Introduction

Latin America is one of the regions in the world with the most water resources. However, its distribution in space and time causes water scarcity in extensive zones of the continent such as Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, and Peru (CEPAL, 2007.)

This situation becomes even worse with the convergence of other elements such as population distribution, pollution of water resources, and the growing demand for water by all consuming sectors. As a result, all countries are facing the unavoidable challenge of planning for managing this valuable natural resource in an efficient and effective manner. The region is facing constant challenges in the management of water resources, resulting in a need to find national-level legal and institutional formulas that may contribute to prevent and solve the growing conflicts caused by water use, as well as the crises generated by extreme natural phenomena, such as droughts or hurricanes (Dourojeanni & Jouravlev, 2001, García, 1998.)

While conflicts related to use of water resources increase, it seems that the capacity to solve them has been reduced in some countries in the region, due, among other reasons, to rapid changes in socio-economic and political contexts and the growing demand for water. Confronted with this different and complex scenario, it is difficult to improve management systems, especially given a lack of positive experiences for designing strategies to promote a planning model for water resources.

This article addresses the issue of planning and management of water resources in Latin America and the Caribbean, with the following objectives:

General objective:

Analyze the scenario of the current state and planning of water resources in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Specific objectives:

Summarize current supply (or availability) and use of water resources at country level.

Describe the regional context with respect to planning and management of water resources, with special emphasis in Central America.

Consider in depth the positive aspects of a successful case of planning and management of water resources in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Methodology

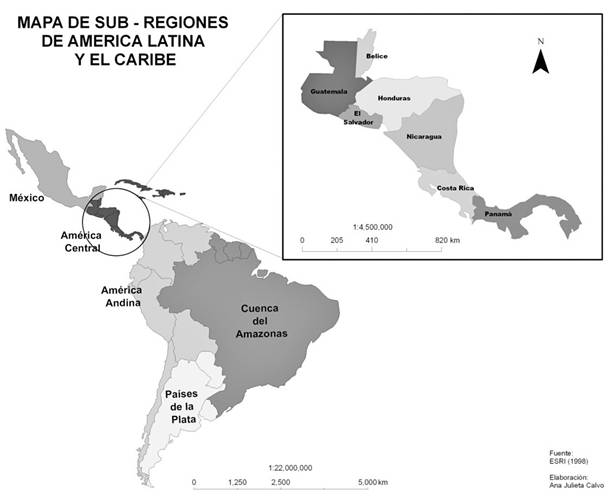

Recent reports and publications related to the subject of water resources in Latin America and the Caribbean were consulted for the present study, in particular those concerning planning and management of water resources, such as Ballestero et al. 2005, Jouravlev 2001, Dourojeanni 2000, CONAGUA 2006, and Valencia, Díaz and Ibarrola 2004. Based on these sources, the current state and context of planning of water resources is described in general terms, by previously defined regions (Fig 1.) Progress made so far is also discussed, taking as a reference the concept of “water resource planning”, and at least one of the cases from countries with the best achievements is selected.

Results and discussion

The Latin American and Caribbean context for planning of water resources

Availability of water resources in the region

Overall, Latin American and Caribbean countries have abundant water resources within an area that occupies only 15% of the planet’s surface. This area captures almost 30% of rainfall, and generates 33% of global runoff. Taking into account that the region has less than 10% of the world’s population, a figure of water supply per inhabitant amounting to 28,000 m3/inhab/year on average is obtained -well above the world average of 8,000 m3/ inhab /year, the average for Africa of 6,000 m3/ inhab /year, the average for Europe of 4,000 m3/ inhab /year, and that of Asia of 4,000 m3/ inhab /year (FAO, 2000, Ávila, 2002.)

The region ranges from humid to wet, with extreme variations in geographic and temporal availability within a single country, and between countries and regions. For instance, in Mexico, four large basins cover 10% of the country, and they capture 50% of the annual average volume flow. Meanwhile, three river basins in South America (Orinoco, Amazonas and del Plata) have about two-thirds of the annual average run-off of the entire region. Almost 25% of the land in Latin America and the Caribbean (about 5 million km2) corresponds to arid and semi-arid regions as a result of an irregular distribution of rainfall (Aldama & Gómez, 1996.) These regions are mainly in North and Central Mexico, the Northeast of Brazil, Argentina, and from Peru’s Pacific coast to the North of Chile (the Atacama Desert in Chile has been ranked as the driest place in the world.) There are also smaller dry zones in the Dominican Republic and in Northern Central America (García, 1998.)

Distribution of water resources within subregions shows cases of scarcity, which usually coincide with the most populated areas of the region. This is the case of Chile’s Central Valley, the Cuyo and Southern regions of Argentina, the Peruvian Coast and the Southern Equatorial Coast, the Valleys of Cauca and Magdalena in Colombia, the Bolivian Plateau, the Gran Chaco (shared by Bolivia, Argentina and Paraguay), the Brazilian North-east, the Pacific Coast of Central America, and a good part of Mexico.

Table 1 shows the distribution of water resources in extensive subregions. Some figures that are close to the generally used scarcity parameter (2.000 m3/inhab /year) are evident, as in the case of the Greater Antilles (FAO, 2000.)

Planning and management of water resources in Latin America and the Caribbean

Just as there is diversity in distribution of water resources in Latin American and Caribbean countries, there is also a great variety of approaches for their planning and management. In some countries, such as Mexico and Brazil, laws have been recently approved and their implementation is underway, including the creation of institutions such as the National Water Agency of Brazil, or the massive creation of River Basin Councils in Mexico; other countries have been discussing water laws for years, and some of them have gotten lost in environmental issues and institutional conflicts, as is the case with Costa Rica (Dourojeanni, 2000, Astorga, 2009.)

With this scenario, it is difficult to envision clear models for planning water resources in the region. However, there are experiences in countries where more progress has been made in addressing this issue. Annex 1 summarizes the most outstanding features of the legal and administrative context of water resources in some countries, and for all Latin American regions.

Table 1 Regional distribution of Internal Renewable Water Resources (IRWR)

| Subregion | Annual rainfall | Internal Renewable Water Resources | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mm | km³ | km³ | m³ per inhabitant (1997) | ||

| Mexico | 772 | 1512 | 409 | 4338 | |

| Central America Guatemala Honduras El Salvador Nicaragua Costa Rica Panama | 2395 2200 1880 1180 1000-4000 3300 3000 | 1194 | 6889 | 20370 8857 13776 2755 34672 27967 49262 | |

| Greater Antilles | 1451 | 288 | 82 | 2804 | |

| Lesser Antilles | 1141 | 17 | 4 | - | |

| Guyanese Subregion | 1421 | 897 | 329 | 191422 | |

| Andean Subregion | 1991 | 9394 | 5186 | 49902 | |

| Brazilian Subregion Amazon Basin | 1758 | 15026 | 5418 | 33097 | |

| Southern Subregion (De la Plata Rive Subregion) | 846 | 3488 | 1313 | 22389 | |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 1556 | 31816 | 13429 | 27673 | |

| World Asia (2002) Africa (2002) Europe (2002) | - | 110 000 - - - | 41022 - - - | 6984 3920 5720 4230 | |

| Latin America and the Caribbean as a % of the world | - | 29 | 33 | - | |

Source: FAO, 2000, Global Water Partnership (GWP), Central America, 2006.

Planning and management of Central American water resources

To date, management of water resources in Central America has been characterized for a lack of clearly defined policies, outdated legislation or the lack thereof, overlaps of authority and functions among governing entities, supervisors and enforcers -either public or private, or external- thereby hampering management of water resources and decision-making at a political level. There has not been an integrated vision for the management of water resources, and instead, sectorial policies have prevailed (CCAD, CAC & SISCA, 2006.)

It must be acknowledged that Central American countries have implemented different initiatives aimed at harmonizing policies and legislation on water management in the region. However, these efforts have failed to bring about a change in management of water resources, and management continues to be sectorial, continues to depend on water use, and there is no differentiation between surface and underground water. None of the countries has a specific law to regulate management of underground water; instead, existing laws and policies have been established to regulate use individually. (Global Water Partnership, Central America, 2006)

Currently, Central American countries lack policies for water resources, and only Costa Rica (1942), Honduras (1927), and Panama (1966) have General Water Resources Laws, but these laws were not created with an integrated management vision. Starting in 2008, Nicaragua created the General National Water Resources Law, and since 2009 Honduras has a new Water Resources Law, shown in Annex 1.

Conceptualization and state of planning for water resources in Latin America and the Caribbean

Planning consists of defining a series of strategies to organize and direct integrated management of water resources in a logical manner. These duly documented strategies make up a plan, and are the result of an analytical decision-making and design process for these strategies and their respective activities, intended to reach predefined objectives by and for a relatively large group of players who depend on and share the same resources and territory (Dourojeanni, 2000.)

In planning for water resources, decisions must be made through legally established participative schemes so that they have validity and are accepted. Plans must be considered as management instruments at the players’ service. They must be conciliatory in economic, social and environmental terms, complementary to the objectives of each player and to the objectives of the set of players, and they must not take the place of decision-making powers. Furthermore, it is important that they are flexible enough so they may be re-adjusted every time new information is available generating changes in decisions (Dourojeanni, 2000.)

In cases where there are plans for the organization of river basins, they must be formulated taking into account higher-level regulatory frameworks, for instance, current economic policies. At the same time, plans must lead to specific regulatory frameworks which allow for their implementation. For plans to have this prerogative of a legal/regulatory nature, they must be formulated and approved in compliance with a set of procedural conditions. When regulatory frameworks are clear and stable, there is more freedom for each sector of water users of a basin to be able to draw up their individual plans. (Dourojeanni, 2000)

It is important to remember that, to the present date, almost all actions concerning water resources in countries of the region have been developed based on sectorial plans for water use, mostly aimed at prioritizing investment projects in waterworks. The need to formulate comprehensive plans and try to improve efficiency of multiple water use and of the available water systems has been ignored. Usually, powerful user sectors, such as those that use water for agricultural irrigation or to generate hydroelectric energy, have set --in many cases on their own-- the way for exploiting water in a river basin, and other sectors have more or less settled into the rhythm of the largest project. In their immense majority, ecological or social aspects have not been taken into account. Reversing this situation and way of thinking is a long-term endeavor (Dourojeanni, 2000, Guzmán, 2008.)

The case of Mexico: a good water resources planning effort

Mexico is one of the countries that has been able to make positive progress in both planning and management of water resources. Its change process began in 1996, when the National Water Commission (CONAGUA in Spanish) aimed its efforts at a more efficient and participatory management approach, and established participatory mechanisms such as the River Basin Councils and the Consultative Water Council to achieve sustainable use and exploitation of water resources with growing collaboration by local authorities at different levels and by users at a regional level, in addition to leading a process of transferring functions to local users and governments (CONAGUA, 2010.) Important results have been achieved in this process:

Integrating, refining and standardizing information related to water and its different uses

Identifying problems and alternative solutions, as well as defining strategic guidelines for water development projects

Implementing action programs and integrating long-term scenarios (2000-2025.)

Prioritizing actions every four years, and integrating a portfolio of medium- and long-term projects.

Planning process in Mexico

The planning process in Mexico started from the bottom up, i.e., it started with local perceptions, which were then integrated at the national level, and were used to define a national water policy which is centered around the National Water Program (PNH in Spanish) 2001-2006 (Valencia et al., 2004), which is based on five premises:

The country’s development should take place within a sustainable framework

Water is a strategic resource for national security

The basic unit for water management is a river basin

Management of resources should be carried out in an integrated manner

Decisions should be made with participation of users.

Integration of the planning process at a national level is reflected in a harmonization of national objectives of the water sector with the 2001-2006 National Development Plan (PND in Spanish), where these objectives turn into decision-making factors for achieving overall objectives.

One of the most important achievements in the water planning process was the integration of each of the 13 Hydrological Administrative Regions of the 2002-2006 Regional Water Programs. Objectives and goals to be achieved are presented at a regional level, as well as the most important strategies and actions related to water use and exploitation that should be implemented to contribute to solving existing problems in each region, in keeping with the PNH.

The water planning process has been characterized by a high level of participation of organized society through the River Basin Councils, with 2700 meetings carried out between 1998 and 2003. The River Basin Councils validated the information produced by the 2002-2006 Regional Water Programs, which is considered to be the governing document regarding regional water planning.

Integrated Water Resources Management (GIRH in Spanish)

During the last few years, Mexico’s water sector has evolved towards an integrated water management approach, based on changes in the legal framework and the administrative agency at a federal level, as well as on an orderly, participatory planning process with users (Valencia et al., 2004.)

The fundamental pillars that support Integrated Management of Water Resources (GIRH) are:

The National Water Law, enacted in 1992 and amended in April, 2004.

Creation of the National Water Commission as a Federation’s superior body of a technical, regulatory and consultative nature in matters relating to GIRH, including management, regulation, control, and protection of the public domain over water.

When the Legislative Branch set forth the National Water Law (LAN), the concept of GIRH gained strength in the public agenda, assisted by an acknowledgement that river basins are the basis for the National Water Policy. This in turn strengthened the mechanisms to maintain and reestablish hydrological balance of the country’s river basins and vital eco-systems for water. Specifically, the LAN defines GIRH as the process for promoting coordinated management and development of water resources, land, the resources related to them, and the environment. The aim is to maximize social and economic well-being equitably, without endangering sustainability of vital ecosystems.

Studies have been carried out in all regions of Mexico analyzing the resources of river basins in an integrated fashion, including their hydric balance and water demand, and their problems as a whole. Additionally, necessary strategies are designed to reduce impacts and promote sustainable development of river basins. These studies have provided enough elements to lead to economic and social development of river basins through sustainable management of their natural resources.

Involvement of society in the process has allowed players to be informed about -and participate in- designing strategies to solve problems and promote improvements in river basin zones, leading institutions of the three branches of Government to work jointly to achieve social, economic and environmental development of these zones.

CONAGUA has envisioned GIRH at river basin level as a process in which the following aspects must be considered:

Integrated use of water

Interaction between surface and underground water

Water availability - quantity and quality

Relations between water and other natural resources of river basins

Natural resources and their relationships with economic and social development.

Another important aspect arising from GIRH is that public policies are cross-sectorial. This means that efforts are jointly undertaken by various organizations from the Federal, State and Municipal Public Administrations to address the problems faced by a given zone, with the great advantage that efforts to solve certain problems contribute to some extent to the solution of yet other problems.

To promote GIRH implementation, the CONAGUA re-examined its representativeness in the area of river basins, hydrological regions and administrative-hydrological regions, and is giving way to River Basin Organizations. These are specialized autonomous technical, administrative and juridical units, and must work jointly with River Basin Councils to achieve GIRH in river basins and hydrological regions.

Conclusions

The state of water resources in Latin America and the Caribbean

Even though Latin America and the Caribbean have abundant water resources, accounting for over 30% of the world’s water availability, they are distributed quite unevenly. A great part of them are in the Amazon subregion (Peru, Colombia, and Brazil) - countries that are not densely populated. On the other hand, in arid and semi-arid zones such as North and Central Mexico, where a large part of the population lives, and which are the engine of the country’s economic activity, water is constantly scarce in terms of both quantity and quality.

Integral planning and management of water resources

A great variety of institutional and legal approaches are implemented for water management in Latin American and Caribbean countries. While some countries are preparing revised versions of bills for new water laws, others are trying to amend already approved laws, and others are in the process of establishing their regulations and enforcement mechanisms.

The practical situation in all countries involves an administrative structure for the water sector which is complex, and restricts the achievement of integrated planning and management. In all cases, the actual capacity of the State to regulate use of water resources and enforce regulations is quite weak, and is further weakened due to a generalized lack of synchronization and to institutional sectorization. In many cases, administrative systems are fragmented, present important management gaps, and are vulnerable to politization of technical activities.

On the positive side, there are important experiences and efforts such as those in Mexico, Chile, and Brazil. The rest of the countries analyzed have intended to introduce reforms in multiple occasions, but have not yet been able to adjust the regulatory framework of the water sector -in fact, in some countries there are no regulations, and in most others they are obsolete (Ballestero et al., 2005)- vis-à-vis the current nature of water use and exploitation problems, and society’s current concepts and practices.

Many difficulties have to be faced when seeking broad social consensus about reforms to water regimes. When this issue is addressed, some criteria are considered to be less important than others, although the criteria used do not necessarily correspond to the nature of the issue under discussion. Relevant interests may be excluded from the reform process, for instance, small groups may have a disproportionate influence, or the goal pursued may have more to do with circumstantial problems affecting user sectors, than with seeking an integrated water management approach.

The common element in the issue of water resources management in Latin America and the Caribbean is a growing awareness of the need to promote integrated planning and management.

In the case of Mexico, although progress has been achieved in various phases of water management, the water sector is currently confronting a new challenge: Integrated Management of Water Resources. Obviously, in this case the practical use of the concept does not start from zero -there are structures, mechanisms and agreements that have been strengthened through the water planning process which started in 1996. An outstanding effort is the consolidation of social participation through the River Basin Councils, reflected in the approval and validation of the 2002-2006 Regional Water Programs as an overarching document for water policy in Hydrological-Administrative Regions. The provisions in amendments to the National Water Law indicate that the national water policy is based on integrated management of water resources by river basins in a decentralized and integrated manner, where direct actions and decisions from local sectors must take priority.

The state, planning and management of water resources in Central America

In spite of efforts undertaken by governments and Central American civil society to move towards implementation of the set of principles and concepts that are part of the new water management approach, the expected progress is not being achieved, due to characteristics of the economic, social and institutional contexts in this sphere in almost all countries. In brief, the state of water resources in Central America is characterized by many deficiencies related to political, economic and institutional instruments.

Recommendations

Given the importance of water resources for sustainable development, a country-level planning model must have at least the following elements (Van Hofwegen & Jaspers, 2000):

Understand water resources as a geographically defined system, consisting of both surface and underground water, along with all their physical, chemical and biological characteristics.

The geographic area associated with a major source of water must be delimited based on functional consistency between hydrological, morphological and ecological aspects.

The importance of use of water resources must be taken into account in their development and management. If such use is taken into account correctly during the planning and management process for water resources, society’s water use requirements will be considered when planning technical and legislative interventions for the functioning of water systems.

The legal framework must necessarily be clear, up-to-date, and consider future needs.

There must be a directing and auditing body for water resources that is capable of leading the efforts of participating institutions.

Given Latin American reality in general, and that of Central American countries in particular - as presented in the previous discussion- it is advisable to design a comprehensive water policy including economic, social, anthropological, legal, and technical aspects. This should determine the organization of water use aimed at economic and social development in terms of efficiency and equity.

Such water policy must have a common foundation between countries so that there is consistency at a regional level, mostly in cases where there are trans-border river basins. This foundation must be based on the concepts and principles contained in different international documents aimed at integrated water management, such as the Dublin Principles.

The interests of water resources themselves should be taken into account when designing such a policy -i.e., the possibility of protecting and improving water quantity and quality. In addition, it must be based on the broad participation of all population sectors, thereby taking into account the interests of poor urban and rural segments, among others, at the local level, and ensure their access to water, as indicated by ECLAC (2005.)

In keeping with this line of thinking, the next step would be designing and implementing an administration system for water rights based on planning of water resources, which should begin with acknowledging the actual situation at the local level.

It is imperative to know and generate information about water supply and demand by sectors, at least at the level of national river basins, using monthly water balances and scenarios of high, medium, and low demand projected over at least 25 years. Without such information, water planning and managing is virtually impossible. It is equally necessary to provide an estimation of environmental water demand in these studies, for example environmental flows and water flows to wetlands.

Finally, the water management approach should be oriented around management of river basins. This necessarily leads to the development of adequate institutions, a topic that has started to be discussed in Central American countries. This discussion should provide mechanisms for conflict resolution. This is necessary not only because of the approach itself, but also because conflicts among water users have begun to be more frequent and critical.