Introduction

Teaching English as foreign language in Chile has been one of the main concerns for our educational system. Over the years, the Ministry of Education has suggested different proposals and strategies; the Eng- lish curriculum guidelines have been modified lately due to the importance of a contextualized language teaching practice. Within these curriculum changes, the new teaching strategies have focused on a more meaningful, communicative and effective way of learning a foreign language. The Ministry of Educa- tion has also suggested aligning lesson planning with a more integral teaching practice with the help of other subjects in an interdisciplinary way.

New strategies for learning a new language have been of great importance, as traditional methods of language teaching have not been enough to provide our students with the best tools to effectively communicate with each other in a society laden with tech- nological devices and digital resources. This constant pursuit of the most suitable teaching strategy within our teaching context led us to decide to use differ - ent ways of offering students the opportunity to work with English in a non-traditional way known as a drama-based strategy. Even though it is not a revolutionary discovery, several pedagogy experts find it is a useful strategy and support its use in the classroom. Baruch (2006) stated that the effectiveness of teach- ing can be enhanced and enriched by applying theatrical role-playing, sometimes in the shape of putting on metaphorical masks. This study aims to examine the implementation of scripted role-plays based on drama strategies to improve seventh grade students’ willingness to participate in speaking activities in English.

Drama as a strategy for teaching English as a foreign language

Teachers have to manage different strategies and approaches when of preparing and applying their lessons (Ku ś nierek, 2015). In this particular case, re- garding the wide variety of strategies and methods to teach and foster the speaking interaction, it is im- portant to point out that drama is not only a cultural aspect of our society that brings joy and recreation time, but also, as Trachtulcová (2007) claimed, drama is doing, drama is being. It implies taking part of a real interaction and gives the opportunity to the performer to play the role of someone else and put in his/her shoes. Wessels, (1987) added that drama is something that we all engage in daily when faced with difficult situations along our lives and in differ - ent contexts.

Despite widespread interest in using drama for more contextually situated, engaging, and communica- tive language use in the classroom, according to Kim (2013), ironically, drama does not seem to be widely implemented in language classrooms, maybe out of fear of bringing into the classroom something that teachers do not feel knowledgeable enough to implement. On the other hand, use of drama is not only for recreational purposes or for our personal development and growth; nor is it an isolated method to enhance interaction in the classrooms. Belliveau & Kim (2013) state that a number of scholars in the field recognize the pedagogical contributions of drama. Some of these benefits closely relate to the fact that drama encourages adaptability, fluency, and communicative competences (Zhang, 2010). Kim (2013) emphasized that drama puts language into context and that giving learners an experience of success in real-life situations should arm them with the confi - dence to tackle the world outside the classroom.

Aliakbari (2010) suggested that drama pedagogy might be one of the optimal ways to foster and real- ize communicative language teaching. Belliveau & Kim (2013) explained that growth in fluency in the target language occurs as learners experience the complex nature of authentic communicative aspects of language (i.e., hesitation, intonation, repetitions, and incomplete sentences) even during product-ori- ented, scripted theatrical activities. They also engage in rehearsals and performance, which calls for collaboration, negotiation, and meaning exchanges at personal and public levels among participants.

For students to achieve speaking mastery, it is necessary to provide them with the appropriate environment to feel confident enough to participate of the interactions planned for each English lesson in order to communicate and transmit the exact message they intend to. In any written or oral interaction between two or more agents, the main purpose is to communicate and express their ideas and thoughts (Maziha, Suryani & Melor, 2010). Crystal (2008) defined communication as the transmission and reception of information between a source and a receiver using a signaling system: in linguistic contexts, source and receiver are interpreted in human terms, the system involved is a language, and the notion of response to (or acknowledgement of) the message becomes of crucial importance. In theory, communication is said to have taken place if the information received is the same as that sent.

Role - playing

According to Westrup & Planander (2013), role-play can be defined and implemented in several ways. Qing (2011, p. 37) claimed, “role-play is defined as the projection in real life situations with social activi- ties”. Role-playing allows learners to be in different characters’ shoes, which helps them to develop their language skills as well as their social ones. Therefore, role-play, according to Richards and Rodgers (2001, as cited in Aliakbari, 2010), refers to the part where learners and teachers are expected to play in carry- ing out learning tasks as well as the social and in- terpersonal relationship between the participants. Erturk (2015) also suggests that role-play is suited for teaching soft (personal and social) skills to students and professionals. According to Porter- Ladousse (1987), there exist many role-play activities, ranging from highly-controlled, guided conversations at one end of the scale to improvised drama activities at the other; from simple rehearsed dialogue performance to highly complex simulated scenarios. Porter- La- dousse (1987) also points out that role-play may dif- fer in complexity, that is, some performances may be very short and simple, whereas some utterances may be very structured.

The empirical review for this action research supports what has been carried out in the field in terms of using role-plays and drama as strategies to teach a foreign language. Furthermore, considerable number of studies have been developed in the field of role-play. Aliakbari (2010) studied the interpretation of role- play by two different groups. In his study, one group simply carried out the instructions in a mechanical fashion. Another group reconstructed the task in ac- cordance with their own goals. They showed that the kind of talk produced by two groups differed greatly, with far more metatalk evident in the second. On the other hand, Najizade (1996) concluded that role-play was considerably effective as an activity for bringing real language situations into classroom, improving the subjects’ foreign language structure acquisition.

Another study carried out by Liu and Ding (2009) regarding role-play in English language teaching asserts that teachers “used the role-play technique to see how the students performed in groups when they were given a familiar situation to role-play in. They also observed their language potency and how the errors can be corrected as well as how to give feedback to the learners for further improvement” (p. 223). Priscilla Islam & Tazria (2012) conducted a study entitled “Effectiveness of role-play in enhancing the speaking skills of the learners in a large classroom”. Roughly 120 students from Stamford University in Bangladesh were involved in this research process in speaking classes. Results show learners improved in speaking skills through roleplay and the positive attitudes of teachers helped them to further develop their speaking skills.

The fourth empirical research chosen was conducted by Trachtulcová (2007). Her study, titled “Effective Learning of English through drama”, was conducted at a primary school. It proved that using some ac- tivities from the area of dramatic education enrich the process of teaching. A study by Heyward (2010) uses dramatic role-play in teacher education to make pre-service teachers’ learning immediate, real and emotional. The author argues that the use of role- play offers a unique opportunity to both engage students emotionally in the fictional world of drama and maintain a safe learning environment.

Student class participation

Learning is a process mostly determined by the teachers’ strategies regarding student participation, self-awareness, and behavior (Sirisrimangkorn & Su- wanthep, 2013). Maziha, Suryani & Melor (2010) described four types of student behavior in the class- room: full integration, participation in the circum- stances, marginal interaction, and silence observation.

Full integration

In full integration, students actively engage in class discussion or activities; they know what they want to say and what they should not say. Their participation in class is usually spontaneous, appropriate, and oc- curs naturally (Abidin, 2007).

Participation in the circumstances

Participation in the circumstances occurs when stu- dents are influenced by factors such as socio-cultural, cognitive, affective, and linguistic or environmental, and these often lead to student participation and in- teraction with other students and instructors. In ad- dition, students will think carefully about what is the appropriate time for them to speak out their opinion with a preference for appropriate behavior during the lesson. They also show their reaction carefully to each discussion topic they think is more difficult for them (Abidin, 2007).

Marginal participation

In marginal interaction, students act more as listeners and less as speakers. Unlike the students who are actively participating in the classroom, this category of students prefers to listen and take notes than to be involved in classroom discussion (Lee, 2005).

Silent observation

Silent observation, on the other hand, is characterized by students’ withdrawal from oral classroom participation. These students seem to accept whatever is discussed in class. To help them digest and confirm what has been communicated in class, these students use various strategies, such as tape-recording, note- taking, or small group discussion after class. In silent observation, students tend to avoid oral participation in the classroom (Abidin, 2007; Maziha, Suryani & Melor, 2010).

Individual consciousness emerges due to and through communicative interaction with others. The importance of social interactivity is that, through it, the instruments and signs of culture are internalized . Cultural mediation is fundamental to all human ac- tivity, whether directed towards the physical world or the social world. It explains why interaction with others (and the interaction of the subject with himself) is basically dialogic, as it is an interaction mediated by language and other symbolic systems. Conscious- ness (as intra-psychological phenomenon) emerges then from the intersubjectivity, understood as mediated communication (Rosselli (2015).

Materials and methods

This investigation may be defined as an action research study that, according to Lingard (2008), it is commonly used for improving conditions and practices as part of the process. Carr and Kemmis (1986) also defined action research as a combination of ac - tion and reflection with the intent to change practice and theory (Mason, 2018).

General objective

To examine the use of scripted role-plays as a drama- based strategy to improve seventh grade students’ willingness to participate in speaking activities in English .

Participants

The action research was conducted in a Chilean subsidized school with a purposive sample of 38 stu- dents divided into 20 males and 17 females from 7 th grade, all of them aged between 11 and 12 years old with a level of English equivalent to A1 (elementary), according to the Common European Framework of Reference (Basic users). For this action research, seventh- graders participated in scripted role-plays as part of a drama strategy. The participants are part of the student body where 77 % of the educational community is at social risk. Six of these participants have special needs and behavioral issues.

Action research intervention plan

As a way to implement the strategy to be applied, seven sessions of ninety minutes each were planned. The research practitioner who conducted the study was the head teacher of the 7 th grade class:

Session 1 : Students identify the main elements of the script, such as characters and settings, then, become familiar with the role-plays by watching different videos about each particular play ( The Cat in the Hat and Peter Pan ), each video lasting 20 minutes each video. While they watch the movie excerpts, they have to take notes on the characters and the settings.

Session 2: Students analyze the scripts to familiarize themselves with language, structure, story lines, and pronunciation. Then they are divided into groups of at least 7 students each. Students analyze and organize, together with the teacher, the scripts given in terms of meaning and pronunciation (20 minutes per play). Students chose their roles for the play (the actors and the scenographers with one person to represent them).

Session 3: Students create the scenography for the role-play and rehearse the pronunciation and characterization of each role.

Session 4: Students judge their perception towards the scripted role-plays as a drama strategy on a scale to find out information regarding their willingness to participate in the speaking activities.

Session 5: Students participate in a focus group discussion.

Sessions 6 and 7: Students present their scripted role- plays.

Data collection techniques

As part of the data collection techniques, two different instruments were utilized:

In order to gather relevant data on the implemen- tation of the scripted role-plays, we simplified a Likert scale from Flórez, Pineda & García (2012) about motivation so that students could be able to understand it. It was accomplished in two dif-ferent sessions while the research was conducted (sessions four and seven). This instrument intend-ed to explore the students’ perceptions towards the scripted role-play speaking activities in the English class. The Likert scale of students’ percep-tions was made up of seven descriptors directly related to the students’ participation, willingness, and motivation toward the scripted role-play. Students had to assess their perception of the de-scriptors and rate them according to the follow-ing categories: Strongly agree, Agree, Strongly disagree and Disagree.

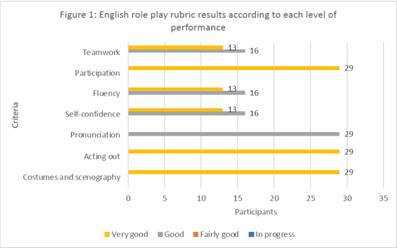

The second instrument used to collect data to de-scribe the effects of scripted role-plays as a drama strategy was an analytic rubric, consisting of six different criteria such as Costumes and scenogra-phy, Acting Out, Pronunciation, Self-confidence and Fluency, Participation and Teamwork.All of the different criteria were awarded four points each (1 = In progress / 2 = Fairly good / 3 = Good / 4 = Very good) and a total score of twenty-eight points.

Data analysis techniques

For the proper analysis of the data collected, frequen-cy and percentage analysis were used. A wide variety of graphs is used to describe and interpret the data that come from the Students’ perception scale and the analytic rubric.

Results

The following data analysis corresponds to each in-strument applied during the intervention sessions. In order to give a specific description of the findings, each instrument will be described according to the three specific objectives set for the research.

Specific objective 1: To describe the effects of scripted role-plays as a drama strategy by the end of the intervention.

Participants’ role-plays were evaluated using an ana-lytic rubric of seven criteria. Five criteria related to their performance and use of the language during the process of the intervention: Costumes and scenogra-phy, Acting Out, Pronunciation, Self-confidence and Fluency; the two other criteria were Participation and Teamwork during the implementation of the strategy. Figure 1 below represents the participants’ achieve-ment level by granting them a score for each criterion on the rubric used to assess the students’ performance after the implementation of this study:

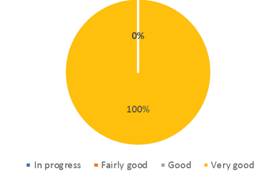

Costumes and scenography criterion

Figure 2 illustrate the percentage of participants that scored 4 points in the Costumes and scenography criterion. All of the students effectively prepared their scenography and costumes for each role-play. Furthermore, this increased the opportunities for them to successfully characterize each role by having all the resources needed to gain self-confidence and perform as expected (See Figure 2):

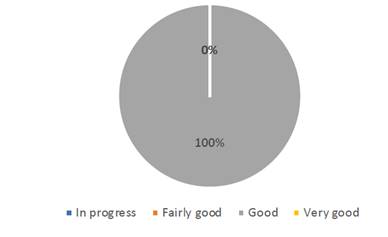

Acting out criterion

Figure 3 suggests that all the participants in this study scored 4 points in the Acting out criterion. It was observed that, when performing the role-play during the last session, students had already added extra lines to their characters to express and show vivid emotions that they felt necessary to highlight from each character (See Figure 3):

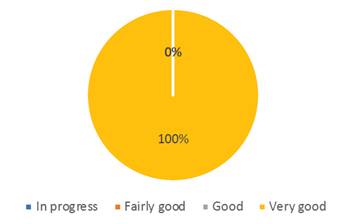

Pronunciation criterion

Figure 4 illustrates the students’ performance in terms of Pronunciation. It was observed that all the participants pronounced clearly throughout the role-play performance, which contributed to the communication and understanding of the exchanges among each member. Even though they did not have perfect pronunciation, they were able to convey the audience a clear message, which was consistent with their preparation (See Figure 4):

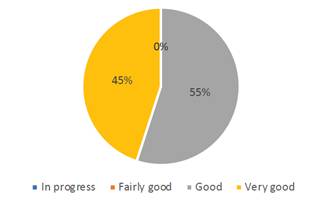

Self-confidence criterion

Figure 5 represents the results on the Self-confidence criterion. It illustrates that 16 students (55%), who represented group two, scored 3 points, since the tone and volume of voice in one or two members of the group was not the most suitable for the performance. On the other hand, 13 students (45%), who represented group one, scored 4 points, since they all visually interacted each other and used a perfect volume (See Figure 5):

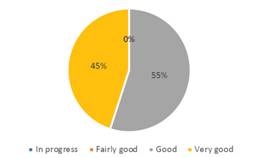

Fluency criterion

Figure 6 reveals students’ performance in terms of fluency during their final performance. As shown in the graph below, 13 students (45%), who represented group one, scored 3 points, mainly because one or two members made long pauses throughout the roleplay. On the contrary, 16 students (55%), who represented group two, scored 4 points (See Figure 6).

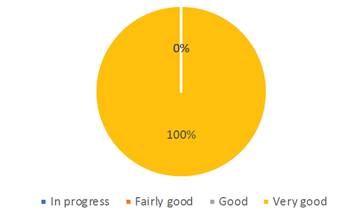

Participation criterion

As illustrated in Figure 7, the Participation criterion had a maximum of 4 points. Results suggest that student participation was 100% during the implementation of the strategy. They used each session planned to prepare all the necessary requirements such as the scenography and scripts modification with their group support. Despite the fact that unplanned situations such as disagreements emerged, they were able to solve them by facing their differences, using as an argument that “it is for the sake of the play and our mark” (See Figure 7):

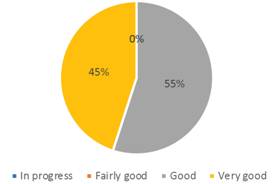

Teamwork criterion

As shown in Figure 8, results have proved that group two’s commitment to their own task was remarkable, since they achieved the total number of points, representing 45%. In addition, all participants worked collaboratively during the preparation of the play in most of the sessions and each member of the group contributed to the optimal development of the play. Regarding group one’s commitment, one may say that their work was not observed as a consistent practice in some members’ attitudes in terms of the development of their own roles in the role-play, especially when modifying scripts and preparing their scenography (See Figure 8):

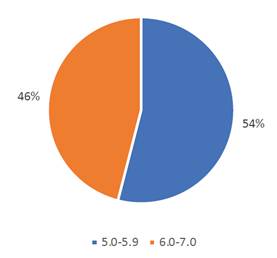

Participants’ final grades in the role-plays

Figure 9 shows students’ results in terms of marks. Students graded themselves as a group, and not as individuals, obtaining a single mark for the whole group. An analytical rubric had to be created to grade the students’ performance. The results showed that 46 % (group one) of the students got a mark between 6,0 - 7,0 (on a scale from one to seven). On the other hand, 54 % (group two) of the students got a mark between 5,0 - 5,9. The difference between their grades lied mainly on their performance in Fluency, Self-confidence and Teamwork (See Figure 9):

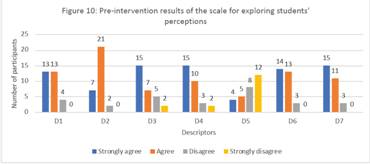

Specific objective 2: To explore students’ perceptions towards the scripted role-play strategy during the English class

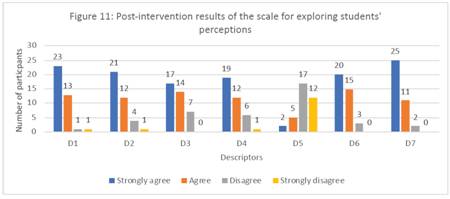

To explore the students’ perceptions towards the strategy implemented, participants had to answer a Likert scale in sessions four and seven. This scale had seven descriptors intended to evidence students’ perceptions. For them to express their point of view on each of the seven descriptors, they had to choose only one option from four levels of performance: Strongly agree, Agree, Disagree, and Strongly disagree. Figure 10 shows the pre intervention results from the scale on students’ perceptions. There was a strong tendency to answer Agree and Strongly agree in some of the descriptors from the scale.

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 11 below illustrates there is a significant increase in the students’ perceptions to move from Disagree, and Strongly disagree to Agree and Strongly agree. In descriptor 1, most of the participants chose Strongly agree and Agree. This result might suggest that their motivations towards the English class was mostly positive. In descriptor 2, 33 students out of 38 felt more willing to participate, mostly choosing Strongly agree and Agree. This tendency of choosing between Strongly agree and Agree is presented in descriptors 3 and 4 as well (See Figure 11).

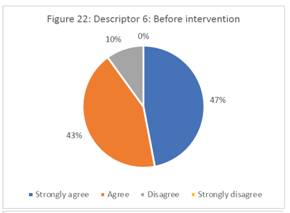

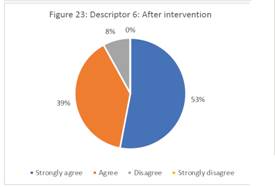

The results show that most of the students had a positive attitude towards the strategy. They also suggest that this attitude may eventually relate to their involvement during the sessions. This can be compared using both Figure 10 and Figure 11, where Strongly agree increased in number of participants after the scripted role-play strategy was implemented, as shown in descriptor number six. In it, during the first stages fourteen students chose Strongly agree on the statement I actively participated in the scripted roleplay this month, while at the end of the study twenty of the participants claimed that they Strongly agree on the same statement. This clearly emphasized how involved they felt while participating in the class.

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 11: Post-intervention results of the scale for exploring students’ perceptions

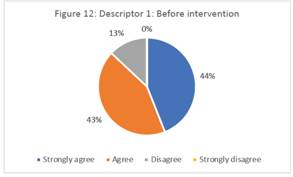

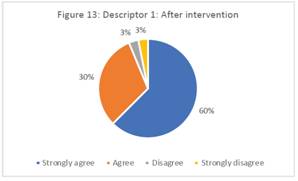

Descriptor 1: The scripted role-play has motived me to participate in the English class

In order to express the results for the descriptor The scripted role-play has motivated me to participate in the English class, Figures 14 and 15 show the percentage of participants that chose each answer. Figures 15 and 16 above describe the main differences found in descriptor number one after the first and last implementation of the scale on the students’ perception. On this descriptor, students’ answers of the descriptor moved mainly from Disagree (13%) before the intervention to Strongly disagree (3%) after the intervention. Nonetheless, in terms of Agree and Strongly agree, there was an increase from 9% in the first implementation to 14% respectively in the second implementation of the instrument. These results show that, at the end of the implementation of the strategy, there was an increase in the students’ motivation in comparison to the first implementation of this data collection instrument. For this descriptor, the positive results have proved the effectiveness of the scripted role-play strategy to foster motivation (See Figures 12 and 13):

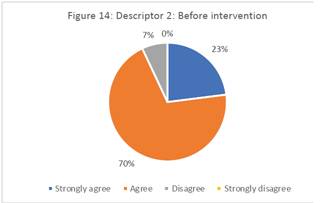

Descriptor 2: I felt more willing to participate when I had a global understanding of the scripted role-play

Figures 14 and 15 clearly show the dramatic increase from Agree to Strongly agree by 34% in the descriptor related to how willing students felt when they were able to understand the scripted role-play (See Figures 14 and 15):

Source: Own elaboration

Source: Own elaboration

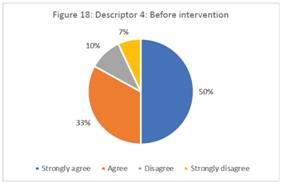

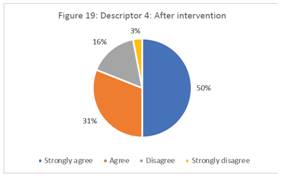

Descriptor 4: The language and complexity of the script used in class motivated me to keep working on the subjectFigures 18 and 19 correspond to descriptor 4 on the language complexity of the script used in class. This descriptor intends to measure how motivated the students felt to work with the complexity of the language and the script chosen during the sessions. Figures 18 and 19 also compared how the language and complexity of the script used in class motivated students to keep working on the subject. The results show that 4 % of the students moved from Strongly disagree to just Disagree and the responses to the Agree criterion decreased 2 %. This meant a positive impact, as fewer students felt identified with the present descriptor (See Figures 18 and 19):

Source: Own elaboration

Source: Own elaboration

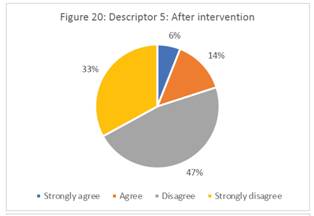

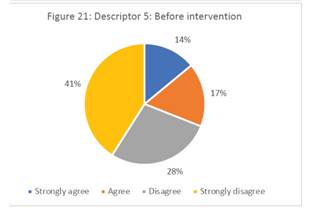

Descriptor 5: I felt discouraged when I didn’t understand what to do / or the instructions of the scripted role-play

In order to explain descriptor 5, Figures 20 and 21 present information in terms of how discouraged the students felt during the intervention. One must mention that each percentage corresponds to the number of students that chose the answer. As part of the results found in Figures 20 and 21, evidence showed that students did not feel discouraged when they did not understand the instructions of the scripted roleplay. As stated above, at the end of the implementation of the action research, only 6% of the students felt discouraged; while 33% of them responded Strongly Disagree on the descriptor, the other 47% disagreed with the same statement (See Figures 20 and 21):

Source: Own elaboration

Source: Own elaboration

Descriptor 6: I actively participated in the scripted role-play this month

Figures 22 and 23 represent the students’ responses to their own perceptions towards their active participation in the scripted role-play strategy. The results show that during the first implementation of the scale on students’ perceptions 47% of them Strongly agree on descriptor 6, while in the second implementation of the same statement, 55% of them Strongly agree. On the other hand, when talking about disagreement, the percentage was very similar (See Figures 25 and 26):

Source: Own elaboration

Source: Own elaboration

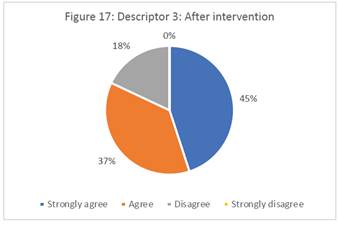

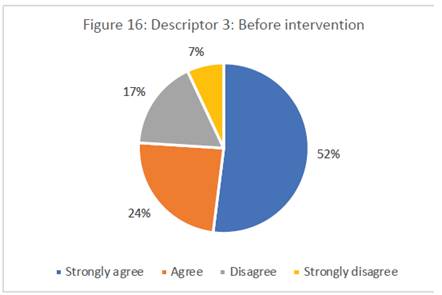

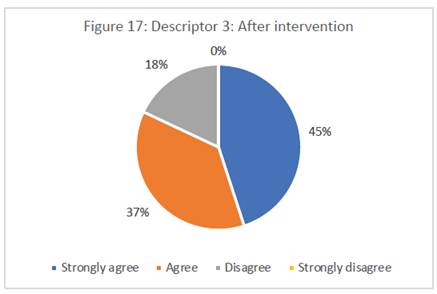

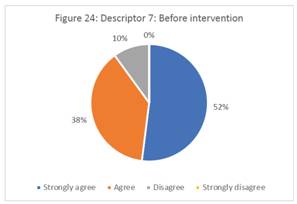

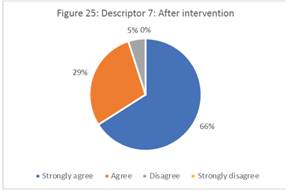

Descriptor 7: I followed the teacher’s observations and recommendations for the different sessions of the month

Descriptor 7 intended to explore the students’ perception towards the teacher’s recommendations to improve their work. On this matter, it shows that during the first implementation of the scale for exploring students’ perceptions, only 52 % of the participants state they Agree on the descriptor exposed, while on the second implementation, 66% of them answered Strongly agree. This shows that by the end of the implementation, they followed their teacher’s observations on their work. Nonetheless, there was 5% of them that did not agree with the fact that they followed the teacher’s recommendations for their improvement throughout the role-play preparation (See Figures 24 and 25):

Discussion

The findings will be discussed according to each specific objective.

Specific objective 1: To describe the effects of scripted role-plays as a drama strategy by the end of the intervention

The first specific objective aimed to describe the effects of the intervention strategy by applying an analytic rubric to evaluate the students’ performance. Participants were expected to successfully perform, prepare and act the scripted role-play strategy implemented. The findings suggest that all the participants had a strong commitment with role-playing. However, students were not able to achieve the highest s-ore (4 points) in the criteria corresponding to Self-confidence, Fluency and Teamwork.

Regarding Self-confidence as one of the criterion in which some participants did not achieve the highest score, it was observed that both groups had an issue communicating their differences in terms of how to approach the work to be done during the first session. This lack of communication was mainly due to some group members’ low self-confidence. They expressed they were not as good as their other classmates, who could speak or understand English better. Therefore, they were shy when talking in front of the rest of the group. Prada (2015) states that, when a foreign language learner is going through this learning process of acquiring a foreign language, it becomes difficult to speak the language or express themselves freely and fluently without some degree of self-confidence. Fortunately, this did not affect the whole group’s environment when working, but only a few students, particularly those participants who felt a higher level of commitment to use their English. The participants were able to use their leadership skills to sort out the problems and give enough confidence to their peers in order to prepare what was needed and required for each member involved in the team.

In terms of Fluency, it was observed that participants’ performance on this matter was influenced by their self-confidence and fear of being embarrassed in front of the class. After they performed each scripted role-play, some of the students expressed that it was very difficult to perform in front of the whole class by wearing costumes, mainly because they felt that their classmates would laugh at them. This fear of being embarrassed led one group of students to make longer period of pauses when interacting in the scripted role-play final performance.

When students work in groups, there are several factors that help them to overcome their individual weaknesses. These factors are closely related to the opportunities they are given to interact, make mistakes, and receive feedback on their work by their peers. Ibrahim, Syafiq, Mohd, Ismail, Dhayapari, Perumal, Zaidi & Yasin (2015) express that, in this way, students will be encouraged to be more objective and democratic in coming to a decision, especially when developing the ability to become an effective participant in conversations.

Specific objective 2: To explore students’ perceptions towards the scripted role-play activities during the English class.

Regarding the first descriptor on motivation to participate in the English class thanks to the scripted roleplay, 66% of the students Strongly Agree and 34% Agree on the statement presented at the end of the last session. Students showed that, while they were exposed to the use of scripted role-plays, they were willing to share and interact, even though this implied exposing themselves to embarrassing situations because of their own characteristics or limitations as individual learners, such as their inner motivation and specific skills required for acquiring a foreign language within a large group as presented in this particular context. Some of the most tense moments were while creating the scenography, modifying the scripts and rehearsing with their peers.

The high percentage of students who answered positively about their motivation was due to the implementation of the scripted role-play strategy, since they were able to overcome those critical moments of the process as individuals who acted as part of a team. Liu (2010) claims that “motivation colors and shapes students’ involvement in learning and it stimulates feelings that students associate with these experience” (p. 137). The enthusiasm shown by the students reflected their hard work to prepare and perform a good play.

Despite the high percentage of students who showed a positive attitude in their participation through the role-plays, not all of them felt the same. We observed that some of the students that were reluctant to participate as actors preferred to work as scenographers, leaving aside the responsibility of getting involved with the peers who seemed to enjoy acting and speaking in English with their classmates. Ross, Lasso & Quintero (2012) state that “introverted students have a clear disadvantage when it comes to English oral interaction” (p. 5); it is for this reason that providing the students with the appropriate atmosphere for the learning experience and the right materials would encourage them to participate despite the aversion they had to the English subject because of their previous experiences. Ross, Lasso & Quintero (2012) also claim that the variation of material, as well as the usage of contextualized topics, “make the students feel confident and motivated, and they start to get involved in the activities proposed by the teacher; consequently, it is evident the need to describe what kind of tasks and tools can be used in the language class for this student involvement to happen” (p.12).

In brief, the implementation of a scripted role-play based on a drama strategy has proved to be highly effective to improve students’ willingness to participate in speaking activities in English. Even though the participants faced communication and self-confidence problems, one may say that they managed to solve their differences, and, finally, 100% of participants prepared and participated in the scripted role-play. It is important to mention that these results cannot be generalized to other teaching contexts because this is an action research study conducted in a specific socio-cultural setting.

Regarding the results obtained for specific objective 1 (To describe the effects of scripted role-plays as a drama strategy by the end of the intervention), all of the participants showed great commitment as a team and actively participated during the sessions. The participants’ focus lied on the social interaction when using the scripts and creating the scenography. On specific objective 2 (To explore students’ perceptions towards the scripted role-play activities during the English class), these results revealed that students’ perceptions towards the scripted role-play were highly positive, since according to the outcomes, some of the students reported that, thanks to their classmates and teacher’s help, they did not feel unmotivated to participate. They claimed that being guided and supported by the teacher kept them motivated; they also mentioned that, due to the characteristics of the strategy (working in groups, creating scenography and facilitating role of teacher), they improved their knowledge of the English subject.