-

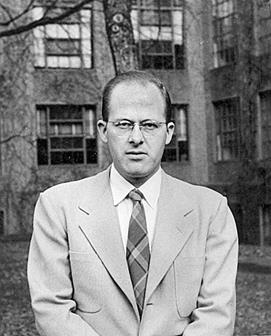

In april of 2005, in the journal Epidendrum (one of the journals of Lankester botanical Garden at that time), a small article was published, which I co-authored with Jorge Warner, then Director of the garden, under the title “Bienvenidos, Dresslers”. Dr. Robert Louis Dressler (1927-2019), who is at this moment waiting peacefully for us on the other side of the river, had arrived in Costa Rica on March 11 of that year, to take over the position of Scientific Coordinator of the research staff of the garden. Ten years later, in 2015, Franco Pupulin, who was instrumental in bringing Dr. Dressler to the university of Costa Rica, called this perhaps the most transcendental moment in the life of our botanical garden.

And Franco continued: from the point of view of our institution, the name of Dressler as a faculty member simply put us into the game. But from the point of view of the people who, like me, had the luck to learn, day by day, Bob’s ideas and hypotheses, who had the fortune to go with him to the field as the best of the mates, to share with him endless talks and discussions about orchids and science, and men and life, to see him beginning his work early in the morning with willfulness, the inevitable cup of coffee and a smile, taking notes by hand of his daily observations in the little space left amid books and journals and notes in the middle of the less than perfect order of his office, to appreciate his simple and humble attitude in science and in friendship, it was an immense fortune to have him as the greatest of all possible companions.

With Dressler on its staff, Lankester Botanical Garden became not only one of the most important centers on orchid research in our continente, but also a point of attraction to foreign botanists who would not miss the opportunity to discuss their projects with Dressler, and to accompany him on one of his numerous field trips. it is for me difficult to avoid the comparison and not to remember the words of Louis O. Williams, in his obituary for Charles H. Lankester in 1972: Generous to a fault, hospitable to all, he was counselor to all scientists who came to Costa Rica.

I am fortunate to have experienced his generosity from the first day I made contact with him. It must have been around 1997 -Dressler was living at that time in Florida- when I wrote to him asking for permission to use an illustration published in one of his articles. His reply came immediately: You don’ need my permission, feel free to use anything that I have ever published. Later, when I finally met him in person, he opened to me the few boxes with books and papers that he had brought with him from Florida, and let me make copies of documents which I will always cherish as witnesses of Dressler’s long engagement with orchids, among them his correspondence with Ruth Oberg and Ed Greenwood in Mexico, and with Rafael Lucas Rodriguez in Costa Rica.

Robert Louis Dressler was born on June 2, 1927, and raised during the Great Depression in rural Taney County, Missouri. Taney County is in the Ozark Mountains, a fiercely independent but poor people. His father, Mryl, was an electrician who farmed 30 acres of rocky ground to put food on the table. While cutting wood in 1937, Myrl’s electric saw kicked back and cut his arm, and he died four days later of a pulmonary embolism. So at the age of ten Bob (as he liked to be called) became the man of the family and helped to take care of his two younger sisters and mother. The family later moved to Inglewood, California, where his mother worked as a stenographer for an insurance company.

Bob developed a love of nature at an early age, handling snakes, asses, and old goats, which would give him valuable experience later in his professional life. He graduated from Gardena High School in Los Angeles, California, in 1945 and the following year served as a finance clerk in the U.S. Army. After that he attended the University of Southern California, where he was a member of Phi Beta Kappa Honor Society. He received his Bachelor of Arts degree in botany (cum laude) in 1951. Following that he went east to Harvard and received his Ph.D. in biology in 1957 with a dissertation on the genus Pedilanthus (Euphorbiaceae). His major professor was Reed Rollins, who co-founded the International Association of Plant Taxonomy and also the Organization for Tropical Studies.

From 1958 to 1963 he returned to his Missouri roots and used his systematics skills as editor of the Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden while he was also assistant Professor at Washington university (1961- 1963) in St. Louis. His first taste of the Neotropics began in 1961 when he was hired on the staff of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Panama, a position he held until 1990.

One of Bob’s frequent companions in the field was Calaway Dodson, then professor at the University of Miami. Bob and Cal collaborated on numerous projects over the years. On a collecting trip to Panama in 1963, they met Martin Moynihan, who was a primate specialist and resident naturalist for the Smithsonian Institution’s Tropical Field Station there. Moynihan mentioned he was looking for staff scientists, so Bob rushed to apply and was hired that same year at what would become known as the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

Norris Williams first met Bob in Panama in 1965 while taking Owen Sexton’s course in tropical ecology from Washington University. He became interested in the euglossine bees visiting orchid flowers and asked where he could learn more about them. Bob recommended Cal Dodson, but Cal was in Peru that year on a Fulbright scholarship, so Norris finished a master’s degree at the University of Alabama, then applied for a predoctoral internship with Bob at STRI in Panama. He was the first of a host of students who moved into Bob’s office, left for their doctorates and then returned with their own students. after completing his PhD, Norris would bring groups of students on field trips, and Bob would take them all over Panama. Among them were Jim Ackerman, John Atwood, Jim Folsom, Mark Whitten and Alec Pridgeon, all of whom went on to develop their own academic careers in orchids.

His wife Kerry aptly characterized Bob as like a spider at the center of his web while he worked at STRI. Sooner or later field biologists of all specialities and many nations would visit Panama to work with him, and they would all benefit from his field trips and knowledge.

Alec Pridgeon recalls: I was one of those biologists, working on my Master of Science degree at Louisiana State University. Searching for a suitable topic for a master’s thesis on orchids, I wrote to Bob at STRI in 1976 for ideas. He quickly responded that he suspected that the four species of Bothriochilus Lem. were closely related to the monospecific Coelia Lindl., separated only by the length of the spur, and perhaps ought to be combined. With specimens of the two genera supplied by Eric Hágsater of the Asociacíon Mexicana de Orquideología, I then used chromosome counts, flavonoid chemistry analyses, scanning electron microscopy of pollinia, and studies in leaf anatomy to determine relationships. Three species of the two genera are virtually identical in all these aspects. On that basis Bothriochilus was moved to synonymy of Coelia, the earlier name. Nuclear and plastid DNA analyses by Cassio van den Berg 23 years later supported the monophyly of Coelia sensu lato. Bob had a gift for looking past phenotypic plasticity resulting from pollinator pressures and visualizing true genetic relationships. And he was happy to share that knowledge with a lowly master’s student.

During all these years Robert Dressler travelled incesantly through South and Central America, as well as to Mexico, where he enjoyed the hospitality of Eric Hágsater, whom he had met in Medellín, Colombia, in 1972. Eric recalls: In the following 30 years or so, I would have the opportunity to travel with Bob into the field not only to many corners of Mexico, but also to Guatemala, to Panama, where Bob and Kerry lived, as well as to Costa Rica and Colombia on several occasions, often taking advantage of invitations to national orchid expositions and conferences.

Bob was present at the inauguration of the new home of the Herbario AMO in Mexico City in January, 2002, where all Mexican orchid students gathered, both professionals and amateurs alike. It was Bob’s style of guidance and open mind to share his knowledge and work with younger generations, with care in studying and annotating as much material as possible, and his extensive field experience set the basis for the style of the team work at the AMO herbarium that has subsisted until today.

In 2015, the Instituto de Biología of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, the Asociación Mexicana de Orquideología, and the AMO Herbarium, joined to present a certificate of recognition to Robert Dressler for over four decades of support and sharing of his knowledge and friendship with the Mexican and world orchid community.

Kerry Radcliffe had worked as assistant to Dressler in the early 1970s, specializing in photography, and beginning a collection wich amounts presently around 25,000 pictures. In those years, Bob and Kerry spent a good deal of time in the field. One thing led inevitably to the other, and in 1977, they were married on his 50 birthday, June 2, 1977, at Marie Selby botanical Gardens with Carl and Jane Luer as best Man and Matron of Honor.

In 1984 Dora Emilia Mora de Retana, the Director of the Lankester Botanical Gardens in Cartago, Costa Rica, asked Bob to come up from Panamá and present a short course on classification of the orchids at the Universidad de Costa Rica in San Jose. Bob and Kerry had been regular visitors to Costa Rica, collecting and collaborating with Costa Rican botanists like Rafael Lucas Rodriguez since Bob began working there in the early 1960s. He often attended local orchid shows as a guest judge and Dora Emilia had heard a presentation he had given and was excited at the prospect of him teaching a full semester in Costa Rica.

Bob spent one half of a sabbatical year in Costa Rica with his family and collected and photographed many Costa Rican species. The local orchid societies were always ready for a field trip and between those and his official course trips he covered much of the country. The idea of a field guide to the two countries he knew so well was already taking form and after retiring from Stri would lead to his book: Field Guide to the Orchids of Costa Rica and Panama, published by Cornell University Press in 1993.

Everywhere Dressler went he incorporated his findings into what became his first major book on the classification of the orchids. Many of the photographs taken on these trips were used in the volume which was printed and released by Harvard University Press in 1981, The Orchids, Natural History and Classification which has become a classic in orchid literature. Pridgeon commented on Dressler’s work: Today, after 20 years of extensive DNA sequencing around the world and discovery of a handful of true orchid fossils, we have a much firmer grasp of orchid relationships and evolution and now classify Orchidaceae into five subfamilies: Apostasioideae, Vanilloideae, Cypripedioideae, Orchidoideae and Epidendroideae. But it was Dressler’s work in laying the foundation that now allows us to revel in all that we have learned in the last two decades.

In his later years Bob was Courtesy Curator of the Florida Museum of Natural History, associate of the Harvard University Herbaria, Senior Scientist at the Marie Selby botanical Gardens, and Curator of the Missouri Botanical Garden, until he finally moved to Costa Rica in 2005.

Many other well-known botanists and orchid experts have expressed their opinión about Robert Dressler. at this point, let us have them come to word. Norris Williams (Florida Museum of Natural History): Bob Dressler is the best field botanist and field companion I have ever met. I have known him since 1965 when he inspired me to work with orchids, and I have never regretted it. He is generous with his time and knowledge, has a great sense of humor and is a true orchidophile. His books are great. I think the most important thing I can say about him is he is receptive to all new ideas, even if they contradict some of his earlier ideas. A truly inspiring botanist, a great friend and a wonderful person.

Jim Ackermann (University of Puerto Rico): I try to emulate Bob’s approach to science with, I admit, varied success. Knowledge is fluid, fed by ideas, data and interpretation. All these change with time, and it is our task to evaluate new information on its merits and incorporate them in one’s own world. And when new knowledge contradicts our own ideas, then we need to drop the ego, evaluate and incorporate when appropriate. Bob’s classification systems were the best available for their times, and as new techniques and philosophical approaches suggested some alternative interpretations, Bob could have taken a defensive stance but instead embraced the brave new world.

Raymond Tremblay (University of Puerto Rico): Dr. Dressler’s The Orchids: Natural History and Classification was a career inspiring book that guided my interest in biology and ultimately in trying to understand evolutionary processes in plants. I’m also grateful for his kind words and comments as a reviewer of my first submitted manuscript; his recommendations and encouragement increased my enthusiasm to continue publishing.

Ken Cameron (university of Wisconsin, Madison): It is fair to say that two books changed my life and pushed me forward into orchidology. the first was the Golden Guide to Orchids that I discovered around age eight. The second was Bob Dressler’s The Orchids: Natural History and Classification, which I discovered a decade later in college as I considered a major in biology. His humility, scientific curiosity and encouragement of students was evident to me back in the 1990s when Mark Chase and I started using DNA data to understand evolutionary relationships among orchids. Bob’s classification system was the hypothesis we were testing, and when patterns of relationships began showing up that challenged the Dressler system he was not defensive or ofended by these. Quite the contrary - he was excited by our results and encouraged us to keep going.

With Friends in Colombia, 2015. Front row: Alec Pridgeon, Eric Hagsater, Franco Pupulin, Bob, Norris Williams. back row: Ken Cameron, Raymond Tremblay, James Ackerman.

To continue and finish with Pupulin’s memories of Dressler: In the last ten years, we had in him a model of honesty, of happiness and unselfish generosity. We learned from him that study is a matter of love. Dr. Robert Louis Dressler taught us how to become better observers, better botanists, better scientists and professors. And he showed us, in his characteristic and straight way, how to be better people.

Today, six academic generations of orchid researchers owe their careers in large part to Bob Dressler’s imposing productivity and willingness to collaborate and share his vast knowledge. His hearty chuckle and modest demeanor invited approach by anyone who might otherwise be reticent to ask a question of such an extraordinarily brilliant scientist. Bob showed mastery of the Neotropical flora and fauna, but he has also shown all of us that nature and its preservation should be our highest priorities. as those who knew him will attest, he was clearly a biologist for all seasons, one who will live on in his respected publications and in our hearts.

uBio

uBio