Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the air ways characterized by bronchospasm, an inflammation of the smooth muscles in the bronchi. The main symptoms of asthma are difficulty breathing, wheezing, and chronic dry cough (Kline-Krammes, Patel & Robinson, 2013). Common triggers for asthma exacerbations include dust mites, animal dander, cockroaches, pollen, mold, and other allergens; air pollutants and tobacco smoke; viral respiratory infections; aspirin and other drugs; stress; and sometimes exercise (Murata & Ling, 2012). Additional risk factors include certain foods and area of residence, especially hot and humid areas (Soto-Martínez & Soto-Quirós, 2004).

Severe asthma can lead to respiratory failure if not treated quickly (Murata & Ling, 2012). The cost of treating asthma is high, especially because it can lead to one or more ER visits per year. It is the leading cause of missed school days and it can affect a child's sleep and academics (Kline-Krammes et al., 2013). Asthma can be socially and emotionally harmful for a child due to reduced participation in recess, sports, vacations, and other activities (Gutiérrez & Chavarría, 2000; Williams et al., 2010).

Unfortunately, there is no cure for asthma. Instead, treatment should focus on controlling environmental triggers, maintaining physical activity, and teaching management skills to the patient, parents, and other caretakers (Korta Murua & López-Silvarrey Varela, 2011). When an asthma attack does occur, immediate treatment with bronchodilators is necessary. The principal medications for asthma are beta-agonists, systemic corticosteroids, and ipratropium bromide (Kline-Krammes et al., 2013). The recommended immediate therapy for acute asthma attacks is short-acting beta-agonist (SABA) drugs, which rapidly relax bronchial smooth muscles. The most common SABA is salbutamol, administered in a metered-dose inhaler (Murata & Ling, 2012). Barriers to asthma management include low medication compliance, poverty, transportation difficulties, inconvenient clinic hours, limited communication between schools and families, and the lack of written asthma action plans (Toole, 2013).

Based on the most recent International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (conducted 2000 2003), Costa Rica consistently had one of the highest rates of childhood asthma in the world (Lai et al., 2009). The prevalence of asthma among Costa Rican children increased from 23,4% in 1989 to 33,2% in 2002. This escalation might be explained by improvements in the clinical diagnosis of asthma; environmental changes, such as increased air pollution; and lifestyle changes, such as decreased nutrition and physical activity (Soto-Martínez & Soto-Quirós, 2004; Cooper, Rodriguez, Cruz & Barreto, 2009). According to a study among asthma patients in the Hospital Nacional de Niños in San José, many parents waited too long to seek medical treatment, which led to costly emergency services. A high percentage of patients lacked regular medical treatment despite national health coverage and improvements in asthma medications. These results indicate a need for improved preventative health in Costa Rica (Gutiérrez & Chavarría, 2000).

Many studies have indicated a lack of asthma knowl-edge among teachers worldwide (Getch & Neuharth-Pritchett, 2009; Bruzzese et al., 2010; Rhee, Wyatt & Wenzel, 2006; Angulo, 2013). According to a study in Spain, only 35, 9% of teachers had received some type of information about the first steps to follow during a student's asthma attack (Rodríguez Fernández-Oliva, Torres Álvarez de Arcaya & Aguirre-Jaime, 2010). The best strategy for asthma management includes patient education, a written asthma action plan, early recognition of symptoms, and rapid treatment of asthma exacerbations (Kline-Krammes et al., 2013). The cooperation of an asth matic child's teachers is essential for all of these efforts. Similarly, researchers in Chile suggest that educating community members-including teachers-is essential for helping parents detect asthma in their children, seek specialized assistance, and avoid unnecessary treatments for their children (Mallol et al., 2000).

Costa Rican schools generally do not have a school nurse, which is why the teachers play such an important role in the management of students' asthma and other medical conditions. It is possible that many teachers might not recognize the symptoms of an asthma attack. This could have serious consequences for the children; a severe asthma attack may require intubation and can even be fatal. The teachers cannot be blamed, because this deficiency exists at the institutional rather than the individual level. There are few studies about teachers' asthma knowledge in Costa Rica specifically. Most asthma studies in Latin America have been conducted in urban areas, where risk factors include extreme so cial inequalities and lack of access to basic infrastructure (Cooper et al., 2009), but these risk factors may apply to rural areas as well. I loosely based this study's questionnaire on a previous asthma knowledge study that was conducted in a San José primary school (Angulo, 2013). To expand on this subject, I decided to research teachers' asthma knowledge in rural Costa Rica.

By means of an asthma survey, I aimed to: a) measure the proportion of teachers that have witnessed an asthma attack in the classroom and investigate the actions that they took; b) determine teachers' awareness about asthma attack prevention, triggers, symptoms, and medications; and c) gauge teachers' interest in asthma training. The goal of this study is to contribute to an understanding of the current level of asthma knowledge in rural Costa Rican schools.

Methods and materials

Study Area, Sample Size, and Participants: Venecia and Aguas Zarcas are located in the canton of San Carlos, in the north-central province of Alajuela, Costa Rica. Their approximate populations are 6 000 and 13 000, respectively. These rural towns have a very warm and rainy climate. The mean annual temperature ranges from 17 to 24°C, with a mean annual rainfall of 3768 mm over an average of 226 days per year (Solano & Villalobos, 1996). Six public schools participated in this study: one secondary school and four primary schools in Venecia, and one secondary school in Aguas Zarcas.

The overall participation rate was 88, 9%, providing a sample size of 185 teachers. Of these participants, 23% worked in a primary school (preschool through sixth grade) and 77% worked in a secondary school (seventh through twelfth grade); 32% were men and 68% were women. Their ages ranged from less than 25 years to 59 years, but 67% were in their thirties or forties. Their teaching experience ranged from 1 to 20 or more years, but 62% had worked for 8 to 19 years. Some teachers held a high school, bachelor's, or master's degree, but 64% held a licenciatura degree (one to two years of technical training beyond a bachelor's degree). About 11% of the teachers were asthmatic, and 23% lived with an asthmatic person.

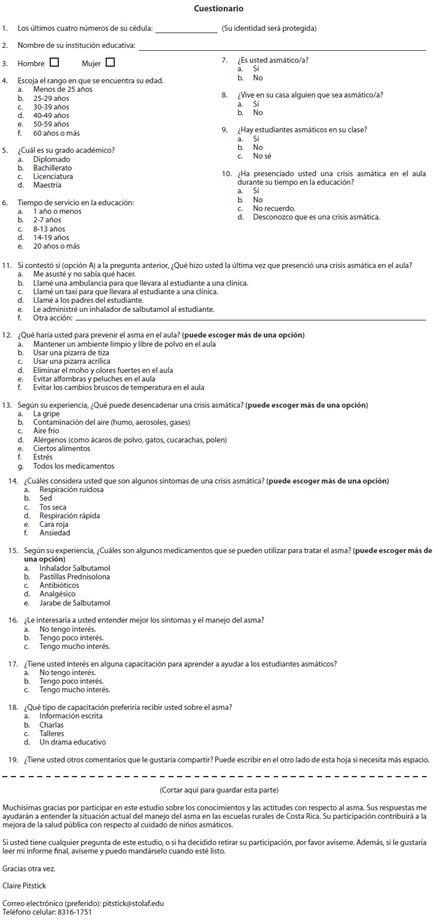

Methodology: The asthma questionnaire (Appendix A) consisted of 19 questions regarding demographics, personal experience with asthma, classroom experience with asthma, asthma knowledge, interest in an asthma training program, and comments. For the four knowledge questions (regarding asthma attack prevention, triggers, symptoms, and medications), more than one answer choice was allowed, and each question included one or two incorrect options. During March and April 2014, I distributed the questionnaires to the teachers during the school day, aiming to sample all teachers at the six schools. The participants also signed an informed consent form. Collection of the questionnaires and forms was performed later in the day or week, depending on the teachers' availability. I used a code system to sepa rate the participants' names from their questionnaires. This study was approved by the ACM Ethics Panel and followed a specific plan for the protection of human re search subjects.

Using the knowledge questions about asthma attack prevention, triggers, symptoms, and medications, I summed the correctly identified items and subtracted the incorrectly identified items to generate a Knowledge Score (KScore), which could range from -6 to +18. The levels of interest in asthma training (none, low, or high) were translated into a Training Score (TScore) of 0, 1, or 2, respectively.

Differences in mean KScores and TScores among teachers' various characteristics or experiences were estimated by parametric, one-way ANOVA. A posteriori comparisons between means were carried out with Least Significant Difference (LSD) and Scheffe tests. Some comparisons were accompanied by Chi-Squared tests. Dependency of "training interest" levels with "asth matic student awareness" levels and "witnessed asthma attack" levels were estimated with contingency tables. Dependency of "asthmatic student awareness" levels between primary and secondary school teachers was also estimated with a contingency table. The questionnaire answers were entered and analyzed in Microsoft Excel, and statistical analysis was completed with Statgraphics Centurion XVI, Version 16.0 (Statpoint Technologies, Inc.). Statistical procedures followed Sokal and Rohlf (1995).

Results

Among the teachers, 51% were aware of asthmatic students in their class, and 37% were not sure if they had asthmatic students or not. Among the primary school teachers, 67% reported that they had asthmatic students in their class, 19% reported no, and 14% did not know. These proportions contrasted with the secondary school teachers, of whom 46% reported asthmatic students, 10% reported no, and 44% did not know (X2=13,05; df2; p=0,002).

Furthermore, 19% (35 teachers) recalled witnessing an asthma attack in the classroom. Within this group, 80% called the student's parents or an ambulance, and 29% either helped or let the student use an inhaler, with some overlap between these responses. The most commonly identified strategies to prevent asthma attacks in the classroom were keeping the room clean (92%) and using a whiteboard instead of a chalkboard (83%). When asked about possible triggers of an asthma attack, teachers most commonly chose air pollution (89%) and allergens (87%). The majority of the teachers were able to identify the three main symptoms of an asthma attack: wheez-ing (73%), dry cough (52%), and rapid breathing (80%). For asthma medications, 99% of the teachers correctly identified the salbutamol inhaler, and the second most common choice was salbutamol syrup (52%), which is prescribed for small children. When asked about possible training to learn how to help asthmatic students, 85% of teachers expressed a high level of interest. The preferred types of training were a lecture or workshop, but some teachers were interested in written information or an educational skit.

With a possible maximum of 18, the participants' KScores ranged from 3 to 17. The mean KScore was 10, 26 with a standard deviation of 2,85. Statistically significant relationships were found within the categories of "asthmatic family member" and "interest in asthma training" (Table 1).

The TScore ranged from 0 to 2 with a mean of 1,84 and a standard deviation of 0,41. Teachers who knew they had asthmatic students were more interested in asthma training than the other teachers (X2=9,14; df 4; p=0,058). Teachers who reported that they could not recognize an asthma attack had the highest mean TScore (2,00), followed by those that had witnessed an asthma attack (1,86), then those who had not (1,85), and finally those who could not remember (1,43) (Table 2). Thus, the teachers with the least interest in training were those that could not remember whether they had witnessed an asthma attack (X2=13,72; df 6; p=0,033).

Discussion

Areas for Improvement in Asthma Knowledge: It is alarming that so many teachers did not know whether they had asthmatic students in their class or not. This lack of awareness was higher for the secondary school teach ers, who generally have more students than the primary school teachers, thus making it more difficult to keep track of their students' medical conditions. Several teachers wrote in the comments that it should be the institutions' responsibility to provide each teacher with a list of the asthmatic students. The need for better communication among students, parents, teachers, and administra-tors has been suggested in previous research ( Rodríguez et al., 2010; López-Silvarrey Varela, 2011). Most teachers who witnessed an asthma attack did not help administer the salbutamol inhaler to the student. Although calling an ambulance or the student's parents is important, this should not be the first action. The medication must be administered as quickly as possible, because every min ute counts during a severe asthma attack (Dr. Anabelle Alfaro, Emergency Medicine Specialist, 2014).

Overall, the results of the four knowledge questions paralleled those from a San José elementary school (Angulo, 2013). The teachers were generally aware of the main strategies to prevent asthma attacks in the class-room, with the exception of avoiding sharp temperature changes. This is difficult in Costa Rican schools since most classrooms are open to the air and the weather can change rapidly. Although asthma attack triggers differ among individuals, teachers should be aware of respiratory viruses, cold air, certain foods, some medications, and stress in addition to the commonly identified air pollution and allergens. Most teachers recognized wheezing and rapid breathing as symptoms of an asthma attack, but they need to be more attentive to dry coughing and anxiety as well. It is excellent that almost all of the teachers recognized the salbutamol inhaler as an asthma medication, but they might not know how to use it correctly.

Fortunately, there was a high interest in asthma training, especially a lecture or workshop, which is consistent with studies in San José and Spain (Rodríguez et al., 2010; Angulo, 2013). An educational asthma intervention program for teachers should be individualized to the type of teacher and should emphasize recognition of symptoms and inhaler administration (Rodríguez et al., 2010). The Caja Costarricense de Seguro Social (The Costa Rican Social Security Administration) has already published a detailed guide for asthma exacerbations in children (Román Ulloa & Sáenz Campos, 2010). This guide can be used to design a training program, with the help of a health professional.

There was no clear relationship between the teachers' KScore and their age, experience, or education. Also, the trend that women had a higher KScore than men is consistent with a study in Istanbul, where asthma knowl edge was greater for women, but was not related to age, education level, or length of tenure (Ones, Akcay, Tamay, Guler & Dogru, 2006). This indicates that teachers are not learning about asthma as a result of their career it-self. However, teachers who lived with an asthmatic per-son had a higher KScore than those who did not, likely because caring for an asthmatic family member would increase familiarity with asthma attack prevention, triggers, symptoms, and medications. The influence of per sonal experience also increased the KScore for asthmatic teachers in comparison to non-asthmatic teachers, but the relationship was not as strong. The importance of personal experience is evident in previous studies (Getch & Neuharth-Pritchett, 2009; Rodríguez et al., 2010).

The teachers with higher KScores were highly interested in training, which is excellent, but the teachers with lower KScores were more likely to express little or no interest in training. This could lead to very negative consequences for their asthmatic students. The average TScore was higher for teachers who knew they had asthmatic students, as well as for the teachers who had either witnessed or could not recognize an asthma attack. It would be even better if the other groups expressed higher interest as well. A proactive approach is always better than a reactive approach, especially in the case of a life-threatening disease (Bruzzese et al., 2010).

Recommendations: It is important to consider the limitations of this study. Primarily, my questionnaire did not undergo a validation procedure, which hinders comparisons to other studies. Also, asking for numerical values, rather than ranges, for teachers' age and years of experience would have allowed more precise statistical tests, such as regression. To gain insight into teachers' attitudes about asthma, I should have included a question about the perceived danger of an asthma attack. Lastly, since I did not always monitor the participants, they may have shared answers or used online resources to answer the knowledge questions.

Training for teachers should focus on the prevention of asthma attacks in the classroom, recognition of symptoms, and the correct administration of a salbutamol inhaler while waiting for the ambulance or parents to arrive. A local pediatrician, asthma specialist, or pub lic health official could provide training. To ensure that teachers are aware of asthmatic students in their classes, administrators should use the students' medical files to create and distribute a list of asthmatic students to each teacher. It is also advisable to include an inhaler in each classroom's first aid kit.

It would be beneficial to research current laws world-wide regarding teachers' abilities to care for students' medical needs, as well as teachers' comfort levels in administering medications like inhalers. Furthermore, interviews with parents and pediatricians of asthmatic children would reveal their concerns about asthma man agement at home and at school. When asthma training is provided to teachers, a follow-up study will be essential. If the results are satisfactory, then the training program should be extended to other schools in Costa Rica and Latin America.

uBio

uBio