Exercise is a key component in the management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM). Previous studies have provided supportive evidence for the use of prescribed exercise programs in the treatment of Type 2 Diabetes (Balducci et al., 2014; Church et al., 2010; Maiorana, O'Driscoll, Goodman, Taylorb and Green 2002; Dunstan et al., 2002; Sigal et al., 2007; Taylor, Fletcher and Tiarks, 2009). The American Diabetes Association (ADA), American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and American Heart Association (AHA) have published position statements recommending the use of exercise as a relevant intervention for Type 2 Diabetes (Colberg, et al. 2010; Marwick et al., 2009).

According to guidelines, exercise supervised by qualified professionals shows the greatest effect on glycaemic control. As American College of Sport Medicine and the American Diabetes Association guidelines (Colberg et al., 2010) stated:

Initial instruction and periodic supervision by a qualified exercise trainer is recommended for most persons with Type 2 Diabetes, particularly if they undertake resistance exercise training, to ensure optimal benefits to blood glucose control, blood pressure, lipids, and cardiovascular risk and to minimize injuries. (p. 156).

Balducci, Leonetti, Di Mario and Fallucca (2004) demonstrated that even low to moderate-intensity resistance training, combined with moderate aerobic exercise (three times a week) significantly improves metabolic and lipidic profiles, adiposity and blood pressure after a year. Moreover, the combination of resistance and aerobic training offers a synergistic and incremental effect on glycaemic control in people with Type 2 Diabetes (Zanuso, Jimenez, Pugliese, Corigliano and Balducci, 2010).

Psychological effects of exercise are well documented in people with Type 2 Diabetes. The aerobic training seems to have positive effect on anxiety, resistance training reduces symptoms of depression and mixed training seems to affect the quality of life (van der Heijden, van Dooren, Pop and Pouwer, 2013). However, despite the strong evidence of protective effects of exercise in T2DM, the majority of this population remains inactive and those who start an exercise program are not willing to train themselves in the long-term (Armstrong, 2015).

Therefore, current research is focusing on identifying the barriers to exercise programs in T2DM, as examples: "not having time", "health problems", "difficulty in controlling diabetes while exercising", "don't like to exercise", "no place to exercise", "exercise is boring", "lack of family support", and "not viewing exercise as important" (Erickson, 2013).

Interest is growing regarding self-efficacy, considered as beliefs about one's ability to successfully perform a specific behaviour such as physical activity (Bandura 1986). The influence of self-efficacy is considered to be strongest during the initial stages of an exercise program when the behaviour is novel; however, when behaviour becomes more habitual, its role diminishes. Also it is likely that the role of self-efficacy is fundamental when the organized exercise terminates and the individual is faced with the challenge of continuing to exercise regularly (McAuley, Jerome, Marquez, Elavsky and Blissmerr, 2003; McAuley, Courneya, Rudolph and Lox, 1994; Oman and King, 1998).

Cross-sectional studies that have investigated the role of self-efficacy in people with Type 2 Diabetes, have found a strong positive relationship between self-efficacy and exercise (Dutton et al., 2009; Guicciardi et al., 2014; Kirk, MacMillan and Webster, 2010). However, few longitudinal studies have investigated the role of self-efficacy as predictor or moderator of exercise behaviour in T2DM (Plotnikoff, Brez and Hotz, 2000; Plotnikoff, Lippke, Courneya, Birkett and Sigal, 2008; Plotnikoff, Lipkke, Johnson and Courneya, 2010), and to the best of our knowledge none examined the concurrent effect of exercise programs on self-efficacy.

Typically, the measures of efficacy employed reflect perceptions of capabilities for a single bout of activity rather than measures designed to predict exercise behaviour over prolonged periods of time or in the face of barriers to exercise participation. Indeed, it is quite possible that these latter types of self-efficacy will decline before the end of the program because participants have to re-evaluate their capabilities considering program termination (McAuley et al., 2003).

Several studies conducted with older adult participants in exercise intervention programs have not always shown improvements in self-efficacy (Hughes et al., 2004; McAuley et al., 2003; Moore et al., 2006). Particularly, McAuley et al. (2011) showed that exercise self-efficacy had a fluctuating trend. In the first three weeks of the randomized controlled trial, self-efficacy decreased due to the scarce experience of exercise, downsizing the effect of the initial overestimation. Then, because of a recalibration, its trend reverted and, at the end of the program, decreased again due to older adults' incapability of coping every-day with the challenge of continuing to practice without the support of an organized, structured, group-based activity. These results have important implications to boost intervention on self-efficacy in exercise programs targeted for inactive people or adults with chronic diseases.

In attempting to understand why exercise is so difficult to undertake and maintain, seldom have researchers considered the role of psychological stress although it is related to negative health behaviours (Lutz, Stults-Kolehmainen and Bartholomew, 2010).

There is no universal agreement on the definition of stress. McEwen (2007) simply stated: "Stress is a word used to describe experiences that are challenging emotionally and physiologically" (p. 874).

Lazarus and Folkman (1984) provided a transactional cognitive definition of stress related to appraisal, which indicates that individuals only perceive stress when a challenge or event is both threatening and of such a nature that the individual is unable to cope with it. In this viewpoint, objective demands and subjective appraisals may differentially affect health behaviours (Stults-Kolehmainen and Sinha, 2014).

The recent literature largely confirms the relationship between stress and exercise, showing that exercise contrasts the negative effects of psychological stress (Stults-Kolehmainen and Sinha, 2014).

Psychological stress is a ubiquitous condition in chronic diseases and exercise can be particularly relevant to buffer stress in vulnerable populations and individuals (Laugero, Falcon and Tucker, 2011). Moreover, psychological stress must be considered as a barrier to adopt and maintain exercise in T2DM patients, because its role is often overlooked (Holmes, Ekkekakis and Eisenmann, 2010).

Finally, it is often assumed that individuals in health-related interventions are drawn from a single population and have similar trajectories of change across these interventions. This assumption is the basis of a general linear model. However, a more realistic assumption may be that different sub-groups exist within intervention studies and that such groups display different trajectories of growth across time (McAuley et al., 2011).

While both the observed variables: self-efficacy and perceived stress are related to barriers to exercise, it can be hypothesized that they assume different growth trajectories, across individuals' ethnic and cultural groups, and populations. In a sample of older adults, McAuley et al. (2011) have identified two classes of individual patterns of self-efficacy by means of "mixed" models. The most frequent pattern shows an initial decline (baseline and 3 months), a later maintenance or increase (6 months) and a final decline (12 months); the less frequent pattern concerns individuals who had moderate exercise self-efficacy at baseline and did not experience a recalibration of their self-efficacy. Instead, these individuals experienced an increase in efficacy at both 3 weeks (baseline) and 6 months. Then, efficacy levels returned to slightly above baseline at 12 months. These results highlight the need for additional strategies to enhance efficacy beliefs at the end of the intervention (McAuley et al., 2011). To date, and to the authors' knowledge, the issues of different individual responses to exercise in T2DM patients have never been addressed in the literature.

Based on these premises, the aim of this longitudinal study is to investigate variations in selfefficacy and perceived stress as effects of supervised exercise training (6 months) in a small sample of the T2DM population at two levels: variation across time and variation between subjects. Particularly, it is hypothesized that: a) barriers at baseline are overestimated, therefore the measure of self-efficacy

decreases at the end of the program (6 month); b) at the end of the program (6 month) perceived stress decreases. Finally, the focus is on estimating individual differences in both variables.

Method

Study Design

One-group pre-post design was carried out in which all participants were involved in supervised exercise training. All participants agreed to sign a written informed consent.

Participants

A small sample of 23 participants with T2DM, recruited from the Centre for Diabetology, San Giovanni University Hospital, Cagliari (Italy), was enrolled in supervised exercise training (6 months).

In order to participate in the exercise program, individuals had to have diagnosis of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus for at least 2 years. Participants were screened for underlying ischaemic heart disease by performing a maximal exercise tolerance test on a motorized treadmill according to a standard Bruce Protocol (Bruce, 1971). The sample consisted of 12 males and 11 females, with a mean age of 60.22 ± 8.99 years and mean diabetes duration of 6.04 ± 5.67 years. Mean body mass index (BMI) at baseline was 30.79 ± 4.84 kg/m2 and at 6 months was 29.58 ± 4.88 kg/m2.

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus was defined according to criteria established by the American Diabetes Association (2014) as a progressive insulin secretory defect on the background of insulin resistance.

Diabetes Mellitus was controlled by the participants by diet (n = 5), oral hypoglycaemic agents (n = 11), insulin (n = 6), or a combination of oral hypoglycaemic agents and insulin (n = 1).

Measures

Demographic Characteristics. A brief questionnaire assessed basic demographic information, including gender, age, education, and marital status.

Self-efficacy was measured with the Exercise Self-Efficacy Scale (Marcus, Selby, Niaura and Rossi, 1992), which assesses an individual's confidence to participate in physical activity under five circumstances (e.g., "I am in a bad mood," "It is raining or snowing"). A continuum 0-100 was used, where 0 indicates being not at all confident and 100 being very confident. Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient at baseline for the overall scale in the present study was 0.80. The original English version had been translated into Italian previously and administered to a sample of three hundred eight persons with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (Guicciardi et al., 2014).

Stress was measured with the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (Cohen, Kamarck and Mermelstein, 1983), which is a 14-item self-reporting instrument used to provide a global measure of perceived stress in daily life. Responses range from "never" to "very often" on a 5-point scale. The PSS has adequate reliability and correlates well with life-events stress measures and social anxiety. Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient at baseline for the overall scale in the present study was 0.84. The original English version was translated into Italian prior to its administration to the sample, by Guicciardi and colleagues.

Procedures

Participants were screened for underlying ischaemic heart disease by performing a maximal exercise tolerance test on a motorized treadmill according to a standard Bruce Protocol (Bruce, 1971). All participants performed a 2 km UKK Walking Test. Seven days later, participants attended for visit two, and completed validated questionnaires. Participants were randomly divided into six sequential groups that participated in a supervised exercise program of aerobic activity and strength training once a week for 6 months. The training program was divided in two parts: the first (45 minutes) for instruction in "Fitwalking", the second (30 minutes) focused on improving strength and muscular endurance (stretching, balance exercises, etc.). At 6 months, all outcome measures carried out at baseline were repeated using the same procedures.

Data analysis

The effects of exercise training on psychological variables (self-efficacy and perceived stress) were analysed using mixed-effects models fitted by the package lme4 (Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker, 2015) for the R software (R Core Team, 2015). Two separate analyses for self-efficacy and perceived stress were conducted.

For each dependent variable, we considered the subjects as random factors and the time as fixed factors (two levels). To test the differences between the end and the beginning of the program, we compared the model including the fixed factor "time", against the "null" model, considering the intercept as single fixed parameter. The comparison was performed by using the likelihood ratio test (chi-squared statistics) and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1974). If the model including the fixed factor presents a smaller AIC than the null model, the "time" factor can be considered as a good predictor of the dependent variable. We expressed the difference in AIC between the two models as ΔAIC.

The individual differences were quantified using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC (1)), which provides an estimate of the effect of individual variability on the total variability.

Results

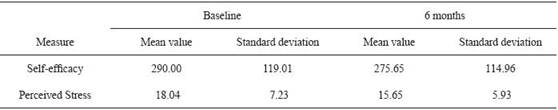

Table 1 details the descriptive statistics for the self-efficacy and perceived stress measures at each time point (baseline and at 6 months) for the total sample. Males and females did not differ on the self-efficacy and perceived stress measures.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics for Self-efficacy and Perceived Stress measures for the total sample

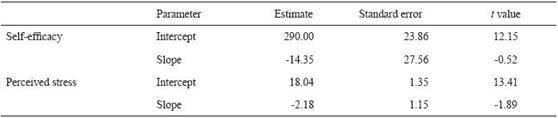

Parameters estimated for the models, which include the "time" predictor for each psychological variable, are reported in table 2.

Table 2: Results of analyses conducted through mixed-effects models on self-efficacy and perceived stress

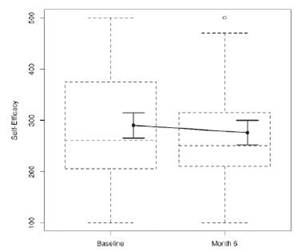

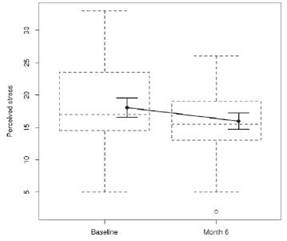

Self-efficacy: the results show that 35% of total variance can be explained by individual differences (ICC (1) = 0.35). The difference between the end and the beginning of the program was not noticeable: by adding the "time" factor (β = -14.35, t = -0.52) the null model does not improve (χ2 (1) = 0.27, p = 0.60, ΔAIC = 1.73), (Figure 1)

Perceived stress: the intra-class correlation coefficient shows that 61% of total variance can be explained by individual differences (ICC (1) = 0.61). According to the likelihood ratio test, the model which includes the "time" factor (β = -2.18, t = -1.89) is not different from the null model (χ2 (1) = 3.31, p = 0.07); however, the AIC is in favour of the model which includes the predictor, but with weak evidence (ΔAIC = -1.31), (Figure 2).

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first study that investigates over time and between subject variations of self-efficacy and perceived stress, as effects of supervised exercise training (6 months) in adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.

Our first hypothesis that measures of self-efficacy and perceived stress decrease at the end of the program (6 month) has not been supported. However, a general decline in the mean values of both variables, despite the absence of statistical significance, partially supports the previous literature (Hughes et al., 2004; McAuley et al., 2003; Moore et al., 2006). The reduction in the mean value of self-efficacy supports the findings reported by McAuley et al. (2011) that explain this decline with the need of older adults to recalibrate their self-efficacy upon being exposed to the exercise experience. Also, it highlights how participants re-evaluate their capabilities considering program termination. It is therefore important to examine how efficacy expectations change over the course of exercise interventions as well as to identify which factors are important sources for enhancing efficacy at the end of the program.

The reduction in mean value of perceived stress after participation in an exercise program supports the literature that shows that exercise contrasts the negative effects of psychological stress (Stults- Kolehmainen and Sinha, 2014).

These results confirm the importance of including stress management techniques at the beginning of an exercise program in order to reduce the possible impact of psychological stress as a barrier to the adoption and maintenance of exercise behaviour, in people with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.

Our exploratory analysis, which aims at determining the estimation of individual differences in self-efficacy and perceived stress in adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus participating in exercise training, has produced some intriguing findings.

Our results show that 35% and 61% of total variance can be explained by individual differences respectively in self-efficacy and perceived stress. Therefore, the absence of statistical significance in the variation across time in both variables considered might be explained by the high individual variability.

These results on individual variability are key to the development of customized exercise programs in T2DM.

Further analysis should be conducted to determine whether specific sub-groups of T2DM patients could be considered in relation to self-efficacy and perceived stress and the extent to which these groups demonstrate differential trajectories.

Despite our hypotheses not having been statistically confirmed, we believe that this longitudinal study is interesting for several aspects. The use of contemporary statistical methods to determine change across time and individual differences in T2DM adults had not been previously taken into account. We chose a mixed effects model because it can account for these two forms of variability; moreover, the accuracy of these models improves as the individual contributes more data, supporting our goal of developing evidence-based programs to promote exercise in T2DM.

Thus, it will be important for researchers designing future exercise intervention trials to make informed decisions on which measures are appropriate and which may be subject to recalibration, and to enact strategies in the early and later stages of the program to ensure realistic estimations of these important determinants of exercise behaviour.

We acknowledge that the study has some limitations. First, the small sample size limits the generalizability of the study findings. An additional limitation concerns our assessments of self-efficacy, perceived stress and exercise frequency, which were restricted to physical activity within the exercise program. Future studies should measure daily activity or compare less traditional approaches (i.e., lifestyle, non-structured programs) to an exercise intervention. Another limitation includes the possible discordance between self-reported and physiological responses to stress, such as cortisol and insulin levels.

Future studies should add non-invasive technological tools for measurement of physiological responses to stress.

Additionally, we acknowledge that the small sample size of our study would have required repeated measurements intermediate between the baseline and 6 months. Also, this particular study design did not incorporate a non-treatment control condition; therefore it would be prudent to assess self-efficacy and perceived stress in non-interventional groups in future trials to ensure accuracy of baseline measures.

In summary, we believe that the findings from this longitudinal study shed new light on how self-efficacy and perceived stress operate in adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Implementing the strategies of self-efficacy boosting and stress management in the different phases of exercise programs may help improve adherence to exercise in T2DM.