1. Introduction

Scholars have shown considerable interest in the study of executive pay, especially in recent years (Adu-Ameyaw et al., 2021; Li, 2020; Sirkin & Cagney, 2022). Executive compensation is strategically important because it helps attract, retain, and motivate talented executives in the medium and long term, which can then have an impact on competitiveness and organizational performance. However, there are sometimes issues with the structure of remuneration, particularly in relation to deferred compensation and supplementary pension plans (Ayuso et al., 2020; Duque-Ospina, 2016; Horton et al., 2021).

This study focuses on the internal and external determinants of supplementary pension plans (SPPs) and their effectiveness as a compensation practice in multinational and multi-Latin companies.1 More specifically, it explores the use of SPPs in the case of executives’ compensation, due to their rare and unique conditions (Dyer, 1993; Frydman & Jenter, 2010) from a medium- to long-range strategic perspective (Carpenter & Sanders, 2004; Horton et al., 2021). Interest in this research question first arose from the authors’ experience in this area. The initial proposition is that the inclusion of incentive schemes based on SPPs can be of high strategic value to organizations. They are supposedly a key compensation instrument, if properly designed, because they can align organizational aims with the specific goals of executives. They can play a central role in attracting, retaining, and motivating talented executives.

As a form of compensation, SPPs have become increasingly popular since the first half of the 20th century, especially in large companies. There are also numerous 21st century examples of the use of SPPs. Multilateral organizations such as the United Nations (UN, 2009), the World Bank (WB, 2012), the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2011), the International Monetary Fund (Clements et al., 2016), the International Labour Organization (ILO, 2018), etc., indicate that this practice has become more prevalent and that SPPs are important for providing resources for people as they get older.

For instance, at the World Bank (2012), SPPs constitute the voluntary pillar of its three-pillar model for executive compensation practices. There are four main reasons for this choice: (a) the growth of an aging world population; (b) the large reduction in the income of senior managers at the time of retirement; (c) the challenge of designing remuneration programs that maintain the standards of living of retired executives; and (d) the potential impact on organizational performance.

SPPs have become especially important to respond to the evolution of public pension systems. Driven by growth in life expectancy, parametric pension reforms are being implemented to reduce the replacement rate or coverage at the time of retirement and address what is known as the pension gap (Kessler, 2021; Peris-Ortiz et al., 2020; Yen, 2018). This gap is especially large for senior managers. Therefore, compensation plans that include company contributions to SPPs may become even more attractive. This research explores the relationship between the problems of public or private mandatory pension systems and company SPPs.

Qualitative analysis was used to achieve the research aims. The analysis method combines a thorough review of the specialized literature with data analysis based on grounded theory (Glaser & Straus, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). The data were obtained from 33 in-depth interviews. These data were combined with internal documentation from the companies and institutions where the interviewees were conducted. It was hoped that the inductive process based on this methodology would contribute to the literature by revealing new constructs and relationships from the data.

The results of the analysis advance knowledge of internal and external factors that encourage the use of SPPs as an instrument for attracting, retaining, and motivating senior managers. This compensation practice has considerable potential given the expected evolution of public pension systems. The results also lead to propositions for empirical testing in subsequent research. Finally, suggestions are offered to make SPPs more effective.

The following section contains a brief review of the theoretical background of SPPs. The third section explains the method, research design, data collection process, and analysis strategy. The fourth section details the key empirical findings and presents a set of propositions derived from the analysis. Finally, the conclusions and proposals for future research are outlined.

2. Theoretical background

From a human resource management (HRM) perspective, SPPs are a deferred payment that companies make indirectly to recipients through a third party. This third party may be a private pension fund or a fiduciary in charge of managing resources. There are two main types of SPPs: defined benefit SPPs, which seek to guarantee a specific supplementary pension value, and defined contribution SPPs, where the objective is to support a supplementary pension but no commitment is made by the company regarding the value of the pension.

In contrast with the findings of authors such as Milkovich and Newman (2004) , the evidence from the authors’ professional practice and research is that SPPs are not only protection programs but also long-term incentives linked to organizational performance. In the case of senior executives, performing well in a top management position requires a high degree of skill development and specific knowledge. It also needs a comprehensive overview of the business model, the environment, and the global situation. Barney (1997) , Dyer (1993) , Lepak and Snell (1999) , and Pfeffer (1994) describe senior executives as valuable and unique resources, reporting that they are fundamental as creators of strategic value and competitive advantage.

Global business dynamics, competitive pressures in markets, competition between companies for the same customers, the proliferation of new technologies, changes in consumer trends, and the demand for increased productivity for organizations to survive and prosper have led to fierce competition among large companies to attract and retain talented managers, given their impact on business performance (Duque-Ospina, 2016). Accordingly, companies need new solutions to ensure long-term commitment and retain managerial talent. In recent decades, the literature has cited SPPs as a potentially effective compensation practice for attracting and retaining much-needed managerial talent (Aguilar, 2000; Cadman & Vincent, 2015). This phenomenon has been analyzed from different perspectives.

From an agency theory perspective, contracts are what formalize and align the interests of owners and managers (Buigut et al., 2015). For organizations, those in senior management positions must have a long association with the firm to create, conceive, develop, and implement the strategies that allow it to grow, make a profit, and be sustainable. Research has shown that contract duration can be affected by compensation practices (Dechow & Sloan, 1991; Kole, 1997; Sappington, 1991; Stroh et al., 1996). By their very nature as deferred benefits that are subject to performance and permanence, SPPs can be useful for retaining senior managers. In long-term relationships, companies and executives can both benefit from linking compensation to performance (Bebchuk & Fried, 2003; Boschen & Smith, 1995). Therefore, it seems sensible to link a company’s SPP contributions to performance.

From a stakeholder theory perspective, compensation schemes can resolve principal-agent conflicts. However, they can also shape the actions of senior managers, who have an influence on the design of their own compensation schemes, ensuring that they make decisions that satisfy the needs of other stakeholders. The scandals of companies with fraudulent accounting practices such as Enron, WorldCom, and Arthur Andersen resulted in losses for thousands of investors. These examples, show the importance of generating adequate organizational guidelines for manager compensation and control (Berrone & Gómez-Mejía, 2009; Chapas & Chassagnon, 2021). Whatever the case, managerial compensation schemes must adapt to the internal and external organizational context. They are an integral part of an organization’s strategy. As much as possible, they should reflect the preferences of employees (Gómez-Mejía & Balkin, 1992; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2014; Milkovich, 1988).

The internal and external factors that condition compensation structure are highlighted in the literature. Internal factors include company size, company maturity, organizational culture, organizational structure, revenue, performance, business model, human resource strategy, corporate governance, company value, and employee characteristics related to corporate culture and people’s individual life cycles (Devers et al., 2007; Gómez-Mejía & Wiseman, 1997; Lee & Chen, 2011; Milkovich & Newman, 2004; Sánchez, 2001; Tosi et al., 2000). External factors include sector, the competitive environment, the economic cycle, cultural variables, and legislation (Gómez-Mejía & Sánchez-Marín, 2006; Grund & Tanja, 2015; Katalin, 2014; Zou et al., 2015). Although all of these factors are important when researching this topic, few studies have examined the factors that affect the degree of SPP use and the specific SPP model and its effectiveness. Hence, inductive qualitative analysis was used, as detailed in the following section.

3. Methodology

This research has an exploratory purpose and therefore uses qualitative methodology. It is not strictly a case study, but it largely follows the guidelines for this type of analysis, given the nature of the research question (Swanborn, 2010). Background knowledge of this social and economic phenomenon in a specific context formed the basis for the research. The research team’s interest in individual and group behavior allowed the research team to address a range of research questions. The chosen method is especially appropriate when the topic has been the subject of little research, as is the case in the present study. The analysis of SPPs as an instrument for attracting, retaining, and motivating managerial talent involves the study of varied and dynamic processes. It involves complex variables that are difficult to measure, as well as elements of individual and family behavior. It is also influenced by organizational context and the social environment. It consequently requires a detailed prior review of SPPs and their context.

This study examines SPPs as a compensation practice. It focuses on the case of managers at multinational companies with a subsidiary in Colombia or multi-Latin companies of Colombian origin. However, given that SPPs and public and private pension systems in Colombia are closely related, it makes sense to study them comprehensively to explain pension dynamics. Consequently, Pillars 1 and 2 of the World Bank model are used for the analysis. These pillars are: (1) a mandatory defined benefit public pension and (2) a mandatory defined contribution private pension.

Data collection was based on a protocol, interview scripts for each type of informant, and a data collection form for documentary sources. The aim was to enhance data collection by standardizing the processes to ensure validity and reliability (Bonache, 1999; Miles & Huberman, 1994; Yin, 2009). The data were collected between the second half of 2015 and the first quarter of 2016. The main data collection technique was in-depth interviews with different types of agents. The review of documentation complemented the interview data and enabled triangulation of the information gathered in the interviews. Appendix 1 lists the document sources. As per the protocol, the interviewees were informed of the use of the data that they provided. They were also informed of their commitment to the study, the time that they would need to spend on the study, and other such details. Two documents were prepared for this purpose. The first explained these issues. The other collected their informed consent.

To select the sample of interviewees, all possible combinations were represented in terms of degree of use of SPPs as an executive compensation practice and the contribution to executive pensions in Pillars 1 and 2 of the World Bank model. Interviewees were executives responsible for the decision to offer an SPP to managers, managers responsible for SPP design and management, and managers who were beneficiaries of an SPP. Interviewees included CEOs, vice-presidents of human resources, and overall senior executives of multinational companies such as Colgate, Johnson & Johnson, Smurfit Kappa, Mondelez, and large multi-Latin companies with a strong international presence such as Carvajal, Sura Insurance, Tecnoquimicas, and Promigas. Researchers, private and public fund managers, and representatives of multilateral institutions such as the Director for Latin America of the OECD in Paris and the Inter-American Development Bank in Washington were also interviewed. These interviewees were selected because of their knowledge of public and private pension systems and because of the possible existence of complementarities, interactions, and interdependencies.

The interview script was flexible for three reasons. (a) The interviewees were high-level managers who were difficult to contact. Therefore, the research team wanted to ensure that any opportunity to interview these individuals provided the maximum data in terms of opinions or recommendations. (b) The subject matter was complex, so during the interviews, new items might have appeared. (c) The topic of study was related to the recent history of the organization and the interviewee. Therefore, the interview covered feelings and highly personal aspects of the interviewee’s family life.

As in grounded theory, the sample was determined by the categories and emergent theory (Coyle, 1997). Data collection and analysis took place almost simultaneously. From the first stage of data collection, new codes and categories were generated. The researchers decided what type of new information was necessary, what new agents had to be interviewed, what changes to the interview guide should be made, what kind of supplementary information was needed, and other such considerations. Consequently, the researchers were unable to set the sample size prior to data collection. Instead, the sample expanded depending on the new information that was needed until saturation was reached. Saturation occurs when no new codes or categories emerge (Glaser, 1992). Initially, 22 interviews were planned. Finally, 33 interviews were conducted (see Table 1) to ensure data saturation (Hennink & Kaiser, 2020).

Table 1: Interviewee profile and number of interviews

| Code | Interviewee | Number of people by position | Number of interviews per person | Estimated average duration in hours |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | CEOs and boards members: decision makers and beneficiaries | 9 | 1 | 1 |

| (2) | Human resource managers and vice-presidents: decision makers, beneficiaries, and those responsible for compensationissues | 9 | 1 | 1.5 |

| (3) | Other managers: beneficiaries | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| (4) | Representatives of multilateral institutions: analysts and researchers | 3 | 1 | 1.5 |

| (5) | Professors: researchers | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| (6) | Private fund managers (2) Public fund managers (1) National bank (1) | 4 | 1 | 1 |

Source: Authors

The data from the interviews were gathered from more than 40 hours of recordings. These recordings were transcribed literally for further analysis. The transcripts covered more than 400 pages of text. This process ensured precision and compliance with the quality standards for this type of research. As mentioned earlier, the data were supplemented with data from document sources. All data were analyzed independently by two researchers to reduce researcher bias. The analysis procedures recommended by Miles and Huberman (1994) , Swanborn (2010) , and Yin (2009) were followed.

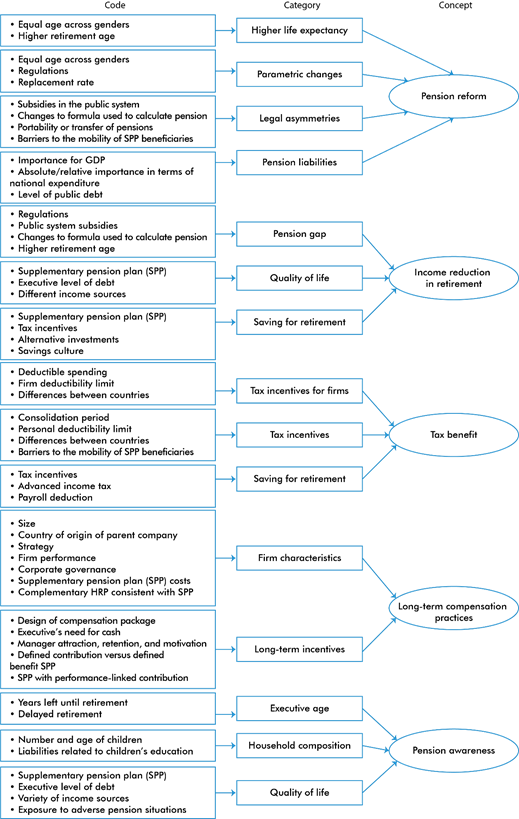

The analysis to establish codes, categories, and concepts had four steps. In Step 1, each researcher openly and independently coded the data based on a priori codes following the review of the existing literature and the practical experience of the researchers in this field. In Step 2, the results were discussed between the two researchers until they reached an agreement. Then, the final codes were established. In Step 3, categories were created based on the codes, and core concepts were defined. In Step 4, the information was processed in ATLAS.ti version 7 to visualize the data classified by final code. This approach produced a visualization of the relationships. This process gave the researchers a better understanding of the study aims and identified the key internal and external determinants that, according to the data, conditioned the use and the success of SPPs for attracting, retaining, and motivating talented managers. The propositions presented in the following section summarize the findings.

4. Results

Five core concepts were identified: (a) pension reform, (b) reduction in income at the time of retirement, (c) tax benefits, (d) long-term compensation practices, and (e) pension awareness. Figure 1 shows the structure of the data and a summary of the codes and categories related to these five concepts.

Pension reforms offer opportunities to strengthen SPPs. Pensions are likely to shrink, particularly those of high income individuals. Nevertheless, parametric pension reforms tend to focus on reducing pension benefits through measures such as expanding regulations, reducing subsidies, and lowering replacement rates. Evidence of these changes can be found in the OECD (2021) report Pensions at a Glance 2021. In its Pension Outlook 2022 report, the OECD advocates strengthening pension systems with a multi-pillar system that combines different types of complementary pension schemes to diversify risks. SPPs are central to this proposal.

The evidence seems to show that pension reforms increase the need for private pension plans for the target group in this study. This compensation practice could have positive effects on organizational results. Making SPPs more attractive could improve a firm’s ability to attract, retain, and motivate senior executives and other strategic employees. These employees have rare, specific, and valuable competencies that can lead to sustainable competitive advantage. The resource-based view of the firm offers a theoretical basis for this proposition (Barney, 2001; Barney & Clark, 2007; Carey, 2008). The analysis of the interviewees with professionals supports this idea.

“One of the basic purposes of the pension system is the redistribution of wealth, and, accordingly, a reform would further reduce the pension income of top executives (…). To the extent that there is a reduction in pension instalments, SPPs will become important to attract and retain (talent).” MI-2

One interesting phenomenon among the companies in this study was that executives often did not want to retire at the age stipulated by Colombian law. This phenomenon was not foreseen at the beginning of the study. Instead, they behaved differently from people in other segments of the Colombian population, who disagreed with pension reforms that would potentially increase the retirement age. As noted by one of the interviewees:

“The pension gap is a major concern for them because the decrease in income is severeFor this reason, many of them are working for longer.” HRM-2-MN-USA-2

Accordingly, the advantages, drivers, obstacles, and impediments of implementing SPPs are important. First, the advantages result from the design of a long-term incentive that depends on the achievement of organizational goals. Second, the transformation from short-term pay mechanisms to variable long-term pay would have a positive impact on corporate cash flow (Pepper et al., 2013). SPPs could therefore help align the interests of firms and executives, reducing the potential agency conflict (Cieślak, 2018; Eisenhardt, 1988, 1989; Reid, 2018). The following interview quotation illustrates this idea:

“Each compensation package has purposes and objectives that seek to mobilize certain employee behaviors that benefit both the employee and the organization (…). Long-term incentives (including SPP contributions) are intended to promote long-term thinking, align executives’ interests with those of shareholders, and attract and retain talented executives.” HRM-1-ML-COL-1

Regarding obstacles, the reduction of income after retiring makes saving for pensions a social and organizational goal. Companies have begun to understand that it is better to emphasize long-term compensation for the future because of its potential effect on organizational performance from a strategic perspective. However, executives that need resources to ensure cash flow demand short-term incentives. Intensive consumption and high standards of living are obstacles for the implementation of SPPs because they increase expenditure and indebtedness, reducing executives’ acceptance of receiving deferred payment. As noted by one interviewee:

“To the extent that an executive accrues liabilities to maintain a high standard of living, SPPs become less attractive.” BM-NB-COL

Therefore, the challenge is for executives to be willing to sacrifice short-term income. This willingness is considered unlikely in the absence of tax incentives. The evidence supports this assertion.

“The implementation of an SPP must go hand-in-hand with a number of incentives to attract managers that in some way will be positive for the firm and the individual.” BM-ML-COL-2

Besides indebtedness, other personal factors that negatively affect the attractiveness of SPPs and the willingness to save are the number of descendants or economically dependent family members in general. These family burdens increase the need for short-term cash flow, limiting executives’ ability to save for retirement. The following comment exemplifies this situation:

“Up to the age of 40 or so, an immediate profit or cash flow is more desirable for a manager, since he/she is in the process of starting a family, building wealth, and raising children.” OM-ML-COL-9

Pension awareness is a key antecedent because it implies a greater willingness to save and makes SPPs attractive. It is also important because, over time, the temptation to consume will increase. As noted by one of the interviewees:

“The first step for an individual to ensure his/her quality of life in old age must be the awareness of the needs that he/she will have in the future and therefore the preparation to cover them with a savings plan from the beginning of his/her working life.” OM-ML-COL-3

Efforts to develop an elderly savings culture by public authorities and companies are considered essential to guarantee quality of life in old age and ensure SPPs’ ability to attract, retain, and motivate managers. The following statements illustrate this widespread opinion:

“The state/government has to implement saving education programs to train people to save money for the long term because a long-term culture does not exist”. PUF-COL

“Pension awareness is linked to evangelization and corporate discourse.” OM-MN-USA-3

The analysis of the interviews and other primary and secondary data also revealed that years remaining until retirement had an inverse relationship with pension awareness and the willingness to save for retirement. This finding is related to the differences in priorities and needs of people throughout their life cycle.

“For an older manager, in contrast, long-term retention plans work, since the aforementioned issues (marriage, housing, and child rearing) have already been solved and sustainability in his/her old age is the most important issue to be solved as soon as possible.” OM-ML-COL-6

Experiencing adverse pension situations caused by a lack of foresight and preparation of retirement increases pension awareness and willingness to save. As noted by Davis (1983) , an individual develops empathy through observed experiences. Contact with other people in distress makes it easier to put oneself in their place and reflect on how to deal with a problem.

“Being able to observe relatives or other pensioners who need their savings or SPPs to live in peace is a factor that helps make young managers aware of the need to have a savings plan for old age.” BM-2-ML-COL-1

The analysis also revealed the importance of firm characteristics related to the probability of SPP implementation and the extent of this implementation. SPPs are more common in larger firms, which is generally the case of multinationals and multi-Latin companies, as well as high-performing firms with a healthy financial structure.

“The top 400 are the most important leaders in the world and offer the most incentives of all kinds, including contributions to SPPs.” HRM-MN-UK

“A supplementary pension plan can bring cost overruns to companies, so the decision to implement it will be closely linked to their financial health.” HRM-ML-COL-9

These programs seem to be most highly valued and effective when firms take an active role in all aspects of retirement preparation by providing information, running training programs, and offering technical advisory services. The human resources (HR) area plays a key role in this area of retirement preparation because it can run campaigns to encourage savings, thereby increasing pension awareness. This factor is relevant not only in the sense that SPPs can attract, retain, and motivate talented executives but also from a social corporate responsibility (CSR) perspective (Anantharaman et al., 2021; Harjoto & Laksmana, 2021). The following comments provide evidence in this regard:

“The attraction and retention of managers with supplementary pension plans is a matter for human resources as it is directly responsible for planning pension awareness strategies and offering and implementing these benefits.” HRM-1-MN-USA-2

“The implementation of long-term SPPs should come after awareness and education sessions on the world of pensions for employees, since the understanding of what the pension gap is and how it affects the life of managers after retirement can awaken interest in savings for old age from an early age.” BM-ML-COL-7

From a macro perspective, it is essential to encourage saving, foster pension awareness, and think of future generations in terms of their compulsory pension. They will face wider gaps and lower incomes during retirement following the parametric pension reforms discussed earlier. Nevertheless, although these initiatives are of interest, they are usually not enough. They are relatively ineffective in terms of net growth of the savings rate unless accompanied by tax incentives. The data suggest that tax benefits are the greatest drivers of long-term savings:

“Tax changes are a key factor in this regard because they encourage, force, or prevent managers from allocating more resources to their pensions.” BM-MN-USA-2

Nevertheless, this initiative must be accompanied by other measures that prevent executives from simply consuming. Debt alternatives that use savings as a guarantee can lead to negative savings. After discounting their liabilities with banks, executives may not increase their capital for retirement. It is therefore necessary to separate tax benefits from the restrictive conditions of money saved for retirement, which receives preferential tax treatment to force executives to have an effective supplementary pension. Through the Ministry of Finance, the Colombian government has been reducing tax benefits for private pension plans since 2012. This policy has reduced the likelihood of future increases in benefits for this type of compensation. The consequence is that it also reduces the appeal of private pensions, so private pension funds will struggle to convince firms and individuals that they are still beneficial even without these tax benefits.

Analysis of the interviews and other primary and secondary data revealed the importance of other contextual factors besides tax benefits. Cross-country legal asymmetries hinder the implementation of SPPs in multinationals and multi-Latin firms. The reason is that, in many cases, these asymmetries create barriers to the international mobility of executives, who try to protect benefits obtained in countries with more attractive tax laws. The following quotations reflect this idea:

“Changes in the macro labor legislation of each country directly affect the structure of SPPs. The more standardized it is, the easier it is to implement SPPs in multinationals and multi-Latin firms.” BM-MN-IRL

“The tax asymmetry between countries causes problems for exporting talent (…). The mobility of managers, known as expatriates, is a key factor because, at Reckkitt, they move around the world very easily, but the concern is always what will happen to their pensions.” HRM-MN-UK

National culture is also relevant. Some countries have a culture of saving for retirement, whereas, in other countries, it is a secondary consideration at best. These cultural differences may be explained by Hofstede’s cultural dimensions of long-term orientation and uncertainty avoidance (Hofstede, 1991; Hofstede et al., 1990). In general, the level of use of SPPs is related to the pension culture and pension gap in each country. Thus, the level of use of SPPs seems to be influenced by the country of origin of the multinational or multi-Latin company, as well as the country where the subsidiary is located. Much evidence was found to support this idea. For example:

“There is a generalized practice in Latin American organizations of preferring short-term benefits, with the exception of Brazil and the United States, where people work from a young age to reduce the pension gap.” HRM-3-ML-COL-1

“The strategy of offering SPPs must consider differences in cultural profiles.” OM-MN-USA-3

“In ungenerous systems where the pension gap is greater, supplementary savings are very important.” MI-2

Finally, the analysis of codes, categories, concepts, and their linkages leads to a series of propositions. These propositions appear alongside supporting quotations in Table 2.

Table 2: List of propositions and supporting quotations of categories and their relationships

| Categories and their relationships | Supporting quotations |

| Proposition 1 | |

| The envisaged parametric pension reforms will increase the pension gap (i.e., reduce the replacement rate), increasing the appeal of PPSs and their ability to attract, retain, and motivate executives. | “(…) the public model requires a change and the prediction is a migration to self-sustaining private schemes but with lower pensions.” HRM-MN-UK “A pension reform is needed to give, to some extent, a solution to the financial crisis of the system (…) guaranteeing people the bare minimum.” BM-NB-COL “An SPP contributes to a good end of work cycle, since the reduction of the pension gap by an SPP helps people retire comfortably.” BM-MN-IRL “Closing the pension gap at retirement is an important objective.” HRM-ML-COL-9 “The fact that an organization is concerned with the future pensions of its employees (…) is an important element for retaining them.” BM-ML-COL-7 “The gradual extension of SPP coverage works as a retention strategy.” OM-ML-COL-6 |

| Proposition 2 | |

| The increase in the pension gap will increase the proportion of managers who seek to delay retirement, which may hinder the implementation of succession plans. | “(…) if, at the time of retirement, an employee is not in a good financial situation, he/she is also going to want to stay at the firm for longer. This situation hinders staff turnover and management team renewal.” MI-3 “Some people do not want to retire or delay retirement because they do not want to see their income reduced.” HRM-2-MN-USA-2 “An SPP helps people retire from their work cycle with a certain degree of peace of mind, since it reduces financial worries about old age and enables the company to recruit new talent by increasing the retirement income from savings.” BM-MN-IRL “At the time of retirement, a person who has an SPP has much more peace of mind in financial terms because his/her pension gap will be smaller, which will allow him/her to retire on time and give the opportunity to young people who follow.” HRM-MN-UK |

| Proposition 3 | |

| Lower tax incentives applied to SPP contributions are associated with a weaker appeal of SPPs as a means of compensation, reducing their ability to attract, retain, and motivate executives. | “Incentives must target legal persons so that they can be formalized.” BM-ML-COL-2 “It is important to maintain certain tax benefits to help people build their wealth and pension capital (…) The decrease of tax benefits reduces Colombian executives’ scope to save money for a pension.” HRM-2-MN-USA-2 “The existence of tax incentives would be a good strategy to promote savings for old age.” HRM-1-ML-COL-1 “Tax optimization is an important element in the valuation of an SPP (…). Tax benefits are a key factor in implementing and maintaining a pension plan.” HRM-MN-UK |

| Proposition 4 | |

| Greater efforts to develop a savings culture that enhances awareness are associated with a greater willingness to save money in the long run and therefore to the ability of SPPs to attract, retain, and motivate managers. | “Awareness of the fact that it is necessary to save money for retirement from the beginning of working life must be fostered from school and university to force a major cultural change regarding a savings culture.” OM-ML-COL-3 “Human resources can greatly contribute to creating a savings culture.” HRM-MN-UK “(…) a savings culture has to be fostered by companies through learning actions, with a message that can raise employees’ awareness.” BM-ML-COL-7 “(…) it is necessary to nurture a savings culture-to educate people to reduce running costs by saving part of their current income to finance retirement (…). Promoting saving awareness must be part of a firm’s integration process.” BM-MN-BEL |

| Proposition 5 | |

| The existence of legal differences between countries and the tax benefits that are offered will reduce the rate of use of SPPs for compensation in multinational and multi-Latin companies. | “This (legal asymmetry) is a major challenge given the wide differences between countries that make the implementation of SPPs (at multinationals and multi-Latin firms) difficult.” HRM-MN-UK “There are country issues such as legal regulations and strategies that are obvious and often prevent the implementation of a regional plan.” HRM-2-MN-USA-2 “At Kraft, there are no SPPs due to the difficulty of standardizing them (…). Such plans should be implemented in all of the international subsidiaries of the firm, but legal asymmetries make it difficult.” OM-MN-USA-3 |

| Proposition 6 | |

| The existence of these legal differences in cases where multinational and multi-Latin companies have implemented SPPs negatively affects executive mobility between subsidiaries located in different countries. | “(Legal asymmetries in SPPs) may even impede cross-country mobility because of benefit asymmetries.” HRM-2-MN-USA-2 “(…) sometimes, cross-country pension regulation asymmetries cause a contradiction (for executives) because they want to grow professionally but do not want to lose the pension benefit of their country of origin.” OM-MN-USA-3 “Achieving greater standardization across the labor regulations of different Latin-American countries would help the cross-country mobility of staff signed up to SPPs.” BM-ML-COL-2 “They have tried to bring people, even young people, from Brazil, and they prefer to stay there to keep their retirement plan.” HRM-MN-UK “Their SPP is difficult to restructure, which hinders mobility.” MI-3 |

| Proposition 7 | |

| The larger the company, the more widely SPPs are used for compensation. | “It (size) is crucial to develop and implement SPPs.” HRM-MN-UK “SPP costs depend on the size of the firm.” BM-ML-COL-7 “Not detecting a higher presence of this practice (SPPs) at large Latin American firms would surprise me a lot.” MI-2 |

| Proposition 8 | |

| National culture influences the use of SPPs and their ability to attract, retain, and motivate executives. | “Sense of welfare is a cultural question. In the USA, there is a strong culture of saving for retirement, which is why, in many firms, there are SPPs that benefit their employees.” BM-2-ML-COL-1 “Culturally, there is not a strong savings culture (in Colombia).” BM-ML-COL-7 “The culture of current generations in Latin America means that they are unattracted by a long-term savings culture, unlike what happens in the United States.” HRM-1-MN-USA-2 “Long-term awareness is a factor that is poorly rooted in the Colombian culture (…) which determines the need for awareness strategies for a better outcome in retaining executives with long-term SPPs.” BM-2-ML-COL-1 |

| Proposition 9 | |

| Businesses with a healthy financial structure and performance use SPPs more intensively in their compensation practices. | “The application and durability of long-term plans depend greatly on the financial situation of the firm (…). Only organizations that are financially stable, are able to pay, and have strong salary policies can offer long-term benefits to employees.” HRM-1-ML-COL-1 “(…) the financial crisis had a major impact on this percentage (firms’ contribution to SPPs).” HRM-1-ML-COL-1 “(…) creating new long-term benefits is complicated for a firm’s budget.” HRM-ML-COL-9 “Due to declining profits, companies tend to flatten their compensation plans.” BM-ML-COL-2 “The growth of the economy that brings profitability to companies (…) aids companies’ capacity to afford SPPs.” BM-ML-COL-7 |

| Proposition 10 | |

| Older executives have higher pension awareness, so the capacity of SPPs to attract, retain, and motivate them is greater. | “Generally, people do not think about their retirement and pension until they are very close.” MI-2 “It is a fact that young executives do not prioritize their pension, so pension awareness comes when they feel that retirement age is near.” BM-ML-COL-7 “The starting date to think about an SPP is about 10 years before retirement.” HRM-1-ML-COL-1 “More or less until your 40s, an immediate payment or cash flow is more appealing to managers given that they are usually starting a family, acquiring assets, and bringing up children. Later, their requirements and priorities change, and they start thinking about their old age. At this time, they develop a stronger saving awareness and hence interest in SPPs.” HRM-ML-COL-9 |

| Proposition 11 | |

| The higher the number of dependents in an executive’s family, the lower the savings capacity and therefore the weaker the capacity of SPPs to attract, retain, and motivate. | “Concern for SPPs depends on an executive’s life stage, so if he/she is bringing up children, he/she will prefer support for education at school and university in his/her compensation package.” MI-1 “Personal savings help retired people do recreational activities such as traveling because other expenses should be covered by their pension, assuming that they have raised their children and acquired assets before retiring.” HRM-ML-COL-9 |

| Proposition 12 | |

| The more debt executives have, the less attractive SPPs are, and the weaker their capacity to attract, retain, and motivate them is. | “The constant offering of loans to executives, whose payments are deduced each month from their salary, means that they can become highly indebted, which reduces their saving capacity.” HRM-1-ML-COL-1 “(…) I worry about debt alternatives whereby the resources saved for SPPs are delivered as a guarantee, given that they are very attractive because of their low cost in terms of interest rates, but ultimately they may lead to negative savings.” HRM-MN-USA-1 “Family wealth as a source of assets plays an important role in the life of pensioners.” BM-NB-COL |

| Proposition 13 | |

| The closer executives are to adverse pension situations, the higher their pension awareness is, and the greater the capacity of SPPs will be to attract, retain, and motivate them. | “(…) today, many of them (previous generations) do not have pensions, and their incomes are low or they have to live with the help of their children. Young people are actually becoming pension aware earlier because of their experience with this situation.” HRM-2-MN-USA-2 “The recognition of the need to ensure social protection for themselves has increased because of the rise of issues related to retirement and because of the negative observable effects of a lack of foresight in executives’ immediate environment.” OM-ML-COL-3 “Older people can teach young people about saving through their own experiences and through educating by example. So, new generations become aware earlier of the importance of long-term savings.” PUF-COL |

| Proposition 14 | |

| The implementation of an SPP has positive effects on pension awareness and therefore the capacity of the SPP to attract, retain, and motivate executives. | “When people have an SPP, they start to value it, regardless of age. (…) having an SPP immediately raises pension awareness. People start considering it part of their core assets.” HRM-2-MN-USA-2 “There is a general lack of awareness among managers, who believe that their pension will not be much lower than their salary. Therefore, they do not think about creating supplementary savings. The implementation of an SPP following awareness-raising days may change their perspective on the subject.” BM-1-ML-COL-1 “SPPs should be seen as a long-term challenge to generate income after retirement so that managers will be more attracted and willing to do it.” BM-ML-COL-2 |

Note: BM = board member; HRM = human resource manager; OM = other managers; ML = multi-Latin firm; MN = multinational; MI = multilateral institutions; PRF = private funds; PUF = public funds; NB = national bank; COL = Colombia; BEL = Belgium; USA = United States of America; UK = United Kingdom; IRL = Ireland.

Source: Authors

5. Conclusions

Public pension systems are evolving toward long-term sustainable models. This evolution will lead to parametric pension reforms that will adversely affect the interests of high-income senior managers. This situation can make SPPs increasingly valuable for retaining and motivating managerial talent, especially when used as an incentive linked to achieving organizational goals.

National regulations of SPPs (contribution limits, tax incentives, and portability/transfer of pensions) are key factors affecting the attractiveness and effectiveness of SPPs. Also, cultural elements appear to affect the appeal and adoption of SPPs. Thus, efforts by institutions to create pension awareness and build a savings culture are potentially important in boosting the adoption of SPPs. Companies can also make internal efforts in this area. For instance, they can propose other HRM practices consistent with the use of SPPs. One interesting target for future research could be to analyze such practices.

Factors such as an organization’s size, financial solvency, and status as a multinational or multi-Latin firm can also affect the level of use of SPPs. Future research should examine other factors such as competitive strategy and shareholder structure in influencing the use of SPPs. With regard to executive characteristics, family situation, consumption habits, level of debt, and exposure to adverse pension situations are key aspects that affect the potential of SPPs as a compensation tool to attract, retain, and motivate executives. The current situation seems to present a major opportunity for insurance companies and private funds to offer mass pension solutions and insurance coverage through large-scale distribution channels.

As next steps for research on this topic, studies should focus on detailed analysis of the type of SPP that provides the best results. The lessons learned so far indicate that SPPs appear to be an effective long-term alternative when the following conditions are met: (a) they are defined contribution SPPs; (b) both employee and company are obliged to make contributions; (c) the company contribution depends on the achievement of organizational goals; (d) abandoning the SPP is penalized; and (e) there are restrictions on the use of capital for purposes other than retirement.

Finally, despite not being a specific objective of this research, there are numerous cases of excessive long-term remuneration schemes, such as certain SPPs with abusive defined benefits. Examples can be found in major companies in Spain and the United States. In such cases, individual interests lie above the general interest. Scholars should play a more prominent role in debating this situation, adopting an impartial and critical look at these types of abusive and unfair practices.

Future research should continue to study the range of techniques in public and private pension systems. Taking this focus as a starting point, studies can contribute to the debate on the future of pensions, a vital subject for society as a whole. Scholars should also look to identify elements to make SPPs more easily transferable, such as environmental factors that encourage SPP practices. Finally, the propositions enumerated in this paper should be tested using quantitative research so that they can be generalized or refuted.