Introduction

With ca. 30,000 plant species, the South American tropical Andes is the world's richest plant biodiversity hotspot (Myers et al. 2000, Mittermeier et al. 2011, Ulloa et al. 2017, Antonelli 2021, Pérez-Escobar et al. in press). For centuries, this hyper-diversity of the region has attracted the interest of botanists (Cuatrecasas 1958), geologists (Hoorn et al. 2010), naturalists (Humboldt 1820, Darwin 1846), and all range of scientists (Gentry 1982, Antonelli et al. 2009, Antonelli & Sanmartín, 2011, Pérez-Escobar et al. 2017a, 2019), yet knowledge gaps remain in understanding plant species diversity, its origin, and distribution (Antonelli et al. 2018a). This lack of understanding stems from the scarcity of floristic studies and botanical exploration in the region (Orejuela 2005), an urgent task that is sorely needed because of the constant threat of climate change and anthropogenic pressures on Andean ecosystems (Pérez-Escobar et al. 2009, Parra-Sánchez et al. 2016, Helmer et al. 2019).

The Orchidaceae are one of the most prominent floristic elements of the tropical Andes (Gentry & Dodson 1987, Pérez-Escobar et al. 2017a, Pérez-Escobar et al. in press). In particular, the western slope of the western range in the Northern Andean cordillera of Colombia and Ecuador exhibits higher levels of orchid endemism (Gentry 1982, Zotz 2013) and richness (Gentry & Dodson 1987) when compared with the rest of the tropical Andes. This high epiphyte diversity is attributed to the confluence of Andean and Chocoan landscapes at the Andean foothills (Richter et al. 2009), the high humidity at mid-range elevations (Küper et al. 2004), and rapid orchid diversifications boosted by biotic and abiotic factors such as Andean mountain building (Givnish et al. 2015, Pérez-Escobar et al. 2017a, 2019), migrant exchanges between biogeographical regions (Pérez-Escobar et al. 2017b, 2019, Antonelli et al. 2018b) and the evolution of plant-organism interactions (Ramírez et al. 2011, Givnish et al. 2015, Balbuena et al. 2020).

Despite the biological importance of the ecosystems nested in the western slope of the Northern Andes' western range (Amaya-Marquez & Marín-Gómez 2012), only a few floristic studies aimed at quantifying its orchid diversity have been conducted (Silverstone-Sopkin & Ramos-Pérez 1995, Misas-Urreta 2005, García-Ramírez & García-Revelo 2013). To date, 160 orchid species (of which five are endemic) in 37 genera have been recorded for selected protected areas in the region, including Serranía de los Paraguas and Cerro del Torrá. As an outcome of field expeditions conducted in 2018 in the Serranía del Paraguas (western slope of the western range in Northern Andes, Colombia, between Valle del Cauca and Chocó departments) aimed at expanding our knowledge on the orchid diversity of this locality. Populations of two morphologically distinctive species from the genera Lepanthes Sw. and Camaridium Lindl. were discovered, which we propose here as new.

Lepanthes Sw. is one of the most species-rich groups in the Neotropics with >1200 species and the third most diverse in Colombia with about 304 species. Most of the diversity of Lepanthes is recent and derived from rapid diversifications in the Andes and Central America (Pérez-Escobar et al. 2017a). In addition, most of the species have narrow distributions, restricted to specific mountain ranges. For example, ~98% of the species of Costa Rica and Panama (mainly in the Cordillera de Talamanca) are endemic and do not occur in the Andes or northern Central America. In Colombia, Moreno et al. (2019) identified the western range of the Northern Andes as one of the ten hotspots for Lepanthes in the country. They pointed out the need for floristic studies in the region.

Camaridium comprises about 80 species ranging from southern Florida (USA) and Mexico to Peru and southeastern Brazil. Most of the diversity is concentrated in Costa Rica and Panama, with >80% of the species. There are 18 species in Colombia, but new species frequently appear with more botanical exploration and reliable herbarium identifications (Rodríguez-Martínez & Blanco 2015). Also, floristic similarities between southern Central America and Chocó suggest that the number of species discovered within the Maxillarinae in the Northern Andes' western range of Colombia could increase (Kirby 2011, Pérez-Escobar et al. 2019).

Materials and methods

We collected living plants in field in March 2018 at Valle del Cauca, El Cairo municipality, Colombia. The descriptions and drawings were based on living specimens and herbarium material, following the terminology by Christenson (2013) and Luer (2011). Digital images were taken with a Nikon D7100 with a Nikon AF-D 50 mm f/1.8 lens. Sketches were prepared with a Leica® MZ7.5 stereomicroscope with a drawing tube and digitalized. A draft composite template was designed in Adobe Photoshop® CS6 and exported as a JPEG file. Then, we made the digital composite-line drawing (lines and stippling), uploading the template in Procreate illustration applications for iPad Pro tablet computer (Apple Inc.). The resulting drawing was exported as TIFF file at 800 dpi. The Camaridium species was prepared and inked in paper.

Taxonomic treatment

Camaridium antonellii O.Pérez & Bogarín, sp. nov.

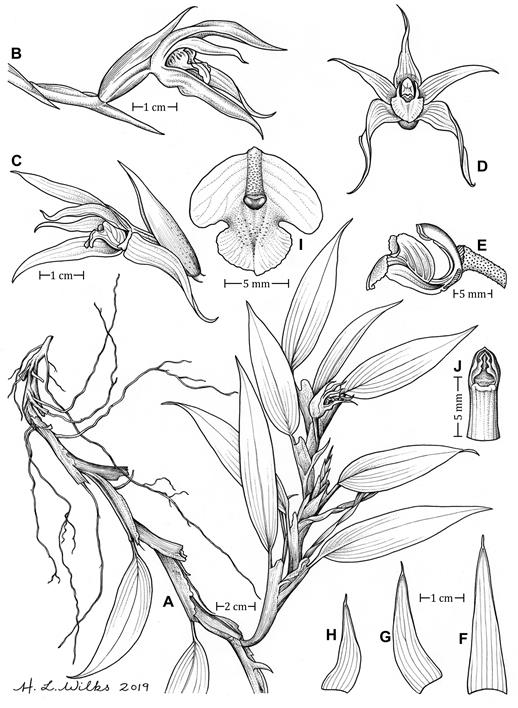

TYPE: Colombia. Valle del Cauca: El Cairo municipality, Cerro El Inglés, ''Santicos'' locality, epiphyte in disturbed forest, 2330 m, 25 March 2018, O. Pérez-Escobar & A. Zuluaga 1987 (Holotype: CUVC). Fig. 1-2.

Diagnosis: Camaridium antonellii is similar to the Central American C. inauditum (Rchb.f.) M.A.Blanco, but differs in the fractiflex leaf-sheaths, ovate-elliptic, acute leaves, the flowers with dark pink to purple sepals and petals, the distinctly three-lobed lip, white, spotted with purple on the lateral lobes and yellow-cream towards the apex, the mid-lobe ovate to transverse ovate, and lanceolate sepals.

A. Habit.

B. Flower in lateral position.

C Flower in lateral position, exposing the lip.

D. Flower in frontal position.

E. Ovary, column and lip, lateral view.

F-G. Dorsal, lateral sepal and petal in ventral position, respectively.

I. Lip (ventral position).

J. Column (ventral position).

Drawn from the holotype by H. Wilks.

Figure 1 Camaridium antonellii.

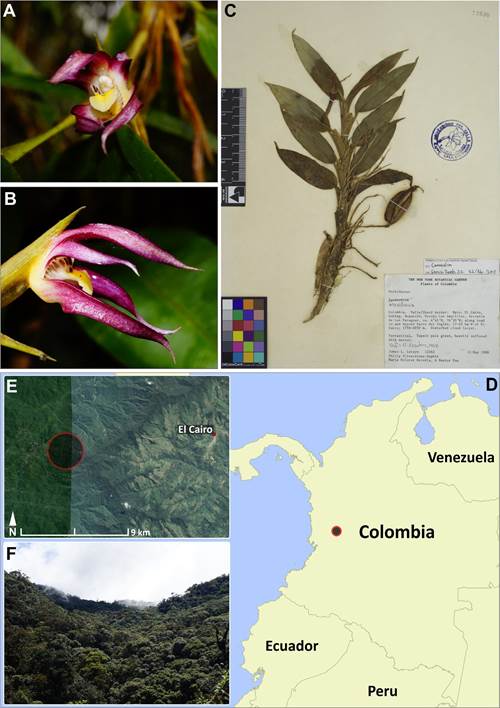

Photos: O. Pérez & Google Earth.

Figure 2. A-B. Flowers of Camaridium antonellii in Frontal and lateral position, respectively. C Pressed plant of C. antonellii bearing a dehiscent fruit (Luteyn 12262 CUVC!). D-E. Type locality of C. antonellii and Lepanthes valerieae (enclosed in the black circle). F. Canopy view of cloud forests in Serrania del Paraguas (type locality).

Plant epiphyte, up to 44 cm tall. Roots white, 1 mm thick, lateral, profuse, produced from the base of the leaves and sprouting from the leaf sheaths. Stems sympodial canes, decumbent, flattened, with fractiflex leaf-sheaths, rarely branching towards the apex, without evident pseudobulbs. 22-26 cm long, 0.8-1.5 cm wide, entirely covered by the leaf sheaths. Leaves distichous, 5-11, monomorphic, the blade ovate-elliptic, coriaceous, deciduous, green, acute, minutely mucronate, the base invaginate, with a clear abscission line, pseudopetiolate, 7-12 × 2 cm; the petiole conduplicate and articulated with the leaf, coriaceous, cordate, winged, persistent on the stem after leaf's abscission. Inflorescences single-flowered, produced from the apical leaf sheath's axils, 1-many per axil, with flowers opening successively. Peduncle 16 mm long, with 2-4 distichous, conduplicate, acute, yellow-green pale, papyraceous bracts (including the floral bract), slightly verrucous towards the apex, the papillae pale brown, 31.1-32.2 × 12 mm, the floral bract extending over basal 1/3 of the dorsal sepal with the midrib stained with purple. Ovary pedicellate, 14 mm long (including the pedicel), markedly verrucose in the distal half. Flowers resupinate; sepals and petals pink towards the distal two thirds, the margin slightly darker, the base white to pale yellow, immaculate; lip white with transverse purple blotches on the lateral lobes extending to the margins, pale yellow towards the apex, with a yellow callus; column white. Sepals narrowly triangular to lanceolate, acute, mucronate, fleshy; the dorsal sepal 36.7 × 9.0 mm, 7-veined, the lateral sepals falcate, 30.4 × 7.6 mm, 7-veined. Petals lanceolate, falcate, acute, mucronate, 22.2 × 7.1 cm, 6-veined. Lip sub-rhombic, three-lobed, slightly truncate at the base, with a prominent oblong, apically projected bifid callus extending from the base of the lip to the apical portion of the disc, 10.1 × 10.3 mm; lateral lobes obliquely elliptic, obtuse, erect, entire, 6.1× 4.0 mm; mid-lobe broadly ovate to transverse ovate, subtruncate, obtuse with a small mucron, margin sub-crenate, fleshy, 5.0 × 5.9 mm. Column arcuate, hemicylindrical, 7.8 × 2.8mm. Anther apical, stigma ventral. Pollinia not seen. Fruit oblong, 47 mm long.

Eponymy

This new species honours Prof. Alexandre Antonelli, Director of Science at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (UK) and mentor of the lead authors of this paper. Prof. Antonelli is one of the most prominent tropical plant biogeographers of the 21st century, whose contributions have revolutionized the understanding of the spatio-temporal dynamics of plant diversification in the American tropics, including orchids.

Habitat and ecology

Epiphyte, growing in primary forest, humid tropical forest (cloud forest), at 1700-2300 m elevation. Dense populations of C. antonellii of 15 or more individuals were reported growing on isolated trees. Camaridium antonelli is the only known representative of the genus growing in the type locality.

Distribution

Endemic to the Chocó, Colombia, where it is only known from the type locality (Fig. 2D, E).

Discussion

Camaridium antonellii is similar to the Central American C. inauditum but differs in the fractiflex leaf-sheaths, ovate-elliptic, acute leaves (vs. two-ranked, oblong, obtuse), the flowers with pink sepals and petals (vs. ivory white), the distinctly three-lobed lip (vs. obscurely three-lobed), white, spotted with purple on the lateral lobes and yellow-cream towards the apex (vs. yellow and also light stained with brownish to the apex), the mid-lobe broadly ovate to transverse ovate (vs. ovate to elliptical), and the lanceolate sepals (vs. linear).

Some species of Camaridium and Maxillaria Ruiz & Pav., as defined by Whitten et al. (2007)but its current generic boundaries and relationships have long been regarded as artificial. Phylogenetic relationships within subtribe Maxillariinae sensu Dressler (1993, can be confused mostly because of the generalized plant habit. However, plants of Camaridium typically lack pseudobulbs in contrast to Maxillaria s.s., which shows well-developed pseudobulbs with one apical, spatulate leaf. Nevertheless, some of these traits evolved several times across the Maxillariinae (in Ornithidium Salisb. ex R.Br., Maxillaria s.s., and the M. variabilis clades), their taxonomic value in generic delimitations is not useful. Therefore, Whitten et al. (2007)but its current generic boundaries and relationships have long been regarded as artificial. Phylogenetic relationships within subtribe Maxillariinae sensu Dressler (1993 suggested the combination of apical fruit dehiscence, absence of fibers in floral segments, and a floral bract that often exceeds the ovary to separate Camaridium from Maxillaria. Vegetatively, some species of Maxillaria s.s., such as Maxillaria caveroi D.E.Benn. & Christenson, M. floribunda Lindl., M. platyloba Schltr. and M. sibundoyensis Szlach., Kolan., Lipińska & Medina Tr. (Bennett & Christenson 1998, Bentham 1839, Schlechter 1921, Szlachetko et al. 2017) are similar to C. antonellii, mainly in plant habit and general flower appearance. However, plants of these species have traits typical of Maxillaria s.s. such as the tough perianth fibers, crested or ornamented anther cap (Blanco et al. 2007). If the broad generic concept of Maxillaria proposed by Schuiteman & Chase (2015) is accepted, then C. antonellii also differs from the species of the M. platyloba group (Christenson 2013) mainly by the pink sepals and petals, yellow-cream lip (vs. yellow or brown sepals and petals), lanceolate dorsal sepal (vs. linear, oblong) and the ovate to transverse ovate, acute lip (vs. ovate to elliptical, truncate, emarginate or obtuse).

Lepanthes valerieae O.Pérez, Jaramillo & Bogarín, sp. nov.

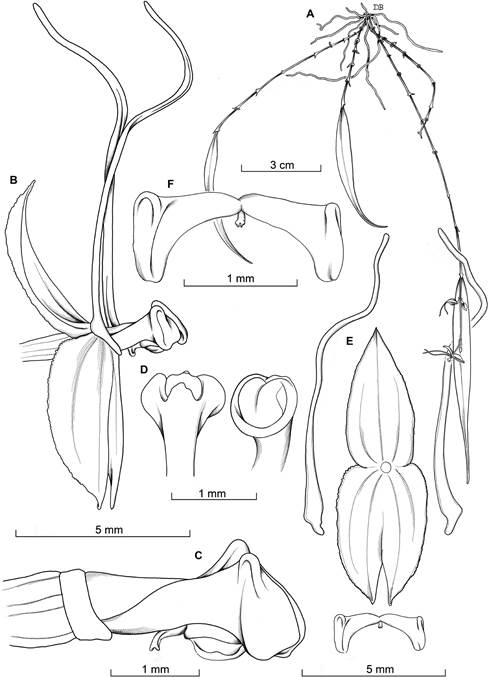

TYPE: Colombia.Valle del Cauca, El Cairo municipality, Cerro El Inglés, 2300 m, 25 March 2018, O.A. Pérez et al. 1981 (holotype: CUVC). Fig. 3-4.

Diagnosis: Lepanthes valerieae is most similar to L. silverstonei Luer, but it differs in the narrowly-elliptic to narrowly ovate leaves, < 1 cm wide, the filiform upper lobe of the petals surpassing the dorsal sepal length and the rudimentary ovate, sub-triangular lower lobe, and the triangular, concave appendix with a subcylindric, retuse almost glabrous apex. It is also similar to L. antennata Luer & Escobar; however, it is distinguished by the long apical lobes of petals, surpassing the dorsal sepal, the longer connectives > 18 mm, rounded lobes of the lip, and the oblong, flattened appendix.

Plant epiphytic, pendent, or suberect, up to 20 cm tall. Roots slender, flexuous, to 1 mm in diameter. Ramicauls slender, suberect, when young, mostly pendent at maturity, to 12 cm long, enclosed by 6-11 brownish, adpressed lepanthiform sheaths, the ostia minutely ciliate, acute. Leaves narrowly-elliptic to narrowly lanceolate, coriaceous, attenuate-acuminate, with recurved margins, 8.0 × 1.0 cm, the attenuate base narrowing into a petiole less than 3 mm long. Inflorescence racemose, distichous, glabrous, successively flowered, developed above the leaf, shorter than the leaves, up to 3.0 cm, long, peduncle 2.5 mm long, rachis 5 mm long. Floral bracts ovate, acuminate, 1 mm long. Pedicels 2 mm long, persistent. Ovary to 3 mm long, glabrous. Flowers with red sepals, the dorsal sepal yellowish tinted red, the lateral sepals with a yellow mid-vein, and light-yellow petals basally tinted red with reddish tips and yellow lip and column. Dorsal sepal, ovate, acute, concave, denticulate, abaxially with three ciliate keels, connate to the lateral sepals for about 1 mm, 4.8 × 2.5 mm. Lateral sepals oblong-ovate, acute, denticulate, abaxially with two ciliate keels, oblique, connate for about 3 mm, 5.0 ×3.2 mm. Petals transversally bilobed, minutely ciliate, 0.8 × 11.4 mm, the upper lobe filiform ovate at the base, filiform, 10.8 × 0.8 mm, the lower lobe introrse, ovate, sub-triangular, about 0.5 mm long. Lip bilobed, minutely pubescent, adnate to the column at the base, exceeding the column length, with oblong blades and rounded ends, embracing the column, 1.5 × 3.2 mm, with cylindrical connectives, 1.8 mm long, the narrow body, laminar, connate to the base of the column, appendix triangular, concave, with a subcylindric retuse, almost glabrous apex. Column cylindrical to 2.2 mm long, with a prominent, orbicular stigma with the margins papillose, anther apical, and stigma ventral. Pollinia two, obovoid. Anther cap, cucullate. Fruit not seen.

Eponymy

This species honors Valerie Anders for her passion for supporting science projects that celebrate the Anders' family legacy of exploring and expanding human knowledge. Her generosity has helped generations of paleobiologists worldwide, especially Latin America, that seek to understand the evolution of life and landscapes in the Tropics.

Phenology

Flowering was recorded in March and April.

A. Habit.

B. Flower in natural position.

C. Ovary, column and lip, lateral view.

D. Column.

E. Dissected perianth, flattened.

F. Lip spread, adaxial view.

Drawn from the holotype by D. Bogarín.

Figure 3 Lepanthes valerieae.

Habitat and ecology

Epiphyte, growing in primary humid tropical (cloud) forest on branches and twigs in the forest floor at 1700 m elevation. Two populations growing in bushes and distanced each other by about five meters were further reported. The type locality seems to be highly diverse in Lepanthes orchids. Here, at least ten different species (including L. antennata) were recorded in adjacent branches.

Discussion

Lepanthes valerieae is also most similar to L. silverstonei, but it differs in the narrowly-elliptic to narrowly ovate leaves, < 1 cm wide (vs. ovate, > 2 cm wide), the filiform upper lobe of the petals surpassing the dorsal sepal length (vs. anguste-linear, shorter than the dorsal sepal) and the rudimentary ovate, sub-triangular lower lobe (vs. anguste-triangular, falcate) and the triangular, concave appendix with a subcylindric, retuse almost glabrous apex (vs. convex, with a pubescent, flabellate apex). Lepanthes valerieae also resembles L. antennata mostly in its filiform, long upper lobes of the lip; however, it is distinguished by the long apical lobes of petals, surpassing the dorsal sepal (vs. shorter or as long as the dorsal sepal), the longer connectives > 18 mm (vs. <1 mm long), rounded lobes of the lip and the oblong, flattened appendix (vs. triangular, concave).

Morphological variation in Lepanthes silverstonei has been documented in several other localities near the locus typus (Sebastian Vieira, pers. com. November 2020). Apparently, the petals of that species vary from filiform to bifid and shorter to more prolonged than the sepals. In addition, the phylogenetic relationships of L. valerieae with other morphologically similar species, including L. antennata and L. licrophora Luer & B.T.Larsen, remains to be tested. Thus, the description of L. valerieae, in addition to L. antennata, L. licrophora, and L. silverstonei (and its possible variations), provides new morphometrical resources to test hypothesis on Lepanthes species complexes (Bogarín et al. 2018). Such data, in cobinaiton with different lines of evidence such as DNA sequences will further enable the conduction of future integrated monographic work in the genus (Grace et al. 2021) but also comparative studies focusing on generic delimitations in the lineage and Pleurothallidinae overall (Bogarín et al. 2019). Also, given the intricate vegetative and reproductive morphology (Luer 2011, Bogarín et al. 2018) and rapid speciations characteristic of the genus (Pérez-Escobar et al. 2017a), phylogenomic (Bogarín et al. 2018, Pérez-Escobar et al. 2020, Peakall et al. 2021, Pérez-Escobar et al. 2021, Serna-Sánchez et al. 2021) and statistical morphometric approaches (Bateman et al. 2018, 2021) are needed to sort such species complexes.

uBio

uBio