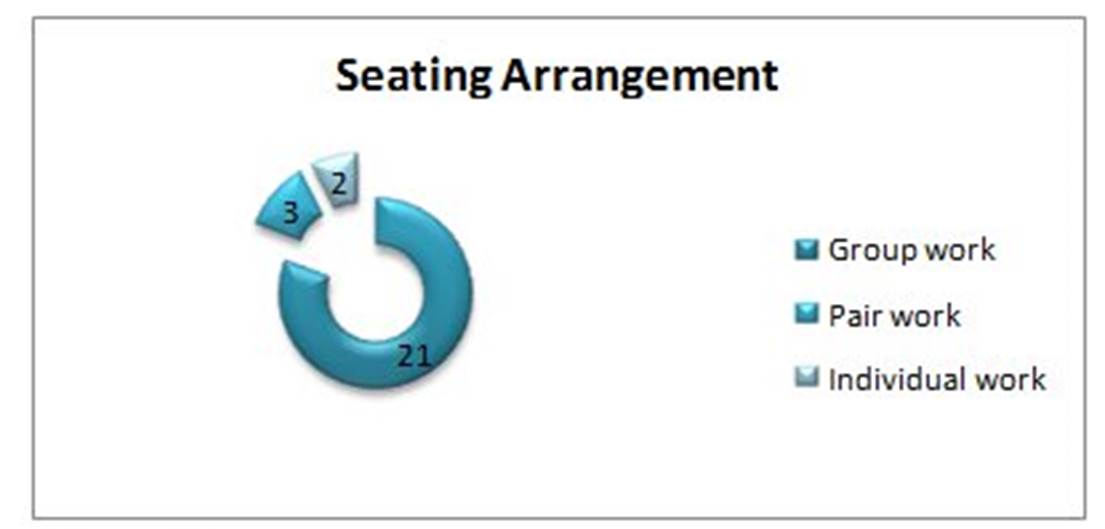

Question #7 intended to rank students’ perceptions towards their current level of motivation to take LM-1030 Reading Strategies I (during the first week of the semester). In this case, 15 marked 8 or above and 12 students marked 7 or below, being 1 the lowest level of motivation. Question #8 was included to assess if students would prefer to work individually, in pairs, or in small groups (3-5 members each). This is a pertinent aspect in this small-scale study. Figure 3 summarizes the results obtained:

They expressed they prefer to work in groups to compare one’s work with other classmates,’ lower the level of anxiety, cooperate with one’s peers, learn from other people’s technical vocabulary and knowledge on various areas of expertise, and finally, have a more appealing class environment. On the other hand, the next question was included to see students’ previous English instruction before taking this course. Just 10 students had taken English courses before in various contexts or institutions: English for Specific courses (ESP), INA, Centro Cultural Costarricense Norteamericano, Programa Cursos de Conversación Inglesa (UCR), Fundatec, Universidad Latina, and Boston Academy; 17 lacked formal instruction in English.

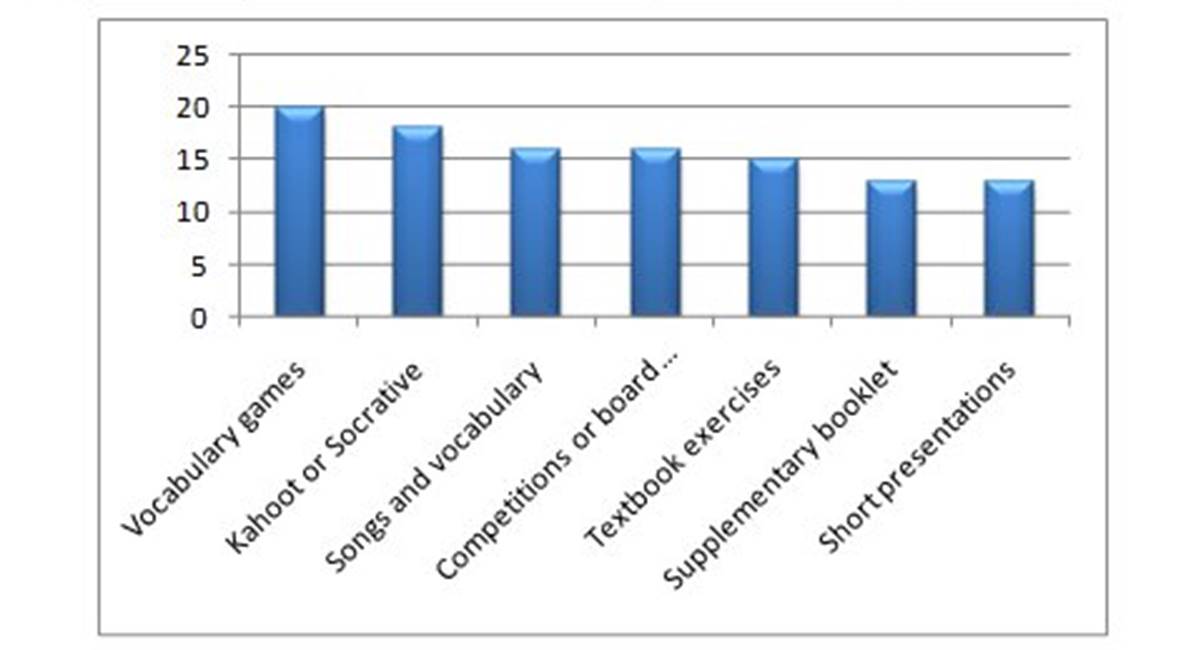

Although there is a significant number of group activities one may prepare for a reading strategies course, Question #9 aimed at assessing the type of class activity to be carried out in groups, preferably with three or four members. The figure below highlights the top activities based on students’ choices:

Finally, in regard to what these students perceive as their current level of reading comprehension in English, 22 ranked it as 7 or below, and only 5 expressed it should be 8 or even above.

5.2 Results Gathered from Instrument B

The second questionnaire, which was administered in the middle of the semester with 26 students, was aimed at examining the students’ perception towards group work while carrying out various tasks throughout the first part of the course. The first question examines the impact of the presentations on various grammatical structures, which were carried out in groups of 3-4 members. Each group had to explain, compare and contrast two verb tenses, implement two grammar exercises, and carry out one interactive activity. In this regard, 15 students indicated that the benefit of this group presentation was Sufficient; 3 students marked A lot; 8 people chose the third option: Little, and no one marked the last option (None).

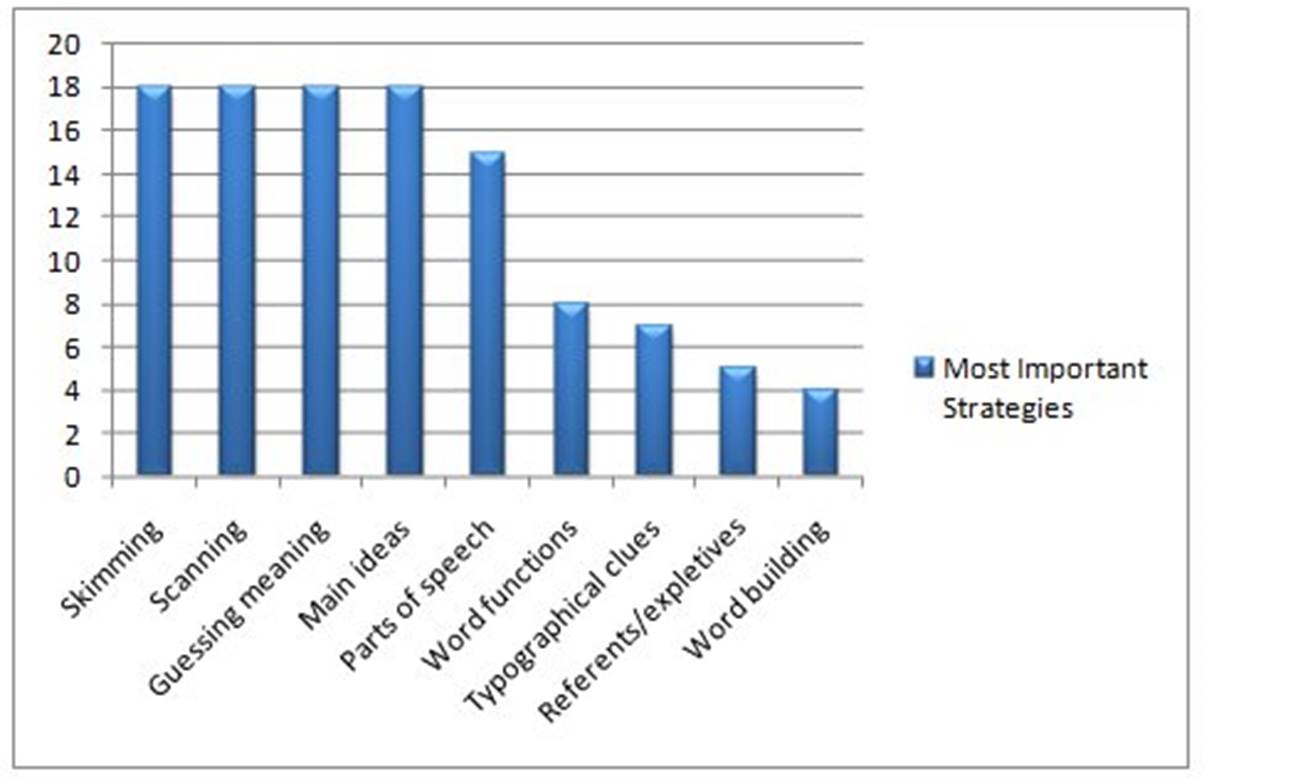

For the purpose of this study, the second question is important as it examines the relevance of the direct instruction of nine reading strategies, which were covered and practiced up to this moment. The table below summarizes the information gathered:

Based on the list above, students were also asked to indicate which strategies seemed to have the highest level of difficulty. The following list summarizes the number of points obtained in each topic: referents/expletives (8), word functions (7), parts of speech (4), main ideas (4), typographical clues (3), guessing meaning in context (2), and word building (2). In relation to these two questions, students had to point out those elements that cause more trouble at the moment of reading a given text. Thus, 20 students marked the option regarding the level of difficulty of words; 12 students chose the complexity of grammar structures included in the text; 8 people referred to the length of the text, and only 1 person marked the topic of the reading text as a troublesome aspect.

Question #5 was aimed at assessing if students’ level of motivation has changed up to this moment, being this the case of the seventh week of classes. So, 8 students expressed that their motivation increased; 15 people said that it has remained the same from week 1, and only 3 said that it decreased. The following question was included in order to see the general level of difficulty of all the content covered in this course; thus, 21 students expressed that the level is intermediate, and is correlates with the exact level of the course based on the Course Syllabus. Also, 2 students said that the level of all the topics is high and only 3 said the level is low.

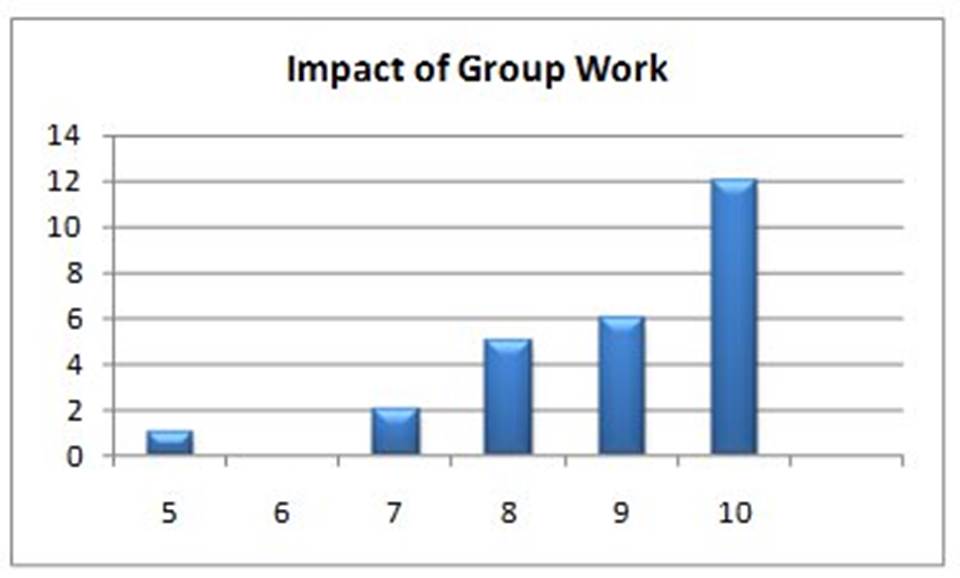

The purpose of asking question #7 is to gather this LM-1030 group’s perception of working in groups constantly during the first part of the course; the idea was for them to rank from 1 to10 the effectiveness of group work, being 10 the highest point. The figure below shows the results. It is worth noting that no one marked the options 1-4, so they do not appear in this chart.

The following question was prepared to make students list those strengths they noticed while carrying out different types of activities in groups. This list summarizes all the key ideas and the number of instances for each category: cooperation (13), negotiation of content (11), better comprehension of the topic (6), team group (6), problem-solution (4), tolerance (4), leadership (2), and less anxiety (2). Finally, and in relation to this, the last question was aimed at knowing whether or not students want to continue working in groups. The following chart shows the results:

5.3 Results Gathered from Instrument C

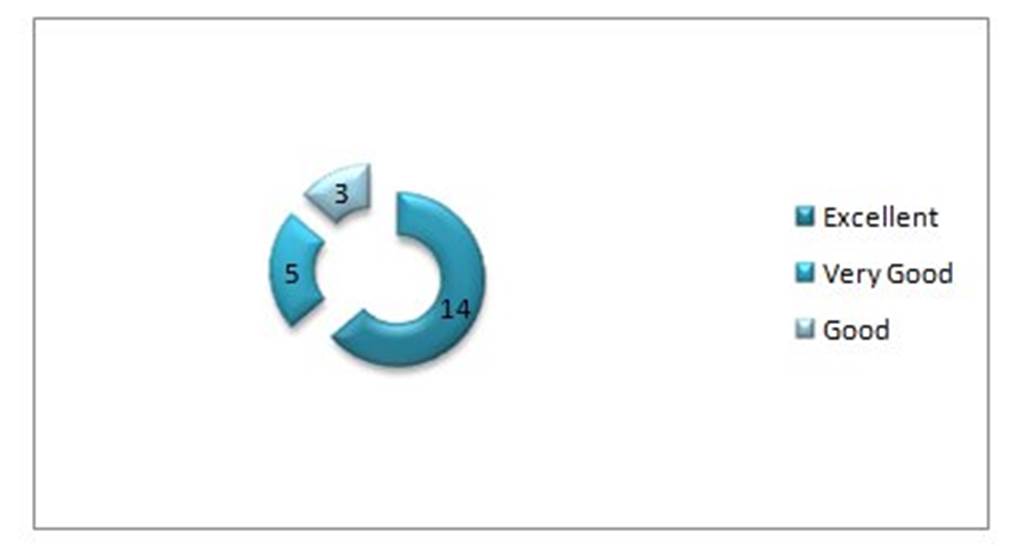

This final instrument was administered one week before the final test. Since attendance was a constraint, in this case only 22 students answered it in two separate lessons. The first questions attempted to assess students’ level of satisfaction throughout the process of preparing the final project. In this case, 16 students said the process was Excellent; 5 marked Very Good, and only 1 chose Good. The last two options were not chosen.

In the final reading project, students present a reading lesson based on a series of pre, while, and post reading tasks and exercises. They do so based on two reading strategies seen before. The topic of each project deals with the majors or areas of specialization of each sub-group. So, the second question intended to find out students’ interest in all the projects; 14 students indicated that the projects were Very Interesting and 8 marked the second option; Interesting. Once again, the last two options were not chosen. Question #3 tried to determine how much these students have learned at the end of all the project presentations. From the four options given, the first option (A lot) tied with the second one (Sufficient), and the last two were not marked.

Preparing the final project is part of a long process that lasts over a month. Creativity is a must as students design all the interactive tasks and exercises based on a reading text of their choice. Thus, question #4 attempted to assess students’ perception in regard to group work, which increased during the second part of the semester. It is important to mention that Fig. 8 does not include the last two options (Fair or Bad) as they were not chosen by students. So, the first three are represented as follows:

Question #5 was an open item as students had the possibility of indicating strengths and weaknesses of working in groups to prepare the final project during the second part of the course. The table below summarizes some of the answers:

Table 6 Group Work and Student’ Opinions.

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

| 1.Team work (5) and better flow of ideas (2) | 1. Some classmates are disorganized |

| 2.Collaborative work and trust (3) | 2. Availability outside the classrom |

| 3. Leadership and organization (2) | 3. Tolerance is not easy |

| 4. Professors guidance (e-mails) | 4. Grammar mistakes |

| 5. Learning from others (2) | 5. Lack of time (6) |

| 6. The process was easy (3) | 6. Technical problems during the presentation |

| 7.Easy online communication (Wiki) | - |

Source: Own work.

Question #6 was aimed at assessing if students’ level of motivation at the end of the reading strategies course increased, decreased, or remained the same. In relation to this, 15 students indicated it increased; 7 expressed it remained the same, and no one chose the third option (Decreased). Finally, the last question tried to observe the students’ improvement in their reading comprehension after studying all the strategies and working on the reading exercises. As a result, 18 students expressed that their comprehension of reading texts improved; 2 indicated that it remained at the same level, and 1 student indicated it did not improve. Also, one student did not answer this question.

5.4 Discussion of the Results

Based on Instrument A, this heterogeneous group (including students from 18 different majors at UCR) has received general English training and was highly interested in expanding the productive vocabulary and understanding various texts by using strategies; however, students still think this course had a strong grammatical component. Based on the writer’s observation in class, students liked the course materials, and this contrasts with the negative comments some have read from other students on social networks. Also, the findings show that students are aware of the importance of becoming better and more fluent readers, especially while encountering academic publications. Some students know they lack the basic reading tools to read better. Interestingly, 72% of this group expressed that working in groups is preferable to working individually or in pairs in order to carry out varied tasks, especially competitions.

In relation to the second instrument, 69% of the class indicated that the presentation of grammatical structures was beneficial to review and practice grammatical structures. Based on the class observation, they carefully carried out the grammar exercises and interactive activities and asked follow-up questions. As a consequence, the instructor provided some online resources to expand on this practice at home. In addition, the computer lab was also used four times during the semester; also, two students contributed with additional web pages. In terms of reading strategies, they indicated that skimming, scanning, guessing meaning in context, identifying main ideas, and determining parts of speech were the most useful strategies. The most difficult and challenging topics according to this instrument were word function and parts of speech, but during class time, students said that parts of speech was even more useful and practical, especially at the moment of consulting a monolingual dictionary.

In relation to group work, learners pointed out that there is an advantage and for those with a low level of reading comprehension, anxiety is reduced. Finally, the results of the third questionnaire indicate that students had a positive perception towards the process of preparing their reading project. They valued their professor’s feedback throughout the process; this includes the preliminary presentation one week before the due date. All 22 students had also a positive perception about the pertinence of this project. For them, it was very interesting to learn from concepts related to different majors and areas of expertise and also put into practice many reading strategies studied before. However, group work had advantages and disadvantages.

To reduce communication problems, a short period of time was dedicated to plan the different sections of this group project. Most importantly, 81% said that their comprehension of reading texts improved at the end of this course. Even though many students pointed out that the level of the course is intermediate, some expressed that the level of difficulty of the reading strategies and texts was higher. In this case, the implementation of a virtual classroom is useful. It was available throughout the semester and updated each week. Figure 8 illustrates one section of the virtual setting, which is empowered by METICS at the University of Costa Rica. All students have access to this resource.

6 Recommendations and Conclusions

Based on the results obtained after administering the three instruments, some suggestions regarding group work in this particular reading course include the following:

a. integrate learners into well-structured group activities to foster cooperative learning; thus, beginners may benefit from the knowledge of advanced students;

b. assign a specific role for each member so that the class will take advantage of time and resources (computer labs or mobile devices);

c. WebQuests are an excellent option as this is a very structured task;

d. beginners or low-intermediate learners should work together as novice learners need “a positive, supportive atmosphere,” and the implementation of group work in every class helps to achieve this (Hadfield, cited in Williams and Burden, 1997, p. 195);

e. in such a reading course, where there is a wide variety of difficult texts and topics, those students who pursue a given major or specialized level of expertise should contribute with relevant comments or explanations while using the reading textbook;

f. in terms of seating arrangement, it is recommended for students to interact with peers they have never worked with before;

g. students like to be competitive, but this does not necessarily affect cooperative groups;

h. instructors should vary the topics of reading texts in exams and choose those that tend to approximate all the group’s background knowledge;

i. the instructor should have a virtual classroom as a valuable online resource with extra practice, multimedia material, and summaries;

j. instructors should have a review of grammar structures such as verb tenses as they help students refresh basic aspects they will certainly encountered in reading texts; and finally,

k. instructors should consider if the grammatical component of the course should be reinforced in terms of additional exercises based on short reading texts.

To sum up, perhaps, one of the most notorious challenges of having a heterogeneous group is to choose various reading tasks. Videos, for instance, are always appealing for a young audience, but they should include English subtitles. Although a reading course is not very interactive in nature due to the load of content or exercises, implementing group work definitely changes the class atmosphere as long as tasks are varied. By combining group work with appealing reading tasks, students will benefit from the strengths of both aspects regardless of their reading level.